Abstract

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) acts as an endotoxin, releases inflammatory cytokines, and promotes an inflammatory response in various tissues. This study investigated whether LPS modulates neuroglia activation and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB)-mediated inflammatory factors in the cerebral cortex. Adult male mice were divided into control animals and LPS-treated animals. The mice received LPS (250 μg/kg) or vehicle via an intraperitoneal injection for 5 days. We confirmed a reduction of body weight in LPS-treated animals and observed severe histopathological changes in the cerebral cortex. Moreover, we elucidated increases of reactive oxygen species and oxidative stress levels in LPS-treated animals. LPS administration led to increases of ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule-1 (Iba-1) and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) expression. Iba-1 and GFAP are well accepted as markers of activated microglia and astrocytes, respectively. Moreover, LPS exposure induced increases of NF-κB and pro-inflammatory factors, such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α). Increases of these inflammatory mediators by LPS exposure indicate that LPS leads to inflammatory responses and tissue damage. These results demonstrated that LPS activates neuroglial cells and increases NF-κB-mediated inflammatory factors in the cerebral cortex. Thus, these findings suggest that LPS induces neurotoxicity by increasing oxidative stress and activating neuroglia and inflammatory factors in the cerebral cortex.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is known as a lipoglycan and endotoxin that is found in the outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria. LPS administration induces cognitive impairment and behavioral depression [1, 2]. It also exacerbates the extent of brain damage after an experimental stroke [3]. Moreover, it induces neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration in mice by stimulating pro-inflammatory cytokines [4, 5]. LPS increases oxidative stress, releases inflammatory cytokines, and induces inflammatory response [6, 7]. Inflammation is a complex biological response against harmful stimuli such as pathogens. It performs a critical role in removing the initial cause of cell injury, clearing out damaged cells, and initiating tissue repair. Ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1 (Iba-1) is a calcium/actin-binding protein that is specifically expressed in macrophages and microglia [8]. Iba-1 is induced by cytokines and interferons and is involved in the inflammatory response [9]. Moreover, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) is an intermediate filament protein that is mainly expressed in astrocytes [10]. It is involved in many important central nervous system processes, including cell motility and blood-brain barrier formation [11, 12]. Thus, Iba-1 and GFAP are accepted as markers of microglia and astrocytes.

Nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) is a protein complex that controls cytokine production and cell survival [13]. NF-κB regulates cellular processes including cell proliferation, apoptosis, and inflammatory response [14,15,16]. It is involved in cellular responses to stimuli, such as free radicals, cytokines, and bacterial or viral antigens [17,18,19]. Moreover, NF-κB has pro-inflammatory properties. It induces gene expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin 1 β (IL-1β) and tumor necrosis factor- α (TNF-α). IL-1β is a member of the interleukin 1 family of cytokines [20]. TNF-α is a member of the tumor necrosis factor superfamily, which is a cytokine involved in systemic inflammation [21]. These cytokines are produced by activated macrophages and are involved in various cellular activities, including cell differentiation, proliferation, and apoptosis [22,23,24,25]. Moreover, these cytokines are well known as important mediators of the inflammatory response. We propose that LPS can lead to an inflammatory response through regulation of NF-κB, IL-1β, and TNF-α in the cerebral cortex. Thus, we investigated whether LPS modulates activations of neuroglial cells and NF-κB mediated inflammatory factors in the cerebral cortex of adult mice.

Materials and methods

Experimental animal and drug treatment

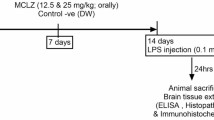

Male BALB/c mice (6 weeks, 33–35 g, n = 30) were supplied from Samtako Co. (Animal Breeding Centre, Osan, Korea). All animal experiments were performed in accordance with guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Gyeongsang National University. Mice were housed in controlled temperature (25 ± 2 °C) with a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle and provided with free access to feed and water. Animals were randomized into control and LPS-treated groups. LPS (250 μg/kg, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was dissolved in normal saline and intraperitoneally injected for 5 days [26, 27]. Control animals were administered with the same volume of normal saline. Body weights of mice were measured on every morning and mice were sacrificed at 24 h after last injection. Brain tissues were separated from skull and fixed in 4% formaldehyde for histological analysis. Moreover, cerebral cortices were quickly isolated from brain and stored at − 70 °C for reactive oxygen species (ROS), lipid peroxidation, and Western blot analyses.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) assay

Cerebral cortices were homogenized in lysis buffer [1% Triton X-100, 1 mM EDTA in phosphate buffer saline (PBS, pH 7.4)] and centrifuged at 15,000 g for 20 min. Supernatants were isolated and protein concentration was measured with bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein analysis kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). Samples were diluted with Locke’s buffer [154 mM NaCl, 5.6 mM KCl, 3.6 mM NaHCO3, 2.0 mM CaCl2, 10 mM D-glucose, and 5 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid] at 5 mg/ml. 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA, Sigma Aldrich), which can be oxidized into fluorescent dichlorofluorescein (DCF), was used to detect the formation of ROS. Diluted samples were blended into 5 mM DCFH-DA and incubated for 15 min at room temperature. ROS generations were observed at excitation wavelength 484 nm and emission wavelength 530 nm using a spectrofluorimeter. ROS analysis was expressed as DCF pmol/mg of protein. ROS value of control group was set to 1.

Lipid peroxidation (LPO) assay

LPO assay was measured with malondialdehyde (MDA) that is production of lipid peroxidation. It was followed by manufacturer’s instruction (BioVision Inc., Milpitas, CA, USA). Cerebral cortices were homogenized with MDA lysis buffer and butylated hydroxytoluene on ice. Samples were centrifuged in 13,000 g for 10 min to remove insoluble material and supernatants were collected. Supernatants were incubated with thiobarbituric acid at 95 °C for 60 min and cooled in ice for 10 min. Absorbance of supernatants were read at 532 nm and MDA amount was expressed as nmol/mg of protein. MDA value of control group was set to 1.

Hematoxylin and eosin staining

Fixed brain tissues were washed with tap water for overnight, dehydrated by gradient of ethyl alcohol from 70 to 100%, and cleaned with xylene. Tissues were embedded with paraffin using embedding center (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany), sectioned into 4 μm coronal section on a rotary microtome (Leica), placed on slide glass, and dried on a slide warmer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Sections were depaffinized with xylene, rehydrated by gradient of ethyl alcohol from 100 to 70%, and stained with Harris’ hematoxylin solution (Sigma-Aldrich) and eosin Y solution (Sigma Aldrich). Stained sections were dehydrated by gradient of ethyl alcohol from 70 to 100%, cleaned with xylene, and mounted with permount mounting solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific). They were observed and photographed with Olympus microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Western blot analysis

Protein samples of cerebral cortices were extracted with lysis buffer [1% Triton X-100, 1 mM EDTA in 1 × PBS (pH 7.4)] containing 200 μM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and centrifuged at 15,000 g for 20 min. Supernatants were collected and protein concentrations were measured using a BCA protein analysis kit (Pierce). Protein samples (30 μg) were denatured for 3 min at 100 °C, incubated in ice for 1 min, and electrophoresed in 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate poly-acrylamide gels. Loaded samples were transferred to polyvinylidenedifluoride membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). Membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk solution diluted in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween-20 (TBST) for 1 h and washed with TBST. After washing, membranes were incubated for overnight at 4 °C with following primary antibody: anti-Iba-1, anti-GFAP, anti-NF-κB, anti-TNF-α, anti-IL-1β, and anti-β-actin (anti-Iba-1, anti-GFAP, anti-NF-κB, anti-TNF-α, anti-IL-1β, and anti-β-actin primary antibody, diluted 1:1000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA). Membranes were washed with TBST and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG or anti-rabbit IgG (1:5000, Cell Signaling Technology) for 2 h at room temperature. After washing with TBST, membranes were reacted with enhanced chemiluminescence detection reagents (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, UK) for detecting immunoreactive protein bands and exposed to Fuji medical X-ray film (Fuji Film, Tokyo, Japan).

Immunofluorescence staining

Paraffin sections were deparaffinied with xylene and rehydrated by gradient of ethyl alcohol from 100 to 70%. Sections were washed with PBS and reacted with normal goat serum for 1 h for blocking non-specific reaction. Sections were incubated in a wet chamber for overnight at 4 °C with following primary antibodies: anti-Iba-1, anti-GFAP, anti-NF-κB, anti-TNF-α, and anti-IL-1β (anti-Iba-1, anti-GFAP, anti-NF-κB, anti-TNF-α, and anti-IL-1β primary antibody, diluted 1:100, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Sections were washed with PBS and incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-mouse IgG or anti-rabbit IgG (1:200, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 2 h at room temperature. Sections were reacted with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Sigma Aldrich) for 10 min and mounted with Ultra-Cruz mounting medium (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Fluorescent signals were observed and imaged with a confocal microscope (FV-1000, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Integrated intensities of positive signals were analyzed by Image-Pro Plus image software (Media Cybernetics, Rockville, MD, USA). Intensity values were expressed as a ratio of LPS-treated group intensity to control group intensity. Intensity value of control group was set to 1.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard error of mean (S.E.M.). Results of group were compared by Student’s t-test. A value of p < 0.05 was statistically considered significant.

Results

LPS treatment induced a significant decrease of body weight (Fig. 1a). Body weights were 29.1 ± 0.98 and 36.7 ± 1.24 in control and LPS-treated animals, respectively, at 24 h after last injection. ROS and LPO values were measured as DCF and MDA levels, respectively. They were significantly increased in LPS-treated animals compare with those of control animals. DCF and MDA levels of control animals were set to 1. DCF and MDA levels in LPS-treated animals were 1.97 ± 0.33 and 2.21 ± 0.22, respectively (Fig. 1b). Figure 1c showed the histopathological changes in cerebral cortices after LPS exposure. Neuronal and neuroglial cells with normal morphology were observed in control animals. Most of the neurons had a typical pyramid shape with well-characterized dendrites (Fig. 1c and e). However, we observed severe histological changes in LPS-treated animals. Most of the nerve cells were swollen, with loss of their processes, surrounded by pericellular halos, and vacuolated (Fig. 1d and f). Neuroglial cells were shrunken and deeply stained (Fig. 1f).

Body weight (a), reactive oxygen species (ROS) and lipid peroxidation (LPO) analyses (b), and representative photomicrographs of hematoxylin and eosin staining (c-f) in the cerebral cortices of control and lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-treated animals. LPS induced a reduction of body weight (a) and increases of DCF and MDA values (b). LPS treatment induced severe histopathological changes including swelling and vacuolation of nerve cells (d and f). Arrows indicate normal pyramidal cells with well-characterized dendrites (e). Open arrows indicate abnormal nerve cells that were swollen and vacuolated (f). Arrowheads indicate shrunken neuroglial cells (f). Magnified photos indicate square region. Scale bar = 100 μm (c and d), 200 μm (e and f). Data (n = 5) are shown as mean ± S.E.M. # p < 0.05 vs. control animal

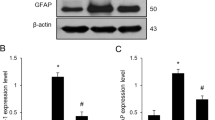

Iba-1 and GFAP expressions were investigated to elucidate activation of microglia and astrocytes. Western blot analysis showed that Iba-1 and GFAP expression levels were increased in LPS-treated animals (Fig. 2a). Iba-1 expression levels were 0.57 ± 0.02 in control animals and 0.93 ± 0.04 in LPS-treated animals. GFAP levels were 0.43 ± 0.01 and 0.75 ± 0.04 in control and LPS-treated animals, respectively (Fig. 2b). Moreover, immunofluorescence staining showed that Iba-1 and GFAP positive reactions increased in LPS-treated animals (Fig. 3a and b). Iba-1 and GFAP expression values were measured as a ratio of the intensity of control animals. Iba-1 and GFAP expression values in LPS-treated animals were 4.02 ± 0.44 and 3.21 ± 0.39, respectively (Fig. 3c).

Western blot analysis of ionized calcium binding adaptor molecule-1 (Iba-1) and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) in cerebral cortices of control and lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-treated animals (a). Density values of Western blot analysis are expressed as a ratio of each protein intensity to β-actin intensity (b). Data (n = 5) are shown as mean ± S.E.M. # p < 0.05 vs. control animal

Double immunofluorescence labeling of ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule-1 (Iba-1) and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) in cerebral cortices of control and lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-treated animals (a and b). Scale bar = 100 μm. Intensity values of fluorescence were expressed as ratio of intensity of LPS-treated to intensity of control animals (c). Intensity value of control animal was set to 1. Data (n = 5) are shown as mean ± S.E.M. # p < 0.05 vs. control animal

Figure 4a shows increases of NF-κB, IL-1β, and TNF-α in the cerebral cortices of LPS-treated animals. NF-κB levels were 0.32 ± 0.07 and 0.71 ± 0.04 in control animals and LPS-treated animals, respectively. IL-1β levels were 0.22 ± 0.08 in control animals and 0.87 ± 0.07 in LPS-treated animals. TNF-α levels were 0.55 ± 0.05 and 0.92 ± 0.06 in control animals and LPS-treated animals, respectively (Fig. 4b). Results of immunofluorescence staining confirmed increases of these proteins in LPS-treated animals (Fig. 5a-c). NF-κB was expressed in neuronal cell bodies and brain capillary cells and expression value was 4.47 ± 0.56 in LPS-treated animals. IL-1β and TNF-α was expressed in neuronal cell bodies expression values in LPS-treated animals were 4.40 ± 0.41 and 5.21 ± 0.23, respectively (Fig. 5d).

Western blot analysis of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) in the cerebral cortex of control and lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-treated animals (a). Density values of Western blot analysis are expressed as a ratio of each protein intensity to β-actin intensity (b). Data (n = 5) are shown as mean ± S.E.M. # p < 0.05 vs. control animal

Double immunofluorescence labeling of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) in the cerebral cortex of control and lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-treated animals (a-c). Scale bar = 100 μm. Intensity values of fluorescence were expressed as ratio of intensity of LPS-treated animals to intensity of control animals (d). Intensity value of control animals was set to 1. Data (n = 5) are shown as mean ± S.E.M. # p < 0.05 vs. control animal

Discussion

We clearly showed a reduction of body weight and histopathological changes such as, vacuolation, swollen cell body, and weakly stained cells in the cerebral cortex after LPS-induced neuroinflammation. Moreover, LPS induces over-production of oxidative stress and activation of neuroglia and leads to inflammatory response via NF-κB mediated inflammatory factors including IL-1β and TNF-α in cerebral cortex. We focused on activations of neuroglial cells and inflammatory mediators after LPS exposure in the cerebral cortex.

LPS activates astrocytes and microglia [28, 29]. Activated microglia release pro-inflammatory mediators and nitric oxide synthase, and lead to neuronal cells damage in degenerative disease [30, 31]. Moreover, oxidative stress leads to the release of inflammatory cytokines and nitric oxide from monocytes and macrophages. In this study, we assessed LPS-induced oxidative injury by ROS and lipid peroxidation analyses. We showed increases of DCF and MDA levels in the cerebral cortex after LPS exposure. LPS induces a decrease in membrane potential and an impairment in mitochondrial redox activity, leading to neuronal dysfunction and degeneration [32, 33]. Moreover, it also induces amyloid deposits and cognitive impairments [34, 35]. Our results showed that LPS activates microglia and astrocytes in the cerebral cortex and induces neuroinflammation. We observed increases of Iba-1 and GFAP expression in an LPS-treated cerebral cortex. Iba-1 and GFAP are used as indicators of activated microglia and astrocyte. Ibal-1 is up-regulated in microglia during nerve injury [36]. This study clearly showed an increase of Ibal-1 expression in damaged cerebral cortex caused by LPS exposure. Up-regulation of Ibal-1 indicates activation of microglia. Moreover, GFAP expression increases in central nervous system injury, neurodegenerative disease, and aging [37,38,39]. Increase of GFAP expression is also observed in neuroinflammatory disease [40]. Our results are in accordance with data of previous studies. We showed up-regulation of GFAP in the cerebral cortex of LPS-treated animals. Increase of GFAP demonstrates activation of astrocytes and activated neuroglial cells leads to release of inflammatory cytokines. These processes induce inflammatory response and ultimately lead to cell damage.

LPS treatment causes the activation of inflammatory mediators and leads to inflammatory responses. NF-κB releases pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β. This study showed increases of NF-κB, TNF-α, and IL-1β in a damaged cerebral cortex caused by LPS exposure. Activated NF-κB up-regulates pro-inflammatory cytokines, IL-1β and TNF-α. These cytokines participate in the progression of liver and lung injuries [41]. They were up-regulated in injuries. Moreover, IL-1β augments TNF-α-mediated inflammatory response [42]. TNF-α is related to excitotoxic and neuroinflammatory processes that occur in neurodegenerative disease such as ischemia and traumatic brain injury [43, 44]. We showed that LPS induces up-regulation of IL-1β and TNF- α in the cerebral cortex, and increases of these pro-inflammatory factors cause inflammatory responses. Our results demonstrated that LPS increases oxidative stress and activates neuroglial cells including microglia and astrocytes in the cerebral cortex. Moreover, LPS up-regulates NF-κB-mediated inflammatory factors such as IL-1β and TNF-α in the cerebral cortex. Previous studies reported that LPS mediates to neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration in the cerebral cortex of adult mice via the Akt/GSK-3β survival pathway [45, 46]. The LPS-mediated mechanism is very complex. Neuroinflammatory responses caused by LPS occur through various cell-signaling pathways. This study elucidated that LPS mediates inflammatory responses via NF-κB activation in the cerebral cortex.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that LPS administration induces neurotoxicity and neuroinflammation through activating neuroglia and NF-κB-mediated inflammatory factors in the cerebral cortex of adult mice. Therefore, this finding might provide a basic information about neuroinflammation induced by systemic LPS administration.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BCA:

-

Bicinchoninic acid

- DAPI:

-

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- DCF:

-

Dichlorofluorescein

- DCFH-DA:

-

2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate

- FITC:

-

Fluorescein isothiocyanate

- GFAP:

-

Glial fibrillary acidic protein

- Iba-1:

-

Ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule-1

- IL-1β:

-

Interleukin-1β

- LPO:

-

Lipid peroxidation

- LPS:

-

Lipopolysaccharide

- MDA:

-

Malondialdehyde

- NF-κB:

-

Nuclear factor kappa B

- NRF:

-

National research foundation of Korea

- PBS:

-

Phosphate buffer saline

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species

- TBST:

-

Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween-20

- TNF-α:

-

Tumor necrosis factor-α

References

Yirmiya R. Endotoxin produces a depressive-like episode in rats. Brain Res. 1996;711(1–2):163–74.

Zhao J, Bi W, Xiao S, Lan X, Cheng X, Zhang J, Lu D, Wei W, Wang Y, Li H, Fu Y, Zhu L. Neuroinflammation induced by lipopolysaccharide causes cognitive impairment in mice. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):5790.

McColl BW, Rothwell NJ, Allan SM. Systemic inflammation alters the kinetics of cerebrovascular tight junction disruption after experimental stroke in mice. J Neurosci. 2008;28(38):9451–62.

Gabellec MM, Griffais R, Fillion G, Haour F. Expression of interleukin 1 alpha, interleukin 1 beta and interleukin 1 receptor antagonist mRNA in mouse brain: regulation by bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) treatment. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1995;31(1–2):122–30.

Buttini M, Mir A, Appel K, Wiederhold KH, Limonta S, Gebicke-Haerter PJ, Boddeke HW. Lipopolysaccharide induces expression of tumour necrosis factor alpha in rat brain: inhibition by methylprednisolone and by rolipram. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;122(7):1483–9.

Nolan Y, Vereker E, Lynch AM, Lynch MA. Evidence that lipopolysaccharide-induced cell death is mediated by accumulation of reactive oxygen species and activation of p38 in rat cortex and hippocampus. Exp Neurol. 2003;184(2):794–804.

Quan N, Stern EL, Whiteside MB, Herkenham M. Induction of pro-inflammatory cytokine mRNAs in the brain after peripheral injection of subseptic doses of lipopolysaccharide in the rat. J Neuroimmunol. 1999;93(1–2):72–80.

Imai Y, Ibata I, Ito D, Ohsawa K, Kohsaka S. A novel gene iba1 in the major histocompatibility complex class III region encoding an EF hand protein expressed in a monocytic lineage. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;224(3):855–62.

Utans U, Arceci RJ, Yamashita Y, Russell ME. Cloning and characterization of allograft inflammatory factor-1: a novel macrophage factor identified in rat cardiac allografts with chronic rejection. J Clin Invest. 1995;95(6):2954–62.

Jacque CM, Vinner C, Kujas M, Raoul M, Racadot J, Baumann NA. Determination of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) in human brain tumors. J Neurol Sci. 1978;35(1):147–55.

Elobeid A, Bongcam-Rudloff E, Westermark B, Nistér M. Effects of inducible glial fibrillary acidic protein on glioma cell motility and proliferation. J Neurosci Res. 2000;60(2):245–56.

Pekny M, Stanness KA, Eliasson C, Betsholtz C, Janigro D. Impaired induction of blood-brain barrier properties in aortic endothelial cells by astrocytes from GFAP-deficient mice. Glia. 1998;22(4):390–400.

Gilmore TD. Introduction to NF-kappaB: players, pathways, perspectives. Oncogene. 2006;25(51):6680–4.

Brantley DM, Chen CL, Muraoka RS, Bushdid PB, Bradberry JL, Kittrell F, Medina D, Matrisian LM, Kerr LD, Yull FE. Nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-kappaB) regulates proliferation and branching in mouse mammary epithelium. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12(5):1445–55.

Dutta J, Fan Y, Gupta N, Fan G, Gélinas C. Current insights into the regulation of programmed cell death by NF-kappaB. Oncogene. 2006;25(51):6800–16.

Monaco C, Andreakos E, Kiriakidis S, Mauri C, Bicknell C, Foxwell B, Cheshire N, Paleolog E, Feldmann M. Canonical pathway of nuclear factor κB activation selectively regulates proinflammatory and prothrombotic responses in human atherosclerosis. Oncogene. 2004;101(15):5634–9.

Brasier AR. The NF-kappaB regulatory network. Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2006;6(2):111–30.

Hiscott J, Nguyen TL, Arguello M, Nakhaei P, Paz S. Manipulation of the nuclear factor-kappaB pathway and the innate immune response by viruses. Oncogene. 2006;25(51):6844–67.

Siomek A. NF-κB signaling pathway and free radical impact. Acta Biochim Pol. 2012;59(3):323–31.

Quan N, Sundar SK, Weiss JM. Induction of interleukin-1 in various brain regions after peripheral and central injections of lipopolysaccharide. J Neuroimmunol. 1994;49(1–2):125–34.

Strieter RM, Kunkel SL, Bone RC. Role of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in disease states and inflammation. Crit Care Med. 1993;21(10):S447–63.

Parameswaran N, Patial S. Tumor necrosis factor-α signaling in macrophages. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2010;20(2):87–103.

Rath PC, Aggarwal BB. TNF-induced signaling in apoptosis. J Clin Immunol. 1999;19(6):350–64.

Wang X, Fu S, Wang Y, Yu P, Hu J, Gu W, Xu XM, Lu P. Interleukin-1beta mediates proliferation and differentiation of multipotent neural precursor cells through the activation of SAPK/JNK pathway. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2007;36(3):343–54.

Wang XJ, Kong KM, Qi WL, Ye WL, Song PS. Interleukin-1 beta induction of neuron apoptosis depends on p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activity after spinal cord injury. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2005;26(8):934–42.

Guo S, Al-Sadi R, Said HM, Ma TY. Lipopolysaccharide causes an increase in intestinal tight junction permeability in vitro and in vivo by inducing enterocyte membrane expression and localization of TLR-4 and CD14. Am J Pathol. 2013;182(2):375–87.

Lee JW, Lee YK, Yuk DY, Choi DY, Ban SB, Oh KW, Hong JT. Neuro-inflammation induced by lipopolysaccharide causes cognitive impairment through enhancement of beta-amyloid generation. J Neuroinflammation. 2008;5:37.

Chen Z, Jalabi W, Shpargel KB, Farabaugh KT, Dutta R, Yin X, Kidd GJ, Bergmann CC, Stohlman SA, Trapp BD. Lipopolysaccharide-induced microglial activation and neuroprotection against experimental brain injury is independent of hematogenous TLR4. J Neurosci. 2012;32(34):11706–15.

Lieberman AP, Pitha PM, Shin HS, Shin ML. Production of tumor necrosis factor and other cytokines by astrocytes stimulated with lipopolysaccharide or a neurotropic virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86(16):6348–52.

Minghetti L, Levi G. Microglia as effector cells in brain damage and repair: focus on prostanoids and nitric oxide. Prog Neurobiol. 1998;54(1):99–125.

Gonzalez-Scarano F, Baltuch G. Microglia as mediators of inflammatory and degenerative diseases. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1999;22:219–40.

Haslberger A, Romanin C, Koerber R. Membrane potential modulates release of tumor necrosis factor in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated mouse macrophages. Mol Biol Cell. 1992;3(4):451–60.

Noh H, Jeon J, Seo H. Systemic injection of LPS induces region-specific neuroinflammation and mitochondrial dysfunction in normal mouse brain. Neurochem Int. 2014;69:35–40.

Wang J, Li Y, Wang X, Chen W, Sun H, Wang J. Lipopolysaccharide induces amyloid formation of antimicrobial peptide HAL-2. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1838(11):2910–8.

Patil CS, Singh VP, Satyanarayan PS, Jain NK, Singh A, Kulkarni SK. Protective effect of flavonoids against aging- and lipopolysaccharide-induced cognitive impairment in mice. Pharmacology. 2003;69(2):59–67.

Ito D, Imai Y, Ohsawa K, Nakajima K, Fukuuchi Y, Kohsaka S. Microglia-specific localisation of a novel calcium binding protein, Iba1. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1998;57(1):1–9.

Brenner M. Role of GFAP in CNS injuries. Neurosci Lett. 2014;565:7–13.

Chen H, Chopp M, Schultz L, Bodzin G, Garcia JH. Sequential neuronal and astrocytic changes after transient middle cerebral artery occlusion in the rat. J Neurol Sci. 1993;188(2):109–16.

Kohama SG, Goss JR, Finch CE, McNeill TH. Increases of glial fibrillary acidic protein in the aging female mouse brain. Neurobiol Aging. 1995;16(1):59–67.

Eng LF, Ghirnikar RS. GFAP and astrogliosis. Brain Pathol. 1994;4(3):229–37.

Gieling RG, Wallace K, Han YP. Interleukin-1 participates in the progression from liver injury to fibrosis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;296(6):G1324–31.

Saperstein S, Chen L, Oakes D, Pryhuber G, Finkelstein J. IL-1beta augments TNF-alpha-mediated inflammatory responses from lung epithelial cells. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2009;29(5):273–84.

Watters O, O'Connor JJ. A role for tumor necrosis factor-α in ischemia and ischemic preconditioning. J Neuroinflammation. 2011;8:87.

Longhi L, Perego C, Ortolano F, Aresi S, Fumagalli S, Zanier ER, Stocchetti N, De Simoni MG. Tumor necrosis factor in traumatic brain injury: effects of genetic deletion of p55 or p75 receptor. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33(8):1182–9.

Huang WC, Lin YS, Wang CY, Tsai CC, Tseng HC, Chen CL, Lu PJ, Chen PS, Qian L, Hong JS, Lin CF. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 negatively regulates anti-inflammatory interleukin-10 for lipopolysaccharide-induced iNOS/NO biosynthesis and RANTES production in microglial cells. Immunology. 2009;128(1):e275–86.

Beurel E, Jope RS. Lipopolysaccharide-induced interleukin-6 production is controlled by glycogen synthase kinase-3 and STAT3 in the brain. J Neuroinflammation. 2009;6:9.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MEST)(NRF-2018R1D1A1B07044074).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J-BK, D-JP and M-AS performed experiment, organized and analyzed data. M-OK and P-OK designed the experiment, organized data, and wrote and correct the manuscript. P-OK managed general research and drafting. All authors read and approved this final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests to publish these results.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Kang, JB., Park, DJ., Shah, MA. et al. Lipopolysaccharide induces neuroglia activation and NF-κB activation in cerebral cortex of adult mice. Lab Anim Res 35, 19 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42826-019-0018-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42826-019-0018-9