Abstract

Introduction

Taxis play an important role among public transport modes in China, but there has been very little in-depth research regarding taxi drivers’ crash risk. Thus, this study aimed to develop a quantitative method to predict taxi drivers’ crash risk and identify contributory factors.

Methods

Nine hundred fourty-eight professional taxi drivers in Xi’an, China completed an anonymous, structured face-to-face questionnaire reporting their demographic information, work-related stress, daily risky driving behaviors, and crash experience within the 3 years prior to the survey. A Negative-Binomial regression model was used to predict the risk of personal injury collisions for taxi drivers.

Results

Drivers’ 7 risky driving behaviors (e.g., disregarding red lights, speeding, aggressive driving, driving while sleepy or fatigued, etc.) were significantly and positively related to the risk of personal injury collisions, while driver’s parking at will to pick up/drop off passengers was not a significant predictor of such risk for taxi drivers. Furthermore, driver’s sociodemographic characteristics and level of occupational workload were not found to be significantly correlated with the personal injury crash risk.

Conclusions

Risk traits appear to peak among male taxi drivers who drive more hours per day, pay high management fees, and frequently engage in risky behaviors while driving. These findings provide implications to design potentially useful policy initiatives as well as targeted safety promotion programs to prevent road crashes involving professional taxi drivers.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Today, taxis are an important component of China’s urban public transit network. However, taxi drivers frequently work under extremely stressful and hazardous conditions, including long working hours, frequent driving, and occasional disputes with passengers, all of which increase drivers’ physical and mental stress. A survey in Beijing reported that taxi drivers worked up to 11 h per day and at least 27.8 days per month [1]. Taxi drivers in Tlahuac, Mexico City were found to drive 11.1 h a day behind the wheel [2]. Another survey in Sydney showed that 67% of taxi drivers drove at least 50 h per week [3]. Obviously, taxi drivers’ e daily earnings rely heavily on their driving distance within a scheduled period, so they must spend long hours driving in order to carry more passengers and earn more money. Therefore, it is no surprise that taxi drivers engage in occupational risks while driving.

Many studies have been conducted to examine the significant effect of exposure to hazardous working conditions on taxi drivers’ health and to identify potential risk factors contributing to road crashes, such as drivers’ age, job experience [4], license, type of employment [5], and physical and mental health [3, 6, 7]. Generally, taxi drivers are regularly obliged to work long hours into the late night or early morning and are therefore vulnerable to fatigue or sleepiness while driving [3, 4, 8, 9]. Moreover, occupational illness [10], irregular shifts [3], and income dissatisfaction [11] have also been significantly correlated with taxi drivers’ risk of serious crashes.

Because taxi drivers’ daily earnings depend on their driving distance with occupants, they try to drive faster to save time and carry more passengers; as such, they often commit traffic violations. A study of taxi collisions in Taiwan [12] revealed that 25.6% of the observed drivers committed at least one speeding violation during a one-year period, and the frequency of speeding behavior was significantly related to the driver’s age, years of job experience, daily driven kilometers, number of off-duty days per month, etc. Moreover, taxi drivers who exhibited more passive-aggressive driving behaviors were found to be easily distracted and to have an increased crash risk [13]. A survey in Wuhan, China showed that taxi drivers’ attitudes about driving violations had a serious negative influence on their risky driving behaviors [14].

To date, there have been very few studies regarding taxi drivers’ work-related stress and risky driving behaviors. Understanding the relationship between these factors is essential to devising potential strategies to reduce and prevent road accidents and injuries for taxi drivers. Thus, this research aimed to 1) examine the association between their sociodemographic information, self-reported work-related stress, frequency of risky driving behaviors, and involvement in personal injury collisions; and 2) propose a quantitative model of predicting the potential crash risk among professional taxi drivers.

2 Data collection and processing

2.1 Participants

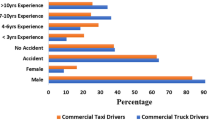

A cross-sectional survey was conducted in Xi’an, China (Fig. 1) between May and July 2015. Initially, a representative sample of 1042 professional taxi drivers with a minimum of 2 years post-license taxi driving experience and an annual working mileage of at least 50,000 km during the past 2 years was selected from 14 taxi companies; however, 94 drivers did not agree to participate in the survey. In total, 948 participants (868 male, 80 female, aged 20–57 years with a mean age = 36.23 years, SE = 8.10 years) were included in the final dataset (response rate = 90.98%). Of the drivers surveyed, 50% held a senior high school diploma or above; 19.62% had received primary school education or below.

2.2 Measures

A questionnaire was designed to examine taxi drivers’ personal views on work-related stress, daily risky driving behaviors, and crash risk. The survey consisted of 16 questions ranging from sociodemographic characteristics, level of workload, frequency of risky driving behaviors and crash experience over the past 3 years.

In the survey, drivers were asked to provide their age (AGE), gender (GEND), and educational background (EDU). Additionally, each participant was encouraged to report his/her average hours of work per day (HOUR) and number of off-duty days per week (DRES) during the past 3 years. Because taxi companies in China charge taxi drivers considerable management fees to cover operational costs, including periodic training and renewal of operating licenses, this survey also required each participant to report his/her company-charged daily management fees (FEE) to capture taxi drivers’ average economic burden.

Taxi drivers’ daily risky driving behavior, including disregarding red lights (REDL), speeding (SPEE), showing annoyance to disliked driver’s behavior by sounding horn or throwing something whatever means (ANNO), aggressive driving like sudden acceleration, deceleration or braking (AGGR), driving while fatigued (FATI), using a mobile phone while driving (PHON), dangerous overtaking (OVTA) and parking at will (PARK), was rated on a 7-point Likert-type scale (0 = never, 1 = hardly ever, 2 = occasionally, 3 = quite often, 4 = frequently, 5 = nearly all the time, and 6 = always) in response to the question, “How often do you commit the following risky driving behavior?”

More specifically, each participant was invited to report his/her own crash experience in personal injury (PIN) collisions over the past 3 years, as shown in Table 1.

2.3 Procedure

Taxi companies selected to conduct the survey were validly registered with the Xi’an Taxi Administrative Office and owned at least 1000 taxis. Registered taxi drivers with a fixed schedule were randomly called to the office to participate in face-to-face interviews with qualified graduate students. Before the interview, each driver was informed of the purpose and definition of each item as well as how to complete the questionnaire. Furthermore, participants were ensured the survey was anonymous and their personal information and individual responses to the questions would be kept strictly confidential. Only those who gave consent were invited to complete the 15-min survey and were compensated 10 CHY for their time.

A Negative-Binomial model was proposed to predict taxi drivers’ risk of being involved in PIN collisions based on their reported sociodemographic information (age, gender, and education level), work-related stress (hours of work per day, off-duty days per week, and daily management fees), and frequency of risky driving behaviors, which was performed in STATA 14 package. Here, p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3 Results

Table 2 presents the variables used in the regression model. Overall, there were high levels of self-reported workload due to long hours of work (M = 9.385, SE = 1.23), inadequate rest (M = 0.325, SE = 0.516), and high management fees (M = 166.74, SE = 17.93). A more detailed examination of responses to workload-related categories revealed that 76.37% of the sample reported having to work 9 h or more per day; 16.67% admitted having to work 8 h per day, and only 6.96% indicated working 7 h or fewer daily. Additionally, more than two-thirds (69.83%) of respondents worked 7 days per week; only 30.17% reported having time to rest. On the other hand, 64.56% were charged 151~ 180 CHY per day as a daily management fee, and another 20.68% were charged 180~ 210 CHY every day.

Moreover, respondents reported that they drove their taxi while sleepy or fatigued more than “quite often” but less than “frequently” (M = 3.272, SE = 1.270), followed by showing annoyance (M = 2.611, SE = 1.083), speeding (M = 2.494, SE = 1.312), running a red light (M = 2.241, SE = 1.359), parking at will to pick up/drop off passengers (M = 2.210, SE = 0.871) and overtaking other drivers under dangerous conditions (M = 2.177, SE = 1.254). Mobile phone use while driving was rated the lowest of all items (M = 1.082, SE = 1.018), consistent with findings from Wang et al. [14].

With regard to taxi drivers’ involvement in crashes during the past 3 years, respondents reported having been involved in 0.308 injury crashes (SE = 0.627). Among the 948 respondents, 17.83% admitted having been involved in one PIN collision and only 5.70% experienced two or more PIN collisions.

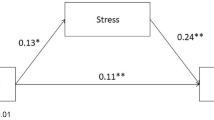

The mean of PIN collisions is 0.308 and the variance is 0.392, and these data therefore contain a small amount of systematic variation. Then a Negative-Binomial regression model was introduced to examine the relationship between taxi drivers’ sociodemographic information (age, gender, and educational background), work-related stress (hours of work per day, off-duty days per week, and daily management fees), frequency of daily risky driving behaviors, and PIN collision involvement, as Table 3 shows.

In Model I, all 14 self-reported variables were collectively entered to determine the predictor of PIN crash rate of taxi drivers, and 7 risky driving behavior variables except parking at will (coef. = 0.025, p = 0.915) were statistically significant predictors of PIN crash risk with all p < 0.05. For simplicity, the significant variables identified in Model I were together collected to determine Model II to predict the PIN crash risk of taxi drivers. Clearly, all risky driving behavior variables were again found to be significant. Compared with Model I, Model II had the better performance of fit (AIC = 755.0 vs. 764.1), but with fewer input independent variables (14 vs. 7).

As mentioned in Model II, positive coefficient is an indication of high risk for injury crashes [15], and thus the frequent behaviors while driving, including running a red light (coef. = 0.521, SE = 0.065), speeding (coef. = 0.241, SE = 0.074), showing annoyance (coef. = 0.154, SE = 0.068), aggressive driving (coef. = 0.276, SE = 0.069), driving while fatigued (coef. = 0.313, SE = 0.031), mobile phone use (coef. = 0.220, SE = 0.057) and dangerous overtaking (coef. = 0.245, SE = 0.055), were identified as the risk factors contributing to PIN collisions among taxi drivers with all p < 0.05, which were consistent with the findings from Wang et al. [15]. These findings should be recommended to their respective taxi companies for occupational safety protection.

4 Conclusions and discussion

Since drivers who drive for work purpose are known to be more prone to a wide range of risks [16], and thus such professional drivers have been reported to have above average crash frequencies compared to personal vehicle drivers as reported in the literature [17]. In Britain, 31% of fatal crashes and 26% of serious injury crashes involve occupational drivers [18]. A survey in Xi’an, China revealed that the average number of taxi crashes per month was 8.500 over the period of 2006 to 2011 [4]. Our previous study also showed that 47.34% of the occupational bus, taxi, lorry, company car and shuttle drivers in Xining, China had caused crashes at some point [19]. Accordingly, it is quite necessary to identify the potential crash risk for these professional drivers.

This questionnaire study tries to investigate for the first time the association between work-related stress, risky driving behaviors and involvement in personal injury crashes using the self-reported data from taxi drivers in Xi’an, China and then determine their predictor of such potential crash risk. Unsurprisingly, taxi drivers aged between 30 and 40 were more likely to be involved in collisions while driving. Because drivers often had young children and elderly parents to care for, they felt compelled to use their time more efficiently by driving faster and transporting more passengers in order to earn more money within a limited time window. Similar findings were reported among taxi drivers in Shanghai and New York City [20].

Additionally, the results found that more than three-quarters of participants had to drive 9 h or more per day, and 18.56% sat behind the wheel up to 11 h or more every day. More concerningly, 69.83% of respondents reported working all week without a day of rest. About three-quarters (74.57%) admitted to drive while sleepy or fatigued “quite often” or more frequently than that. On the other hand, approximately 85% had to pay a daily management fee of 150 CHY to their respective taxi companies, equal to nearly half their total daily gross income; therefore, it is unsurprising that the taxi drivers surveyed engaged frequently in risky behaviors such as speeding, running red lights, overtaking other drivers dangerously, and so on. Since it is impossible to cancel the daily management fee charged by taxi companies, it is strongly demanded to be reduced to some extent.

The results also provide insight into how to prevent and reduce traffic crashes among taxi drivers, namely by increasing their income. Taxi drivers could also be offered taxi ownership and operating rights under the centralized administration of taxi companies. It is worth noting that the government should play a major role in guiding reform to change the taxi industry’s present managerial approach; for example, tax incentives could be given to taxi companies to help subsidize employee benefits (e.g., medical insurance, accident insurance, paid leave, etc.). Taxi companies are strongly suggested to set up special funds to help those engaged in injury crashes. Furthermore, both the government and taxi companies should develop stricter rules and regulations to limit registered drivers’ maximum daily and weekly hours of work, which may help to prevent fatigued driving [21, 22].

On the other hand, taxi drivers should receive education about the dangers of risky driving behaviors to encourage them to obey the traffic rules and avoid serious traffic violations [23], such as speeding and disregarding red lights, etc. Those who disobey the rules should be harshly penalized or have their taxi license revoked. Moreover, employers should be required to improve taxi drivers’ working conditions, including through the establishment of a trade union, purchase of insurance, periodic training and safety education, and mental health exams for all registered taxi drivers. It would also be worthwhile to open a complaint centre through which passengers and drivers could submit grievances and resolve disputes about service problems; a coordinated problem resolution procedure may help to reduce taxi drivers’ risky driving behaviors.

Professional drivers in the world confront the similar excessive workload conditions and considerably high crash risk. A survey in Australia showed that occupational drivers had a higher intention to speed in a work vehicle than their personal one [24], and thus were more likely to have crashes while driving for work. In Sri Lanka, taxi driver’s sociodemographic factors (i.e. level of education, marital status) are also found to be significantly associated with their aggressive driving and risk-taking behaviors [25]. 81% of taxi drivers in Ankara, Turkey reported talking by using hand-held phone while driving [26]. On the other hand, many previous studies reported in the literature show that professional driver’s crash involvement is significantly related to the sociodemographic factors, working conditions or risky driving behaviors [10, 15, 27,28,29]; therefore, the proposed quantitative approach using all these possible contributory factors can be used to examine the potential crash risk for professional drivers (i.e., taxi, bus, coach, truck) in China, European countries and other areas in the world [15, 30]. The findings of this study provide valuable data with important implications for worldwide decision-making in public health policy and traffic regulation for professional drivers.

References

Shi J, Tao L, Li X, Atchley P (2014) A survey of taxi drivers’ risky driving behavior in Beijing. J Transport Safe Secure 6(1):34–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/19439962.2013.799624

Berrones-Sanz LD (2018) The working conditions of motorcycle taxi drivers in Tlahuac, Mexico City. Journal of Transport & Health 8:73–80 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2017.04.008

Dalziel JR, Job R (1997) Motor vehicle accidents, fatigue and optimism bias in taxi drivers. Accid Anal Prev 29(4):489–494. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0001-4575(97)00028-6

Zhao Y, Zhang J, He X (2015) Risk factors contributing to taxi involved crashes: a case study in Xi’an. China Period Polytech Transp Eng 43(4):189–198. https://doi.org/10.3311/PPtr.7742

La QN, Lee AH, Meuleners LB, Duongc DV (2013) Prevalence and factors associated with road traffc crash among taxi drivers in Hanoi. Vietnam Accid Anal Prev 50:451–455 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2012.05.022

Lim M, Chia SE (2015) The prevalence of fatigue and associated health and safety risk factors among taxi drivers in Singapore. Singap Med J 56(2):92–97. https://doi.org/10.11622/smedj.2014169

Wanamo ME, Abaya SW, Aschalew AB (2017) Prevalence and risk factors for low back pain (LBP) among taxi drivers in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: a community based cross-sectional study. Ethiop J Health Dev 31(4):244–250

Cicchino JB, Zuby DS (2017) Prevalence of driver physical factors leading to unintentional lane departure crashes. Traffic Inj Prev 18(5):481–487. https://doi.org/10.1080/15389588.2016.1247446

Wang Y, Li M, Du J, Mao C (2015) Prevention of taxi accidents in Xi’an, China: what matters most? Cent Eur J Public Health 23(1):77–83. https://doi.org/10.21101/cejph.a3931

Montoro L, Useche S, Alonso F, Cendales B (2018) Work environment, stress, and driving anger: a structural equation model for predicting traffic sanctions of public transport drivers. Int J Environ Res Public Health 15(3):497. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15030497

Chen JC, Chang WR, Chang W, Christiani D (2005) Occupational factors associated with low back pain in urban taxi drivers. Occup Med 55(7):535–540. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqi125

Tseng CM (2013) Operating styles, working time and daily driving distance in relation to a taxi driver’s speeding offenses in Taiwan. Acci Anal Prev 52:1–8 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2012.11.020

Sullman MJM, Stephens AN, Kuzu D (2013) The expression of anger amongst Turkish taxi drivers. Accid Anal Prev 56:42–50 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2013.03.013

Ma M, Yan X, Huang H, Abdel-Aty M (2010) Safety of public transportation occupational drivers risk perception, attitudes, and driving behavior. Transport Res Rec 2145:72–79 https://doi.org/10.3141/2145-09

Wang Y, Li L, Prato C (2018) The relation between working conditions, aberrant driving behaviour and crash propensity among taxi drivers in China. Acci Anal Prev https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2018.03.028

Newnam S, Watson B (2011) Work-related driving safety in light vehicle fleets: a review of past research and the development of an intervention framework. Safety Sci 49(3):369–381 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2010.09.018

Downs CG, Keigan M, Maycock G, Grayson GB (1999) The safety of fleet car drivers: A review. Report 390. Transport Research Laboratory, Crowthorne, Berkshire

Reported road casualties Great Britain: annual report 2012, Department for Transport, UK, 2014. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/reported-road-casualties-great-britain-annual-report-2012

Wang Y, Li L, Feng L, Peng H (2014) Professional drivers’ views on risky driving behaviors and accident liability: a questionnaire survey in Xining, China. Transp Lett 6(3):126–135 https://doi.org/10.1179/1942787514Y.0000000019

Huang Y, Sun D, Tang J (2018) Taxi driver speeding: who, when, where and how? A comparative study between Shanghai and New York City. Traffic Inj Prev 19(3):311–316 https://doi.org/10.1080/15389588.2017.1391382

Wang Y, Xin M, Bai H, Zhao Y (2017) Can variations in visual behavior measures be good predictors of driver sleepiness? a real driving test study. Traffic Inj Prev 18(2):132–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/15389588.2016.1203425

Wang Y, Ma C, Li Y (2018) Effects of prolonged tasks and rest patterns on driver’s visual behaviors, driving performance, and sleepiness awareness in tunnel environments: a simulator study. Iran J Sci Technol Trans Civ Eng 42(2):143–151. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40996-018-0093-4

Korn L, Weiss Y, Rosenbloom T (2017) Driving violations and health promotion behaviors among undergraduate students: self-report of on-road behavior. Traffic Inj Prev 18(8):813–819. https://doi.org/10.1080/15389588.2017.1316842

Newnam S, Watson B, Murray W (2004) Factors predicting intentions to speed in a work and personal vehicle. Transp Res Part F Traffic Psychol Behav 7(4–5):287–300 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2004.09.005

Akalanka EC, Fujiwara T, Desapriya E, Peiris DC, Scime G (2012) Sociodemographic factors associated with aggressive driving behaviors of 3-wheeler taxi drivers in Sri Lanka. Asia Pac J Public Health 24(1):91–103 https://doi.org/10.1177/1010539510376304

Darcin M, Alkan M (2015) Safety risk of mobile phone use while driving in sample of taxi drivers. Promet Traffic Transp 27(4):309–315 https://doi.org/10.7307/ptt.v27i4.1597

Rowden P, Matthews G, Watson B, Biggs H (2011) The relative impact of work-related stress, life stress and driving environment stress on driving outcomes. Acci Anal Prev 43(4):1332–1340 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2011.02.004

Ge Y, Qu W, Jiang C, Du F, Sun X, Zhang K (2014) The effect of stress and personality on dangerous driving behavior among Chinese drivers. Acci Anal Prev 73:34–40 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2014.07.024

Vahedi J, Mohaymany AS, Tabibi Z, Mehdizadeh M (2018) Aberrant driving behaviour, risk involvement, and their related factors among taxi drivers. Int J Environ Res Public Health 15(8):1626 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15081626

Havârneanu CE, Măirean C, Popuşoi SA (2019) Workplace stress as predictor of risky driving behavior among taxi drivers. The role of job-related affective state and taxi driving experience. Safety Sci 111:264–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2018.07.020

Acknowledgements

This research is financially supported by the Basic Scientific Research of Central Colleges of Chang’an University (300102218521). The authors also would like to thank all participants for their time and commitment to the survey in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XB designed the study, interpreted results and drafted the manuscript. FZ carried out the survey and performed data analysis. YW helped collected the data and contributed to the interpretation of results. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Ba, X., Zhou, F. & Wang, Y. Predicting personal injury crash risk through working conditions, job strain, and risky driving behaviors among taxi drivers. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 10, 48 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12544-018-0320-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12544-018-0320-x