Abstract

Background

Several studies have linked vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGFs) with metabolic syndrome or its components. However, there has been no systematic appraisal of the findings of these studies to date. The current systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted to explore this association.

Methods

PubMed, EMBASE, the Cochrane library, and clinical trials registries were used to retrieve peer-reviewed clinical studies that had evaluated the association of VEGFs with metabolic syndrome or its components without applying language and date restrictions. The final search was performed on 29 September 2017.

Results

We included 32 studies in this systematic review and meta-analysis, of which 16 studies (19 study arms) were included in the meta-analysis and remaining studies were qualitatively assessed. Overall, VEGF-A, VEGF-B and VEGF-C were strongly associated with metabolic syndrome or its components. The components of metabolic syndrome varied in their association. Obesity was not correlated with increased VEGF-A expression (p = 0.12), whereas VEGF-B and VEGF-C expression was significantly higher in those with obesity. In contrast, hyperglycemia in type 1 diabetes was strongly associated with increased VEGF-A levels (p < 0.00001), as was type 2 diabetes (p = 0.0006). The studies included in the qualitative analysis similarly showed an increase in VEGF family expression in people with metabolic syndrome, and with its components.

Conclusion

The increased concentrations of vascular endothelial growth factors are variably associated with metabolic syndrome or its components. Each VEGF protein has a unique set of associations with the disease state.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) definition, the metabolic syndrome (MetS) comprises insulin resistance (IR) (defined as impaired fasting glucose, impaired glucose tolerance or type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM)), associated with at least two of the following: obesity (waist-to-hip ratio > 0.90 in men or > 0.85 in women, or BMI > 30 kg/m2), dyslipidemia (TGs ≥ 150 mg/dL and/or HDL-C < 35 mg/dL in men or < 39 mg/dL in women) and hypertension (BP ≥ 140/90 mmHg) [1]. The MetS directly increases the risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality, and in the current obesity era, it demands novel therapeutic strategies to protect and treat the affected population [1]. A perturbed crosstalk between adipocytes and endothelial cells (ECs) has been found to play a key role in the pathogenesis of obesity and consequent metabolic disturbances [2, 3]. Communication between adipocytes and ECs mostly takes place through the vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGFs) and their receptors (VEGFR1, VEGFR2, and VEGFR3), thus the role of these factors in metabolic disturbances has been the focus of scientific attention in recent years [3, 4]. Clarifying the association between VEGFs and parameters of the metabolic syndrome holds both therapeutic and preventive potential, and as such, requires a systematic analysis of the existing data.

Clinical research on four VEGF proteins (VEGF-A, VEGF-B, VEGF-C, and VEGF-D) in the context of the metabolic syndrome have yielded diverse results. VEGF-A-induced angiogenesis has been found to diminish metabolic complications caused by a high-fat diet and the metabolic syndrome. Accordingly, there is evidence that increased circulating and adipose tissue levels of VEGF-A in obesity significantly decrease in patients with a dramatic weight loss [5,6,7]. The metabolic role of VEGF-B, on the other hand, seems to be more complex than that of VEGF-A [8]. While some authors report increased circulating and adipose tissue VEGF-B levels [9] in obese individuals, others disagree [10]. A further study in mice implicates increased VEGF-B expression in reducing metabolic complications [11]. The metabolic roles of VEGF-C, VEGF-D, and a VEGF discovered in human placenta called placental growth factor (PIGF) have not been studied as extensively as those of VEGF-A and VEGF-B, but the evidence suggests that circulating VEGF-C is significantly increased in obese as compared to lean individuals, whereas both circulating and adipose tissue levels of VEGF-D seem to be significantly lower in obese patients as compared to lean individuals, showing a positive correlation with the degree of insulin resistance [9, 10]. Furthermore, blockade of VEGF-C and VEGF-D in mice reduces adipose tissue inflammation and improves insulin sensitivity [12].

The ability of the VEGF superfamily to increase perfusion and therefore improve insulin delivery in adipose tissues could be crucial for the treatment of insulin resistance. Furthermore, these proteins may play a role in preventing lipotoxicity and improving insulin signaling through the regulation of FA uptake. It is therefore important to explore the expression of these proteins in such patients [8]. Since there has been no systematic appraisal of the findings regarding the metabolic role of VEGFs to date, we aimed to systematically review and quantify all the available data on the expression of VEGF-A, VEGF-B, VEGF-C, VEGF-D and PIFG in adults, adolescents and children with metabolic syndrome or its components.

Methods

The systematic review and meta-analysis was carried out in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines [13], and the review was registered in the PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (CRD42017077685).

Review question (PICOTS)

The question for our study was: In children, adolescents and adults, are people with metabolic syndrome, or the components of metabolic syndrome, compared with controls, associated with higher concentrations of VEGF family members in cross-sectional or cohort studies?

Data sources and search strategies

A comprehensive systematic search was carried out using PubMed, the Cochrane Library, EMBASE and international clinical trials registries without time or language restrictions. The final search was conducted on 29 September 2017. The search strategy as used for PubMed was; (“vascular endothelial growth factor” OR “VEGF-A” OR “VEGF-B” OR “VEGF-C” OR “VEGF-D” OR “PIGF”) AND (“metabolic syndrome” OR “diabetes” OR “T2DM” OR “obesity” OR “overweight” OR “hypertension” OR “hyperglycemia” OR “high blood sugar” OR “hypertriglyceridemia” OR “low-density lipoprotein” OR low-HDL” OR “high-density lipoprotein” OR “insulin resistance” OR “insulin resistance syndrome”) AND (“fasting blood glucose” OR “FBG” OR “fasting blood insulin” OR “FBI” OR HOMA-IR” OR “postprandial insulin” OR “postprandial glucose” OR “body mass index” OR “BMI” OR “body fat composition” OR “fasting metabolic rate” OR “HbA1c” OR “glycated haemoglobin” OR “body weight”).

The search was modified for used in EMBASE, the Cochrane Library and the clinical trials registries.

Inclusion criteria

Citations were included if they met the following criteria: the study was in children, adolescents, and or adults; the participants in at least one cohort had metabolic syndrome or at least one component of the metabolic syndrome; the expression of VEGF-A or a member of the VEGF superfamily was reported, and a comparison was drawn between the individuals with or without metabolic syndrome or its components. The studies were excluded if they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Articles without full text, conference abstracts, comments, reviews, and studies based on animal models or cell lines were excluded.

Study selection and quality assessment

The citations and full-text articles were assessed for inclusion or exclusion independently by two authors using the double-blind coding assignment methodology within EPPI-Reviewer 4 [14]. The quality of the studies was determined using the National Institute of Health Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies [15]. Two authors assessed and rated the quality of the included studies. Any disagreements regarding the article selection or quality assessment were resolved by consensus, or by reference to a third party.

Data extraction

The data extraction was performed by two authors independently. Each author was assigned half of the total included studies, and two authors individually checked the extracted data. The data included: study characteristics (disease state, country, study type, population, age, gender, and funding source), VEGF family member measured, and VEGF expression levels. If the data were only available in figures, the data were extracted using WebPlotDigitizer [16]. Standard errors were converted to standard deviations using the equation: \(SD = SEM \times \sqrt N\), where N is the number in the study arm.

Statistical analysis

Extracted data were analyzed using Review Manager 5.3 [17]. As the data were reported in different formats, we calculated standardized mean differences (SMD) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). To convert SMDs to mean differences (MD), we multiplied the SMD by the median standard deviation of studies reporting the outcome of choice using the same format. To avoid double-counting, the population size of study arms that were used twice were divided by two.

The meta-analysis was done using a random-effects, inverse variance model, as the differences in effect sizes were expected to be modified by variations in populations. Heterogeneity was reported as τ2, χ2, and I2. A funnel plot was created to identify potential publication bias in the included studies. All statistical results were considered to be significant if the p-value was < 0.05.

The potential for publication bias was tested by measuring asymmetry in the funnel plot as determined by Egger et al. [18] using the regtest.rma function in the metaphor package (Version 2.0-0) [19].

A priori subgroup analysis/sensitivity analysis

We planned a priori subgroup analyses based on: concomitant medication, funding source, age of participants, co-morbidities of participants and gender of participants.

Results

Study characteristics

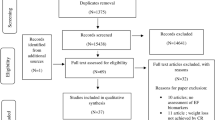

In total, 1345 citations were uploaded into EPPI-Reviewer 4 [14] (Fig. 1). After removal of duplicates, 729 abstracts were subjected to inclusion as stated above. After coding at the title/abstract level, 79 full texts were obtained. Of these, 32 studies including 36 study arms were included in the final analysis (Table 1) [9, 20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50]. Of these, 19 study arms from 16 studies were included in the meta-analysis.

Quality of included studies

The quality of the included studies is presented in Table 2. Of the 32 included studies, 18 studies were rated as “poor”, 12 were rated “fair” and only two study was rated as “good” quality. Most of these studies were cross sectional, thus unable to establish temporality between exposure and outcome. This significantly limits the potential for any causal inference. In addition, most studies did not adjust for confounding variables in statistical analyses. This likely introduced bias into the reported associations. The sample sizes for many of these studies were small and lacked evidence of power calculations. Even when sample sizes were adequate, control participants were often drawn from populations sufficiently different from cases (e.g. hospital staff compared to patients) that any results from comparisons may be biased.

Association of VEGFs with metabolic syndrome or its components—meta-analysis

We undertook a subgroup meta-analysis of VEGFs expression in people with and without metabolic syndrome or its components by VEGF protein (Fig. 2). Most studies measured VEGF-A concentrations, with only two studies each reporting on VEGF-B, VEGF-C or VEGF-D. In all cases except VEGF-D, the expression of the VEGF family was higher in people with metabolic syndrome or components of the metabolic syndrome. Expression of VEGF-A was significantly higher (SMD = 0.52; 95% CI 0.34, 0.71; p < 0.0001) in people with metabolic syndrome or components thereof. This equates to an increase in VEGFs expression of over 50 pg/mL. The two studies (three study arms) reporting on VEGF-B expression, as well as the two studies (three study arms) reporting on VEGF-C, were associated with significantly higher VEGF expression (p < 0.0001, p < 0.0001, respectively). Heterogeneity as measured by I2 varied from 0% (VEGF-C) to 91% (VEGF-D). The latter was driven entirely by Gomez-Ambrosi [9].

To investigate differences in VEGFs expression based on different metabolic syndrome components, we undertook a meta-analysis of studies of people with at least three of the five components of the metabolic syndrome, or where the study authors stated that the cohort had metabolic syndrome (Fig. 3). Only two studies could be included in the meta-analysis. However, these two studies both demonstrated a significant increase in VEGF-A expression, and together were statistically significant (SMD = 1.27; 95% CI 0.09, 2.45; p = 0.03). This equates to a mean difference in VEGF-A expression of approximately 150 pg/ml. Heterogeneity as measured by I2 was high (87%).

Several studies measured VEGF concentrations in people with or without obesity. We performed a subgroup meta-analysis of studies including people with obesity (Fig. 4). This meta-analysis included 12 study arms from four individual studies. Neither VEGF-A nor VEGF-D expression was increased in people with obesity (SMD = 0.66; 95% CI − 0.17, 1.49; p = 0.12) and (SMD = 0.84; 95% CI − 1.33, 3.00; p = 0.45), respectively. Whereas, the studies in people with obesity that measured VEGF-B (p = 0.006) and VEGF-C (p = 0.03) showed statistically significantly higher VEGF-B or C protein expression in people with obesity. Heterogeneity as measured by I2 varied from 0% (VEGF-C) to 95% (VEGF-D). The latter was driven entirely by Gomez-Ambrosi 2010 [9].

Hypertension is an important component of metabolic syndrome. One study looked at the effect of hypertension in children with type 1 diabetes (Fig. 5). Compared with healthy children, VEGF concentrations were much higher in children with type 1 diabetes and hypertension (SMD = 2.34, 95% CI 1.55, 3.12, p < 0.0001). Similarly, hypertension was strongly associated with increased VEGF concentrations even compared with children with type 1 diabetes and normal blood pressure (SMD = 1.62, 95% CI 1.03, 2.21, p < 0.0001). We intended to analyse the correlation of hypertension with different VEGF proteins, but due to a lack of studies we weren’t able to perform this analysis.

Hyperglycemia, either as part of diabetes or impaired glucose tolerance (pre-diabetes), is another important component of metabolic syndrome. We included 11 study arms from 8 individual studies (Fig. 6), all of which measured VEGF-A. The analysis of studies comparing those with type 2 diabetes and healthy controls demonstrated a strong association between hyperglycemia and increased VEGF expression (SMD = 0.69, 95% CI 0.34, 1.04; p = 0.0001), although heterogeneity was high (I2 = 83%). When comparing people with type 2 diabetes and people with impaired glucose tolerance, a significant increase in VEGF was still observed (SMD = 0.71, 95% CI 0.17, 1.25, p = 0.01). We intended to analyse the correlation of hyperglycemia with different VEGF proteins, but due to a lack of this studies we weren’t able to perform this analysis.

There were no studies specifically targeting patients with hypertriglyceridemia. However, we took the four studies in people with high triglycerides in addition to other conditions and undertook a meta-analysis (Fig. 7). The meta-analysis of the five included study arms was associated with a significant increase in VEGF-A expression (SMD = 0.65, 95% CI 0.14, 1.15, p = 0.01). Heterogeneity was high (I2 = 89%).

There were no studies specifically targeting patients with raised LDL-cholesterol. We therefore took the two studies in people with high LDL-cholesterol in addition to other conditions and undertook a meta-analysis (Fig. 8). The meta-analysis of these studies did not show an association between high LDL-C and higher VEGF expression (SMD = 0.31, 95% CI − 0.37, 0.99, p = 0.36). Heterogeneity was moderate (I2 = 69%). There were no studies in people with low HDL-cholesterol.

As stated earlier, we intended to undertake subgroup or sensitivity analysis based on concomitant medication, funding source, age of participants, co-morbidities of participants and gender of participants. Due to the paucity of data, we could only undertake subgroup analyses by funding source (Fig. 9), gender (Fig. 10) and age (Fig. 11). There were no significant differences between any subgroups. The differences in plasma compared with serum VEGF led us to undertake a post hoc sensitivity analysis of VEGF-A. Removing the studies that measured plasma VEGF-A from the overall analysis (thus including serum VEGF-A only) led to a slight increase in the SMD (0.63, 95% CI 0.45, 0.80, p < 0.0001) and a reduction of the heterogeneity as measured by I2 from 50 to 11%. The studies measuring plasma VEGF-A concentrations resulted in a smaller standardized mean difference that was also statistically significant (SMD = 0.44, 95% CI 0.06, 0.81, p = 0.02).

Association of VEGFs with metabolic syndrome or its components—qualitative results

VEGF in some studies was not normally distributed. In these cases, the data were reported as medians and interquartile ranges. Although it is possible to approximate a standard deviation from such data, it is not recommended [51]. Nevertheless, such data can provide valuable additional support to meta-analyzed data. Table 3 contains studies that could not be included in the meta-analysis. The ratio between the median VEGF concentration in the metabolic syndrome cohort and the control cohort was calculated. In the majority of studies, the ratio was greater than 1 (range 0.47–2.72), suggesting that VEGF concentrations were higher in people with component of metabolic syndrome or the metabolic syndrome itself.

Publication bias

In order to determine if publication bias exists, we undertook a funnel plot analysis (Fig. 12). Overall, the plot appears to be largely symmetrical, although it is possible that some low-quality studies showing increased VEGF expression were missing. We undertook the random effects version Egger’s regression test [18] to assess funnel plot asymmetry based on standard error. The test did not indicate any evidence of asymmetry (p = 0.67).

Discussion

Both quantitative and qualitative data from our study suggest that VEGF-A is overexpressed in the presence of metabolic syndrome. Further, our subgroup analyses show that with increasing disease, the concentration of VEGF proteins increases. That is, for example, the difference in VEGF-A expression in healthy children compared with children with type 1 diabetes and hypertension is greater than the difference between children with type 1 diabetes and those with type 1 diabetes and hypertension. This finding is not unexpected, as VEGF-A is known for its proangiogenic effects.

Interestingly, the subgroup analysis identified a significant association between increased levels of VEGF-A and hyperglycemia, but not obesity. The latter represents a very surprising finding, as angiogenesis is a process involved in adipose tissue expansion that takes place in obesity [5, 52]. Nonetheless, given the fact that the cohort of obese patients included in the quantitative analysis mostly did not suffer from metabolic complications, the authors speculate that, in conditions of preserved insulin sensitivity, obesity is not a stimulus strong or effective enough to stimulate VEGF-A expression. It is known that hypoxia is one the strongest stimuli for VEGF-A expression, thus, in the absence of IR-induced vasoconstriction and consequent hypoxia, VEGF-A may remain within its physiological limits However, although on a small cohort of patients, our study showed significantly increased levels of the angiogenic and lymphangiogenic factors VEGF-B and VEGF-C in obese patients, which may suggest that the heterogeneity among studies that addressed VEGF-A expression may have influenced the obtained results. Our finding of a correlation between VEGF-B and obesity corresponds to the findings observed by Robciuc et al. They observed that increased VEGF-B expression in the adipose tissue of a Vegfb transgenic mouse model increased capillary density, tissue perfusion, and insulin supply by the binding of VEGF-B to VEGFR1, which then activates the VEGF-A/VEGFR2 pathway [11]. On the other hand, VEGF-B is a key trans-endothelial FA regulator and as such, it would be expected for its expression to decrease in response to high amounts of circulating FAs [53, 54]. While it is possible that increased VEGF-B signaling is responsible for the pathological lipid accumulation in obese patients, further research is needed to elucidate this hypothesis.

The mechanism of the interaction between VEGF-A and LDL-C is still largely unknown. Our study did not identify a significant increase of VEGF-A levels in patients with high LDL-C levels, and this finding may be a result of the fact that the participants had differences in other comorbidities, or that the trans-endothelial transport of LDL-C is not influenced and does not depend on the presence of VEGF-A in the cell culture medium, as recently shown by Velagapudi et al. [55]. This may explain the earlier findings of Sandhofer et al. who failed to detect any association between VEGF-A levels and carotid atherosclerosis [56]. Further studies are needed to elucidate the exact behavior of VEGF-A and its correlation with LDL-C.

Mechanistically, it appears that the propensity towards higher concentrations of VEGF-A is, at least in part, genetically determined. Recently, Ghazizadeh et al. examined the association of a mutation in the VEGFA gene. They found association with an A-to-G mutation in the rs10738760 SNP and metabolic syndrome [57]. Interestingly, it appears that increased VEGF expression could both be a response to and a cause of increasing disease. However, this study was retrospective, and longitudinal studies will be required to elucidate the role of the VEGFs as a causative agent of disease.

Despite the somewhat heterogeneous nature of the available data, our study strongly suggests that expression of VEGFs differs among patients with metabolic syndrome. Although the regulation of the expression of VEGF proteins in preserved and impaired insulin signalling conditions remains largely unknown, our data synthesize the available evidence for the first time and provide a numerical estimate of the above-mentioned differences. The data from our meta-analyses are further supported by qualitative data, specifically by the ratio between the median VEGF concentration in the metabolic syndrome cohorts and the control cohorts. This ratio was greater than 1 in most of the studies (range 0.47–2.72), suggesting that VEGF concentrations were higher in people with a component of metabolic syndrome or the metabolic syndrome itself. This effect was particularly pronounced in the case of hypertriglyceridemia, with 7 out 8 included cohorts presenting ratios greater than 1 in favor of the high triglycerides cohort. The ratio between VEGF concentrations in the high LDL cohort and the control cohort was greater than 1 in all of the included studies (3/3) with two-fold increased VEGF concentrations in 2 out 3 studies. It has been shown that both VEGF-A and VEGF-B have the potential to increase vessel perfusion in obese adipose tissue, while VEGF-C and VEGF-D have lymphangiogenic properties [5, 11, 12, 46, 52]. In a pro-inflammatory milieu of excess FAs and/or glucose as found in obese and IR patients, the properties of these proteins are vital for two reasons: (1) enhanced vascularity increases the availability of insulin to target organs and improves insulin sensitivity, and (2) insulin-induced capillary recruitment and increased blood flow facilitate glucose uptake in target organs [58]. This especially refers to VEGF-A, which has been found to reduce metabolic complications caused by a high-fat diet and in the metabolic syndrome, through enhanced vascularity, thermogenesis and a decrease in inflammation [5, 52].

Interestingly, the expression of VEGFs in plasma and serum differs. When Hanefeld et al. examined the association of serum and plasma VEGF-A with type 2 diabetes [23], they found an order of magnitude difference in the concentration of VEGF-A in serum vs plasma. The serum concentrations of VEGF-A were 336 and 492 ng/l in control and type 2 diabetes patients, respectively. The difference between the groups was highly significant (p < 0.001). In contrast, the plasma VEGF-A concentrations in control and type 2 diabetes patients were 67.87 and 67.02 ng/l (p = 0.66) [23]. The authors suggested that the difference between serum and plasma VEGF-A concentrations is the result of VEGF-A accumulation in activated platelets [23]. We tested this hypothesis with a sensitivity analysis. Indeed, our results showed that removal of studies using plasma VEGF concentrations increased the SMD between patient and control groups.

Strengths and limitations

We acknowledge the limitations in our study. Firstly, there was significant heterogeneity among the 16 studies on VEGF-A (I2= 50%) and 2 studies on VEGF-D (I2= 91%), included in this meta-analysis. This suggests that there were differences between studies that cannot be accounted for by chance; for example, co-morbidities, medication use, age or others. Unfortunately the lack of studies prevented us from investigating this heterogeneity more thoroughly. Secondly, the study populations of the included studies were small in number and this may restrict the generalization of our findings. However, these results should be regarded as preliminary. The strength of this meta-analysis lies in the fact that it is the first to explore the correlation between VEGFs overexpression and metabolic syndrome or its components, and in the significant number of studies reporting on the expression of VEGF-A.

Conclusion

Overall the findings of this study demonstrate the strong association of increase in VEGFs expression with metabolic syndrome as well as its components. Our data strongly suggest overexpression of VEGF-A in patients with metabolic syndrome, hyperglycemia, hypertriglyceridemia and hypertension, but not obesity and high LDL. Preliminary data on the lymphangiogenic factors VEGF-C and VEGF-D suggest there are significantly increased and significantly decreased levels of these two proteins in metabolic syndrome or its components, respectively. However, further clinical studies on the association for the components of metabolic syndrome and VEGFs with the potential to adjust for confounding factors are encouraged.

References

Kaur J. A comprehensive review on metabolic syndrome. Cardiol Res Pract. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/943162.

Muniyappa R, Iantorno M, Quon MJ. An integrated view of insulin resistance and endothelial dysfunction. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2008;37:685–711. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecl.2008.06.001.

Olofsson B, Korpelainen E, Pepper MS, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor B (VEGF-B) binds to VEGF receptor-1 and regulates plasminogen activator activity in endothelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:11709–14.

Holmes DIR, Zachary I. The vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) family: angiogenic factors in health and disease. Genome Biol. 2005;6:209. https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2005-6-2-209.

Elias I, Franckhauser S, Ferré T, et al. Adipose tissue overexpression of vascular endothelial growth factor protects against diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2012;61:1801–13. https://doi.org/10.2337/db11-0832.

Miyazawa-Hoshimoto S, Takahashi K, Bujo H, et al. Elevated serum vascular endothelial growth factor is associated with visceral fat accumulation in human obese subjects. Diabetologia. 2003;46:1483–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-003-1221-6.

García de la Torre N, Rubio MA, Bordiú E, et al. Effects of weight loss after bariatric surgery for morbid obesity on vascular endothelial growth factor-A, adipocytokines, and insulin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:4276–81. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2007-1370.

Zafar MI, Zheng J, Kong W, et al. The role of vascular endothelial growth factor-B in metabolic homoeostasis: current evidence. Biosci Rep. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1042/bsr20171089.

Gomez-Ambrosi J, Catalan V, Rodriguez A, et al. Involvement of serum vascular endothelial growth factor family members in the development of obesity in mice and humans. J Nutr Biochem. 2010;21:774–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnutbio.2009.05.004.

Tinahones FJ, Coin-Araguez L, Mayas MD, et al. Obesity-associated insulin resistance is correlated to adipose tissue vascular endothelial growth factors and metalloproteinase levels. BMC Physiol. 2012;12:4. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6793-12-4.

Robciuc MR, Kivela R, Williams IM, et al. VEGFB/VEGFR1-induced expansion of adipose vasculature counteracts obesity and related metabolic complications. Cell Metab. 2016;23:712–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2016.03.004.

Karaman S, Hollmén M, Robciuc MR, et al. Blockade of VEGF-C and VEGF-D modulates adipose tissue inflammation and improves metabolic parameters under high-fat diet. Mol Metab. 2015;4:93–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmet.2014.11.006.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000100. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100.

Thomas J, Brunton J, Graziosi S. EPPI-Reviewer 4.0: software for research synthesis. London: EPPI-Centre Software, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London; 2010.

Study Quality Assessment Tools | National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools. Accessed 12 Feb 2018.

Rohatgi A. WebPlotDigitizer. Texas: Austin; 2017.

The Nordic Cochrane Centre. Review manager (RevMan). Copenhagen: The Cochrane Collaboration; 2014.

Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–34. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629.

Viechtbauer W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J Stat Softw. 2010. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v036.i03.

Du J, Li R, Xu L, et al. Increased serum chemerin levels in diabetic retinopathy of type 2 diabetic patients. Curr Eye Res. 2016;41:114–20. https://doi.org/10.3109/02713683.2015.1004718.

Erman H, Gelisgen R, Cengiz M, et al. The association of vascular endothelial growth factor, metalloproteinases and their tissue inhibitors with cardiovascular risk factors in the metabolic syndrome. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2016;20:1015–22.

Guo L, Jiang F, Tang Y-T, et al. The association of serum vascular endothelial growth factor and ferritin in diabetic microvascular disease. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2014;16:224–34. https://doi.org/10.1089/dia.2013.0181.

Hanefeld M, Appelt D, Engelmann K, et al. Serum and plasma levels of vascular endothelial growth factors in relation to quality of glucose control, biomarkers of inflammation, and diabetic nephropathy. Horm Metab Res. 2016;48:529–34. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0042-106295.

Jain A, Saxena S, Khanna VK, et al. Status of serum VEGF and ICAM-1 and its association with external limiting membrane and inner segment-outer segment junction disruption in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Mol Vis. 2013;19:1760–8.

Jesmin S, Akter S, Rahman MM, et al. Disruption of components of vascular endothelial growth factor angiogenic signalling system in metabolic syndrome. Findings from a study conducted in rural Bangladeshi women. Thromb Haemost. 2013;109:696–705. https://doi.org/10.1160/th12-09-0654.

Kakizawa H, Itoh M, Itoh Y, et al. The relationship between glycemic control and plasma vascular endothelial growth factor and endothelin-1 concentration in diabetic patients. Metabolism. 2004;53:550–5.

Kubisz P, Chudy P, Stasko J, et al. Circulating vascular endothelial growth factor in the normo- and/or microalbuminuric patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Acta Diabetol. 2010;47:119–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00592-009-0127-2.

Lim HS, Blann AD, Chong AY, et al. Plasma vascular endothelial growth factor, angiopoietin-1, and angiopoietin-2 in diabetes: implications for cardiovascular risk and effects of multifactorial intervention. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:2918–24.

Litvinova L, Atochin D, Vasilenko M, et al. Role of adiponectin and proinflammatory gene expression in adipose tissue chronic inflammation in women with metabolic syndrome. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2014;6:137. https://doi.org/10.1186/1758-5996-6-137.

Loebig M, Klement J, Schmoller A, et al. Evidence for a relationship between VEGF and BMI independent of insulin sensitivity by glucose clamp procedure in a homogenous group healthy young men. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e12610. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0012610.

MacEneaney OJ, Kushner EJ, Westby CM, et al. Endothelial progenitor cell function, apoptosis, and telomere length in overweight/obese humans. Obesity. 2010;18:1677–82. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2009.494.

Mahdy RA, Nada WM. Evaluation of the role of vascular endothelial growth factor in diabetic retinopathy. Ophthalmic Res. 2011;45:87–91. https://doi.org/10.1159/000317062.

Marek N, Mysliwiec M, Raczynska K, et al. Increased spontaneous production of VEGF by CD4+ T cells in type 1 diabetes. Clin Immunol. 2010;137:261–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clim.2010.07.007.

Mirhafez SR, Pasdar A, Avan A, et al. Cytokine and growth factor profiling in patients with the metabolic syndrome. Br J Nutr. 2015;113:1911–9. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0007114515001038.

Mirhafez SR, Tajfard M, Avan A, et al. Association between serum cytokine concentrations and the presence of hypertriglyceridemia. Clin Biochem. 2016;49:750–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2016.03.009.

Mysliwiec M, Balcerska A, Zorena K, et al. The role of vascular endothelial growth factor, tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin-6 in pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2008;79:141–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2007.07.011.

Nandy D, Mukhopadhyay D, Basu A. Both vascular endothelial growth factor and soluble Flt-1 are increased in type 2 diabetes but not in impaired fasting glucose. J Investig Med. 2010;58:804–6.

Ozturk BT, Bozkurt B, Kerimoglu H, et al. Effect of serum cytokines and VEGF levels on diabetic retinopathy and macular thickness. Mol Vis. 2009;15:1906–14.

Ruszkowska-Ciastek B, Sokup A, Socha MW, et al. A preliminary evaluation of VEGF-A, VEGFR1 and VEGFR2 in patients with well-controlled type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2014;15:575–81. https://doi.org/10.1631/jzus.b1400024.

Schlingemann RO, Van Noorden CJF, Diekman MJM, et al. VEGF levels in plasma in relation to platelet activation, glycemic control, and microvascular complications in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:1629–34. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc12-1951.

Seckin D, Ilhan N, Ilhan N, Ertugrul S. Glycaemic control, markers of endothelial cell activation and oxidative stress in children with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2006;73:191–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2006.01.001.

Siervo M, Ruggiero D, Sorice R, et al. Angiogenesis and biomarkers of cardiovascular risk in adults with metabolic syndrome. J Intern Med. 2010;268:338–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2796.2010.02255.x.

Siervo M, Ruggiero D, Sorice R, et al. Body mass index is directly associated with biomarkers of angiogenesis and inflammation in children and adolescents. Nutr Burbank Los Angel Cty Calif. 2012;28:262–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2011.06.007.

Silha JV, Krsek M, Hana V, et al. The effects of growth hormone status on circulating levels of vascular growth factors. Clin Endocrinol Oxf. 2005;63:79–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2265.2005.02303.x.

Suguro T, Watanabe T, Kodate S, et al. Increased plasma urotensin-II levels are associated with diabetic retinopathy and carotid atherosclerosis in Type 2 diabetes. Clin Sci. 2008;115:327–34. https://doi.org/10.1042/cs20080014.

Valabhji J, Dhanjil S, Nicolaides AN, et al. Correlation between carotid artery distensibility and serum vascular endothelial growth factor concentrations in type 1 diabetic subjects and nondiabetic subjects. Metabolism. 2001;50:825–9.

Wada H, Satoh N, Kitaoka S, et al. Soluble VEGF receptor-2 is increased in sera of subjects with metabolic syndrome in association with insulin resistance. Atherosclerosis. 2010;208:512–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.07.045.

Wu J, Wei H, Qu H, et al. Plasma vascular endothelial growth factor B levels are increased in patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus and associated with the first phase of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion function of beta-cell. J Endocrinol Invest. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40618-017-0677-z.

Zorena K, Myśliwska J, Myśliwiec M, et al. Association between vascular endothelial growth factor and hypertension in children and adolescents type I diabetes mellitus. J Hum Hypertens. 2010;24:755–62. https://doi.org/10.1038/jhh.2010.7.

Doupis J, Rahangdale S, Gnardellis C, et al. Effects of diabetes and obesity on vascular reactivity, inflammatory cytokines, and growth factors. Obesity. 2011;19:729–35. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2010.193.

7.7.3.5 Medians and interquartile ranges. http://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org/chapter_7/7_7_3_5_mediansand_interquartile_ranges.htm. Accessed 1 Feb 2018.

Sun CY, Lee CC, Hsieh MF, et al. Clinical association of circulating VEGF-B levels with hyperlipidemia and target organ damage in type 2 diabetic patients. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2014;28:225–36.

Hagberg CE, Falkevall A, Wang X, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor B controls endothelial fatty acid uptake. Nature. 2010;464:917–21. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature08945.

Hagberg CE, Mehlem A, Falkevall A, et al. Targeting VEGF-B as a novel treatment for insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2012;490:426–30. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11464.

Velagapudi S, Yalcinkaya M, Piemontese A, et al. VEGF-A regulates cellular localization of SR-BI as well as transendothelial transport of HDL but not LDL. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2017;37:794–803. https://doi.org/10.1161/atvbaha.117.309284.

Sandhofer A, Tatarczyk T, Kirchmair R, et al. Are plasma VEGF and its soluble receptor sFlt-1 atherogenic risk factors? Cross-sectional data from the SAPHIR study. Atherosclerosis. 2009;206:265–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.01.031.

Ghazizadeh H, Fazilati M, Pasdar A, et al. Association of a vascular endothelial growth factor genetic variant with serum VEGF level in subjects with metabolic syndrome. Gene. 2017;598:27–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gene.2016.10.034.

Rafii S, Carmeliet P. VEGF-B improves metabolic health through vascular pruning of fat. Cell Metab. 2016;23:571–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2016.03.012.

Authors' contributions

MIZ conceptualized the topic, outlining the review questions, interpreting the results, initial drafting and finalizing the manuscript. KM and YXF conducted the systematic search on bibliographic databases for article retrieval and preliminary selection of articles. MJ and BB did the selection of articles and data extraction. WK and NZ performed the quality assessment of included studies, AR and SQH re-evaluated the selection of articles, study quality and confirmed the accuracy of extracted data. KM and JZ performed the statistical analysis and JZ provided supervision in the study conduct. KM resolved the issues pertaining to the study quality, data extraction, and study selection. CLL reviewed the intellectual concept of the article, revised the content for intellectual content, and finalized the article. KM, YXF, MJ and BB contributed in writing of introduction and methodology. WK, NZ, AR and SQH contributed in writing of results and discussion. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We thank Peter Mere for carrying out the Egger’s test for publication bias.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The current study is systematic review and meta-analysis, data used in the study is from published research reports on the topic.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Funding sources

None of the study authors received industry funding for this study. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [Grant Number 81471069] and Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province, China [Grant Number 2016CFA025]. The funding bodies are public institutions and had no role in study design, conduct or interpretation of results.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Zafar, M.I., Mills, K., Ye, X. et al. Association between the expression of vascular endothelial growth factors and metabolic syndrome or its components: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetol Metab Syndr 10, 62 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-018-0363-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-018-0363-0