Abstract

Background

Relieving postoperative pain and prompt resumption of physical activity are of the utmost importance for the patients and surgeons. Infiltration of local anesthetic is frequently used methods of pain control postoperatively. Laparoscopically delivered transversus abdominis plane block is a new modification of ultrasound-guided transversus abdominis plane block.

This study was conducted to compare the efficacy of laparoscopic-guided transversus abdominis plane block with trocar site local anesthetic infiltration for pain control after gynecologic laparoscopy.

Results

No statistically significant difference between the two groups in mean visual analogue scale at 1, 18, and 24 h (P = 0.34, P = 0.41, and P = 0.61, respectively), while the mean visual analogue scale was significantly lower in the laparoscopic-guided transversus abdominis plane block group than in the trocar site local anesthetic infiltration group at 3, 6, and 12 h (P = 0.049, P = 0.011, and P = 0.042, respectively). No statistically significant difference was observed in the cumulative narcotics consumed at 3 h (P = 0.52); however, women with transversus abdominis plane block have consumed significantly less amount of narcotics than women with trocar site infiltration at 6, 12, and 24 h (P = 0.04, P = 0.038, and P = 0.031 respectively). Patient satisfaction was significantly higher in the laparoscopic-guided transversus abdominis plane block group (P = 0.035).

Conclusion

Laparoscopic-guided transversus abdominis plane block is more effective in reduction of both pain scores in the early postoperative period and the cumulative narcotics consumption than trocar site local anesthetic infiltration in gynecologic laparoscopy.

Trial registration

Clinical Trials.gov NCT02973451

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Laparoscopic intervention, with very low mortality, minimal morbidity, fast recovery, the best cosmetic outcome, and the least postoperative pain, has gained a major participation in gynecologic surgery throughout the past two decades [1]. During laparoscopic surgery, inflation of the abdomen provides the surgeon a perfect view of the structures and a room to work [2]. Relieving postoperative pain and prompt resumption of physical activity are of the utmost importance for the patients and surgeons [3]. Block of abdominal wall and infiltration of local anesthetic are frequently used methods of pain control postoperatively [4]. Transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block is a recent regional anesthetic modality that anesthetizes the afferent neural pathway of the anterior abdominal wall. This is mediated through injecting a local anesthetic between the transversus abdominis muscle and the internal oblique muscle [5]. TAP block was shown to be effective means for pain control after open and laparoscopic gynecological surgeries [6]. Laparoscopically delivered TAP block is a new modification of ultrasound-guided TAP block, it allows injection of the local anesthetic in the appropriate place directed by the laparoscopic camera [7]. Local anesthetic infiltration at the site of the surgical wound was validated as a postoperative analgesia [8]. The aim of this study was to compare the efficacy of laparoscopic-guided transversus abdominis plane block with trocar site local anesthetic infiltration for pain control after gynecologic laparoscopy.

Methods

Our prospective single-blinded randomized controlled clinical trial was carried out in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Faculty of Medicine, Zagazig University, after approval by the University Ethics Committee. A written informed consent was provided by all participants.

Inclusion criteria included women who are scheduled for gynecological laparoscopic intervention and18 years old and older. Women with chronic pain syndrome, allergy to local anesthetic, and postoperative intraperitoneal drain and women needed alteration to laparotomy were excluded from the study. Consenting eligible women were allocated randomly to either laparoscopic-guided transversus abdominis plane block or trocar site local anesthetic infiltration. Randomization was created by the computer. Allocation was concealed in opaque, sealed, and serially numbered envelopes. Patients and postoperative assistants were blinded to the procedure while, surgeons and anesthetists were not.

For laparoscopic-guided transversus abdominis plane block group, at the end of the procedure and before release of pneumoperitoneum, laparoscopic camera allowed direct internal visualization of the selected area, between the iliac crest and the costal margin in the midaxillary line, where the TAP block will be inserted. The surgeon introduced a needle through the skin and felt the 2-pops representing the 2 fascial planes. Visualization helped the surgeon to reach the proper space between the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles. If the needle tip exceeded the transversus abdominis muscle and was directly beyond or penetrated the peritoneum, the surgeon should withdraw it back 3–5 mm to be in the correct place. Twenty to 25 ml of 0.25% bupivacaine with epinephrine was injected on each side after an initial negative aspiration. After completing injection, a bulge was demonstrated owing to pooling of the local anesthetic behind transversus abdominis muscles and the peritoneum.

For trocar site local anesthetic infiltration group, 10 ml of 0.25% bupivacaine with epinephrine was injected around the umbilical port opening. Five milliliters was injected around each one of the essential two and any extra 5-mm laparoscopic port openings at the end of the procedure.

Demographic and preoperative data like age, body mass index (BMI), type of operation, and the total operative time were collected. During surgery, all patients received the same intravenous analgesia according to body weight (fentanyl 1.5 mcg /kg) by the anesthesiologist. They did not receive analgesics, immediately after surgery, in the post anesthesia care unit till complete recovery. In the postoperative ward, they received the standard postoperative analgesics. Our department protocol is 1 g intravenous paracetamol every 8 h and intravenous meperidine 20 mg every time the patients need analgesia. Postoperative pain was assessed at 1, 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 h with a 10-point visual analogue scale (VAS), with a range of 0 (indicating no pain) to 10 (indicating the worst pain). The cumulative meperidine consumed on request was calculated at 3, 6, 12, and 24 h. Patient satisfaction was reported on a scale from 0 (indicating very poor satisfaction) and 10 (indicating excellent satisfaction) at 24 h.

The primary outcome was the difference in pain scores at 1, 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 h between the two groups. The secondary outcomes were the difference in the cumulative meperidine consumed at 3, 6, 12, and 24 h, in addition to the difference in patient satisfaction at 24 h between the two groups.

Sample size calculation was based on a previous suggestion that two-point difference in VAS between the two groups would be clinically expressive [9]. With a suggested standard deviation of difference to be 4, each group should contain 34 women to provide this difference with 80% power and statistical significance of 0.05. Five women were added to compensate for an assumed 15% dropout, so at least 39 women should be included in each group.

Results

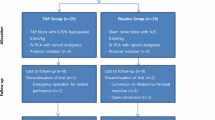

Between May 2016 and June 2017, a total of 105 women were assessed for eligibility. Of them, 90 gave consent for the study. They were allocated randomly to laparoscopic-guided TAP block group (n = 45) or trocar site local anesthetic infiltration group (n = 45). Four women were excluded from analysis due to lack of visual analogue pain scores: one woman in the laparoscopic-guided TAP block group and three women in the trocar site local anesthetic infiltration group. Two women in each group were excluded from analysis due to insertion of intraperitoneal drain (Fig. 1).

Patient flowchart. A total of 105 women were assessed for eligibility. Of them, 90 gave consent for the study. They were allocated randomly to laparoscopic-guided TAP block group (n = 45) or trocar site local anesthetic infiltration group (n = 45). Four women were excluded from analysis due to lack of visual analogue pain scores: one woman in the laparoscopic-guided TAP block group and three women in the trocar site local anesthetic infiltration group. Two women in each group were excluded from analysis due to insertion of intraperitoneal drain

Age, weight, time of operation, and type of operation in both groups were comparable. Patient satisfaction was significantly higher in the laparoscopic guided TAP block group than the trocar site local anesthetic infiltration group (Table 1).

There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups in mean visual analogue scale at 1, 18, and 24 h (P = 0.34, P = 0.41, and P = 0.61, respectively), while mean visual analogue scale was significantly lower in the laparoscopic-guided TAP block group than the trocar site local anesthetic infiltration group at 3, 6, and 12 h (P = 0.049, P = 0.011 and P = 0.042, respectively) (Table 2).

No statistically significant difference was observed in the cumulative meperidine consumed at 3 h between the laparoscopic-guided TAP block group 55 ± 18 mg and the trocar site local anesthetic infiltration group 76 ± 23 mg (P = 0.52). However, cumulative meperidine consumed in TAP block group was significantly less than trocar site infiltration group at 6, 12, and 24 h (P = 0.04, P = 0.038, and P = 0.031 respectively) (Table 3).

Discussion

Opioids, NSAIDs, and paracetamol are effective postoperative analgesics, but their use is not without complications [10]. Inclusion of TAP block in the postoperative multi-modal analgesia protocols has reduced the use of the other analgesics and the related side effects [11].

In the first described TAP block, a blunt needle was introduced blindly through the external and the internal oblique muscles, guided by the double- pop technique. The local anesthetic was injected between the transverse abdominis and the internal oblique muscles. This method has resulted in some penetrative injuries, and sometimes, it fails to gain the proper anesthetic effect [5]. Recently, ultrasound-guided TAP block has increased the efficacy and safety of the procedure through visualization of the needle tip and the local anesthetic injection site [12]. But, the technique needs great skills also; minimal complications have been described [13].

Previous randomized trials have reported the efficacy of the ultrasound-guided TAP block as a postoperative analgesia after open appendectomy, laparoscopic cholecystectomy, and abdominal hysterectomy [14,15,16]. Similarly, it has gained a specific analgesic advantage in gynecologic laparoscopic intervention where tissue trauma and pain were minimal to moderate [17,18,19,20].

Nevertheless, such postoperative analgesic efficacy of ultrasound-guided TAP block was not confirmed, when compared with trocar site local anesthetic infiltration following laparoscopic cholecystectomy [21] and spinal morphine after cesarean delivery [22].

Local anesthetic injection in the neurovascular plane between the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles under laparoscopic vision was first described by Magee et al. [7]. Afterward, Chetwood et al. [23] used a similar method following laparoscopic nephrectomy which was safe and time saving. In addition, laparoscopic-guided TAP block has reduced postoperative pain scores after laparoscopic cholecystectomy [24, 25] and laparoscopic ventral hernia repair [26].

Favuzza and Delaney [27] stated that laparoscopic-guided TAP block has resulted in effective pain relief, reduction in narcotic requirement and short postoperative hospital stay in patients who underwent laparoscopic colorectal surgery. The addition of laparoscopic-guided TAP block to enhanced recovery pathway (ERP) was safe, effective, and allowed early discharge of patients following laparoscopic colorectal surgery [28,29,30].

Postoperative local anesthetic injection into trocar insertion sites after laparoscopic gynecologic surgery has reduced pain scores significantly in early postoperative period compared with placebo [31]. On the other hand, pain scores reduction was not significant [32].

Various studies have compared ultrasound-guided TAP block with trocar site local anesthetic infiltration. The results varied from significant reduction [33] to non-significant reduction [34] in cumulative morphine use at 24 h with TAP blocks compared with local anesthetic infiltration. A recent trial [35] has reported that ultrasound-guided TAP block has no significant clinical benefit over trocar site local anesthetic infiltration in laparoscopic nephrectomy. Huang et al. [36] found that the combination of TAP block and trocar sites local anesthetic infiltration provided better analgesic effect than TAP block alone.

To the best of our knowledge, few trials studied the efficacy of laparoscopic-guided TAP block. In consistence with our results, laparoscopic-guided TAP block decreased both postoperative pain and opioid use after laparoscopic ventral hernia repair [26]. Furthermore, it was safe and efficient analgesic in elderly patients who underwent elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy [25]. On the contrary, El Hachem et al. [37] found that neither laparoscopic-guided TAP block nor ultrasound-guided TAP block offered postoperative analgesic superiority over trocar site local anesthetic infiltration after four ports gynecologic laparoscopy. Although the local anesthetic was injected at the end of operation similar to our study, but this difference in the results could be attributed to the dissimilarity in local anesthetic doses or the special methodology of the other study. Patients were divided into two groups: one group consisted of unilateral anesthesiologist-administeredultrasound-guided TAP block and the other group consisted of unilateral surgeon- administered laparoscopic-guided TAP block. In both groups, the contralateral port sites were infiltrated with local anesthetic. VAS pain score was recorded on the TAP block and contralateral sides, using the patients as their own controls.

Conclusions

In conclusion, laparoscopic-guided TAP block is more effective in reduction of both pain scores in the early postoperative period and cumulative meperidine consumption than trocar site local anesthetic infiltration in gynecologic laparoscopy.

The present study had some limitations, pain scores on movement were not assessed, blinding of surgeons and anesthetists was difficult, and it did not focus on side effects. So, further properly blinded studies containing large number of patients and using different doses of local anesthetic are required to verify these results.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- ERP:

-

Enhanced recovery pathway

- LSH:

-

Laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy

- NSAIDs:

-

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- TAP:

-

Transversus abdominis plane

- TLH:

-

Total laparoscopic hysterectomy

- VAS:

-

Visual analogue scale

References

Nieboer TE, Hendriks JC, Bongers MY, Vierhout ME, Kluivers KB (2012) Quality of life after laparoscopic and abdominal hysterectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 119:85–91

Garry R, Fountain J, Mason S et al (2004) The eVALuate study; two parallel randomised trials, one comparing laparoscopic with abdominal hysterectomy, the other comparing laparoscopic with vaginal hysterectomy. Br Med J 328:129

Kulen FT, Tihan D, Duman U, Bayam E, Zaim G (2016) Laparoscopic partial cholecystectomy: a safe and effective alternative surgical technique in difficult cholecystectomies. Turk J Surg 32:185–190

Bamigboye AA, Hofmeyr GJ (2010) Caesarean section wound infiltration with local anesthesia for postoperative pain relief - any benefit? S Afr Med J 100:313–319

Rafi AN (2001) Abdominal field block: a new approach via the lumbar triangle. Anesthesia 56:1024–1027

Sivapurapu V, Vasudevan A, Gupta S, Badhe AS (2013) Comparison of analgesic efficacy of transversus abdominis plane block with direct infiltration of local anesthetic into surgical incision in lower abdominal gynecological surgeries. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol 29:71–75

Magee C, Clarke C, Lewis A (2011) Laparoscopic TAP block for laparoscopic cholecystectomy: description of a novel technique. Surgeon 9:352–353

Gupta A (2005) Local anesthesia for pain relief after laparoscopic cholecystectomy–a systematic review. Best Pract Res Clin Anesthesiol 19:275–292

Farrar JT, Portenoy RK, Berlin JA, Kinman JL, Strom BL (2000) Defining the clinically important difference in pain outcome measures. Pain 88:287–294

Eslamian L, Jalili Z, Jamal A et al (2012) Transversus abdominis plane block reduces postoperative pain intensity and analgesic consumption in elective cesarean delivery under general anesthesia. J Anesth 26:334–338

Fusco P, Scimia P, Paladini G et al (2015) Transversus abdominis plane block for analgesia after cesarean delivery. A systematic review. Minerva Anestesiol 81:195–204

Lancaster P, Chadwick M (2010) Liver trauma secondary to ultrasound-guided transversus plane block. Br J An esth 104:509

Sandeman DJ, Bennett M, Dilley AV et al (2011) Ultrasound-guided transversus abdominis plane blocks for laparoscopic appendicectomy in children: a prospective randomized trial. Br J Anesth 106:882–886

Niraj G, Searle A, Mathews M, Misra V, Baban M, Kiani S et al (2009) Analgesic efficacy of ultrasound-guided transversus abdominis plane block in patients undergoing open appendicectomy. Br J Anesth 103:601–605

El-Dawlatly AA, Turkistani A, Kettner SC, Machata AM, Delvi MB, Thallaj A et al (2009) Ultrasound-guided transversus abdominis plane block: description of a new technique and comparison with conventional systemic analgesia during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Anesth 102:763–767

Carney J, McDonnell JG, Ochana A, Bhinder R, Laffey JG (2008) The transversus abdominis plane block provides effective postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing total abdominal hysterectomy. Anesth Analg 107:2056–2060

De Oliveira GS Jr, Fitzgerald PC, Marcus RJ, Ahmad S, McCarthy RJ (2011) A dose-ranging study of the effect of transversus abdominis block on postoperative quality of recovery and analgesia after outpatient laparoscopy. Anesth Analg 113:1218–1225

Pather S, Loadsman JA, Gopalan PD, Rao A, Philp S, Carter J (2011) The role of transversus abdominis plane blocks in women undergoing total laparoscopic hysterectomy: a retrospective review. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 51:544–547

Champaneria R, Shah L, Geoghegan J, Gupta JK, Daniels JP (2013) Analgesic effectiveness of transversus abdominis plane blocks after hysterectomy: a meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 166:1–9

Kawahara R, Tamai Y, Yamasaki K, Okuno S, Hanada R, Funato T (2015) The analgesic efficacy of ultrasound-guided transversus abdominis plane block with mid-axillary approach after gynecologic laparoscopic surgery: a randomized controlled trial. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol 31:67–71

Ortiz J, Suliburk JW, Wu K, Bailard NS, Mason C, Minard CG et al (2012) Bilateral transversus abdominis plane block does not decrease postoperative pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy when compared with local anesthetic infiltration of trocar insertion sites. Reg Anesth Pain Med 37:188–192

McMorrow RC, Ni Mhuircheartaigh RJ, Ahmed KA, Aslani A, Ng SC, Conrick-Martin I et al (2011) Comparison of transversus abdominis plane block vs spinal morphine for pain relief after Caesarean section. Br J Anesth 106:706–712

Chetwood A, Agrawal S, Hrouda D, Doyle P (2011) Laparoscopic assisted transversus abdominis plane block: a novel insertion technique during laparoscopic nephrectomy. Anesthesia 66:317–318

Elamin G, Waters PS, Hamid H, O'keeffe HM, Waldron RM, Duggan MS (2015) Efficacy of a laparoscopically delivered transversus abdominis plane block technique during elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective, double-blind randomized trial. J Am Coll Surg 221:335–344

Tihan D, Totoz T, Tokocin M, Ercan G, Calikoglu TK, Vartanoglu T (2016) Efficacy of laparoscopic transversus abdominis plane block for elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy in elderly patients. Bosn J Basic Med Sci 16:139–144

Fields AC, Gonzalez DO, Chin EH, Nguyen SQ, Zhang LP, Divino CM (2015) Laparoscopic-assisted transversus abdominis plane block for postoperative pain control in laparoscopic ventral hernia repair: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Coll Surg 221:462–469

Favuzza J, Delaney CP (2013) Laparoscopic-guided transversus abdominis plane block for colorectal surgery. Dis Colon Rectum 56:389–391

Favuzza J, Delaney CP (2013) Outcomes of discharge after elective laparoscopic colorectal surgery with transversus abdominis plane blocks and enhanced recovery pathway. J Am Coll Surg 217:503–506

Alvarez MP, Foley KE, Zebley DM, Fassler SA (2014) Comprehensive enhanced recovery pathway significantly reduces postoperative length of stay and opioid usage in elective laparoscopic colectomy. Surg Endosc 29:1–6

Keller DS, Ermlich BO, Delaney CP (2014) Demonstrating the benefits of transversus abdominis plane blocks on patient outcomes in laparoscopic colorectal surgery: review of 200 consecutive cases. J Am Coll Surg 219:1143–1148

Selcuk S, Api M, Polat M, Arinkan A, Aksoy B, Akca T et al (2016) Effectiveness of local anesthetic on postoperative pain in different levels of laparoscopic gynecological surgery. Arch Gynecol Obstet 293:1279–1285

Tam T, Harkins G, Wegrzyniak L, Ehrgood S, Kunselman A, Davies M (2014) Infiltration of bupivacaine local anesthetic to trocar insertion sites after laparoscopy: a randomized, double blind, stratified, and controlled trial. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 21:1015–1021

Park JS, Choi GS, Kwak KH, Jung H, Jeon Y, Park S (2015) Effect of local wound infiltration and transversus abdominis plane block on morphine use after laparoscopic colectomy: a nonrandomized, single-blind prospective study. J Surg Res 195:61–66

Bava EP, Ramachandran R, Rewari V, Chandralekha, Bansal VK, Trikha A (2016) Analgesic efficacy of ultrasound guided transversus abdominis plane block versus local anesthetic infiltration in adult patients undergoing single incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Anesth Essays Res 10:561–567

Araújo AM, Guimarães J, Nunes CS, Couto PS, Amadeu E (2017) Post-operative pain after ultrasound transversus abdominis plane block versus trocar site infiltration in laparoscopic nephrectomy: a prospective study. Rev Bras Anestesiol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjan.2016.08.008

Huang S, Mi S, He Y, Li Y, Wang S (2016) Analgesic efficacy of trocar sites local anesthetic infiltration with and without transversus abdominis plane block after laparoscopic hysterectomy: a randomized trial. Int J Clin Exp Med 9:6518–6524

El Hachem L, Small E, Chung P, Moshier EL, Friedman K, Fenske SS et al (2015) Randomized controlled double-blind trial of transversus abdominis plane block versus trocar site infiltration in gynecologic laparoscopy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 212:182.e1–182.e9

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our unit’s residents and nurses for help.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IAE and EHN participated in the project development and data collection. EAM and AAM participated in the data collection and manuscript writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Authors’ information

I A Elsharkwy: His fields of interest are laparoscopy and feto-maternal medicine. Has many papers published in the field of obstetrics and gynecology.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

-

Ethical Approval: The study was approved by the ethics Committee of Zagazig University

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

-

Statement of human rights: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

El sharkwy, I.A., Noureldin, E.H., Mohamed, E.A. et al. Laparoscopic-guided transversus abdominis plane block versus trocar site local anesthetic infiltration in gynecologic laparoscopy. Gynecol Surg 15, 15 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s10397-018-1047-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s10397-018-1047-3