Abstract

Background

Klebsiella species are among the most common causes of bloodstream infection (BSI). However, few studies have evaluated their epidemiology in non-selected populations. The objective was to define the incidence of, risk factors for, and outcomes from Klebsiella species BSI among residents of the western interior of British Columbia, Canada.

Methods

Population-based surveillance was conducted between April 1, 2010 and March 31, 2017.

Results

151 episodes were identified for an incidence of 12.1 per 100,000 population per year; the incidences of K. pneumoniae and K. oxytoca were 9.1 and 2.9 per 100,000 per year, respectively. Overall 24 (16%) were hospital-onset, 90 (60%) were healthcare-associated, and 37 (25%) were community-associated. The median patient age was 71.4 (interquartile range, 58.8–80.9) years and 88 (58%) cases were males. Episodes were uncommon among patients aged < 40 years old and no cases were observed among those aged < 10 years. A number of co-morbid medical illnesses were identified as significant risks and included (incidence rate ratio; 95% confidence interval) cerebrovascular accident (5.9; 3.3–9.9), renal disease 4.3; 2.5–7.0), cancer (3.8; 2.6–5.5), congestive heart failure (3.5; 1.6–6.6), dementia (2.9; 1.5–5.2), diabetes mellitus (2.6; 1.7–3.9), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (2.3; 1.5–3.5). Of the 141 (93%) patients admitted to hospital, the median hospital length stay was 8 days (interquartile range, 4–17). The in-hospital and 30-day all cause case-fatality rates were 24/141 (17%) and 27/151 (18%), respectively.

Conclusions

Klebsiella species BSI is associated with a significant burden of illness particularly among those with chronic co-morbid illnesses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The Klebsiella genus, which including the species K. pneumoniae, (including subspecies pneumoniae and ozonae), K. oxytoca, and K. variicola are important human pathogens. Klebsiella pneumoniae is second to Escherichia coli as the most frequent cause of Gram-negative bloodstream infections (BSI) in both hospital and community settings [1]. Klebsiella pneumoniae is an important cause of pneumonia, urinary tract infections, septicemia, and intra-abdominal infections [2, 3]. Klebsiella pneumoniae has become increasingly important in recent years, as invasive hypermucoid strains have been linked to pyogenic liver abscesses most notably in Taiwan and Korea [4, 5], and there has been an upswing in extended spectrum-β-lactamase (ESBL) producing strains worldwide [6,7,8]. Species other than K. pneumoniae are overall less frequent and have been associated with conditions including BSIs, urinary tract infections, soft tissue infections, and respiratory tract infections [9,10,11].

Population-based studies minimize a number of important biases and have been recognized as optimal designs to evaluate the epidemiology of BSIs [12]. However, to our knowledge only three previous studies have evaluated Klebsiella species BSI in non-selected populations [1, 13, 14]. Furthermore, only one of these has quantified the risks for development of Klebsiella species BSI related to specific co-morbid illnesses [1]. The objective of this study was to determine the incidence and risk factors for acquiring Klebsiella species BSI among residents of a non-selected Canadian population.

Methods

Study population & surveillance

Population surveillance was conducted in the western interior region of British Columbia, Canada (2016 population 182,422) as previously described [15]. The regional microbiology laboratory at the Royal Inland Hospital in Kamloops identified all residents in the selected area with Klebsiella species BSI. A senior infectious disease consultant (KBL) then performed a case-by-case chart review to abstract clinical information. The Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) was used to classify comorbid illnesses [16]. This study was granted a waiver of individual informed consent by the Interior Health Research Ethics Board (file 201,314,052-I).

Laboratory procedures and definitions

The BacT/Alert 3D System (bioMerieux, France) was used for blood culturing. Draw of two sets of blood cultures consisting of aerobic/anaerobic bottle pairs from different sites was standard. Organisms were isolated and speciated by examining lactose-fermenting mucoid colonies on MacConkey agar plates. Oxidase tests and MALDI-TOF were then used, along with Gram stain results, for species identification. For the purposes of this study, K. pneumoniae included those identified as K. pneumoniae and K. pneumoniae subspecies pneumoniae or ozonae.

Incident Klebsiella species BSI was established by the first growth from one or more blood culture sets. Repeat positive cultures within 30 days were deemed be of the same episode. Those reoccurring within 30–365 days were classified as incident if the index episode resolved following treatment. Contaminants were excluded and clinical significance and determinants were established by a review of all information in the electronic health record. Hospital-onset BSI were those where the incident blood culture was drawn 48 h or more and community-onset BSI less than 48 h after acute care hospital admission [17]. Community-onset BSIs were sub-classified as either community- or healthcare-associated using the Freidman et al definitions [18].

Statistical analysis

Stata version 15 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX) was used for all analyses. Fisher’s exact test was used to examine differences in proportions among categorical data. Skewed continuously distributed variables were described using medians with inter-quartile range (IQR) and were compared using the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test. Incidence rates were expressed as annual rates per 100,000 resident population and calculated using census data [19]. Risks were reported as incidence rate ratios (IRR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) and were calculated using as numerator and denominator the incidence with and without a factor, respectively. Selected co-morbid illnesses were assessed as risk factors for the development of Klebsiella species BSI. Denominator data was obtained from local sources [20, 21], provincial and national surveys [22,23,24,25,26,27,28], and studies published elsewhere [29]. P-values less than 0.05 were deemed to represent statistical significance.

Results

Incidence

During the seven years of surveillance, 153 incident BSI isolates of Klebsiella species were identified. In two cases infections had two different incident Klebsiella species concomitantly isolated and these included one patient with K. oxytoca and K. pneumoniae while another with K. oxytoca and K. variicola co-infection. There were therefore 151 incident Klebsiella species BSI episodes among 139 regional residents for an overall annual incidence rate of 12.1 per 100,000 population per year. The incidence of K. pneumoniae and K. oxytoca were 9.1 and 2.9 per 100,000 population per year, respectively. The remaining two incident isolates were K. variicola. Eleven patients had a second and one patient had a third episode of Klebsiella species BSI during the surveillance period. Twenty-four cases (16%) were hospital-onset, 90 (60%) were healthcare associated, and 37 (25%) were community-associated.

The annual incidence varied during the study years as shown in Fig. 1. The first five years of the study demonstrated moderate year-to-year variability ranging from 6.8 to 11.7 per 100,000 annually but there was then a marked increase during the fifth and six years of the study (Fig. 1). Although both species increased in incidence in the latter years of the study this was predominantly related to K. pneumoniae BSI in the last study year.

Risk factors and predisposing conditions

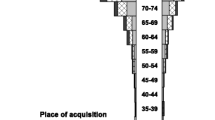

The median patient age was 71.4 (IQR, 58.8–80.9) years and 88 (58%) were males. No cases were observed among those aged less than 10 years and the incidence increased with older age as shown in Fig. 2. Males were at higher risk but this was not statistically significant (14.0 vs. 10.1 per 100,000; IRR, 1.4; 95% CI, 1.0–1.9; p = 0.06).

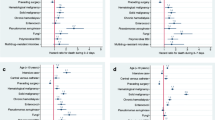

The median CCI was 2 (IQR, 1–4). Twenty-eight (19%) patients had a CCI of zero, and sixty-two (41%) had scores of 1–2, thirty-two (21%) 3–4, and twenty-nine (19%) had five or more. A number of co-morbidities were examined as risks for development of a Klebsiella species BSI within the population and these are shown in Table 1.

Clinical foci and microbiology

The most common focus of infection was intra-abdominal or genitourinary as shown in Table 2. Although K. pneumoniae was much more likely to be of hospital-onset as compared with K. oxytoca BSI (23/113; 20% vs. 1/35; 3%; relative risk 7.1; 95% confidence interval 1.0–50.9; p = 0.016), otherwise the demographics and clinical features were similar (Table 2). Although there was a high rate of resistance to ampicillin, most isolates overall were susceptible to ceftriaxone, ciprofloxacin, gentamicin, and co-trimoxazole (Table 2). As compared to K. pneumoniae, K. oxytoca had a significantly reduced rate of susceptibility to cefazolin (Table 2).

Hospital admission and outcome

One hundred and forty-one (93%) patients were admitted to hospital for a median hospital length stay of 8 (IQR, 4–17) days. The in-hospital and 30-day all cause case-fatality rates were 24/141 (17%) and 27/151 (18%), respectively. The 30-day all cause case-fatality rates were 20% (23/113) and 9% (3/35; p = 0.1) for K. pneumoniae and K. oxytoca, respectively.

Discussion

In this study, we observed that Klebsiella species are frequent causes of BSI. The incidence rate of Klebsiella species BSI was 12.0/100,000, and a number of co-morbid medical conditions were associated with significantly increased risk. Furthermore, one in five patients suffering from Klebsiella species BSI died within 30 days of diagnosis. Klebsiella species BSI cause a significant burden of illness in our population.

To our knowledge, there are only three previous population-based studies published for comparison [1, 13, 14]. Meatherall et al reported on 640 episodes in the Calgary area of Canada during the years 2000 to 2007 and found an incidence rate of for K. pneumoniae of 7.1/100,000 [1]. Pepin reported an incidence of 18.7/100,000 in Sherbrooke, Canada, between the years 1997 and 2007, with 411 episodes identified in that time [14]. Finally, Al-Hasan reported 127 episodes in Olmsted County, Minnesota, between the years 1998 and 2007, with an annual incidence rate of 11.7/100,000 for Klebsiella species BSI, and 9.7/100,000 for K. pneumoniae specifically [13]. The cumulative data from North American population-based studies to date indicate that the incidence rate for Klebsiella species BSI is comparable to our observed rate of 12 per 100,000. Individual differences between studies may potentially be explained in part by differences in demographics, rates of culturing, and distribution of risk factors in these populations.

A number of studies have identified co-morbidities most notably cancer and diabetes as risk factors for development of Klebsiella species BSI [1, 14, 30,31,32,33,34]. However, with the exception of the population-based investigation reported by Meatherall et al, these studies have been within selected cohorts that are at significant potential risk for bias. In their study from Calgary, Meatherall et al found a number of determinants and that solid organ transplantation, chronic liver disease, dialysis, and cancer were the most important risk factors for development of K. pneumoniae BSI [1]. We also observed that renal disease and cancer were significant risk factors for Klebsiella species BSI but notably we did not find that liver disease significantly increased the risk. While diabetes was found to be a significant risk factor in both of our studies, after considering the high prevalence among controls in the population the magnitude of this risk was relatively low compared to other co-morbidities (Table 2). There are many reasons why observed risk factors may be different in populations and may be related to the specific populations under evaluation and the differences in study methodologies and definitions.

While this study benefits from the population-based design there are some limitations that merit discussion. First, it is possible that we could have failed to ascertain cases that occurred among residents of our region seeking health care outside our region. Given that almost all tertiary services are available in our area, we suspect that this represents a small number but do not have actual empiric data to justify this claim. Second, a diagnosis of a BSI requires a positive blood culture and as such is related to the decision of clinicians to draw a specimen for testing. This is a limitation inherent to all BSI studies. Third, in establishing comorbid illnesses we did not have individual patient level data on co-morbid illnesses on residents of the region that did not develop BSI and therefore had to estimate prevalence rates in our calculations. A degree of imprecision therefore exists in our determinations and the magnitude of the risk factors reported should be interpreted accordingly. Finally, because of the lack of individual co-morbidity data on controls we were not able to determine independent risk factors for acquisition using multivariable statistics.

Conclusion

In summary, our study documents the major burden of Klebsiella species BSI in our region and is a significant addition to the small number of previous population-based studies conducted in other areas in Canada and the United States. We further identify and confirm that a number of co-morbidities are risk factors for these infections. Further population-based studies conducted in other regions outside of North America are warranted.

Availability of data and materials

Ethics board approval agreement precludes public sharing of data from this study. Datasets may be made available on reasonable request by contacting the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- BSI:

-

Bloodstream Infection

- CCI:

-

Charlson Comorbidity Index

- CHF:

-

Congestive heart failure

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- COPD:

-

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- CVA:

-

Cerebrovascular accident

- ESBL:

-

Extended Spectrum-Beta-Lactamase

- IQR:

-

Inter-Quartile Range

- IRR:

-

Incidence-Rate Ratio

- MALDI-TOF:

-

Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization – Time Of Flight

- MI:

-

Myocardial Infarction

- PVD:

-

Peripheral vascular disease

- RIH:

-

Royal Inland Hospital

References

Meatherall BL, Gregson D, Ross T, Pitout JD, Laupland KB. Incidence, risk factors, and outcomes of Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia. Am J Med. 2009;122(9):866–73.

Gupta A. Hospital-acquired infections in the neonatal intensive care unit--Klebsiella pneumoniae. Sem Perinatol. 2002;26(5):340–5.

Podschun R, Ullmann U. Klebsiella spp. as nosocomial pathogens: epidemiology, taxonomy, typing methods, and pathogenicity factors. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11(4):589–603.

Tsay RW, Siu LK, Fung CP, Chang FY. Characteristics of bacteremia between community-acquired and nosocomial Klebsiella pneumoniae infection: risk factor for mortality and the impact of capsular serotypes as a herald for community-acquired infection. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(9):1021–7.

Kang CI, Kim SH, Bang JW, Kim HB, Kim NJ, Kim EC, Oh MD, Choe KW. Community-acquired versus nosocomial Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia: clinical features, treatment outcomes, and clinical implication of antimicrobial resistance. J Korean Med Sci. 2006;21(5):816–22.

Tawfik AF, Alswailem AM, Shibl AM, Al-Agamy MH. Prevalence and genetic characteristics of TEM, SHV, and CTX-M in clinical Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from Saudi Arabia. Microb Drug Resist. 2011;17(3):383–8.

Feizabadi MM, Delfani S, Raji N, Majnooni A, Aligholi M, Shahcheraghi F, Parvin M, Yadegarinia D. Distribution of Bla (TEM), Bla (SHV), Bla (CTX-M) genes among clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae at Labbafinejad hospital, Tehran. Iran Microb Drug Resist. 2010;16(1):49–53.

Paterson DL, Hujer KM, Hujer AM, Yeiser B, Bonomo MD, Rice LB, Bonomo RA. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in Klebsiella pneumoniae bloodstream isolates from seven countries: dominance and widespread prevalence of SHV- and CTX-M-type beta-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47(11):3554–60.

Rodriguez-Medina N, Barrios-Camacho H, Duran-Bedolla J, Garza-Ramos U. Klebsiella variicola: an emerging pathogen in humans. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2019;8(1):973–88.

Nagamura T, Tanaka Y, Terayama T, Higashiyama D, Seno S, Isoi N, Katsurada Y, Matsubara A, Yoshimura Y, Sekine Y, et al. Fulminant pseudomembranous enterocolitis caused by Klebsiella oxytoca: an autopsy case report. Acute Med Surg. 2019;6(1):78–82.

Goldstein EJ, Lewis RP, Martin WJ, Edelstein PH. Infections caused by Klebsiella ozaenae: a changing disease spectrum. J Clin Microbiol. 1978;8(4):413–8.

Laupland KB. Defining the epidemiology of bloodstream infections: the 'gold standard' of population-based assessment. Epidemiol Infect. 2013;141(10):2149–57.

Al-Hasan MN, Lahr BD, Eckel-Passow JE, Baddour LM. Epidemiology and outcome of Klebsiella species bloodstream infection: a population-based study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(2):139–44.

Pepin J, Yared N, Alarie I, Lanthier L, Vanasse A, Tessier P, Deveau J, Chagnon MN, Comeau R, Cotton P, et al. Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteraemia in a region of Canada. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16(2):141–6.

Laupland KB, Pasquill K, Parfitt EC, Naidu P, Steele L. Burden of community-onset bloodstream infections, Western interior, British Columbia. Canada Epidemiol Infect. 2016;144(11):2440–6.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chron Dis. 1987;40(5):373–83.

Morin CA, Hadler JL. Population-based incidence and characteristics of community-onset Staphylococcus aureus infections with bacteremia in 4 metropolitan Connecticut areas, 1998. J Infect Dis. 2001;184(8):1029–34.

Friedman ND, Kaye KS, Stout JE, McGarry SA, Trivette SL, Briggs JP, Lamm W, Clark C, MacFarquhar J, Walton AL, et al. Health care--associated bloodstream infections in adults: a reason to change the accepted definition of community-acquired infections. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(10):791–7.

Kroger E, Tourigny A, Morin D, Cote L, Kergoat MJ, Lebel P, Robichaud L, Imbeault S, Proulx S, Benounissa Z. Selecting process quality indicators for the integrated care of vulnerable older adults affected by cognitive impairment or dementia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:195.

Population/Local Health Areas &Facility Profiles. Available at: https://www.interiorhealth.ca/AboutUs/QuickFacts/PopulationLocalAreaProfiles/Pages/default.aspxv accessed April 22, 2019.

HIV Monitoring Quartley Report: Interior Health. Available at: http://stophivaids.ca/qmr/2018-Q4/#/iha 2Accessed April 22, 2019.

Ellison LF, Wilkins K. Canadian trends in cancer prevalence. Health Rep. 2012;23(1):7–16.

Prevalence of Chronic Diseases Among Canadian Adults, Public Health Agency of Canada. Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/chronic-diseases/prevalence-canadian-adults-infographic-2019.html Accessed April 22, 2019. .

Heart Disease in BC, Cardiac Services BC. Available at: http://www.cardiacbc.ca/health-info/heart-disease-in-bc Accessed April 22, 2019.

Stroke in Canada: Highlights from the Canadian Chronic Disease Surveillance System, Public Health Agency of Canada. Available at https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/stroke-canada-fact-sheet.html Accessed April 22, 2019.

Arora P, Vasa P, Brenner D, Iglar K, McFarlane P, Morrison H, Badawi A. Prevalence estimates of chronic kidney disease in Canada: results of a nationally representative survey. CMAJ. 2013;185(9):E417–23.

Liver Disease in Canada, Canadian Liver Foundation Available at: https://www.liver.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Liver-Disease-in-Canada-E-3.pdf Accessed April 23, 2019.

Lovell M, Harris K, Forbes T, Twillman G, Abramson B, Criqui MH, Schroeder P, Mohler ER 3rd, Hirsch AT. Peripheral arterial disease C: peripheral arterial disease: lack of awareness in Canada. Can J Cardiol. 2009;25(1):39–45.

Wong, R., Davis, A. M., Badley, E., Grewal, R., Mohammed, M: Prevalence of Arthritis and Rhematic Diseases Around the World, 2010. MOCA. Available at: http://www.modelsofcare.ca/pdf/10-02.pdf Accessed April 22, 2019.

James R, Hijaz A. Lower urinary tract symptoms in women with diabetes mellitus: a current review. Curr Urol Rep. 2014;15(10):440.

Huang CH, Tsai JS, Chen IW, Hsu BR, Huang MJ, Huang YY. Risk factors for in-hospital mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes complicated by community-acquired Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia. J Formos Med Assoc. 2015;114(10):916–22.

Zhang Y, Zhao C, Wang Q, Wang X, Chen H, Li H, Zhang F, Li S, Wang R, Wang H. High prevalence of Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae infection in China: geographic distribution, clinical characteristics, and antimicrobial resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60(10):6115–20.

Li J, Ren J, Wang W, Wang G, Gu G, Wu X, Wang Y, Huang M. Risk factors and clinical outcomes of hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae induced bloodstream infections. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2018;37(4):679–89.

Sanchez-Lopez J, Garcia-Caballero A, Navarro-San Francisco C, Quereda C, Ruiz-Garbajosa P, Navas E, Dronda F, Morosini MI, Canton R, Diez-Aguilar M. Hypermucoviscous Klebsiella pneumoniae: a challenge in community acquired infection. IDCases. 2019;17:e00547.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was conducted without external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CBR contributed to data collection, analysis, and drafting of the manuscript. LS, KP, and ECP contributed to data collection. KBL contributed to data collection, analysis, and manuscript drafting. All authors contributed to manuscript revision and approval of the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Interior Health Research Ethics Board approved this study and granted a waiver of individual informed consent (file 201314052-I).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Reid, C.B., Steele, L., Pasquill, K. et al. Occurrence and determinants of Klebsiella species bloodstream infection in the western interior of British Columbia, Canada. BMC Infect Dis 19, 1070 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-4706-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-4706-8