Abstract

Background

The common practice of clearing pineapple (Ananas comosus) residues for land preparation for cultivation is by burning, an unsustainable agricultural practice that causes environmental pollution. Chicken manure produced from the poultry industry is also increasing. Inappropriate disposal or treatment can pose harm to the environment and humans. In order to reduce environmental pollution, pineapple leaves and chicken manure slurry were co-composted to obtain high-quality organic fertilizer. The shredded pineapple leaves were thoroughly mixed with chicken manure slurry, chicken feed and molasses in polystyrene boxes. Co-compost temperature readings were taken three times daily.

Results

Nitrogen and P concentrations increased whereas C content was reduced throughout the co-composting. The CEC increased from 32.5 to 65.6 cmol kg-1 indicating humified organic material. Humic acid and ash contents also increased from 11.3% to 24.0% and 6.7% to 15.8%, respectively. The pH of the co-compost increased from 6.14 to 7.89. The final co-compost had no foul odour, low heavy metal content and comparable amount of nutrients. Seed germination indices of phytotoxicity test were above 80% of final co-compost. This suggests that the co-compost produced was phytotoxic-free and matured.

Conclusion

High-quality co-compost can be produced by co-composting pineapple leaves and chicken manure slurry and thus have potential to reduce environmental pollution that could result from poorly managed agricultural wastes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Approximately 13 t ha-1 of pineapple (Ananas comosus) residues are produced on tropical peat soils per cropping season in Malaysia (Ahmed et al. 2004a). The use of heavy machinery for transportation and removal of the pineapple residues from low land bearing capacity peat soil is not possible. Thus, pineapple residues are cleared by burning. Burning does not only cause haze and pollution but also causes peat fire which is difficult to control (Ahmed et al. 2004). Recently, more studies have been carried out to search for alternative solutions to handle these residues. For example, Ahmed et al. (2002, 2004a) concluded that the practice of burning pineapple residues before replanting does not improve pineapple fruit yield. Therefore, other uses of these beneficial agricultural wastes need to be explored. Animal manures have been effectively used as organic fertilizers due to their high nitrogen (N) content. There is a rapid growth of the chicken farm industry, and the daily manure production by a laying hen has been estimated as 138 g/day (25% dry substance) and 90 g/day (40% dry substance) by a broiler (Burton and Turner 2003). The manures provide important plant nutrients and organic matter (Sloan et al. 2003). Inappropriate treatment or disposal can harm the environment and humans as it can cause diseases as well as soil and groundwater pollution (Roeper et al. 2005). Usually, the nutrients in manures are in excess of crops' utilization, and this causes nutrient losses to the environment if poorly managed. For instance, organic N from animal manures can be converted to ammonia gas (NH3) through ammonia volatilization, and this leads to a net loss of N from soil systems (Mattsson 1998; Williams et al. 1999).

Co-composting is a preferred method of turning wastes and organic by-products into high nutrient end-products which can be applied as soil conditioners and amendments (Butler et al. 2001). In order to reduce environmental pollution, pineapple leaf residues and chicken manure slurry can be co-composted to produce organic fertilizers. Co-composting is an integrated waste management that involves biological decomposition and stabilization of two different types of wastes which complement each other (Ahring and Angelidaki et al. 1992; Angelidake and Ahring 1997) under conditions that allow development of thermophilic temperatures to eliminate pathogens and plant seeds (Gopinathan and Thirumurthy 2012). According to Smidt et al. (2007), co-composting can also be considered as a humification process that mineralizes original organic matter and turn residual organic matter into new organic materials called humic substances (Campitelli et al. 2006). These organic substances are one of the greatest carbon reservoirs on earth and can be used for agricultural, industrial, environmental and biomedical purposes (Pena-Mendez et al. 2005).

One of the most important factors affecting the successful use of agricultural manure compost such as chicken manure is its stability and maturity due to generation of differences in chemical composition and other characteristics in the finished compost. If unstable or immature compost is applied, anaerobic conditions will take place and application of immature compost releases phytotoxic compounds (Hu et al. 2008). The most important feature that determines whether finished compost is safe for use is its phytotoxicity. Compost stability is defined as the activity level of the microbial biomass (measured by rate of O2 uptake, production rate of CO2 and by the heat production) due to microbial activity (Wu et al. 2000). Compost maturity is the level of decomposition of phytotoxic organic substances being produced during the co-composting stage (Wu and Ma 2001).

One of the challenges of agricultural wastes management in Malaysia is to develop a new technique to manage these wastes. For example, this can be achieved by co-composting of pineapple leaf residues with chicken manure slurry to provide a better handling and management of these agricultural wastes, thus reducing environmental pollution and the risk of disease outbreak. This approach is one of the most suitable approaches for waste treatment due to the ever-increasing awareness about environmental pollution. In addition, co-composting allows resource recovery with many advantages such as reduced cost compared to separate treatment systems, developing a better handling and digestibility of the solid waste (Angelidake and Ahring 1997). Furthermore, co-composting leads to production of a better nutrient balance output which results in cost savings and also serves as an alternative to the use of chemical fertilizers.

In order to reduce environmental pollution, pineapple leaves and chicken manure slurry were co-composted to obtain a high-quality organic fertilizer. This study also investigated the effect of water extract from the organic fertilizer on the germination of maize seeds (Zea mays) so as to determine its phytotoxicity.

Methods

Co-composting site

The co-composting process was conducted at the Research Complex of Universiti Putra Malaysia Bintulu Sarawak Campus Malaysia. Four polystyrene boxes with length of 38 cm, width of 36 cm and height of 32 cm were used for the co-composting. A total of eight holes with 2-cm diameters were drilled on the sides of the boxes to allow good aeration during the co-composting process.

Raw materials and co-composting process

The pineapple leaves (Josephine variety) were obtained from Malaysia Agricultural Research and Development Institute (MARDI) Sessang Station, Saratok, Sarawak, Malaysia. Chicken manure was obtained from a chicken farm at Universiti Putra Malaysia Bintulu Sarawak Campus, Malaysia. The pineapple leaves were shredded and air-dried before being co-composted. The co-compost was produced by mixing 3.5 kg of shredded pineapple leaves + 350 g of chicken feed + 2.8 L of chicken manure slurry + 175 g of molasses. The chicken manure slurry was obtained by dissolving 350 g of chicken manure in 2.8 L of water and filtered. The pineapple leaves served as substrate (bulking material) and the chicken manure slurry was used as a source of water, microbes and nutrients. The chicken feed was included as energy source for the microbes. Molasses was added to provide carbohydrate for the microbes. The chicken feed and molasses were added gradually while mixing the pineapple leaves and chicken manure slurry so as to obtain a uniform mixture. The co-composting material was turned when necessary. The co-composting process was completed within 57 days. The ambient temperature and co-compost temperature were monitored daily (7 a.m., 1 p.m. and 7 p.m.) using a digital thermometer.

Physical, chemical and biological analyses

Initial characterization of the shredded pineapple leaves, chicken manure, chicken feed and molasses was carried out. The pineapple leaves were analysed for pH (Peech 1965), total organic matter (OM) and total carbon (C) using the combustion method (Chefetz et al. 1996), total N using micro-Kjeldahl method (Bremner and Lees 1949), total phosphorus (P) extracted using the method described by Tan (2003) and development of blue colour using Murphy and Riley (1962) method. Afterwards, C/N and C/P ratios were calculated. The leaching method described by Schollenberger and Dreibelbis (1945) was used to determine the cation exchange capacity (CEC) of the co-compost. Total potassium (K), calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), sodium (Na), zinc (Zn), copper (Cu), iron (Fe) and lead (Pb) were also determined. Humic acid content (HA) was determined using standard procedures (Stevenson 1994; Ahmed et al. 2004b). The pineapple leaves were also analysed for ash content, ammonium (NH4-N) and nitrate (NO3-N) (Keeney and Nelson 1982). Chicken manure, chicken feed and molasses were analysed for pH, total OM, total C, total N, total P, C/N and C/P ratio, total cations (K, Ca, Mg, Na, Zn, Cu, Fe and Mn), ash content, NH4-N and nitrate NO3-N using the methods that were previously cited.

The mixture of the shredded pineapple leaves, chicken manure slurry, chicken feed and molasses before co-composting and after co-composting was analysed for pH, total OM, total C, total N, total P, C/N and C/P ratio, CEC, total cations (K, Ca, Mg, Na, Zn, Cu, Fe and Mn), HA content, ash content, NH4-N and nitrate NO3-N, and electrical conductivity (EC). All analyses were done in triplicate. Changes in the co-compost colour, texture, size and odour were recorded through physical observation. Spread plate count method was carried out to quantify viable bacterial count on the first and final co-composting days, and chicken manure slurry (Brock and Madigan 1991). One gram of co-compost was weighed and inserted into a 9-mL sterile distilled water tube. Serial dilution was done by shaking the solution for 15 min, and then filtered using a sterile cheese cloth. Next, 1 mL of the solution was pipette into the next tube containing 9 mL of sterile distilled water to produce 1:100 dilution factor. Serial dilution was repeated to produce 10-3, 10-4, 10-5, 10-6 and 10-7 dilution factors. After that, 0.1 mL of solution from each tube was pipette into Nutrient Agar and spread by hockey stick. Samples were then incubated at 28°C for 48 h. Bacterial colony was counted by using colony counter under optical microscope (×40). The value of CFU was calculated as following:

Phytotoxicity test

A phytotoxicity test based on germination bioassay was carried out using the method described by Zucconi et al. (1981). Ten gram of co-compost was weighed and mixed with 100 mL of distilled water, and shaked for 24 h. The samples were then centrifuged for 20 min at 10,000 × g, and the supernatants were filtered through Whatman No. 42 filter paper. The extract was diluted five times and another one with distilled water only served as control. The pH and EC of these extract were determined. Ten FI HY Thai Super Sweet Corn maize seeds (Zea mays) were placed in 9-cm-diameter petri dishes lined with a filter paper (Whatman No. 42). Five millilitres of extract was pipette on each petri dish and petri dishes with 5 mL distilled water only served as a control. Parafilm was used to seal each petri dish to prevent water loss while allowing air penetration. The petri dishes were placed in a dark area for seeds germination. Each replicate was made up of ten seeds. Results are reported as means of the ten replicates. Seed germination and measurement of the length of root and shoot were done after 72 h for all the extracts and the control. The germination index (GI) was obtained by multiplying germination (G) and relative root growth (RRG), both expressed as percentage (%) of the control values. The formula is as follows:

where G% - (number of seeds germinated in a sample/number of seeds germinated in the control) × 100; RRG% - (mean root length in a sample/mean root length in the control) × 100;

Data analysis

Statistical Analysis System (SAS) version 9.2 was used for analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey test (P ≤ 0.05) means comparison of seed germination indices for the various co-composts.

Results

Selected nutrients composition of the raw materials used for co-composting

Table 1 shows the K, Mg, Ca and Na in the pineapple leaves were high in the order K > Mg > Ca > Na with values of 12,883.3, 3,662, 3,172.7 and 633.6 mg L-1, respectively. The pH of the pineapple leaves was slightly acidic (6.68). The pineapple leaves had very low concentrations of Zn (13.4 mg L-1), Cu (trace), Fe (1124.7 mg L-1) and Mn (212.3 mg L-1) compared to the co-compost. These values were consistent with those reported by (Wood End Research Laboratory, 2005). The chicken manure slurry had a lower C/N ratio (10.0) but it had higher concentrations of P (2,960 mg L-1), K (127,600 mg L-1), Ca (44,033 mg L-1), Na (5,002 mg L-1) and Mg (2,800 mg L-1) (Table 1). The chicken feed used also had a lower C/N ratio (13.76) compared to the shredded pineapple leaves. It also had higher concentrations of N (4.10%) and other nutrients. The molasses had a lower N concentration (0.51%).

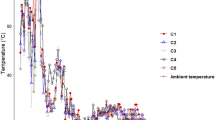

Co-composting process and temperature profile

Three typical co-composting phases were observed (Figure 1) during the co-composting process. The ambient temperature was between 25°C to 32.5°C throughout the co-composting period.

The temperature of the co-compost was at mesophilic stage in the morning (7 a.m.) and afternoon (1 p.m.) on the first day of co-composting. The temperature increased sharply to thermophilic stage (49.7°C) in the evening (7 p.m.) of the first day and further increased to 50.9°C on the second day. The thermophilic stage was maintained between 46°C to 57.8°C from the evening (7 p.m.) of day 1 until day 13 (Figure 1). The thermophilic phase continued until day 13 before it gradually decreased to below 45°C after day 14 to a second mesophilic stage as the food sources available to thermophilic organisms started to deplete. First turning over the co-compost was done on day 16 after which the temperature increased again to thermophilic stage (46.8°C).

A temperature range of 29.7°C to 43.6°C was maintained from day 17 to day 57 (period when the co-compost temperature was equal to ambient temperature). At the end of the co-composting, the average temperature of the finished co-compost product was 33.5°C which was the same as the ambient temperature of 33°C. On day 28, fungus started to grow on the pineapple co-compost. The fungus species belongs to Corprinus sp. due to characteristic shaggy ink-cap with white gills beneath the cap which later turned black and secret black liquid filled with spores.

Selected physiological and biochemical changes during co-composting

The matured co-compost product was brownish black in colour, soft, coarse and had an earthy smell compared to the yellowish green colour of the raw pineapple leaves. The residues were initially hard and rigid (Figure 2). The shredded pineapple leaves had higher C content of 51.3% (Table 1) and the moisture content of the final matured compost was 50%, slightly lower as compared to the initial value of 53.3% (Table 2).

Cation exchange capacity (a measure of the capacity of the co-compost to hold exchangeable cations to negatively charged surfaces of the co-compost) increased twofold from 32.5 to 65.6 cmol kg-1 (Table 2). The HA and ash contents at 57 days of co-composting increased from the initial amount of 11.3% to 24.0% and 6.7% to 15.8%, respectively.

The C/N ratio of the shredded pineapple leaves was 49.3 with C and N values of 51.3% and 1.04%, respectively, while the C/P ratio was 310.0 with a P value of 1,655 mg L-1 (0.165%). Nitrogen and P concentrations increased whereas C content reduced (Table 2). The initial C/N ratio of co-compost product was approximately 30 which decreased to 19.8 at the end of co-composting. However, the C/N value exceeded the range of 10 to 15.1 reported by Trautmann and Krasney (1997). The C/P ratio also decreased from 169.5 to 98.5.

The pH of the co-compost increased from 6.14 to 7.89 and its EC also increased from 5.1 to 6.9 dS m-1 (Table 2). The final co-compost product contained desired nutrients but it also had very low heavy metals hence suggesting that it is safe for use (Table 2). Nitrogen, P, K, Mg and Na increased except for calcium. The N, P, K, Mg and Na contents in the matured co-compost were 2.31%, 0.46%, 0.41%, 2.67%, 0.63% and 0.11%, respectively. The micronutrients also increased (Table 2). The NH4-N decreased from 182.0 to 63.0 mg L-1 whereas NO3-N content increased from 21.0 to 42.0 mg L-1.

Bacterial count and morphological identification and phytotoxicity germination test

The initial total bacteria count was about 1.55 × 1010 CFU mL-1 wet substrate when the chicken manure slurry was added and mixed together with the shredded pineapple leaves, chicken feed and molasses. The bacterial count decreased to 2.84 × 108 CFU mL-1 (Table 3). The maize seeds germination indices in the co-composted pineapple leaves were greater than 80% regardless of dilution factor (×10, ×100 and × 1,000) (Table 4). The heavy metal contents of the co-composted pineapple leaves (Tables 2) were lower than the thresholds provided by USEPA (1993).

Discussion

At the mesophilic stage of the co-composting (first day), the co-compost was predominated by mesophilic bacteria consuming readily available and digestible substrate (mainly sugars and protein compounds), leading to generation of substantial amount of metabolic heat energy that caused the temperature to increase sharply to thermophilic stage (Day and Shaw 2000). Once temperature exceeded 40°C, the high temperature was less favourable for mesophilic bacteria and the mesophilic microorganisms became less competitive. This was eventually followed by thermophilic or heat-loving microbes, mostly Bacillus species. These microbes are responsible for protein and other carbohydrate compounds decomposition. The more stable material such as lignin was oxidized in the prolonged thermophillic phase (Baffi et al. 2006). Bacteria and actinomycetes convert degradable substrates such as sugars and proteins, whereas fungi are the major microorganisms present when cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin are available (Ayed et al. 2007). On the day 16, the temperature increased again to 46.8°C, a thermophilic stage which turning over the compost and thorough mixing of undecomposed part of pineapple leaves for uniform decomposition. In addition, turning and mixing loosened the compost organic materials and improved aeration for aerobic microorganisms. At the end of the thermophilic phase, the co-compost temperature decreased, and it was not restored by turning or mixing (Trautmann and Krasny 1997).

At temperature range of 29.7°C to 43.6°C was maintained from day 17 till day 57 (period when the co-compost temperature was equal to ambient temperature) which suggests that the co-compost was mature. The temperature increased slightly on day 46 due to turning of the co-compost that was carried out in order to allow the compost to further stabilize. During this curing stage (a stage of low microbial activity which is responsible for stabilization of products in the active co-composting period (Day and Shaw 2000), the temperature decreased gradually until the temperature equaled ambient temperature. The Coprinus sp. mushrooms found growing on the co-compost were the fruiting bodies of some types of fungi, each of which was connected to an extensive network of hyphae. When the fungi start to dominate the co-compost, it indicates bacteria gradually died off. This was consistent with the decrease in bacterial count after co-composting (Table 3). Fungi are the major microorganisms present during this period of the stabilization process when cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin are available substrates and humification takes place (Ayed et al. 2007). When the co-composting is getting matured, not all compounds get fully broken down into simple ions. Microbes in the co-composting were able to link some of the chemical breakdown products together into long, intricate chains called polymers. These resist further decomposition and become part of the complex organic mixture called humus and the formation of humic compounds. An attestation of this is presented in Table 2 where HA content was higher after the co-composting compared to the first day (Graves and Hattemer 2000).

The shredded pineapple leaves had higher C content of 51.3%, and they were used as the main C source for the co-composting process (Table 1) due to its high cellulose (73.4%) and lignin (10.5%) contents (Abdul Khalil et al. 2006). The co-compost was softer and coarser at the end of co-composting process because the structure of shredded pineapple leaves was altered by cellulolytic and lignolytic microbes via breaking cellulose linkages present (Baharuddin et al. 2010). Factors such as high thermophillic temperature and aeration caused water loss and moisture content to be reduced during co-composting. High thermophillic temperature and aeration caused water loss and moisture content (Table 2) to be reduced during co-composting.

The high CEC, increase in ash content, and humic acid of the final co-compost product suggest that the organic material of the co-compost had been humified (Sullivan and Miller 2000). The initial C/N ratio of co-compost product decreased to 19.8 at the end of co-composting. However, the C/N value exceeded the range of 10 to 15.1 reported by Trautmann and Krasney (1997). This was mainly due to combination of hemicellulose and lignin that protect the cellulose (Kuhad et al. 1997). Wong et al. (2001) also reported that enzymes produced from microbes have difficulties in degrading lignin, and it shields the cellulose from further degradation. There was a reduction of C content at the end of co-composting, and this was due to active microbial cellulolytic degradation and microbial proliferation which immobilize N (Satisha and Devarajan 2007).

The release of mineral salts such as ammonium and phosphate during decomposition and mineralization of organic substances increased the EC during the co-composting process (Wong et al. 2001). In the early stages of co-composting, organic acids accumulate as by-product organic matter during decomposition by bacteria and fungi. The resulting increase in pH facilitates the growth of fungi which are active in the decomposition of lignin and cellulose. Usually, the organic acids break down further during co-composting and hence increase in pH (Trautmann and Krasney 1997). The increase in pH during the co-composting process was mainly due to protein degradation, a process that leads to ammonia release and rapid metabolic degradation of organic acids (Satisha and Devarajan 2007). The NH4-N decreased from 182.0 to 63.0 mg L-1 whereas NO3-N content increased from 21.0 to 42.0 mg L-1 suggesting that part of NH4 was mineralized to NO3. This may have partly increased the pH of the co-compost through evolution of ammonia (Trautmann and Krasney 1997).

The chicken manure slurry added served as microbial seeding, thus the application of effective microbes (EM) can be excluded to reduce the cost of a co-compost production. The maize seeds germination indices were greater than 80% regardless of dilution factor (×10, ×100 and × 1,000), indicating that the compost was phytotoxic-free and mature (Zucconi et al. 1981; Tiquia and Tam 1998). According to Tiquia and Tam (1998), seed germination index has proven to be the most sensitive parameter, capable of detecting low levels of toxicity affecting root growth and as well as high toxicity levels affecting seed germination. Compost stability based on temperature and CO2 evolution and its maturity based on seed germination are indeed two different characteristics of compost quality (Wu et al. 2000). Generally, the degree of stability and maturity of co-compost are closely linked to each other as more stable compost tends to be more mature. However, due to variation in the compost materials and co-composting process, some stable co-compost require longer period to decompose and degrade phytotoxic substances. As a result, both variables need to be assessed to ensure high-quality compost is produced. Wu and Ma (2001) showed that heavy metals cause phytotoxicity and higher than standard threshold concentration levels of heavy metals can delay compost maturation.

Conclusion

The final co-compost had no foul odour and was low heavy metals content, and comparable amount of nutrients. Seed germination indices of phytotoxicity test were above 80% for the final co-compost. The initial C/N ratio of co-compost was approximately 30.0, and it decreased to 19.8 at the end of co-composting. Chicken manure slurry and chicken feed had a lower C/N ratio, high moisture and N content compared to the pineapple leaves. Biodegradable pineapple leaves was high in organic carbon and has good bulking properties. By combining the two, the benefits of each can be used to optimize the co-composting process and the product by balancing and compensating the C/N ratio of the co-composting materials. High-quality co-compost can be produced by co-composting pineapple leaves and chicken manure slurry.

References

Abdul Khalil HPS, Siti Alwani M, Mohd Omar AK: Chemical composition, anatomy, lignin distribution, and cell wall structure of Malaysian plant waste fiber. Biores Technol 2006,1(2):220–232.

Ahmed OH, Husni MH, Anuar AR, Hanafi MM: Effect 240 journal of food, agriculture & environment, Vol. 7 (1), January 2009 of residue management practices on yield and economic viability of Malaysian pineapple production. J. Sustain. Agri 2002,20(4):83–94.

Ahmed OH, Husni MH, Anuar AR, Hanafi MM: Towards sustainable use of potassium in pineapple waste. The Sci World J 2004, 4: 1007–1013.

Ahmed OH, Husni MHA, Anuar AR, Hanafi MM, Angela EDS: A modified way of producing humic acid from composted pineapple leaves. J Sustain Agri 2004, 25: 129–139.

Ahring B, Angelidaki I, Johansen K: Anaerobic treatment of manure together with industrial waste. Water Sci Technol 1992,25(7):311–318.

Angelidake I, Ahring BK: Codigestion of olive oil mill wastewater with manure, household waste or sewage sludge. Biodegradation 1997, 8: 221–226. 10.1023/A:1008284527096

Ayed LB, Hassen A, Jedidi N, Saidi N, Olfa B, Murano F: Microbial C and N dynamics during composting of urban solid waste. Waste Manage Res 2007, 25: 24–29. 10.1177/0734242X07073783

Baffi C, Abate MTD, Nassisi A, Silva S, Benedetti A, Genevini PL, Adani F: Determination of biological stability in compost: a comparison of methodology. Soil Biol Biochem 2006, 39: 1284–1293.

Baharuddin AS, Lim SH, Yusof MZ, Abdul Rahman NA, Shah UK, Hassan MA, Wakisaka M, Sakai K, Shirai Y: Effects of palm oil mill effluent (POME) anaerobic sludge from 500 m3 of closed anaerobic methane digested tank on pressed-shredded empty fruit bunch (EFB) composting process. Afric J Biotechnol 2010,9(16):2427–2436.

Bremner JM, Lees H: Studies on soil organic matter part II: the extraction of organic matter from soil by neutral reagents. J Agri Sci 1949, 39: 274–279. 10.1017/S0021859600004214

Brock DT, Madigan TM: Biology of microorganism. 6th edition. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1991.

Burton CH, Turner C (2003) Manure management – treatment strategies for sustainable agriculture, 2nd edn. Proceedings of the MATRESA, EU Accompanying Measure Project: Silsoe Research Institute. Silsoe, Bedford, UK: Wrest Park; 2003.

Butler TA, Sikora LJ, Steinhilber PM, Douglass LW: Compost age and sample storage effects on matury indicators of biosolids compost. J Environ Qual 2001, 30: 2141–2148. 10.2134/jeq2001.2141

Campitelli PA, Velasco MI, Ceppi SB: Chemical and physicochemical characteristics of humic acids extracted from compost, soil and amended soil. Talanta 2006, 69: 1234–1239. 10.1016/j.talanta.2005.12.048

Chefetz B, Hatcher PH, Hadar Y, Chen Y: Chemical and biological characterization of organic matter during composting of municipal solid waste. J Environ Qual 1996, 25: 776–785.

Day M, Shaw K: Biological, chemical and physical processes of composting. In Compost utilization in horticultural cropping systems. Edited by: Stofella PJ, Kahn BA. Boca Raton, USA: Lewis Publishers; 2000.

Gopinathan M, Thirumurthy M: Evaluation of phytotoxicity for compost from organic fraction of municipal solid waste and paper & pulp mill sludge. Environ Res Engineer Manage 2012,1(59):47–51.

Graves RE, Hattemer GM: Part 637 Environmental engineering national engineering handbook: composting. Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture; 2000.

Hu Z, Lane R, Wen Z: Composting clam processing wastes in a laboratory and pilot-scale in-vessel system. Waste Manage 2008,29(1):180–185.

Keeney DR, Nelson DW: Nitrogen--inorganic forms. In Page AL (ed) Methods of soil analysis. Madison: WI: part 2, 2nd edn. ASA and SSSA; 1982.

Kuhad RC, Singh A, Erikson K: Microorganisms and enzymes involved in the degradation of plant fiber cell walls. Springer-Verleg, New York: Advances in biochemical engineering: biotechnology in the pulp and paper industry; 1997:45–125.

Laboratory WER: Interpreting waste and compost tests. Woods End Res Lab 2005,2(1):1–4.

Mattsson M: Influence of nitrogen nutrition and metabolism on ammonia volatilization in plants. Nutr Cycl Agroecosys 1998, 51: 35–40. 10.1023/A:1009796610912

Murphy J, Riley JP: A modified single solution method for the determination of phosphate in natural waters. ACTA Anal Chim 1962, 27: 31–36.

Peech HM: Hydrogen-ion activity. In Methods of soil analysis, part 2. Edited by: Black CA. WI, American Society of Agronomy: Madison; 1965.

Pena-Mendez EM, Havel J, Patocka J: Humic substances-compounds of still unknown structure: applications in agriculture, industry, environment, and biomedicine. J Appl Biomed 2005, 3: 13–24.

Roeper H, Khan S, Koerner I, Stegmann R (2005) Low-tech options for chicken manure treatment and application possibilities in agriculture. Proceedings Sardinia: Tenth International Waste Management and Landfill Symposium S. Cagliari, Italy: Margherita di Pula; 2005.

Satisha GC, Devarajan L: Effect of amendments on windrow composting of sugar industry pressmud. Waste Manage 2007, 27: 1083–1091. 10.1016/j.wasman.2006.04.020

Schollenberger CJ, Dreibelbis FR: Determination of exchange capacity and exchangeable bases in soil – ammonium acetate method. Soil Sci 1945, 59: 13–24. 10.1097/00010694-194501000-00004

Sloan DR, Kidder G, Jacobs RD: Poultry manure as a fertilizer, PS1 IFAS extension. Gainesville, FL: University of Florida; 2003:241.

Smidt E, Meissl K, Schmutzer M, Hinterstoisse B: Co-composting of lignin to build of humic substances- strategies in waste management to improve compost quality. Ind Crop Prod 2007, 27: 196–201.

Stevenson FJ: Humus chemistry: genesis, composition and reactions. 2nd edition. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1994.

Sullivan DM, Miller RO: Compost quality attributes, measurements, and variability. In Compost utilization in horticultural cropping systems. Edited by: Stoffella PJ, Kahn BA. Boca Raton, USA: Lewis Publishers; 2000:95–120.

Tan KH: Soil sampling, preparation and analysis. New York: Taylor & Francis Inc.; 2003.

Tiquia SM, Tam FY: Elimination of phytotoxicity during cocomposting of spent pig-manure sawdust litter and pig sludge. Biores Technol 1998, 65: 43–49. 10.1016/S0960-8524(98)00024-8

Trautmann NM, Krasny ME: Chapter 1: the science of composting, in: composting in the classroom. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University; 1997:1–5.

USEPA: Standards for the use or disposal of sewage sludge; final rules. Fed Regist 1993, 58: 9248–9415.

Williams CM, Barker JC, Sims JT: Management and utilization of poultry wastes. Rev Environ Contam T 1999, 162: 105–157. 10.1007/978-1-4612-1528-8_3

Wong JWC, Mak KF, Chan NW, Lam A, Fang M, Zhou LX, Wu QT, Liao XD: Co-composting of soybean residues and leaves in Hong Kong. Biores Technol 2001, 76: 99–106. 10.1016/S0960-8524(00)00103-6

Wu L, Ma LQ: Effects of sample storage on biosolids compost stability and maturity evaluation. J Environ Qual 2001, 30: 222–228. 10.2134/jeq2001.301222x

Wu L, Ma LQ, Martinez GA: Comparation of methods for evaluating stability and maturity of biosolids compost. J Environ Qual 2000, 29: 424–429.

Zucconi F, Pera A, Forte M, de Bertoldi M: Evaluating toxicity of immature compost. BioCycle 1981, 22: 54–57.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Universiti Putra Malaysia and Ministry of Higher Education, Malaysia for the financial and technical support of this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Authors’ contributions

All authors, HYC, OHA, SK, and NMAM, have made adequate effort on all parts of the work necessary for the development of this manuscript according to his/her expertise. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Ch'ng, H.Y., Ahmed, O.H., Kassim, S. et al. Co-composting of pineapple leaves and chicken manure slurry. Int J Recycl Org Waste Agricult 2, 23 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/2251-7715-2-23

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/2251-7715-2-23