Abstract

Background

Hemangioma is a well-known neoplasia in veterinary and human medicine. Several subtypes have been described and are distinguished based on their histologic appearance. The classification schemes of hemangiomas in human and veterinary medicine are different, and various purpose-based schemes can be found in the literature.

Case presentation

A six-week-old puppy was presented that suffered from a neoplasia that extended to the musculature of the hind limb. After surgical excision, the mass was submitted for pathohistological examination. The mass was composed of endothelial cells forming vascular slits admixed with a fibrous stroma and spindle cells. Immunohistological examination was positive for factor VIII-related antigen and smooth muscle actin, supporting the diagnosis of hemangioma.

Conclusion

The final diagnosis of granulation tissue-type hemangioma was given due to the histological appearance of the neoplasia. Granulation tissue-type hemangioma is a rare subtype of hemangioma. In this case an uncommonly young dog was affected.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Vascular tumors are common neoplasms in dogs. Approximately half of all canine vascular tumors occur in the skin, and most of them are benign neoplasms or tumor-like lesions (e.g., vascular malformations) [1]. Hemangiomas are benign tumors of the blood vessels and are a common and well-known lesion in veterinary medicine, especially in dogs, where they account for about 3.8 to 4.5% of all skin tumors [2, 3]. They usually occur in older dogs more than 10 years of age and are uncommon below 3 years of age [4]. In contrast, vascular tumors are more common in horses and calves at a young age [5,6,7]. In young animals, it is often difficult to distinguish between a benign neoplasm and a vascular malformation (nevus or hamartoma). Apart from UV-induced hemangiomas, the etiology of canine hemangiomas is unknown [3]. There is a suggested breed-specific predisposition in several breeds, such as American Staffordshire Terrier, Beagles and Dalmatians but they are common in light-skinned dogs and are related to UV-induced hemangiomas [3, 4, 8]. Granulation tissue-type hemangiomas (GTH) are rarely described in veterinary medicine. Because the veterinary literature on this subtype is sparse, sex predilection or predilected anatomical sites are unknown.

Case presentation

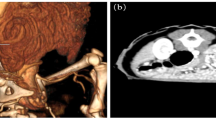

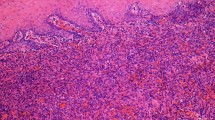

A six-week-old female Hanoverian Scenthound was presented because of a 3 × 4 × 1 cm subcutaneous neoplasm on the left lateral hind limb that was associated with the musculature (Fig. 1A). The regional lymph node (Ln. popliteus) was not affected. At 2 weeks of age, all puppies had been affected by pyoderma. The puppy was initially treated with Traumeel® (Biologische Heilmittel Heel GmbH, Germany). Two days later, the puppy was presented again as no changes occurred. Pulsation was palpable, and sonography showed an inhomogeneous structure rich in blood vessels. Four weeks after the initial presentation, the mass had grown to 7 × 6 × 1.5 cm and had invaded the surrounding tissue. There was no demarcation to the gastrocnemius muscle and flexor digitalis superficialis muscle and a strong blood supply. The mass and regional lymph node were surgically removed at the owner’s decision. Four days after initial treatment, surgical revision and renewal of vessel ligation were performed due to severe postoperative bleeding in the wound area. Subsequently, wound healing proceeded without complications. At the time of writing (5 months postoperatively) the animal displays no evidence of recurrence and the puppy developed physiologically without loss of performance or physical limitations. The mass and lymph node were sent for histopathologic examination. The samples were processed routinely, and sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin stain. Immunohistochemistry was performed to detect factor VIII-related antigen (rabbit anti-factor VIII PAP polyclonal, Agilent Technologies®, Waldbronn, Germany; formerly DAKO® Hamburg, Germany), alpha-smooth muscle actin (αSMA; mouse anti-alpha-smooth-muscle-actin ABC monoclonal Agilent Technologies®, Waldbronn, Germany), vimentin (mouse anti-vimentin ABC monoclonal, Agilent Technologies®, Waldbronn, Germany), desmin (mouse anti-desmin ABC monoclonal, Agilent Technologies®, Waldbronn, Germany), pan-cytokeratin (mouse anti-cytokeratin pan ABC monoclonal, OriGene Europe®, Herford, Germany) and melan A (mouse anti-melan A monoclonal, Santa Cruz Biotechnology®, Heidelberg, Germany). Biotinylated horse anti-mouse antibody (Vector Laboratories®, Eching, Germany) and biotinylated pig anti-rabbit antibody (Agilent Technologies®, Waldbronn, Germany) were used as secondary antibodies. Histopathology revealed a multinodular, unencapsulated, well-demarcated, partly infiltrative, moderately cellular subcutaneous mass that replaced subcutaneous adipose tissue and skeletal muscle (Fig. 1B). The mass consisted of streams and bundles of two populations of cells. One population of plump endothelial cells with a moderate amount of basophilic cytoplasm and a round to oval nucleus with finely stippled chromatin (Fig. 2A, B) formed slit-shaped vascular channels. The second population consisted of spindle cells with a moderate amount of pale basophilic cytoplasm and oval nuclei with mostly one nucleolus and coarsely clumped chromatin. The spindle cells and a fibrous stroma surrounded the slit vascular channels, occasionally with spindle cells arranged in circular manner around these channels, forming vascular structures (Fig. 2A, B). In some areas, the neoplasm consisted only of spindle cells on a fibrous stroma; in others, the spindle cell population was intermingled with the vascular structures or mostly consisted of vascular structures. There was moderate anisocytosis and anisokaryosis. Mitoses were rare in both populations (< 1 mitosis per high power field (HPF) [0,273 cm2]). The tissue was infiltrated with small numbers of lymphocytes, macrophages, and plasma cells. Neutrophilic granulocytes were found in some vascular structures formed by the tumor (not shown). There was mild regeneration of the skeletal musculature. The endothelial cells were positive for factor VIII-related antigen (Fig. 2C), and a subset of the spindle cells, particularly those encircling slit-like vascular channels, were positive for smooth muscle actin (Fig. 2D, E). Both cell populations were positive for vimentin and negative for pan-cytokeratin, desmin and melan A. Follicular hyperplasia, blood resorption and mild sinus histiocytosis were found in the lymph node. The histologic and immunohistological pattern supports the diagnosis of hemangioma. Based on the histological appearance, the neoplasm was classified as a granulation tissue-type hemangioma.

A, B HE-stain: Split population of plump endothelial cells with a moderate amount of basophilic cytoplasm and a round to oval nucleus with finely stippled chromatin (arrows) build erythrocyte-filled channels (asterisk) as well as spindle cells with a moderate amount of pale basophilic cytoplasm and oval nuclei with mostly one nucleolus and coarsely clumped chromatin with a fibrous stroma surrounding the vascular structures (arrowheads); C Factor-VIII-related antigen: Positive signal of endothelial cells (arrows); D, E SMA: Mainly positive signal of spindle cells (arrowheads) and negative endothelial cells (arrows)

Discussion and conclusions

In both human and veterinary medicine, several different classifications lead to confusion in the accurate diagnosis of vascular lesions. In particular, the distinction between hemangiomas (benign neoplasms of the vascular system that often occur in elderly patients) and vascular malformations (usually visible in infancy) is fluid, and the subclassification of these tumors is often vague and not clearly defined. The current International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies (ISSVA) classification of benign vascular tumors in humans distinguishes infantile hemangioma, congenital hemangioma, tufted angioma, spindle-cell hemangioma, epithelioid hemangioma, and pyogenic granuloma, in addition to some other subtypes that differ in appearance, incidence and prognosis [9]. Infantile hemangiomas in particular have been described to regress spontaneously in 50% of cases by 5 years of age, whereas pyogenic granulomas require treatment up to major, more invasive surgical excision [10, 11]. Spontaneous regression of congenital hemangiomas has also been described in calves [12]. In veterinary medicine, hemangiomas are usually divided primarily into two subtypes: cavernous hemangiomas and capillary hemangiomas [13]. Cavernous hemangioma is the most common type in dogs [1, 14]. Following human medicine, a much more precise classification and evaluation of the tumor is possible: in addition to the above subtypes, a distinction can be made between angiokeratomas, infiltrative growing, arteriovenous, spindle-cell, UV-induced, and granulation tissue-type hemangioma [3]. However, this classification is rarely used in the literature, making a more accurate assessment of prognosis and incidence difficult. According to the above classification, the diagnosis of GTH (also known as lobular capillary granuloma or pyogenic granuloma) can be made based on the histologic and immunohistological picture. GTH is characterized by the formation of capillary-like vessels, sometimes also larger vessels, separated by a fibrous stroma. It is distinguished from granulation tissue by the chaotic arrangement of the vessels and the overall appearance of a neoplasm [3]. The differential diagnoses for this case, based on histopathology and immunohistochemistry, are listed in Table 1. Myofibroblastic tumors are an important and tricky differential diagnosis, especially considering the number of SMA-positive cells between the slit-like vascular channels in the case presented here. The diagnosis is also complicated by the fact that myofibroblasts are an important component of wound healing and may be present in variable numbers in the granulation tissue depending on the maturation rate [15]. The literature on GTH and myofibroblastic tumors contains different definitions and similar features shared by both tumors, making a definitive diagnosis difficult [16,17,18]. Furthermore, both tumors are described as highly variable in their histologic appearance, and there are only few descriptions in veterinary medicine. Myofibroblastic tumors in animals have mostly been found in the body cavities [18]. Based on gross localization in the skin and the high vascular content confirmed histopathologically, we prefer the diagnosis of GTH. Features of GTH described in the literature are consistent with the histologic picture in this case, and the results of immunohistological examination further support the diagnosis of hemangioma. In human medicine, this subtype is known to be a rare benign vascular tumor mostly located in the skin of the head, the neck or in the oral cavity [19]. In contrast to human medicine, where clustering of hemangiomas is observed in females (with a presumption of a hormonal cause), there is no known sex predilection or predilected locations in dogs [4, 20]. An older study of 208 dogs with vascular tumors found an average of 61% females, suggesting clustering in females and possibly hormonal involvement as in humans [4]. In a study of 126 hemangiomas in dogs, granulation tissue-type hemangioma was found in approximately 10.3%, with no further information on sex or age [21]. Although pyogenic granuloma is classified as a subtype of hemangioma in human medicine, it is often referred to as a vascular malformation rather than a tumor. It frequently occurs in pregnant women, and in addition to a hormonal cause, injury often underlies it [11, 22]. Some human medical studies suggest an association between pyogenic granuloma and Bartonella infection, whereas in veterinary and human medicine cutaneous Bartonellosis is associated with bacillary angiomatosis [23,24,25]. The presented case is an unusual case of granulation tissue-type hemangioma in a young puppy. In contrast to granulation tissue-type hemangioma in humans this case occurred on the caudal portion of the dog’s body. In dogs, capillary hemangioma also commonly occurs on the dorsal aspect of the limbs but is distinguished from granulation tissue-type hemangioma based on their growth pattern [1]. Most cases of hemangiomas in young children are infantile or congenital hemangiomas. In addition, pyogenic granulomas usually occur in young (pregnant) women, suggesting that hormonal involvement may also be present in dogs. Congenital trauma as a cause cannot be excluded in this case, and a hormonal cause is rather unlikely because of age. In addition, a correlation between the neoplasm and the history of pyoderma in the puppies a few weeks earlier cannot be ruled out. In conclusion, despite the frequency of hemangiomas in dogs, granulation tissue-type hemangioma is a rare subtype that must be kept in mind as a differential diagnosis, especially considering the different classification schemes. Unlike infantile hemangiomas in humans and congenital hemangiomas in humans and cattle, there is no data on possible regression in dogs, so surgical excision should always be favored. A more precise definition of the different subtypes, also in regard to the clinical course, would improve the classification and facilitate the diagnosis. Although all tumors mentioned are considered benign, some subtypes of myofibroblastic tumors with more invasive growth and recurrence have been described in human medicine. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first published case of granulation tissue-type hemangioma in a young puppy.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- GTH:

-

Granulation tissue-type hemangioma

- IMT:

-

Myofibroblast Inflammatory tumor

- IPT:

-

Inflammatory Pseudotumor

- HE-stain:

-

Hematoxylin and eosin-stain

- SMA:

-

alpha-smooth-muscle-actin

References

Gamlem H, Nordstoga K, Arnesen K. Canine vascular neoplasia--a population-based clinicopathologic study of 439 tumours and tumour-like lesions in 420 dogs. APMIS Suppl. 2008;125:41–54.

Frese K, Durchfeld B, Eskens U. Klassifikation und biologisches Verhalten der Haut-und Mammatumoren von Hund und Katze. Prakt Tierärtz. 1989;9:69–84.

Gross TL, Ihrke PJ, Walder EJ, Affolter VK. Skin diseases of the dog and cat: clinical and histopathologic diagnosis. 2nd ed: Hong Kong John Wiley & Sons; 2008.

Hargis AM, Ihrke PJ, Spangler WL, Stannard AA. A retrospective clinicopathologic study of 212 dogs with cutaneous hemangiomas and hemangiosarcomas. Vet Pathol. 1992;29:316–28.

Yeruham I, Perl S, Orgad U. Congenital skin neoplasia in cattle. Vet Dermatol. 1999;10:149–56.

Misdorp W. Congenital tumours and tumour-like lesions in domestic animals. 1. Cattle a review. Vet Q. 2002;24:1–11.

Johnson GC, Miller MA, Floss JL, Turk JR. Histologic and Immunohistochemical characterization of Hemangiomas in the skin of seven young horses. Vet Pathol. 1996;33:142–9.

Nikula KJ, Benjamin SA, Angleton GM, Saunders WJ, Lee AC. Ultraviolet radiation, solar dermatosis, and cutaneous neoplasia in beagle dogs. Radiat Res. 1992 Jan;129:11–8.

International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies. ISSVA Classification of Vascular Anomalies 2018. Available from: https://www.issva.org/classification; Accessed: 26 Jul 2022.

Donnelly LF, Adams DM, Bisset GS III. Vascular malformations and hemangiomas: a practical approach in a multidisciplinary clinic. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;174:597–608.

Jafarzadeh H, Sanatkhani M, Mohtasham N. Oral pyogenic granuloma: a review. J Oral Sci. 2006;48:167–75.

Priestnall SL, De Bellis F, Bond R, Alony-Gilboa Y, Summers BA. Spontaneous regression of congenital cutaneous hemangiomas in a calf. Vet Pathol. 2010;47:343–5.

Hendrick MJ. Histological Classification of Mesenchymal Tumors of Skin and Soft Tissues of Domestic Animals. 2nd ed: Washington DC Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 1998.

Sabattini S, Bettini G. An immunohistochemical analysis of canine haemangioma and haemangiosarcoma. J Comp Pathol. 2009;140:158–68.

Desmoulière A. Factors influencing myofibroblast differentiation during wound healing and fibrosis. Cell Biol Int. 1995;19:471–6.

Palaskar S, Koshti S, Maralingannavar M, Bartake A. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor. Contemp Clin. Dent. 2011;2:274–7.

Carrasco Rodríguez R, García Fontán EM, Blanco Ramos M, Magdalena Benavides LJ, Otero Lozano D, Moldes RM. Inflammatory pseudotumor and myofibroblastic inflammatory tumor. Diagnostic criteria and prognostic differences. Cir Esp. 2022;100:329–35.

Knight C, Fan E, Riis R, McDonough S. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors in two dogs. Vet Pathol. 2009;46:273–6.

Murthy J. Vascular anomalies. Indian J Plst Surg. 2005;38:56–62.

Yuan K, Wing LY, Lin MT. Pathogenetic roles of angiogenic factors in pyogenic granulomas in pregnancy are modulated by female sex hormones. J Periodontol. 2002;73:701–8.

Gamlem H, Nordstoga K. Canine vascular neoplasia--histologic classification and immunohistochemical analysis of 221 tumours and tumour-like lesions. APMIS Suppl. 2008;2008:19–40.

Gondivkar SM, Gadbail A, Chole R. Oral pregnancy tumor. Contemp Clin. Dent. 2010;1:190–2.

Yager JA, Best SJ, Maggi RG, Varanat M, Znajda N, Breitschwerdt EB. Bacillary angiomatosis in an immunosuppressed dog. Vet Dermatol. 2010;21:420–8.

Lee J, Lynde C. Pyogenic granuloma: pyogenic again? Association between pyogenic granuloma and Bartonella. J Cutan Med Surg. 2001;5:467–70.

Levy I, Rolain J-M, Lepidi H, Raoult D, Feinmesser M, Lapidoth M, et al. Is pyogenic granuloma associated with Bartonella infection? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:1065–6.

Kawachi N. A comparative Histopathological and Immunohistochemically study of capillary Hemangioma, pyogenic granuloma and cavernous Hemangioma in the Oral region: with special reference to vascular proliferation factors. Int J Oral-Med Sci. 2011;9:241–51.

Epivatianos A, Antoniades D, Zaraboukas T, Zairi E, Poulopoulos A, Kiziridou A. Pyogenic granuloma of the oral cavity: comparative study of its clinicopathological and immunohistochemical features. Pathol Int. 2005;55:391–7.

Abramo F, Vascellari M, Colzi G, Pazzini L, Albanese F, Olivieri L. Identification of Histopathological criteria for the diagnosis of canine cutaneous progressive Angiomatosis. Vet Sci. 2022;9:340.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JM contributed to the interpretation of data and drafted the manuscript. SH contributed to the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data, drafted the manuscript in parts and critically revised the manuscript. MH contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data, and critically revised the manuscript. JHM contributed to the acquisition of the data and revised the manuscript. All authors gave final approval and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions relating to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

The authors confirmed that the owner had given verbal consent for their pet’s personal or clinical details to be published in this publication.

Competing interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest concerning the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Müller, J., Henrich, M., Hoogen-Merkel, J. et al. Granulation tissue-type hemangioma in a 6-week-old puppy – a case report. BMC Vet Res 18, 431 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-022-03503-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-022-03503-1