Abstract

Background

C-reactive protein (CRP) is positively associated with risk for cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality. Some but not all randomized and non-randomized clinical trials found significant associations between fenofibrate therapy and CRP but the direction and magnitude of the association varied across studies. The duration of treatment, patient populations and sample sizes varied greatly, and most short-term studies (i.e., ≤ 12 weeks) had fewer than 50 patients. In this study we meta-analyzed randomized clinical trials to determine the short-term effect of fenofibrate on CRP.

Methods

Two reviewers independently searched PubMed and other online databases for short-term randomized clinical trials that reported CRP concentrations before and after fenofibrate treatment. Of the 81 studies examined, 14 studies with 540 patients were found eligible. Data for the change in CRP and corresponding measures of dispersion were extracted for use in the meta-analysis.

Results

The weighted mean CRP concentrations before and after fenofibrate therapy were 2.15 mg/L and 1.53 mg/L (-28.8% change), respectively. Inverse-variance weighted random effects meta-analysis revealed that short-term fenofibrate treatment significantly lowers CRP by 0.58 mg/L (95% CI: 0.36-0.80). There was significant heterogeneity between studies (Q statistic = 64.5, P< 0.0001, I2 = 79.8%). There was no evidence of publication bias and sensitivity analysis revealed that omitting any of the 14 studies did not lead to a different conclusion from the overall meta-analysis result.

Conclusion

Short-term treatment with fenofibrate significantly lowers CRP concentration. Randomized trials that will recruit patients based with high baseline CRP concentrations and with change in CRP as a primary outcome are needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

1. Introduction

C-reactive protein (CRP), a nonspecific marker of inflammation, is a predictor of incident cardiovascular events and mortality [1–5]. Although the exact mechanism through which CRP leads to increased risk for adverse cardiovascular events is unknown, many studies indicate that reducing serum CRP concentration leads to significant benefits with regard to the future cardiovascular events [6, 7]. Whether the reduction in events is directly due to the reduction in CRP or due to the concomitant improvement in lipid profiles remains to be elucidated.

In addition to genetic determinants [4, 8], other factors such as age, race, gender, BMI, smoking, alcohol use, diet and exposure to pollutants are known to affect CRP concentrations in serum [4, 9]. Other than genetic factors, age, race and gender, all the other risk factors for elevated serum CRP are potentially modifiable and they provide an opportunity for intervention. Indeed, studies have shown that exercise, dietary modifications as well as other lifestyle changes lead to a reduction in serum CRP levels [10, 11]. Despite this apparent benefit, exercise, dietary and lifestyle changes have only proven to be effective on a short-term basis because of poor compliance as people tend to revert to their old habits [10]. Lifestyle changes require highly motivated individuals in order to attain long-term benefits, an attribute that limits their application in management of chronic inflammation.

Pharmacologic interventions may provide an effective strategy to manage elevated CRP concentrations, especially among individuals who are not willing or are unable to adhere to dietary and other lifestyle changes [4]. Statins such rosuvastatin or simvastatin are effective in lowering serum CRP concentrations [4, 9, 12–14]. Other studies have shown that niacin, fish oil esters and fenofibrate individually or in combination have an effect on serum CRP concentrations [15]. However, the results from fenofibrate trials have been inconsistent, with some studies indicating a reduction [13, 15] while others indicating no change or an increase in CRP [16–18]. A number of factors may explain this apparent inconsistency in outcome. First, most of the studies may have been underpowered (typically < 50 patients per study). Second, the dose and formulation of fenofibrate varied greatly. Although the different formulations could have been metabolically equivalent regardless of the dose, the associations between fenofibrate and CRP could be further complicated by the variable length of follow-up that ranges from about three weeks to years in studies such as the Fenofibrate Intervention and Event Lowering in Diabetes (FIELD) study [16]. Studies with longer durations could have been influenced by extraneous unmeasured effects such as changes in body weight and other lifestyle attributes. Lastly, fenofibrate studies have used diverse participant pools with varied baseline serum CRP concentrations. Muhlestein et al. [13] have shown that individuals with high baseline CRP concentrations tend to experience a greater reduction in CRP than those with relatively low baseline values. Thus, it is possible that the benefit of fenofibrate is greater in people with elevated serum CRP concentrations in comparison to people with low serum CRP concentrations.

The aim of this study is to determine, through a meta-analysis, the effect of fenofibrate on serum CRP and to estimate the size of this effect in short-term trials (12 weeks or less) since they are unlikely to be confounded by long-term changes in body weight and behaviors such as diet and physical activity.

2. Methods

2.1 Literature searches

We conducted a comprehensive review of studies on the relation between fenofibrate and CRP that were published between 1966 and March 31, 2011. Using PubMed as the primary database, we searched for the following terms: "fenofibrate" and ("CRP" or "hsCRP" or "C-Reactive Protein" or "high-sensitivity C-Reactive Protein"). Search of additional databases including Google Scholar yielded studies that were already in PubMed. All full text articles that met the criteria below were independently retrieved and reviewed for study design and availability of relevant statistics by two reviewers (JY and JK). When duplicate studies were found, only the most complete article was included.

2.2 Selection criteria

Randomized clinical trials that met the following inclusion criteria were selected for the meta-analysis:

-

Fenofibrate was one of the randomized treatment arms.

-

Fenofibrate treatment lasted 3-12 weeks (short-term trial). Since most studies did not have a placebo and CRP can be affected by variables such as change in body weight, we restricted the analyses to short-term randomized studies.

-

Findings were reported in the English language.

-

Relevant statistics for imputing or computing the mean change and corresponding standard error were reported.

Any disagreements on the inclusion of identified studies by the two reviewers (JY and JK) were resolved by discussion or consensus involving a third reviewer (EK). The kappa statistic for the agreement between the first two reviewers was computed.

2.3 Data extraction

Two reviewers (JY and JK) independently extracted data from agreed upon studies using a standard data collection form. Characteristics of each study were recorded. These included the first author, country, publication year, dose and duration of fenofibrate treatment, sample size of fenofibrate treatment arm, patient population, comparison group, mean and standard error of the change in CRP concentration before and after fenofibrate treatment. Data sets extracted by the two reviewers were compared.

For some studies that reported median CRP concentrations before and after fenofibrate treatment, we imputed the mean change in CRP concentrations as the difference between median CRP concentrations before and after fenofibrate treatment. For some studies that did not report the standard error of the change in CRP concentration, we used the formulas below from the Cochrane's handbook for meta-analysis by Higgins et al.[19] to compute or impute the standard error:

-

If the standard deviation (SD) was reported, we computed the standard error (SE) using

-

If the p-value was reported, we computed the t-statistic as t = Tinv (p-value, N-1), where Tinv(p-value, N-1) is a function that returns value t such that P(|X∥ > t) = p-value and X is a random variable that follows a t-distribution with N-1 degrees of freedom. The standard error was then obtained by dividing the mean change (MC) by the t value (SE = MC/t)

-

If neither the SD of the mean change nor the p-value was reported but the standard errors of CRP concentration before and after treatment were reported, we imputed the SE of the change using a correlation coefficient from other studies using the formula below [19]:

Using the sample size from each study as the weight, we computed a pooled correlation coefficient which is the weighted sum of correlation coefficients from all studies with enough information reported and then imputed the standard deviation of mean change as follows:

2.4 Meta-analysis

MIX software version 1.7 [20, 21] was used for all analyses including generation of the Forest plot, Funnel plot and sensitivity analysis plot. To account for both within-study and between-study variation in the meta-analysis we used a random effects model with the inverse of the variance as the weight for each study. We tested for heterogeneity in the studies using Cochran's Q statistic and calculated I2, the percentage of the total variability in effect estimates among trials that is due to heterogeneity rather than chance. The summary effect of each study and the pooled effect from all studies are reported as point estimates and corresponding 95% confidence intervals on a Forest plot. To assess the potential for publication bias we used a Funnel plot. To evaluate whether an individual study had undue influence on the overall meta-analysis result, we performed sensitivity analyses by omitting one of the studies at a time and determining whether statistical conclusion remained the same. Studies were excluded one by one in the order in which they appear in the Forest plot. The study by Kim et al was excluded first and the study by Hogue et al was excluded last. To compute the number of null studies needed to invalidate the observed association from the meta-analysis (i.e., fail-safe N), we used formula number 3 from Orwin [22]. We computed fail-safe Ns for the small and medium Cohen's criterion values (d c ) of 0.2 and 0.5, respectively.

3. Results

3.1. Literature searches

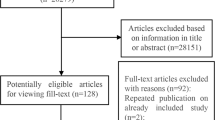

We identified a total of 81 citations in PubMed. As shown in Figure 1, 77 of the studies were published in English, from which we excluded 9 that were not done in humans, 21 that were review articles or not clinical trials and 6 whose full texts we could not obtain. Finally, 41 articles were fully reviewed for study design and relevant statistics. Based on our criteria for study selection, 5 of these were not randomized clinical trials, 4 were long-term studies (> 12 weeks of fenofibrate treatment), 2 had populations that were not of interest given potential confounding by medications (e.g., steroids in rheumatoid arthritis), 4 did not report sufficient statistics for our meta-analysis, one study was too short (lasted < 2 weeks), one reported statistics that seemed implausible and 3 were duplicates. After all the exclusions, 14 studies with a total of 540 patients met our criteria for inclusion in the meta-analysis as summarized in Figure 1 and Tables 1 and 2.

3.2. Efficacy

The weighted mean CRP concentrations before and after fenofibrate therapy were 2.15 mg/L and 1.53 mg/L (-28.8% change), respectively. As shown in Figure 2, short-term treatment with fenofibrate significantly lowers CRP by 0.58 mg/L (95% CI: 0.36-0.84 mg/L). There was significant heterogeneity (Q statistic = 64.5, P < 0.0001) in the studies. The high estimated I2 value (79.8%) confirmed the need to use a random-effects meta-analysis model as we did in this study.

Studies included in the current analyses were conducted in various parts of the world and included participants that varied in their baseline CRP concentrations. We thus reanalyzed the data after stratifying studies by region or baseline CRP concentrations. Seven of the studies were from Europe, 4 from North America and 3 from Asia. The resultant pooled estimates (95% CI) for CRP reduction were -0.72 (-1.01, -0.42; P < 0.0001) for Europe, -0.61 (-1.14, -0.08; P = 0.02) for North America and -0.30 (-0.46, -0.14; P = 0.0002) for Asia. In agreement with previous studies [13], we considered a baseline CRP ≥ 2.0 mg/L to be high. We then carried out an analysis restricted to the studies that had participants with median/mean baseline CRP ≥ 2.0 mg/L [13]. As expected, we observed a larger decrease in CRP following treatment in individuals with high baseline CRP. The pooled estimate from 8 studies with high CRP was -0.72 (95% CI: -1.12, -0.32) mg/L compared to 0.58 (95% CI: 0.36-0.80) mg/L in analyses that pooled all the 14 studies.

3.3. Publication Bias

The Funnel plot (Figure 3) is fairly symmetric, suggesting no evidence for publication bias.

3.4. Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis (Figure 4) suggests that by excluding any of the 14 studies from the meta-analysis the estimated effect will still be within the 95% CI of the estimated effect under the null hypothesis and will not get a different conclusion from the overall meta-analysis result.

Effect of excluding one study at time on the overall estimated effect of fenofibrate on C-reactive protein concentrations. The solid line indicates the pooled estimate while the dashed lines indicate the 95% confidence intervals. The studies were excluded from the analysis in the order they appear in the Forest plot (Figure 2) i.e., the study by Kim et al was excluded first and the study by Hogue et al was excluded last.

3.5. Kappa and fail-safe N

The Kappa for agreement in selecting studies for inclusion in the meta-analysis was 0.47. The fail-safe Ns for the small and medium Cohen's criterion values were 64 and 17 studies, respectively.

4. Discussion

The results from the current meta-analysis show that short-term treatment with fenofibrate leads to a significant reduction in serum CRP concentrations (0.58 mg/L or 28.8% reduction, P < 0.0001) and that the magnitude of the reduction is significantly heterogeneous across studies (Q = 64.5; P < 0.0001). Using the random effects model, the pooled mean absolute reduction of serum CRP was 0.58 mg/L (95% CI: 0.36-0.80) with a Z-score for the overall effect of 12.3 (P < 0.0001). The mean reduction in CRP varied by region and was greatest for studies that had higher baseline CRP concentrations. Sensitivity analyses show that the overall effect is robust since none of the studies has an undue effect on our study findings and stratification by region did not change the conclusion from this study. Our findings do not seem to be affected by publication bias as shown by the Funnel plot.

To date, there is no published meta-analysis on the relation between fenofibrate and CRP. In agreement with our meta-analytic findings, many short-term studies have reported a significant reduction in serum CRP following fenofibrate therapy [23–26]. In support of our finding that fenofibrate reduces CRP concentrations in serum, there are mechanistic human studies showing that fenofibrate therapy reduces the production of inflammatory cytokines by monocytes [14]. Other short-term studies have reported a non-significant reduction in serum CRP concentration following administration of fenofibrate [27]. Some long-term studies have also reported significant reductions in serum CRP following fenofibrate therapy [28] while others reported a non-significant reduction in serum CRP concentrations [29]. However, not all studies investigating the relationship between fenofibrate and serum CRP have reported findings that agree with our findings. Some short-term [17] and long-term [16] studies such the FIELD study have reported an increase in serum CRP following fenofibrate therapy.

The reasons for the disparity in the response to fenofibrate, especially in short-term studies where correlates of CRP such as BMI remain stable, remain obscure. One possible reason for this apparent variability in study findings is that many of the studies have had the disadvantage of having small sample sizes (usually < 50 patients) thus making their estimates of effect likely to be unstable, especially if the baseline CRP concentrations are very low. This disadvantage of small sample sizes could have been overcome by the fairly large sample size of 540 patients in 14 studies used in the current meta-analysis. Moreover, the estimated effect of fenofibrate on CRP is a weighted average, which gives a more precise estimate than any of the individual studies upon which the meta-analysis is based. Also, participants in studies on fenofibrate and CRP were recruited based on their triglyceride concentrations. Although most patients with high triglycerides tend to have high CRP, this is not always the case and may confound results given that lipid-lowering drugs tend to lower CRP more among individuals who have baseline CRP concentrations above 2 mg/L [13] and may increase CRP in patients with very low baseline concentrations. Indeed our analyses restricted to studies with CRP concentrations ≥ 2 mg/L showed that the reduction in CRP in this subset (-0.72; 95% CI: -1.12, -0.32 mg/L) was greater than that observed when all studies are combined (0.58; 95% CI: 0.36-0.80 mg/L). We also observed regional differences in CRP reduction. The reduction in CRP observed for studies conducted in Europe was similar to that observed for studies in North America but much greater than that observed for studies conducted in Asia. The reason is not clear but may in part reflect the differences in baseline CRP and small number of studies conducted in Asia (n = 3) compared to those conducted in Europe (n = 7) or North America (n = 4). However, despite variability by region, all the three pooled estimates indicate a significant reduction in CRP following treatment with fenofibrate. Evaluation of the efficacy of fenofibrate on serum CRP will require randomized studies that recruit patients with high baseline CRP concentrations e.g., ≥ 2 mg/L.

The other potential reason for the variability in findings across studies could be the variation in the strength of fenofibrate used. The dosage of fenofibrate used in most short-term studies we reviewed varied from 145 mg/day [30, 31] to 267 mg/day [32, 33]. Furthermore, various formulations (e.g., micronized vs. non-micronized) were used. Although, different formulations are expected to be metabolically equivalent, this may not always be the case given potential variability in adherence and genetic effects on response to fenofibrate. Since fenofibrate acts mainly through binding onto peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha [34], it is possible that formulations that result in lower amounts of the available active form of fenofibrate will lead to different physiological outcomes and this could explain the observed inconsistencies across studies. In addition to the differences in dosage and/or formulations, most fenofibrate studies on CRP either did not include a placebo arm or used another lipid-lowering drug as the comparison group. Since randomized placebo-controlled studies on fenofibrate are very few, it is difficult to disentangle the true effects of fenofibrate from those that are simply due to regression to the mean, especially given the small size of most short-term fenofibrate trials.

Another potential reason for the variability in the outcome could be the study duration. There is evidence that the effect of fenofibrate on clinical parameters may not be complete within 3 weeks of treatment with fenofibrate (Kabagambe et al., unpublished findings) and this period could be longer as shown in other studies [14]. Other unmeasured variables that influence serum CRP concentrations could change during long-term follow-up but most studies did not have a placebo arm to investigate this effect. However, this was not the case in the Helsinki arm of the Fenofibrate Intervention and Event Lowering Diabetes (FIELD) trial which included a placebo and where individuals were randomized [16]. In this study that included 170 patients with relatively low CRP concentrations (median ≤ 1.8 mg/L), fenofibrate therapy was associated with a 20.1% non-significant increase in CRP (95% CI: -0.8 to 28.8%) over a 5-year follow-up period [16]. Since most studies did not have a placebo group we restricted our analyses to short-term studies (≤ 12 weeks) to minimize potential changes in CRP that are due to changes in patient characteristics e.g., BMI.

Our findings present significant clinical implications in the management of elevated serum concentrations of CRP. To date, only one clinical trial (JUPITER) where patients were recruited based on having high CRP concentrations (≥ 2 mg/L) has been reported [35]. This study [35] showed that compared to the placebo, rosuvastatin lowered CRP by 37%, a magnitude higher than that observed in the current meta-analysis (28.8% mean reduction) of studies with a wide range of baseline CRP concentrations. Whether the effect of fenofibrate among patients with high CRP is comparable to that of resuvastatin is yet to be established. Studies comparing other statins to fenofibrate, showed that among patients with CRP > 2 mg/L, the reduction in CRP due to fenofibrate (-19.0%) was comparable to that due to simvastatin (-24.8%) therapy [13]. In another study [14] the reduction in CRP due to fenofibrate therapy (23 ± 4%) was comparable to that by simvastatin (20 ± 3%), but the patient populations in the two groups were somewhat different with regard to their lipid profiles at study entry. Most studies comparing fenofibrate to other lipid-lowering medications were quite small in sample size (< 50 patients). Until equivalence studies with rosuvastatin as a reference are done, it is plausible to have rosuvastatin as the established approach for managing elevated CRP concentrations. However, some patients experience adverse reactions following administration of statins [36]. Fish oil or fish oil esters are the other option but have side effects too such as undesirable fish odor or increased risk for bleeding and in some studies, including randomized trials, reduction in CRP was not attained [37]. Niacin is the other option and in one study [15] the magnitude of reduction in CRP was higher than that of fenofibrate but as for some statins [38], use of niacin has been associated with glucose dysregulation [15].

Our results confirm that fenofibrate is another feasible alternative therapy in the short-term management of CRP especially among patients who do not tolerate statins, fish oil products, niacin or are unable to adhere to increased physical activity or healthy lifestyle changes. Whether reduction of CRP will be observed among patients with high baseline CRP and followed over a long period as in the ACCORD (Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes) study [39] is yet to be determined.

We acknowledge a number of limitations in our study. First, we used secondary data and thus are unable to rule out potential errors in the original studies. Such errors, if existent, they could bias our conclusions but the sensitivity analyses showed that the conclusion from this meta-analysis is not sensitive to elimination of an individual study. Secondly, although we have attempted to explore publication bias as a potential explanation of the findings, we did not find evidence for it. We believe that publication bias is unlikely to have affected our findings because standard inclusion and exclusion criteria were used in all the studies thus making preferential exclusion/inclusion highly unlikely. Moreover, the computed fail-safe N suggests that we would need 17-64 null studies to make the current meta-analysis show a null association between fenofibrate and CRP.

5.0 Conclusion

We conclude that short-term treatment with fenofibrate is an effective strategy in the management of elevated CRP concentrations. Despite having significant heterogeneity in the studies analyzed, this meta-analysis has shown a significant pooled mean reduction in serum CRP of 0.58 mg/L (95% CI: 0.36-0.80; P < 0.0001). Our findings have significant clinical implications in that fenofibrate is an option for patients who cannot tolerate statins, niacin or fish oil products and their derivatives. Although, fenofibrate has not shown benefit on all-cause mortality, it may be desirable to conduct a trial among people with elevated CRP but who do not tolerate therapies such as statins.

Abbreviations

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SE:

-

Standard error.

References

Kabagambe EK, Judd SE, Howard VJ, Zakai NA, Jenny NS, Hsieh M, Warnock DG, Cushman M: Inflammation biomarkers and risk of all-cause mortality in the reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke cohort. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2011, 174: 284-292. 10.1093/aje/kwr085.

Koenig W, Sund M, Frohlich M, Fischer HG, Lowel H, Doring A, Hutchinson WL, Pepys MB: C-Reactive protein, a sensitive marker of inflammation, predicts future risk of coronary heart disease in initially healthy middle-aged men: results from the MONICA (Monitoring Trends and Determinants in Cardiovascular Disease) Augsburg Cohort Study, 1984 to 1992. Circulation. 1999, 99: 237-242.

Marsik C, Kazemi-Shirazi L, Schickbauer T, Winkler S, Joukhadar C, Wagner OF, Endler G: C-reactive protein and all-cause mortality in a large hospital-based cohort. Clin Chem. United States. 2008, 54: 343-349.

Kones R: Rosuvastatin, inflammation, C-reactive protein, JUPITER, and primary prevention of cardiovascular disease--a perspective. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2010, 4: 383-413.

Jenny NS, Yanez ND, Psaty BM, Kuller LH, Hirsch CH, Tracy RP: Inflammation biomarkers and near-term death in older men. Am J Epidemiol. 2007, 165: 684-695. 10.1093/aje/kwk057.

Kincl V, Panovsky R, Meluzin J, Semenka J, Groch L, Tomcikova D, Jarkovsky J, Dusek L: Association between laboratory markers and presence of coronary artery disease. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2010, 154: 227-233.

Shi B, Ni Z, Cai H, Zhang M, Mou S, Wang Q, Cao L, Yu Z, Yan Y, Qian J: High-sensitivity C-reactive protein: an independent risk factor for left ventricular hypertrophy in patients with lupus nephritis. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2010, 2010: 373-426.

Brull DJ, Serrano N, Zito F, Jones L, Montgomery HE, Rumley A, Sharma P, Lowe GD, World MJ, Humphries SE, Hingorani AD: Human CRP gene polymorphism influences CRP levels: implications for the prediction and pathogenesis of coronary heart disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. United States. 2003, 23: 2063-2069.

Ruckerl R, Greven S, Ljungman P, Aalto P, Antoniades C, Bellander T, Berglind N, Chrysohoou C, Forastiere F, Jacquemin B, et al: Air pollution and inflammation (interleukin-6, C-reactive protein, fibrinogen) in myocardial infarction survivors. Environ Health Perspect. 2007, 115: 1072-1080. 10.1289/ehp.10021.

Dutheil F, Lesourd B, Courteix D, Chapier R, Dore E, Lac G: Blood lipids and adipokines concentrations during a 6-month nutritional and physical activity intervention for metabolic syndrome treatment. Lipids Health Dis. England. 2010, 9: 148-10.1186/1476-511X-9-148.

Hermsdorff HH, Zulet MA, Puchau B, Martinez JA: Fruit and vegetable consumption and proinflammatory gene expression from peripheral blood mononuclear cells in young adults: a translational study. Nutr Metab (Lond). England. 2010, 7: 42-10.1186/1743-7075-7-42.

Ridker PM, Rifai N, Lowenthal SP: Rapid reduction in C-reactive protein with cerivastatin among 785 patients with primary hypercholesterolemia. Circulation. 2001, 103: 1191-1193.

Muhlestein JB, May HT, Jensen JR, Horne BD, Lanman RB, Lavasani F, Wolfert RL, Pearson RR, Yannicelli HD, Anderson JL: The reduction of inflammatory biomarkers by statin, fibrate, and combination therapy among diabetic patients with mixed dyslipidemia: the DIACOR (Diabetes and Combined Lipid Therapy Regimen) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006, 48: 396-401. 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.05.009.

Okopien B, Krysiak R, Kowalski J, Madej A, Belowski D, Zielinski M, Herman ZS: Monocyte release of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-1beta in primary type IIa and IIb dyslipidemic patients treated with statins or fibrates. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. United States. 2005, 46: 377-386.

Wi J, Kim JY, Park S, Kang SM, Jang Y, Chung N, Shim WH, Cho SY, Lee SH: Optimal pharmacologic approach to patients with hypertriglyceridemia and low high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol: randomized comparison of fenofibrate 160 mg and niacin 1500 mg. Atherosclerosis. 2010, 213: 235-240. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.08.068.

Hiukka A, Westerbacka J, Leinonen ES, Watanabe H, Wiklund O, Hulten LM, Salonen JT, Tuomainen TP, Yki-Jarvinen H, Keech AC, Taskinen MR: Long-term effects of fenofibrate on carotid intima-media thickness and augmentation index in subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008, 52: 2190-2197. 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.09.049.

Fegan PG, Shore AC, Mawson D, Tooke JE, MacLeod KM: Microvascular endothelial function in subjects with Type 2 diabetes and the effect of lipid-lowering therapy. Diabet Med. England. 2005, 22: 1670-1676. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01719.x.

Hogue JC, Lamarche B, Tremblay AJ, Bergeron J, Gagne C, Couture P: Differential effect of atorvastatin and fenofibrate on plasma oxidized low-density lipoprotein, inflammation markers, and cell adhesion molecules in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Metabolism. United States. 2008, 57: 380-386.

Higgins JPT, Green S: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration. 2011, [http://www.cochrane-handbook.org]

Bax L, Yu L-M, Ikeda N, Tsuruta H, Moons K: Development and validation of MIX: comprehensive free software for meta-analysis of causal research data. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2006, 6: 50-10.1186/1471-2288-6-50.

Bax L: MIX 1.7: Comprehensive free soft ware for metaanalysis of causal research data. (Last accessed: August 16, 2011), [http://www.meta-analysis-made-easy.com/]

Orwin RG: A fail-safe N for effect size in meta-analysis. Journal of Educational Statistics. 1983, 8: 157-159.

Ikewaki K, Tohyama J, Nakata Y, Wakikawa T, Kido T, Mochizuki S: Fenofibrate effectively reduces remnants, and small dense LDL, and increases HDL particle number in hypertriglyceridemic men-a nuclear magnetic resonance study. J Atheroscler Thromb. Japan. 2004, 11: 278-285. 10.5551/jat.11.278.

Pruski M, Krysiak R, Okopien B: Pleiotropic action of short-term metformin and fenofibrate treatment, combined with lifestyle intervention, in type 2 diabetic patients with mixed dyslipidemia. Diabetes Care. United States. 2009, 32: 1421-1424.

Koh KK, Han SH, Quon MJ, Yeal Ahn J, Shin EK: Beneficial effects of fenofibrate to improve endothelial dysfunction and raise adiponectin levels in patients with primary hypertriglyceridemia. Diabetes Care. United States. 2005, 28: 1419-1424.

Coban E, Ozdogan M, Yazicioglu G, Sari R: The effect of fenofibrate on the levels of high sensitivity C-reactive protein in dyslipidaemic hypertensive patients. Int J Clin Pract. England. 2005, 59: 415-418. 10.1111/j.1368-5031.2005.00428.x.

Phuntuwate W, Suthisisang C, Koanantakul B, Chaloeiphap P, Mackness B, Mackness M: Effect of fenofibrate therapy on paraoxonase1 status in patients with low HDL-C levels. Atherosclerosis. Ireland. 2008, 196: 122-128.

Zhu S, Su G, Meng QH: Inhibitory effects of micronized fenofibrate on carotid atherosclerosis in patients with essential hypertension. Clin Chem. United States. 2006, 52: 2036-2042.

Goto M: A comparative study of anti-inflammatory and antidyslipidemic effects of fenofibrate and statins on rheumatoid arthritis. Mod Rheumatol. 2010, 20: 238-243. 10.1007/s10165-009-0261-2.

Ansquer JC, Bekaert I, Guy M, Hanefeld M, Simon A: Efficacy and safety of coadministration of fenofibrate and ezetimibe compared with each as monotherapy in patients with type IIb dyslipidemia and features of the metabolic syndrome: a prospective, randomized, double-blind, three-parallel arm, multicenter, comparative study. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. New Zealand. 2009, 9: 91-101.

Derosa G, Maffioli P, Salvadeo SA, Ferrari I, Gravina A, Mereu R, Palumbo I, D'Angelo A, Cicero AF: Fenofibrate, simvastatin and their combination in the management of dyslipidaemia in type 2 diabetic patients. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009, 25: 1973-1983. 10.1185/03007990903073159.

Okopien B, Krysiak R, Herman ZS: Effects of short-term fenofibrate treatment on circulating markers of inflammation and hemostasis in patients with impaired glucose tolerance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. United States. 2006, 91: 1770-1778.

Broncel M, Cieslak D, Koter-Michalak M, Duchnowicz P, Mackiewicz K, Chojnowska-Jezierska J: [The anti-inflammatory and antioxidants effects of micronized fenofibrate in patients with visceral obesity and dyslipidemia]. Pol Merkur Lekarski. 2006, 20: 547-550.

Keech AC, Mitchell P, Summanen PA, O'Day J, Davis TM, Moffitt MS, Taskinen MR, Simes RJ, Tse D, Williamson E, et al: Effect of fenofibrate on the need for laser treatment for diabetic retinopathy (FIELD study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. England. 2007, 370: 1687-1697. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61607-9.

Ridker PM, Danielson E, Fonseca FA, Genest J, Gotto AM, Kastelein JJ, Koenig W, Libby P, Lorenzatti AJ, Macfadyen JG, et al: Reduction in C-reactive protein and LDL cholesterol and cardiovascular event rates after initiation of rosuvastatin: a prospective study of the JUPITER trial. Lancet. 2009, 373: 1175-1182. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60447-5.

Meier N, Nedeltchev K, Brekenfeld C, Galimanis A, Fischer U, Findling O, Remonda L, Schroth G, Mattle HP, Arnold M: Prior statin use, intracranial hemorrhage, and outcome after intra-arterial thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. United States. 2009, 40: 1729-1737.

Balk EM, Lichtenstein AH, Chung M, Kupelnick B, Chew P, Lau J: Effects of omega-3 fatty acids on serum markers of cardiovascular disease risk: a systematic review. Atherosclerosis. 2006, 189: 19-30. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.02.012.

Sattar N, Preiss D, Murray HM, Welsh P, Buckley BM, de Craen AJ, Seshasai SR, McMurray JJ, Freeman DJ, Jukema JW, et al: Statins and risk of incident diabetes: a collaborative meta-analysis of randomised statin trials. Lancet. 2010, 375: 735-742. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61965-6.

Buse JB, Bigger JT, Byington RP, Cooper LS, Cushman WC, Friedewald WT, Genuth S, Gerstein HC, Ginsberg HN, Goff DC, et al: Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) trial: design and methods. Am J Cardiol. 2007, 99: 21i-33i.

Kim CJ: Effects of fenofibrate on C-reactive protein levels in hypertriglyceridemic patients. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. United States. 2006, 47: 758-763.

Undas A, Celinska-Lowenhoff M, Domagala TB, Iwaniec T, Dropinski J, Lowenhoff T, Szczeklik A: Early antithrombotic and anti-inflammatory effects of simvastatin versus fenofibrate in patients with hypercholesterolemia. Thromb Haemost. Germany. 2005, 94: 193-199.

Sebestjen M, Keber I, Zegura B, Simcic S, Bozic M, Fressart MM, Stegnar M: Statin and fibrate treatment of combined hyperlipidemia: the effects on some novel risk factors. Thromb Haemost. Germany. 2004, 92: 1129-1135.

Wang TD, Chen WJ, Lin JW, Cheng CC, Chen MF, Lee YT: Efficacy of fenofibrate and simvastatin on endothelial function and inflammatory markers in patients with combined hyperlipidemia: relations with baseline lipid profiles. Atherosclerosis. Ireland. 2003, 170: 315-323.

Krysiak R, Gdula-Dymek A, Bachowski R, Okopien B: Pleiotropic effects of atorvastatin and fenofibrate in metabolic syndrome and different types of pre-diabetes. Diabetes Care. United States. 2010, 33: 2266-2270.

Rosenson RS: Effect of fenofibrate on adiponectin and inflammatory biomarkers in metabolic syndrome patients. Obesity (Silver Spring). United States. 2009, 17: 504-509.

Belfort R, Berria R, Cornell J, Cusi K: Fenofibrate reduces systemic inflammation markers independent of its effects on lipid and glucose metabolism in patients with the metabolic syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. United States. 2010, 95: 829-836.

Acknowledgements

This study is supported by grant # R21DK084560 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

EK conceived the idea. All authors refined the idea and JY and JK searched and extracted data from PubMED. JY, JK and EK performed the analyses. JY and JK drafted the manuscript. All authors edited various copies of the manuscript and approved the final version.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Ye, J., Kiage, J.N., Arnett, D.K. et al. Short-term effect of fenofibrate on C-reactive protein: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabetol Metab Syndr 3, 24 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1758-5996-3-24

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1758-5996-3-24