Abstract

Background

Patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) are highly at risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD). However, the risk of developing CVD in patients with lean NAFLD is not yet fully understood. Therefore, this study aimed to compare the CVD incidence in Japanese patients with lean NAFLD and those with non-lean NAFLD.

Methods

A total of 581 patients with NAFLD (219 with lean and 362 with non-lean NAFLD) were recruited. All patients underwent annual health checkups for at least 3 years, and CVD incidence was investigated during follow-up. The primary end-point was CVD incidence at 3 years.

Results

The 3-year new CVD incidence rates in patients with lean and non-lean NAFLD were 2.3% and 3.9%, respectively, and there was no significant difference between two groups (p = 0.3). Multivariable analysis adjusted for age, sex, hypertension, diabetes, and lean NAFLD/non-lean NAFLD revealed that age (every 10 years) as an independent factor associated with CVD incidence with an odds ratio (OR) of 2.0 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.3–3.4), whereas lean NAFLD was not associated with CVD incidence (OR: 0.6; 95% CI: 0.2–1.9).

Conclusions

CVD incidence was comparable between patients with lean NAFLD and those with non-lean NAFLD. Therefore, CVD prevention is needed even in patients with lean NAFLD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) currently occurs in > 25% of the world population and is one of the major health problems [1,2,3,4,5]. Patients with NAFLD have high risk for developing liver-related events including hepatocellular carcinoma and decompensation. Prevention and early detection of these complications are important clinical issue [6,7,8,9,10]. Because NAFLD is a disease associated with metabolic syndrome and is frequently complicated by diabetes and hyperlipidemia [11,12,13], patients with NAFLD are also highly at risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD) events [14, 15]. CVD has been known to more frequently occur in patients with NAFLD than in the general population [16]. Therefore, CVD prevention is an important issue that should be considered in patients with NAFLD [17,18,19,20]. Because NAFLD is strongly associated with metabolic syndrome, many patients with NAFLD are obese. However, some patients have lean NAFLD (defined as a BMI of < 25 kg/m2 in Western subjects and < 23 kg/m2 in Asian subjects) [21]. In addition, whether lean NAFLD is associated with disease progression, especially the risk of developing CVD, is not yet fully understood. Furthermore, the rate of lean NAFLD varies by race and region [22]. Therefore, even among patients with lean NAFLD, the risk of CVD may also differ by race and region, and the association between each of these factors and CVD risk remains to be verified. Therefore, this study aimed to examine whether CVD incidence differs between lean and non-lean NAFLD in Japanese patients.

Methods

Study protocol

This is a single-center, retrospective study of 5171 patients who underwent health checkup at Musashino Red Cross Hospital from January 2017 to May 2022. A total of 1351 patients with NAFLD were included, excluding 1178 with a history of alcohol consumption (defined as daily alcohol consumption of at least 30 g/day of ethanol for men and 20 g/day for women [23]), 2597 without fatty liver, and 45 with missing data. Patients underwent annual health checkups at least 3 years. After excluding 711 patients who did not reach a 3-year follow-up and 59 with a history of CVD, 581 patients were finally analyzed: 219 patients with lean NAFLD (BMI < 23 kg/m2) and 362 patients with non-lean NAFLD (BMI ≥ 23 kg/m2) (Fig. 1). This study was conducted following the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and with the consent of the ethics committee of the institution where the study was conducted (Approval Number: 1005). We obtained consent from all patients using an opt-out approach.

Clinical and laboratory data

Age, sex, weight, smoking history, alcohol intake, and blood test data were recorded on the date of the first medical checkup.

Definition of fatty liver

Ultrasonographic findings of parenchymal brightness, liver-to-kidney contrast, deep beam attenuation, and bright vessel walls were considered indicators of a fatty liver at the first medical checkup [24, 25].

Definition of comorbidity status

Diabetes mellitus was defined as a fasting plasma glucose level of ≥ 126 mg/dL, hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level of ≥ 6.5%, or use of any antihyperglycemic medication [26]. Dyslipidemia was defined as elevated triglycerides (≥ 150 mg/dL), elevated low-density lipoprotein (≥ 140 mg/dL), decreased high-density lipoprotein (< 40 mg/dL in men and < 50 mg/dL in women), or use of any lipid-lowering medication [27]. Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure of ≥ 140 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure of ≥ 90 mmHg, or use of any antihypertensive medication [28]. Significant alcohol consumption was defined as > 30 and > 20 g/week in men and women, respectively [23].

Diagnosis of CVD

CVD was defined as ischemic heart disease, heart failure, cerebrovascular disease, and peripheral arterial disease. Its incidence was investigated through interviews at the time of annual health checkups or from medical records.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was the occurrence of new cardiovascular events within 3 years, and the incidence of cardiovascular events in patients with lean and non-lean NAFLD was compared.

Statistical analysis

Patient backgrounds of lean and non-lean NAFLD were compared using Student’s t-test or Fisher’s exact test. Logistic analysis was used to compare factors associated with new CVD events over 3 years. The logistic analysis included the following factors: age, gender, diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia as well as lean or non-lean NAFLD. Of these metabolic associated factors (diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia), factors that were significant in univariate analysis were entered into the multivariate analysis. P-values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using EZR [29].

Results

Patient characteristics

The numbers of patients with lean and non-lean NAFLD were 219 and 362, respectively. The mean ± standard deviation values of the patients’ age were 58 ± 12 and 59 ± 11 years, respectively, without significant differences between the two groups (p = 0.8). A total of 110 (50.2%) and 220 (60.8%) males had lean and non-lean NAFLD, respectively (p = 0.02); 47 (21.5%) and 138 (38.1%) had hypertension (p < 0.01); and 20 (9.1%) and 57 (15.7%) had diabetes (p = 0.02). In the non-lean NAFLD group, rates of men, hypertension, and diabetes were significantly higher than the lean-NAFLD group. Dyslipidemia was observed in 108 (49.3%) and 201 (55.5%) (p = 0.2) and smoking history was observed in 23 (10.5%) and 44 (12.2%) patients (p = 0.6; Table 1) in the lean and non-lean NAFLD groups, respectively. The median (interquartile range) systolic and diastolic blood pressure of patients with hypertension was 128 (118–142) and was 81 (74–87] mmHg, respectively. HbA1c of patients with diabetes was 6.8 (6.5–7.2] % and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol of patients with dyslipidemia was 143 (110–158) mg/dL.

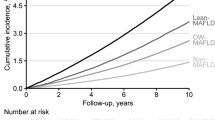

The percentage of new CVD incidence in 3 years

The 3-year incidence rates of new CVD in the lean and non-lean NAFLD groups were 2.3% and 3.9%, respectively, without a significant difference (p = 0.3, Fig. 2). In the lean NAFLD group, 5 of 219 patients developed CVD: 4 cerebral infarctions and 1 myocardial infarction. In the non-lean NAFLD group, 14 of 362 patients developed CVD: 4 cerebral infarctions, 2 transit ischemic attacks, 2 heart failure, 4 myocardial infarctions, and 2 peripheral artery diseases.

Factors of new CVD incidence in 3 years

Factors associated with the development of new CVD were examined. Multivariate analysis revealed that age (in every 10 years) (odds ratio [OR]: 2.0; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.3–3.4; p < 0.01) was an independent factor associated with the development of new CVD, whereas lean NAFLD (OR: 0.6; 95% CI: 0.2–1.9; p = 0.4) was not associated with CVD development (Table 2).

Discussion

Primary findings

This study found that lean NAFLD had a similar CVD risk as non-lean NAFLD. Patients with lean NAFLD had a lower prevalence of diabetes and hypertension compared to patients with non-lean NAFLD. However, after adjusting for these factors, no difference was observed in the CVD risk between lean and non-lean NAFLD. Therefore, lean NAFLD should be treated with the same caution for CVD development as non-lean NAFLD.

In context with published literature

The significance of disease progression in lean NAFLD is not yet fully clarified. In particular, reports comparing the CVD incidence between lean and non-lean NAFLD are limited. A study that primarily included Hispanics (40.8% of whom had NAFLD without obesity) in the United States reported no significant difference in the incidence of new CVD between the lean and non-lean NAFLD groups [30]. Conversely, a study that included mainly Caucasians (approximately 10% of participants had lean NAFLD) in the United States revealed that lean NAFLD has a lower incidence of CVD compared to non-lean NAFLD [31]. Another study that included mainly Asian in China showed that the CVD risk was lower in lean NAFLD than in non-lean NAFLD [32]. Thus, whether CVD risk was higher in lean NAFLD than in non-lean NAFLD remains unclear. Furthermore, genetic polymorphisms such as PNPLA3 are associated with the development of lean NAFLD [33,34,35]. Because these genetic polymorphisms vary by race, the prevalence of lean NAFLD also varies by race. The prevalence of lean NAFLD varies from 7% in the United States [36] to 19% in Asia [37, 38]. Therefore, racial differences may affect the CVD risk in lean NAFLD and regional validation is needed. In this study, the proportion of lean NAFLD was 37.6%, which is higher than that in other studies. In this situation, this study revealed that lean NAFLD has the same CVD risk as non-lean NAFLD. The results provide further insight into the risk of CVD in patients with lean NAFLD.

The prevalence of dyslipidemia, hypertension and diabetes are higher in patients with non-lean NAFLD. In several previous studies demonstrated that patients with lean NAFLD had a similar incidence of CVD compared to non-lean NAFLD [30, 39]. Focusing on patient characteristics, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension were well controlled even in patients with non-lean NAFLD and it may affect the less impact on the CVD incidence.

Strengths and limitations

The strength of this study is that all patients received annual health checkup with the uniform protocol, which enabled an accurate assessment of new CVD development. In this study, the proportion of lean NAFLD was 37.6%, which is higher than that in other studies. In a previous study that investigated the epidemiology of NAFLD in Japan with a focus on lean NAFLD, the proportion of patients with lean NAFLD in Japan was 20.7%, which was lower than in our study [40]. Patient characteristics were similar between the previous study and this study. One reason for the difference in the prevalence of lean NAFLD is that this study was conducted in subjects with health check-up with at least more than 3 years of follow-up and the cohort is not a hospital or population-based cohort. Therefore, further validation studies with a hospital or population-based cohort are needed. This study was conducted at a single institution (in Japan only), there were a limited number of cases, and the results were only available for 3 years. Thus, the results may differ with more cases or longer-term observation.

Future implications

NAFLD is a risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma and decompensation as well as CVD [41,42,43]. However, the risk of CVD in lean NAFLD has not been fully elucidated. Our study shows that the CVD risk in lean NAFLD is as high as in non-lean NAFLD, indicating that even lean NAFLD should be considered a risk factor for CVD. The study was conducted in a population with a high proportion of lean NAFLD and the results provide a new insight associated with CVD risk in patients with lean NAFLD. These results provide important guidelines for the treatment of NAFLD. Recently, the new concept of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) has been proposed to detect high risk patients for complications. A previous study demonstrated that MAFLD better identified patients with worsening of CVD risk than NAFLD [14]. Investigation for the association between MAFLD and CVD incidence is also needed in a future study.

Conclusions

In conclusion, CVD incidence was comparable between patients with lean NAFLD and those with non-lean NAFLD. Therefore, CVD prevention is needed even in patients with lean NAFLD.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due (because the datasets have personal information) but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- NAFLD:

-

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- ALT:

-

Alanine aminotransferase

- AST:

-

Aspartate aminotransferase

- GGT:

-

Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase

- HDL:

-

High-density lipoprotein

- MAFLD:

-

Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease

- LDL:

-

Low-density lipoprotein

References

Younossi Z, Anstee QM, Marietti M, Hardy T, Henry L, Eslam M, et al. Global burden of NAFLD and NASH: trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;15(1):11–20.

Loomba R, Sanyal AJ. The global NAFLD epidemic. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10(11):686–90.

Sumida Y, Shima T, Mitsumoto Y, Katayama T, Umemura A, Yamaguchi K, et al. Epidemiology: pathogenesis, and diagnostic strategy of diabetic liver disease in Japan. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(12):4337.

Tampi RP, Wong VWS, Wong GLH, Shu SST, Chan HLY, Fung J, et al. Modelling the economic and clinical burden of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in East Asia: Data from Hong Kong. Hepatol Res. 2020;50(9):1024–31.

Cotter TG, Dong L, Holmen J, Gilroy R, Krong J, Charlton M. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: impact on healthcare resource utilization, liver transplantation and mortality in a large, integrated healthcare system. J Gastroenterol. 2020;55(7):722–30.

Sanyal AJ, Van Natta ML, Clark J, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Diehl A, Dasarathy S, et al. Prospective study of outcomes in adults with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(17):1559–69.

Seko Y, Kawanaka M, Fujii H, Iwaki M, Hayashi H, Toyoda H, et al. Age-dependent effects of diabetes and obesity on liver-related events in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Subanalysis of CLIONE in Asia. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;37(12):2313–20.

Tamaki N, Kurosaki M, Huang DQ, Loomba R. Noninvasive assessment of liver fibrosis and its clinical significance in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatol Res. 2022;52(6):497–507.

Tamaki N, Ahlholm N, Luukkonen PK, Porthan K, Sharpton SR, Ajmera V, et al. Risk of advanced fibrosis in first-degree relatives of patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Clin Invest. 2022;132(21):e162513.

Tamaki N, Imajo K, Sharpton S, Jung J, Kawamura N, Yoneda M, et al. Magnetic resonance elastography plus Fibrosis-4 versus FibroScan-aspartate aminotransferase in detection of candidates for pharmacological treatment of NASH-related fibrosis. Hepatology. 2022;75(3):661–72.

Anstee QM, Targher G, Day CP. Progression of NAFLD to diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease or cirrhosis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10(6):330–44.

Zheng Y, Ley SH, Hu FB. Global aetiology and epidemiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus and its complications. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018;14(2):88–98.

Li J, Zou B, Yeo YH, Feng Y, Xie X, Lee DH, et al. Prevalence, incidence, and outcome of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in Asia, 1999–2019: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;4(5):389–98.

Tsutsumi T, Eslam M, Kawaguchi T, Yamamura S, Kawaguchi A, Nakano D, et al. MAFLD better predicts the progression of atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk than NAFLD: Generalized estimating equation approach. Hepatol Res. 2021;51(11):1115–28.

Tamaki N, Kurosaki M, Higuchi M, Izumi N. Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk difference in metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatol Res. 2021;51(11):1172–3.

Zhang P, Dong X, Zhang W, Wang S, Chen C, Tang J, et al. Metabolic-associated fatty liver disease and the risk of cardiovascular disease. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2022;47(1):102063.

Adams LA, Lymp JF, St Sauver J, Sanderson SO, Lindor KD, Feldstein A, et al. The natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a population-based cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2005;129(1):113–21.

Kogiso T, Tokushige K. The current view of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(3):516.

Kogiso T, Sagawa T, Kodama K, Taniai M, Hashimoto E, Tokushige K. Long-term outcomes of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and the risk factors for mortality and hepatocellular carcinoma in a Japanese population. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;35(9):1579–89.

Tamaki N, Higuchi M, Kurosaki M, Loomba R, Izumi N, MRCH Liver Study Group. Risk difference of liver-related and cardiovascular events by liver fibrosis status in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(5):1171-1173.e2.

Kamada Y, Takahashi H, Shimizu M, Kawaguchi T, Sumida Y, Fujii H, et al. Clinical practice advice on lifestyle modification in the management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in Japan: an expert review. J Gastroenterol. 2021;56(12):1045–61.

Lim GEH, Tang A, Ng CH, Chin YH, Lim WH, Tan DJH, et al. An Observational Data Meta-analysis on the Differences in Prevalence and Risk Factors Between MAFLD vs NAFLD. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;S1542–3565(21):01276–83.

Tokushige K, Ikejima K, Ono M, Eguchi Y, Kamada Y, Itoh Y, et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis 2020. J Gastroenterol. 2021;56(11):951–63.

Hernaez R, Lazo M, Bonekamp S, Kamel I, Brancati FL, Guallar E, et al. Diagnostic accuracy and reliability of ultrasonography for the detection of fatty liver: a meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2011;54(3):1082–90.

Tamaki N, Kurosaki M, Takahashi Y, Itakura Y, Inada K, Kirino S, et al. Liver fibrosis and fatty liver as independent risk factors for cardiovascular disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;36(10):2960–6.

Committee of the Japan Diabetes Society on the Diagnostic Criteria of Diabetes Mellitus, Seino Y, Nanjo K, Tajima N, Kadowaki T, Kashiwagi A, et al. Report of the committee on the classification and diagnostic criteria of diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Investig. 2010;1(5):212–28.

Kinoshita M, Yokote K, Arai H, Iida M, Ishigaki Y, Ishibashi S, et al. Japan Atherosclerosis Society (JAS) Guidelines for Prevention of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Diseases 2017. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2018;25(9):846–984.

Umemura S, Arima H, Arima S, Asayama K, Dohi Y, Hirooka Y, et al. The Japanese Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension (JSH 2019). Hypertens Res. 2019;42(9):1235–481.

Kanda Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software “EZR” for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48(3):452–8.

Arvind A, Henson JB, Osganian SA, Nath C, Steinhagen LM, Memel ZN, et al. Risk of cardiovascular disease in individuals with Nonobese nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatol Commun. 2022;6(2):309–19.

Weinberg EM, Trinh HN, Firpi RJ, Bhamidimarri KR, Klein S, Durlam J, et al. Lean Americans with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease have lower rates of cirrhosis and comorbid diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19(5):996-1008.e6.

Lan Y, Lu Y, Li J, Hu S, Chen S, Wang Y, et al. Outcomes of subjects who are lean, overweight or obese with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A cohort study in China. Hepatol Commun. 2022;6(12):3393–405.

Fracanzani AL, Petta S, Lombardi R, Pisano G, Russello M, Consonni D, et al. Liver and cardiovascular damage in patients with lean nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, and association with visceral obesity. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(10):1604-1611.e1.

Lin H, Wong GLH, Whatling C, Chan AWH, Leung HHW, Tse CH, et al. Association of genetic variations with NAFLD in lean individuals. Liver Int. 2022;42(1):149–60.

Vilarinho S, Ajmera V, Zheng M, Loomba R. Emerging Role of Genomic Analysis in Clinical Evaluation of Lean Individuals With NAFLD. Hepatology. 2021;74(4):2241–50.

Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Negro F, Hallaji S, Younossi Y, Lam B, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in lean individuals in the United States. Medicine (Baltimore). 2012;91(6):319–27.

Fan JG, Kim SU, Wong VWS. New trends on obesity and NAFLD in Asia. J Hepatol. 2017;67(4):862–73.

Wei JL, Leung JCF, Loong TCW, Wong GLH, Yeung DKW, Chan RSM, et al. Prevalence and severity of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in non-obese patients: a population study using proton-magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(9):1306–14 quiz 1315.

Wijarnpreecha K, Li F, Lundin SK, Suresh D, Song MW, Tao C, et al. Higher mortality among lean patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease despite fewer metabolic comorbidities. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2023;57(9):1014–27.

Ito T, Ishigami M, Zou B, Tanaka T, Takahashi H, Kurosaki M, et al. The epidemiology of NAFLD and lean NAFLD in Japan: a meta-analysis with individual and forecasting analysis, 1995–2040. Hepatol Int. 2021;15(2):366–79.

Fujii H, Iwaki M, Hayashi H, Toyoda H, Oeda S, Hyogo H, et al. Clinical outcomes in biopsy-proven nonalcoholic fatty liver disease patients: a multicenter registry-based cohort study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;S1542–3565(22):00008–8.

Tamaki N, Ajmera V, Loomba R. Non-invasive methods for imaging hepatic steatosis and their clinical importance in NAFLD. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2022;18(1):55–66.

Higuchi M, Tamaki N, Kurosaki M, Inada K, Kirino S, Yamashita K, et al. Longitudinal association of magnetic resonance elastography-associated liver stiffness with complications and mortality. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2022;55(3):292–301.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Masayuki Kurosaki receives funding support from Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (grant number: JP23fk0210123h0001). Nobuharu Tamaki receives funding support from Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (grant number: JP22fk0210111h0001, JP22fk0210104h0001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study concept and design; S.I and N.T. data acquisition; All authors. data analysis and interpretation; S.I and N.T. drafting of the manuscript; S.I and N.T. critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; M.K, N.I. obtained funding; N.T, M.K. study supervision; M.K, N.I. All authors have read the final manuscript and approved it.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted following the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and with the consent of the ethics committee of the institution where the study was conducted (Musashino Red Cross Hospital, Approval Number: 1005). Informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Ishido, S., Tamaki, N., Takahashi, Y. et al. Risk of cardiovascular disease in lean patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. BMC Gastroenterol 23, 211 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-023-02848-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-023-02848-7