Abstract

Background

Epstein-Barr virus has been proved to be associated with many of the human malignancy including gastric carcinoma, one of the most important human malignancies in the world. There has been no study about the presence of EBV in gastric adenocarcinoma in Iran.

Methods

We examined the presence of EBV in 273 formalin fixed paraffin-embedded cases of gastric carcinoma from Cancer institute of Tehran University, from 1969 to 2004. In situ hybridization of EBV-encoded small RNA-1 (EBER-1) was conducted. The strain of positive cases was examined by means of polymerase chain reaction and/or restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis.

Results

We found 9 (3%; 95% CI = 1–5%) EBV positive cases. The gender difference was not statisticaly significant. The proportion of EBV-GC cases in diffuse type was higher than intestinal type (OR = 0.08; 95% CI = 0.002–0.64). EBV-GC cases had no relation with age, location and invasion. Six out of 9 EBV-GC cases were born during the period between 1928 and 1930. All 9 cases were Type A. Prototype F was seen in 6 out of 8 cases. Type "i" was found in 8 cases and type I in 1 case. XhoI+ and XhoI- polymorphism accounted 6 and 3 of the cases, respectively.

Conclusion

Our study is the first to describe the frequency of EBV-GC in Iran and the Middle East, highlighting a very low prevalence with specific clinicopathologic features. The predominance of EBV-GC birth year in a fixed period, suggests that EBV infection or other events at early childhood may be related to the development of EBV-GC later in the life. The predominance of the type "i" and XhoI+ cases are contradictory to other studies in Asia and is similar to what is reported from Latin American countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is a ubiquitous double stranded DNA virus from human herpes virus family, which has B-lymphotropism [1]. More than 90% of adults in the world have serologic evidence of infection with this virus [1]. It is acquired during early childhood and the age of infection is much lower in undeveloped countries with low socioeconomic condition [1]. Following primary infection, the virus establishes a life-long latent infection in the B-cell lymphocytes where it is present in 1 in 105–106 circulating cells [2]. It expresses some antigens in this latent phase, which are proved to have some oncogenic properties [3–8]. There are many documents about causal association between EBV and lymphoid malignancies such as Burkitt's lymphoma in equatorial Africa [9], nasal T/NK cell lymphoma [10], Hodgkin's lymphoma [11] and B-cell lymphoma in immunosuppressed patients [12]. EBV has also the capacity of infecting epithelial cells, and also has tumorogenic effect in these cells from which the nasopharyngeal carcinoma is one of the important prototypes [13].

The first report of EBV involvement in gastric carcinoma was published in 1990 in lymphoepithelial carcinoma of the stomach [14]. Consequently, in 1992 Shibata and Weiss reported EBV detection in 16% of ordinary gastric carcinoma in U.S. [15]. Since then, the prevalence of EBV-associated gastric carcinoma (EBV-GC) has been investigated and reported in various countries which ranged between 3 to 18% [15–34] with the lowest prevalence in Papua New Guinea, Pakistan and Korea which is between 1 to 3% and the highest in Germany and U.S. which is 16 to 18%.

There are many evidences of causal relationship between EBV and gastric carcinoma such as: monoclonality of the viruses in neoplastic cells which was demonstrated by unique terminal repeat of EBV DNA [35]; uniform presence of EBV in all tumoral cells detected by in situ hybridization of EBER-1, but not in surrounding epithelial cells [15–34] and elevation of IgG and IgA antibodies against viral capsid antigen several months before clinical presentation of the disease [36].

EBV-GC shows some constant characteristic clinicopathologic features such as predisposition to upper two-third of the stomach [15–17, 19–31]; a moderately differentiated tubular to poorly differentiated solid type of histology [16–22, 32, 33]; having no effect in stromal invasion and survival [15, 16]; and male predominance in most of the studies. However, the last one is not seen in some exceptional studies which are performed in Mexico [32, 37], Chile [16] and China [38]. Age dependence is not evident in most studies. However studies in Colombia [19], and Kazakhstan [28] show a higher prevalence among younger patients.

EBV has two major types, type 1 and type 2 that differ in their capacity to transform B-lymphocytes into a state of continuous proliferation [39]. Type 1 is predominant in Western and Asian countries while B type is predominant in Africa and is seen more commonly in immunosuppressed patients [40, 41]. Besides, there are three other variants, which are distinguished by restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) using BamHI and XhoI restriction endonuclease enzymes. At the BamHI-F region Prototype F has the worldwide distribution and 'f' variant which has an extra site for enzyme is predominant in southern China and is associated with nasopharyngeal carcinoma [42, 43]. Polymorphism in BamHI-W1/I1 boundary region leads to two variants; type I and 'i'. Type I which is predominant in Japan and China has no site for BamHI enzyme [44, 45] and type 'i' with an extra BamHI site is seen more commonly in Western countries [46]. Finally, polymorphism in XhoI restriction site in axon 1 of the LMP1 gene defines XhoI+ which is more prevalent in Western countries [47] and XhoI-, which is frequently seen in Asia [44].

Iran is one of the countries which have a high incidence of gastric carcinoma with an annual incidence of 26.1 per 100,000 for males and 11.1 for females. It is the second most prevalent cancer and the first leading cause of cancer-related deaths in men in Iran [48]. However, there is no study about the prevalence or genotype of EBV in gastric cancer in this area. Therefore, we decided to evaluate it in the oldest referral center for gastric cancer in Iran.

Methods

Specimens

We examined 273 surgically resected gastric cancer cases in this study. The cases were randomly selected from 1325 gastric cancer cases registered in cancer institutes of Tehran University between 1969 – 2004 which have intact paraffin blocks and pathologic reports. Formalin fixed paraffin-embedded tissue from these cases were selected and sent to Kagoshima University Graduate School of Medical and Dental Sciences, Japan, for further molecular evaluations. Pathologic data were obtained with re-evaluation of H&E stained slides by two pathologists (AA & SGS). All available demographic data were obtained from the available pathologic and medical reports of the patients.

Pathology

All the specimens were re-classified in regard of predominant histological pattern as intestinal and diffuse type according to Lauren classification [49] and sub-classified according to the guidelines of the Japanese research society for gastric cancer [50] to well differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma (tub1), moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma (tub2), solid poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma (por1), non-solid poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma (por2), signet ring cell carcinoma (sig), mucinous carcinoma (muc) and poorly differentiated lymphoepithelial-like carcinoma (LE).

The tumors location according to predominant location of the lesions were classified as upper third or cardia, middle third or body and lower third or antrum according to the guidelines of the Japanese research society for gastric cancer [50]. There was no multifocal case in our study.

The depth of invasion was classified as mucosal, sub-mucosal, muscularis propria and serosal involvement.

In situ hybridization

EBV was identified by the expression of EBV-encoded small RNA-1 (EBER-1). In situ hybridization with a complementary digoxigenin-labeled 30-base oligomer was used to detect the EBER-1 according to the procedure previously described by Chang et al [51]. 4–5-μm sections mounted on silane-coated glass slides were prepared for each case. The tissue on the slides was deparaffinized, rehydrated, predigested with pronase, prehybridized, and then hybridized overnight at 37°C with 0.5 ng digoxigenin-labeled probe. The hybridization signal was detected by an antidigoxigenin antibody-alkaline phosphatase conjugate. Sections from a patient with known EBER-positive gastric carcinoma were used for a positive control, and sense probe to EBER-1 was used for a negative control for each procedure.

Preparation of DNA

The formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded specimen was cut into 10 μm thick slices, and DNA sample was prepared following the method described by Greer et al [52]. Briefly, the slices were treated with xylene and ethanol and centrifuged at 22,000 g for 20 min, and the resulting pellet was resuspended in 100 μl of digestion buffer (1 M Tris, pH 8.0, 50 mM EDTA, 0.5% Tween 20) with 200 μg/ml Proteinase K and incubated at 55°C overnight. After 10 min boiling at 100°C, extraction and precipitation of DNA was carried out with phenol-chloroform and ethanol, respectively.

Primers and probes

Four different regions, EBNA-3C, BamHI-F, BamHI-W1/I1, and XhoI site in LMP1, were used to determine viral genotypes. Table 1 shows the list of primer sets and probes used in the present study.

Types 1 and 2 were recognized by amplification of U2 region of EBNA-3C gene by primers described by Sample et al [53] which yielded 153 and 246-bp fragments, respectively. They are recognized by Southern blot hybridization (SBH) with type-specific internal probes described by Sample et al [53]. The BamHI-F region was amplified by the primers set described by Lung et al [54]. The consequent 198-bp fragment was digested by BamHI restriction enzyme which yelled a 198-bp fragment in the case of wild type F and 127-bp and 71-bp fragments in the case of 'f' variant. The wild-type F and the f variants were confirmed by SBH with the internal probe as described before [55]. To distinguish I/i variants, the BamHI-W1/I1 region was amplified using the primer set described by Lung et al [54]. Digestion with BamHI restriction enzyme yelled 205-bp fragment in type I and 130-bp and 75-bp fragments in the case of 'i'. They were also confirmed by SBH with a cloned BamHI-I DNA fragment probe. Analysis of polymorphism in exon 1 of LMP1 gene was performed using a primer set described by Sandvej et al [56] which resulted 113-bp fragments. After digestion with XhoI restriction enzyme, XhoI+ cases which contain XhoI cleavage site (XhoI kept) show 67-bp and 46-bp fragments but XhoI- cases show the original undigested 113-bp PCR product. The 113 bp fragment of PCR product of B95-8 cell line was used as the probe to confirm XhoI cleavage site of LMP1 by SBH [57].

For type 1, wild type F, type I, and XhoI- viruses the B95-8 cell line was used as positive control. The cell lines AG786 and Akata and the cloned BamHI-'f' and BamHI-"i" DNA fragments served as positive controls for type 2, XhoI-, "f" variant, and type "i" viruses, respectively. Human herpes virus 6 infected cell line MOLT-4 used as negative control [58].

Polymerase chain reaction

Amplification of target DNAs was carried out using 2 μl of DNA and mixture of 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 50 mm KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 200 μM dNTPs, 1 μM of each primer and 1.0 U Taq Polymerase (Hot Star, Qiagen, Germany) in a final volume of 25 μl mixture. The protocol used for amplification of EBNA-3C gene was one cycle at 95°C for 15 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 1 min, annealing at 46°C for 1 min and elongation at 72°C for 1 min and finally ended with 5 min at 72°C. The protocol used for BamHI-F, BamHI-W1/I1 and XhoI site amplification was one cycle at 95°C for 5 min followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 1 min, annealing at 43°C for 1 min and elongation at 72°C for 1 min and finally ended with 5 min at 72°C. Electrophoresis in a 2% agarose gel and staining with 0.5 μg/ml of ethidium bromide was carried out to identifying the PCR products.

Restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis

Amplified DNA products (15 μl) were digested with 10 U of BamHI or XhoI restriction enzymes, according to manufacturer's instruction and visualized by electrophoresis in a 2% agarose gel stained with 0.5 μg/ml of ethidium bromide and transferred onto a nylon membrane for SBH.

Southern blot hybridization

Specificity of PCR reaction was confirmed by SBH. The electrophoretic DNA was transferred onto a Hybond N+ nylon membrane (Amersham, Pharmacia Biotech, UK) by capillary blotting using 0.4 N NaOH solution. Membranes were prehybridized with hybridization buffer for 1 h at 42°C. After adding the probe, hybridization was carried out overnight at 42°C. Probes of types A and B, and BamH-I F were labeled with Dig oligonucleotide 3'-end labeling kit and detected by Dig luminescent detection kit (Boehringer Mannheim, Germany). For detecting the BamHI-I fragment and XhoI polymorphism in LMP1, hybridization was carried out using the ECL direct labeling and detection kit (Amersham, Pharmacia Biotech, UK) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was done using LogExact 7.0 software (a statistical package for regression procedure featuring exact method); Cytel Studio 7.0.0 package (Cytel Software Corporation, 2005). Exact test of binary logistic analysis was conducted to compare the proportion of EBV positive cases among gastric adenocarcinoma. Sex, age groups (<50, 50–69 and ≥ 70 years), anatomical location of tumor (antrum, body and cardia), invasion of tumor (serosa, others) and Lauren's histological classification were included as independent variables. Multinominal variables were divided to n-1 dummy binominal variables (n was the number of categories). Odds ratio with 95% confidence interval was calculated for each category. Type 1 error (α) was set at 0.05. All p values were two-sided.

Results

We examined 273 gastric cancers including 196 (72%) males and 77 (28%) females. The mean age was 57.3 ± 11.3 (SD) years (range: 24–90; median: 58). Most of them (108 cases; 66%) were between 50 to 69 years, 54 (20%) cases were under 50 and the remaining were over 70 years. One hundred thirty cases (48%) were located in antrum, and 64 (23%) and 71 (26%) cases were located in body and cardia, respectively. In 5 cases the location was not defined and in 3 cases all the gastric wall were involved (linitis plastica) which were not included in statistical analysis. As shown in table 2, most of the cases were intestinal type (56%).

Prevalence of EBV positive cases

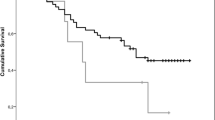

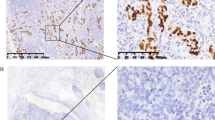

EBER-1 was detected in nine out of 273 cases (3%) which were considered as EBV-GC. The signal was restricted only to the nuclei of tumoral cells but not found in non-tumoral cells (Fig. 1).

Factors associated with EBV positive cases

Table 3 shows the frequencies of EBV-GC by age, gender, location, histology and invasion as well as the result of logistic analysis.

Gender and age

Eight out of 188 (4%) male cases and 1 out of 76 (1%) female cases were EBV positive. Although there was a male predominance in this study, it was not statistically significant (p = 0.5). There was also no relationship between age and EBV-GC (p = 1).

Tumor location

According to anatomic location, 5 out of 64 (8%) body tumors, 1 out of 71 (1%) cardiac tumors and 3 out of 130 (2%) antral tumors were EBV associated. Although most of EBV-GC were located in upper two-thirds, it was not significant statistically (p = 0.1).

Histological type

Based on Lauren's classification, 8 out of 121 (7%) diffuse type cases were EBV associated but only 1 out of 152 intestinal type was EBV positive, which was statistically significant (p = 0.009). According to Japanese classification, por2 and por1 were the predominant histologic types in EBV-GC (Table 2), but regarding the low number of cases in each group statistical analysis could not be performed.

Invasion

In this study there were only 2 cases which were limited to submucosa and none of them shows EBER-1 signal in ISH. Thus, considering of the low number, these cases were not considered in statistical analysis. There was no difference between EBV positive and negative cases regarding invasion to serosa and muscularis propria (p = 0.24).

Other findings

The noteworthy point in our study was the fact that 6 out of 9 EBV-GCs patients were born between "1928–1930". However, the statistical analysis was not made because of the low number.

Genotyping

The subtype of EBV genome was determined in all 9 cases. All of our cases were type 1. The BamHI-F region was amplified successfully in 8 out of 9 of EBV-GCs, which six of them showed prototype F (Fig. 2). Amplification of BamHI-I/WI1 was successful in all of the cases and, except one; all the cases were "i" type (Fig. 3). Analysis of polymorphism in exon 1 of LMP1 gene revealed that 3 cases were XhoI- and 6 cases were XhoI+ (Fig 4). Table 4 summarized all the demographic, pathologic and genotypic data of the EBV-GC in this study.

Result of southern blot hybridization for BamHI-F region. Four specimens are seen in this figure, each sample was loaded in 2 lanes with and without enzyme, respectively from left. The first specimen was not amplified in this experiment. The other three specimens were not cleaved by Bam-HI enzyme which means they are wild-type F. (+: positive control; +/enz: positive control with enzyme; -: negative control).

Result of southern blot hybridization for BamHI-W1/I1 region. Each sample was loaded in 2 lanes with and without enzyme, respectively from left. In sample one there is no band in the second lane which suggests that the PCR product was digested but we could not detect the fragmented bands since the original band contained small number of DNA copies, so we regarded it as type "i". Samples 2, 5, and 6 are cleaved which means they are type "i". Polymorphism of samples 3 and 4 were not determined in this experiment. (+: positive control; +/enz: positive control with enzyme; -: negative control).

Result of XhoI polymorphism in southern blot hybridization. Each sample was loaded in 2 lanes with and without enzyme respectively from left. The first and the second specimens are cleaved with enzyme which means they are XhoI+. The third one is XhoI-. (+: positive control; +/enz: positive control with enzyme; -: negative control).

Discussion

The present study detected EBV-GCs in 3% of gastric carcinomas and suggested that the majority of gastric carcinomas in Iran are EBV-negative. There were no LELCs, which are well known to be strongly associated with EBV [59]. Lace pattern, which is a unique morphology in EBV-positive early gastric carcinoma [60], was not seen in our study. This frequency is among the lowest frequencies in the world. As mentioned above, according to WHO classification, the north of Iran is considered as one the regions with high gastric carcinoma frequency in the world [61]. The sparse studies in Iran also show this fact except that they show more or less homogeneity throughout the country [48, 62, 63]. Thus, the low EBV-GC frequency in Iran supports the previous hypothesis that high risk countries for GC have low rates of EBV-GC [64]. This also confirms the belief that it is low in Asia as the prevalence of 3% in Korea [25], 6% in Japan [24], 6% in china [26], 5% in India [18], 2% in Pakistan [29] and maximal 10% in Malaysia [27], Taiwan [21] and Kazakhstan [28]. However, this is much lower than Kazakhstan frequency, (our nearby country) with many similarities in the custom and socioeconomic conditions.

The prevalence of EBV-GC in diffuse type gastric carcinoma was more in our study, a fact which was seen in most of studies of Latin America [16, 32] and some countries in Asia such as Korea [25], China [26] and India [18]. However, there are many contradictory studies which did not show any relationship in this concept [15, 17, 19, 23, 33]. Koriyama et al [23] in their classic study proposed that there are many other factors which have effect on the incidence of diffuse type gastric cancer such as age, gender and location and the conflicting results in different studies could be explained by the difference in distribution of these factors.

Although the ratio of male/female was approximately 4 in our study, it was not significant in statistical analysis. The absence of gender preference was seen in other studies in Mexico [32, 37] Chile [16] and one area in China [38]. However, we should consider that the low number of positive cases in our study might be the reason of insignificant result in the analysis. Meanwhile, Koriyama et al [23] show that the gender preference for EBV is restricted to diffuse type GC and is not seen in intestinal type. Nevertheless, regarding the low number of our cases, we could not perform the analysis separately for each type.

Increase in cancer of upper portion of the stomach despite decrease in total incidence of gastric cancers is seen in many studies around the world [65, 66]. There are also many evidences that this type of gastric cancer has different risk factors [67–69]. EBV is one of them [15–31]. Abdirad et al [70] also show that there is such increase in cancer of upper third of stomach in Iran. Yet, despite our expectation, this study did not show any preference of EBV for upper or middle third of stomach. It is important to notice that in spite of many confirmatory studies in this context, there is also no such relation in our nearby countries, i.e. Kazakhstan [28] and India [18].

EBV in our study did not show any relation with age and depth of invasion. Some studies indicate that there is tendency of EBV-GC to occur in lower age [19, 26, 33, 38]. However, Koriyama et al [23] revealed that only intestinal type of EBV-GC shows this age preference, and proposed that difference in age of exposure to specific cofactors for each of these types is the probable reason.

One of the interesting findings of the present study is the fact that 6 out of our 9 EBV-GC cases which were selected randomly, were born during the period between 1928 and 1930. Although we could not perform any analysis in regard of the low number of positive cases, this finding seems important since an epidemiological study suggested that EBV infection at early childhood may be related to the development of EBV-GC in adulthood [71]. Although we have no evidence, some hypothesis could be considered. For example, specific conditions or events, leading to EBV infection in early childhood or resulting to exposure to some specific co-risk factors which might have existed around the late 1920s. Therefore, we propose a case control study focusing on gastric carcinoma in patients born around the late 1920s to compare the prevalence of EBV in these patients with the others.

Genotyping of the virus revealed that type 1 is the exclusive type in all of our EBV-GC. The predominance of type 1 is in agreement with other studies [18, 45, 58, 40]. Type 2 is mostly seen in Africa [40] and there is a belief that it is weaker than type 2 and is mostly seen in immunodeficient patients [40, 72]. The prototype F at BamHI-F was the most common type in this study. This type has a worldwide distribution except in southern China which "f" variant is prevalent and causes nasopharyngeal carcinoma [43, 45]. Our finding is the same as similar studies in gastric cancers in India [18], Japan [73], and Chile [58]. BamHI-W1/I1 region polymorphism analysis shows that 90% of our cases were type "i". Previous studies revealed that type I is the most prevalent in Asia [45, 54] and type "i" is the most in western countries [46]. This pattern of distribution had been also seen in similar studies on EBV-GC [18, 45, 73]. However, our finding seems to be similar to western countries like Corvalan findings in Colombia and Chile [58]. XhoI+ was the most prevalent type at XhoI restriction site in exon one of LMP1 gene in the present study. This finding is also similar to Corvalan finding in EBV-GC in Colombia and Chil [58] and in contrast to findings in eastern Asia [44].

The most important finding in this study was the combination of "i"/XhoI+ in 6 of our cases. Corvalan et al had shown that this combination is significantly more in EBV-GC than healthy people [58]. They propose that the existence of certain gene with transforming capacity in the vicinity of these sites is the probable explanation of more tumorigenecity of this variant. This finding is against the belief that EBV strains are geographically distributed but not disease restricted [73]. However, we need first to evaluate the genotype of EBV in healthy people in Iran before any conclusion. To our knowledge, the genotype distribution among healthy population in Iran is not reported in the literature.

Conclusion

In summary, we could say that our study is the first to describe the frequency of EBV-GC in Iran and in the Middle East, highlighting a very low prevalence. The most important feature of the present study is the fact that we could use the cases diagnosed as early as 1960. Such a feature made it possible to examine the effect of birth year. Interestingly, EBV-GC in the present study was dominated by the patients born during the period between 1928 and 1930. Most of other findings such as diffuse histology, weak male predominance and genotype of the cases were similar to studies performed in Latin America.

References

Rickinson AB, Kieff E: Epstein-Barr virus. Fields virology. Edited by: Knipe DM, Howley PM, Griffin DE, Lamb RA, Martin MA, Roizman B, Straus SE. 2001, Philadelphina, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2: 2575-2628. 4

Babcock GJ, Decker LL, Volk M, Thorley-Lawson DA: EBV persistence in memory B cells in vivo. Immunity. 1998, 9: 395-405. 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80622-6.

IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans: Epstein-Barr Virus and Kaposi's sarcoma Herpesvirus: Human Herpesvirus8. 1997, Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer

Wang F, Gregory C, Sample C, Rowe M, Liebowitz D, Murray R, Rickinson A, Kieff E: Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein (LMP1) and nuclear proteins 2 and 3C are effectors of phenotypic changes in B lymphocytes: EBNA-2 and LMP1 cooperatively induce CD23. J Virol. 1990, 64: 2309-2318.

Eliopoulos AG, Dawson CW, Mosialos G, Floettmann JE, Rowe M, Armitage RJ, Dawson J, Zapata JM, Kerr DJ, Wakelam MJ, Reed JC, Kieff E, Young LS: CD40-induced growth inhibition in epithelial cells is mimicked by Epstein-Barr virus-encoded LMP1: involvement of TRAF3 as a common mediator. Oncogene. 1996, 13: 2243-2254.

Eliopoulos AG, Stack M, Dawson CW, Kaye KM, Hodgkin L, Sihota S, Rowe M, Young LS: Epstein-Barr virus-encoded LMP1 and CD40 mediate IL6 production in epithelial cells via an NF-κB pathway involving TNF receptor-associated factors. Oncogene. 1997, 14: 2899-2916. 10.1038/sj.onc.1201258.

Komano J, Maruo S, Kurozumi K, Oda T, Takada K: Oncogenic role of Epstein-Barr virus-encoded RNAs in Burkitt's lymphoma cell line Akata. J Virol. 1999, 73: 9827-9831.

Kulwichit W, Edwards RH, Davenport EM, Baskar JF, Godfrey V, Raab-Traub N: Expression of the Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 induces B cell lymphoma in transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998, 95: 11963-11968. 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11963.

Magrath IT: African Burkitt's lymphoma. History, biology, clinical features, and treatment. Am J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1991, 13: 222-246.

Harabuchi Y, Imai S, Wakashima J, Hirao M, Kataura A, Osato T, Kon S: Nasal T-cell lymphoma causally associated with Epstein-Barr virus: clinicopathologic, phenotypic, and genotypic studies. Cancer. 1996, 77: 2137-2149. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960515)77:10<2137::AID-CNCR27>3.0.CO;2-V.

Glaser SL, Lin RJ, Stewart SL, Ambinder RF, Jarrett RF, Brousset P, Pallesen G, Gulley ML, Khan G, O'Grady J, Hummel M, Preciado MV, Knecht H, Chan JK, Claviez A: Epstein-Barr virus-associated Hodgkin's disease: epidemiologic characteristics in international data. Int J Cancer. 1997, 70: 375-382. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19970207)70:4<375::AID-IJC1>3.0.CO;2-T.

Hamilton-Dutoit SJ, Raphael M, Audouin J, Diebold J, Lisse I, Pedersen C, Oksenhendler E, Marelle L, Pallesen G: In situ demonstration of Epstein-Barr virus small RNAs (EBER 1) in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related lymphomas: correlation with tumor morphology and primary site. Blood. 1993, 82: 619-624.

Saemundsen AK, Albeck H, Hansen JP, Nielsen NH, Anvret M, Henle W, Henle G, Thomsen KA, Kristensen HK, Klein G: Epstein-Barr virus in nasopharyngeal and salivary gland carcinomas of Greenland Eskimos. Br J Cancer. 1982, 46: 721-728.

Burke AP, Yen TS, Shekitka KM, Sobin LH: Lymphoepithelial carcinoma of the stomach with Epstein-Barr virus demonstrated by polymerase chain reaction. Mod Pathol. 1990, 3: 377-380.

Shibata D, Weiss LM: Epstein-Barr virus associated gastric adenocarcinoma. American Journal of Pathology. 1992, 140: 769-774.

Corvalan A, Koriyama C, Akiba S, Eizuru Y, Backhase C, Palma M, Jorge A, Masayoshi T: Epstein-Barr virus in gastric carcinoma is associated with location in the cardia and with a diffuse histology: a study in one area of Chile. International Journal of Cancer. 2001, 94: 527-530. 10.1002/ijc.1510.

Galetsky SA, Tsvetnov VV, Land CE, Afanasieva TA, Petroricher NN, Gurtsevitch VE, Tokunaga M: Epstein-Barr virus associated gastric cancer in Russia. International Journal of Cancer. 1997, 3: 786-790. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19971210)73:6<786::AID-IJC2>3.0.CO;2-Z.

Kattoor J, Koriyama C, Akiba S, Itoh T, Ding S, Eizuru Y, Abraham EK, Chandralekha B, Amma NS, Nair MK: Epstein-Barr virus- associated gastric carcinoma in southern India: a comparison with a large-scale Japanese series. Journal of Medical Virology. 2002, 68: 384-389. 10.1002/jmv.10215.

Carrascal E, Koriyama C, Akiba S, Tamayo O, Itoh T, Eizuru Y, Garcia F, Sera M, Carrasquilla G, Piazuelo MB, Florez L, Bravo JC: Epstein-Barr virus-associated gastric carcinoma in Cali/Colombia. Oncology Reports. 2003, 10: 1059-1062.

Yoshiwara E, Koriyama C, Akiba S, Itoh T, Minakami Y, Chirinos JL, Watanabe J, Takano J, Miyagui J, Hidalgo H, Chacon P, Linares V, Eizuru Y: Epstein-Barr virus-associated gastric carcinoma in Lima, Peru. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2005, 24: 49-54.

Harn HJ, Chang JY, Wang MW, Ho LI, Lee HS, Chiang JH, Lee WH: Epstein-Barr virus-associated gastric adenocarcinoma in Taiwan. Hum Pathol. 1995, 26: 267-271. 10.1016/0046-8177(95)90056-X.

Morewaya J, Koriyama C, Akiba S, Shan D, Itoh T, Eizuru Y: Epstein-Barr virus-associated gastric carcinoma in Papua New Guinea. Oncol Rep. 2004, 12: 1093-1098.

Koriyama C, Akiba S, Corvalan A, Carrascal E, Itoh T, Herrera-Goepfert R, Eizuru Y, Tokunaga M: Histology-specific gender, age and tumor-location distributions of Epstein-Barr virus-associated gastric carcinoma in Japan. Oncol Rep. 2004, 12: 543-547.

Tokunaga M, Land CE, Uemura Y, Tanaka S, Sato E: Epstein-Barr virus in gastric carcinoma. American Journal of Pathology. 1993, 143: 1250-1254.

Chang MS, Lee HS, Kim CW, Kim YI, Kim WH: Clinicopathologic characteristics of Epstein-Barr virus-incorporated gastric cancers in Korea. Pathol Res Pract. 2001, 197: 395-400. 10.1078/0344-0338-00052.

Hao Z, Koriyama C, Akiba S, Li J, Luo X, Itoh T, Eizuru Y, Zou J: The Epstein-Barr virus-associated gastric carcinoma in Southern and Northern China. Oncol Rep. 2002, 9: 1293-1298.

Karim N, Pallesen G: Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and gastric carcinoma in Malaysian patients. Malays J Pathol. 2003, 25: 45-47.

Alipov G, Nakayama T, Nakashima M, Wen CY, Niino D, Kondo H, Pruglo Y, Sekine I: Epstein-Barr virus-associated gastric carcinoma in Kazakhstan. World J Gastroenterol. 2005, 11: 27-30.

Anwar M, Koriyama C, Naveed IA, Hamid S, Ahmad M, Itoh T, Minakami Y, Eizuru Y, Akiba S: Epstein-Barr virus detection in tumors of upper gastrointestinal tract. An in situ hybridization study in Pakistan. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2005, 24: 379-385.

Ott G, Kirchner TH, Muller-Hermelink HK: Monoclonal Epstein-Barr virus genomes but lack of EBV-related protein expression in different types of gastric carcinoma. Histopathol. 1994, 25: 323-329. 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1994.tb01350.x.

Burgess DE, Woodman CB, Flavell KJ, Rowlands DC, Crocker J, Scott K, Biddulph JP, Young LS, Murray PG: Low prevalence of Epstein-Barr virus in incident gastric adenocarcinomas from the United Kingdom. Br J Cancer. 2002, 86: 702-704. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600107.

Herrera-Goepfert R, Reyes E, Hernandez-Avila M, Mohar A, Shinkura R, Fujiyama C, Akiba S, Eizuru Y, Harada Y, Tokunaga M: Epstein-Barr virus-associated gastric carcinoma in Mexico: analysis of 135 consecutive gastrectomies in two hospitals. Modern Pathology. 1999, 12: 873-878.

Koriyama C, Akiba S, Iriya K, Yamaguti T, Hamada GS, Itoh T, Eizuru Y, Aikou T, Watanabe S, Tsugane S, Tokunaga M: Epstein-Barr virus associated gastric carcinoma in Japanese Brazilians and non-Japanese Brazilians in Sao Paulo. J Cancer Res. 2001, 92: 911-917.

Lopes LF, Bacchi MM, Elgui-de-Oliviva D, Zanati SG, Albabenga M, Bacchi CE: Epstein-Barr virus infection and gastric carcinoma in Sao Paulo state, Brazil. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Histological Research. 2004, 37: 1707-1712.

Imai S, Koizumi S, Sugiura M, Tokunaga M, Uemura Y, Yamamoto N, Tanaka S, Sato E, Osato T: Gastric carcinoma: monoclonal epithelial malignant cells expressing Epstein-Barr virus latent infection protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1994, 91: 9131-9135. 10.1073/pnas.91.19.9131.

Levine PH, Stemmermann G, Lennette ET, Hildesheim A, Shibata D, Nomura A: levated antibody titers to Epstein-Barr virus prior to the diagnosis of Epstein-Barr virus-associated gastric adenocarcinoma. Int J Cancer. 1995, 60: 642-644. 10.1002/ijc.2910600513.

Herrera-Goepfert R, Akiba S, Koriyama C, Ding S, Reyes E, Itoh T, Minakami Y, Eizuru Y: Epstein-Barr virus-associated gastric carcinoma: Evidence of age-dependence among a Mexican population. World J Gastroenterol. 2005, 11: 6096-6103.

Qiu K, Tomita Y, Hashimoto M, Ohsawa M, Kawano K, Wu DM, Aozasa K: Epstein-Barr virus in gastric carcinoma in Suzhou, China and Osaka, Japan: association with clinico-pathologic factors and HLA-subtype. Int J Cancer. 1997, 71: 155-158. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19970410)71:2<155::AID-IJC5>3.0.CO;2-#.

Rickinson A, Young L, Rowe M: Influence of the Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen EBNA 2 on the growth phenotype of virus-transformed B cells. J Virol. 1987, 61: 1310-1317.

Zimber U, Adldinger HK, Lenoir GM, Vuillaume M, Knebel-Doeberitz MV, Laux G, Desgranges C, Wittmann P, Freese UK, Schneider U, Bornkamm GW: Geographical prevalence of two types of Epstein-Barr virus. Virology. 1986, 154: 56-66. 10.1016/0042-6822(86)90429-0.

Young LS, Yao QY, Rooney CM, Sculley TB, Moss DJ, Rupani H, Laux G, Bornkamm GW, Rickinson AB: New type B isolates of Epstein-Barr virus from Burkitt's lymphoma and from normal individuals in endemic areas. J Gen Virol. 1987, 68: 2853-2862.

Lung ML, Chang RS, Huang ML, Guo HY, Choy D, Sham J, Tsao SY, Cheng P, Ng MH: Epstein-Barr virus genotypes associated with nasopharyngeal carcinoma in Southern China. Virology. 1990, 177: 44-53. 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90458-4.

Lung ML, Lam WP, Sham J, Choy D, Yong-Sheng Z, Guo HY, Ng MH: Detection and prevalence of the "f " variant of Epstein-Barr virus in Southern China. Virology. 1991, 185: 67-71. 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90754-Y.

Lung ML, Chang RS, Jones JH: Genetic polymorphism of natural Epstein-Barr virus isolates from infectious mononucleosis patients and healthy carriers. J Virol. 1988, 62: 3862-3866.

Sidagis J, Ueno K, Tokunaga M, Ohyama M, Eizuru Y: Molecular epidemiology of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) in EBV-related malignancies. Int J Cancer. 1997, 72: 72-76. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19970703)72:1<72::AID-IJC11>3.0.CO;2-C.

Abdel-Hamid M, Chen JJ, Constantine N, Massoud M, Raab-Traub N: EBV strain variation: geographical distribution and relation to disease state. Virology. 1992, 190: 168-175. 10.1016/0042-6822(92)91202-6.

Khanim F, Yao QY, Niedobitek G, Sihota S, Rickinson AB, Young LS: Analysis of Epstein-Barr virus gene polymorphisms in normal donors and in virus-associated tumors from different geographic locations. Blood. 1996, 88: 3491-3501.

Sadjadi A, Nouraie M, Mohagheghi MA, Mousavi-Jarrahi A, Malekezadeh R, Parkin DM: Cancer occurrence in Iran in 2002, an international perspective. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2005, 6: 359-363.

Lauren P: The two histological main types of gastric carcinoma, diffuse and so-called intestinal – type carcinoma. Acta Pathomicrobiol Scand. 1965, 64: 31-49.

Japanese Gastric Cancer Association: Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma. 1999, Tokyo: Kanehara 800. Ltd, 13

Chang KL, Chen YY, Shibata D, Weiss LM: Description of an in situ hybridization methodology for detection of Epstein-Barr virus RNA in paraffin-embedded tissues, with a survey of normal and neoplastic tissues. Diagn Mol Pathol. 1992, 1: 246-255. 10.1097/00019606-199203000-00037.

Greer CE, Wheeler CM, Manos MM: PCR amplification from paraffin-embedded tissues: sample preparation and the effects of fixation. PCR primer: a laboratory manual. Edited by: Carl WD, Gabriela SD. 1995, New York, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 99-112.

Sample J, Young L, Martin B, Chatman T, Kieff E, Rickinson A, Kieff E: Epstein-Barr virus Types 1 and 2 Differ in Their EBNA-3A, EBNA-3B, and EBNA-3C Genes. J Virol. 1990, 64: 4084-4092.

Lung ML, Chang GC: Detection of distinct Epstein-Barr virus genotypes in NPC biopsies from Southern Chinese and Caucasians. Int J Cancer. 1992, 52: 34-37. 10.1002/ijc.2910520108.

Hudson GS, Gibson TJ, Barrell BG: The BamHI-F region of the B95-8 Epstein-Barr virus genome. Virology. 1985, 147: 99-109. 10.1016/0042-6822(85)90230-2.

Sandvej K, Gratama JW, Munch M, Zhou XG, Bolhuis RL, Andresen BS: Sequence analysis of the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) latent membrane protein-1 gene and promoter region: identification of four variants among wild-type EBV isolates. Blood. 1997, 90: 323-330.

Wu SJ, Lay JD, Chen CL, Chen JY, Liu MY, Su IJ: Genomic analysis of Epstein-Barr virus in Nasal and Peripheral T-cell Lymphoma : a comparison with nasopharyngeal carcinoma in an endemic area. J Med Virol. 1996, 50: 314-321. 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9071(199612)50:4<314::AID-JMV6>3.0.CO;2-B.

Corvalan A, Ding S, Koriyama C, Carrascal E, Carrasquilla G, Backhouse C, Urzua L, Argandona J, Palma M, Eizuru Y, Akiba S: Association of a distinctive strain of Epstein-Barr virus with gastric cancer. Int J Cancer. 2006, 118: 1736-1742. 10.1002/ijc.21530.

Shibata D, Tokunaga M, Uemura Y, Sato E, Tanaka S, Weiss LM: Association of Epstein-Barr virus with undifferentiated gastric carcinomas with intense lymphoid infiltration. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma. Am J Pathol. 1991, 139: 469-474.

Uemura Y, Tokunaga M, Arikawa J, Yamamoto N, Hamasaki Y, Tanaka S, Sato E, Land CE: A unique morphology of Epstein-Barr virus-related early gastric carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1994, 3: 607-611.

Fenoglio-Preiser , Carneiro F, Correa P, Guilford P, Lambert R, Megraud F, Munoz N, Powell SM, Rugge M, Sasako M, Stolte M, Watanabe H: Gastric cancer. Pathology and genetics of tumors of the digestive system. Edited by: Hamilton SR, Aoltonen LA. 2000, Lyon, IARC press, 39-52.

Cancer Institute of Tehran Medical University: The final Report of national cancer registration project: presentation of a model for national cancer registration center. 2002, Teheran, The Institute

Sadjadi A, Malekzadeh R, Derakhshan MH, Sepehr A, Nouraie M, Sotoudeh M, Yazdanbod A, Shokoohi B, Mashayekhi A, Arshi S, Majidpour A, Babaei M, Mosavi A, Mohagheghi MA, Alimohammadian M: Cancer occurrence in Ardabil: results of a population-based cancer registry from Iran. Int J Cancer. 2003, 107: 113-118. 10.1002/ijc.11359.

Tokunaga M, Uemura Y, Tokudome T, Ishidate T, Masuda H, Okazaki E, Kaneko K, Naoe S, Ito M, Okamura A, Shimada A, Sato E: Epstein-Barr virus related gastric cancer in Japan, a molecular patho-epidemiological study. Acta Pathol Jpn. 1993, 43: 574-581.

Devesa SS, Blot WJ, Fraumeni JF: Changing patterns in the Incidence of esophageal and gastric carcinoma in the United States. Cancer. 1998, 83: 2049-2053. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19981115)83:10<2049::AID-CNCR1>3.0.CO;2-2.

Devesa SS, Fraumeni JF: The Rising incidence of gastric cardiac cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1999, 91: 747-749. 10.1093/jnci/91.9.747.

Chow WH, Blaser MJ, Blot WJ, Gammon MD, Vaughan TL, Risch HA, Perez-Perez GI, Schoenberg JB, Stanford JL, Rotterdam H, West AB, Fraumeni JF: An inverse relation between cagA+ strains of helicobacter pylori infection and risk of esophageal and gastric cardia adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 1998, 58: 588-590.

Terry P, Lagergren J, Hansen H, Wolk A, Nyren O: Fruit and vegetable consumption in the prevention of esophageal and cardia cancers. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2001, 10: 365-369. 10.1097/00008469-200108000-00010.

Sasazuki S, Sasaki S, Tsugane S: Cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption and subsequent gastric cancer risk by subsite and histologic type. Int J Cancer. 2002, 101: 560-566. 10.1002/ijc.10649.

Abdi-Rad A, Ghaderi-sohi S, Nadimi-Barfroosh H, Emami S: Trend in incidence of gastric adenocarcinoma by tumor location from 1969–2004: a study in one referral center in Iran. Diagnostic Pathology. 2006, 1: 5-10.1186/1746-1596-1-5.

Koriyama C, Akiba S, Minakami Y, Eizuru Y: Environmental factors related to Epstein-Barr virus-associated gastric cancer in Japan. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2005, 24: 547-553.

Sixbey J, Shirley P, Chesney P, Buntin D, Resnick L: Detection of a second widespread strain of Epstein-Barr virus. Lancet. 1989, 2: 761-765. 10.1016/S0140-6736(89)90829-5.

Fukayama M, Hayashi Y, Iwasaki Y, Chong J, Ooba T, Takizawa T, Koike M, Mizutani S, Miyaki M, Hirai K: Epstein-Barr virus-associated gastric carcinoma and Epstein-Barr virus infection of the stomach. Lab Invest. 1994, 71: 73-81.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Priority Areas of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan, No.12218231 & 17015037.

We thank Ms. Yoshie Minakami for her technical support in in situ hybridization assay and Kaveh Alavi for his kind assistance in analyzing the data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Abdirad, A., Ghaderi-Sohi, S., Shuyama, K. et al. Epstein-Barr virus associated gastric carcinoma: a report from Iran in the last four decades. Diagn Pathol 2, 25 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-1596-2-25

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-1596-2-25