Abstract

The pre-Alpine history of the Venaco-Ghisoni Unit, a continental unit belonging to the Alpine Corsica (France), was reconstructed on the basis of U–Pb dating of zircon and allanite. Zircon was separated from a metagranitoid and an epidote-bearing metagabbro and analyzed by Laser Ablation Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS). Magmatic ages ranging from 291 to 265 Ma were obtained for the metagranitoid samples and 276.9 ± 1.1 Ma for the epidote-bearing metagabbro. This geochronological dataset, combined with field observations, microstructural and cathodoluminescence analysis demonstrate that in the Early Permian, the Variscan basement of the Venaco-Ghisoni Unit was intruded first by the granitoid and then by the gabbro. Allanite was identified in the metagranitoid and exhibit an U–Pb age of 225 ± 8 Ma. We interpret this age as reflecting metamorphism associated to the Late Triassic rifting predating the opening of the Piemonte-Liguria Ocean. The absence of middle Eocene—Oligocene zircon and allanite overgrowths is compatible with the low metamorphic conditions (< 350–400 °C) recorded by the Venaco-Ghisoni Unit during Alpine metamorphism.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

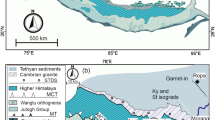

The Alpine Corsica consists of a stack of oceanic and continental units that record a complex geodynamic history (Fig. 1). This history started at the end of the Variscan orogeny, developed through rifting and spreading stages that caused the opening of the Piemonte-Liguria Ocean and ended with subduction and collision during the Alpine orogeny (Durand-Delga 1984; Egal 1992; Malavieille et al. 1998; Marroni and Pandolfi 2003; Molli 2008; Molli and Malavieille 2011; Di Rosa et al. 2020).

a Geographic framework of the Corsica Island. The location of the Hercynian Corsica (HC) and the Alpine Corsica (AC) is indicated. b Geological setting of Central Corsica. Within the Hercynian Corsica (HC): the Corsica-Sardinia Batholith products are differentiated following Cocherie et al. (2005) (U1, U2 and U3 suites); Rb Roches Brunes Fm., Ec Eocene deposits. Within the Alpine Corsica (AC) the three main groups of tectonic units are indicated: the Lower Units (LU undifferentiated Lower Units, TU Tenda Unit, CP Cima Pedani Units, Ca Caporalino Unit, GHU Venaco-Ghisoni Unit), the Schistes Lustrés Complex (SL undifferentiated Schistes Lustrés Complex) and the Upper Units (Ba Balagne nappe, SD Serra-Debbione Unit, Pi Pineto Unit, SLU Santa Lucia Unit). Early Miocene deposits (Fb Francardo Basin, Ap Aleria Plane) and Quaternary deposits (Qd) are also indicated. CCSZ Central Corsica Shear Zone. Yellow stars indicate the areas sampled for this work

Several magmatic and metamorphic events took place during the orogenic collapse of the Variscan belt in response to lithospheric thinning (triggering the rise of the hot asthenospheric mantle) in an extensional regime. The associated crustal thinning and continental rifting evolved in the Middle Jurassic towards complete oceanization with the initiation of seafloor spreading ca. 165 Ma (e.g., Lardeaux and Spalla 1991; Marotta and Spalla 2007; Müntener and Hermann 2001; Schuster and Stüwe 2008). The European continental margin corresponding to the future Briançonnais and internal massif domains (e.g., Ballèvre et al. 2018) was largely affected by this diffuse magmatic activity associated with high temperature/medium-low pressure (HT/M-LP) metamorphism (e.g., Paquette et al. 1989; Cenki-Tok et al. 2011; Manzotti et al. 2012). Magmatism and metamorphism were associated with extensional structures such as shear zones, which accommodated the thinning of the continental crust (Beltrando et al. 2010; Manatschal and Müntener 2009; Mohn et al. 2011).

Traces of post-Variscan magmatism are also preserved in the Alpine Corsica, which is regarded as the southward extension of the collisional belt of the Western Alps (e.g., Mattauer et al. 1981; Durand-Delga 1984). This anorogenic magmatism is considered to be part of the Corsica-Sardinia batholith and involved magmatic intrusions within the European continental margin from the Visean to the Middle Permian (Cabanis et al. 1990; Ménot 1990; Paquette et al. 2003; Cocherie et al. 2005; Rossi et al. 2015 and references therein) before the onset of the Alpine cycle (Bonin et al. 1987). Intrusive rocks are mainly preserved in their original intrusive settings (i.e., in the Hercynian Corsica), but relics of these bodies, which were variably deformed and metamorphosed during the Alpine orogeny, are also found in the north-eastern sector of the island (i.e., in the Alpine Corsica). A few lines of evidence of Permian HT metamorphism associated with rifting were discovered in the Western Alps (e.g. Vavra et al. 1996; Kunz et al. 2018) but are not documented so far in Corsica.

In this contribution, we investigate the geological evolution recorded by the continental units of Corsica from the end of the Variscan Orogeny and the opening of the Piemonte-Liguria Ocean in the Late Carboniferous to Middle Jurassic. We performed in situ U–Pb dating by LA-ICP-MS of zircon and allanite from metagranitoid and metagabbro samples of the Venaco-Ghisoni Unit (Lower Units, Alpine Corsica). This tectonic unit includes a wide variety of the pre-Mesozoic lithotypes known in Corsica (i.e., metagranitoid, metagabbro, mafic dykes) that have never been dated before. Therefore, this study is the first geochronological study related to the pre-Alpine history performed on the Lower Units. The geochronological results were combined with meso- and microstructural investigations to constrain the Permo-Triassic evolution of the European thinned continental margin in the southernmost extension of the Alpine belt.

2 Tectonic setting

The geology of Corsica has been subdivided into two geological domains known as the Hercynian and Alpine Corsica (Fig. 1a; e.g., Durand-Delga 1984). The Hercynian Corsica represents a remnant of the European continental margin. This domain mainly consists of Permo-Carboniferous plutonic rocks (i.e., the Corsica-Sardinia batholith in Rossi et al. 2015) intruded into a Palaeozoic metamorphic basement, with rare sedimentary covers ranging in age from Permian to middle-late Eocene (Amaudric du Chaffaut 1980; Di Rosa et al. 2019a). The Permo-Carboniferous magmatic products are grouped into three suites (U1, U2 and U3) based on their age and compositional variability (Rossi et al. 2015 and reference therein). The U1 suite consists of Mg–K-rich intrusions formed in the Early Carboniferous (~ 340 Ma, Paquette et al. 2003), whose composition ranges from monzonite to granite, with associated ultrapotassic basic rocks. This suite has the same geochemical and isotopic composition as the external crystalline massif of the Central Alps (e.g., Aar-Gotthard; Rossi et al. 2015). The U2 suite is mostly composed of calc-alkaline leucocratic biotite-bearing monzogranites of Late Carboniferous-Early Permian age (308–275 Ma, Rossi et al. 2015), which are associated with dacites and rhyolites also belonging to the U2 suite. Finally, the U3 suite consists of peralkaline to slightly peraluminous A-type granites of Early Permian age (290–280 Ma; Cocherie et al. 2005). These intrusives are predominantly dominated by amphibole-biotite granites and pink biotite-bearing granites that are coeval with mafic sequences of tholeiitic affinity. The three suites U1, U2 and U3 are crosscut by mafic and silicic dyke swarms of Early Permian age (Rossi et al. 2015).

The Alpine Corsica consists of a stack of continental and oceanic units that experienced deformation and metamorphism during subduction and syn-convergence exhumation in response to the Late Cretaceous-Middle Eocene closure of the Piemonte-Liguria Ocean and subsequent late Eocene-early Oligocene continental collision (Di Rosa et al. 2020 and references therein). The thinned European margin was subducted below the orogenic wedge beginning in the late Eocene and exhumed before the early Miocene (Maggi et al. 2012; Malasoma and Marroni 2007; Molli 2008; Molli et al. 2017).

The Alpine Corsica includes three groups of tectonic units, from bottom to top: (1) the Lower Units representing the thinned European continental margin that was involved in the subduction/collision. Peak metamorphism reached blueschist facies conditions and was followed by retrogression under greenschist facies (Bezert and Caby 1988; Di Rosa et al. 2017, 2019b, 2020; Malasoma and Marroni 2007; Molli et al. 2006; Molli 2008). (2) The Schistes Lustrés complex consists of ophiolites and oceanic/transitional sequences. Peak metamorphism reached blueschist to eclogite facies conditions (Maggi et al. 2012; Rossetti et al. 2015; Vitale Brovarone et al. 2011). (3) The Upper Units (i.e., Nappes Supérieures of Durand-Delga 1984) include Middle to Late Cretaceous ophiolitic units associated with slices of Late Cretaceous carbonate turbidites. These units recorded only lower-greenschist facies metamorphic conditions (Marroni and Pandolfi 2003; Pandolfi et al. 2016). We also include the Santa Lucia Unit in this group (Fig. 1b), which is characterized by a Permian basement made of granulite complex and granitoids covered by Cretaceous sediments (Marroni and Pandolfi 2007 and references therein). However, the pre-orogenic history of this unit is still a matter of debate.

The NNW-SSE-trending tectonic boundary between the Hercynian and Alpine Corsica marks the thrusting of the Alpine Corsica onto the Hercynian Corsica (Durand-Delga 1984). This tectonic boundary was partially reworked by the Central Corsica Shear Zone (CCSZ, Fig. 1), a sinistral strike-slip system that originated during the late Eocene-early Oligocene convergence (Lacombe and Jolivet 2005; Marroni et al. 2019).

3 Field data and petrography

3.1 Geology of the study area

This study is focused on two metagranitoid samples and one metagabbro sample belonging to the Venaco-Ghisoni Unit (GHU), a tectonic unit forming part of the Lower Units (Di Rosa et al. 2019b). This unit crops out in Central Corsica close to the boundary with the Hercynian Corsica in the area between the villages of Venaco and Ghisoni (Figs. 1, 2, 3). The GHU is an elongated NNW-SSE trending body that is structurally delimited by steep shear zones from the Hercynian Corsica located underneath and from the Schistes Lustrés complex at its top. The GHU mainly consists of metagranitoids and minor volumes of metagabbro intruded in the Roches Brunes Fm. (Variscan polymetamorphic rocks, Durand-Delga 1984). Early Permian leucocratic and mafic dykes (Rossi et al. 2015) crosscut the metagranitoid and metagabbro. The Roches Brunes Fm. and its Permo-Carboniferous intrusions are uncorfomably covered by a Permian meta-volcano-sedimentary complex (i.e., Metavolcanic and Metavolcaniclastic Fm., Figs. 2, 3).

The Alpine polyphase deformation history includes three ductile phases (D1, D2 and D3) that have been described by Garfagnoli et al. (2009) and Di Rosa et al. (2019b). The metagranitoid and metagabbro samples are characterized by a subvertical S1–S2 composite foliation, resulting from the transposition of an older foliation (S1 foliation) by the main foliation (S2 foliation). Several top-to-west shear zones associated with the D2 phase are locally present within the GHU and close to its tectonic contacts. At the microscale, the S1–S2 foliation exhibits protomylonitic to mylonitic fabrics and is marked by elongated clasts of Pl, Qz and K-Fsp (mineral abbreviations are from Whitney and Evans 2010, except for K-white mica, Kwm) wrapped by a fine-grained recrystallized matrix of Qz + Ab + Kwm + Chl (Fig. 4). The P–T conditions prevailing during the D1 and D2 phases were calculated by Di Rosa et al. (2019b) based on Chl-Ph local equilibria in the metapelites of GHU. The results range from 0.81–0.39 GPa, 263–245 °C for D1 and 0.37–0.13 GPa, 228–209 °C for D2. The D3 phase is characterized by open and asymmetric F3 folds and by a S3 foliation gently dipping towards the W. The A3-fold axes trend from NNE to SSW. Pre-existing structures and tectonic contact with the Schistes Lustrés complex were folded during the D3 phase. At the microscale, the D3 phase is only observed in the thick phyllosilicate-rich layers as symmetric microfolds. The last brittle event linked to the CCSZ activity resulted in a strong reworking of the tectonic contacts between the different units (Figs. 2, 3).

Microphotographs of the lithotypes sampled in the Fium’Orbo valley: metagranitoid (CMD37) with a parallel and b crossed Nicols. The S1–S2 mylonitic foliation (normal to the long side of the pictures) is the anisotropy marked by the phyllosilicates wrapping the Qz and Fsp porphyroclasts. In the pictures related to the epidote-bearing metagabbro (CMD50E), with c parallel and d crossed Nicols, the S1–S2 mylonitic foliation (parallel to the long side of the pictures) is marked by the Chl layers alternated to those made of Cpx and Fsp. Large Cpx crystal are partially replaced by Ep and Chl

In the Venaco area (Fig. 2), the metagranitoid volume is crosscut by 1 to 5 m thick mafic dykes. Centimetre-thick layers of the host rock metapelites are preserved within the metagranitoid. Deformation markers resulting from the ductile phases (D1–D3) and from the CCSZ are well recognizable in the field through careful analysis of the displacement that affected the contacts between the metagranitoid and the mafic dykes (Fig. 2b).

In the Ghisoni area (Fig. 3), a 150 m thick layer of epidote-bearing metagabbro is associated with the metagranitoid. This metagabbro layer is found at the contact between the metagranitoid and the host rock (i.e., the Roches Brunes Fm.) and are cross contact cut by leucocratic dykes (< 3 m thick). At the outcrop scale, there is evidence that the metagranitoid and the metagabbro were deformed together (Fig. 3a), whereas no magma mixing between them is observed. The contact between the metagranitoid and the metagabbro is well exposed along Ghisoni-Sampolo road (D344) and consists of an alteration of metagabbro and metagranitoid within a 20 m thick band (Fig. 3a, b).

3.2 Petrography of the sampled rocks

The studied metagranitoid samples [samples CMD33(43), CMD122A and CMD37] are pink biotite-bearing gneisses with monzogranitic compositions (i.e., suite U3 of Rossi et al. 2015). The S1–S2 composite foliation represents the main anisotropy recognizable in thin section. Protomylonitic to mylonitic fabrics are marked by Pl, Ab and Qz porphyroclasts surrounded by a matrix made of Chl, Kwm and thin grains of Ab and Qz (Figs. 4a, b, 5). The metagranitoid is made of Qz (35 vol%), San (30%), Ab (25%) and Chl (5%) that replaced former magmatic Bt. The remaining 5 vol% includes Kwm, minor Ep and accessory minerals such as Aln, Ap, Ttn and Zrn (Fig. 4a, b). Metagranitoids were sampled in two different localities: south of Venaco village (Lat: 42°22′77″ N; Long: 9°17′62″ E, Fig. 2) and in the Fium’Orbo valley, east of Ghisoni village (Lat: 42°10′39″ N; Long: 9°26′19″ E, Fig. 3). Samples CMD33(43) and CMD122A (from Venaco, Fig. 2) were collected along the contact with a mafic dyke composed of Cpx, Pl, Amp, less abundant Qz and accessory minerals such as Ep and Aln. Within the metagranitoid (CMD122A), large crystals of Aln (up to 250 µm) associated to Ab, Chl and Ep were observed along the contact with the mafic dyke (Fig. 5c, d). Allanite crystals occur as subhedral to anhedral grains with microfractures filled by Ep, Chl, Qz and Ap (Fig. 5d). Sometimes Ap occurs along the rim of the Aln crystal and within Ab. In this sample, the magmatic Cpx are fractured and locally replaced by Chl and Pl; the degree of replacement seems to be slightly higher in the immediate surrounding of Aln (Fig. 5c). Sample CMD37 (from Ghisoni, Fig. 3) is a metagranitoid cropping out between the undeformed granitoid (suite U2) of the Hercynian Corsica towards the west and the epidote-bearing metagabbro towards the east. The composition of this sample is similar to those of Venaco [i.e., sample CMD33(43)] in terms of mineral assemblage (Qz: 35 vol%, San: 25%, Ab: 25%, Kwm: 5%, Chl: 5%, and the remaining 5 vol% includes Ep, Aln, Ap, Ttn and Zrn) and microstructures.

Microphotograph of metagranitoid sampled in the Venaco area (CMD122A): a parallel Nicols. b Crossed Nicols. Red circles indicate the spots position. c, d BSE images of the allanite crystals analyzed. In a–c, yellow dashed line indicates the contact between the metagranitoid (on the left) and the mafic dyke (on the right)

The epidote-bearing metagabbro (sample CMD50E) shows a complex texture that is characterized by an alteration of metagabbro and epidote-rich layers (Fig. 3d). This layering is parallel to the S1-S2 foliation (Figs. 3d, 4c, d). Metagabbro is made of Pl (35 vol%), Cpx (10%), Fsp (Ab, K-Fsp, 15%), Ep (10%), Chl (10%), Kwm (10%) and Qz (5%); the remaining 5 vol% includes opaque oxides, Ap and Zrn (Fig. 4c, d). Grains of Cpx (augite) occur in the mylonitic layers as euhedral crystals partially replaced by Ep and Chl; the matrix of these layers is made of Pl, Chl and Qz. Subhedral crystals of Ab and Pl are observed, while Qz occurs as aggregates. Sub-rounded Ep crystals with high relief and high interference colours are associated with augite.

Zircon was separated for U–Pb dating from two metagranitoid samples [CMD33(43) from Venaco and CMD37 from Ghisoni] and the epidote-bearing metagabbro (CMD50E from Ghisoni). The Aln analyzed in this work was found in thin sections of metagranitoids (CMD122A) sampled in the Venaco area. In this sample, the primary contact between the metagranitoid and the mafic dykes is observed (Fig. 5).

4 Analytical methods

4.1 Zircon LA-ICP-MS dating

Zrn crystals were recovered from two metagranitoid samples and one metagabbro sample at the University of Geneva (Switzerland). The samples were crushed using a jaw crusher, and grains < 500 µm were sieved to separate the fractions between 70 and 250 µm. Magnetic grains were removed using a Frantz magnetic separator. Then, Zrn grains were concentrated using methylene iodide. Finally, approximately 70 crystals from each of the samples were hand-picked under a binocular microscope and mounted in epoxy resin. The mounts were polished to expose the crystal interiors and imaged by cathodoluminescence (CL) using a JEOL JSM-7001F Schottky scanning electron microscope at the University of Geneva. In situ Zrn U–Pb isotope analysis was performed at the Institute of Earth Sciences at the University of Lausanne (Switzerland) using a Thermo ELEMENT XR sector field ICP-MS coupled with a UP-193FX ArF 193 nm excimer ablation system (ESI). Data were acquired in time-resolved, peak-jumping, pulse-counting mode utilizing a routine where 30 s of background measurement were followed by 30 s of sample ablation. Laser-induced fractionation of Pb and U was minimized during analysis by employing a soft ablation regime using a repetition rate of 5 Hz and an energy density of ~ 3 J/cm2 per pulse. The laser spot size was 30 μm. The measurement protocol and the parameters used for tuning the mass spectrometer followed Ulianov et al. (2012). Laser-induced elemental fractionation and instrumental mass discrimination were corrected by normalization to the reference Zrn GJ-1. To test the accuracy and external reproducibility of the obtained age data, Plešovice Zrn (Sláma et al. 2008) was measured as a secondary reference material after every ~ 8 unknowns (Table 1). The Plešovice analyses gave a 238U–206Pb weighted average age of 337.5 ± 0.6 Ma (σ, n = 21; MSWD = 0.66). Six of the twenty-one analyses did not pass the 10% discordancy test (Table 1); a weighted mean obtained using spots within the 10% concordance range resulted in a 238U–206Pb age of 337.9 ± 0.4 Ma (σ, n = 15, MSWD = 0.55). Both calculated ages were consistent, within uncertainty, with the ID-TIMS value reported by Sláma et al. (2008). All raw data from Lausanne were processed using the LAMTRACE software package (Jackson 2008), and no common Pb correction was applied. Common Pb was dealt with by monitoring 201Hg and 204(Hg + Pb) as well as (204Pb + 204Hg)/206Pb ratios. The homogeneity of the ablated material was confirmed by monitoring the 206Pb/238U and 207Pb/235U vs. time spectra, and fluctuations in these ratios were interpreted to represent mixing between different age populations within the crystals. Spectra with mixed domains were subsequently discarded and are not reported in Table 1.

Zrn crystals were analyzed by LA-ICP-MS (Table 1). U–Pb data are presented in concordia diagrams. A weighted average 206Pb/238U age was determined for the metagranitoid and metagabbro samples, considering only the date calculated from the sub-concordant analysis. Only the analyses that had a concordance value between 90 and 110% were considered for calculating the weighted mean age of each sample.

4.2 Allanite in situ dating by LA-ICP-MS

One metagranitoid sample (CMD122A) was selected for in situ U–Pb dating of Aln. This LREE-rich epidote usually hosts high concentrations of Th and U, forming the basis of its utility as a geochronometer (Engi 2017).

Dating was performed on Aln (in situ on polished thin section) at the Institute of Geological Sciences of the University of Berne (Switzerland) using a GeoLas Pro 193 nm ArF excimer laser combined with an Elan DRC-e ICP-MS. The analytical procedure follows Burn et al. (2017). Each analysis involved short pre-ablation with a spot diameter of 32 µm, a blank measurement of 60 s and 40 s of ablation using an energy density of 2.5 J/cm2, repetition rate of 9 Hz and spot size of 24 µm (see Additional file 1). Aerosol transport from the ablation cell to the plasma was performed using a gas mixture of He (1 L/min) and H2 (0.08 L/min). The instrument was optimized to increase the sensitivity of heavy masses, keeping oxide production of ThO/Th+ lower than 0.5%. Plešovice Zrn (Sláma et al. 2008) was used as the primary standard, and SISS Aln was used as the secondary standard (von Blanckenburg 1992). The primary reference material Plešovice returned a weighted average 232Th/208Pb age of 335.7 ± 6.9 Ma (2σ, MSWD = 0.2; 16/16 analyses) and a weighted average 238U/206Pb age of 336.9 ± 1.9 Ma (2σ, MSWD = 0.6; 16/16 analyses). The weighted average common lead-corrected ages of SISS were 31.2 ± 0.4 Ma (2σ, MSWD = 1.2; 6/6 analyses) for the 232Th/208Pb system and 39.0 ± 6 Ma (2σ, MSWD = 0.3; 4/6 analyses) for the 238U/206Pb system, which are in agreement and within the uncertainty of previous results (Gregory et al. 2007; von Blanckenburg 1992). Data reduction was carried out using a non-matrix matched standardization technique implemented in the in-house software TRINITY (Burn et al. 2017).

Trace element analysis of Aln was performed at the Institute of Geological Sciences (University of Bern) using a LA-ICP-MS GeoLas Pro 193 nm ArF excimer laser coupled to an Elan DRC-e quadrupole ICP-MS. A gas mixture of He–H2 (1 and 0.008 L/min) was used for aerosol transport. Allanite trace element analyses were performed with laser beam diameters of 24 and 32 µm, frequencies of 10 Hz and energy densities on the sample of ~ 5.0 J/cm2. Allanite analyses were calibrated using GSD-1Gg (Jochum et al. 2005), and accuracy was monitored using the reference material NIST SRM 612 (Jochum et al. 2011). Data reduction was performed using the SILLS software package (Guillong et al. 2008), and LOD values were obtained with the method of Pettke et al. (2011). Further information on the instrument setup is reported in Additional file 1: allanite data.

5 Results

5.1 Zircon texture and U–Pb geochronology

Zrn crystals from sample CMD33(43) are 50–450 µm in size, colourless and elongate, euhedral to sub-euhedral in shape (Fig. 6a, Additional file 2: additional analyzed zircons). Under CL, many grains are characterized by homogeneous or faintly zoned interiors surrounded by fine-scale oscillatory zoned rims sometimes thickened towards the tips. Inherited cores were only detected in a few cases. Few crystals are metamictic.

Zircons CL images and dated spots of the samples a CMD33(43) (metagranitoid from Venaco), b CMD37 (metagranitoid from Ghisoni) and c CMD50E (epidote-bearing metagabbro from Ghisoni). Green: spots whose value passed the < 10% discordancy test; red: spots whose value did not pass the < 10% discordancy test

Similarly, Zrn crystals from the metagranitoid sampled in Ghisoni (CMD37, Additional file 2: additional analyzed zircons) are 35–450 µm in size, are colourless, euhedral and range from stubby to elongate. A subset of grains exhibits core-to-rim oscillatory zoning or complex zoning with intermediate resorption fronts and dark overgrowths (Fig. 6b, Additional file 2: additional analyzed zircons). Although thin bright rims have been observed in some cases, clear evidence of metamorphic overgrowth is missing.

Zrn grains from the epidote-bearing metagabbro (sample CMD50E, Fig. 6c, Additional file 2: additional analyzed zircons) are transparent to translucent and generally larger than Zrn crystals in the metagranitoid (reaching up to 580 µm). They are subhedral to anhedral and mostly elongated. Under CL, grains show a characteristic alteration of broad dark and bright bands. Most grains are characterized by large homogeneous or faintly zoned interiors surrounded by one or more rims exhibiting oscillatory zoning. Dark patches due to metamictization are common, in some cases associated with microfractures. Interiors are either bright or dark and do not show any evidence of resorption.

Twenty-five spot analyses were performed on Zrn interiors and rims from the two metagranitoid samples [eighteen from sample CMD37 and seven from sample CMD33(43), Fig. 7a and Table 1]. These analyses yielded apparent dates that plot along the concordia line between 265 and 291 Ma, with most of the data clustering at ca. 288 Ma. No difference between the two samples is observed, and thus, these samples are plotted together. No systematic difference in dates between cores and rims was observed. Most of the data are discordant, and only eleven analyses passed the < 10% discordancy test. These Zrn spot analyses from the two metagranitoid samples yielded 206Pb/238U weighted mean ages of 282.4 ± 0.9 Ma (σ, n = 11, MSWD = 7.0). The MSWD is significantly higher than 1, indicating a high degree of scattering in the U–Pb data; therefore, the age does not represent a single population. Therefore, the age range 291–265 Ma is considered as the best approximation for the crystallization age of the metagranitoid samples (Fig. 7a).

a Concordia diagram related to the metagranitoids samples: green ellipsoids are related to sample CMD37 (n = 18) from Ghisoni, those grey to sample CMD33(43) (n = 7) from Venaco. b Concordia diagram related to the metagabbro sample (CMD50E, n = 30) from Ghisoni. c Weighted average diagram of sample CMD50E (n = 11)

Thirty spot analyses were performed on Zrn interiors and rims from the metagabbro sample CMD50E. The 206Pb/238U dates range from 244 to 284 Ma, with 90% of them between 272 and 284 Ma (Fig. 7b). Eleven spot analyses passed the < 10% discordancy test (Fig. 7c). A 206Pb/238U weighted mean performed on these dates gave an age of 276.9 ± 1.1 Ma (σ, n = 11, MSWD = 0.82), which was interpreted as the crystallization age of sample CMD50E.

6 Allanite texture and U–Th–Pb geochronology

Aln crystals of sample CMD122A were found in both the mafic dykes and the hosting metagranitoid, even if they were larger and more abundant in the metagranitoid along the contact with the mafic dykes. In thin section, light brown Aln crystals occurred in the metagranitoid within the mylonitic foliation together with Chl, Ab, Qz and Ep (Fig. 5), probably belonging to the clinozoisite subgroup (Armbruster et al. 2006). Observations based on BSE images do not reveal compositional zoning within the Aln crystals. Internal fractures are filled by a mixture of Chl, Ep, Ap and Ttn (Fig. 5). The crystal size is up to 250 µm, much greater than that of other minerals within the contact. This textural evidence, together with its “altered” aspect, suggests that Aln is a porphyroclast.

The dating results for sample CMD122A are summarized in Fig. 8 and Table 2. Following the strategy highlighted in previous studies (Burn et al. 2017; Giuntoli et al. 2018a; Airaghi et al. 2019; Santamaría-López et al. 2019), data were plotted in (1) an uncorrected Tera-Wasserburg diagram to estimate the 207Pb/206Pb common lead composition; (2) a Th-isochron diagram; and (3) common lead-corrected U–Pb ages using the common lead compositions determined from (1). The uncertainties in the common lead fractions f206 and f208 obtained from each regression were propagated through all the computations using a Monte Carlo technique.

The nineteen spot analyses performed on the Aln located along the boundary between the metagranitoid and the mafic dyke yielded an apparent U–Pb weighted average common lead-corrected age of 225 ± 8 Ma (n = 16, MSWD = 2.8). This age is compatible with the lower intercept U–Pb age of 225 ± 10 Ma and the Th-isochron age of 236 ± 14 Ma. The initial common lead compositions are in line with the values from the model of Stacey and Kramers (1975). As the MSWD value is lower than 3, the U–Pb weighted average common lead-corrected age is interpreted as reflecting a single age population.

Trace element data for Aln of sample CMD122A and a comparison with literature data are provided in Figs. 9 and 10. The analyses used for U–Pb dating have low Th/U values ranging between 0.6 and 9.8 and a relatively low fraction of initial lead 206Pb (f206) between 0.22 ± 0.03 and 0.59 ± 0.6 (Fig. 9). This Aln is enriched in LREE compared to HREE with a pattern showing a gentle slope toward the heavier REE and a minor Eu anomaly (Fig. 10, Additional file 3: Decision tree for the classification model).

Allanite classification based on their Th/U ratio and the fraction of initial 206Pb (f206) values. Typical uncertainties for f206 values are between 10 and 20% (2σ, see Additional file 1). a Database of allanite data. Black squares indicate magmatic allanite (344 analyses). Central-Alpine Bergell intrusion: granodiorite BONA—tonalite SISS (Gregory et al. 2007, 2012; Airaghi et al. 2019; Santamaría-López et al. 2019); Atesina Volcanic Complex (AVC): rhyolite (Gregory et al. 2007); Cima D'Asta Pluton (CAP) granodiorite (Gregory et al. 2007; unpublished data); Ecstall Pluton: granodiorite BC (Gregory et al. 2007, 2012); Berridale Batholith, southeast Australia: granodiorite TARA (Gregory et al. 2007, 2012); Sesia Zone: orthogneiss (Giuntoli et al. 2018b); Central Alps: metatonalite—metagranodiorite—metagranite—metadiorite (Gregory et al. 2012). Grey circles indicate metamorphic allanite (including 525 analyses of low-pressure allanite and 686 high-pressure). Sesia Zone: mica schist—metaquartzite—blueschist—eclogite—Glaucophane-epidote schist—orthogneiss—leucogneiss (Regis et al. 2014; Giuntoli et al. 2018b; Vho et al. 2020); Austroalpine basement: pegmatites (Hentschel et al. 2020); Nevado-Filábride metamorphic complex: mica schist (Santamaría-López et al. 2019); Western Alps: metagranite, Mont Blanc (Cenki-Tok et al. 2014) and micaschist, Acceglio Zone (unpublished data); Longmen Shan: metapelites (Airaghi et al. 2018, 2019); Himalaya: metapelites (Goswami-Banerjee and Robyr 2015; unpublished data); Central Alps: metapelites (Janots et al. 2009; Janots and Rubatto 2014); metatonalite—metagranodiorite—metagranite—metadiorite (Gregory et al. 2012). Red circles indicates Aln analyzed in this study. b Visualization of the predictions of a machine learning classification model produced using the Random Forest algorithm including bootstrap aggregating (See Additional file 3: Decision tree for the classification model). A classification three containing 107 nodes was refined and used as a predictive model. The allanite data produced in this study (red dots) are 100% classified as “metamorphic” by the model. The classification accuracy is above 95% based on the out-of-bagging error calculation

Chondrite-normalized REE patterns of allanite of sample CMD122A. Magmatic allanite: “1” (thick black band) is from Gregory et al. (2012) and “2” (thin grey line) is from Renna et al. 2007. Metamorphic allanite are “3” from Regis et al. (2014), “4” from Boston et al. (2017) and “5” from Vho et al. (2020). Dashed blue line “6” indicates magmatic monazite. Red lines indicate allanite crystals studied in this work

7 Discussion

7.1 Age of the intrusions

The oscillatory zoning observed in Zrn from the metagranitoid suggests a magmatic origin (Pidgeon 1992 and references therein). Even though the samples come from a tectonic unit showing a complex polyphase deformation history marked by dynamic recrystallization (Di Rosa et al. 2019b), Zrn do not have visible metamorphic rims. The Zrn ages from the metagranitoid (265–291 Ma) and the epidote-bearing metagabbro (276.9 ± 1.1 Ma) are interpreted as magmatic ages. In light of this results, it appears that the epidote-bearing metagabbro is not part of the oldest magmatic suite U1 (~ 340 Ma) that includes ultrapotassic basic rocks (Rossi et al. 2015), as proposed by Di Rosa et al. (2019b).

Zrn grains from the metagranitoid have 206Pb/238U dates scattered between 265 and 291 Ma, without any clear relationship between cores and rims. Populations of Zrn grains extracted from individual samples of dacite-rhyolites and granitoids commonly record crystal growth over 104–106 years (e.g.Samperton et al. 2015; Farina et al. 2018), with these age ranges being the result of crystallization in long-lived and vertically extensive magma storage zones (Cashman et al. 2017). However, the age range observed for the metagranitoid (26 Ma) is incompatible with such short time rates. This age range rather suggests that the observed scatter was caused by Pb mobility probably linked to the emplacement of the metagabbro at ca. 275 Ma, or even later during the Triassic or during the Alpine orogeny. As suggested by several studies (e.g.Ashwal et al. 1999; Spencer et al. 2016; Bolle et al. 2018; Tedeschi et al. 2018), prolonged high-temperature conditions following the crystallization of magmatic Zrn can trigger Pb mobility, generating a significant scatter of dates along the concordia. This effect can be particularly severe for Zrn grains younger than ca. 400 Ma, where the limited curvature of the concordia line and the lower precision of the 207Pb measurement limits the identification of discordance (Spencer et al. 2016). Magmatic Zrn U–Pb age smearing along the concordia line has been observed in many Precambrian igneous bodies belonging to high-temperature terrains (e.g., Bolle et al. 2018). Although it is impossible to define a statistically sound magmatic age for the metagranitoid rock, the 291–265 Ma range presented here overlaps with the age of the A-type granites (290–280 Ma, Paquette et al. 2003; Cocherie et al. 2005) that characterized the last magmatic event recorded in the Corsica-Sardinia batholith (U3 suite of Rossi et al. 2015).

The epidote-bearing metagabbro outcropping in the Ghisoni area was not described, and no age data were available. Other mafic rocks associated with the Permo-Carboniferous batholith occur in several localities on Corsica Island (i.e., the mafic–ultramafic and dioritic complex of Cocherie et al. 2005). Ohnestetter and Rossi (1985) proposed that stratified complexes of troctolite, olivine gabbro, gabbro-norite and diorite of the Tenda, Pila-Canale and Levie localities formed between 290 and 280 Ma. The undeformed gabbro-granite complex formation of Porto is dated at 281 ± 3 Ma (Renna et al. 2007). In this complex, magma mingling and magma mixing textures observed in the field suggest that the mafic rocks were intruded within a not completely solidified granitic mush. This setting seems to be a common feature in Corsica, where, as already observed by Cocherie et al. (2005), most of the crystallization ages obtained from mafic rocks are younger than those obtained from granites and andesites. The concordia age calculated for Zrn of the epidote-bearing metagabbro (276.9 ± 1.1 Ma) is in line with the emplacement age obtained in the other localities, for example, the Porto gabbro in the Hercynian Corsica (Renna et al. 2007).

The U–Pb Zrn crystallization age of the metagabbro falls in the lower range of the Zrn dates obtained for the metagranitoid (Fig. 7). As discussed above, we propose that the intrusion of the metagabbro triggered Pb mobility in the Zrn crystals of the granitoids partially affecting the age record. The geochronological results suggest that the emplacement of the metagranitoid preceded the intrusion of the metagabbro. The absence of meso-scale features supporting magma mixing suggests that the granitoid magma was already solidified when the gabbro intruded.

Our geochronological data confirm that the U3 suite event, including calc-alkaline acidic and mafic rocks, occurred between 286 and 275 Ma. According to Paquette et al. (2003), this event probably took place at middle- to low-crustal levels and through several discrete and short-lived episodes, each of them with a duration of less than 5 Ma. Owing to the lack of additional geochemical analysis, crustal contamination of the epidote-bearing metagabbro, as established by Tribuzio et al. (2009) for the Bocca di Tenda olivine-gabbronorites, can only be assumed.

7.2 An attempt to interpret the allanite age

Aln is a common LREE-rich accessory phase that is observed in a wide variety of magmatic and metamorphic rocks ranging from greenschist facies (Smith and Barreiro 1990; Tomkins and Pattinson 2007) to blueschist-eclogite facies (Janots et al. 2006; Rubatto et al. 2011; Giuntoli et al. 2018a) and amphibolite facies (Janots et al. 2009; Airaghi et al. 2019; Santamaría-López et al. 2019; Boston et al. 2017).

The biggest crystals of Aln surrounded by Chl are observed in thin section (sample CMD122A, Fig. 5) along a thin band of ca. 500 µm at the boundary between a mafic dyke and the hosting metagranitoid (sample CMD122A). These Aln crystals yield a common lead-corrected U–Pb age of 225 ± 8 Ma. This Triassic age is ca. 50 My younger than the U–Pb Zrn age of metagranitoid and metagabbro reported above, and both have been interpreted to reflect the age of intrusion. Such discrepancies cannot be explained by different closure temperatures, as the Aln closure temperature is above 750 °C (Oberli et al. 2004). The large size of the dated crystals (up to 250 µm) and the greyish-brownish color are features common to Aln of magmatic origin. However, the younger intrusion ages of post-Variscan batholiths in Corsica are restricted to the Permian (Cocherie et al. 2005; Renna et al. 2007; Rossi et al. 2015). Therefore, this Aln age remains enigmatic and cannot be clearly linked to magmatism for the metagranitoid. An Alpine origin can be also excluded, as mixing ages would result in a much larger spread of dates between the Permian and Oligocene (e.g., Cenki-Tok et al. 2011).

Two attempts were made to further elucidate the origin of the Aln. Low Th/U ratios associated with low fractions of initial 206Pb indicate a metamorphic origin when compared with a database containing 1555 analyses of Aln from various origins (Fig. 9). The predictive model trained on this dataset using bootstrap aggregating classified 100% of the analyses as magmatic (N = 18). Trace element analyses are reported in Fig. 10 and compared with data from the literature. The steep REE patterns are distinct from metamorphic Aln forming in metasediments (Boston et al. 2017; Vho et al. 2020) and from magmatic Aln from white granites (Renna et al. 2007), but show similarities with magmatic Aln from metatonalites (Gregory et al. 2012) and metamorphic Aln from micaschist (Regis et al. 2014). Boston et al. (2017) reported similar REE patterns for metamorphic Aln in gneiss (their sample Ba0901) and orthogneiss (samples LEP0979, LEP0980) from the Central Alps. This result illustrates the effect of different bulk rock compositions on the REE pattern of Aln and prevent trace element systematic to be used to decipher the origin of this Aln. As, this age cannot be clearly associated with a regional magmatic event and as the Aln were classified as metamorphic based on their Th/U ratio and f206 values, we tentatively attribute it to a metasomatic/metamorphic event during Permo-Triassic extension.

7.3 Geodynamic implications

Corsica Island is the southeastern continuation of the Alpine belt, thus preserving large exposures of the remnants of the European continental margin in both its Alpine and Hercynian domains (Durand-Delga 1984; Egal 1992; Malavieille et al. 1998; Molli and Malavieille 2011; Marroni et al. 2017; Di Rosa et al. 2020). This margin represented the northwestern edge of the Piemonte-Liguria Ocean, whose opening is the result of a long-lived history and developed from continental thinning up to seafloor spreading (Lavier and Manatschal 2006; Marroni and Pandolfi 2007; Péron-Pinvidic and Manatschal 2009; Mohn et al. 2012; Ribes et al. 2019). The Middle Jurassic opening of this oceanic basin is in fact achieved by a history starting in the Permian and developed by pure-shear extension coupled with magmatic activity that predated a magma-poor rifting stage (Mohn et al. 2012).

In the Alpine belt, igneous activity and high-temperature metamorphism are attributed to a Permo-Triassic high geothermic regime, as described by many authors in several tectonic units derived from both passive Europe and Adria continental margins (Lardeaux and Spalla 1991; Quick et al. 1992; Gardien et al. 1994; Vavra et al. 1996; Colombo and Tunesi 1999; Tribuzio et al. 1999; Schaltegger and Brack 2007; Peressini et al. 2007; Roda and Zucali 2008; Manzotti et al. 2012, 2017, 2018; Schaltegger et al. 2015). This regime was associated with the development of several extensional basins controlled by high-angle normal faults (Winterer and Bosellini 1981; Bernoulli et al. 1990; Bertotti et al. 1993). The anomalous geothermic regime and coeval extensional tectonics are regarded as the result of mantle upwelling occurring under the continental crust (Hermann and Müntener 1996; Lardeaux and Spalla 1991; Marotta and Spalla 2007; Trommsdorff et al. 1993). This model was confirmed by several stratigraphic and tectonic studies devoted to the Permo-Triassic inheritance (Manatschal and Müntener 2009; Beltrando et al. 2010; Mohn et al. 2011; Vitale Brovarone et al. 2014) and by metamorphic and petrochronological data collected throughout the Alpine belt, for instance, in the Western Alps (Lardeaux and Spalla 1991; Gardien et al. 1994; Manzotti et al. 2012; Kunz et al. 2018), the Eastern and Southern Alps (Thöni and Miller 2009; Beltrán-Trivino et al. 2016), the Malenco Valley (Hermann and Rubatto 2003) and the Ivrea Zone (Vavra et al. 1996; Zanetti et al. 2016; Langone et al. 2017). According to Marotta and Spalla (2007), this regime was the precursor of the Mesozoic oceanization that resulted in the birth of the Piemonte-Liguria Ocean during the Middle Jurassic. In this framework, several studies indicated that the first evidence of strong, differential subsidence associated with normal faulting was recorded in the Late Triassic (Berra 1995; Chevalier 2002). In addition, thermochronological data from the European Alps point to the existence of a large-scale crustal heating event during the Late Triassic–Early Jurassic. For instance, a heating event at the boundary between the Late Triassic and Early Jurassic is registered in the Ligurian Alps (Decarlis et al. 2017) as well as in the Western Alps (Beltrando et al. 2015) and in the Northern Calabrian Arc (Liberi et al. 2011). According to Chenin et al. (2019), this heating event of the continental crust is the result of a high heat flow produced by the early necking of the upper mantle during the inception of the rifting process. These authors also suggested that the existence of a heat pulse during the early stages of crustal necking without the need for large-offset normal faults can only be explained by viscoelastoplastic necking of the upper mantle.

In contrast to the Alpine belt, no detailed reconstruction of the pre-orogenic history is available for Corsica Island. Most of the available geochronological data for the pre-orogenic history of the Hercynian Corsica were mainly devoted to the assessment of the magmatic ages (emplacement and crystallization). As previously reported, the Zrn U–Pb data for these events range between 270 and 290 Ma (Paquette et al. 2003; Cocherie et al. 2005; Renna et al. 2007), which are in good agreement with the data presented in this paper. Similar ages were obtained from the lower and upper continental crust preserved in some tectonic units of the Alpine Corsica (Martin et al. 2011; Seymour et al. 2016). In addition, Seymour et al. (2016) reported Early to Middle Jurassic (200–160 Ma) U–Pb ages for Rt and Ap sampled in the lower crust section of the Santa Lucia Unit. In this unit, the same ages were obtained for the Zrn overgrowths around Permian cores. These data are interpreted as a consequence of heating associated with the rifting of the European margin of Alpine Corsica. However, the same authors have also shown the occurrence of Zrn overgrowth with U–Pb ages spanning from the Middle to Late Triassic (220 to 240 Ma). These ages overlap with our U–Pb Aln ages. However, a comparison between these data must be performed with caution, mainly because the Venaco-Ghisoni and Santa Lucia Units occur in different tectonic settings within the Alpine Corsica, and consequently, their correlation remains debated (Durand-Delga 1984; Marroni and Pandolfi 2007; Molli and Malavieille 2011; Meresse et al. 2012). Regardless of their spatial distribution, the presence of Late Triassic ages can be regarded as valuable insight for the reconstruction of the pre-orogenic thermal history in Alpine Corsica. For a full understanding of the magnitude and temperature of the thermal pulse, further data are required. We can only postulate that the Late Triassic U–Pb age of Aln reflects metamorphism linked to the inception of rifting, which subsequently led to the opening of the Piemonte-Liguria Ocean.

8 Conclusion

In this work, we provide geochronological data that are used to refine the pre-Alpine history of the Venaco-Ghisoni Unit (GHU), a continental unit derived from the European margin and involved in Alpine subduction and collision in the middle Eocene–Oligocene. Zrn separated from two metagranitoid samples and one metagabbro sample yielded crystallization ages (metagranitoid: 265–291 Ma, metagabbro: 276.9 ± 1.1 Ma) that overlap with the Early Permian emplacement age proposed for suite U3 of the Corsica-Sardinia Batholith. The wide scatter of Zrn dates in the metagranitoid is probably caused by a distribution of the U/Pb system and Pb mobility, which took place during the intrusion of the metagabbro at ca. 277 Ma.

The Aln grains, occurring along the boundary between a mafic dyke and the hosting metagranitoid, could have registered metamorphism at 225 ± 8 Ma. Although the effects of Mesozoic pre-Alpine rifting were already identified in the Alpine belt, such a Late Triassic Triassic metamorphism was never reported in the Alpine Corsica.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Airaghi, L., Janots, E., Lanari, P., de Sigoyer, J., & Magnin, V. (2019). Allanite petrochronology in Fresh and Retrogressed garnet-biotite metapelites from the Longmen Shan (Eastern Tibet). Journal of Petrology, 60(1), 151–176. https://doi.org/10.1093/petrology/egy109

Airaghi, L., Warren, C. J., de Sigoyer, J., Lanari, P., & Magnin, V. (2018). Influence of dissolution/reprecipitation reactions on metamorphic greenschist to amphibolite facies mica 40Ar/39Ar ages in the Longmen Shan (eastern Tibet). Journal of Metamorphic Geology, 36, 933–958.

Amaudric du Chaffaut, S. (1980). Les unités alpines a la marge orientale du massif cristallin corse (p. 6). Thèse de doctorat Sciences Naturelles: Université Pierre et Marie Curie-Paris.

Armbruster, T., Bonazzi, P., Akasaka, M., Bermanec, V., Chopin, C., Gieré, G., et al. (2006). Recommended nomenclature of epidote-group minerals. European Journal Mineralogy, 18, 551–567.

Ashwal, L. D., Tucker, R. D., & Zinner, E. K. (1999). Slow cooling of deep crustal granulites and Pb-loss in zircon. Geochimica et. Cosmochimica Acta, 63, 2839–2851.

Ballèvre, M., Manzotti, P., & Dal Piaz, G. V. (2018). Pre-Alpine (Variscan) inheritance: A key for the location of the future Valaisan Basin (Western Alps). Tectonics, 37, 786–817. https://doi.org/10.1002/2017TC004633

Beltrando, M., Compagnoni, R., & Lombardo, B. (2010). (Ultra-) high-pressure metamorphism and orogenesis: An Alpine perspective. Gondwana Research, 18, 147–166.

Beltrando, M., Stockli, D. F., Decarlis, A., & Manatschal, G. (2015). A crustal-scale view at rift localization along the fossil Adriatic margin of the Alpine Tethys preserved in NW Italy. Tectonics, 34, 1927–1951. https://doi.org/10.1002/2015TC003973

Beltrán-Triviño, A., Winkler, W., von Quadt, A., & Gallhofer, D. (2016). Triassic magmatism on the transition from Variscan to Alpine cycles: Evidence from U-Pb, Hf, and geochemistry of detrital minerals. Swiss Journal of Geosciences, 109(3), 309–328. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00015-016-0234-3

Bernoulli, D., Bertotti, G., & Froitzheim, N. (1990). Mesozoic faults and associated sediments in the Austroalpine-South Alpine continental margin. Memorie della Società Geologica Italiana, 45, 25–38.

Berra, F. (1995). Stratigraphic evolution of a Norian intraplatform basin recorded in the Quattervals Nappe (Austroalpine, Northern Italy) and paleogeographic implications. Eclogae Geologicae Helvetiae, 88(3), 501–528.

Bertotti, G., Picotti, V., Bernoulli, D., & Castellarin, A. (1993). From rifting to drifting: Tectonic evolution of the South-Alpine upper crust from the Triassic to the Early Cretaceous. Sedimentary Geology, 86, 53–76.

Bezert, P., & Caby, R. (1988). Sur l’age post-bartonien des événements tectonométamorphiques alpins en bordure orientale de la Corse cristalline (Nord de Corte). Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France, 4(6), 965–971.

Bolle, O., Diot, H., Vander Auwera, J., Dembele, A., Schittekat, J., Spassov, S., et al. (2018). Pluton construction and deformation in the Sveconorwegian crust of SW Norway: Magnetic fabric and U–Pb geochronology of the Kleivan and Sjelset granitic complexes. Precambrian Research, 305, 247–267.

Bonin, B., Platevoet, B., & Vialette, Y. (1987). The geodynamic significance of alkaline magmatism in the Western Mediterranean compared with West Africa. Geological Journal, 22, 361–387.

Boston, K. R., Rubatto, D., Hermann, J., Engi, M., & Amelin, Y. (2017). Geochronology of accessory allanite and monazite in the Barrovian metamorphic sequence of the Central Alps, Switzerland. Lithos, 286–287, 502–518.

Burn, M., Lanari, P., Pettke, T., & Engi, M. (2017). Non-matrix-matched standardisation in LA-ICP-MS analysis: General approach, and application to allanite Th–U–Pb dating. Journal of Analytical Atomic Spectrometry, 32, 1359–1377. https://doi.org/10.1039/C7JA00095B

Cabanis, B., Cochemé, J. J., Vellutini, P. J., Joron, J. L., & Treuil, M. (1990). Post-collisional Permian volcanism in northwestern Corsica: An assessment based on mineralogy and trace-element geochemistry. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research, 44, 51–67.

Cashman, K. V., Sparks, R. S. J., & Blundy, J. D. (2017). Vertically extensive and unstable magmatic systems: A unified view of igneous processes. Science, 355, eaag3055.

Cenki-Tok, B., Darling, J. R., Rolland, Y., Dhuime, B., & Storey, D. (2014). Direct dating of mid-crustal shear zones with synkinematic allanite: New in situ U–Th–Pb geochronological approaches applied to the Mont Blanc massif. Terra Nova, 26, 29–37.

Cenki-Tok, B., Oliot, E., Rubatto, D., Berger, A., Engi, M., Janots, E., et al. (2011). Preservation of Permian allanite within an Alpine eclogite facies shear zone at Mt Mucrone, Italy: Mechanical and chemical behavior of allanite during mylonitization. Lithos, 125, 40–50.

Chenin, P., Picazo, S., Jammes, S., ManatschalMüntener, G. O., & Karner, G. (2019). Potential role of lithospheric mantle composition in the Wilson cycle: A North Atlantic perspective. Geological Society, 470, 157–172.

Chevalier, F. (2002). Vitesse et cyclicite de fonctionnement des failles normales de rift, implication sur le remplissage stratigraphiques des bassins et sur les modalites d’extension d’une marge passive fossile. Application au demi-graben de Bourg d’Oisans (Alpes Occidentales, France). Thesis, Université de Bourgogne, Dijon (France), p. 313.

Cocherie, A., Rossi, P., Fanning, C. M., & Guerrot, C. (2005). Comparative use of TIMS and SHRIMP for U-Pb zircon dating of A-type granites and mafic tholeiitic layered complexes and dykes from the Corsican batholith (France). Lithos, 82, 185–219.

Colombo, A., & Tunesi, A. (1999). Pre-Alpine metamorphism in the southern Alps. Schweizerische Mineralogische und Petrographische Mittelungen, 78, 163–168.

Decarlis, A., Fellin, M. G., Maino, M., Ferrando, S., Manatschal, G., Gaggero, L., et al. (2017). Tectono-thermal evolution of a distal rifted margin: Constraints from the Calizzano massif (Prepiedmont-Brianconnais domain, Ligurian Alps). Tectonics, 36, 3209–3228.

Di Rosa, M., De Giorgi, A., Marroni, M., & Vidal, O. (2017). Syn-convergence exhumation of continental crust: Evidence from structural and metamorphic analysis of the Monte Cecu area, Alpine Corsica (Northern Corsica, France). Geological Journal, 52, 919–937.

Di Rosa, M., Frassi, C., Marroni, M., Meneghini, F., & Pandolfi, L. (2019). Did the “Autochthonous” European foreland of Corsica Island (France) experience Alpine subduction? Terra Nova, 32, 34–43.

Di Rosa, M., Frassi, C., Meneghini, F., Marroni, M., Pandolfi, L., & De Giorgi, A. (2019). Tectono-metamorphic evolution in the European continental margin involved in the Alpine subduction: New insights from the Alpine Corsica, France. Comptes Rendus Geoscience, 351(5), 384–394.

Di Rosa, M., Meneghini, F., Marroni, M., Frassi, C., & Pandolfi, L. (2020). The coupling of high-pressure oceanic and continental units in Alpine Corsica: Evidence for syn-exhumation tectonic erosion at the roof of the plate interface. Lithos, 354–355, 105328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lithos.2019.105328

Durand-Delga, M. (1984). Principaux traits de la Corse Alpine et correlations avec les Alpes Ligures. Memorie della Società Geologica Italiana, 28, 285–329.

Egal, E. (1992). Structures and tectonic evolution of the external zone of Alpine Corsica. Journal of Structural Geology, 14(10), 1215–1228.

Engi, M. (2017). Petrochronology based on REE-minerals: Monazite, allanite, xenotime apatite. Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry, 83(1), 365–418. https://doi.org/10.2138/rmg.2017.83.12

Farina, F., Dini, A., Davies, J. H. F. L., Ovtcharova, M., Greber, N. D., Bouvier, A.-S., et al. (2018). Zircon petrochronology reveals the timescale and mechanism of anatectic magma formation. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 495, 213–223.

Gardien, V., Reusser, E., & Marquer, D. (1994). Pre-Alpine metamorphic evolution of the gneisses from the Volpelline series (Western Alps, Italy). Schweizerische Mineralogische und Petrographische Mittelungen, 74, 489–502.

Garfagnoli, F., Menna, F., Pandeli, E., & Principi, G. (2009). Alpine metamorphic and tectonic evolution of the Inzecca-Ghisoni area (southern Alpine Corsica, France). Geological Journal, 44, 191–210.

Giuntoli, F., Lanari, P., Burn, M., Eva Kunz, B., & Engi, M. (2018). Deeply subducted continental fragments—Part 2: Insight from petrochronology in the central Sesia Zone (western Italian Alps). Solid Earth, 9, 191–222.

Giuntoli, F., Lanari, P., & Engi, M. (2018). Deeply subducted continental fragments—Part 1: Fracturing, dissolution–precipitation, and diffusion processes recorded by garnet textures of the central Sesia Zone (western Italian Alps). Solid Earth, 9(1), 167–189. https://doi.org/10.5194/se-9-167-2018

Goswami-Banerjee, S., & Robyr, M. (2015). Pressure and temperature conditions for crystallization of metamorphic allanite and monazite in metapelites: A case study from the Miyar Valley (high Himalayan Crystalline of Zanskar, NW India). Journal of Metamorphic Geology, 33, 535–556.

Gregory, C. J., Rubatto, D., Allen, C. M., Williams, I. S., Hermann, J., & Ireland, T. (2007). Allanite micro-geochronology: A LA-ICP-MS and SHRIMP U–Th–Pb study. Chemical Geology, 15, 162–182.

Gregory, C. J., Rubatto, D., Hermann, J., Berger, A., & Engi, M. (2012). Allanite behaviour during incipient melting in the southern Central Alps. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 84, 433–458.

Guillong, M., Meier, D. L., Allan, M. M., Heinrich, C. A., & Yardley, B. W. D. (2008). Sills: A Matlab-based program for the reduction of laser ablation ICP-MS data of homogeneous materials and inclusions. Mineralogical Association of Canada Short Course, 40, 328–333.

Hentschel, F., Janots, E., Trepmann, C. A., Magnin, V. & Lanari, P. (2020). Coronas around monazite and xenotime recording incomplete replacement reactions and compositional gradients during greenschist facies metamorphism and deformation. European Journal of Mineralogy, 32, 521–544.

Hermann, J., & Müntener, O. (1996). Extension-related structures in the Malenco-Margna system: Implications for the paleogeography and consequences for rifting and Alpine tectonics. Schweizerische Mineralogische und Petrographische Mittelungen, 76, 501–519.

Hermann, J., & Rubatto, D. (2003). Relating zircon and monazite domains to garnet growth zones: Age and duration of grnulite facies metamorphism in the Val Malenco lower crust. Journal of Metamorphic Geology, 21, 833–852.

Jackson, S. (2008). LAMTRACE data reduction software for LA-ICP-MS. Mineralogical Association of Canada Short Course Series. In P. Sylvester (Ed.), Laser ablation-ICP-mass spectrometry in the Earth sciences: Current practices and outstanding issues (Vol. 40, pp. 305–307). Québec: Mineralogical Association of Canada.

Janots, E., Engi, M., Rubatto, D., Berger, A., & Gregory, C. (2009). Metamorphic rates in collisional orogeny from in situ allanite and monazite dating. Geology, 37, 11–14. https://doi.org/10.1130/G25192A.1

Janots, E., Negro, F., Brunet, F., Goffé, B., Engi, M., & Bouybaouene, M. L. (2006). Evolution of the REE mineralogy in HP-LT metapelites of the Sebtide complex, Rif, Morocco: Monazite stability and geochronology. Lithos, 87, 214–234.

Janots, E., & Rubatto, D. (2014). U–Th–Pb dating of collision in the external Alpine domains (Urseren zone, Switzerland) using low temperature allanite and monazite. Lithos, 184–187, 155–166.

Jochum, K. P., Nohl, U., Herwig, K., Lammel, E., Stoll, B., & Hofmann, A. W. (2005). GeoReM: A new geochemical database for reference materials and isotopic standards. Geostandards and Geoanalytical Research, 29, 333–338.

Jochum, K. P., Weis, U., Stoll, B., Kuzmin, D., Yang, Q., Raczek, I., et al. (2011). Determination of reference values for NIST SRM 610–617 glasses following ISO guidelines. Geostandards and Geoanalytical Research, 35, 397–429.

Kunz, B. E., Manzotti, P., von Niederhäusern, B., Engi, M., Darling, J. R., Giuntoli, F., & Lanari, P. (2018). Permian high-temperature metamorphism in the Western Alps (NW Italy). International Journal of Earth Science, 107(1), 203–229. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00531-017-1485-6

Lacombe, O., & Jolivet, L. (2005). Structural and kinematic relationships between Corsica and the Pyreneeses-Provence domain at the time of the Pyrenean orogeny. Tectonics, 24, TC1003. https://doi.org/10.1029/2004TC001673

Langone, A., José, A. P. N., Ji, W. Q., Zanetti, A., Mazzucchelli, M., Tiepolo, M., et al. (2017). Ductile–brittle deformation effects on crystal-chemistry and U–Pb ages of magmatic and metasomatic zircons from a dyke of the Finero Mafic Complex (Ivrea–Verbano Zone, Italian Alps). Lithos, 284, 493–511.

Lardeaux, J. M., & Spalla, M. I. (1991). From granulites to eclogites in the Sesia Zone (Italian Western Alps)—A record of the opening and closure of the Piedmont ocean. Journal of Metamorphic Geology, 9(1), 35–59.

Lavier, L., & Manatschal, G. (2006). A mechanism to thin the continental lithosphere at magma-poor margins. Nature, 440, 324–328.

Liberi, F., Piluso, E., & Langone, A. (2011). Permo-Triassic thermal events in the lower Variscan continental crust section of the Northern Calabrian Arc, Southern Italy: Insights from petrological data and in situ U–Pb geochronology on gabbros. Lithos, 124, 291–307.

Maggi, M., Rossetti, F., Corfu, F., Theye, T., Andersen, T. B., & Faccenna, C. (2012). Clinopyroxene-rutile phyllonites from East Tenda Shear Zone (Alpine Corsica, France): Pressure-temperature-time constraints to the Alpine reworking of Variscan Corsica. Journal of the Geological Society of London, 169, 723–732.

Malasoma, A., & Marroni, M. (2007). HP/LT metamorphism in the Volparone Breccia (Northern Corsica, France): Evidence for involvement of the Europe/Corsica continental margin in the Alpine subduction zone. Journal of Metamorphic Geology, 25, 529–545.

Malavieille, J., Chemenda, A., & Larroque, C. (1998). Evolutionary model for the Alpine Corsica: Mechanism for ophiolite emplacement and exhumation of high-pressure rocks. Terra Nova, 10, 317–322.

Manatschal, G., & Müntener, O. (2009). A type-sequence across an ancient magma-poor ocean-continent transition: The example of the western Alpine Tethys ophiolites. Tectonophysics, 473(1–2), 4–19.

Manzotti, P., Ballèvre, M., & Dal Piaz, G. V. (2017). Continental gabbros in the Dent Blanche Tectonic System (Western Alps): From the pre-Alpine crustal structure of the Adriatic palaeo-margin to the geometry of an alleged subduction interface. Journal of the Geological Society London, 174, 541–556. https://doi.org/10.1144/jgs2016-071

Manzotti, P., Rubatto, D., Darling, J., Zucali, M., Cenki-Tok, B., & Engi, M. (2012). From Permo-Triassic lithospheric thinning to Jurassic rifting at the Adriatic margin: Petrological and geochronological record in Valtournenche (Western Italian Alps). Lithos, 146–147, 276–292.

Manzotti, P., Rubatto, D., Zucali, M., El Korh, A., Cenki-Tok, B., Ballèvre, M., & Engi, M. (2018). Permian magmatism and metamorphism in the Dent Blanche nappe: Constraints from field observations and geochronology. Swiss Journal of Geosciences, 111, 79–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00015-017-0284-1

Marotta, A. M., & Spalla, M. I. (2007). Permian-Triassic high thermal regime in the Alps: Result of late Variscan collapse or continental rifting? Validation by numerical modelling. Tectonics, 26, 1–27.

Marroni, M., Meneghini, F., & Pandolfi, L. (2017). A revised subduction inception model to explain the Late Cretaceous, double-vergent orogen in the pre-collisional western Tethys: Evidence from the Northern Apennines. Tectonics, 36, 2227–2249. https://doi.org/10.1002/2017TC004627

Marroni, M., Meneghini, F., Pandolfi, L., Hobbs, N., & Luvisi, E. (2019). The Ottone-Levanto Line of Eastern Liguria (Italy) uncovered: A Late Eocene-Early Oligocene snapshot of Northern Apennine geodynamics at the Alps/Apennines Junction. Episodes, 42(2), 107–118.

Marroni, M., & Pandolfi, L. (2003). Deformation history of the ophiolite sequence from the Balagne Nappe, northern Corsica: Insights in the tectonic evolution of the Alpine Corsica. Geological Journal, 38, 67–83.

Marroni, M., & Pandolfi, L. (2007). The architecture of an incipient oceanic basin: A tentative reconstruction of the Jurassic Liguria-Piemonte basin along the Northern Apennine-Alpine Corsica transect. International Journal of Earth Sciences, 96, 1059–1078.

Martin, A. J., Rubatto, D., Vitale Brovarone, A., & Hermann, J. (2011). Late Eocene lawsonite-eclogite facies metasomatism of a granulite sliver associated to ophiolites in Alpine Corsica. Lithos, 125, 620–640.

Mattauer, M., Faure, M., & Malavieille, J. (1981). Transverse lineation and large-scale structures related to Alpine obduction in Corsica. Journal of Structural Geology, 3(4), 401–409.

Ménot, R. P. (1990). Evolution du socle anté-Stéphanien de Corse. Schweizerische Mineralogische und Petrographische Mittelungen, 70, 35–54.

Meresse, F., Lagabrielle, Y., Malavieille, J., & Ildefonse, B. (2012). A fossil Ocean-Continent Transition of the Mesozoic Tethys preserved in the Schistes Lustrés nappe of northern Corsica. Tectonophysics, 579, 4–16.

Mohn, G., Manatschal, G., Beltrando, M., Masini, E., & Kusznir, N. (2012). Necking of the continental crust in magma-poor rifted margins: Evidence from the fossil Alpine Tethys margins. Tectonics, 31, TC1012. https://doi.org/10.1029/2011TC002961

Mohn, G., Manatschal, G., Masini, E., & Muntener, O. (2011). Rift-related inheritance in orogens: A case study from the Austroalpine nappes in Central Alps (SE-Switzerlan and N-Italy). International Journal of Earth Sciences (Geologische Rundschau), 100, 937–961.

Molli, G. (2008). Northern Apennine-Corsica orogenic system: an updated overview. In S. Siegesmund, B. Fugenschuh, & N. Froitzheim (Eds.), Tectonic aspects of the Alpine–Dinaride–Carpathian system (Vol. 298, pp. 413–442). London: Geological Society Special Publications.

Molli, G., & Malavieille, J. (2011). Orogenic processes and the Corsica/Apennines geodynamic evolution: Insights from Taiwan. International Journal of Earth Sciences, 100, 1207–1224.

Molli, G., Menegon, L., & Malasoma, A. (2017). Switching deformation mode and mechanisms during subduction of continental crust: A case study from Alpine Corsica. Solid Earth Discussions. https://doi.org/10.5194/se-2017-11

Molli, G., Tribuzio, R., & Marquer, D. (2006). Deformation and metamorphism at the eastern border of Tenda Massif (NE Corsica): A record of subduction and exhumation of continental crust. Journal of Structural Geology, 28, 1748–1766.

Müntener, O., & Hermann, J. (2001). The role of lower crust and continental upper mantle during formation of non-volcanic passive margins: Evidence from the Alps. Geological Society London Special Publications, 187, 267–288.

Oberli, F., Meier, M., Berger, A., Rosemberg, C. L., & Gieré, R. (2004). U–Th–Pb and 230Th–238U disequilibrium isotope systematics: Precise accessoru mineral chronology and melt evolution tracing in the Alpine Bergell intrusion. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 68, 2543–2560.

Ohnenstetter, M., & Rossi, P. (1985). Découverte d’une paléochambre magmatique exceptionelle dans le massif du Tenda, Corse hercynienne. Comptes Rendus de l’Académie des Sciences Paris, 300, 853–858.

Pandolfi, L., Marroni, M., & Malasoma, A. (2016). Stratigraphic and structural features of the Bas-Ostriconi Unit (Corsica): Paleogeographic implications. Comptes Rendus Geoscience, 348, 630–640.

Paquette, J. L., Chopin, C., & Peucat, J. J. (1989). U–Pb zircon, Rb–Sr and Sm–Nd geochronology of high-to very-high pressure metaacidic rocks from the Western Alps. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 101, 280–289.

Paquette, J. L., Ménot, R. P., Pin, C., & Orsini, J. B. (2003). Episodic and short-lived granitic pulses in a post-collisional setting: Evidence from precise U–Pb zircon dating through a crustal cross-section in Corsica. Chemical Geolology, 198, 1–20.

Peressini, G., Quick, J. E., Sinigoi, S., Hofmann, A. W., & Fanning, M. (2007). Duration of a large mafic intrusion and heat transfer in the lower crust: A SHRIMP U–Pb zircon study in the Ivrea-Verbano Zone (Western Alps, Italy). Journal of Petrology, 48(6), 1185–1218.

Péron-Pinvidic, G., & Manatschal, G. (2009). The final rifting evolution at deep magma-poor passive margins from Iberia-Newfoundland: A new point of view. International Journal of Earth Sciences, 98, 1581–1597.

Pettke, T., Oberli, F., Audétat, A., Guillong, M., Simon, A. C., Hanley, J. J., & Klemm, L. M. (2011). Recent developments in element concentration and isotope ratio analysis of individual fluid inclusions by laser ablation single and multiple collector ICP–MS. Ore Geology Reviews, 44, 10–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oregeorev.2011.11.001

Pidgeon, R. T. (1992). Recrystallisation of oscillatory zoned zircon: Some geochronological and petrological implications. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 110, 463–472.

Quick, J., Sinigoi, S., Negrini, L., Demarchi, G., & Mayer, A. (1992). Synmagmatic deformation in the underplated igneous complex of the Ivrea-Verbano Zone, northern Italy. Geology, 20, 1–2776.

Regis, D., Rubatto, D., Darling, J., Cenki-Tok, B., Zucali, M., & Engi, M. (2014). Multiple metamorphic stages within an eclogite-facies terrane (Sesia Zone, Western Alps) revealed by Th–U–Pb petrochronology. Journal of Petrology, 55, 1429–1456.

Renna, M. R., Tribuzio, R., & Tiepolo, M. (2007). Origin and timing of the post-Variscan gabbro-granite complex of Porto (Western Corsica). Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 154, 493–517.

Ribes, C., Manatschal, G., Ghienne, J.-F., Karner, G. D., Johnsonm, C. A., Flgueredo, P. H., et al. (2019). The syn-rift stratigraphic recrord across a fossil hyper-extended rifted margin: The example of the northwestern Adriatic margin exposed in the Central Alps. International Journal of Earth Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00531-019-01750-6

Roda, M., & Zucali, M. (2008). Meso and microstructural evolution of the Mont Marion metaintrusive complex (Dent Blanche nappe, Austroalpine domain, Valpelline, Western Italian Alps). Italian Journal of Geoscience, 127, 105–123.

Rossetti, F., Glodny, J., Theye, T., & Maggi, M. (2015). Pressure temperature deformation-time of the ductile Alpine shearing in Corsica from orogenic construction to collapse. Lithos, 218–219, 99–116.

Rossi, P., Cocherie, A., & Fanning, M. (2015). Evidence in Variscan Corsica of a brief and voluminous Late Carboniferous to Early Permian volcanic-plutonic event contemporaneous with a high-temperature/low-pressure metamorphic peak in the lower crust. Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France, 186(2–3), 171–192.

Rubatto, D., Regis, D., Hermann, J., Boston, K., Engi, M., Beltrando, M., & McAlpine, S. (2011). Yo-Yo subduction recorded by accessory minerals (Sesia Zone, Western Alps). Nature Geosciences, 4, 338–342. https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo1124

Samperton, K. M., Schoene, B., Cottle, J. M., Keller, C. B., Crowley, J. L., & Schmitz, M. D. (2015). Magma emplacement, differentiation and cooling in the middle crust: Integrated zircon geochronological-geochemical constraints from the Bergell Intrusion, Central Alps. Chemical Geology, 417, 322–340.

Santamaría-López, Á., Lanari, P., & Sanz de Galdeano, C. (2019). Deciphering the tectono-metamorphic evolution of the Nevado-Filábride complex (Betic Cordillera, Spain)—A petrochronological study. Tectonophysics, 767, 128158.

Schaltegger, U., & Brack, P. (2007). Crustal scale magmatism systems during intracontinental strike-slip tectonics: U, Pb and Hf isotopic constraints for Permian magmatic rocks of the Southern Alps. International Journal of Earth Sciences, 96, 1131–1151.

Schaltegger, U., Ulianov, A., Müntener, O., Ovtcharova, M., Vonlanthen, P., Vennemann, T., et al. (2015). Megacrystic zircon with planar fractures in miaskite-type nepheline pegmatites formed at high pressures in the lower crust (Ivrea Zone, Southern Alps, Switzerland). American Mineralogist, 100, 83–94. https://doi.org/10.2138/am-2015-4773

Schuster, R., & Stüwe, K. (2008). Permian metamorphic event in the Alps. Geology, 36, 603–606.

Seymour, N. M., Stockli, D. F., Beltrando, M., & Smye, A. J. (2016). Tracing the thermal evolution of the Corsican lower crust during Tethyan rifting. Tectonics, 35, 2439–2466. https://doi.org/10.1002/2016TC004178

Sláma, J., Košler, J., Condon, D. J., Crowley, J. L., Gerdes, A., Hanchar, J. M., et al. (2008). Plešovice zircon—A new natural reference material for U–Pb and Hf isotopic microanalysis. Chemical Geology, 249, 1–35.

Smith, H. A., & Barreiro, B. (1990). Monazite U–Pb dating of staurolite grade metamorphism in pelitic schists. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 105, 602–615.

Spencer, C. J., Kirkland, C. L., & Taylor, R. J. M. (2016). Strategies towards statistically robust interpretations of in situ U–Pb zircon geochronology. Geoscience Frontiers, 7(4), 581–589.

Stacey, J. S., & Kramers, J. D. (1975). Approximation of terrestrial lead isotope evolution by a 2-stage model. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 26(2), 207–221.

Tedeschi, M., Pedrosa-Soares, A., Dussin, I., Lanari, P., Novo, T., Pinheiro, M. A. P., et al. (2018). Protracted zircon geochronological record of UHT garnet-free granulites in the Southern Brasília orogen (SE Brazil): Petrochronological constraints on magmatism and metamorphism. Precambrian Research, 316, 103–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.precamres.2018.07.023

Thöni, M., & Miller, C. (2009). The “Permian event” in the Eastern European Alps: Sm–Nd and P–T data recorded by multi-stage garnet from the Plankogel unit. Chemical Geology, 260, 20–36.

Tomkins, H. S., & Pattinson, D. R. M. (2007). Accessory phase petrogenesis in relation to major phase assemblages in pelites from Nelson contact aureole, Southern British Columbia. Journal of Metamorphic Geology, 25, 401–421.

Tribuzio, R., Renna, M. R., Braga, R., & Dallai, L. (2009). Petrogenesis of Early Permian olivine-bearing cumulate and associated basalt dykes from Bocca di Tenda (Northern Corsica): Implications for post-collisional Variscan evolution. Chemical Geology, 259, 190–203.

Tribuzio, R., Thirlwall, M. F., & Messiga, B. (1999). Petrology, mineral and isotope geochemistry of the Sondalo gabbroic complex (Central Alps, Northern Italy): Implications for the origin of post-Variscan magmatism. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 136, 48–62.

Trommsdorff, V., Piccardo, G. B., & Montrasio, A. (1993). From magmatism through metamorphism to sea floor emplacement of subcontinental Adria lithosphere during pre-Alpine rifting (Malenco, Italy). Schweizerische Mineralogische und Petrographische Mittelungen, 73, 191–203.

Ulianov, A., Müntener, O., Schaltegger, U., & Bussy, F. (2012). The data treatment dipendent variability of U–Pb zircon ages obtained using mono-collector, sector field, laser ablation, ICPMS. Journal of Analytical Atomic Spectrometry, 27(4), 663–676.

Vavra, G., Gebauer, D., Schmidm, R., & Comptson, W. (1996). Multiple zircon growth and recrystallization during polyphase Late Carboniferous to Triassic metamorphism in granulites of Ivrea zone (southern Alps): An ion microprobe (SCHRIMP) study. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 122, 337–358.

Vho, A., Rubatto, D., Lanari, P. & Regis, D. (2020). The evolution of the Sesia Zone (Western Alps) from Carboniferous to Cretaceous: Insights from zircon and allanite geochronology. Swiss Journal of Geosciences. https://doi.org/10.1186/s00015-020-00372-4.

Vitale Brovarone, A., Beltrando, M., Malavieille, J., Giuntoli, F., Tondella, E., Groppo, C., et al. (2011). Inherited Ocean–Continent transition zones in deeply subducted terranes: Insights from Alpine Corsica. Lithos, 124, 273–290.

Vitale Brovarone, A., Picatto, M., Beyssac, O., Lagabrielle, Y., & Castelli, D. (2014). The blueschist-eclogite transition in the Alpine chain: P–T paths and the role of slow-spreading extensional structures in the evolution of HP-LT mountain belts. Tectonophysics, 615, 96–121.

von Blanckenburg, F. (1992). Combined high-precision chronometry and geochemical tracing using accessory minerals: Applied to the Central-Alpine Bergell intrusion (central Europe). Chemical Geology, 100, 19–40.

Whitney, D., & Evans, B. (2010). Abbreviations for names of rock-forming minerals. American Mineralogist, 95, 185–187. https://doi.org/10.2138/am.2010.3371

Winterer, E. J., & Bosellini, A. (1981). Subsidence and sedimentation on Jurassic passive continental margin, Southern Alps. Italy. American Association of Petroleum Geologists Bulletin, 65, 394–421.

Zanetti, A., Giovanardi, T., Langone, A., Tiepolo, M., Wu, F. Y., Dallai, L., & Mazzucchelli, M. (2016). Origin and age of zircon-bearing chromitite layers from the Finero phlogopite peridotite (Ivrea–Verbano Zone, Western Alps) and geodynamic consequences. Lithos, 262, 58–74.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge Andrea Dini for his help with the zircon separation and Alexey Ulianov for the laboratory assistance. We thank Daniele Regis and an anonymous reviewer for their constructive comments that helped to improve the clarity of the original manuscript and the Editor Paola Manzotti for her detailed and constructive comments.

Funding

This work was supported by the “Il Pianeta Dinamico: sviluppi e prospettive a 100 anni da Wegener” grant provided by AIV-SGI-SIMP-SOGEI societies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MDR did the field works, sampling surveys, separated the zircon grains, assisted to the laboratory analyses, processed the data and wrote the text. FF performed the zircon analysis and collaborated with the data processes. PL performed the allanite analysis and processed the related data. MM assisted the sampling, interpreted the data together with MDR and wrote part of the discussion. FF and PL helped in the writing of the methods and results sections and provided useful comments to the other sections of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Editorial Handling: Paola Manzotti.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1:

Allanite data.

Additional file 2:

Additional analyzed zircons.

Additional file 3:

Decision tree for the classification model.

Rights and permissions