Abstract

Background

The association of lichen planus with hepatitis C (HCV) has been widely reported in the literature. However, there are wide geographical variations in the reported prevalence of HCV infection in patients with lichen planus. This study was conducted to determine the frequency of hepatitis C in Iranian patients with lichen planus at Razi hospital, Tehran.

Methods

During the years 1997 and 1998, 146 cases of lichen planus, 78 (53.1%) women and 69 (46.9%) men were diagnosed. They were diagnosed on the basis of the usual clinical features and, if necessary, typical histological findings. The patients were screened for the presence of anti-HCV antibodies by third generation ELISA and liver function tests. We used the results from screening of blood donors for anti HCV (carried out by Iranian Blood Transfusion Organization) for comparison as the control group.

Results

Anti-HCV antibodies were detected in seven cases (4.8%). This was significantly higher than that of the blood donors' antibodies (p < 0.001). The odds ratio was 50.37(21.45–112.24). A statistically significant association was demonstrated between erosive lichen planus and HCV infection. Liver function tests were not significantly different between HCV infected and non-infected patients.

Conclusion

HCV apears to have an etiologic role for lichen planus in Iranian patients. On the other hand, liver function tests are not good screening means for HCV infection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Lichen planus (LP) is an idiopathic inflammatory disease with characteristic clinical and pathologic features affecting the skin, mucous membranes, nails, and hair. It is likely that both endogenous-genetic and exogenous-environmental components such as some drugs or some infection(s) may interact to elicit the disease [1]. An increased prevalence of chronic liver diseases has been reported in patients with LP, including primary biliary cirrhosis and chronic active hepatitis or cirrhosis of unknown origin [2–5]. Recently, a more widespread and chronic viral disease, hepatitis C (HCV), has been implicated in triggering LP. While some studies of selected populations with LP have confirmed a significant association with HCV [3, 6–9], other investigations have failed to document this finding [10–14]. This study was conducted to determine the frequency of hepatitis C in patients with LP at Razi hospital, in Tehran, Iran.

Methods

In this case-control study 146 cases of LP were selected using simple non-random (sequential) sampling. The study was conducted during 1997 and 1998. Diagnosis of LP was made by clinical observation and in suspicious cases, diagnosis was confirmed by biopsy. Patients suspected of drug-induced lichenoid eruptions, were not included.

The demographic data such as age, gender, duration of illness and other pieces of information including type of lesions, sites of involvement and patients' symptoms were collected using a checklist after the patients' consent.

Hepatitis C antibody titer was measured by third generation Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (Ortho® HCV 3.0 ELISA Test System; Ortho-Clinical Diagnostics, Raritan, NJ, USA). We used the prevalence of HCV antibody among 319375 volunteer blood donors (1996–1998) for comparison as the control group [15]. Liver function tests were also performed (Shimanzym-Iran).

Serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels ranging between 5 to 40 IU/lit, alkaline phosphatase levels 70 to 306 IU/lit and bilirubin concentrations below 1.4 mg/dl were assumed as normal.

The collected data were analyzed using SPSS (ver.10) software. Mean age, duration of illness and laboratory tests were compared between LP patients with and without hepatitis C by using T-test. HCV antibody frequency was compared in different groups using the chi-square test.

Results

Seven patients (4.8%) out of 146 had positive titer for anti-HCV antibody. When compared to the control group the odds ratio was 50.37(21.45–112.24). The clinical and laboratory characteristics of these patients are detailed in table 1.

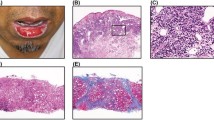

The mean age of the patients in this study was 40.8 ± 15.7 years (patients were from ages 8–76). Sixty nine patients (46.9%) were male and 78(53.1%) were female. Sites of LP involvement were: skin in 137 patients (93.2%), mucous membrane in 61 patients (41.5%), and nails in 28 patients (19.2%). Pruritus was seen in 124 patients (90.5%).

The observed lesion types were as follows: nonerosive mucosal in 57 patients (39%), hypertrophic in 45 patients (30.6%), annular in 39 patients (26.5%), folicullar in 37 patients (25.2%), nonerosive palmoplantar in 29 patients(19.9%), nail lesions in 28 patients (19.2%), atrophic in 14 patients (9.5%), erosive mucosal lesions in 11 patients (7.5%), guttate form in 14 patients (9.5%), actinic in 7 patients (4.8%) and erosive palmoplantar lesions in 1 patient (0.7%).

In 11 patients (7.5%) serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels were higher than normal and high levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) were detected in 21 patients (14.3%). Higher levels of alkaline phosphatase were observed in 7 (4.8%) patients. Five patients (3.4%) had bilirubin concentrations higher than the normal range.

Eight patients mentioned a history of blood transfusion, 4 in LP patients with HCV and 4 in those without HCV. The history of transfusion was significantly higher in hepatitis C group (P < 0.001).

Discussion

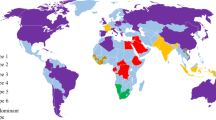

In recent years, both mucosal and cutaneous lichen planus have been reported to occur in the setting of chronic HCV infection [14]. However, there are wide geographical variations in the reported prevalence of HCV infection in patients with LP, varying from 0% in England [16] to 63% in Japan [17]. The available reports indicate that the prevalence of HCV antibodies in patients with mucosal and cutaneous LP is significantly higher than that of the control populations (non-LP dermatologic patients or population of blood donors) in Germany[8], Italy[18], Spain[3, 9], the USA and Japan,[14]suggesting an etiologic role for HCV in LP. However studies in France [11, 12] and England [11, 13, 16] could not demonstrate a statistically significant association between HCV and LP. Erkek et al [14] found that HCV antibody prevalence in Turkish patients with LP (12.9%) was higher than that of the control group (3.7%) but the difference was not statistically significant, whereas Kirtek et al [7] found statistically significant difference in Gaziantep region of Turkey.

According to our study HCV antibody prevalence in Iranian patients with LP was 4.8%. It was significantly higher than anti-HCV antibody prevalence in blood donors (0.1%), used as control group (P < 0.001). To our knowledge, there is no previous study evaluating the prevalence of anti-HCV in Iranian LP patients.

In our cases GOT was higher than the normal range in 11(7.5%) patients, none of them were HCV infected. A high level of alkaline phosphatase was measured in 14 (9.5%) patients. The bilirubin concentration was abnormal in 7% of cases. There was no significant difference in liver function tests between HCV infected and non infected groups.

As expected, there were significantly more cases with positive transfusion history among hepatitis C affected group (P < 0.001).

Type of LP and lesional location did not differ between the two groups. As with other studies [3, 9, 18], mucosal erosions were more common in hepatitis C patients (p < 0.001).

The pathogenic role of HCV in the development of LP is still unclear. For some authors the association of LP and positive serology for HCV, even positive RNA is not a substantive enough reason to determine the role of HCV in the pathogenesis of LP. Nevertheless, demonstration of HCV RNA in epithelial cells of oral mucosa [19, 20] and skin lesions [14] of patients with LP would lead to the theory that direct action of the virus is involved. HCV could be a potential antigen presented by Langerhans cells, followed by activation and migration of lymphocytes resulting in damage to basal cells via cytockines of cytotoxic T cells [21, 18]. The virus may alter epithelial antigenicity at sites of mucocutaneous replication leading either to direct activation of cytotoxic T cells [13, 21] or to production of antibodies against epithelial antigens [23]. Recently, Petruzzi et al [24] demonstrated differences in lymphocyte subpopulations between HCV positive oral LP patients and HCV negative patients with oral LP. They attributed this to the chronic antigenic stimulation of HCV. On the other hand, the different results in previous studies and the differences in respect to the geographic area could be in relation to the different genetic susceptibility of the hosts. Carrozzo et al [25] have suggested that genetic polymorphism of interferon-gamma and tumor necrosis factor-alpha may contribute to the development of oral and orocutaneous involvement, respectively.

Conclusions

It seems that screening for anti-HCV antibody is valuable in LP patients, even in those with normal liver function tests.

References

Daoud MS, Pitteikow MR: Lichen Planus. In: Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine 5 Edition Newyork; McGraw-Hill 1999, 1: 562.

Mokni M, Rybojad M, Puppin D Jr, Catala S, Venezia F, Djian R, Morel P: Lichen planus and hepatitis C virus. J AM Acad Dermatol 1991, 24: 792.

Sanchez-Perez J, De Castro M, Buezo GF, Fernandez-Herrera J, Borque MJ, Garcia-Diez A: Lichen planus and hepatitis C virus: Prevalence and clinicalpresentation of patients with Lichen planus and hepatitis C virus infection. Br J Dermatol 1996, 134: 715–9.

Bellman B, Reddy R, Falanga V: Generalized Lichen planus associated with hepatitis C virus immunoreactivity. J Am Acad Dermatol 1996, 35: 770–2.

Jubert C, Pawlotsky J-M, Pouget F, Andre C, DeForges L, Bretagne S, Mavier JP, Duval J, Revuz J, Dhumeaux D, Bagot M: Lichen planus and hepatitis C virus-related chronic active hepatitis. Arch Dermatol 1994, 130: 73–6. 10.1001/archderm.130.1.73

Chuang TY, Stitle L, Brashear R, Lewis C: Hepatitis C virus and lichen planus: A case-control study of 340 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 1999, 41: 787–9.

Kirtak N, Inaloz HS, Ozgoztasi , Erbagci Z: The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in patients with lichen planus in Gaziantep region of Turkey. Eur J Epidemiol 2000, 16: 1159–61. 10.1023/A:1010968309956

Imhof M, Popal H, Lee J-H, Zeuzem S, Milberadt R: Prevalence of hepatitis C virus antibodies and evaluation of hepatitis C virus genotypes in patients with lichen planus. Dermatology 1997, 195: 1–5.

Gimenez-Garcia R, Perez-Castrillon JL: Lichen planus and hepatitis C virus infection. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2003, 17: 291–25. 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2003.00839.x

Daramola OOM, George AO, Ogunbiyi AO: Hepatitis C virus and lichen planus in Nigerians: any relationship? Int J Dermatol 2002, 41: 217–9. 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2002.01465.x

Cribier B, Garnier C, Laustriat D, Heid E: Lichen planus and hepatitis C virus infection: An epidemiologic study. J Am Acad Dermatol 1994, 31: 1070–2.

Dupin N, Chosidow O, Lunel F, Fretz C, Szpirglas H, Frances C: Oral lichen planus and hepatitis C virus infection: a fortuitous association? Arch Dermatol 1997, 133: 1052–3. 10.1001/archderm.133.8.1052

Tucker SC, Coulson IH: Lichen planus is not associated with hepatitis C virus infection in patients from North West England. Acta Derm Venereol 1999, 79: 378–9. 10.1080/000155599750010328

Erkek E, Bozdogan O, Olut AI: Hepatitis C virus infection prevalence in lichen planus: examination of lesional and normal skin of hepatitis C virus-infected patients with lichen planus for the presence of hepatitis C virus RNA. Clin Exp Dermatol 2001, 26: 540–4. 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2001.00885.x

Alavian SM, Gholami B, Masarrat S: Hepatitis C risk factors in Iranian volunteer blood donors: A case-control study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2002, 17: 1092–97. 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2002.02843.x

Ingafou M, Porter SR, Scully C, Teo CG: No evidence of HCV infection or liver disease in British patients with oral lichen planus. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1998, 27: 65–6.

Nagao Y, Sata M, Tanikava K, Itoh K, Kameyama T: Lichen planus and hepatitis C virus in the Northern Kyushu region of Japan. Eur J Clin Invest 1995, 25: 910–914.

Carrozzo M, Gandolfo S, Carbone M, Colombatto P, Broccoletti R, Garzino-Demo P, Ghisetti V: Hepatitis C virus infection in Italian patients with oral lichen planus: a prospective case-control study. J Oral Pathol Med 1996, 25: 527–33.

Carrozzo M, Gandolfo S, Carbone M, Colombatto P, Broccoletti R, Garzino-Demo P, Ghisetti V: Hepatitis C virus infection in Italian patients with oral lichen planus: a prospective case-control study. J Oral Pathol Med 1996, 25: 527–33.

Arrieta JJ, Rodriguez Inigo E, Casqueiro M, Bartolom J, Manzarbeitia F, Herrero M, Pardo M, Carreno V: Detection of hepatitis C virus replication by in situ hybridization in epithelial cells of anti-hepatitis C virus-positive patients with and without oral lichen planus. Hepatology 2000, 32: 97–103. 10.1053/jhep.2000.8533

Nagao Y, Kameyama T, Sata M: Hepatitis C virus RNA detection in oral lichen planus tissue. Acta Derm Venereol 1998, 78: 355–7. 10.1080/000155598443051

Lapidoth M, Arber N, Ben-Amitai , Hagler J: Successful Interferon Treatment for Lichen Planus Associated with Chronic Active Hepatitis due to Hepatitis C Virus Infection. Acta Derm Venereol 1997, 77: 171–2.

Lodi G, Olsen I, Piattelli A, D'Amico E, Artese L, Porter SR: Antibodies to epithelial components in oral lichen planus (OLP) associated with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. J Oral Pathol Med 1997, 26: 36–9.

Petruzzi M, De Bebedittis M, Loria MP, Dambra P, D'Oronzio L, Capuzzimati C, Tursi A, Lo Muzio L, Serpico R: Immune response in patients with oral lichen planus and HC infection. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol 2004, 17: 93–98.

Carrozzo M, Uboldi de Capai M, Dametto E, Fasano ME, Arduino P, Broccoletti R, Vezza D, Rendine S, Curtoni ES, Gandolfo S: Tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interferon-gamma polymorphisms contribute to susceptibility to oral lichen planus. J Invest Dermatol 2004, 122: 87–94.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-5945/4/6/prepub

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

None declared.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally in the study design, literature search, data analysis and manuscript preparation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Ghodsi, S.Z., Daneshpazhooh, M., Shahi, M. et al. Lichen planus and Hepatitis C: a case-control study. BMC Dermatol 4, 6 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-5945-4-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-5945-4-6