Abstract

Background

Endoscopic third ventriculostomy (ETV) is becoming a popular option of treatment in carefully selected patients with hydrocephalus (Drake et al., Childs Nerv Syst 25:467-472, 2009). The success or possible outcome of its application in treating hydrocephalus can be predicted by employing a preoperative scoring system. An example of such a system is the endoscopic third ventriculostomy success score (ETVSS). It could form a basis for decision-making and prognostication. This study aimed to evaluate ETVSS as a preoperative predictive tool in children with hydrocephalus who satisfy the inclusion criteria for the option of ETV procedure as treatment modality.

Methodology

This is a prospective hospital-based study of 68 children under 2 years of age that presented at the Lagos University Teaching Hospital (LUTH) out of 161 children with hydrocephalus from November 2014 to April 2016. The predicted ETVSS was calculated by the addition of patients’ age, presumed aetiology and prior shunting. These children were stratified into three groups according to ETVSS as higher score predicts better ETV outcome and vice versa. They were followed up for 6 months to determine the success rate of ETV.

Results

The age of the study population ranged from 0 to 24 months with a mean age of 5.52 ± 5.48 months. 69.1% of these patients were male and 30.9% were female with a male to female ratio of 2.2:1. The mean predicted ETVSS (48.82 ± 19.20%) and actual ETV success score (56.20 ± 15.10%) using the ANOVA were significantly related (p value < 0.05).

Conclusion

This study concluded that the early outcome of ETV in children below 2 years of age with hydrocephalus is directly related to the preoperative ETVSS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The increasing popularity of endoscopic third ventriculostomy (ETV) in the treatment of hydrocephalus over the last decades has improved the outcome of treatment, with the pertinent question presently centred on selection criteria that predict good outcome [1, 2]. Hydrocephalus is a devastating surgical disease which, when left untreated, causes impaired psychosocial and mental development and cosmetically disfiguring craniofacial disproportion and could ultimately lead to death. Early appropriate treatment is associated with a significant reduction in morbidity and mortality as well as improvement in the quality of life of children presenting with hydrocephalus [2, 3]. The treatment of hydrocephalus has evolved over time. Shunting has been the traditional approach in treating the condition with the attendant complications such as shunt infection and malfunction [3]. In the last two decades, there is an upsurge in the use of ETV in the treatment of hydrocephalus in selected patients with a reduction of complications that traditionally accompanying shunting [1, 3]. The endoscopic third ventriculostomy success score (ETVSS) has been validated to be a useful preoperative tool that predicts the outcome of ETV [4,5,6,7]. Despite the major advantage of being shunt free, ETV is associated with varying success rates ranging from 50 to 90% [5] and could lead to progression of hydrocephalus that would necessitate another cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) diversion. It is therefore appropriate to devise clear-cut selection criteria among children with hydrocephalus in order to derive maximal benefit from the procedure in view of the moderate failure rate of the procedure.

The development of ETVSS is an attempt to accurately predict the outcome of ETV and quantify the common prognostic factors such as patient’s age, aetiology of hydrocephalus and history of previous shunting [8]. The scoring system helps to identify independent variables that predict a good outcome. This study was specifically aimed at evaluating the role of ETVSS as a preoperative parameter in children with hydrocephalus at Lagos University Teaching Hospital (LUTH), Lagos, Nigeria.

Methodology

This was a prospective hospital-based cohort study of 68 eligible children who met the inclusion criteria and underwent ETV out of a total of 161 patients who presented with hydrocephalus at the LUTH, Lagos, Nigeria, during an 18-month study period from November 2015 to April 2016 after obtaining ethics clearance from the human and research ethics committee. The inclusion criteria involve children under 2 years who presented with clinical features and brain computed tomography scan findings of hydrocephalus and qualified for an ETV procedure by the exclusion criteria.

The exclusion criteria were children above two years with hydrocephalus and unconscious, comatose and brain-dead patients with hydrocephalus. Patients who were treated for hydrocephalus with techniques other than ETV and children with hydrocephalus without brain computed tomography (CT) scan were also excluded. Patients who had choroid plexus cauterization (CPC) in addition to ETV were excluded.

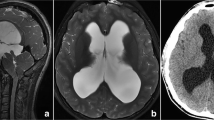

All parents and guardians of children who satisfied the inclusion criteria were given an informed consent form to fill and sign. Gestational age at birth, presumed aetiology of hydrocephalus, previous history of shunting and age at surgery were recorded. The presumed aetiology of hydrocephalus was confirmed by brain computed tomography (CT) scan as part of preoperative evaluation. Occipitofrontal circumference (OFC) was measured at presentation using the glabella and occiput as reference points. Developmental milestones (social smile, neck control, sitting with and without support, crawling, standing, walking and talking) were evaluated and documented.

Endoscopic set-up was arranged. The right lateral ventricle was cannulated, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) flow was confirmed and a flexible endoscope was introduced into the frontal horn of the right lateral ventricle through Kocher’s point which gives a direct trajectory through the foramen of Monro to the floor of the third ventricle. The floor of the third ventricle was identified using known landmarks (the mammillary bodies, infundibular recess and clivus) with basilar artery complex lying at the posterior edge of the third ventricular floor at the level of the mammillary bodies. The third ventricular floor was fenestrated bluntly using electrocautery, and at the ventriculostomy opening, cerebrospinal fluid flow was seen.

The ETVSS was calculated from the addition of scores for age, presumed aetiology (from brain CT scan) and presence or absence of previous shunt insertion, and the calculated (predicted) ETVSS was documented for each patient.

Table 1 shows the ETVSS chart. ETVSS is calculated by addition of the scores of age of patient at surgery, presumed aetiology and whether or not there has been previous shunting.

Data collection and analysis

Data collected include birth history, presumed aetiology of hydrocephalus, presence or absence of previous shunting, complications at presentation, developmental milestones, brain CT scan findings, treatment and outcome. Patient’s confidentiality was protected by assigning a serial number to each patient at entry. The data collected was analysed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 22 (Illinois, USA).

Correlation was done to establish relationships between ETVSS and ETV outcome using Pearson’s correlation ranking order, while the analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Kaplan-Meier statistical tool were used for comparing means where applicable, and p value < 0.05 was taken as significant. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was used to determine the predictive strength of the variable. Follow-up was for a period of 6 months which was carried out via routine clinic visits and mobile phone chat, and OFC and developmental milestone assessed.

Results

Sixty-eight eligible patients with complete data were analysed. The age of the 68 patients ranged from 0 to 24 months with a mean of 5.45 ± 5.41 months. Fifty-seven percent of patients were less than 6 months old while another 20% were between 6 and 12 months old. Forty-seven (69.1%) patients were male, while 21 (30.9%) were female with a male to female ratio of 2.2:1. Fifty-three (77.9%) of the 68 patients with hydrocephalus had no previous shunting prior to the ETV procedure, while 15 (22.1%) had ventriculoperitoneal shunting prior to ETV.

At 6 months follow-up, the ETV was successful in children aged 6 to < 12 months (100%, p = 0.001), followed by those aged 12 to 24 months (80%, p = 0.05) and 1 to < 6 months (69.2%), while ETV failed in 80% of patients aged less than 1 month.

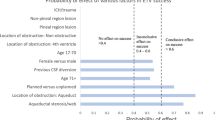

It shows a significant area under the curve above the reference level of 0.5. The area under the curve (AUC) was 0.871, and the sensitivity and specificity of predicted ETVSS were 84% and 88.9%, respectively.

Eighteen (26.5%) of the 68 patients had failed ETV which was the major complication, but other minor complications were seen in 3 patients with surgical site infection that was treated daily with wound care and antibiotics.

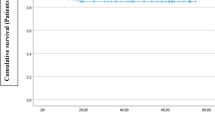

The survival period is defined as the measured period of success of ETV within which there is no indication for an alternative secondary surgical intervention, and Fig. 2 shows that the higher the predicted ETVSS, the higher is the survival period of ETV and vice versa.

Discussion

The decision to treat a child with hydrocephalus surgically can be tasking in view of the options available for the treatment of hydrocephalus. The decision is based on available treatment options, efficacy of such options, available expertise, equipment and choice of treatment by the patient’s family.

ETV is a treatment option that seems to have fewer complications compared with the more traditional method of shunting [1, 3, 9, 10]. However, the use of a well-tailored selection criteria like the ETVSS done preoperatively is essential to determine who will likely benefit from ETV and help reduce the need for repeat procedures following failures [8, 9, 11].

ETV success is defined as freedom from the subsequent surgical procedure for the purpose of cerebrospinal fluid diversion [6]. A failed ETV is defined as having occurred in cases that will require subsequent surgical intervention by CSF diversion after primary treatment with ETV or death within 6 months after first ETV [6].

Fani et al. [11] in their study involving 59 patients below 2 years of age showed findings similar to this study as regards age and sex distribution. Males accounted for 62.7% of their patients, and 55.95% of all patients were below 6 months compared to 64.48% in this study who were less than 6 months old. In our study population, the trend to improve outcome increases to 12 months, and thereafter, there was a slight drop in the percentage of successful procedure.

In comparing our study to that of Breimer et al. [12] who externally validated ETVSS in 104 paediatric patients, age stratification was slightly different as 43.3% of the 104 patients studied were between 1 and less than 10 years probably due to a higher age of study population in their study. This study revealed that majority of the patients—61.8%—had presumed aqueductal stenosis (Table 2). The aetiological distribution showed a similar pattern of distribution from some literature. Breimer et al. [12] showed that the majority had aqueductal stenosis which accounted for 26.9%. The higher number of study population when compared to this study may have accounted for a lesser percentage of patients with aqueductal stenosis. However, Fani et al. [11] with almost similar study population showed that aqueductal stenosis was the commonest cause in the age group less than 2 years of age. As expected, this study showed that the measured mean survival period (time of success without intervention) for each stratum of the predicted ETVSS increases as the grading increases.

The findings from this study were similar to those by Fani et al. [11] and Breimer et al. [12] which showed that the success rate of ETV has a linear association with the predicted ETVSS score. This similarity in the predictive value of ETVSS may be a result of similar demography and duration of follow-up following ETV.

Kulkarni et al. [13] in a multicenter cohort study showed that the mean predicted ETVSS was 57.9% with a closely related actual ETV success rate of 59.2%. Kulkarni et al. [13] validated the ETVSS model and showed that the area under the curve (AUC) was 0.68. Naftel et al. [14] validated ETVSS with a follow-up period of 6 months, and the AUC was 0.74. In comparison to the above studies, this study showed a slight difference as the AUC was 0.871 with a sensitivity of 84% and specificity of 88.9% (Fig. 1). The difference may be due to the difference in sample sizes and probably late presentation in patients with hydrocephalus in our environment (Table 3). However, the AUCs in these studies and ours showed a significant predictive strength of ETVSS. The mean predicted ETVSS from this study was 48.82 ± 19.20% with a mean success score of 56.20 ± 15.10% (Table 4). This finding is similar to that of Kulkarni et al. [15] who showed that the mean predicted ETVSS was 57.9% with the closely related actual ETV success rate of 59.2%.

The correlation coefficient between predicted ETVSS and ETV outcome was 0.65 with a significant p value less than 0.05. This is similar to the findings observed by Kulkani et al. [15] that showed a linear correlation between predicted ETVSS and actual success of ETV.

The mean survival period after ETV therefore increases with increase in ETVSS using the Kaplan-Meier statistic tool as shown in Fig. 2 compared to findings from the work of Kulkarni et al. [13]. A positive correlation coefficient of 0.65 was recorded between the predicted ETVSS and actual ETV outcome within the follow-up period of 6 months using Pearson’s correlation ranking order.

Conclusion

From this study, preoperative ETVSS which predicts ETV outcome is a valuable tool in deciding which children with hydrocephalus will most likely benefit from ETV, since findings from this study revealed that predicted ETVSS closely mirrors and predicts actual ETV outcome up to 6 months of follow-up.

We recommend the following:

ETVSS should be used preoperatively to evaluate the likely outcome of ETV in children with hydrocephalus.

ETVSS should form the basis for making a decision as to which children with hydrocephalus will benefit from the ETV procedure.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- CSF:

-

Cerebral spinal fluid

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- ETV:

-

Endoscopic third ventriculostomy

- ETVSS:

-

Endoscopic third ventriculostomy success score

- OFC:

-

Occipitofrontal circumference

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

References

Drake JM, Kulkarni AV, Kestle J. Endoscopic third ventriculostomy versus ventriculoperitoneal shunt in paediatric patients: a decision analysis. Childs Nerv Syst. 2009;25(1):467–72.

Bankole OB, Ojo OA, Nnadi NM, Kanu OO, Olatosi JO. Early outcome of endoscopic third ventriculostomy and choroid plexus cauterization in childhood hydrocephalus. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2015;15:524–8.

Rekate HL. The definition and classification of hydrocephalus: a personal recommendation to stimulate debate. Cerebrospinal Fluid Res. 2008;5:2.

Warf BC. Hydrocephalus in Uganda: the predominance of infectious origin and primary management with endoscopic third ventriculostomy. J Neurosurg. 2005;102(1):1–15.

Dandy WE. Extirpation of the choroid plexus of the lateral ventricle in communicating hydrocephalus. Ann Surg. 1918;68:569–79.

Mwenshi MM, Amosun SL, Ngoma MS, Nkandu EM, Sichizya K, Chikoya L, et al. Endoscopic third ventriculostomy and choroids plexus cauterization in childhood hydrocephalus in Zambia. Med J Zambia. 2010;37(4):246–52.

Rahman A, Rahman MZ, Islam M, Sultan M. Endoscopic third ventriculostomy- experience of 16 cases. JCMCTA. 2008;19(2):27–32.

Warf BC, Mugamba J, Kulkarni AV. Endoscopic third ventriculostomy in the treatment of childhood hydrocephalus in Uganda: report of a scoring system that predicts success. J Neurosurg Pediatrics. 2010;5(1):143–8.

Kulkarni AV, Drake JM, Kestle JR, Mallucci CL. Predicting who will benefit from endoscopic third ventriculostomy compared with shunt insertion in childhood hydrocephalus using ETV success score. J Neurosurg Pediatric. 2010;6:310–5.

Pople IK. Hydrocephalus. Surgery (oxford). 2004;22(3):60–3.

Fani L, de Jong TH, Dammers R, van Veelen. Endoscopic third ventriculocisternostomy in hydrocephalic children under 2 years of age: appropriate or not? A single-center retrospective cohort study. Childs Nerv Syst. 2003;29:419–23.

Breimer GE, Sival DA, Brusse-Keizer MGJ, Hoving EW. An external validation of the ETVSS for both short-term and long-term predictive adequacy in 104 pediatric patients. Childs Nerv Syst. 2013;29:1305–11.

Kulkarni AV, Drake JM, Mallucci CL, Sgouros S, Roth J, Constantini S. Endoscopic third ventriculostomy in the treatment of childhood hydrocephalus. J Pediatr. 2009;155:254–9.

Naftel RP, Reed GT, Kulkarni AV, Wellons JC. Evaluating the children’s hospital of Alabama endoscopic third ventriculostomy experience using ETV success score: an external validation study. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2011;8(5):495–501.

Kulkarni AV, Riva-Cambrin J, Browd SR. Use of the ETV success score to explain the variation in reported endoscopic third ventriculostomy success rates among published case series of childhood hydrocephalus. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2011;7:143–6.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was provided by any funding body.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EM is the chief coordinator and helped in the drafting and design of this manuscript. OB and MB contributed to the methodology and literature review. OK and OO contributed to the results and literature review. EP and JE contributed to the data collection, analysis and discussion. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This paper has been submitted with full responsibility, following the due ethical procedure of the Lagos University Teaching Hospital Human Research and Ethics committee, which was approved on 23 April 2014 (ADM/DCST/HREC/1757). There is no duplicate publication, fraud, plagiarism, or concern about animal or human experimentation.

Consent to participate in the study was obtained from the parent or legal guardians of the participants at clinic appointment after consultation, as they were all under 18 at the time of the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Morgan, E., Bankole, O.B., Mofikoya, B.O. et al. Endoscopic third ventriculostomy success score in predicting short-term outcome in 68 children with hydrocephalus in a resource-limited tertiary centre in sub-Saharan Africa. Egypt J Neurosurg 34, 31 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41984-019-0057-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41984-019-0057-4