Abstract

Background

Breast cancer-related lymphedema often causes cellulitis and is one of the most common complications after breast cancer surgery. Streptococci are the major pathogens underlying such cellulitis. Among the streptococci, the importance of the Lancefield groups C and G is underappreciated; most cases involve Streptococcus dysgalactiae subspecies equisimilis. Despite having a relatively weak toxicity compared with group A streptococci, Streptococcus dysgalactiae subspecies equisimilis is associated with a mortality rate that is as high as that of group A streptococci in cases of invasive infection because Streptococcus dysgalactiae subspecies equisimilis mainly affects elderly individuals who already have various comorbidities.

Case presentation

An 83-year-old Japanese woman with breast cancer-related lymphedema in her left upper limb was referred to our hospital with high fever and acute pain with erythema in her left arm. She showed septic shock with disseminated intravascular coagulation. Blood culture showed positive results for Streptococcus dysgalactiae subspecies equisimilis, confirming a diagnosis of streptococcal toxic-shock syndrome. She survived after successful intensive care.

Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, this case represents the first report of Streptococcus dysgalactiae subspecies equisimilis-induced streptococcal toxic-shock syndrome in a patient with breast cancer-related lymphedema. Breast cancer-related lymphedema is a common problem, and we must pay attention to invasive streptococcal soft tissue infections, particularly in elderly patients with chronic disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Breast cancer is one of the most common cancers in women. While survival after breast cancer has significantly improved with the advent of multimodal therapy [1], aggressive treatment sometimes induces complications. In particular, breast cancer-related lymphedema (BCRL) is one of the most common problems, often resulting in the development of cellulitis. Most such cases of cellulitis are caused by streptococci or staphylococci, which are normal bacterial flora of the skin. To date, the streptococcal pathogens causing skin and soft tissue infections have mainly been identified as group A streptococci (GAS), mostly isolated as Streptococcus pyogenes. However, other types of β-hemolytic streptococci become more important with ageing. Streptococcus dysgalactiae subspecies equisimilis (SDSE), classified as a group C or G Streptococcus, sometimes shows similar clinical manifestations to GAS, but with weaker toxicity. Increased survival of adults with underlying chronic conditions may be a factor contributing to the increasing incidence of SDSE infections [2].

Case presentation

Our patient was an 83-year-old Japanese woman who had undergone left mastectomy for breast cancer 18 months earlier. The pathological diagnosis according to the Union for International Cancer Control 7th TNM classification for breast cancer was T2 N2 M0. The receptor expression was positive for estrogen and progesterone receptors but negative for human epidermal growth receptor 2. She received adjuvant chemotherapy consisting of four cycles of doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide (AC) and radiotherapy to her axillary and supraclavicular regions. After these therapies, she had been prescribed letrozole. No other relevant past history was found, including no history of diabetes, heart disease, or use of trastuzumab as pharmacotherapy, potentially causing cardiac toxicity. The dose of doxorubicin was lower than cardiac toxicity doses, and there were no abnormalities in organ function. Six months after mastectomy, BCRL of her left upper limb appeared and gradually worsened.

She presented to our hospital the day after a high fever and severe pain in her left arm with erythema. She initially reported only slight pain in her left arm, but serious aggravation developed within 24 hours, along with a rash and high fever. She presented with: blood pressure, 90/40 mmHg; heart rate, 120 beats/minute; axillary body temperature, 39.6 °C; respiratory rate, 24 breaths/minute; and peripheral oxygen saturation, 96%. She was in a confused state, and a physical examination revealed swelling of her left upper limb and a generalized erythematous macular rash (Fig. 1a). Laboratory data indicated a high inflammatory state with extreme leukopenia and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC): white blood cell count (WBC), 900/μL; platelets (PLT), 7.8×104/μL; international normalized ratio, 1.7; activated partial thromboplastin time, 48.5 seconds; C-reactive protein, 1.3 mg/dL; fibrocyte-derived protein (FDP), 53.7 μg/mL; and procalcitonin, 8.37 ng/mL (Table 1). Computed tomography (CT) of her left arm showed thickening of the superficial fascial layer (Fig. 1b). There were no remarkable changes in chest X-rays. Severe soft tissue infection of her left upper limb with septic shock and DIC was diagnosed. As a result, imipenem/cilastatin (IMP/CS) at 3.0 g/day, intravenously administered immunoglobulin (IVIG) at 5.0 g/day, thrombomodulin at 12,800 U/day, noradrenaline at 0.1 μg/kg per minute, and 30% oxygen were immediately administered. Her hemodynamic status stabilized with the administration of noradrenaline, and her mean arterial pressure value was greater than 65 mmHg, which is recommended by the Surviving Sepsis Campaign.

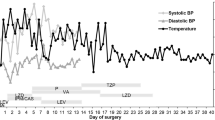

Two days after starting this therapy, her C-reactive protein was still elevated at 23.8 mg/dL, and positive results for Gram-positive cocci, probably Streptococcus, were obtained from the first cultures. Aerobic and anaerobic blood cultures were taken at each assessment. Culture of the cellulitis was not taken. Antibiotics were changed to penicillin G (PCG) at 16,000 U and clindamycin (CLDM) at 1800 mg/day. Group G SDSE was later identified using the Lancefield grouping and an automated bacterial identification system (VITEK® 2; bioMerieux, USA), which showed category agreement from 96 to 100% for Streptococcus agalactiae and from 91 to 100% for Streptococcus pneumoniae in antimicrobial susceptibility testing [3]. The isolated SDSE was highly sensitive to PCG and CLDM. The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were under 0.06 μg/ml for PCG and under 0.12 μg/ml for CLDM. Administration of IVIG and thrombomodulin were continued until day 3. Four days after starting treatment, PLT counts indicated a tendency toward improvement, and noradrenaline was completely withdrawn (Fig. 2). Her left arm was still edematous, but the severe pain had resolved. She was discharged from our intensive care unit (ICU) on day 4. Two sets of blood cultures, which were collected 7 days after starting the treatment, were both negative, and intravenous administration of antibiotics (IMP/CS, PCG with CLDM) was continued until 18 days after starting the therapy. During the following 2 weeks, oral administration of 900 mg per day of CLDM was prescribed.

White blood cell counts, platelet counts, C-reactive protein concentration in the peripheral blood, and medication administration. CLDM clindamycin, CRP C-reactive protein, ICU intensive care unit, IPM/CS imipenem/cilastatin, IVIG intravenously administered immunoglobulin, NA noradrenaline, PCG penicillin G, PLT platelet, TM thrombomodulin, WBC white blood cell

She came to our out-patient clinic every 3 months for 2 years. There was no recurrence of breast cancer or cellulitis within 2 years of the onset of streptococcal toxic-shock syndrome (STSS).

Discussion

Breast cancer is one of the most common cancers in women, with an incidence rate of 89.7 per 100,000 women in Western Europe. High survival rates have been achieved in these countries [1], but these high survival rates can be accompanied by other problems. BCRL is one of the most common complications after breast cancer treatment. The overall incidence of BCRL has been reported as 26% after mastectomy, and axillary lymph node dissection with axillary radiotherapy significantly increases the risk of BCRL (relative risk, 6.9) [4, 5]. As lymphedema provides an ideal environment for bacterial growth, probably because of the decreased lymphatic flow and impaired elimination of phagocytosed bacteria, soft tissue infection is quite common as a complication among patients with BCRL [6]. Most of the causative pathogens are Staphylococci or Streptococci, and infection is often treated without serious progression. However, streptococcal infections occasionally develop into STSS. The development of STSS significantly increases the risk of mortality, which may exceed 50% [7]. Criteria for the diagnosis of STSS were established by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 2010 (Table 2) [8]. Most cases of STSS are caused by GAS, but cases caused by SDSE belonging to Lancefield serogroup C or G have recently been reported. In 2011, a Japanese surveillance study reported the involvement of GAS in 78% of STSS (76 cases), group G streptococci in 21% (22 cases, all involving SDSE), and group C streptococci in less than 2% (two cases, one with SDSE, and the other with Streptococcus constellatus subspecies pharyngis) [9]. Although GAS can affect even the healthy, SDSE mainly affects elderly individuals with chronic diseases, such as diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, malignancy, and immunosuppression. In particular, breakdown of the skin was noted in 30 to 60% of cases [2], while the most common clinical manifestation of invasive SDSE infection is cellulitis (41%) [2]. The mortality rate from SDSE bacteremia is 15 to 18%, which is comparable to that for GAS bacteremia. SDSE infection by itself is considered less severe than GAS bacteremia, but the effects of patient characteristics, such as age and underlying diseases, may increase the infection severity [2].

In our case, the patient had undergone left mastectomy and axial lymph node dissection with additional chemotherapy and radiotherapy following hormone therapy. Under such aggressive treatment, no sign of recurrence was seen for more than 2 years postoperatively, despite advanced lymph node metastasis. However, mastectomy with axial dissection and radiotherapy induced BCRL. This elderly woman with BCRL was at high risk of invasive SDSE infection and eventually developed STSS induced by SDSE. The clinical course, which progressed rapidly (within 24 hours) and emerged in the soft tissue, was typical of STSS [7]. The route of transmission of the pathogen into the deep soft tissue was uncertain, but the edematous subcutaneous tissue might have provided a suitable environment for exponential bacterial growth. She presented signs of septic shock, requiring noradrenaline for 4 days in our ICU. In addition, her confused mental state, soft tissue infection following DIC with high inflammatory status (CRP 23.8 mg/dL; procalcitonin 8.37 ng/mL) and extreme leukopenia (900/μL) all suggested severe infection and toxicity. Thrombocytopenia with elevation of FDP also remained until day 4, despite appropriate DIC therapy (Fig. 2). Lastly, SDSE was isolated from the blood, and STSS was confirmed based on the CDC criteria (Table 2), with DIC, soft tissue infection, and generalized erythematous macular rash. SDSE is not as toxic as GAS, and no vital organ dysfunction developed, such as respiratory failure, liver involvement, or renal impairment. These factors were considered the main reasons why our patient survived her case of STSS. This report highlights the risk of life-threatening infection developing among survivors of malignancy. Therefore, invasive streptococcal infection should be taken into account as a risk factor after breast cancer treatment. Ageing and advances in medicine have created the need to address such cases.

Conclusion

We have reported a case of SDSE-induced STSS with BCRL. Infectious diseases can become a life-threatening problem after successful treatment for malignant disease.

Abbreviations

- BCRL:

-

Breast cancer-related lymphedema

- CDC:

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CLDM:

-

Clindamycin

- DIC:

-

Disseminated intravascular coagulation

- FDP:

-

Fibrocyte-derived protein

- GAS:

-

Group A streptococci

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- IMP/CS:

-

Imipenem/cilastatin

- IVIG:

-

Intravenously administered immunoglobulin

- PCG:

-

Penicillin G

- PLT:

-

Platelets

- SDSE:

-

Streptococcus dysgalactiae subspecies equisimilis

- STSS:

-

Streptococcal toxic-shock syndrome

References

World Health Organization. Breast cancer: prevention and control 2015. http://www.who.int/cancer/detection/breastcancer/en/. Accessed 19 June 2017.

Rantala S. Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis bacteremia: an emerging infection. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;33(8):1303–10.

Ligozzi M. Evaluation of the VITEK 2 System for Identification and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing of Medically Relevant Gram-Positive Cocci. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40(5):1681–6.

Erickson VS, Pearson ML, Ganz PA. Arm edema in breast cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93(2):96–111.

Ryttov N, Holm NV, Qvist N, Blichert-Toft M. Influence of adjuvant irradiation on the development of late arm lymphedema and impaired shoulder mobility after mastectomy for carcinoma of the breast. Acta Oncologica. 1988;27(6a):667–70.

Simon MS, Cody RL. Cellulitis after axillary lymph node dissection for carcinoma of the breast. Am J Med. 1992;93(5):543–8.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Predictors of Death after Severe Streptococcus pyogenes infection. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/15/8/09-0264_article. Accessed 19 June 2017.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Streptococcal toxic-shock syndrome Case Definition 2010. http://wwwn.cdc.gov/nndss/conditions/streptococcal-toxic-shock-syndrome/case-definition/2010/. Accessed 19 June 2017

National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Japan. Infectious Agents Surveillance Report. IASR 33: 209-210, August 2012. Streptococcal infections in Japan, April 2006-2011. http://www.nih.go.jp/niid/en/iasr-vol33-e/865-iasr/2505-tpc390.html. Accessed 19 June 2017.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Dr Yuto Fukui in the Department of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, Faculty of Medicine, Toho University for advice on the diagnosis and interventions for STSS. No funding was received by any of the authors.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Availability of data and materials

Please contact the authors for data requests.

Authors’ contributions

MS developed the concept of the report and wrote the manuscript. FS and HO refined the concept and co-wrote the manuscript. MY, YK, and SM also co-wrote and developed the manuscript. HK reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and the accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Sumazaki, M., Saito, F., Ogata, H. et al. Streptococcal toxic-shock syndrome due to Streptococcus dysgalactiae subspecies equisimilis in breast cancer-related lymphedema: a case report. J Med Case Reports 11, 191 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-017-1350-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-017-1350-z