Abstract

Background

Good syndrome is a rare condition, manifesting as immunodeficiency due to hypogammaglobulinemia associated with thymoma. Herein, we present a patient with Good syndrome whose thymoma was resected after treatment of cytomegalovirus hepatitis.

Case presentation

The patient was a 45-year-old woman presenting with fever, cough, and nasal discharge, and was diagnosed with thymoma and hypogammaglobulinemia. She subsequently developed cytomegalovirus hepatitis that was treated by immunoglobulin. After resolution of the hepatitis, she underwent thymectomy through a left anterior thoracotomy. Her postoperative course was uneventful, and while receiving ongoing immunoglobulin therapy, she has been doing well without signs of infection.

Conclusions

Management of infections is important for patients with Good syndrome. To minimize the risk of perioperative infection, we should take care while planning the surgical approach and procedure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Good syndrome, the condition of adult-onset immunodeficiency associated with thymoma, is quite rare, occurring in only 0.2–6% of thymoma patients [1, 2]. Patients with typical Good syndrome show hypogammaglobulinemia and B-cell depletion. Preventing infection improves the prognosis of patients with Good syndrome, and repeated gamma globulin therapy is considered necessary [3, 4]. Herein, we report a patient with Good syndrome who underwent successful resection of her thymoma through a left anterior thoracotomy and received preoperative gamma globulin therapy subsequent to treatment for preoperative cytomegalovirus hepatitis.

Case presentation

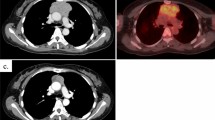

The patient was a 45-year-old woman who was referred to a nearby clinic for fever of 38 °C, cough, and nasal discharge. Although she was treated with antibiotics, her signs were not improved. Chest X-ray and computed tomography showed a 61 × 45-mm anterior mediastinal tumor (Fig. 1). Positron emission tomography scan showed 1.8-fold greater uptake than the maximal standardized uptake value in the tumor. A blood test revealed a serum immunoglobulin G level of 239 mg/dL (normal range 870–1700 mg/dL), serum immunoglobulin A level of 24 mg/dL (normal range 110–410 mg/dL), and a serum immunoglobulin M level of 26 mg/dL (normal range 46–260 mg/dL). She was referred to our hospital for further examination and treatment for the anterior mediastinal tumor and hypogammaglobulinemia. The histopathological diagnosis of a CT-guided biopsy specimen was type AB thymoma based on the World Health Organization classification, leading to the diagnosis of Good syndrome.

While undergoing diagnostic workup, the patient developed sudden deafness that was treated by corticosteroids. She then became febrile with worsening liver function, showing a serum aspartate aminotransferase level of 127 U/L and a serum alanine aminotransferase level of 132 U/L. She developed serum cytomegalovirus antigenemia, and altogether, the findings were diagnosed as cytomegalovirus hepatitis due to hypogammaglobulinemia. She received 15 g of immunoglobulin and ganciclovir with subsequent improvement in her liver function, with normal serum levels of aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase. Her serum cytomegalovirus antigenemia was undetectable 2 weeks after initiation of antiviral therapy.

After her cytomegalovirus hepatitis improved, the patient underwent surgical resection for thymoma. Because she was immunocompromised, we performed a video-assisted left anterior thoracotomy with an 8 cm skin incision instead of a median sternotomy to minimize the risk of a perioperative infection (Fig. 2). We administered immunoglobulin twice before surgery, and thymectomy was performed 3 months after the diagnosis of cytomegalovirus hepatitis. The postoperative course was uneventful without signs of infection, and the patient was discharged 10 days after the surgery. Macroscopically, the tumor was encapsulated grayish-white mass with a size of 80x42x63mm (Fig. 3a). Pathological diagnosis showed type AB thymoma (Fig. 3b).

Operative specimen. (a) Macroscopically, the tumor was encapsulated grayish-white mass with a size of 80x42x63mm. (b) Microscopic picture. Hematoxylin and eosin stain 200X. The tumor was consist of a variable mixture of lymphocyte-poor type A-like components and lymphocyte-rich type B-like components

The patient remains alive without recurrence of thymoma for 26 months. Her hypogammaglobulinemia has persisted, and she has undergone regular administration of immunoglobulin therapy (Fig. 4). She has not developed signs of infection since the immunoglobulin therapy was initiated. Sudden deafness was not improved by corticosteroids. Six months after thymectomy, the cochlear implant was performed for deafness.

Discussion

Good syndrome is characterized as a combination of thymoma and hypogammaglobulinemia. In patients with Good syndrome, hypogammaglobulinemia often results in bacterial and viral infections, which are sometimes fatal [3, 4]. Therefore, the control of infection is important in patients with Good syndrome.

Bacterial infections are the most frequent in patients with the Good syndrome, followed by viral infections, with cytomegalovirus infection being the most frequent viral infection [4]. Cytomegalovirus duodenoenteritis and retinitis have been reported in patients with Good syndrome [5, 6]. According to these previous reports, ganciclovir was an effective treatment.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of cytomegalovirus hepatitis in a patient with Good syndrome. Cytomegalovirus hepatitis sometimes occurs in immunodeficient patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection or undergoing organ transplantation. Cytomegalovirus infection can relapse after improvement due to ganciclovir treatment, if the patient’s immunodeficiency worsens. In our case, the use of corticosteroids in addition to hypogammaglobulinemia induced relapse of cytomegalovirus infection. Therefore, we administered immunoglobulin therapy before and after the patient’s thymectomy to prevent relapse of hepatitis during the perioperative period, and long after the surgery.

The prevention of surgical site infection during the perioperative period is also important. We administered immunoglobulin therapy before the operation and after the operation prophylactic intravenous antibiotics for a week. In addition, we performed a video-assisted left anterior thoracotomy for a left anterior mediastinal tumor instead of a median sternotomy. Mediastinitis is a complication after sternotomy, and postoperative mediastinitis was previously reported in a patient with Good syndrome who underwent thymectomy through a median sternotomy [7]. Therefore, we avoided performing it. Although a thoracoscopic approach is another option, we performed a thoracoscopy-assisted lateral thoracotomy because the tumor diameter was at least 6 cm. It was recently reported that thymectomy alone is appropriate for patients with stage I thymoma [8]. To minimize the risk of postoperative infection, we think thymectomy through a lateral thoracotomy is reasonable for patients with Good syndrome with stage I thymoma.

Conclusion

Management of infections is important for patients with Good syndrome. To minimize the risk of perioperative infection, we should take care while planning the surgical approach and procedure.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

References

Jansen A, van Deuren M, Miller J, Litzman J, de Gracia J, Sáenz-Cuesta M, et al. Good syndrome study group. Prognosis of good syndrome: mortality and morbidity of thymoma associated immunodeficiency in perspective. Clin Immunol. 2016;171:12–7.

Malphettes M, Gérard L, Galicier L, Boutboul D, Asli B, Szalat R, et al. Good syndrome: an adult-onset immunodeficiency remarkable for its high incidence of invasive infections and autoimmune complications. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61:e13–9.

Thongngarm T, Boonyasiri A, Pradubpongsa P, Tesavibul N, Anekpuritanang T, Kreetapirom P, et al. Features and outcomes of immunoglobulin therapy in patients with good syndrome at Thailand's largest tertiary referral hospital. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2019;37:109–15.

Tarr PE, Sneller MC, Mechanic LJ, Economides A, Eger CM, Strober W, et al. Infections in patients with immunodeficiency with thymoma (good syndrome). Report of 5 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2001;80:123–33.

Koriyama N, Fukumoto O, Fukudome M, Aso K, Hagiwara T, Arimura K, et al. Successful treatment of good syndrome with cytomegalovirus duodenoenteritis using a combination of ganciclovir and immunoglobulin with high anti-cytomegalovirus antibody titer. Am J Med Sci. 2004;327:49–54.

Park DH, Kim SY, Shin JP. Bilateral cytomegalovirus retinitis with unilateral optic neuritis in good syndrome. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2010;54:246–8.

Kitamura A, Takiguchi Y, Tochigi N, Watanabe S, Sakao S, Kurosu K, et al. Durable hypogammaglobulinemia associated with thymoma (good syndrome). Intern Med. 2009;48:1749–52.

Nakagawa K, Yokoi K, Nakajima J, Tanaka F, Maniwa Y, Suzuki M, et al. Is Thymomectomy alone appropriate for stage I (T1N0M0) Thymoma? Results of a propensity-score analysis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;101:520–6.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SI, AS, HO, YA, SK, TMak, TS and AI participated in the surgical procedure. TI, TMae and SH treated infectious diseases. KE performed a pathological diagnosis. SI and AS wrote the manuscript. AI supervised this research. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for this case report.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

None of the listed authors has any financial or other interests that could be a conflict.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Isobe, S., Sano, A., Otsuka, H. et al. Good syndrome with cytomegalovirus hepatitis: successful resection of Thymoma: a case report. J Cardiothorac Surg 15, 141 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13019-020-01187-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13019-020-01187-y