Abstract

Introduction

The Lancet Commission for Global Surgery identified an adequate surgical workforce as one indicator of surgical care accessibility. Many countries where women in surgery are underrepresented struggle to meet the recommended 20 surgeons per 100,000 population. We evaluated female surgeons’ experiences globally to identify strategies to increase surgical capacity through women.

Methods

Three database searches identified original studies examining female surgeon experiences. Countries were grouped using the World Bank income level and Global Gender Gap Index (GGGI).

Results

Of 12,914 studies meeting search criteria, 139 studies were included and examined populations from 26 countries. Of the accepted studies, 132 (95%) included populations from high-income countries (HICs) and 125 (90%) exclusively examined populations from the upper 50% of GGGI ranked countries. Country income and GGGI ranking did not independently predict gender equity in surgery. Female surgeons in low GGGI HIC (Japan) were limited by familial support, while those in low income, but high GGGI countries (Rwanda) were constrained by cultural attitudes about female education. Across all populations, lack of mentorship was seen as a career barrier. HIC studies demonstrate that establishing a critical mass of women in surgery encourages female students to enter surgery. In HICs, trainee abilities are reported as equal between genders. Yet, HIC women experience discrimination from male co-workers, strain from pregnancy and childcare commitments, and may suffer more negative health consequences. Female surgeon abilities were seen as inferior in lower income countries, but more child rearing support led to fewer women delaying childbearing during training compared to North Americans and Europeans.

Conclusion

The relationship between country income and GGGI is complex and neither independently predict gender equity. Cultural norms between geographic regions influence the variability of female surgeons’ experiences. More research is needed in lower income and low GGGI ranked countries to understand female surgeons’ experiences and promote gender equity in increasing the number of surgical providers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the modern era of medicine, Elizabeth Blackwell was the first reported woman to graduate from medical school in 1849 and pursue a career in surgery [1]. Women pursuing careers in medicine has steadily increased with women now representing 50% of current medical school matriculants in the United States (US) [2]. This shift is not reflected to the same extent in surgical specialties, where women have experienced much slower growth [1]. In the United Kingdom (UK) and the US, men are 73% and 61.6% of practicing surgeons, respectively [3, 4]. The number of female surgeons in low- and middle-income countries rose disproportionately slower than female representation in other medical specialties [5,6,7]. Concurrently, five-billion people lack access to safe, affordable surgical care globally and many countries need an increase in surgical providers to reach the recommended 20 per 100,000 population [6]. With the majority of low- and middle-income countries struggling to build an adequate surgical workforce, expanding the participation of women in surgery is a powerful way to help alleviate the global burden of surgery [6, 7].

The experiences of women in medicine and how they differ from men is well documented. The majority of this work has focused on barriers such as discrimination, pay gaps, and promotion inequality [8,9,10,11]. Surgery continues to be a male-dominated field with the disparate experiences between genders not well documented worldwide. Understanding career experiences of women in surgery is essential to expand the female workforce, improve the professional surgical environment, and retain existing female surgeons.

This scoping review seeks to understand the experiences of female surgeons around the world and how they differ based on geography, national income (World Bank income level) and cultural beliefs of gender equity (Global Gender Gap Index (GGGI)). The experience of female surgeons is a very broad topic for which we hope to synthesize the current knowledge and identify where gaps in gender equity are evident globally. Our analysis can inform future training programs and professional, educational and institutional initiatives and policies. We hope to inspire new strategies to increase surgical capacity through empowering women globally.

Methods

A scoping review was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [12] guidelines for reporting (Additional file 1). A detailed protocol has been provided as Additional file 2.

Research question

This review was led by the question, ‘What are the experiences of female surgeons around the world and how to do they differ based on geography, country income level, and cultural beliefs of gender equity?’ The female surgical experience was defined as any difference in attitude, treatment, behavior or career outcome that results from a surgeon’s female gender.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Included were original, peer-reviewed, full-text articles published in English that studied female surgeons, female surgical residents, and female medical students considering surgery. Topics required for inclusion were work–life balance, salary, health, job titles, career factors and barriers, training, skills, pregnancy, childrearing, domestic work, volunteerism, interpersonal interactions and discrimination/harassment. All study types were included, such as cross-sectional analysis, questionnaires, longitudinal analysis, and controlled trials. Editorials, case reports and personal anecdotes were excluded due to potential bias. No restriction was placed on the year of publication to assess the complete literature on female surgeons.

Search strategy, study selection and data collection

A search of PubMed, Web of Science, and MEDLINE (Ovid) was conducted on April 2, 2020 and included six search constructs (Table 1). One author (M.X.) conducted the initial review and excluded articles that did not meet inclusion criteria according to title. Two authors (M.X. and N.M.) reviewed the remaining study abstracts and excluded articles that did not meet inclusion criteria. The remaining articles were summarized in a chart in Microsoft Excel 2013 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA). Full-text articles were individually reviewed by two authors (M.X. and N.M.) to extract study characteristics including study design, publication year, study population countries and gender distribution, the category of the female surgical experience, funding source, and the study’s main findings. Studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded. Any inclusion discrepancies between authors was resolved through discussion. Data from included studies was compiled into a single spreadsheet for analysis independently.

Synthesis of results

Studies were sorted into four key categories based on main focus: careers challenges, residency and training, family and work–life balance, and other. The World Bank Income Level Group and GGGI ranking of included countries were recorded. The World Bank classifies countries into four categories according to gross national income per capita: low-income country (LIC), lower-middle income country (LMIC), upper-middle income country (UMIC), and high-income country (HIC) [13]. These income-level groupings indicate a country’s economic capabilities, associated resources, and opportunities that may be available to the population within. The Global Gender Gap Index is a weighted rating comprising of scores for economic participation and opportunity, educational attainment, health and survival, and political empowerment. GGGI ratings contextualize the experiences of women around the world in a social and professional capacity. Lower scores and rankings correspond to less equality for women [14]. Summary and descriptive statistics were calculated using Microsoft Excel 2013.

Results

The PubMed search yielded 12,914 total articles. A total of 12,775 articles were excluded as duplicates, having incorrect study focus, or not being original studies published in peer-reviewed journals (Fig. 1). The process yielded 139 studies meeting inclusion criteria and published between 1993 and 2020 (Fig. 1, Table 2). Of these 139 articles, 66% (n = 92) were published in 2015 or later (Table 2). Of the included articles, 47 (34%) focused on careers challenges, 37 (27%) on residency and training, 36 (26%) on family and work–life balance, and 19 (14%) on other topics (Fig. 1). The category of “other” included articles related to interpersonal interactions (n = 3), salary (n = 8), physical health (n = 5), demographics (n = 2), and international volunteerism (n = 1). Included study details appear in Table 2. The most common methodology of the articles was questionnaire (n = 77, 55.0%), cross-sectional (n = 23, 16.4%), and semi-structured or qualitative interview (n = 10, 7.4%).

Geography, World Bank income level and GGGI

Fifteen studies examined populations from multiple countries (Table 2). Most study populations originated from the North America (n = 103, 62.4%) and Europe (n = 31, 18.8%). Remaining study populations originated from Asia (n = 13, 7.9%), Oceania (n = 10, 6.1%), and Africa (n = 8, 4.8%) (Table 3). No studies evaluated female surgeons in Central or South America (Fig. 2, Table 3). Ninety-one percent (n = 127) of the studies exclusively examined populations from HICs (Table 2). Six studies (4%) exclusively examined populations from lower income countries (UMIC, LMIC, or LIC), whereas five studies (4%) evaluated populations from at least one HIC and one lower income country (Table 2). The country origins of the population in one study (1%) could not be determined [15]. Populations from HICs were represented in 95.0% of the studies (n = 132). Of the 26 countries represented, half (n = 13) were within the top 25% countries in the world for GGGI, and 73% (n = 19) fell within the top 50% of the 153 countries ranked by the index. One hundred and twenty-five (90%) studies exclusively examined populations from the top 50% of all GGGI ranked countries. Of the lower 50% of all countries rated by the GGGI, only 9% (n = 7) have study populations included in the current literature (Fig. 2, Table 4). Two countries, Japan, and Saudi Arabia were high-income economies with GGGI rankings in the bottom 50% of countries. One country, Rwanda, was a LIC ranked in the top 10 of GGGI ranked countries.

Careers challenges

Eighty-nine percent of articles (42 of 47 articles) focusing on career challenges studied only populations from HICs (Tables 2 and 3). Three articles (7%) studied populations from HICs, UMICs, and LMICs, while two articles (4%) studied only populations from LMICs (Tables 2 and 3). Forty-two (89%) of these 47 studies exclusively examined women from the top 50% of GGGI rated countries (Tables 2, 3 and 4). Female surgeons from different countries had different perceptions of their career barriers. US surgeons attributed their career barriers to ineffective mentorship, gender stereotypes, unclear expectations, a perceived lack of belonging, and sexism in the workplace [21, 22]. Barriers to career success in Europe were ineffective mentorship, gender stereotypes, a lack of part-time career availability, and work–family conflicts [23, 24]. In Nigeria, female surgeons listed limited time with family, workload, physical effort, a lack of women in surgery, and a lack of role models as deterrents from surgical careers [25].

Two studies recommend steps to increase women in surgery. Kass et al. reported the most important factors for academic success by US female surgeons was the pursuit of mentorship (60% of respondents), setting career goals (50% of respondents) and honing writing skills and publishing (50% of respondents) [26]. To achieve better gender balance in surgery, female and male surgeons in Zimbabwe recommended better working conditions, increasing female interest in surgery, increasing the number of female role models, and changing cultural/religious beliefs [27].

Residency and training

Thirty-seven studies focused on female surgeons in residency and training, with 86% (n = 32) of these articles exclusively describing HIC populations (Tables 2 and 3). Thirty-three (89%) of the articles this category focused only on the upper half of all GGGI rated countries (Tables 2 and 4). Two articles studied UMICs exclusively (South Africa by Umoetok et al.[28] and Turkey by Eyigor et al. [29]) and one article focused on a LIC, Rwanda [30]. Two studies examined populations from multiple income levels [15, 18].

Gender-based discrimination

Fifty-one percent (n = 19) of the articles reviewing residency and training, highlighted female surgical trainees’ challenges with gender-based discrimination [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46]. Gender-based discrimination was described as negative stereotyping, exclusion from networking, and physical, emotional and sexual harassment. Male colleagues were the perpetrators of 98% of reported harassment by female surgical residents in the US and 72% of these cases were from attending physicians [41]. In Canada, 25% of female medical students reported gender-based discrimination during their surgical clerkship, versus 3% of men; this discrimination was from surgeons (35%), surgical residents (25%), and nurses (17%) [33]. In the UK, 15% of female medical students were told by senior healthcare professionals that women should not be surgeons and 34% witnessed negative comments made about women as surgeons [44]. In Australia and New Zealand, the attrition of female surgical trainees was caused in part by bullying, sexual harassment, sexism, fear of repercussion, poor mental health, and a lack of support pathways [46]. In South Africa, an UMIC, 34% of female surgeons experienced physical threats, 40% experienced emotional threats, and 50% reported bullying [28]. Female surgical trainees in Turkey (an UMIC) were more likely to report gender-based discrimination if they were training in departments without female faculty (p < 0.006) [29]. Discrimination against female surgical trainees in Turkey was perpetrated by their seniors (68%), colleagues (25%), patients (6%) and hospital staff (1%) [29].

Gender differences in surgical skill

Three studies compared the surgical skills of male and female trainees in six HICs [47,48,49]. Two studies examining technical capabilities in bowel anastomoses and physical strength found no significant difference in male and female surgical residents’ capabilities [47, 48]. In Rwanda, 66.7% of male and 50% of female surgeons believed that women were physically and mentally weaker than men and therefore less able to perform surgeries [30]. One female surgeon reported that there was a biological basis for the gender disparity in surgery, stating that the difference was “testosterone. Men do not fear and female do fear” [30].

Mentorship

The impact and lack of mentorship in training were discussed in six articles from HICs [32, 36, 46, 50,51,52], one article from an UMIC (South Africa) [28], and one article from a LIC (Rwanda) [30]. One study from the US found that a significantly higher proportion of female medical students pursued surgery when their school had more female surgical role models (p < 0.0001) [50]. However, a qualitative survey in the US reported that 44% of female general surgery residents felt they lacked mentorship and that more mentorship for female surgeons is needed [36]. Similarly, in Canada, 80% of the female members of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons reported needing a female mentor [32]. The absence of interactions with other women in surgery was a noted reason why female trainees left surgical training in Australia and New Zealand [46]. Female surgeons in Japan had 3.6 mentors each on average, with 2.8 being male and 0.8 being female [52]. In South Africa, 75% of the female surgeons reported having a mentor, with 33.3% of their mentors being female [28]. In 22% (n = 7) of cases, respondents believed that the gender of their mentor made a difference in their training quality [28]. Rwanda had two female surgeons in the country as of 2018; role models for female surgical trainees in Rwanda were male surgeons and female peers [30].

Family and work–life balance

Thirty-six studies focused on family and work–life balance with 34 articles (94%) exclusively evaluating populations from HICs. Of the 34 articles with GGGI ranked populations, 29 articles (85%) solely studied populations from the upper half of all GGGI rated countries (Tables 2, 3, and 4). One study (3%) by Abolarinwa et al. exclusively studied Nigeria, a LMIC [53]. Another study evaluated HICs, UMICs (China and South Africa) and a LMIC (Nigeria) [19].

Pregnancy

Nineteen studies reported on the pregnancies of female surgeons [19, 53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70]. In the US, 27.5% of female surgeons had children during residency, compared with 62.4% after residency [70]. In Canada, 29.4% of female surgeons had children during residency, 7.7% prior to residency, and 55.2% after residency [62]. Female surgeons in the US who were pregnant during training reported feeling poorly judged (73.1%), pressured to schedule their pregnancies around training (55.1%), and that their work schedule negatively impacted their or their child’s health (63.3%) [65]. US female surgical trainees without children reported sadness when thinking about children (p = 0.047) and worry that they will never have children compared to male trainees (p < 0.0001) [67]. In contrast, female surgeons in Nigeria who had children gave birth more often during training (78.8%); 37.5% felt their pregnancy negatively impacted their training by increasing training time, straining relationships with instructors, or creating difficulty with scheduling outside rotations [53].

Maternity leave

Ten studies evaluated access to childcare and maternity leave policies for female surgeons from only HICs [54, 55, 57, 61,62,63, 66, 69,70,71]. A study by Walsh et al. included populations from the US, Canada, the UK, China, Sweden, Australia, Nigeria, and South Africa [19]. In this study, Chinese female surgeons were the least likely to reduce their workload while pregnant [19]. All Nigerian female surgeons reported their spouses could not receive paid paternity leave and 86% reported that their spouses were unlikely to get unpaid paternity leave [19].

Childcare and housework

Nine studies exclusively from HICs [57, 64, 70,71,72,73,74,75,76] found that women had a higher proportion of household and childcare responsibilities. Female surgeons from the US reported one to ten more hours of housework per week versus male surgeons [72]. In Germany, female surgeons spent 7.4% of their week running the household compared to 5.9% for male surgeons [70]. Female surgeons from Canada reported more hours of childcare per week compared to male surgeons (p < 0.0003) [74]. Twenty-seven percent of female surgeons in Switzerland completed all housework themselves [75]. In Hong Kong, more female surgeons reported having less time to rest than male surgeons (p = 0.038) [71]. Japanese female surgeons were more likely to report sacrificing career success or advancement for childbearing (p < 0.01); they had less family support for their careers than female surgeons from other countries (p < 0.01) [76]. Japanese female surgeons also had the least amount of personal time [76]. In Hong Kong, female surgeons reported less time for community participation and rest compared to male counterparts [71].

Health and other topics

Nineteen studies, all from HICs and the upper half of GGGI countries, focused on other topics: interpersonal interactions (n = 3), payment (n = 8), physical health (n = 5), demographics (n = 2), and international volunteerism (n = 1) (Fig. 1, Table 2). Female surgeons in Poland had shorter life expectancies than the general female population (77.5 vs 86.6 years) [77]. Norwegian female surgeons drank large quantities of alcohol more frequently than non-surgeon female physicians (18% vs. 7.6%) [78]. Compared to the general population in the US, breast cancer prevalence was significantly greater in female orthopedic surgeons (p < 0.001) [79]. US female surgeons were more likely to receive treatment for issues relating to their hands than males (p = 0.028), citing instrument design (84%) and operating room table height (44%) as the cause of their symptoms [80]. In the US, female surgeons earned over $60,000 less per year than male surgeons after controlling for work hours, case volume, years in practice, practice setting and specialty (p < 0.001) [81].

Discussion

To the author’s knowledge, this study reflects the only scoping review evaluating the experiences of female surgeons worldwide. The demographics of included studies alone provide unique insights into the literature on women in surgery. The majority of research on female surgeons was published in the past five years and focuses on women from the US or other HICs and high GGGI ranked countries. With only 26 countries in this review, we have demonstrated a large shortage of literature on female surgeons experiences compared to the reported 53 countries where female surgeons exist [19]. In particular, no literature on female surgeons was available from Central and South America, despite evidence of women working as surgeons in this region [82]. More importantly, this review has demonstrated that differences in culture, economic and educational opportunity, gender equity and women’s empowerment affect the experiences of both female surgical trainees and current female surgeons [3, 18, 83].

The first step in training and retaining more women in surgery is to support the current cohort of female surgeons worldwide, as female surgeons in North America, Europe, Oceania, Asia, and Africa identified lack of mentorship, particularly female mentorship, as a barrier to career advancement and a reason for attrition in surgical training [23, 27, 28, 30, 32, 36, 46, 52, 75]. One possible solution for this barrier is to increase the mentorship and visibility of women in surgical specialties, which has been demonstrated in the US to positively influence young women to enter surgical specialties [50]. Increasing the number of female surgeons through mentorship is less feasible in some countries. Despite evidence that women and men have equivalent physical strength and skills, the limited number of female surgeons currently in countries like Rwanda, along with the societal belief that women are less suited for the demands of surgery, limits the availability of mentors for new female surgeons [30, 47,48,49].

A country’s income and GGGI status can help frame the need to support their women in surgery. Rwanda is a LIC with a high ranking for global gender equality but very low ranking for educational attainment; negative attitudes towards female surgeons may stem from a deeper sociological mindset towards the educational achievements and career choices of women. Zimbabwe has a moderate GGGI ranking overall but a low ranking in educational attainment; there, both male and female surgeons believe that cultural and religious attitudes need to change in order to achieve gender equity in surgery [27]. In low-and-middle income countries with lower GGGI educational attainment rankings, working to change cultural attitudes about female education and stereotypical gender roles may be the first step towards increasing the prevalence of women in surgery.

Regardless of country income level, lower GGGI rankings can predict restrictive gender norms that limit female attainment in surgery. Populations from East Asia (Japan, Hong Kong, and China) had higher incomes (HIC and UMIC) and GGGI rankings in the lower 50%, particularly in economic participation. This dichotomy may highlight cultural structures less inclusive of female advancement. Unlike female surgeons from western countries, Japanese female surgeons reported less familial support for their careers and less leisure time. Seen as the responsibility primarily of women in countries with lower GGGI rankings and low female economic participation, domestic duties are in direct conflict with medical systems that rewards long hours and increased overtime work [76]. Therefore, the medical fields in countries with low GGGI rankings, regardless of income status, may be designed to favor the male workforce. Gender norms in these countries further strain female surgeons’ work–life balance and career attainment. Future initiatives in these countries should target cultural attitudes about women’s domestic roles and economic participation along with policies to increase flexible work schedules for female surgeons.

In HICs with high GGGI rankings, geographic and cultural differences affect surgeons’ perceptions and barriers. Female surgeons did more household work than male counterparts. Child-related barriers were reported more by Europeans than Americans [21,22,23,24], which was surprising given the abundance of state and hospital sponsored childcare in Europe [84]. The ubiquity of childcare in Europe may have created an environment where small gaps in childcare services are a perceived barrier, while childcare in the US is completely privatized.

Countries with extended family support systems do not face the same childcare challenges. Nigeria has lower income and low GGGI, but most Nigerian female surgeons were able to have children during residency without barriers (79%), unlike women in the US and UK (28% and 47%, respectively) [53, 61, 70]. With older relatives living in the home, Nigerian women can rely on an extended family system to run households [53, 85]. This extended family system is common in countries with similar cultural norms, allowing female surgeons from lower income and lower GGGI countries to achieve greater work–life balance at earlier stages of their careers.

Discrimination against female surgeons during their training, career, and pregnancy, was a common finding in high GGGI and higher income countries (HICs, UMICs) countries such as the US, UK and South Africa [28, 31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42, 65]. Discrimination and harassment were perpetuated most commonly by male colleagues in positions of power, which increases work-related stress and burnout while decreasing retention rates among female surgeons [33, 41]. High GGGI ranked countries may have more awareness towards discrimination against professional women. In lower ranked GGGI countries, the lack of studies on gender-based discrimination against female surgeons underrepresents the extent of the problem. A lack of awareness or minimal consequences for discrimination in low GGGI countries contributes to the absence of advocacy against discrimination. In a Turkish example, increasing the number of female surgeons in leadership is one way to reduced gender-based discrimination [29]; this model could be replicated in similar environments.

Female surgeons in HICs and high GGGI countries reported worse health outcomes compared to male surgeons and the general population. Studies from HICs reported that female surgeons had higher rates of cancer, alcohol consumption, and musculoskeletal ailment accompanied by lower life expectancies across European and North American countries [77,78,79,80]. As all the literature on female surgeons’ health focused on HICs, this finding could not be compared to female surgeons in lower income countries. But, the difference between female surgeons and the general population may be less obvious in environments where average health and lifespan standards are lower [86]. It is also possible that a career as a surgeon may provide a higher standard of living in lower income countries, which can counteract some of the health detriments from the profession seen in HICs. However, further studies would be needed to validate these hypotheses.

This study is limited by its design as a scoping review, as such there was no formal evaluation of the quality of evidence or risk of bias in the studies. Additionally, the lack of reporting from Central and South America limits this study’s generalizability to this region. The lack of studies from South or Central America likely has to do with our inclusion and exclusion criteria, specifically with regards to literature available in English. During the review many studies on South America emerged, one discussed the proportions of female surgeons in Brazil [82], but none specifically discussed the experiences of female surgeons from any country in this region. As 91% and 90% of studies exclusively examined HICs and high GGGI countries, respectively, the role of income level and GGGI ranking in female surgeons’ experiences cannot be generalized without more diversity in the literature. The lack of reporting from lower income and lower GGGI countries limits the ability to provide definitive, context-specific recommendations to improve female surgeon experiences and participation.

Conclusions

Different geographic regions along with cultural and societal norms influence gender equity and the experiences of women in surgery. Universally, women from all regions reported a lack of mentorship as a barrier to advancement. An overwhelming majority of studies originated in high-income, high GGGI countries in Europe and North America. In HICs, surgical trainee abilities are seen as equal between men and women, but women endure discrimination from male co-workers and reported more child-related barriers to their careers than their male counterparts. While female surgeon abilities were seen as inferior in some lower income countries, limited studies suggest that women may have more child rearing support and be less likely to delay childbearing. The effects of income and GGGI are complex, as neither independently predict gender equity in surgery. More studies in lower income and lower GGGI countries are needed to understand this relationship and how to improve the female surgical experience to increase surgical capacity worldwide.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- GGGI:

-

Global gender gap index

- US:

-

United States of America

- UK:

-

United Kingdom

- HIC:

-

High-income country

- UMIC:

-

Upper-middle income country

- LMIC:

-

Lower-middle income country

- LIC:

-

Low-income country

References

Wirtzfeld DA. The history of women in surgery. Can J Surg. 2009;52(4):317–20.

Colleges AoAM. Table A-7.2: applicants, first-time applicants, acceptees, and matriculants to U.S. medical schools by sex, 2010–2011 through 2019–2020. 2019.

Skinner H, Burke JR, Young AL, Adair RA, Smith AM. Gender representation in leadership roles in UK surgical societies. Int J Surg. 2019;67:32–6.

DataUSA. Physicans & surgeons. - Gender Composition DataUSA: DataUSA; 2017 cited 2019. https://datausa.io/profile/soc/291060/.

Blakemore LC, Hall JM, Biermann JS. Women in surgical residency training programs. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85(12):2477–80.

Meara JG, Greenberg SL. The Lancet Commission on Global Surgery Global surgery 2030: Evidence and solutions for achieving health, welfare and economic development. Surgery. 2015;157(5):834–5.

Organization WH. Delivered by women, led by men: A gender and equity analysis of the global health and social workforce. Human Resources for Health Observer Series No 24. 2019 (License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.).

Kilminster S, Downes J, Gough B, Murdoch-Eaton D, Roberts T. Women in medicine—is there a problem? A literature review of the changing gender composition, structures and occupational cultures in medicine. Med Educ. 2007;41(1):39–49.

Wenneras C, Wold A. Nepotism and sexism in peer-review. Nature. 1997;387(6631):341–3.

Risberg G, Johansson EE, Hamberg K. A theoretical model for analysing gender bias in medicine. Int J Equity Health. 2009;8:28.

Ly DP, Seabury SA, Jena AB. Differences in incomes of physicians in the United States by race and sex: observational study. BMJ. 2016;353:i2923.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

Group TWB. World Bank Country and Lending Groups. 2019 cited 2020. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups.

Forum WE. The Gender Gap Report 2018 World Economic Forum2018. https://reports.weforum.org/global-gender-gap-report-2018/the-global-gender-gap-index-2018/.

Ceppa DP, Dolejs SC, Boden N, Phelan S, Yost KJ, Donington J, et al. Sexual harassment and cardiothoracic surgery: #UsToo? Ann Thorac Surg. 2020;109(4):1283–8.

Wolfert C, Rohde V, Mielke D, Hernandez-Duran S. Female neurosurgeons in Europe-on a prevailing glass ceiling. World Neurosurg. 2019;129:460–6.

Steklacova A, Bradac O, de Lacy P, Benes V. E-WIN Project 2016: Evaluating the current gender situation in neurosurgery across Europe—an interactive, multiple level surgery. World Neurosurg. 2017;104:48–60.

Marks IH, Diaz A, Keem M, Ladi-Seyedian SS, Philipo GS, Munir H, et al. Barriers to women entering surgical careers: a global study into medical student perceptions. World J Surg. 2020;44(1):37–44.

Walsh DS, Gantt NL, Irish W, Sanfey HA, Stein SL. Policies and practice regarding pregnancy and maternity leave: an international survey. Am J Surg. 2019;218(4):798–802.

Wu B, Bhulani N, Jalal S, Ding J, Khosa F. Gender disparity in leadership positions of general surgical societies in North America, Europe, and Oceania. Cureus. 2019;11(12):e6285.

Cochran A, Neumayer LA, Elder WB. Barriers to careers identified by women in academic surgery: a grounded theory model. Am J Surg. 2019;218(4):780–5.

Zhuge Y, Kaufman J, Simeone DM, Chen H, Velazquez OC. Is there still a glass ceiling for women in academic surgery? Ann Surg. 2011;253(4):637–43.

Kaderli R, Guller U, Muff B, Stefenelli U, Businger A. Women in surgery: a survey in Switzerland. Arch Surg. 2010;145(11):1119–21.

Bellini MI, Graham Y, Hayes C, Zakeri R, Parks R, Papalois V. A woman’s place is in theatre: women’s perceptions and experiences of working in surgery from the Association of Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland women in surgery working group. BMJ Open. 2019;9(1):e024349.

Makama JG, Garba ES, Ameh EA. Under representation of women in surgery in Nigeria: by choice or by design? Oman Med J. 2012;27(1):66–9.

Kass RB, Souba WW, Thorndyke LE. Challenges confronting female surgical leaders: overcoming the barriers. J Surg Res. 2006;132(2):179–87.

Muchemwa FC, Erzingatsian K. Women in surgery: factors deterring women from being surgeons in Zimbabwe. East Cent Afr J Surg. 2015;19(2):5–11.

Umoetok F, Van Wyk JM, Madiba TE. Does gender impact on female doctors’ experiences in the training and practice of surgery? A single centre study. S Afr J Surg. 2017;55(3):8–12.

Eyigor H, Can IH, Incesulu A, Senol Y. Women in otolaryngology in Turkey: insight of gender equality, career development and work-life balance. Am J Otolaryngol. 2020;41(1):102305.

Yi S, Lin Y, Kansayisa G, Costas-Chavarri A. A qualitative study on perceptions of surgical careers in Rwanda: a gender-based approach. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(5):e0197290.

Oancia T, Bohm C, Carry T, Cujec B, Johnson D. The influence of gender and specialty on reporting of abusive and discriminatory behaviour by medical students, residents and physician teachers. Med Educ. 2000;34(4):250–6.

Ferris LE, Mackinnon SE, Mizgala CL, McNeill I. Do Canadian female surgeons feel discriminated against as women? CMAJ. 1996;154(1):21–7.

Park J, Minor S, Taylor RA, Vikis E, Poenaru D. Why are women deterred from general surgery training? Am J Surg. 2005;190(1):141–6.

Seemann NM, Webster F, Holden HA, Moulton CA, Baxter N, Desjardins C, et al. Women in academic surgery: why is the playing field still not level? Am J Surg. 2016;211(2):343–9.

Phillips NA, Tannan SC, Kalliainen LK. Understanding and overcoming implicit gender bias in plastic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;138(5):1111–6.

Myers SP, Hill KA, Nicholson KJ, Neal MD, Hamm ME, Switzer GE, et al. A qualitative study of gender differences in the experiences of general surgery trainees. J Surg Res. 2018;228:127–34.

Salles A, Mueller CM, Cohen GL. Exploring the relationship between stereotype perception and residents’ well-being. J Am Coll Surg. 2016a;222(1):52–8.

O’Connor MI. Medical school experiences shape women students’ interest in orthopaedic surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474(9):1967–72.

Bruce AN, Battista A, Plankey MW, Johnson LB, Marshall MB. Perceptions of gender-based discrimination during surgical training and practice. Med Educ Online. 2015;20:25923.

Saalwachter AR, Freischlag JA, Sawyer RG, Sanfey HA. The training needs and priorities of male and female surgeons and their trainees. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;201(2):199–205.

Freedman-Weiss MR, Chiu AS, Heller DR, Cutler AS, Longo WE, Ahuja N, et al. Understanding the barriers to reporting sexual harassment in surgical training. Ann Surg. 2020;271(4):608–13.

Gargiulo DA, Hyman NH, Hebert JC. Women in surgery: do we really understand the deterrents? Arch Surg. 2006;141(4):405–7.

Barnes KL, McGuire L, Dunivan G, Sussman AL, McKee R. Gender bias experiences of female surgical trainees. J Surg Educ. 2019;76(6):e1–14.

Bucknall V, Pynsent PB. Sex and the orthopaedic surgeon: a survey of patient, medical student and male orthopaedic surgeon attitudes towards female orthopaedic surgeons. Surgeon. 2009;7(2):89–95.

Hill E, Vaughan S. The only girl in the room: how paradigmatic trajectories deter female students from surgical careers. Med Educ. 2013;47(6):547–56.

Liang R, Dornan T, Nestel D. Why do women leave surgical training? A qualitative and feminist study. Lancet. 2019;393(10171):541–9.

Masud D, Undre S, Darzi A. Differences in final product of a bowel anastomosis of male and female novice surgeons. J Surg Educ. 2011;68(3):185–9.

Ali A, Subhi Y, Ringsted C, Konge L. Gender differences in the acquisition of surgical skills: a systematic review. Surg Endosc. 2015;29(11):3065–73.

Salles A, Mueller CM, Cohen GL. A values affirmation intervention to improve female residents’ surgical performance. J Grad Med Educ. 2016b;8(3):378–83.

Neumayer L, Kaiser S, Anderson K, Barney L, Curet M, Jacobs D, et al. Perceptions of women medical students and their influence on career choice. Am J Surg. 2002;183(2):146–50.

Dixon A, Silva NA, Sotayo A, Mazzola CA. Female medical student retention in neurosurgery: a multifaceted approach. World Neurosurg. 2019;122:245–51.

Yorozuya K, Kawase K, Akashi-Tanaka S, Kanbayashi C, Nomura S, Tomizawa Y. Mentorship as experienced by women surgeons in Japan. World J Surg. 2016;40(1):38–44.

Abolarinwa AA, Osuoji RI. WOMEN IN SURGERY—an overview of the evolving trends in Nigeria. J West Afr Coll Surg. 2017;7(4):1–17.

Mayer KL, Ho HS, Goodnight JE Jr. Childbearing and child care in surgery. Arch Surg. 2001;136(6):649–55.

Rangel EL, Lyu H, Haider AH, Castillo-Angeles M, Doherty GM, Smink DS. Factors associated with residency and career dissatisfaction in childbearing surgical residents. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(11):1004–11.

Turner PL, Lumpkins K, Gabre J, Lin MJ, Liu X, Terrin M. Pregnancy among women surgeons: trends over time. Arch Surg. 2012;147(5):474–9.

Troppmann KM, Palis BE, Goodnight JE Jr, Ho HS, Troppmann C. Women surgeons in the new millennium. Arch Surg. 2009;144(7):635–42.

Kolokythas A, Miloro M. Why do women choose to enter academic oral and maxillofacial surgery? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016;74(5):881–8.

Furnas HJ, Li AY, Garza RM, Johnson DJ, Bajaj AK, Kalliainen LK, et al. An analysis of differences in the number of children for female and male plastic surgeons. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;143(1):315–26.

Brown EG, Galante JM, Keller BA, Braxton J, Farmer DL. Pregnancy-related attrition in general surgery. JAMA Surg. 2014;149(9):893–7.

Mohan H, Ali O, Gokani V, McGoldrick C, Smitham P, Fitzgerald JEF, et al. Surgical trainees’ experience of pregnancy, maternity and paternity leave: a cross-sectional study. Postgrad Med J. 2019;95(1128):552–7.

Mizgala CL, Mackinnon SE, Walters BC, Ferris LE, McNeill IY, Knighton T. Women surgeons. Results of the Canadian Population Study. Ann Surg. 1993;218(1):37–46.

Fujimaki T, Shibui S, Kato Y, Matsumura A, Yamasaki M, Date I, et al. Working conditions and lifestyle of female surgeons affiliated to the Japan neurosurgical society: findings of individual and institutional surveys. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2016;56(11):704–8.

Mackinnon SE, Mizgala CL, McNeill IY, Walters BC, Ferris LE. Women surgeons: career and lifestyle comparisons among surgical subspecialties. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;95(2):321–9.

Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Satele D, Sloan J, Freischlag J. Relationship between work-home conflicts and burnout among American surgeons: a comparison by sex. Arch Surg. 2011;146(2):211–7.

Hamilton AR, Tyson MD, Braga JA, Lerner LB. Childbearing and pregnancy characteristics of female orthopaedic surgeons. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(11):e77.

Kin C, Yang R, Desai P, Mueller C, Girod S. Female trainees believe that having children will negatively impact their careers: results of a quantitative survey of trainees at an academic medical center. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):260.

Phillips EA, Nimeh T, Braga J, Lerner LB. Does a surgical career affect a woman’s childbearing and fertility? A report on pregnancy and fertility trends among female surgeons. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;219(5):944–50.

Rangel EL, Smink DS, Castillo-Angeles M, Kwakye G, Changala M, Haider AH, et al. Pregnancy and motherhood during surgical training. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(7):644–52.

Schwarz L, Sippel S, Entwistle A, Hell AK, Koenig S. Biographic characteristics and factors perceived as affecting female and male careers in academic surgery: the tenured gender battle to make it to the top. Eur Surg Res. 2016;57(3–4):139–54.

Kwong A, Chau WW, Kawase K. Work-life balance of female versus male surgeons in Hong Kong based on findings of a questionnaire designed by a Japanese surgeon. Surg Today. 2014;44(1):62–72.

Capek L, Edwards DE, Mackinnon SE. Plastic surgeons: a gender comparison. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;99(2):289–99.

Baptiste D, Fecher AM, Dolejs SC, Yoder J, Schmidt CM, Couch ME, et al. Gender differences in academic surgery, work-life balance, and satisfaction. J Surg Res. 2017;218:99–107.

Jinapriya D, Cockerill R, Trope GE. Career satisfaction and surgical practice patterns among female ophthalmologists. Can J Ophthalmol. 2003;38(5):373–8.

Kaderli R, Muff B, Stefenelli U, Businger A. Female surgeons’ mentoring experiences and success in an academic career in Switzerland. Swiss Med Wkly. 2011;141:w13233.

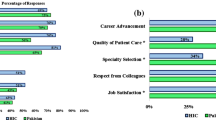

Kawase K, Carpelan-Holmstrom M, Kwong A, Sanfey H. Factors that can promote or impede the advancement of women as leaders in surgery: results from an international survey. World J Surg. 2016;40(2):258–66.

Mitura K, Koziel S, Komor K. Can the surgeon live his whole life? Analysis of the risk of death related to the profession. Pol Przegl Chir. 2018;90(1):18–24.

Rosta J, Aasland OG. Female surgeons’ alcohol use: a study of a national sample of Norwegian doctors. Alcohol Alcohol. 2005;40(5):436–40.

Chou LB, Lerner LB, Harris AH, Brandon AJ, Girod S, Butler LM. Cancer prevalence among a cross-sectional survey of female orthopedic, urology, and plastic surgeons in the United States. Womens Health Issues. 2015;25(5):476–81.

Sutton E, Irvin M, Zeigler C, Lee G, Park A. The ergonomics of women in surgery. Surg Endosc. 2014;28(4):1051–5.

Beebe KS, Krell ES, Rynecki ND, Ippolito JA. The effect of sex on orthopaedic surgeon income. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2019;101(17):e87.

Scheffer MC, Guilloux AGA, Matijasevich A, Massenburg BB, Saluja S, Alonso N. The state of the surgical workforce in Brazil. Surgery. 2017;161(2):556–61.

Colleges AAoM. Workforce Interactive Data. 2017.

Hofferth SL, Deich SG. Recent U.S. child care and family legislation in comparative perspective. J Fam Issues. 1994;15(3):424–48.

Wusu O, Isiugo-Abanihe UC. Family structure and reproductive health decision-making among the Ogu of southwestern Nigeria: a qualitative study. African Population Studies. 2003;18(2):27–45.

World Bank Country and Lending Groups. 2017. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.LE00.IN?end=2017&locations=XM-XD&start=1960&view=chart. Accessed 21 Jan 20.

Berry C, Khabele D, Johnson-Mann C, Henry-Tillman R, Joseph KA, Turner P, et al. A call to action: Black/African American women surgeon scientists, where are they? Ann Surg. 2020;272:24–9.

Chen W, Baron M, Bourne DA, Kim JS, Washington KM, De La Cruz C. A report on the representation of women in academic plastic surgery leadership. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;145(3):844–52.

Gawad N, Tran A, Martel AB, Baxter NN, Allen M, Manhas N, et al. Gender and academic promotion of Canadian general surgeons: a cross-sectional study. CMAJ Open. 2020;8(1):E34–40.

Konanur A, Egro FM, Kettering CE, Smith BT, Corcos AC, Stofman GM, et al. Gender disparities among burn surgery leadership. J Burn Care Res. 2020;41:674–80.

Bernardi K, Lyons NB, Huang L, Holihan JL, Olavarria OA, Loor MM, et al. Gender disparity among surgical peer-reviewed literature. J Surg Res. 2020;248:117–22.

Abu-Hammad S, Elsayed SA, Nourwali I, Abu-Hammad O, Sghaireen M, Abouzaid BH, et al. Influence of gender on career expectations of oral and maxillofacial surgeons. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2020.

Bernardi K, Shah P, Lyons NB, Olavarria OA, Alawadi ZM, Leal IM, et al. Perceptions on gender disparity in surgery and surgical leadership: A multicenter mixed methods study. Surgery. 2020;167(4):743–50.

Carnevale M, Phair J, Batarseh P, LaFontaine S, Koelling E, Koleilat I. Gender disparities in academic vascular surgeons. J Vasc Surg. 2020.

Smeds MR, Aulivola B. Gender disparity and sexual harassment in vascular surgery practices. J Vasc Surg. 2020.

Davids JS, Lyu HG, Hoang CM, Daniel VT, Scully RE, Xu TY, et al. Female representation and implicit gender bias at the 2017 American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons’ annual scientific and tripartite meeting. Dis Colon Rectum. 2019;62(3):357–62.

Filiberto AC, Le CB, Loftus TJ, Cooper LA, Shaw C, Sarosi GA Jr, et al. Gender differences among surgical fellowship program directors. Surgery. 2019;166(5):735–7.

Burke AB, Cheng KL, Han JT, Dillon JK, Dodson TB, Susarla SM. Is gender associated with success in academic oral and maxillofacial surgery? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2019;77(2):240–6.

Herrick-Reynolds K, Brooks D, Wind G, Jackson P, Latham K. Military Medicine and the Academic Surgery Gender Gap. Mil Med. 2019.

Tulunay-Ugur OE, Sinclair CF, Chen AY. Assessment of gender differences in perceptions of work-life integration among head and neck surgeons. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;145(5):453–8.

Brown MA, Erdman MK, Munger AM, Miller AN. Despite Growing Number of Women Surgeons, Authorship Gender Disparity in Orthopaedic Literature Persists Over 30 Years. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2019.

Harris CA, Banerjee T, Cramer M, Manz S, Ward ST, Dimick J, et al. Editorial (Spring) Board? Gender composition in high-impact general surgery journals over 20 years. Ann Surg. 2019;269(3):582–8.

Lyons NB, Bernardi K, Huang L, Holihan JL, Cherla D, Martin AC, et al. Gender disparity in surgery: an evaluation of surgical societies. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2019;20(5):406–10.

Dumitra TC, Alam R, Fiore JF Jr., Mata J, Fried GM, Vassiliou MC, et al. Is there a gender bias in the advancement to SAGES leadership? Surg Endosc. 2019.

Smith BT, Egro FM, Murphy CP, Stavros AG, Kenny EM, Nguyen VT. Change is happening: an evaluation of gender disparities in academic plastic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;144(4):1001–9.

Dossani RH, Terrell D, Kosty JA, Ross RC, Demand A, Wild E, et al. Gender disparities in academic rank achievement in neurosurgery: a critical assessment. J Neurosurg. 2019;8:1–6.

Zhang B, Westfal ML, Griggs CL, Hung YC, Chang DC, Kelleher CM. Practice patterns and work environments that influence gender inequality among academic surgeons. Am J Surg. 2019.

Fassiotto M, Li J, Maldonado Y, Kothary N. Female surgeons as counter stereotype: the impact of gender perceptions on trainee evaluations of physician faculty. J Surg Educ. 2018;75(5):1140–8.

Hirayama M, Fernando S. Organisational barriers to and facilitators for female surgeons’ career progression: a systematic review. J R Soc Med. 2018;111(9):324–34.

Epstein NE. Discrimination against female surgeons is still alive: where are the full professorships and chairs of departments? Surg Neurol Int. 2017;8:93.

Furnas HJ, Garza RM, Li AY, Johnson DJ, Bajaj AK, Kalliainen LK, et al. Gender differences in the professional and personal lives of plastic surgeons. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;142(1):252–64.

Amoli MA, Flynn JM, Edmonds EW, Glotzbecker MP, Kelly DM, Sawyer JR. Gender differences in pediatric orthopaedics: what are the implications for the future workforce? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474(9):1973–8.

Webster F, Rice K, Christian J, Seemann N, Baxter N, Moulton CA, et al. The erasure of gender in academic surgery: a qualitative study. Am J Surg. 2016;212(4):559–65.

Sanfey H, Fromson J, Mellinger J, Rakinic J, Williams M, Williams B. Surgeons in difficulty: an exploration of differences in assistance-seeking behaviors between male and female surgeons. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;221(2):621–7.

Okoshi K, Nomura K, Fukami K, Tomizawa Y, Kobayashi K, Kinoshita K, et al. Gender inequality in career advancement for females in Japanese academic surgery. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2014;234(3):221–7.

Cochran A, Hauschild T, Elder WB, Neumayer LA, Brasel KJ, Crandall ML. Perceived gender-based barriers to careers in academic surgery. Am J Surg. 2013;206(2):263–8.

Hebbard PC, Wirtzfeld DA. Practice patterns and career satisfaction of Canadian female general surgeons. Am J Surg. 2009;197(6):721–7.

Schroen AT, Brownstein MR, Sheldon GF. Women in academic general surgery. Acad Med. 2004;79(4):310–8.

End A, Mittlboeck M, Piza-Katzer H. Professional satisfaction of women in surgery: results of a national study. Arch Surg. 2004;139(11):1208–14.

Roberts SR, Kells AF, Cosgrove DM 3rd. Collective contributions of women to cardiothoracic surgery: a perspective review. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;71(2 Suppl):S19-21.

Colletti LM, Mulholland MW, Sonnad SS. Perceived obstacles to career success for women in academic surgery. Arch Surg. 2000;135(8):972–7.

Risser MJ, Laskin DM. Women in oral and maxillofacial surgery: factors affecting career choices, attitudes, and practice characteristics. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1996;54(6):753–7.

Klifto KM, Payne RM, Siotos C, Lifchez SD, Cooney DS, Broderick KP, et al. Women continue to be underrepresented in surgery: a study of AMA and ACGME data from 2000 to 2016. J Surg Educ. 2020;77(2):362–8.

Beasley SW, Khor SL, Boakes C, Jenkins D. Paradox of meritocracy in surgical selection, and of variation in the attractiveness of individual specialties: to what extent are women still disadvantaged? ANZ J Surg. 2019;89(3):171–5.

Gong D, Winn BJ, Beal CJ, Blomquist PH, Chen RW, Culican SM, et al. Gender differences in case volume among ophthalmology residents. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2019;137:1015–20.

Gerull KM, Loe M, Seiler K, McAllister J, Salles A. Assessing gender bias in qualitative evaluations of surgical residents. Am J Surg. 2019;217(2):306–13.

Lebares CC, Braun HJ, Guvva EV, Epel ES, Hecht FM. Burnout and gender in surgical training: a call to re-evaluate coping and dysfunction. Am J Surg. 2018;216(4):800–4.

Fitzgerald JE, Tang SW, Ravindra P, Maxwell-Armstrong CA. Gender-related perceptions of careers in surgery among new medical graduates: results of a cross-sectional study. Am J Surg. 2013;206(1):112–9.

Davis EC, Risucci DA, Blair PG, Sachdeva AK. Women in surgery residency programs: evolving trends from a national perspective. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212(3):320–6.

Benson S, Sammour T, Neuhaus SJ, Findlay B, Hill AG. Burnout in Australasian Younger Fellows. ANZ J Surg. 2009;79(9):590–7.

Williams C, Cantillon P. A surgical career? The views of junior women doctors. Med Educ. 2000;34(8):602–7.

Bingmer K, Walsh DS, Gantt NL, Sanfey HA, Stein SL. Surgeon experience with parental leave policies varies based on practice setting. World J Surg. 2020.

Carter JV, Polk HC Jr, Galbraith NJ, McMasters KM, Cheadle WG, Poole M, et al. Women in surgery: a longer term follow-up. Am J Surg. 2018;216(2):189–93.

Rangel EL, Castillo-Angeles M, Changala M, Haider AH, Doherty GM, Smink DS. Perspectives of pregnancy and motherhood among general surgery residents: a qualitative analysis. Am J Surg. 2018;216(4):754–9.

Radunz S, Hoyer DP, Kaiser GM, Paul A, Schulze M. Career intentions of female surgeons in German liver transplant centers considering family and lifestyle priorities. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2017;402(1):143–8.

Okoshi K, Nomura K, Taka F, Fukami K, Tomizawa Y, Kinoshita K, et al. Suturing the gender gap: Income, marriage, and parenthood among Japanese Surgeons. Surgery. 2016;159(5):1249–59.

Hill E, Solomon Y, Dornan T, Stalmeijer R. “You become a man in a man’s world”: is there discursive space for women in surgery? Med Educ. 2015;49(12):1207–18.

Chan S, Cheung P, Lee J, Fung J, Patil N, Kwok S, Lam S. Women surgeons in Hong Kong. Surg Pract. 2010;14(1):2–7.

Ahmadiyeh N, Cho NL, Kellogg KC, Lipsitz SR, Moore FD Jr, Ashley SW, et al. Career satisfaction of women in surgery: perceptions, factors, and strategies. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210(1):23–8.

Rogers AC, Wren SM, McNamara DA. Gender and specialty influences on personal and professional life among trainees. Ann Surg. 2019;269(2):383–7.

Grandis JR, Gooding WE, Zamboni BA, Wagener MM, Drenning SD, Miller L, et al. The gender gap in a surgical subspecialty: analysis of career and lifestyle factors. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130(6):695–702.

Frank E, Brownstein M, Ephgrave K, Neumayer L. Characteristics of women surgeons in the United States. Am J Surg. 1998;176(3):244–50.

Sangji NF, Fuentes E, Donelan K, Cropano C, King D. Gender Disparity in trauma surgery: compensation, practice patterns, personal life, and wellness. J Surg Res. 2020;250:179–87.

Maxwell JH, Randall JA, Dermody SM, Hussaini AS, Rao H, Nathan AS, et al. Gender and compensation among surgical specialties in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Surg. 2020.

Buerba RA, Arshi A, Greenberg DC, SooHoo NF. The Role of Gender, academic affiliation, and subspecialty in relation to industry payments to orthopaedic surgeons. J Natl Med Assoc. 2020;112(1):82–90.

Forrester LA, Seo LJ, Gonzalez LJ, Zhao C, Friedlander S, Chu A. Men receive three times more industry payments than women academic orthopaedic surgeons, even after controlling for confounding variables. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2020;478:1.

Padmanaban V, Tran A, Johnston PF, Gore A, Beebe KS, Kunac A, et al. Gender equity in humanitarian surgical outreach: a decade of volunteer surgeons. J Surg Res. 2019;244:343–7.

Oslock WM, Paredes AZ, Baselice HE, Rushing AP, Ingraham AM, Collins C, et al. Women surgeons and the emergence of acute care surgery programs. Am J Surg. 2019;218(4):803–8.

Dossa F, Simpson AN, Sutradhar R, Urbach DR, Tomlinson G, Detsky AS, et al. Sex-based disparities in the hourly earnings of surgeons in the fee-for-service system in Ontario, Canada. JAMA Surg. 2019;154:1134–42.

Whitaker M. The surgical personality: does it exist? Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2018;100(1):72–7.

Neuhaus SJ. The ties that bind: what’s in a title? ANZ J Surg. 2018;88(3):136–9.

Morris M, Chen H, Heslin MJ, Krontiras H. A structured compensation plan improves but does not erase the sex pay gap in surgery. Ann Surg. 2018;268(3):442–8.

Weiss A, Parina R, Tapia VJ, Sood D, Lee KC, Horgan S, et al. Assessing the domino effect: female physician industry payments fall short, parallel gender inequalities in medicine. Am J Surg. 2018;216(4):723–9.

Holliday EB, Brady C, Pipkin WC, Somerson JS. Equal pay for equal work: Medicare procedure volume and reimbursement for male and female surgeons performing total knee and total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018;100(4):e21.

Frohman HA, Nguyen TH, Co F, Rosemurgy AS, Ross SB. The non-white woman surgeon: a rare species. J Surg Educ. 2015;72(6):1266–71.

Dusch MN, Braun HJ, O’Sullivan PS, Ascher NL. Perceptions of surgeons: what characteristics do women surgeons prefer in a colleague? Am J Surg. 2014;208(4):601–4.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Shea E. Gilliam M.S., for her assistance with visualization of global gender gap indices and publication data.

Funding

No funding was used.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MX collected the articles, analyzed the abstracts and full-text articles for the review, and drafted the manuscript. NM contributed to the conception of the research, analyzed the abstracts and full-text articles and drafted the manuscript. AS, WM, and CY all substantively revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1

. PRIMSA-ScR-Checklist.

Additional file 2

. Scoping Review Protocol.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Xepoleas, M.D., Munabi, N.C.O., Auslander, A. et al. The experiences of female surgeons around the world: a scoping review. Hum Resour Health 18, 80 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-020-00526-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-020-00526-3