Abstract

Background

The translocation of plants or animals between populations has been used in conservation to reinforce populations of threatened species, and may be used in the future to buffer species’ ranges from the anticipated effects of environmental change. This population admixture can result in outbreeding, and the resulting “hybrid” offspring can be either fitter (heterosis) or less fit (outbreeding depression) than their parents. Outbreeding depression has the potential to undermine conservation plans that mix populations of declining or threatened species.

Methods

We searched for literature documenting phenotypic responses to intraspecific outbreeding between natural populations of animal and plant species. Outbreeding responses were summarised as log-response ratios that compared hybrid with mid-parent phenotypes (528 effect sizes from 98 studies). These data included effect sizes from both fitness components (survival, viability and fecundity traits) and other traits (e.g. morphological, physiological, defence), and were pooled using Bayesian mixed-effects meta-analysis.

Results

There was no overall effect of outbreeding on hybrid phenotypes (overall pooled effect = +2.61% phenotypic change relative to parents, 95% credible interval (CI) −1.03–6.60%). However, fitness component traits responded significantly more negatively to outbreeding than traits less directly linked with fitness. Our model predicted a significant 6.9% F1 generation benefit to outcrossing through non-fitness traits (CI 2.7–11.2%), but no significant benefit to these traits in the F2 (3.5%; CI −4.3–12.2%). Fitness component traits were predicted to suffer a cost (−8.8%) relative to parents in the F2 (CI −14.1– − 2.5%), but not in the F1 (+1.3%; CI −2.1–5.4%). Between-study variation accounted for 39.5% of heterogeneity in outbreeding responses, leaving 27.1% of heterogeneity between effect sizes within studies and 33.4% attributable to measurement error within effect sizes.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrates consistent effects of trait type on responses to intraspecific outbreeding, and indicates the potential for outbreeding depression in the F2. However, our analyses also reveal significant heterogeneity in outbreeding responses within and among studies. Thus, outbreeding costs will not always occur. Conservation practitioners may be able to anticipate when such outbreeding depression should arise using an existing decision-making framework that takes into account the context of hybridising populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The need to ensure natural populations have sufficient genetic variation for their long-term sustainability has long been recognized [1, 2]. Genetic diversity provides the raw genetic material upon which natural selection can act allowing adaption to changes in the environment (including current anthropogenic changes such as eutrophication and climate change). By definition, genetic diversity includes allelic and genotypic variants conferring both detrimental and beneficial effects on the phenotype and fitness. When sexual reproduction occurs among related individuals, detrimental variation can be exposed as a decline in fitness of the resulting offspring, an effect known as inbreeding depression [3, 4]. Inbreeding becomes more likely as populations become smaller in size, and where this leads to inbreeding depression it may contribute to the extinction of small populations [5, 6]. However, the natural movement or human-aided translocation of individuals into an inbred population from a separate population can result in fitness recovery, or “genetic rescue” within the inbred population [7–13].

Despite the potential benefits of creating hybrid populations, conservation practitioners remain cautious about applying population translocations widely as a tool to enhance population sustainability [14]. This caution may be well founded, since it has been shown that in some circumstances, population admixture can lead to a reduction in fitness of hybrid individuals within the mixed population, called “outbreeding depression” [8, 15, 16]. The basis of such a fitness reduction is that the populations being mixed may have become adapted to the specific environments in which they exist (extrinsic outbreeding depression), or they may have diverged genetically such that genomic incompatibilities are exposed upon population mixing (intrinsic outbreeding depression, also known as the break up of co-adapted gene complexes [15, 17, 18]). Hybrid viability can also be undermined by chromosomal rearrangements that differentiate parent populations (including inversions, translocations and centric fusions [19–21]). These reductions in fitness can be observed readily at one extreme of the inbreeding-outbreeding continuum, in hybrid offspring derived from mating between individuals of different species [20, 22, 23].

Extrinsic outbreeding depression is driven by adaptation of parent populations to different environments [18]. Hybrids individuals are expected on average to possess a phenotype intermediate to that of the parents (considering only additive gene effects [24]) and so may be unfit in either or both parental environments. The potential for extrinsic outbreeding depression is thought to increase with environmental distance between parental populations, and with duration of isolation of the parent populations in these separate environments [21]. Intrinsic outbreeding depression arises as a further consequence of evolution in allopatry. Fitness often depends on the integrated functioning of alleles at different gene loci (“co-adapted gene complexes”). When parent populations have been isolated from each other for a sufficient number of generations, they can evolve to “find” different solutions to the problem of adaptation that depend upon different sets of alleles [25]. While these co-adapted gene sets may work well within each population, their functioning can break down if mixed in hybrid individuals with alleles with which they have never been tested. Intrinsic outbreeding depression occurs when hybrid fitness falls below that of the mid-parent value [15]. Theory predicts that the potential for intrinsic outbreeding depression should be associated with genetic distance between parent populations [17, 26]. However, there is little consistent empirical evidence for this [15, 16, 27].

Risks of both intrinsic and extrinsic outbreeding depression are expected to be low where migration among parental populations is high, or where the populations are recently isolated. This is because the genetic composition of the parent populations will be more homogeneous, limiting the extent of adaptive differentiation and development of the divergent genetic architectures that lead to outbreeding depression [21, 28].

A growing body of evidence exists on the phenotypic effects of intraspecific outbreeding, and there have been several attempts to synthesise this literature. Edmands reviewed the relative risks of inbreeding and outbreeding [15]. She found that outbreeding responses in the F2 may be comparable to the effects of close inbreeding, and that F2 phenotypic responses to outbreeding were significantly more negative than F1 responses. McClelland and Naish [16] carried out a meta-analysis that focussed on the phenotypic consequences of outbreeding within and between fish species. They found overall positive responses to outbreeding, but were not able to identify factors that consistently explained variation in outbreeding responses. Together, these two papers have improved our understanding of responses to outbreeding, but both suffer from problems. Edmands’ analysis was limited to study-systems for which data were available on both responses to inbreeding and responses to outbreeding, and did not consider or control for within-study measurement error. McClelland and Naish’s work was limited in taxonomic scope. In addition, these articles neither reviewed the literature systematically nor addressed the problem of the occurrence of multiple outbreeding effect-size estimates within each study. Thus, there is a need for an expanded synthesis of the evidence on outbreeding responses, in order to guide future conservation management that results in outbreeding (including translocations).

We carried out a systematic review to determine whether there is a net change in fitness or phenotype in hybrid offspring arising from mating between individuals from separate populations. We also assessed whether outbreeding responses varied through the generations following outbreeding, varied for different trait types, or with geographical, high-level phylogenetic, environmental or life history variables.

Methods

Question formulation

The core question and scope of this systematic review were refined at a review group meeting, held at Losehill Hall, Derbyshire 28–29 October 2008. The review group included representation from UK conservation agencies, conservation charities, and scientists specialising in the field of conservation genetics. When a draft systematic review protocol was developed, the review group were able to feed back on the plans for the review. This a-priori review protocol [29] was also peer-reviewed and published on-line. This process improved the review structure and scope markedly, and helped to ensure relevance to stakeholders who represented end-users of the review’s results.

Literature searches

Scope of literature searches

On 5 October 2010 we searched computer databases and online repositories (Table 1), in order to identify articles, studies and datasets relevant to the review question.

Literature search terms

We used the search strings listed in Table 2 to retrieve articles from online databases and repositories. Where database search facilities allowed, we used search strings in Table 2 as follows. Compound search strings were generated by combining each of the search strings in groups (i) and (ii) with each of the strings in group (iii) for a total of 9 + 15 = 24 search strings (Table 2). Search terms in group (iv) are catch-all phrases that were used to carry out searches without combination into more complex strings (Table 2). Some databases provided only limited support for compound search queries, or did not support Boolean operators. In these cases we employed a simplified version of the search (Additional file 1: Table S1).

Study inclusion criteria

Relevant subjects and scope

Relevant subjects were defined as individuals of any natural population of animal or plant (or experimental individuals derived directly therefrom), at any location globally, and their progeny. We defined natural populations as naturally occurring, naturalised or (re-) introduced populations that occupy natural habitat, and that persist in the absence of human intervention. Studies that described populations with alternative phraseology such as “provenance”, “land-race” or “cultivar” were retained as potentially relevant until it could be ascertained whether they fitted the criteria given in this section.

In this review we focussed exclusively on outbreeding effects on phenotype occurring within the post-zygotic portion of the life cycle. This focus excluded pre-zygotic mating incompatibilities from consideration, but included, for example, progeny traits such as germination success and egg hatching rate. We excluded studies documenting outbreeding effects resulting from crosses amongst agricultural cultivars or strains, or populations under captive management (e.g. zoo populations). These populations have been subjected to a different selective regime (e.g. directional selection for yield and or disease resistance, adaptation to captivity) than may prevail in natural populations. We did, however, include studies that observed the effects of hybridisation between natural populations and farmed individuals of the same species. These hybridisation events are relevant to the conservation of natural populations and have been known to occur in aquaculture and fisheries contexts, for example. We excluded studies documenting outbreeding effects in microorganisms. This was because (1) many groups of microorganisms are poorly characterised from a taxonomic point of view (2) the meaning of outbreeding differs for some of these microorganisms whose genomes may be non-recombining, or that may engage in horizontal gene transfer, and (3) bacteria are not themselves the target of translocation between sites or populations within the context of conservation plans. Studies focussing on crosses or hybridisation among different recognised species (but not sub-species) were excluded. This is because the costs and benefits of interspecific hybridisation are better known than those stemming from intraspecific hybridisation. In addition, the conservation community has a greater awareness of hybridisation involving multiple species because conservation actions are often arranged around particular known species of conservation concern. Studies focussing on crosses or hybridisation among taxa with uncertain taxonomy at the species level were excluded, to avoid inadvertent inclusion of studies involving interspecific hybridisation.

Types of intervention

We considered the “interventions” listed below:

-

Outbreeding resulting from experimental translocation of individuals from a donor population to a geographically separated recipient population.

-

Outbreeding resulting from observed natural migration between geographically separated populations.

-

Outbreeding resulting from experimental crosses between individuals from geographically separated populations.

-

Outbreeding resulting from experimental crosses between individuals separated by known distances within a single population.

Types of comparator

We defined the treatment group and corresponding reference (comparator) group on the basis of pedigree information presented within individual studies. The treatment group common to the interventions above is composed of hybrid offspring arising from outcrossing between geographically defined populations or across space within a population. The corresponding comparator or reference group(s) are composed of less outbred (but not deliberately inbred) individuals stemming from either within-population crosses or such crosses occurring over a smaller physical distance than those in the treatment group. The comparison made in this review is between the phenotype or fitness of hybrid individuals and that of their less outbred parent lineages. Thus, regardless of the intervention type, the phenotype or fitness of parent individuals or non-hybrid offspring from the “source populations” and that of their hybrid offspring were required for inclusion of any study in the review.

Types of outcome

Relevant outcomes were measures of the phenotype or traits of individuals within “reference” parental lineages or “treatment” lineages resulting from outbreeding between these former. Pre-zygotic traits were excluded. We made the assumption that phenotypes were a function of the genes of the individuals measured and their immediate measurement environment. Thus, we also assumed that phenotypes were not influenced by maternal or other persistent environmental effects.

Types of study

Relevant studies were defined as those with treatment and reference groups that could be identified using pedigree information, and that also recorded appropriate outcome measures. We did not include studies that used mean d-squared to infer the extent of outbreeding using molecular markers. This is because mean d-squared may not provide a reliable estimate of the position of any individual on the inbreeding–outbreeding continuum [30]. We chose to exclude these studies because (1) there is no identifiable reference class to make a comparison with and (2) because doubt exists as to whether the measure faithfully reflects differences in the quantity of inbreeding or outbreeding that occurred to create an individual’s genome [30]. Articles that reviewed or meta-analysed the existing literature were excluded from the review, although any missing records from their bibliographies were added to the project database and assessed against the criteria defined above.

Potential sources of heterogeneity

We investigated the relationship between outbreeding effect sizes and several sources of heterogeneity (i.e. effect modifiers; hereafter “explanatory variables”), as described below (see Additional file 1: Text S2 for full details).

-

Taxon category High-level taxonomic category for species; one of amphibian, bony fish, crustacean, gastropod, insect, mammal, bivalve, nematode, plant, reptile, tunicate

-

Lifespan category Description of the longevity of an organism e.g. short-, ≤ 2 years; or long-lived, > 2 years

-

Physical distance Euclidian distance separating outcrossed populations, km

-

Hybrid generation Generation following outbreeding in which phenotype was observed; F1, F2, etc.

-

Trait type Categorical descriptor of trait; one of defence, development, fecundity, fitness, growth-rate, physiology, size, survival, viability, or other

-

Fitness class Categorical description of whether the phenotypic measure was a component of fitness (fecundity, survival, viability, integrated/ compound measures of fitness), or was more distantly related to fitness (all other trait types)

-

Trait timing Categorical description of the timing of expression or measurement of a trait (early, mid or late), relative to the life-history of the organism in question

-

Mating system Predominant sexual reproductive mode of the study organism; highly inbreeding, mixed mating, highly outbreeding

-

Observation environment Categorical description of the environment in which the phenotype was expressed and observed; one of lab, common garden or natural population or habitat

Article screening strategy

We assessed articles for inclusion in the review based on an hierarchical assessment of relevance. This was done by assessing article titles, followed by reading the abstract of articles with relevant titles, followed by reading the full-text of articles with relevant abstracts (Additional file 1: Text S3). The objectivity of the article assessment procedure was determined using the Kappa coefficient of agreement applied to independent assessments of article subsets ([31]; Additional file 1: Text S3).

Data extraction

We attempted to extract data from all articles assessed as relevant at the full-text article assessment stage. We approached the authors of articles to request raw data or data summaries in cases where articles did not present the data needed for meta-analysis.

Data for traits measured on a continuous scale were extracted as mean values for each outcrossing class (outbred treatment individuals, parental comparator lineages). We also extracted standard error estimates for these means and recorded the number of families contributing to each cross class and, where the information was available, the number of individuals measured per family and/or cross class. Where separate data were available for both parent lineages, these were summarised as a mean (mid-parent) value for the comparator group. Data for separate traits were extracted separately. In some studies that used more than two parental comparator lineages (populations) trait summaries were not available for each separate parental lineage. In these studies the comparator data were taken as mean values (within traits) across all parent lineages. Equivalently, in some cases, trait data from treatment individuals (outbred offspring) were available only as mean values across crosses or population pairs.

Data for traits measured as counts (e.g. survival) were extracted as successes (survival) and failures (e.g. non-survival, death), for each of the outcrossing classes. In cases where proportion data were presented, these were used to estimate the original counts by multiplication with the sample size (number of individuals) followed by rounding to a whole number. Where proportions were given as a mean across families with associated standard error we treated these in the same way as for the continuous data, described above. Data extraction was not duplicated but consistency of the extracted data was checked and extraction of data from difficult articles was discussed.

Study quality assessment

We assessed the quality of the relevant full-text articles by determining, for each article, a score based on the presence or absence of attributes that indicated its internal or external validity. The attributes that were scored are summarised in Table 3. We assigned points for each of the desired attributes possessed by each study and measured any studies’ overall quality as the sum of points scored across the component attributes. The maximum possible quality score was 7 points, one for each of the seven attributes recorded. Assessments of study quality are not often presented in traditional reviews and meta-analyses, but their use is considered best practice in systematic reviews within ecology and evolution [32].

Data synthesis

Effect size metric

We summarised outbreeding effect sizes for trait data measured on a continuous scale (e.g. growth rate, seed mass production, lifespan) using the log response ratio [33]:

where μH and μP are trait mean values for the outbred (hybrid) treatment group and parental comparator groups respectively. We estimated the study measurement error variance as [33]:

where n H and n P are respective sample sizes (numbers of families) measured for the hybrid treatment and parental comparator groups, and S is the pooled standard deviation for the hybrid treatment group and the parental comparator group. We used n H and n P (number of families) to convert standard errors reported within articles to standard deviations, separately for the treatment and comparator groups. These were then pooled to yield S. ([33]; p. 22).

Where trait data were binomially distributed we calculated effect sizes as the log risk ratio [33]:

In this case we estimated the study measurement error variance as [33]:

In these equations, a and c are the numbers (counts) of successes (e.g. survival or reproduction of tested individuals) in treatment and reference groups. n H and n P in this case refer respectively to the total number of individuals tested in hybrid treatment and parental comparator groups. Our effect sizes represent measures of intrinsic outbreeding responses, i.e. deviation of hybrid from mid-parent phenotypes, due predominantly to dominance and epistatic gene effects [15, 17, 18].

Meta-analysis

Effect size estimates were meta-analysed using the R package MCMCglmm [34], which provides functions for fitting generalised linear mixed models in a Bayesian framework, via a Markov chain Monte Carlo sampler. Models fitted by MCMCglmm extend to fixed- and random-effects meta-analyses that model and take into account the study measurement error variance ([35]; equivalent to weighting the analysis by the inverse of the study measurement error variance in a traditional meta-analysis). All models were run for a total of 6 × 105 iterations, with a burn in of 105 iterations and a subsequent thin interval of 50 iterations. This sampling schema leads to a total MCMC sample size of 1000 for each fitted model. We used multivariate normal priors with mean 0 and variance 1010 for the fixed effects. Priors for random effects were uniform improper distributions on the standard deviation of the random effects as recommended in [36]. Measurement error variance estimates (mev) were fitted as a set of random effects, and these we assumed to be known without error. Study identities (Study) were fitted as random effects in all models, in order to capture and model variation in outbreeding contexts. Explanatory variables of interest were fitted as fixed effects. Note that the distinction between “fixed” and random effects is arbitrary in a Bayesian modelling framework such as used here, where all effects are random. However, we retain separate notation for fixed and random effects specifications to facilitate conceptual distinction between explanatory variables (“fixed” effects of primary interest) and study identities (random effects whose variation we wish to account for and estimate). Additional file 1: Text S4 gives further details on model specification.

In cases where individual model parameters represented pooled effects of interest, we used posterior means and 95% credible intervals for the parameters to derive predictive intervals for the effect sizes. In other cases, we predicted pooled effect sizes by summing over the posterior distributions of their component parameters, and then summarising these as above. The meta-effect sizes (parameter estimates) were considered statistically “significant” when their 95% credible interval did not bracket 0. Results of the meta-analyses were presented graphically using forest plots for effect sizes and pooled effect sizes. Model goodness of fit was assessed via the Deviance Information Criterion DIC; [37]. DIC is subject to variation between separate runs of identically specified MCMCglmm models, due to Monte Carlo error, even in a well-fitted model. Therefore, we carried out three replicate model runs for each model fitted to ensure that we compared the goodness of fit of competing models fairly and consistently. Models were checked to assess the degree of mixing and convergence by visual inspection of the sampled MCMC chains of component parameters, by evaluating chain autocorrelation, and by determining the effective size of MCMC chains. MCMCglmm initiates a single MCMC chain during model fitting. Therefore we also assessed MCMC chain convergence using Gelman-Rubin diagnostics applied to pairs of replicate model runs initiated independently from over-dispersed starting values.

We took two approaches to fitting explanatory variables using MCMCglmm. In the first we fitted models with only a single fixed effect (one model for each explanatory variable). The aim of fitting these models was to explore variation in outbreeding responses with predictors of these responses. We considered variables to be potentially relevant in explaining outbreeding responses when any of their component parameters differed significantly from zero. Trait type and fitness class (fitness component and other traits) contained redundant information; levels of trait type were nested within levels of fitness class. Therefore, we fitted the fitness component vs. other traits comparison in two ways. First as a post-hoc orthogonal contrast within the trait.type predictor, and second using the fitness class predictor. Variation in outbreeding responses among trait types within the fitness component trait class was investigated using further post-hoc contrasts.

In the second approach to modelling outbreeding responses we fitted multiple explanatory variables within a single maximal model, which had a fixed-effects specification as follows:

We omitted fitness class from this model because this predictor and the trait type predictor contained redundant information. It was also necessary to omit physical distance from the model reduction analysis, since we had incomplete information on this predictor across the dataset. After fitting the maximal model, we then defined a minimal model by elimination of those fixed effects that did not contribute to improving the model fit (as judged by changes in the deviance information criterion, DIC). The maximal model included main effects only (no interactions among fixed effects). We carried out three replicate model runs for the maximal model and each nested model derived from this, to ensure that fixed effects were eliminated or retained based on consistent changes in DIC. Only predictors whose exclusion resulted in a consistent cost to model fit were retained in the model.

We were also interested specifically in whether our minimal model implied either net costs or benefits to outbreeding in different generations. Therefore we ran an additional model that included an interaction between the explanatory variable identified by our minimal model and hybrid generation. We give results for similar models combining generation with each of the other explanatory variables in Additional file 1: Figure S12.

We evaluated the proportion of the heterogeneity in outbreeding responses attributable to variation among studies, and the proportion of heterogeneity associated with the residual variance component using the approach of Sutton et al. [38]. However, we took the median of the mev as our estimate of the typical measurement error variance, instead of equation 9 in [39], which gave a poor estimate of central tendency of the mev for our data.

Publication bias

We used the R package metafor [ [40] ] to create enhanced funnel plots as a graphical check for the presence of funnel-plot asymmetry (indicating publication bias). We used study-mean effect sizes to create study-level funnel plots, since publication bias is likely to operate at the level of studies rather than individual effect sizes within studies (effect sizes within studies are likely to be correlated). An additional reason for doing this was that the number of effect sizes per study in our data was unbalanced, undermining any assessment of bias based on the full dataset. We used the median measurement error variance for the effect sizes within each study as a “typical” study-level measurement error variance. We also used the Egger regression to test for the presence of funnel-plot asymmetry [41], using study-level data, as above.

Sensitivity analyses

In order to understand whether outbreeding responses were sensitive to study quality we included our study quality variable in both a single-predictor meta-analysis and in the model reduction analysis, as described above. We also trialled inverse gamma and “parameter expanded” proper Cauchy priors for the standard deviation of the random effects, as alternatives to the improper flat priors that we used. Variance component estimates were found to be insensitive to the choice of prior. Finally we tested whether our model and its underlying assumptions was consistent with the observed data, using posterior predictive simulation [42]. Full details and results for the posterior predictive simulation are given in Additional file 1: Text S7 and Additional file 1: Figure S8.

Results

Review descriptive statistics

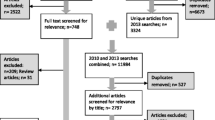

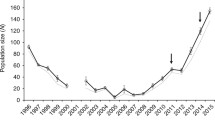

The primary literature search (conducted 5 October 2010) yielded 9631 papers (Table 4; Additional file 2). The minimum set of data necessary for meta-analysis was obtained for a total of 93 articles published between 1987 and 2010 (Table 5; Additional file 2, and Additional file 3). Over this period, articles on phenotypic responses to between-population outbreeding increased in publication frequency roughly linearly with time (Figure 1). Most (58.1%) of the 93 articles in the review used plants as study taxa (Figure 2). Fish were also well represented in the review dataset. The numbers of effect size estimates contributed by different taxonomic groups corresponded approximately with the numbers of articles focussing on these groups in the review (Figure 2). 61.2% of effect sizes were for traits that were components of fitness (fecundity, survival, viability and compound measures of fitness; Figure 3).

Quantitative synthesis

Study-mean effect sizes were evenly distributed in funnel plots (Additional file 1: Figures S5, S6), and showed no obvious signs of asymmetry indicative of publication bias. The Egger test for funnel plot asymmetry was non-significant (intercept = 0.41, p = 0.166).

Meta-analyses with a single explanatory variable

On average, hybrid offspring experienced neither a phenotypic benefit nor a cost to outcrossing (+2.6% phenotypic change relative to parents; 95% credible interval −1.0–6.4%; pMCMC (Bayesian p-value) = 0.156; Figure 4a).

Variation of outbreeding responses with explanatory variables (effect modifiers). Outbreeding responses are given as proportion changes in phenotype relative to the mid-parent phenotype. An outbreeding response of zero means hybrid offspring have phenotype equivalent to the mid-parent value. Positive values represent phenotypic benefit relative to parent lineages. (a) Overall pooled outbreeding response (for a model fitting only an intercept). (b) – (l) Variation of outbreeding responses with individual explanatory variables. Points give posterior means for the pooled effect sizes (on the relative phenotypic scale). Error bars bracket the corresponding 95% credible interval. n ST and n ES give respectively the number of studies and the number of effect sizes underpinning each estimate. See Methods and Additional file 1: Text S2 for a description of the explanatory variables.

The trait type, fitness class (whether a trait was a component of fitness or not), trait timing, generation, taxon category and observation environment predictors contained individual factor levels with which outbreeding responses varied significantly (Figure 4; Additional file 1: Table S9). Of these, only trait type, fitness class and trait timing improved overall model goodness-of-fit, as judged by DIC (Table 6). Physical distance separating parent populations improved model fit, according to DIC, but parameters for this explanatory variable did not differ significantly from 0. No other variables were significant predictors of outbreeding responses (Figure 4; Table 6; Additional file 1: Table S9).

Outbreeding responses varied significantly with trait type. Growth-rate and “other” trait types showed the greatest hybrid benefit following outcrossing (Figure 4d; Additional file 1: Table S9). Defence, survival and viability trait types showed the most negative responses to outbreeding. Orthogonal contrasts within the trait type predictor indicated that fitness component traits (survival, viability, fecundity traits and compound measures of fitness) responded more negatively to outbreeding than all other traits (pMCMC = 0.024; Figure 5). This difference appeared to be driven by survival and viability traits, which responded significantly more negatively to outbreeding than the remaining fitness component traits (pMCMC = 0.004; Figure 5). The outbreeding responses of viability traits did not differ significantly from those of the remaining later acting survival traits (pMCMC = 0.76; Additional file 1: Table S12).

Outbreeding responses vary between fitness component and all other traits, and between survival traits (survival and viability) and other traits within the fitness component category (fecundity traits and integrated or multiplicative measures of fitness). Posterior means and credible intervals were estimated as contrasts within the trait type predictor. X-axis scale, point estimates, error bars and abbreviations as in Figure 4.

The more negative response of fitness components to outbreeding was borne out by our fitness class predictor, which grouped trait types depending on whether they were components of fitness or not. Outbreeding responses were consistently less positive for traits that were components of fitness relative to other traits (pMCMC < 0.001; Figure 4c, Additional file 1: Table S9). Fitness component traits showed outbreeding responses that were close to the mid-parent value (0.0% phenotypic change relative to the mid-parent), and not consistently different from zero (Figure 4c, Additional file 1: Table S9). The remaining non-fitness component traits conferred a consistent benefit to hybrids on outcrossing (by 6.6%).

Traits that acted during the middle or later stages of the lifecycle showed significantly more positive responses to outbreeding compared with early acting traits (pMCMC = 0.006 and 0.004 respectively). The absolute outbreeding response in late-acting traits was also significantly greater than zero (the mid-parent phenotype; Figure 4e).

F1 hybrids experienced a (non-significant) benefit to outbreeding (3.7% benefit in phenotype relative to the mid-parent value; pMCMC = 0.064;). In the F2, hybrids experienced a significantly lower phenotypic response to outbreeding than F1 hybrids (Figure 4b; pMCMC < 0.001; Additional file 1: Table S9). F2 and F3 hybrids experienced a net cost to outbreeding (−4.7% and −15.9%), but these responses were not consistently different from the mid-parent phenotype (Figure 4b). Results for the F3 generation were supported by only a very small number of articles and effect sizes.

There was little evidence that outbreeding responses were explained by high-level taxonomy. Only mammals showed outbreeding responses that differed significantly from parent phenotypes (pMCMC = 0.01; Figure 4f), and this taxonomic group was represented by data from only four articles.

The association of physical distance with outbreeding responses was very small, and not significantly different from zero (−0.5% phenotypic change for each log unit of distance; pMCMC = 0.368). Only ~80% of articles reported useable data on physical distance.

Observation environment was not a consistent predictor of the outbreeding response. However, we found that phenotypic responses to outbreeding observed in lab environments were of consistently lower magnitude than those observed in natural populations or habitats (Figure 4k; pMCMC = 0.002; Additional file 1: Table S9). Neither population status, nor study quality score were consistent predictors of outbreeding responses (Figure 4; Table 6).

Meta-analysis with multiple explanatory variables

We used a model reduction approach to determine the set of explanatory variables that best predicted the data. The best-fitting minimal model contained only the trait type predictor (Figure 4d; Additional file 1: Tables S10 & S11).

Figure 6 shows outbreeding responses for different fitness classes (representing trait type; fitness components or not) in different generations. We could not fit a model including an interaction between trait type and generation because some trait types contained data from only one generation. F1 fitness component traits showed little response to outbreeding (+1.3% relative to parent lineages; Figure 6). However, fitness component traits showed a significantly negative response to outbreeding in the F2 (−8.8%). The remaining non-fitness component traits showed a consistently positive response to outbreeding during the F1 (+6.9%), and also a positive response during the F2 (+3.5%; Figure 6).

Fitness class (fitness component or remaining trait types) and generation (F1 or F2) predict variation in outbreeding responses. Fitness components were defined as viability, survival, fecundity traits or integrated/ multiplicative measures of fitness. Posterior means and credible intervals were estimated by fitting a fitness class × generation interaction. X-axis scale, point estimates, error bars and abbreviations as in Figure 4.

Heterogeneity in outbreeding responses

The study variance component (describing heterogeneity in outbreeding response among studies) was 0.0145 in the minimal model (Table 6), and accounted for 39.5% of total heterogeneity in outbreeding responses. The within-study (between effect size) variance accounted for 27.1% of heterogeneity. The remaining heterogeneity (33.4%) was attributable to measurement error variance (variation within effect sizes).

Discussion

In this review we have shown that hybrids arising from intraspecific outbreeding express phenotypes that do not differ from those expected given parent phenotypes (+2.6% phenotypic change; pMCMC = 0.156). However, we also identified predictors with which outbreeding responses were associated significantly, and heterogeneity in responses among studies.

Reasons for heterogeneity

There was significant heterogeneity in outbreeding responses among studies. This among-study variation in outbreeding responses could be due to species-specific or population-specific effects, or other study-specific contexts. In other words, part of this heterogeneity may be attributable to unmeasured, but biologically significant case-specific variables. These might include population demographic history and isolation, genetic architecture and differential adaptation between hybridising populations [17, 21]. This study-level contextual variation must be taken into account when interpreting the relationships between explanatory variables and outbreeding responses described in this review.

We found that trait type explained variation in outbreeding responses, and was the single best predictor of these responses. Fitness components (especially survival and viability) had consistently lower outbreeding responses than other traits. In the only other meta-analysis on outbreeding responses [16], McClelland and Naish found that overall positive responses to outbreeding in fish species were driven largely by the responses of morphological traits. This observation is consistent with our result that non-fitness traits show a significantly more positive response to outbreeding than fitness component traits. Our result implies that the traits most important in regulating population size, growth rate and persistence may be those affected most negatively by outbreeding. In animals, fitness traits are also those influenced most strongly by inbreeding depression [135]. This effect is thought to be driven by differences in the extent of dominance variance between fitness and other traits, or in the average directionality of dominance interactions [135]. However, these arguments cannot be extended easily to explain our result. In fact, they lead to the expectation that fitness traits should respond more positively to outbreeding than other traits, at least where the source populations are inbred. We suggest that our result implies that fitness component traits are underpinned to a greater extent by epistatic interactions among loci than is the case for other traits. This suggestion is consistent with the observation that fitness is less heritable than other traits, and the idea that this lower heritability is associated with a greater non-additive component to the phenotype (reviewed in [136]). More broadly, this finding suggests that it may be unrealistic to understand fitness responses to outbreeding by considering only extrinsic outbreeding effects (i.e. taking into account only additive genetic variation).

We found that hybrid generation was also significantly associated with phenotypic responses to outbreeding. Specifically, there was a cost to outbreeding in the F2 and F3 relative to the F1. This shift in the hybrid outbreeding response over generations is expected from theory [17]. Between-population outbreeding creates between-population heterozygosity across the genome in the F1. This process can mask the expression of deleterious alleles that have drifted to high frequency in either of the parent populations, resulting in an improved hybrid phenotype (and potentially greater fitness, i.e. heterosis) relative to either parent population. In the F2 generation segregation reduces the between-source heterozygosity by half, while recombination breaks up favourable epistasis present in either source population. Thus we expect a decrease in the expected phenotype in F2 compared with F1 individuals. From a conservation perspective, the crucial question is whether the absolute fitness of F2 or later generation hybrids is lower or greater than the mid-parent value. If the hybrids are less fit than their parents (outbreeding depression), then there has been a true cost to hybridisation, and this may compromise conservation plans that result in population admixture and hybridisation. Our observation that F2 individuals have decreased phenotypic performance relative to F1 individuals is consistent with the synthesis presented by Edmands [15]. However, in their meta-analysis, McClelland and Naish found positive responses to outbreeding (relative to parental lineages) in both the F1 and F2 [16]. This result runs counter to our observation. We suggest that the difference arose because we were able to control for between-study variation in outbreeding responses, by fitting study-level random effects, allowing a more sensitive comparison of F1 and F2 responses. However it may be that McClelland and Naish’s inclusion of outbreeding between species, inclusion of outbreeding between farmed lineages, or focus on fish could also explain the difference in outcomes.

A breakdown of trait responses by generation indicated approximate parity of F1 fitness with the mid-parent phenotype (Figure 6). Other (non-fitness component) traits showed a consistent expected benefit following outbreeding during the F1. During the F2, fitness components suffered a significant net cost relative to parent fitness. These results suggest that there may be absolute fitness costs to outbreeding in the F2 (outbreeding depression). However, we must be cautious about this suggestion for two reasons. First, there were only 22 studies with observations on F2 hybrid performance. Second, we do not know whether these 22 studies made observations using species and population pairs that are representative of all possible intraspecific outbreeding contexts. The effects in Figure 6 strengthen our argument that epistasis has a relatively greater role in underpinning fitness component traits. We observed overall outbreeding depression (fitness costs) in the F2, but no such F2 costs in traits that were not fitness components. The former result is highly suggestive of a role for epistasis, whereas the generational shift in hybrid phenotype for non-fitness component traits may be consistent with the loss of between-source heterozygosity [17].

Outbreeding responses for early acting traits were significantly lower than those for mid- and late-acting traits. It is possible that this result was caused by maternal effects, such that F1 phenotypes are a function of maternal parent phenotypes, and F2 phenotypes are a function of maternal F1 phenotypes [24, 137]. This response to the maternal environment during outbreeding can result in F2 phenotypes exceeding F1 phenotypes. Early acting traits showed an F2 decline in phenotype (relative to F1) closely similar to that of mid and late acting traits (Additional file 1: Figure S12). These results indicate that maternal effects may be weak relative to the effects of the decline of between-source heterozygosity in the F2, or the break-up of internal co-adaptation. Most (86.6%) of the effect sizes for early acting traits were viability traits (early survival). Outbreeding responses for these traits did not differ significantly from those of other (mid and late acting) survival traits. Thus, an alternative explanation for the more negative outbreeding responses observed in early acting traits may be that they were (almost all) survival traits.

The genetic divergence that underpins outbreeding responses depends in part on the extent of demographic connectivity between the populations by migration. We did not record migration rates per se, although we did record physical distance between crossed populations, as a proxy for this. We detected only very limited (and non-significant) variation in the outbreeding response with physical distance. This may be because physical distance scales differently with dispersal ability (and hence potential connectivity) for each species. Alternatively, there may be no relationship, or a non-linear relationship between outbreeding responses and physical separation of inter-mating populations.

Review limitations

Review scope

The scope of our systematic review was limited to intraspecific, post-zygotic outbreeding effects that involved at least one natural population, and excluded taxonomically complex outbreeding contexts. Thus, we cannot generalise our results to comment on taxonomically complex situations (hybrid swarms and speciation complexes), outbreeding between species, outbreeding exclusively between farmed populations, agricultural or horticultural cultivars or strains, or pre-zygotic outbreeding barriers.

Our effect size was a measure of intrinsic outbreeding responses [15, 18], i.e. the deviation of hybrid phenotype from the mid-parent phenotype. Thus we cannot use our results to comment on the extent or magnitude of extrinsic responses to outbreeding (deviations in hybrid performance from either of the parents, due to additive gene effects).

Where populations mix under natural (uncontrolled) conditions, a broader range of crosses would be produced than the set of hybrid types that we considered. For example F1 hybrids could backcross with individuals that have a pure parental ancestry. Progeny of backcrosses between F1 and parental lineages are expected to possess between-source heterozygosity equivalent to F2 and later generation hybrids but with a reduced epistatic cost [17]. Thus, backcrossing may allow beneficial alleles to escape deleterious hybrid genetic backgrounds, and introgress into populations that have received managed immigration. However, where internal co-adaptation is between nuclear and cytoplasmic genomes, backcrossing may restore epistatic fitness loss only in one backcross direction [50].

Sources of bias

Visual inspection of funnel plots and a test of funnel plot asymmetry indicated little evidence for publication bias (either towards phenotypic outbreeding costs, or towards outbreeding benefits). Identification of publication bias from funnel plots may be prone to error in smaller meta-analyses (e.g. containing ~ 10 studies; [138]), but our data were based on 98 studies, and should be less sensitive to this issue of sample size. Bias would have most effect on our results and conclusions if any studies not included in our review (e.g. unpublished work, sources of grey literature that we did not consider) reported outbreeding responses that differed systematically from those in the studies that we did include. However, outbreeding responses may be biased in either of two directions: towards fitness costs (outbreeding depression), or towards fitness gains (heterosis), depending on assumptions made by the researcher. Thus, it is not obvious that any bias in outbreeding responses should influence our meta-analyses systematically.

The nested structure of our meta-analytic model precluded an assessment of the sensitivity of the results to the “file drawer problem” by traditional routes, e.g. by quantifying the number of missing non-significant studies required to make the observed pooled effect sizes non-significant (“fail-safe n”; [139]). The value of calculating a fail-safe n for the significance of fixed effects within our models could, in any case, be called into question, given the study-level heterogeneity in outbreeding responses.

Limitations of the primary research literature

We found relatively few studies that followed later generation responses to outbreeding (F3 and later hybrid generations). Thus the available evidence provides a poor basis for understanding the longer-term consequences of intraspecific outbreeding (i.e. the outbreeding responses of greatest potential interest to conservation practitioners). Only 20.4% of articles included in our review observed outbreeding responses within natural populations. This represents a shortcoming of the literature, given that the effects of outbreeding may differ between natural and lab environments (Figure 4k). Wherever possible, investigators should seek to conduct studies on phenotypic outbreeding effects either in natural populations or habitat, or under conditions that approximate as far as possible those within natural populations. Many articles also lacked clarity with regard to their crossing designs, their level of replication (attempted and realised), and to what hierarchical level in the sampling design measurement error referred (e.g. individual level, family level, treatment level).

Review conclusions

Implications for managing between-population outbreeding

The available evidence has implications for several sorts of conservation measures that result in between-population outbreeding. These measures include “range restoration”, where individuals are translocated (re-introduced) within the existing native range of a species [140, 141], “reinforcement” where individuals are translocated to a particular population that is in decline, in order to bolster that population demographically [141, 142], and assisted migration e.g. [143], in cases where the translocated individuals come from multiple source populations. The conservation practitioner is interested in whether between-population outbreeding influences the outcome of these conservation measures, increasing or decreasing population growth or viability. The results of this review do not relate directly to the effect of outbreeding on demographic sustainability. However, our review contributes to this understanding by synthesising the effects of outbreeding on phenotypes of hybrid offspring relative to parent lineages. These phenotypes, including fitness components, are expected to contribute to the growth and viability of populations.

The available evidence indicates that between-population outbreeding may lead to phenotypic benefits in the F1, but could also lead to absolute costs to fitness in the F2 and later generations (the latter result is based on 18 studies; Figure 6). However, not all outbreeding will lead to outbreeding depression in the F2 generation. This is evident if we consider the study-level heterogeneity in outbreeding responses, which imply scatter in outbreeding responses around the typical F2 fitness response. In addition, there are good reasons for supposing that outbreeding depression may be more likely for some population pairs than for others. Previous studies have suggested that outbreeding depression is likely when outbreeding populations have been isolated for many generations (especially if they occupy divergent environments), are genetically divergent or are differentiated in chromosome structure or number [21, 26]. These factors influence (or are measures of) the underlying basis of outbreeding depression, i.e. adaptive differentiation, and internal (epistatic) co-adaptation within the genome. Therefore, the available evidence suggests that conservation practitioners should avoid mixing population pairs that meet these conditions, since there is an enhanced risk that their admixture would lead to outbreeding depression [21]. Frankham et al. [21] give specific guidelines and a decision making tool to assist in identifying population pairs whose mixture may risk outbreeding depression.

Implications for research

The heterogeneity in outbreeding responses we observed among studies suggests that future research should strive to document as carefully and as fully as possible the factors that may lead to this variation. These could include the level of demographic isolation (present and historical) that a population has been exposed to, generation time, effective population size, the extent of cytogenetic differences between crossing populations, and the degree of environmental differentiation between hybridising populations (relative to other populations in a species’ range). This would allow future reviews to model this heterogeneity and to begin to understand the causes of between-species and between-population differences in outbreeding responses. In addition, researchers should aim to observe hybrid offspring and parental lineages in environments that are as close to natural as possible. More generally, other aspects of study design that improve the internal and external validity of line-cross analyses and investigations into phenotypic outbreeding responses (Table 3) should be incorporated into future studies. For example, we suggest that prospective authors of outbreeding studies should aim to follow the fitness effects of between-population outbreeding into at least the F2 generation, and ideally to incorporate non-inbred backcrosses into their designs as well. Where resources allow, researchers should carry out control crosses within parental populations (e.g. F1, F2 etc. within population controls) as the gold standard for comparison with hybrid offspring. Ideally, researchers would also follow non-outbred crosses within both parent populations as comparators for hybrid performance. Wherever possible, investigators should measure total fitness rather than individual components of fitness (i.e. the contribution to future generations resulting from the aggregate effects of survival and reproduction). These improvements to study design should yield a clearer view of the conditions under which either heterosis, or outbreeding depression may occur following between-population outcrossing.

Author’s contributions

RW lead the literature survey and assessment, carried out the data extraction, designed and carried out the statistical analysis and drafted the review report. All authors contributed to the design and focus of the study. ASP and GBS implemented the systematic review methodology as specifically employed in this review. GBS participated in literature searches, and contributed to the design of the statistical analysis. TB conceived of the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

Frankel OH: Genetic conservation: our evolutionary responsibility. Genetics 1974, 78: 53–65.

Frankel OH, Soulé ME: Conservation and evolution. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1981.

Crnokrak P, Roff DA: Inbreeding depression in the wild. Heredity 1999, 83: 260–270. 10.1038/sj.hdy.6885530

Keller LF, Waller DM: Inbreeding effects in wild populations. Trends Ecol Evol 2002, 17: 230–241. 10.1016/S0169-5347(02)02489-8

O'Grady JJ, Brook BW, Reed DH, Ballou JD, Tonkyn DW, Frankham R: Realistic levels of inbreeding depression strongly affect extinction risk in wild populations. Biol Conserv 2006, 133: 42–51. 10.1016/j.biocon.2006.05.016

Reed DH, Frankham R: Correlation between fitness and genetic diversity. Conserv Biol 2003, 17: 230–237. 10.1046/j.1523-1739.2003.01236.x

Hedrick PW, Fredrickson R: Genetic rescue guidelines with examples from Mexican wolves and Florida panthers. Conserv Genet 2010, 11: 615–626. 10.1007/s10592-009-9999-5

Tallmon DA, Luikart G, Waples RS: The alluring simplicity and complex reality of genetic rescue. Trends Ecol Evol 2004, 19: 489–496. 10.1016/j.tree.2004.07.003

Westemeier RL, Brawn JD, Simpson SA, Esker TL, Jansen RW, Walk JW, Kershner EL, Bouzat JL, Paige KN: Tracking the long-term decline and recovery of an isolated population. Science 1998, 282: 1695–1698.

Hogg JT, Forbes SH, Steele BM, Luikart G: Genetic rescue of an insular population of large mammals. Proc R Soc Lond, Ser B: Biol Sci 2006, 273: 1491–1499. 10.1098/rspb.2006.3477

Madsen T, Shine R, Olsson M, Wittzell H: Restoration of an inbred adder population. Nature 1999, 402: 34–35. 10.1038/46941

Trinkel M, Ferguson N, Reid A, Reid C, Somers M, Turelli L, Graf J, Szykman M, Cooper D, Haverman P, et al.: Translocating lions into an inbred lion population in the Hluhluwe–iMfolozi Park, South Africa. Anim Conserv 2008, 11: 138–143. 10.1111/j.1469-1795.2008.00163.x

Vilà C, Sundqvist A, Flagstad Ø, Seddon J, Björnerfeldt S, Kojola I, Casulli A, Sand H, Wabakken P, Ellegren H: Rescue of a severely bottlenecked wolf ( Canis lupus ) population by a single immigrant. Proc Roy Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2003, 270: 91–97. 10.1098/rspb.2002.2184

Gregory A, Burke T, Ferris R, Robson J, Smithers R, Whitlock R: The conservation of genetic diversity: science and policy needs in a changing world. Peterborough, UK; 2006.

Edmands S: Between a rock and a hard place: evaluating the relative risks of inbreeding and outbreeding for conservation and management. Mol Ecol 2007, 16: 463–475.

McClelland EK, Naish KA: What is the fitness outcome of crossing unrelated fish populations? A meta-analysis and an evaluation of future research directions. Conserv Genet 2007, 8: 397–416. 10.1007/s10592-006-9178-x

Lynch M: The genetic interpretation of inbreeding depression and outbreeding depression. Evolution 1991, 45: 622–629. 10.2307/2409915

Allendorf FW, Leary RF, Spruell P, Wenburg JK: The problems with hybrids: setting conservation guidelines. Trends Ecol Evol 2001, 16: 613–622. 10.1016/S0169-5347(01)02290-X

Rieseberg LH: Chromosomal rearrangements and speciation. Trends Ecol Evol 2001, 16: 351–358. 10.1016/S0169-5347(01)02187-5

White MJD: Modes of speciation. San Francisco, California: W. H. Freeman; 1978.

Frankham R, Ballou JD, Eldridge MDB, Lacy RC, Ralls K, Dudash MR, Fenster CB: Predicting the probability of outbreeding depression. Conserv Biol 2011, 25: 465–475. 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2011.01662.x

Arnold ML, Hodges SA: Are natural hybrids fit or unfit relative to their parents? Trends Ecol Evol 1995, 10: 67–71. 10.1016/S0169-5347(00)88979-X

Coyne JA, Orr HA: Speciation. Sunderland, MA, USA: Sinauer Associates; 2004.

Falconer DS, Mackay TFC: Quantitative Genetics. Harlow, England: Prentice Hall; 1996.

Orr HA: The population genetics of speciation: the evolution of hybrid incompatibilities. Genetics 1995, 139: 1805–1813.

Edmands S, Timmerman CC: Modeling factors affecting the severity of outbreeding depression. Conserv Biol 2003, 17: 883–892. 10.1046/j.1523-1739.2003.02026.x

Edmands S: Does parental divergence predict reproductive compatibility. Trends Ecol Evol 2002, 17: 520–527. 10.1016/S0169-5347(02)02585-5

Storfer A: Gene flow and endangered species translocations: a topic revisited. Biol Conserv 1999, 87: 173–180. 10.1016/S0006-3207(98)00066-4

Whitlock R, Stewart GB, Pullin AS, Goodman SJ, Piertney SB, Butlin RK, Burke T, Brodie J, Hipperson H: Does translocation of individuals between populations result in net cost to fitness in offspring of mixed populations?. Bangor, UK: Collaboration for Environmental Evidence; 2009.

Hedrick PW: Evaluation of D2, a microsatellite measure of inbreeding and outbreeding, in wolves with a known pedigree. Evolution 2001, 55: 1256–1260.

Cohen J: A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ Psychol Meas 1960, 20: 37–46. 10.1177/001316446002000104

Pullin AS, Stewart GB: Guidelines for systematic review in conservation and environmental management. Conserv Biol 2006, 20: 1647–1656. 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2006.00485.x

Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR: Introduction to meta-analysis. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2009.

Hadfield JD: MCMC methods for multi-response generalized linear mixed models: the MCMCglmm R package. J Stat Softw 2010, 33: 1–22.

Hadfield JD, Nakagawa S: General quantitative genetic methods for comparative biology: phylogenies, taxonomies and multi-trait models for continuous and categorical characters. J Evol Biol 2010, 23: 494–508. 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2009.01915.x

Gelman A: Prior distributions for variance parameters in hierarchical models. Bayesian Analysis 2006, 1: 515–533.

Spiegelhalter DJ, Best NG, Carlin BP, van der Linde A: Bayesian measures of model complexity and fit. J R Stat Soc Lond B 2002, 64: 583–639. 10.1111/1467-9868.00353

Sutton JT, Nakagawa S, Robertson BC, Jamieson IG: Disentangling the roles of natural selection and genetic drift in shaping variation at MHC immunity genes. Mol Ecol 2011, 20: 4408–4420. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05292.x

Higgins JPT, Thompson SG: Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 2002, 21: 1539–1558. 10.1002/sim.1186

Viechtbauer W: Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J Stat Softw 2010, 36: 1–48.

Egger M, Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C: Bias in metaanalysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Br Med J 1997, 315: 629–634. 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629

Gelman A, Carlin JB, Stern HS, Rubin DB: Bayesian Data Analysis. London, New York, Washington, D. C.: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2004.

Landis JR, Koch GG: The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977, 33: 159–174. 10.2307/2529310

Sherman CDH, Wapstra E, Uller T, Olsson M: Male and female effects on fertilization success and offspring viability in the Peron's tree frog, Litoria peronii . Austral Ecol 2008, 33: 348–352. 10.1111/j.1442-9993.2007.01823.x

Sagvik J, Uller T, Olsson M: Outbreeding depression in the common frog, Rana temporaria . Conserv Genet 2005, 6: 205–211. 10.1007/s10592-004-7829-3

Byrom AE, Burns CW, Wallis GP: Experimental hybridization of alpine and lowland forms of Boeckella dilata , a calanoid copepod. Heredity 1993, 71: 508–515. 10.1038/hdy.1993.169

Edmands S, Feaman HV, Harrison JS, Timmerman CC: Genetic consequences of many generations of hybridization between divergent copepod populations. J Hered 2005, 96: 114–123. 10.1093/jhered/esi014

Edmands S, Deimler JK: Local adaptation, intrinsic coadaptation and the effects of environmental stress on interpopulation hybrids in the copepod Tigriopus californicus . J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 2004, 303: 183–196. 10.1016/j.jembe.2003.11.012

Edmands S: Heterosis and outbreeding depression in interpopulation crosses spanning a wide range of divergence. Evolution 1999, 53: 1757–1768. 10.2307/2640438

Ellison CK, Burton RS: Interpopulation hybrid breakdown maps to the mitochondrial genome. Evolution 2008, 62: 631–638. 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2007.00305.x

Leberg PL: Strategies for population reintroduction - effects of genetic-variability on population growth and size. Conserv Biol 1993, 7: 194–199. 10.1046/j.1523-1739.1993.07010194.x

Nguenga D, Teugels GG, Ollevier F: Fertilization, hatching, survival and growth rates in reciprocal crosses of two strains of an African catfish Heterobranchus longifilis Valenciennes 1840 under controlled hatchery conditions. Aquacult Res 2000, 31: 565–573. 10.1046/j.1365-2109.2000.00468.x

Gjerde B, Reddy P, Mahapatra KD, Saha JN, Jana RK, Meher PK, Sahoo M, Lenka S, Govindassamy P, Rye M: Growth and survival in two complete diallele crosses with five stocks of Rohu carp ( Labeo rohita ). Aquaculture 2002, 209: 103–115. 10.1016/S0044-8486(01)00848-1

Cooke SJ, Philipp DP: Influence of local adaptation and interstock hybridization on the cardiovascular performance of largemouth bass Micropterus salmoides . J Exp Biol 2005, 208: 2055–2062. 10.1242/jeb.01602

Cooke SJ, Kassler TW, Phillipp DP: Physiological performance of largemouth bass related to local adaptation and interstock hybridization: implications for conservation and management. J Fish Biol 2001, 59: 248–268. 10.1111/j.1095-8649.2001.tb01389.x

Goldberg TL, Grant EC, Inendino KR, Kassler TW, Claussen JE, Philipp DP: Increased infectious disease susceptibility resulting from outbreeding depression. Conserv Biol 2005, 19: 455–462. 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2005.00091.x

Gharrett AJ, Smoker WW, Reisenbichler RR, Taylor SG: Outbreeding depression in hybrids between odd- and even-broodyear pink salmon. Aquaculture 1999, 173: 117–129. 10.1016/S0044-8486(98)00480-3

Gharrett AJ, Smoker WW: Two generations of hybrids between even-year and odd-year pink salmon Oncorhynchus gorbuscha a test for outbreeding depression. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 1991, 48: 1744–1749. 10.1139/f91-206

Gilk SE, Wang IA, Hoover CL, Smoker WW, Taylor SG, Gray AK, Gharrett AJ: Outbreeding depression in hybrids between spatially separated pink salmon, Oncorhynchus gorbuscha , populations: marine survival, homing ability, and variability in family size. Environ Biol Fishes 2004, 69: 287–297.

Johnsson JI, Clarke WC, Withler RE: Hybridization with domesticated rainbow trout ( Oncorhynchus mykiss ) reduces seasonal variation in growth of steelhead trout ( O. mykiss ). Can J Fish Aquat Sci 1993, 50: 480–487. 10.1139/f93-056

Miller LM, Close T, Kapuscinski AR: Lower fitness of hatchery and hybrid rainbow trout compared to naturalized populations in Lake Superior tributaries. Mol Ecol 2004, 13: 3379–3388. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2004.02347.x

Tymchuk WE, Sundström LF, Devlin RH: Growth and survival trade-offs and outbreeding depression in rainbow trout ( Oncorhynchus mykiss ). Evolution 2007, 61: 1225–1237. 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2007.00102.x

Bryden CA, Heath JW, Heath DD: Performance and heterosis in farmed and wild Chinook salmon ( Oncorhynchus tshawyacha ) hybrid and purebred crosses. Aquaculture 2004, 235: 249–261. 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2004.01.027

Sheffer RJ, Hedrick PW, Velasco AL: Testing for inbreeding and outbreeding depression in the endangered Gila topminnow. Anim Conserv 1999, 2: 121–129. 10.1111/j.1469-1795.1999.tb00057.x

Fraser DJ, Houde ALS, Debes PV, O'Reilly P, Eddington JD, Hutchings JA: Consequences of farmed-wild hybridization across divergent wild populations and multiple traits in salmon. Ecol Appl 2010, 20: 935–953. 10.1890/09-0694.1

Fraser DJ, Cook AM, Eddington JD, Bentzen P, Hutchings JA: Mixed evidence for reduced local adaptation in wild salmon resulting from interbreeding with escaped farmed salmon: complexities in hybrid fitness. Evolutionary Applications 2008, 1: 501–512. 10.1111/j.1752-4571.2008.00037.x

Houde ALS, Fraser DJ, Hutchings JA: Reduced anti-predator responses in multi-generational hybrids of farmed and wild Atlantic salmon ( Salmo salar L.). Conserv Genet 2010, 11: 785–794. 10.1007/s10592-009-9892-2

McGinnity P, Prodohl P, Ferguson A, Hynes R, Maoileidigh NO, Baker N, Cotter D, O'Hea B, Cooke D, Rogan G, et al.: Fitness reduction and potential extinction of wild populations of Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar , as a result of interactions with escaped farm salmon. Proc R Soc B-Biol Sci 2003, 270: 2443–2450. 10.1098/rspb.2003.2520

Dahl J, Pettersson E, Dannewitz J, Järvi T, Löf AC: No difference in survival, growth and morphology between offspring of wild-born, hatchery and hybrid brown trout ( Salmo trutta ). Ecol Freshwat Fish 2006, 15: 388–397. 10.1111/j.1600-0633.2006.00150.x

Nilsson J: Arctic charr strain crosses - effects on growth and sexual maturity. J Fish Biol 1993, 43: 163–171. 10.1111/j.1095-8649.1993.tb00420.x

Escobar JS, Nicot A, David P: The different sources of variation in inbreeding depression, heterosis and outbreeding depression in a metapopulation of Physa acuta . Genetics 2008, 180: 1593–1608. 10.1534/genetics.108.092718

McCarthy TM, Sih A: Relatedness of mates influences mating behaviour and reproductive success of the hermaphroditic freshwater snail Physa gyrina . Evol Ecol Res 2008, 10: 77–94.

Reinhardt K, Kohler G: Conservation of the red-winged grasshopper, Oedipoda germanica (Latr.): the influence of reproductive behaviour. Biol Conserv 2002, 107: 221–228. 10.1016/S0006-3207(02)00096-4

Hogg JT, Forbes SH, Steele BM, Luikart G: Genetic rescue of an insular population of large mammals. Proc R Soc B-Biol Sci 2006, 273: 1491–1499. 10.1098/rspb.2006.3477

Keane B: Dispersal and inbreeding avoidance in the white-footed mouse Peromyscus leucopus . Anim Behav 1990, 40: 143–152. 10.1016/S0003-3472(05)80674-8

Cruz P, Ramirez JL, Garcia GA, Ibarra AM: Genetic differences between two populations of catarina scallop ( Argopecten ventricosus ) for adaptations for growth and survival in a stressful environment. Aquaculture 1998, 166: 321–335. 10.1016/S0044-8486(98)00285-3

Cruz P, Ibarra AM: Larval growth and survival of two catarina scallop ( Argopecten circularis , Sowerby, 1835) populations and their reciprocal crosses. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 1997, 212: 95–110. 10.1016/S0022-0981(96)02742-6

Dolgin ES, Felix MA, Cutter AD: Hakuna Nematoda: genetic and phenotypic diversity in African isolates of Caenorhabditis elegans and C. briggsae . Heredity 2008, 100: 304–315. 10.1038/sj.hdy.6801079

Keller M, Kollmann J, Edwards PJ: Genetic introgression from distant provenances reduces fitness in local weed populations. J Appl Ecol 2000, 37: 647–659. 10.1046/j.1365-2664.2000.00517.x

Andalo C, Cruzan MB, Cazettes C, Pujol B, Burrus M, Thébaud C: Post-pollination barriers do not explain the persistence of two distinct Antirrhinum subspecies with parapatric distribution. Plant Syst Evol 2010, 286: 223–234. 10.1007/s00606-010-0303-4

Luijten SH, Kery M, Oostermeijer JGB, Den Nijs HJCM: Demographic consequences of inbreeding and outbreeding in Arnica montana: a field experiment. J Ecol 2002, 90: 593–603. 10.1046/j.1365-2745.2002.00703.x

Raabová J, Münzbergová Z, Fischer M: Consequences of near and far between-population crosses for offspring fitness in a rare herb. Plant Biol 2009, 11: 829–836. 10.1111/j.1438-8677.2008.00186.x

Johansen-Morris AD, Latta RG: Fitness consequences of hybridization between ecotypes of Avena barbata: hybrid breakdown, hybrid vigor, and transgressive segregation. Evolution 2006, 60: 1585–1595.

Rao GY, Andersson S, Widen B: Developmental stability in Brassica cretica: the effect of crossing distance on fluctuating asymmetry in cotyledon morphology. Heredity 2002, 88: 197–202. 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800027

Heiser DA, Shaw RG: The fitness effects of outcrossing in Calylophus serrulatus , a permanent translocation heterozygote. Evolution 2006, 60: 64–76.

Etterson JR, Keller SR, Galloway LF: Epistatic and cytonuclear interactions govern outbreeding depression in the autotetraploid Campanulastrum americanum . Evolution 2007, 61: 2671–2683. 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2007.00234.x

Galloway LF, Etterson JR: Population differentiation and hybrid success in Campanula americana: geography and genome size. J Evol Biol 2005, 18: 81–89. 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2004.00801.x

Kaye TN, Lawrence B: Fitness effects of inbreeding and outbreeding on golden paintbrush (Castilleja levisecta): implications for recovery and reintroduction. Corvallis, Oregon: Institute for Applied Ecology; 2003.

Erickson DL, Fenster CB: Intraspecific hybridization and the recovery of fitness in the native legume Chamaecrista fasciculata . Evolution 2006, 60: 225–233.

Holtsford TP: Variation in inbreeding depression among families and populations of Clarkia tembloriensis (Onagraceae). Heredity 1996, 76: 83–91. 10.1038/hdy.1996.11

Paschke M, Abs C, Schmid B: Effects of population size and pollen diversity on reproductive success and offspring size in the narrow endemic Cochlearia bavarica (Brassicaceae). Am J Bot 2002, 89: 1250–1259. 10.3732/ajb.89.8.1250

Pelabon C, Carlson ML, Hansen TF, Armbruster WS: Effects of crossing distance on offspring fitness and developmental stability in Dalechampia scandens (Euphorbiaceae). Am J Bot 2005, 92: 842–851. 10.3732/ajb.92.5.842

Waser NM, Price MV: Crossing-distance effects in Delphinium nelsonii: outbreeding and inbreeding depression in progeny fitness. Evolution 1994, 48: 842–852. 10.2307/2410491

Grindeland JM: Inbreeding depression and outbreeding depression in Digitalis purpurea: optimal outcrossing distance in a tetraploid. J Evol Biol 2008, 21: 716–726. 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2008.01519.x

Wagenius S, Hangelbroek HH, Ridley CE, Shaw RG: Biparental inbreeding and interremnant mating in a perennial prairie plant: fitness consequences for progeny in their first eight years. Evolution 2010, 64: 761–771. 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00860.x

Sobrevila C: Effects of distance between pollen donor and pollen recipient on fitness components in Espeletia schultzii . Am J Bot 1988, 75: 701–724. 10.2307/2444203

Hardner CM, Potts BM, Gore PL: The relationship between cross success and spatial proximity of Eucalyptus globulus ssp. globulus parents. Evolution 1998, 52: 614–618. 10.2307/2411096

Byers DL: Effect of cross proximity on progeny fitness in a rare and a common species of Eupatorium (Asteraceae). Am J Bot 1998, 85: 644–653. 10.2307/2446533

Oostermeijer JGB, Altenburg RGM, Den Nijs HCM: Effects of outcrossing distance and selfing on fitness components in the rare Gentiana pneumonanthe (Gentianaceae). Acta Bot Neerl 1995, 44: 257–268.

Fischer M, Matthies D: Mating structure and inbreeding and outbreeding depression in the rare plant Gentianella germanica (Gentianaceae). Am J Bot 1997, 84: 1685–1692. 10.2307/2446466

Paland S, Schmid B: Population size and the nature of genetic load in Gentianella germanica . Evolution 2003, 57: 2242–2251.

Vandepitte K, Honnay O, Jacquemyn H, Roldán-Ruiz I: Effects of outcrossing in fragmented populations of the primarily selfing forest herb Geum urbanum . Evol Ecol 2010, 24: 1353–1364. 10.1007/s10682-010-9395-0

Ellis JR, McCauley DE: Phenotypic differentiation in fitness related traits between populations of an extremely rare sunflower: conservation management of isolated populations. Biol Conserv 2009, 142: 1836–1843. 10.1016/j.biocon.2009.03.029

Becker U, Reinhold T, Matthies D: Effects of pollination distance on reproduction and offspring performance in Hypochoeris radicata: experiments with plants from three European regions. Biol Conserv 2006, 132: 109–118. 10.1016/j.biocon.2006.03.018

Waser NM, Price MV: Optimal outcrossing in Ipomopsis aggregata seed set and offspring fitness. Evolution 1989, 43: 1097–1109. 10.2307/2409589

Schlichting CD, Devlin B: Pollen and ovule sources affect seed production of Lobelia cardinalis (Lobeliaceae). Am J Bot 1992, 79: 891–898. 10.2307/2444999

Mutikainen P, Delph LF: Inbreeding depression in gynodioecious Lobelia siphilitica: among-family differences override between-morph differences. Evolution 1998, 52: 1572–1582. 10.2307/2411331

Montalvo AM, Ellstrand NC: Nonlocal transplantation and outbreeding depression in the subshrub Lotus scoparius (Fabaceae). Am J Bot 2001, 88: 258–269. 10.2307/2657017

Hauser TP, Loeschcke V: Inbreeding depression and mating-distance dependent offspring fitness in large and small populations of Lychnis flos-cuculi (Caryophyllaceae). J Evol Biol 1994, 7: 609–622. 10.1046/j.1420-9101.1994.7050609.x

Leimu R, Fischer M: Between-population outbreeding affects plant defence. PLoS One 2010., 5:

Pisanu PC, Gross CL, Flood L: Reproduction in wild populations of the threatened tree Macadamia tetraphylla: interpopulation pollen enriches fecundity in a declining species. Biotropica 2009, 41: 391–398. 10.1111/j.1744-7429.2008.00484.x

Vandepitte K, Roldán-Ruiz I, Honnay O: Reproductive consequences of mate quantity versus mate diversity in a wind-pollinated plant. Acta Oecol 2009, 35: 548–553. 10.1016/j.actao.2009.04.004

Mooney EH, McGraw JB: Effects of self-pollination and outcrossing with cultivated plants in small natural populations of American ginseng, Panax quinquefolius (Araliaceae). Am J Bot 2007, 94: 1677–1687. 10.3732/ajb.94.10.1677

Levin DA, Bulinska-Radomska Z: Effects of hybridization and inbreeding on fitness in Phlox . Am J Bot 1988, 75: 1632–1639. 10.2307/2444679