Abstract

Background

The effect of physical and chemical permeation enhancers on in vitro transdermal permeation of lidocaine was investigated in the horse.

Therefore, the effect of six vehicles (phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), 50% ethanol, 50% propylene glycol, 50% isopropylalcohol, 50% isopropylalcohol/isopropylmyristate and 50% dimethylsulfoxide) was examined as well as the effect of microneedle pretreatment with different needle lengths on transdermal drug delivery of lidocaine.

The skin was obtained from the thorax of six Warmblood horses and was stored up to two weeks at - 20°C. Franz-type diffusion cells were used to study the transdermal permeation through split skin (600 μm thickness). The amount of lidocaine in the receptor fluid was determined by UV–VIS high-performance liquid chromatography.

Results

All investigated vehicle supplementations diminished the transdermal flux of lidocaine through equine skin in comparison to pure PBS except dimethylsulfoxide, which resulted in comparable permeation rates to PBS. The maximum flux (Jmax) was 1.6-1.8 fold lower for lidocaine applied in 50% ethanol, propylene glycol, isopropylalcohol and isopropylalcohol/isopropylmyristate. A significant higher Jmax of lidocaine was observed when lidocaine was applied in PBS onto microneedle pretreated skin with similar permeation rates in both needle lengths. After 6 hours, 1.7 fold higher recovery rates were observed in the microneedle pretreated skin samples than in the untreated control samples. The lagtimes were reduced to 20–50% in the microneedle pretreated skin samples.

Conclusion

Microneedles represent a promising tool for transdermal lidocaine application in the horse with a rapid systemic bioavailability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Lidocaine (lignocaine) represents an amide local anesthetic drug which is also systemically used as an anti-arrhythmic drug [1]. It has recently also gained interest as systemically used prokinetic drug in the treatment of the postoperative ileus in horses [2–5].

Since the transdermal drug administration provides many advantages over oral treatments or injections, the approach of transdermal drug delivery systems has attracted the attention of many researchers all over the world not only in human medicine but also in veterinary research. A topically applied drug has to overcome the main skin barrier, the stratum corneum, which comprises dead corneocytes embedded in a lipid-rich domain mainly consisting of free fatty acids, cholesterol and ceramides [6]. Studies in humans have demonstrated the effectiveness of topically applied lidocaine for treating chronic, neuropathic, osteoarthritic and muscle related pain [7–12]. However, after placement of a single 5% lidocaine patch on each fore leg of horses, no lidocaine was detected in blood samples up to 12 hours of patch application [13]. Aside from this, after topical application of a single dose of 0.02% lidocaine cream to horses no lidocaine was detected in blood or urine samples, while it could be determined in urine samples of dogs in concentrations up to 48 ng/ml after multiple applications to canine skin [14].

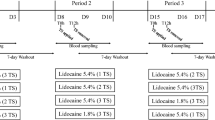

The objective of the current work was, therefore, to assess the impact of chemical and mechanical permeation enhancers on lidocaine permeation through equine skin using a simple diffusion technique. First, five different chemical additives known as permeation enhancers of transdermal drug delivery (diemthylsulfoxide, ethanol, isopropylalcohol, isopropylmyristate and propylene glycol) were investigated for their impact on transdermal lidocaine delivery through equine skin. Second, physical penetration enhancement was performed using microneedles (200 μm and 300 μm long titanium needles) in order to pre-treat the equine skin samples before lidocaine application in the best aqueous solution determined in the first experimental setup.

Method

Chemicals

All chemicals used for the buffer solutions in the present study were of the highest purity available and were purchased from Merck, Darmstadt, Germany. Lidocaine hydrochloride monohydrate and dimethylsulfoxide were purchased from Merck as well. Ethanol was obtained from Applichem GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany. Propylene glycol was purchased from Riedel-de Haen, Seelze, Germany, isopropylalcohol from Lab-Scan, Dublin, Ireland, and isopropylmyristate from Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany.

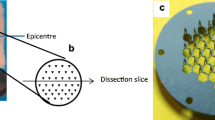

Membranes

The skin was harvested from six male and female (3/3) Warmblood horses after euthanasia in the Clinic for Horses, University of Veterinary Medicine, Foundation, Hannover, for reasons not related to the present study. Thus, an ethical approval was not necessary for our study. The skin over the thoracic region was dissected away and was frozen at -20°C up to two weeks. The average age of the horses was 14 years (±3 years).

In vitropermeation

The skin was defrosted at room temperature and the hair was removed with clippers before an electrical dermatome (Zimmer, Eschbach, Germany) was used to obtain 600 μm thick skin slices. Franz-type diffusion cells (6G-01-00-15-12, PermeGear, Riegelsville, PA, USA, and Gauer Glas, Püttlingen, Germany) with a diffusion area of 1.77 cm2 and a receptor volume of approximately 12 ml were filled with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4; 1 l contains 0.2 g KCl, 8.0 g NaCl, 0.2 g KH2PO4, 1.44 g Na2HPO4 × 2H2O and deionised water) and were maintained at 34°C to provide 32°C skin samples. Small skin pieces (2 × 2 cm) were incubated in PBS for 30 minutes before mounting the skin samples with the stratum corneum side uppermost. After baseline samples (0.4 ml) were taken from the receptor chamber, 1 ml of each test substance solution was applied onto the skin. The permeation of lidocaine out of each test solution was examined in duplicate per animal, while six horses were investigated in total. Samples from the receptor chamber were taken at predefined times up to 6 hours or 22 hours.

Experimental setup

To investigate the effect of different vehicles on lidocaine permeation, the following vehicles were used (2 mg/ml lidocaine): PBS, ethanol (50% in PBS w/w; EtOH), propylene glycol (50% in PBS w/w; PG), isopropylalcohol (50% in PBS w/w; IPA), isopropylalcohol/isopropylmyristate (50% in PBS w/w; IPM/IPA), and dimethylsulfoxide (50% in PBS w/w; DMSO). Furthermore, the effect of microneedle pretreatment on transdermal drug delivery of lidocaine was investigated using two microneedle rollers (Medik8, London, United Kingdom) with different needle lengths (200 μm and 300 μm), both of which possessed of 192 titanium needles in a cylindrical arrangement (diameter of 150 μm at the basis). The microneedle pretreatment was performed after an incubation phase in PBS for 30 minutes using skin samples which were placed on a styropor panel and fixed with needles beyond the subsequent diffusion area of the skin samples. The microneedle rollers were rolled in four axes radial [15] over the skin surface before 1 ml of the lidocaine solution in PBS was applied. Sample withdrawal from the receptor chamber (0.4 ml) was performed at predefined times with replacement by 0.4 ml PBS. The donor chambers were covered with parafilm (BRAND GmbH & CO KG, Wertheim, Germany).

Analysis

The receptor medium samples were analysed by high-performance liquid chromatography utilizing a model 126 pump at 1 ml/min, a model 168 UV–VIS detector at 240 nm, and a model 507 autosampler (all Beckman, Fullerton, CA, USA) for the injection of 100 μl. A reversed phase HPLC column (LiChroCART 250–4, LiChrospher® 100 RP-18, 5 μm, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) combined with a guard column (LiChroCART® 4–4 mm, LiChrospher®100 RP-18 (5 μm), Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) were used at 40°C. The mobile phase comprises 78% phosphate buffer (pH 5.5) and 20% acetonitrile, 1% triethylamine and 1% acetic acid degassed via sonication.

Data analysis

An automated algorithm [16] was used to calculate the maximum flux (Jmax, μg/cm2/h) and the apparent permeability coefficient (Papp, cm/h). Values from replicated in vitro experiments (2 replicates per treatment) at the same individual were used as average. Differences between diffusion parameters of control (PBS) and of the chemical additives/microneedle pretreated skin samples were evaluated using Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunnett´s multiple comparison test (GraphPad Prism 4.01 Software Inc., San Diego, USA). A 0.05 significance level was adopted.

Results

Lidocaine was able to permeate through equine skin out of all investigated formulations (Figure 1). The highest permeation of lidocaine was observed after administration of lidocaine in pure PBS and 50% DMSO. Formulations with 50% EtOH, PG, IPA and IPM/IPA diminished the permeation rate of lidocaine.

Parameters describing the features of the different vehicles on in vitro permeation of lidocaine are summarized in Table 1. Lidocaine in PBS showed the highest maximum flux Jmax and the shortest lagtime through equine skin compared to EtOH, PG, IPA and IPM/IPA. Statistical significant differences were found for Jmax and the apparent permeability coefficients of control vs. EtOH and PG (p < 0.05). The 6 hour-recoveries of lidocaine in 50% EtOH, PG and IPA (p < 0.01) and IPM/IPA (p < 0.05) were significantly different from the 6 hour-recovery of lidocaine in PBS (1.6 to 2.2-fold lower). The addition of 50% DMSO resulted in a comparable lidocaine permeation data to lidocaine applied in pure PBS. Although the lagtimes ranged from the mean of 0.9 hours (PBS) to 2.2 hours (IPA), no statistical significant differences were determined. There was no statistical significance between the different chemical additives.

The microneedle pretreatment with both needle lengths significantly enhanced the permeation of lidocaine (Figure 2). Both needle lengths resulted in 1.4 higher permeation rates of lidocaine compared to control (p < 0.01) with diminished lagtimes. The lagtime was reduced from 1 hour in the untreated control skin to 0.8 hours in the 200 μm long microneedle treated skin samples and to 0.5 hours in the 300 μm long microneedle treated skin samples (Table 2). The 6-hour recoveries were approximately 1.7 fold higher in the microneedle pretreated skin samples (p < 0.05 (200 μm) and p < 0.01 (300 μm)).

Discussion

Although there are many reports demonstrating that alcohols may act as skin permeability enhancers as solubilizing agents with delipidisation potential [17–20], in the present study no enhancing effect was observed for EtOH or IPA supplementation on transdermal permeation of lidocaine. Permeation of lidocaine, on the contrary, was diminished to alcohol supplementation to the vehicle compared to pure PBS which served as control. There are also various reports about permeation enhancements of sulfoxides like DMSO [19, 21, 22], which can increase lipid fluidity and promote drug partition [23, 24] or polyols like PG [17, 25, 26], which are described to solvate α-keratin and occupy hydrogen bonding sites [27, 28]. IPM exhibits a direct action on the stratum corneum, permeates into liposome bilayers and increases fluidity of membranes [19, 29], but even this aliphatic fatty acid esters diminished lidocaine permeation through equine skin (53,54) comparable to PG. Only DMSO supplementation to the vehicle resulted in higher permeation rates of lidocaine compared to PG, IPA, EtOH or IPM/IPA, but similar permeation levels to pure PBS. Thus, the investigated chemicals show no effectiveness as permeation enhancers for lidocaine through equine skin, which may be due to the physicochemical nature of lidocaine. Furthermore, species react different to permeation enhancers and topically applied drugs, which has been shown e.g. for lidocaine patches in various species. 5% lidocaine patches administered to humans, cats and dogs resulted in measureable lidocaine concentrations in plasma of the examined species [30–33], while there was a lack of systemic absorption of lidocaine from 5 % patches placed on horses [13]. Furthermore, DMSO supplementation to the vehicle of transdermal applied lidocaine onto guinea pig skin resulted in higher transdermal permeation rates of lidocaine [34].

Interspecies differences in the success of penetration enhancement via chemical additives may be due to differences in skin morphology and biochemistry. Since the main skin barrier is maintained by the stratum corneum, its histology and lipid composition is of high importance. Concerning various reports about interspecies differences in these parameters [35–37], the lack of chemical penetration enhancement in the present study may be due to differences in the skin lipid composition of horses [38] compared with other species [37, 39, 40].

Due to the lack of chemical additives to enhance percutaneous permeation of lidocaine through equine skin, the second part of the present study was the investigation of the impact of mechanical permeation enhancers (microneedles) on lidocaine permeation through equine skin. Microneedles represent mechanical permeation enhancers in order to overcome the main skin barrier, the stratum corneum. This technology has been established to perforate the skin barrier without inducing pain or bleeding, as the needles are too short to stimulate the nerves and to damage blood vessels in the dermis [41, 42]. Thus, the produced holes act as shunt ways for topically applied drugs with low permeability. In agreement with recent studies, microneedles enhance transdermal drug delivery of topically applied drugs [15, 43–46]. After microneedle pretreatment, 1.7 fold higher amounts of lidocaine were determined in the present study in the receptor fluid after 6 hours with a 1.4 fold higher apparent permeability coefficient in the microneedle pretreated skin samples. Furthermore, the lag-times were reduced by 23% and 50% in dependence on the microneedle lengths. Consequently, from the present results it can be concluded that microneedle pretreatment results in a rapid onset of lidocaine action within the skin and in the organism, which is in accordance with recent studies about lidocaine-containing microneedle products with a rapid, safe, and prolonged local analgesic action [47, 48].

Conclusion

In conclusion, the results of the present study demonstrate significant differences in transdermal permeation of lidocaine dissolved in various vehicles and the high potential of microneedle pretreatment on transdermal permeation enhancement of lidocaine through equine skin.

Clinical relevance

For the therapy of a postoperative ileus a plasma level of lidocaine of 1-2 μg/ml plasma is necessary [49]. Since the mean blood volume of a horse is 50 l [50], 50-100 μg lidocaine have to be in the organism in order to gain effective plasma levels. With the assumption of 7.5% recovery in the blood (recovery of 300 μm long microneedles in the acceptor chamber after 6 hours) a transdermal formulation containing 0.6-1.3 mg/ml may be adequate to reach effective plasma levels (when applied on microneedle perforated skin of the thorax). But therefore, several in-vivo studies in horses have to be performed.

Abbreviations

- (DMSO):

-

Dimethylsulfoxide

- (EtOH):

-

Ethanol

- (IPA):

-

Isopropylalcohol

- (IPM):

-

Isopropylmyristate

- (Jmax):

-

Maximum flux

- (PBS):

-

Phosphate-buffered saline

- (PG):

-

Propylene glycol.

References

Doherty TJ, Seddighi MR: Local anesthetics as pain therapy in horses. Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract. 2010, 26: 533-549.

Cook VL, Blikslager AT: Use of systemically administered lidocaine in horses with gastrointestinal tract disease. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2008, 232: 1144-1148.

Rusiecki KE, Nieto JE, Puchalski SM, Snyder JR: Evaluation of continuous infusion of lidocaine on gastrointestinal tract function in normal horses. Vet Surg. 2008, 37: 564-570.

Torfs S, Delesalle C, Dewulf J, Devisscher L, Deprez P: Risk factors for equine postoperative ileus and effectiveness of prophylactic lidocaine. J Vet Intern Med. 2009, 23: 606-611.

Guschlbauer M, Hoppe S, Geburek F, Feige K, Huber K: In vitro effects of lidocaine on the contractility of equine jejunal smooth muscle challenged by ischaemia-reperfusion injury. Equine Vet J. 2010, 42: 53-58.

Lampe MA, Burlingame AL, Whitney J, Williams ML, Brown BE, Roitman E, Elias PM: Human stratum corneum lipids: characterization and regional variations 3. JLipid Res. 1983, 24: 120-130.

Galer BS, Sheldon E, Patel N, Codding C, Burch F, Gammaitoni AR: Topical lidocaine patch 5% may target a novel underlying pain mechanism in osteoarthritis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2004, 20: 1455-1458.

Burch F, Codding C, Patel N, Sheldon E: Lidocaine patch 5% improves pain, stiffness, and physical function in osteoarthritis pain patients. A prospective, multicenter, open-label effectiveness trial. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2004, 12: 253-255.

Meier T, Faust M, Huppe M: Schmucker P: [Reduction of chronic pain for non-postherpetic peripheral neuropathies after topical treatment with a lidocaine patch]. Schmerz. 2004, 18: 172-178.

Meier T, Wasner G, Faust M, Kuntzer T, Ochsner F, Hueppe M, Bogousslavsky J, Baron R: Efficacy of lidocaine patch 5% in the treatment of focal peripheral neuropathic pain syndromes: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Pain. 2003, 106: 151-158.

Kivitz A, Fairfax M, Sheldon EA, Xiang Q, Jones BA, Gammaitoni AR, Gould EM: Comparison of the effectiveness and tolerability of lidocaine patch 5% versus celecoxib for osteoarthritis-related knee pain: post hoc analysis of a 12 week, prospective, randomized, active-controlled, open-label, parallel-group trial in adults. Clin Ther. 2008, 30: 2366-2377.

White WT, Patel N, Drass M, Nalamachu S: Lidocaine patch 5% with systemic analgesics such as gabapentin: a rational polypharmacy approach for the treatment of chronic pain. Pain Med. 2003, 4: 321-330.

Bidwell LA, Wilson DV, Caron JP: Lack of systemic absorption of lidocaine from 5% patches placed on horses. Vet Anaesth Analg. 2007, 34: 443-446.

Thomas AD, Bowater IC, Vine JH, McLean JG: Uptake of drugs from topically applied anti-inflammatory preparations applied to racing animals. Aust Vet J. 1997, 75: 897-901.

Stahl J, Wohlert M, Kietzmann M: Microneedle pretreatment enhances the percutaneous permeation of hydrophilic compounds with high melting points. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2012, 13: 5.

Niedorf F, Schmidt E, Kietzmann M: The automated, accurate and reproducible determination of steady-state permeation parameters from percutaneous permeation data. Altern Lab Anim. 2008, 36: 201-213.

Mills PC: Vehicle effects on the in vitro penetration of testosterone through equine skin. Vet Res Commun. 2007, 31: 227-233.

Pabla D, Zia H: A comparative permeation/release study of different testosterone gel formulations. Drug Deliv. 2007, 14: 389-396.

Thong HY, Zhai H, Maibach HI: Percutaneous penetration enhancers: an overview. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2007, 20: 272-282.

Santos P, Watkinson AC, Hadgraft J, Lane ME: Influence of penetration enhancer on drug permeation from volatile formulations. Int J Pharm. 2012, 439: 260-268.

Zafar S, Ali A, Aqil M, Ahad A: Transdermal drug delivery of labetalol hydrochloride: Feasibility and effect of penetration enhancers. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2010, 2: 321-324.

Marren K: Dimethyl sulfoxide: an effective penetration enhancer for topical administration of NSAIDs. Phys Sportsmed. 2011, 39: 75-82.

Scheuplein RJ, Blank IH: Permeability of the skin. Physiol Rev. 1971, 51: 702-747.

Sekura DL, Scala J: The percutaneous absorption of alkyl methyl sulfoxides. Adv Biol Skin. 1972, 12: 257-269.

Gee CM, Watkinson AC, Nicolazzo JA, Finnin BC: The Effect of Formulation Excipients on the Penetration and Lateral Diffusion of Ibuprofen on and within the Stratum Corneum Following Topical Application to Humans. J Pharm Sci. 2014, 103: 909-919.

Kietzmann M, Blume B: Percutaneus absorption of betamethasone from different formulations using the isolated perfused bovine udder. In Vitro Toxikol. 1997, 10: 11-15.

Herai H, Gratieri T, Thomazine JA, Bentley MV, Lopez RF: Doxorubicin skin penetration from monoolein-containing propylene glycol formulations. Int J Pharm. 2007, 329: 88-93.

Mollgaard B, Hoelgaard A: Vehicle effect on topical drug delivery. I. Influence of glycols and drug concentration on skin transport. Acta Pharm Suec. 1983, 20: 433-442.

Zhao N, Cun D, Li W, Ma X, Sun L, Xi H, Li L, Fang L: In vitro percutaneous absorption enhancement of granisetron by chemical penetration enhancers. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2012

Ko J, Weil A, Maxwell L, Kitao T, Haydon T: Plasma concentrations of lidocaine in dogs following lidocaine patch application. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2007, 43: 280-283.

Ko JC, Maxwell LK, Abbo LA, Weil AB: Pharmacokinetics of lidocaine following the application of 5% lidocaine patches to cats. J Vet Pharmacol Ther. 2008, 31: 359-367.

Leopold A, Wilson S, Weaver JS, Moursi AM: Pharmacokinetics of lidocaine delivered from a transmucosal patch in children. Anesth Prog. 2002, 49: 82-87.

Gammaitoni AR, Davis MW: Pharmacokinetics and tolerability of lidocaine patch 5% with extended dosing. Ann Pharmacother. 2002, 36: 236-240.

Mohammadi-Samani S, Jamshidzadeh A, Montaseri H, Rangbar-Zahedani M, Kianrad R: The effects of some permeability enhancers on the percutaneous absorption of lidocaine. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2010, 23: 83-88.

Monteiro-Riviere NA, Bristol DG, Manning TO, Rogers RA, Riviere JE: Interspecies and interregional analysis of the comparative histologic thickness and laser Doppler blood flow measurements at five cutaneous sites in nine species. J Invest Dermatol. 1990, 95: 582-586.

Monteiro-Riviere NA, Hobson DW: Comparative anatomy, physiology and biochemistry of mammalian skin. Dermal and ocular toxicology. 1991, Boca Raton: CRC. Press, 3-71.

Stahl J, Niedorf F, Kietzmann M: Characterisation of epidermal lipid composition and skin morphology of animal skin ex vivo. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2009, 72: 310-316.

Downing DT: Colton SWt: Skin surface lipids of the horse. Lipids. 1980, 15: 323-327.

Lampe MA, Williams ML, Elias PM: Human epidermal lipids: characterization and modulations during differentiation 2. JLipid Res. 1983, 24: 131-140.

Gray GM, Yardley HJ: Lipid compositions of cells isolated from pig, human, and rat epidermis 5. JLipid Res. 1975, 16: 434-440.

Kaushik S, Hord AH, Denson DD, McAllister DV, Smitra S, Allen MG, Prausnitz MR: Lack of pain associated with microfabricated microneedles. Anesth Analg. 2001, 92: 502-504.

Prausnitz MR, Mikszta JA, Cormier M, Andrianov AK: Microneedle-based vaccines. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2009, 333: 369-393.

Wu Y, Qiu Y, Zhang S, Qin G, Gao Y: Microneedle-based drug delivery: studies on delivery parameters and biocompatibility. Biomed Microdevices. 2008, 10: 601-610.

Martanto W, Davis SP, Holiday NR, Wang J, Gill HS, Prausnitz MR: Transdermal delivery of insulin using microneedles in vivo. Pharm Res. 2004, 21: 947-952.

McAllister DV, Wang PM, Davis SP, Park JH, Canatella PJ, Allen MG, Prausnitz MR: Microfabricated needles for transdermal delivery of macromolecules and nanoparticles: fabrication methods and transport studies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003, 100: 13755-13760.

Wu XM, Todo H, Sugibayashi K: Enhancement of skin permeation of high molecular compounds by a combination of microneedle pretreatment and iontophoresis 1. J Control Release. 2006, 118: 189-195.

Kochhar JS, Lim WX, Zou S, Foo WY, Pan J, Kang L: Microneedle integrated transdermal patch for fast onset and sustained delivery of lidocaine. Mol Pharm. 2013, 10: 4272-4280.

Zhang Y, Brown K, Siebenaler K, Determan A, Dohmeier D, Hansen K: Development of lidocaine-coated microneedle product for rapid, safe, and prolonged local analgesic action. Pharm Res. 2012, 29: 170-177.

Van Hoogmoed LM, Nieto JE, Snyder JR, Harmon FA: Survey of prokinetic use in horses with gastrointestinal injury. Vet Surg. 2004, 33: 279-285.

Householder DD, Douglas RH: Total blood volume and thoroughbred racing peformance. J Equine Vet Sci. 2005, 25: 14-15.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the technical help of Mareike Kölln, Robert Kirchner and Theiss Wystemp as well as Caroline Gietz and Amelie Teepe for skin acquisition.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Authors’ contributions

JS planned the study together with MK. JS coordinated the experiments, made the analysis and wrote the manuscript. Both authors have edited the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Stahl, J., Kietzmann, M. The effects of chemical and physical penetration enhancers on the percutaneous permeation of lidocaine through equine skin. BMC Vet Res 10, 138 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-6148-10-138

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-6148-10-138