Abstract

Background

In meta-analyses of genetic association studies, ancestry and ethnicity are not accurately investigated. Ethnicity is usually classified using conventional race/ethnic categories or continental groupings even though they could introduce bias increasing heterogeneity between and within studies; thus decreasing the external validity of the results. In this study, we performed a meta-analysis using a novel ethnic classification system to test the association between MCP-1 -2518 polymorphism and pulmonary tuberculosis. Our new classification considers genetic distance, migration and linguistic origins, which will increase homogeneity within ethnic groups.

Methods

We included thirteen studies from three continents (Asia, Africa and Latin America) and considered seven ethnic groups (West Africa, South Africa, Saharan Africa, East Asia, South Asia, Persia and Latin America).

Results

The results were compared to the continental group classification. We found a significant association between MCP-1 -2518 polymorphism and TB susceptibility only in the East Asian and Latin American groups (OR 3.47, P = 0.08; OR 2.73, P = 0.02). This association is not observed in other ethnic groups that are usually considered in the Asian group, such as India and Persia, or in the African group.

Conclusions

There is an association between MCP-1 -2518 polymorphism and TB susceptibility only in the East Asian and Latin American groups. We suggest the use of our new ethnic classification in future meta-analysis of genetic association studies when ancestry markers are not available. This new classification increases homogeneity for certain ethnic groups compared to the continental classification. We recommend considering previous data about migration, linguistics and genetic distance when classifying ethnicity in further studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Tuberculosis disease (TB) is a major public health problem worldwide. To create new strategies that will improve TB control, we need a better understanding of the biological, environmental, social, and ethnic factors [1]. One promising route is the study of polymorphisms involved in pulmonary TB susceptibility [2, 3]. Several human genes have been associated with TB development [4–6], including the monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1), also called CCL2. MCP-1 belongs to a group of CC chemokines located in chromosome 17q11.2. MCP-1 protein interacts with chemokine C-C motif receptor 2 (CCR2) to activate and recruit monocytes, macrophages, CD4+ T cells and immature dendritic cells to the site of infection [7–9]. The presence of MCP-1 protein in an adequate concentration is important for granuloma formation and M. tuberculosis clearance [10, 11].

Although there are more than ten genetic polymorphisms in the MCP-1 promoter and coding region, only the MCP-1 -2518 A/G allele (reference sequence 1024611) is functional and affects gene expression [10]. A substitution from A to G in -2518 position of the promoter region increases the levels of MCP-1. This action decreases the concentration of IL-12p40, which recruits and activates memory/effector Th1 cells, thus impairing long-term protection to intracellular pathogens [10]. Observational studies have shown that MCP-1 -2518 A/G polymorphism is associated with the development of pulmonary tuberculosis (pTB) and could be a potential marker for latent TB and disease severity [3, 12]. However, this association is different among countries such as Persia, India, Korea and China, which share continental groups [13, 14].

Geographical distribution by continents is the conventional way to assess ethnicity in meta-analysis of genetic association studies. However, population genetics has demonstrated that ethnic composition is related more with genetic distance, migration and linguistic origins rather than continental groups. In terms of ancestry biomarkers, continental grouping relies on markers such as Y-DNA and mtDNA haplogroups and varies within continents [15, 16]. As a consequence, conventional classification might introduce bias and increase heterogeneity between and within studies, decreasing the external validity of the results. Thus, it is questionable if the conventional classification is an appropriate proxy for ethnicity.

In order to have a better understanding of the relationship between ethnicity and the susceptibility to infectious diseases such as TB, we evaluated the association between the MCP-1 -2518 A/G polymorphism and pTB susceptibility using a new multi-factorial ethnic classification and compared it with the conventional approach of continental groups. This new classification is based on previous research on genetic distance, migration and linguistic origins [16–19], which improves the homogeneity of ethnic groups. We believe that our new classification for ethnicity offers a more robust approach to explain susceptibility to disease, and that it can increase the internal validity of genetic studies when ancestry markers are not available.

Methods

Search strategy

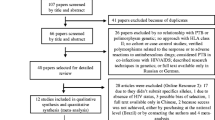

A literature search was carried out in NCBI database, Scielo and Lilacs to identify genetic association studies between MCP-1 polymorphism and pTB risk prior to December 2013. We used the following MESH terms: (("Polymorphism, Genetic"[Mesh]) AND "Chemokine CCL2"[Mesh]) AND "Tuberculosis"[Mesh]. Mesh term “MCP-1” gave the result CCL2. “Reference sequence 1024611 A/G” gave zero results. Our selection criteria included: 1) studies evaluating the association between MCP-1-2518 A/G and TB risk, 2) observational studies, 3) pulmonary TB, 4) studies performed in adults and children, 4) patients without HIV or cancer, 5) available allelic and the genotype frequencies to estimate an odds ratio (OR), 6) control groups that met Hardy Weinberg Equilibrium, and 7) articles published until December 2013. Studies that did not meet these criteria were excluded. When original articles included more than one study population, we considered each as an independent study. In case of multiple publications on the same study, we included the study with the larger sample and/or the most recently published. The data search retrieved 23 articles. Ten studies were excluded because they were reviews or meta-analyses, or corresponded to pediatric populations, spinal TB, latent TB, HIV positive individuals or data from controls was inaccessible. At the end, 13 studies (7651 cases and 8056 controls) [3, 10, 20–30] (Fig. 1) were considered.

Data collection

All articles were separately extracted, reviewed and collated by two independent reviewers who checked for any discordance and reached a consensus in all items. Authors were contacted by email when we needed more information about an article. The following information was extracted for each study: author, year of publication, country of origin, ethnicity, sample size, type of study population, TB definition, allele and the genotype frequencies in cases, controls and methods. The information was systematically reviewed using STROBE and STREGA parameters [31, 32].

Ethnic classification

We proposed a new ethnic classification based on previous information about genetic distance, migration and linguistic origins [16, 17, 33–35] and compared it to the conventional classification. The new ethnic classification considered previous findings about genetic distance [17]. For this purpose, data such as country of origin was extracted from each study. Finally our new ethnic classification included: Middle East Asia (Persia), East Asia (Korea and China), South Asia (India), Saharan region (Morocco and Tunisia), South Africa (South Africa), West Africa (Guinea-Bissau, Gambia, and Ghana) and Latin America (Peru and Mexico). The conventional classification includes three groups: Africa (37 %), Asia (43.8 %) and Latin America (18.8 %). The characteristics of each study are listed in Table 1. We hypothesized that the new classification creates ethnic groups that have more homogeneity than the groups obtained by the conventional group classification.

Statistical analysis

For each study, the Hardy Weinberg Equilibrium (HWE) was calculated for the controls using X 2 statistic. Genotypes deviated from HWE if two-sided p values were <0.05. Begg funnel plot and Egger’s test indicated publication bias if p value was <0.05. Sensitivity analysis was performed by removing one study at a time to assess the stability of the meta-analysis results.

To prove our hypothesis, we assessed heterogeneity and the magnitude of association for each ethnic group. We assessed heterogeneity by using the χ 2 based Q test and I 2 statistic. P values less than 0.01 were considered significant for heterogeneity. To assess the magnitude of association (pooled OR), in the presence of homogeneity, we used a fixed effects model (inverse variance weighted). Otherwise, we used a random effects model (DerSimonian and Laird, D + L). Pooled OR for the association between MCP-1 - 2518 A/G polymorphism and pTB risk was determined in three steps. First, we did an allelic comparison (G vs. A) to determine the pooled OR in the overall data and by ethnic subgroups. Second, using our new ethnic classification, we analyzed four genotype models: a) recessive (GG vs. AG + AA), b) homogenous co-dominant (GG vs. AA), c) heterogeneous co-dominant GA vs. AA) and c) dominant (GG + GA vs. AA). Third, we compared these results to those obtained from the analysis using the conventional classification. Odds ratio estimates were considered significant if P was <0.05, and were expressed using a 95 % confidence interval (CI). When analyzing by ethnicity, we used the groups that had ≥1 degree of freedom. For our analysis, the wild type allele was A, and the risk allele was G. We did not adjust our model for environmental effects. The statistical analysis was performed using STATA 11.0. (STATA Corp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

The conventional ethnic analysis found heterogeneity in the three continental study groups for both allelic and genotype analysis. Using our new classification, we found homogeneity for South Asia (India) and West Africa, which were further analyzed with a fixed effects model. We could not improve homogeneity within the rest of the ethnic groups and used a random effects model for their analysis. According to the Begg’s funnel plot and Egger’s test, we did not find any bias in the analysis of the entire group (t = 1.76, P = 0.1; Fig. 2). Sensitivity analysis did not find any prominent effect of each individual study when estimating the pooled OR. Characteristics of each study, allele and genotype distributions are shown in Tables 1 and 2 respectively.

G allele frequencies in conventional and new ethnic classification

The conventional classification showed that G allele is frequent in Asia and South America (45 % in cases vs. 39 % in controls and 70 % in cases vs. 59 % in controls, respectively) but not in Africa (22 % in cases vs. 20 % in controls). Our new ethnic classification showed that East Asia has the highest frequency of the G allele (57 % cases and 46 % controls) in the Asian group. In Latin America, this allele has a similar frequency in Mexico and Peru. In contrast, the African ethnic groups (Saharan, South and West Africa) have a low frequency of G allele in a similar proportion (Fig. 3). The pooled OR shows that presence of G allele increases the risk to develop pTB by 30 %. The conventional classification shows that this association is only significant for South America and Asia (OR 1.76, 95 % CI 1.7-2.6, P < 0.01; OR = 1.41,95 % CI 1.02-1.96, P = 0.03, respectively). Interestingly, our new ethnic classification showed that in the Asian continent, the G allele increases risk only in the East Asian ethnic group (OR 1.9, 95 % CI 1.2-3, P <0.01), but not for South Asian and Persia (Fig. 4). We did not find any association for any of the African groups.

G allele MCP-1 -2518 polymorphism distribution in study populations and incidence of pulmonary TB (2010). a shows the frequency of G allele among ethnic countries. G allele is more frequent in individuals with pulmonary TB from East Asian and Latin American ethnic countries (* = P <0.01) and there is no difference within African subgroups, Persia and South Asia. b shows the ethnic countries considered in our new ethnic classification. c The chart shows the incidence of tuberculosis in the groups studied found at http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.TBS.INCD. (this incidence includes HIV cases)

New and traditional ethnic classification to assess TB susceptibility in MCP-1 -2518 G allele carriers. We observe that the new classification finds a significant association only for the East Asian and Latin American groups. In South Asia (India), where there is homogeneity between studies, we can rule out that the polymorphism is associated with pulmonary TB

MCP-1 -2518 A/G genotypes and pTB susceptibility

The conventional classification showed that individuals from South America and Asia that carry GG genotype have 2.7 and 2.1 times the risk to develop pTB as compared to the ones with AA genotype (OR 2.72, 95 % CI 1.6–6.3, P = 0.02 and OR 2.09, 95 % CI 1.1–3.8, P = 0.01, respectively). The recessive model also showed increased susceptibility in both continents but to a lesser extent (OR 2.12, 95 % CI 1.5–5.4, P <0.01 in Asia and OR 1.76, 95 % CI 1.1–2.6, P < 0.01 in South America). Our new ethnic classification showed similar results for Latin America but not for Asian ethnic groups. Only the East Asian group that had the MCP-1 -2518 polymorphism in a homozygote co-dominant and recessive model had an increased risk to develop pTB (OR 3.47, 95 % CI 1.4–8.7, P <0.01 and OR 2.34, 95 % CI 1.3-4.3, P <0.01, respectively). The new classification did not find any association for the Persian and South Asian groups. Neither the new nor the continental group classifications found any association in Africa or any of its ethnic groups (Figs. 4, 5).

New and traditional ethnic classification to assess TB susceptibility in MCP-1 -2518 GG genotype carriers. The homogenous co-dominant model (GG vs AA) shows that people who carry the GG genotype have 3.49 times the risk to develop pulmonary TB compared to people who have the AA genotype. The magnitude of the association in the Asian continent according to the traditional classification appears diluted because it includes South Asia and Persia, which have different ancestry and increase the heterogeneity in this continent. For Latin America, similarly to the traditional ethnic classification, we find that subjects with the GG genotype have 2.72 times the risk to develop pulmonary TB

Ethnic groups and heterogeneity

We found heterogeneity within the ethnic groups from the conventional classification (I 2 73.1 %, P <0.01, for Africa; I 2 83.8 %, P <0.01, for Asia; I 2 90.7 %, P <0.01, for South America). The new ethnic classification showed homogeneity for West Africa and South Asia (I 2 0 %, P = 0.3; I2 0 %, P = 0.5, respectively). We found heterogeneity within Arabia, East Asia and Latin America (I 2 93.5 %, P <0.01; I 2 88.7 %, P <0.01; I 2 91.6 %, P <0.01, respectively). We could not obtain results for South Africa and Persia, since there was only one study in each group.

Discussion

We found an association between the MCP-1 -2518 polymorphism and tuberculosis susceptibility in East Asian and Latin American populations [13, 14, 36]. Previous meta-analyses try to extrapolate this association to the Asian continent. However, since there is ethnic variability within each continent, we cannot generalize this conclusion to every ethnic group. In this way, our meta-analysis groups study populations by using information about migration and linguistics to make ethnic groups more similar. Using this method, we found that an association does not apply to every country in the same continent.

Our new ethnic classification creates ethnic groups (e.g. West Africa and South Asia) with countries sharing similar characteristics. This new classification must be further evaluated with new studies related to genetic susceptibility for infectious and noninfectious diseases.

Regarding TB susceptibility, our new classification, in contrast to the conventional classification, helped to clarify that the association between MCP-1 -2518 A/G polymorphism and pTB is specific for certain populations such as East Asia and Latin America. To our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis that uses a model of genetic susceptibility for pTB to assess if a new ethnic classification based on previous findings about genetic distance, migration and linguistic origins, improves homogeneity within each ethnic groups [13]. Thus, we propose our new classification as a good proxy when genetic markers are not available [17, 37–42].

Previous meta-analyses that use a continental group classification found an association between the MCP-1- 2518 A/G polymorphism and pTB, which is significant for Asia and South America [13, 14]. However, these ethnic groups include countries that are different in terms of ancestry and therefore genetic susceptibility. Our new classification helps to improve homogeneity in South Asia and West Africa. However our new classification does not help us with homogeneity in East Asia and Latin America, where we found association between polymorphism MCP-1 -2518 G allele and pTB. Failure to reach homogeneity could be explained because of gene-gene or gene-environmental interactions. It has been reported that people carrying polymorphism MCP-1 -2518 and MMP-1 -1607 have a higher risk to develop severe TB [12]. The high frequency of G allele observed in cases compared to controls in both East Asia and Latin America might support the hypothesis of a similar ancestry between these two groups [43].

Recent studies from Africa show that the G polymorphism is not common among this population [21, 24]. Human population started in Africa, which means it is the oldest population, and therefore it has had the opportunity to accumulate genetic changes, such as the accumulation of -2518 MCP-1 A allele in its inhabitants that conferred protection and made it possible to adapt to hazardous environmental conditions [44]. We also have to consider other factors influencing TB susceptibility such as malnourishment, socioeconomic, environmental and health factors. The homogeneity found in West Africa cannot be completely explained in our study. We did not assess homogeneity in South Africa, since we only had one study population [22].

To deal with heterogeneity in Asia, we considered three groups: East Asia, South Asia and the Middle East [37–39]. The Asian population started from an “out of Africa” migration 50,000 years ago. It originated from two main migratory routes. The first one moved towards South Asia (India), and the second one to East Asia. Later, Central Asia was populated by Eurasian descendants. This is why we grouped Chinese and Korean populations under the East Asia group, India under the South Asia, and considered Persia under Persia. Also, these study populations have social, educational and mating habits that have that are particular to each group [16, 33, 34, 45]. Our classification groups two similar study populations from India under South Asia. Thus in this setting, it is unlikely that pTB susceptibility is due to the presence of MCP-1 -2518 G polymorphism. In contrast to South Asia, we found an association between this polymorphism and pTB in East Asia where we also found heterogeneity. Interestingly, India (South Asia) and China (East Asia) accounted together for more than 40 % of TB cases worldwide in the last decade [46]. However the implementation of TB control strategies in China has helped decrease prevalence by 50 %, mortality rates by almost 80 % and TB incidence rates by 3.4 % per year between 1990 and 2010 [47]. Thus, even though there is a better control of TB in China, genetic factors might be playing an important role in the development of this disease. In contrast, India maintains its high incidence for the last 10 years, which might be due to a lack of social and public health control rather than genetic factors. It is difficult to assess homogeneity within Persia [48, 49] because we only had one study population. In further meta-analyses about genetic susceptibility we recommend to give a special consideration to Central Asian countries since they share European ancestry and therefore different genetic markers compared to East and South Asia [33].

Latin American ethnic groups that originated from a Han Chinese migration to South America 3000 years ago share HLA markers with this population [50]. This similarity might also explain similar frequency of MCP-1 -2518 G allele and other genetic markers between East Asians and Latin Americans. Since Mexico and Peru share migration, common history, language routes and admixture indexes [40, 51–53], we decided to maintain them in the same ethnic group as previous meta-analyses. However, we consider that for Latin America, we should consider two groups: one of Andean and another of European origin.

The limitations in our study are very common to meta-analyses about genetic association studies. We could not consider environmental and genetic factors that influence this association because this information was not found in the original articles. Thus, for research in multifactorial diseases such as TB, we strongly recommend future studies to include information about malnourishment, socioeconomic factors, BCG and TST status, which could also help to control for heterogeneity.

We obtained homogeneity within South Asia and West Africa, where we can rule out that MCP-1 -2518 polymorphism is associated to susceptibility. However, despite tuberculosis susceptibility found in Latin America and East Asia due to MCP-1 -2518 polymorphism, the populations within each group are still genetically different.

Genetic association studies in populations from Persia, South Africa, South Asia, East Asia and the Americas, where infectious diseases represent a public health problem, will help assess heterogeneity in order to understand the role of ethnicity in genetic susceptibility to these diseases. In the absence of an adequate classification that groups similar genetic characteristics, suitable for understanding genetic susceptibility, our new classification might be a potential proxy for ethnic classification in meta-analysis of genetic association studies when genetic markers are not available.

Conclusions

In summary, using this novel approach, we found an association between the MCP-1 -2518 polymorphism and pTB susceptibility, specifically in Latin American and East Asian populations not detected by using conventional classification. We encourage the use of our new ethnic classification in further genetic association studies for infectious and non-infectious diseases.

Abbreviations

- CCL2:

-

Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2

- CCR2:

-

Chemokine C-C motif receptor

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- HWE:

-

Hardy weinberg equilibrium

- MCP-1:

-

Monocyte chemoattractant protein 1

- MMP-1:

-

Matrix metalloproteinase-1

- mtDNA:

-

Mitochondrial DNA

- NCBI:

-

National Center for Biotechnology Information

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- pTB:

-

Pulmonary tuberculosis

- STREGA:

-

Strengthening the reporting of genetic association studies

- STROBE:

-

Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology

- TB:

-

Tuberculosis

References

Lönnroth K, Raviglione M. Global Epidemiology of Tuberculosis: Prospects for Control. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;29(05):481–91.

Qidwai T, Jamal F, Khan MY. DNA sequence variation and regulation of genes involved in pathogenesis of pulmonary tuberculosis. Scand J Immunol. 2012;75(6):568–87.

Ganachari M, Ruiz-Morales JA, Gomez de la Torre Pretell JC, Dinh J, Granados J, Flores-Villanueva PO. Joint effect of MCP-1 genotype GG and MMP-1 genotype 2G/2G increases the likelihood of developing pulmonary tuberculosis in BCG-vaccinated individuals. PloS one. 2010;5(1), e8881.

Pacheco AG, Cardoso CC, Moraes MO. IFNG +874 T/A, IL10–1082G/A and TNF -308G/A polymorphisms in association with tuberculosis susceptibility: a meta-analysis study. Hum Genet. 2008;123(5):477–84.

Correa PA, Gomez LM, Cadena J, Anaya JM. Autoimmunity and Tuberculosis. Opposite Association with TNF Polymorphism. J Rheumatol. 2005;32(2):219–24.

Tian C, Zhang Y, Zhang J, Deng Y, Li X, Xu D, et al. The +874 T/A polymorphism in the interferon-γ gene and tuberculosis risk: An update by meta-analysis. Hum Immunol. 2011;72(11):1137–42.

Hodge DL, Reynolds D, Cerban FM, Correa SG, Baez NS, Young HA, et al. MCP-1/CCR2 interactions direct migration of peripheral B and T lymphocytes to the thymus during acute infectious/inflammatory processes. Eur J Immunol. 2012;42(10):2644–54.

Tanaka T, Terada M, Ariyoshi K, Morimoto K. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1/CC chemokine ligand 2 enhances apoptotic cell removal by macrophages through Rac1 activation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;399(4):677–82.

Sodhi A, Biswas SK. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1-induced activation of p42/44 MAPK and c-Jun in murine peritoneal macrophages: a potential pathway for macrophage activation. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2002;22(5):517–26.

Flores-Villanueva PO, Ruiz-Morales JA, Song CH, Flores LM, Jo EK, Montano M, et al. A functional promoter polymorphism in monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 is associated with increased susceptibility to pulmonary tuberculosis. J Exp Med. 2005;202(12):1649–58.

Hussain R, Ansari A, Talat N, Hasan Z, Dawood G. CCL2/MCP-I genotype-phenotype relationship in latent tuberculosis infection. PloS one. 2011;6(10), e25803.

Ganachari M, Guio H, Zhao N, Flores-Villanueva PO. Host gene-encoded severe lung TB: from genes to the potential pathways. Genes Immun. 2012;13(8):605–20.

Zhang Y, Zhang J, Zeng L, Huang H, Yang M, Fu X, et al. The -2518A/G Polymorphism in the MCP-1 Gene and Tuberculosis Risk: A Meta-Analysis. PloS one. 2012;7(7), e38918.

Feng WX, Flores-Villanueva PO, Mokrousov I, Wu XR, Xiao J, Jiao WW, et al. CCL2-2518 (A/G) polymorphisms and tuberculosis susceptibility: a meta-analysis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012;16(2):150–6.

Roewer L, Nothnagel M, Gusmao L, Gomes V, Gonzalez M, Corach D, et al. Continent-wide decoupling of chromosomal genetic variation from language and geography in native South Americans. PLoS Genet. 2013;9(4), e1003460.

Foster MW, Sharp RR. Race, ethnicity, and genomics: social classifications as proxies of biological heterogeneity. Genome Res. 2002;12(6):844–50.

Tishkoff SA, Reed FA, Friedlaender FR, Ehret C, Ranciaro A, Froment A, et al. The genetic structure and history of Africans and African Americans. Science. 2009;324(5930):1035–44.

Pagani L, Kivisild T, Tarekegn A, Ekong R, Plaster C, Gallego Romero I, et al. Ethiopian genetic diversity reveals linguistic stratification and complex influences on the Ethiopian gene pool. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;91(1):83–96.

Cooke GS, Hill AV. Genetics of susceptibility to human infectious disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2(12):967–77.

Thye T, Nejentsev S, Intemann CD, Browne EN, Chinbuah MA, Gyapong J, et al. MCP-1 promoter variant -362C associated with protection from pulmonary tuberculosis in Ghana, West Africa. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18(2):381–8.

Velez Edwards DR, Tacconelli A, Wejse C, Hill PC, Morris GA, Edwards TL, et al. MCP1 SNPs and pulmonary tuberculosis in cohorts from West Africa, the USA and Argentina: lack of association or epistasis with IL12B polymorphisms. PloS one. 2012;7(2), e32275.

Moller M, Nebel A, Valentonyte R, van Helden PD, Schreiber S, Hoal EG. Investigation of chromosome 17 candidate genes in susceptibility to TB in a South African population. Tuberculosis (Edinb). 2009;89(2):189–94.

Ben-Selma W, Harizi H, Boukadida J. MCP-1 -2518 A/G functional polymorphism is associated with increased susceptibility to active pulmonary tuberculosis in Tunisian patients. Mol Biol Rep. 2011;38(8):5413–9.

Arji N, Busson M, Iraqi G, Bourkadi JE, Benjouad A, Boukouaci W, et al. The MCP-1 (CCL2) -2518 GG genotype is associated with protection against pulmonary tuberculosis in Moroccan patients. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2012;6(1):73–8.

Alagarasu K, Selvaraj P, Swaminathan S, Raghavan S, Narendran G, Narayanan PR. CCR2, MCP-1, SDF-1a & DC-SIGN gene polymorphisms in HIV-1 infected patients with & without tuberculosis. Indian J Med Res. 2009;130(4):444–50.

Mishra G, Poojary SS, Raj P, Tiwari PK. Genetic polymorphisms of CCL2, CCL5, CCR2 and CCR5 genes in Sahariya tribe of North Central India: an association study with pulmonary tuberculosis. Infect Genet Evol. 2012;12(5):1120–7.

Chu SF, Tam CM, Wong HS, Kam KM, Lau YL, Chiang AK. Association between RANTES functional polymorphisms and tuberculosis in Hong Kong Chinese. Genes Immun. 2007;8(6):475–9.

Yang BF, Zhuang B, Li F, Zhang CZ, Song AQ. The relationship between monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 gene polymorphisms and the susceptibility to pulmonary tuberculosis. Chin J Tuberc Respir Dis. 2009;32(6):454–6.

Xu ZE, Xie YY, Chen JH, Xing LL, Zhang AH, Li BX, et al. Monocyte chemotactic protein-1 gene polymorphism and monocyte chemotactic protein-1 expression in Chongqing Han children with tuberculosis. Chin J Pediatr. 2009;47(3):200–3.

Naderi M, Hashemi M, Karami H, Moazeni-Roodi A, Sharifi-Mood B, Kouhpayeh H, et al. Lack of association between rs1024611 (-2581 A/G) polymorphism in CC-chemokine Ligand 2 and susceptibility to pulmonary Tuberculosis in Zahedan, Southeast Persia. Prague Med Rep. 2011;112(4):272–8.

Gallo V, Egger M, McCormack V, Farmer PB, Ioannidis JP, Kirsch-Volders M, et al. STrengthening the Reporting of observational studies in Epidemiology - Molecular Epidemiology (STROBE-ME): an extension of the STROBE statement. Eur J Clin Investig. 2012;42(1):1–16.

Little J, Higgins JP, Ioannidis JP, Moher D, Gagnon F, von Elm E, et al. STrengthening the REporting of Genetic Association studies (STREGA)--an extension of the STROBE statement. Eur J Clin Investig. 2009;39(4):247–66.

Ramsay M. Africa: continent of genome contrasts with implications for biomedical research and health. FEBS Lett. 2012;586(18):2813–9.

Heyer E, Balaresque P, Jobling MA, Quintana-Murci L, Chaix R, Segurel L, et al. Genetic diversity and the emergence of ethnic groups in Central Asia. BMC Genet. 2009;10:49.

Muro T, Iida R, Fujihara J, Yasuda T, Watanabe Y, Imamura S, et al. Simultaneous determination of seven informative Y chromosome SNPs to differentiate East Asian, European, and African populations. Legal Med. 2011;13(3):134–41.

Gong T, Yang M, Qi L, Shen M, Du Y. Association of MCP-1 -2518A/G and -362G/C variants and tuberculosis susceptibility: a meta-analysis. Infect Genet Evol. 2013;20:1–7.

Colonna V, Boattini A, Guardiano C, Dall'ara I, Pettener D, Longobardi G, et al. Long-range comparison between genes and languages based on syntactic distances. Hum Hered. 2010;70(4):245–54.

Dulik MC, Zhadanov SI, Osipova LP, Askapuli A, Gau L, Gokcumen O, et al. Mitochondrial DNA and Y chromosome variation provides evidence for a recent common ancestry between Native Americans and Indigenous Altaians. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90(2):229–46.

Stoneking M, Delfin F. The human genetic history of East Asia: weaving a complex tapestry. Curr Biol. 2010;20(4):R188–93.

Majumder PP. The human genetic history of South Asia. Curr Biol. 2010;20(4):R184–7.

Abdulla MA, Ahmed I, Assawamakin A, Bhak J, Brahmachari SK, Calacal GC, et al. Mapping human genetic diversity in Asia. Science. 2009;326(5959):1541–5.

Bedoya G, Montoya P, Garcia J, Soto I, Bourgeois S, Carvajal L, et al. Admixture dynamics in Hispanics: a shift in the nuclear genetic ancestry of a South American population isolate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(19):7234–9.

Qin H, Zhu X. Power comparison of admixture mapping and direct association analysis in genome-wide association studies. Genet Epidemiol. 2012;36(3):235–43.

Hill AV. Aspects of genetic susceptibility to human infectious diseases. Annu Rev Genet. 2006;40:469–86.

Tamang R, Singh L, Thangaraj K. Complex genetic origin of Indian populations and its implications. J Biosci. 2012;37(5):911–9.

Watts G. WHO annual report finds world at a crossroad on tuberculosis. BMJ. 2012;345, e7051.

de Colombani P, Dadu A, Dravniece G, Hoffner S, Ilyenkova V, Kovac Z, et al. Review of the national tuberculosis programme in Belarus, 10-21 October 2011. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2012. p. 76.

Fazeli Z, Vallian S. Phylogenetic relationship analysis of Persiaians and other world populations using allele frequencies at 12 polymorphic markers. Mol Biol Rep. 2012;39(12):11187–99.

Fazeli Z, Vallian S. Molecular phylogenetic study of the Persiaians based on polymorphic markers. Gene. 2013;512(1):123–6.

Tokunaga K, Ohashi J, Bannai M, Juji T. Genetic link between Asians and native Americans: evidence from HLA genes and haplotypes. Hum Immunol. 2001;62(9):1001–8.

Reich D, Patterson N, Campbell D, Tandon A, Mazieres S, Ray N, et al. Reconstructing Native American population history. Nature. 2012;488(7411):370–4.

Galanter JM, Fernandez-Lopez JC, Gignoux CR, Barnholtz-Sloan J, Fernandez-Rozadilla C, Via M, et al. Development of a panel of genome-wide ancestry informative markers to study admixture throughout the Americas. PLoS Genet. 2012;8(3), e1002554.

Johnson NA, Coram MA, Shriver MD, Romieu I, Barsh GS, London SJ, et al. Ancestral components of admixed genomes in a Mexican cohort. PLoS Genet. 2011;7(12), e1002410.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Peruvian National Institute of Health. We thank Drs. Kim Hoffman and Cesar Sanchez for reviewing this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors do not disclose any financial and non- financial competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

TVL, MT, HG have equally contributed in the conception and design of the study, have been involved in drafting the manuscript, have given final approval of the version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. TVL and MT have equally contributed in the acquisition of the data and interpretation of results. TVL has been involved in the data analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

This article was conceived when the authors’ affiliation was Instituto Nacional de salud, Lima, Peru.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Vásquez-Loarte, T., Trubnykova, M. & Guio, H. Genetic association meta-analysis: a new classification to assess ethnicity using the association of MCP-1 -2518 polymorphism and tuberculosis susceptibility as a model. BMC Genet 16, 128 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12863-015-0280-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12863-015-0280-2