Abstract

Background

Schwannomas of the colon and rectum are rare among gastrointestinal schwannomas. They are usually discovered incidentally as a submucosal mass on routine colonoscopy and diagnosed on pathologic examination of the operative specimen. Little information exists on the diagnosis and management of this rare entity.

The aim of this study is to report a case of cecal schwannoma and the results of a systematic review of colorectal schwannoma in the literature.

Main body

PubMed, Scopus, and Cochrane database searches were performed for case reports and case series of colonic and rectal schwannoma.

Ninety-five patients with colonic or rectal schwannoma from 70 articles were included. Median age was 61.5 years (59% female). Presentation was asymptomatic (28%), rectorrhagia (23.2%), or abdominal pain (15.8%). Schwannoma occurred in the left and sigmoid colon in 36.8%, in the cecum and right colon in 30.5%, and in the rectum in 21.1%. Median tumor size was 3 cm and 56.2% of patients who underwent preoperative colonoscopy had a typical smooth submucosal mass. At pathology, 97.9, 13.7, and 5.3% of schwannomas stained positive for S100, vimentin, and GFAP, respectively. The median mitotic index was 1/50.

Conclusions

Colorectal schwannoma is a very rare subtype of gastrointestinal schwannoma which occurs in the elderly, almost equally in men and women. Schwannoma should be included in the differential diagnosis of a submucosal lesion along with gastrointestinal stromal tumor, neuro-endocrine tumors, and leiomyoma-leiomyosarcoma. Definitive diagnosis is based on immunohistochemistry of the operative specimen. Rarely malignant, surgery is the mainstay of treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Schwannomas of the gastrointestinal tract are spindle cell tumors originating from peripheral nerve lining Schwann cells and represent a very rare entity, accounting for approximately 2–6% of all mesenchymal tumors [1, 2]. In fact, the differential diagnosis of this entity includes all mesenchymal or neuro-ectodermal neoplasms, in decreasing frequency: gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs), leiomyomas, leiomyosarcomas, neurofibromas, ganglioneuromas, paragangliomas, lipomas, granular cell tumors, and glomus tumors [3]. Gastrointestinal tract schwannomas occur in decreasing frequency in the stomach (83%), small bowel (12%), and, finally, the colon and rectum [1]. Gastrointestinal schwannomas occur at similar rates in men and women with a mean age of 60–65 years [3]. Most commonly, schwannoma is discovered incidentally on screening endoscopy or during abdominal imaging that is being done for another reason, and the diagnosis is made on definitive pathologic examination of operative specimen [4]. On immunohistology, they stain positive for S100. Gastrointestinal schwannomas occur indifferently in men and women with a mean age of 60–65 years [3]. Rectal schwannoma may cause symptoms such as obstruction, bleeding, and tenesmus. Few data exist on this rare entity in the literature.

The aim of this study is to report an incidental finding cecal schwannoma with a systematic literature review of colorectal schwannoma, to describe the clinical, diagnostic (endoscopic, abdominal imaging), pathologic, and prognostic features of colorectal schwannomas.

Materials and methods

We performed a systematic review of the literature using three databases (PubMed, Scopus, and Cochrane). In the PubMed search, we used the following search terms: (“Colorectal Neoplasms”[Mesh]) AND “Neurilemmoma”[Mesh] with filter for case reports and (“Colorectal Neoplasms”[Mesh]) AND “Neurilemmoma”[Mesh] AND case series. Free terms included (colorectal OR rectum OR rectal OR colon OR colonic) AND Schwannoma and (colorectal OR rectum OR rectal OR colon OR colonic) AND Schwannoma AND case series. In the Scopus database search, we used the terms (TITLE-ABS-KEY ({case report})) AND (TITLE-ABS-KEY(schwannoma) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(colorectal OR rectum OR rectal OR colon OR colonic)) OR ((TITLE-ABS-KEY(schwannoma) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(colorectal OR rectum OR rectal OR colon OR colonic)) AND ({case series})). In the Cochrane search, we used the following: Title-abstract-keywords: Schwannoma and Title-abstract-keywords: Neurilemmoma. The search strategy had no publication date, or publication type restriction. In addition, the reference lists of relevant reviews or included articles were also searched to find other eligible studies. We included only studies published in English.

Study characteristics such as patient age, sex, and presenting symptoms, diagnostic exams, tumor characteristics (size, location, appearance on colonoscopy and on imaging), timing of diagnosis (endoscopic biopsy or post-operatively), type of resection (endoscopic, transanal, laparoscopic, and open), tumor immunostaining (S100, vimentin, glial fibrillary acidic protein [GFAP], Ki67), and mitotic rate reported in the pathology report, lymph node status, and the degree of aggressiveness of the tumor were evaluated in the literature review.

Results

Case report

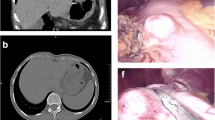

An asymptomatic 70-year-old female known to have surgically treated squamous cell carcinoma of the nose underwent a routine screening colonoscopy that revealed an uncomplicated diverticulosis and a cecal submucosal mass (Fig. 1). The appearance was most likely correlated with a submucosal tumor and less likely to be an extrinsic compression. At pathology, colonoscopic biopsies of the mass showed normal colonic mucosa. Laboratory examination showed no anemia (hb 13.2 g/dL) was negative for CEA tumor marker (CEA 2.2 μg/L). Abdominal computed tomography scan (CT scan) revealed a well-circumscribed hypervascular anterior cecal wall mass (Fig. 2) with no liver metastases and no other distant lesions. The mass had no metabolic activity on either FDG-PET scan or on Octreo-PET (Fig. 3a, b).

After multidisciplinary team discussion, a differential diagnosis of mesenchymal tumor of the colon (GIST, leiomyoma, and leiomyosarcoma) was suggested and we decided to perform an exploratory surgery. The patient was consented for open exploration by mini-laparotomy and possible right hemi-colectomy. The right colon was mobilized at the white line of Toldt, the 3 cm white cecal mass was well circumscribed, and a wedge resection, including the appendix, using GIA 75 (Ethicon Endo-Surgery GIA; 75 mm; Guaynabo, Puerto Rico 00969 USA) was performed. The operative specimen was sent for frozen section at pathology. The temporary diagnosis was a benign spindle cell tumor. The intra-operative decision was to wait for the definitive histopathologic examination report in order to try to avoid a right hemicolectomy. The final pathology report revealed a benign spindle cell tumor that stained negative for CD117 and DOG-1 and was diagnosed as cecal schwannoma with a reactive lymph node (Fig. 4).

The post-operative course was uneventful and the patient started oral feeding the same night and was discharged on day 5 with pain killers. The final multidisciplinary committee decision was follow-up without further treatment needed. At 1-year follow-up, the patient is disease free.

Systematic literature review

Study selection

A total of 521 articles were identified from the PubMed, Scopus, and Cochrane databases. After removing duplicated articles, 230 articles remained for further assessment. A total of 171 articles were excluded on the basis of the titles and the abstracts. Of the remaining 120 articles, only 78 articles had full text published in English. After full text review of these remaining articles, 70 were eligible and included in the systematic review (Fig. 5).

Patient and tumor characteristics

A total of 70 articles (Table 1) reporting 95 cases of colorectal schwannoma were found, including one article reporting a series of 20 colorectal schwannomas from the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology [4]. A total of 96 patients were reviewed, including our case [1, 2, 4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71]. The statistical analysis of all patient characteristics is listed in Table 2.

There were 40 male (41.7%) and 56 female (58.3%) patients with a mean age of 61.2 years (range 14 to 95 years). Thirty-five patients (36.4%) were asymptomatic at presentation, including eight with positive fecal occult blood test (8.3%). The most common presenting symptoms were rectorrhagia (22.9%) followed by nonspecific abdominal pain (15.6%), constipation (7.3%), tenesmus (7.3%), and increased abdominal girth (2.1%).

Schwannoma occurred most frequently in the cecum and right colon (30.5%) followed by the sigmoid (28.1%), the rectum (21.1%), the left colon (8.3%), the transverse colon (5.3%), and the appendix (1.1%). The tumor size ranged from 0.3 to 28 cm with a mean of 3.78 cm (median 3 cm).

On colonoscopy, results were available in 73 out of 96 patients (76%). Schwannoma had the typical submucosal mass appearance with smooth mucosal surface in 41 (56.2%) and with ulcerated mucosa in 5 (6.8%). Fifteen patients (20.5%) had a tumor described as submucosal polyp, and nine patient tumors (12.3%) were described as a mass, either fungating (8.2%) or polypoid (4.1%).

Pre-operative tumor imaging results were available for 46 patients (48%). The most common imaging done was abdominal CT scan (35 patients, 76%). In the majority, the CT scan report lacked a description of the schwannoma and identified a colorectal mass. In 12 cases (34.3%), the schwannoma was described as a well-circumscribed homogenous lesion with low enhancement on arterial phase and in one case as a well-circumscribed homogenous lesion without arterial phase enhancement. Endorectal ultrasound (EUS) results were available for only seven patients (7.3%) and all of these showed a transmural hypo-echogenic mass. FDG-PET/CT scan was done in only four patients (including our patient) and showed a hypermetabolic lesion in three of them.

The diagnosis of schwannoma was made on the operative specimen in the majority of patients (74%), on endoscopic or transanal biopsy in 23 patients (24%), and diagnostic method was not reported in 2% of cases.

All patients with no biopsy or inconclusive biopsies underwent radical colonic resection either open (60.4%) or laparoscopic (11.5%). Three patients were diagnosed with schwannoma pre-operatively and underwent wedge colonic resection. Fifteen patients had colonoscopic resection at their initial examination and resection was judged sufficient and they did not undergo further treatment. Transanal surgery was performed in seven patients with rectal schwannomas including two treated by transanal microsurgery.

On pathologic examination, the Antonini subtype was available or deduced in 26 out of 96 patients, 57.7% were type A (14 patients), half of the remaining were type B, and the other half were both types A and B. In all available immuno-histologic examinations, schwannomas stained positive for S100 in 97.9%, for vimentin in 13.5%, for glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) in 5.2%, for CD34 in 2.1%, and for CD68 in 1%. Tumor mitotic activity results were reported in only 41 patients (Ki-67 in 5 patients (5.3%) the highest below 5%, MIB-1 in 6 patients (6.3%) the highest < 5%, and low mitotic count in 30 (31.6%) with a mean of 2.1/50 and a median of 1/50 high-power fields). Lymph node status was available in only 11 pathology reports (11.5%) and was negative in all of these. Schwannoma was judged to be benign in 93 out 95 patients (96.9%), and local and hepatic pattern recurrences were observed in 3 patients (3.1%) and were reported as “malignant” schwannomas [67, 69, 71].

Discussion

Schwannomas are extremely rare tumors of the nerve sheath, developing from Schwann cells. In the gastrointestinal tract, they present as spindle cell tumors, originating from Auerbach’s myenteric plexus rather than Meissner’s submucosal plexus, and account for approximately 2–6% of all mesenchymal tumors [1].

Colorectal schwannoma is a very rare neoplasm and is the least frequent location for a GI schwannoma [1, 2]. Based on our systematic review, colorectal schwannoma occurs slightly more in female patients (59%), with a mean age of 61.5 years, and a wide age range from 14 to 95 years. Schwannoma is frequently diagnosed as a submucosal mass or polyp [4, 10, 28, 30, 31, 33, 39, 41,42,43, 46,47,48,49, 66] with a smooth surface but in rare cases can ulcerate into the mucosa [1, 2, 16, 18, 23, 29, 40]. This submucosal mass is usually discovered incidentally during routine screening colonoscopy. As is true for all other mesenchymal tumors, mucosal biopsy is usually inconclusive. Deep biopsy or submucosal resection [4, 18, 22, 26, 31, 41, 43, 46,47,48, 50, 57] can help differentiate schwannoma from other mesenchymal tumors such as gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST), neuro-endocrine tumors (NET), leiomyomas, and leiomyoma-sarcomas, or from adenocarcinomas in cases where the mucosa is ulcerated. In decreasing frequency, schwannoma occurs in the right colon and cecum, followed by the sigmoid colon, the rectum, the left colon, and, finally, the transverse colon. The size of schwannomas ranges from less than 1 cm lesions to very large tumors up to 28 cm that present with an increase in abdominal girth [67, 68].

For differential diagnosis of schwannoma, abdominal CT scan can help differentiate between schwannoma and other mesenchymal tumors. Schwannomas appear as well-defined homogenous mural masses with low enhancement [1, 5, 7, 10, 11, 14, 35, 36, 40, 51, 70] in comparison with the heterogenous aspect of GIST and the ill-defined aspect of adenocarcinomas [72]. Less than half of the published case reports had a CT scan done, approximately half of these had endoluminal resection and did not require abdominal imaging. In two thirds of patients who underwent CT scan, the published case reports lacked a description of the colorectal mass scan and did not specify the characteristics of the mass with regard to shape and arterial enhancement, factors which might be helpful for differential diagnosis. Echo-endoscopic ultrasonography can also be useful for diagnosis as schwannoma appears as a well-defined transmural hypoechoic mass.

In this review, four patients (4.16%) underwent metabolic imaging (FDG-PET/CT scan). Schwannoma exhibited hypermetabolic activity in three of these (75%) and no metabolic activity in one of them (25%). In the majority of cases, FDG-PET/CT scan was performed in the preoperative work-up of an atypical colorectal mass to differentiate between a malignant and a benign lesion, as in our case report. In patients with and without metabolic activity, all lesions were reported as benign. Although reported data are limited, current data do not suggest a role for FDG-PET/CT scan to differentiate between benign and malignant gastrointestinal schwannoma. In addition, octreotide receptor PET/CT scan can help to exclude the diagnosis of NET, as in the present report.

The definitive diagnosis is made on immunohistopathologic examination of the operative specimen. Macroscopically, schwannomas tend to be lobulated well-defined tumors ulcerating into the mucosa [73]. Furthermore, they stain positive for S100, and occasionally for vimentin, and stain negative for SMA, Desmin, CD117, and P53 [74]. One of the malignant schwannomas [71] had a c-kit mutation along with S100 which makes a diagnosis of GIST more likely, although the tumor was considered to be a malignant schwannoma.

Two histological growth patterns have been described: Antoni A, characterized by the dense growth of fusiform cells compactly arranged in palisades to form Verocay bodies and Antoni B in which the fusiform cells are more loosely distributed with rounded or elongated nuclei, with a great quantity of myxoid stroma and xanthomatous histiocytes. Recognition of these patterns has proved useful in the histologic identification of schwannomas [2].

Colorectal schwannomas are reported as benign in more than 98% of cases. They are characterized by a low rate of mitosis, the absence of atypical mitotic figures, and nuclear hyperpigmentation. The degree of aggressiveness depends on the Ki-67 index and the mitotic index. Ki-67 index is recommended as an indicator of malignancy. A value of more than 5% correlates with greater tumor aggressiveness and a value of more than 10% is considered malignant [2]. A higher risk of metastasis and/or recurrence has been associated with a mitotic activity rate > 5 mitoses per field at high magnification and a tumor size larger than 5 cm [8]. More than half of the published case reports lacked the complete pathologic description of the schwannoma, and the differentiation between benign and malignant was not based on mitotic index, Ki-67, or MIB-1. Malignant profile was judged based on long-term local and distal recurrence [67, 69, 71]. Metastatic spreading in lymph nodes is exceptional but Das Gupta and Brasfield have reported the occurrence of loco-regional metastases in aggressive tumors (2%) [9]. Three cases of malignant colorectal schwannoma were reported [67, 69, 71] but they lacked data on mitotic activity, Ki-67, and MIB-1. In these case reports, the authors made their conclusion depending on the large size with numerous mitoses [67] and on the emergence of long-term local recurrence and liver metastasis [69,70,71].

The best therapeutic option is complete surgical resection with free negative margins. Radical surgery is not necessary. In reported cases, the observed high frequency of radical resection is due to the absence of accurate preoperative diagnosis. When diagnosed preoperatively, schwannomas were resected either endoscopically or by a wedge resection [35, 56]. According to our research, no patients were offered adjuvant radiotherapy or chemotherapy.

Our review was limited by the small number of published case reports and the low index of pre-operative suspicion which resulted in somewhat hazardous diagnostic examinations. Most patients either did not undergo an abdominal imaging modality or lacked a detailed description of imaging results. Moreover, mitotic index was not calculated in all patients.

Conclusions

In conclusion, schwannoma of the gastrointestinal tract is a rare, usually benign, tumor, and colonic schwannoma is an even more rare occurrence. Differential diagnosis of a submucosal lesion should include schwannoma as well as GIST, NET, and leiomyoma-leiomyosarcoma. Submucosal or deep biopsy might help to make a pre-operative diagnosis. Contrast-enhanced CT scan with low enhancement could help differentiate the well-defined schwannoma from other mesenchymal tumors or adenocarcinoma and exclude distant metastasis in cases of other diagnoses. The definitive diagnosis is based on immunohistochemistry of the operative specimen. Schwannoma stains strongly for S100, and the mitotic index should be calculated to help differentiate benign from malignant lesions. Surgery is the mainstay of treatment, and as for other mesenchymal tumors, wedge resection rather than classic regional resection is advised.

Abbreviations

- CEA:

-

Carcinoembryonic antigen

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- EUS:

-

Endorectal ultrasound

- FDG-PET:

-

Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography

- GFAP:

-

Glial fibrillary acidic protein

- GI:

-

Gastrointestinal

- GIST:

-

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor

- NET:

-

Neuroendocrine tumor

References

Tsunoda C, Kato H, Sakamoto T, Yamada R, Mitsumaru A, Yokomizo H, et al. A case of benign schwannoma of the transverse colon with granulation tissue. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2009;3:116–20. https://doi.org/10.1159/000214837.

Nonose R, Lahan AY, Santos Valenciano J, Martinez CA. Schwannoma of the colon. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2009;3:293–9. https://doi.org/10.1159/000237736.

Daimaru Y, Kido H, Hashimoto H, Enjoji M. Benign schwannoma of the gastrointestinal tract: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study. Hum Pathol. 1988;19:257–64.

Miettinen M, Shekitka KM, Sobin LH. Schwannomas in the colon and rectum: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 20 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:846–55. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000478-200107000-00002.

Barbeiro S, Martins C, Gonçalves C, Arroja B, Canhoto M, Silva F, et al. Schwannoma—a rare subepithelial lesion of the colon. GE Port J Gastroenterol. 2015;22:70–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpge.2015.01.006.

Jung EJ, Han HS, Koh YC, Cho J, Ryu CG, Paik JH, et al. Metachronous schwannoma in the colon with vestibular schwannoma. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2014;87:161–5. https://doi.org/10.4174/astr.2014.87.3.161.

Park KJ, Kim KH, Roh YH, Kim SH, Lee JH, Rha SH, et al. Isolated primary schwannoma arising on the colon: report of two cases and review of the literature. J Korean Surg Soc. 2011;80:367–72. https://doi.org/10.4174/jkss.2011.80.5.367.

Hornick JL, Bundock EA, Fletcher CDM. Hybrid schwannoma/perineurioma: clinicopathologic analysis of 42 distinctive benign nerve sheath tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1554–61. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181accc6c.

Akgul E, Inal M, Soyupak SK, et al. Benign rectal schwannoma. Eur J Radiol Extra. 2003;45:67–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1571-4675(03)00007-5.

Wang WB, Chen WB, Lin JJ, Xu JH, Wang JH, Sheng QS. Schwannoma of the colon: a case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2016;11:2580–2. https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2016.4271.

Tashiro Y, Matsumoto F, Iwama K, Shimazu A, Matsumori S, Nohara S, et al. Laparoscopic resection of schwannoma of the ascending colon. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2015;9:15–9. https://doi.org/10.1159/000373882.

Suzuki T, Suwa K, Hada T, Okamoto T, Fujita T, Yanaga K. Local excision of rectal schwannoma using transanal endoscopic microsurgery: a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2014;5:1193–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijscr.2014.11.020.

Bugiantella W, Rondelli F, Mariani L, Peppoloni L, Cristallini E, Mariani E. Schwannoma of the colon: a case report. Oncol Lett. 2014;8:2511–2. https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2014.2545.

De Mesquita Neto JB, Lima Verde Leal RM, De Brito EV, Cordeiro DF, Costa ML. Solitary schwannoma of the cecum: case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Oncol. 2013;6:62–5. https://doi.org/10.1159/000346785.

Vasilakaki T, Skafida E, Arkoumani E, Grammatoglou X, Tsavari KK, Myoteri D, et al. Synchronous primary adenocarcinoma and ancient schwannoma in the colon: an unusual case report. Case Rep Oncol. 2012;5:164–8. https://doi.org/10.1159/000337689.

Kanneganti K, Patel H, Niazi M, Kumbum K, Balar B. Cecal schwannoma: a rare cause of gastrointestinal bleeding in a young woman with review of literature. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2011:142781. https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/142781.

Goh BKP, Chow PKH, Kesavan S, Yap WM, Ong HS, Song IC, et al. Intraabdominal schwannomas: a single institution experience. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:756–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-007-0441-3.

Inagawa S, Hori M, Shimazaki J, Matsumoto S, Ishii H, Itabashi M, et al. Solitary schwannoma of the colon: report of two cases. Surg Today. 2001;31:833–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s005950170060.

Turaihi H, Assam JH, Sorrell M. Ascending colon schwannoma an unusual cause of acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding. S D Med. 2017;70:33–7. PMID: 28810100

Uhr A, Singh AP, Munoz J, Aka A, Sion M, Jiang W, et al. Colonic schwannoma: a case study and literature review of a rare entity and diagnostic dilemma. Am Surg. 2016;82:1183–6. PMID: 28234182

Meeks MW, Grace S, Chen Y, Petterchak J, Bolesta E, Zhou Y, et al. Synchronous quadruple primary neoplasms: colon adenocarcinoma, collision tumor of neuroendocrine tumor and Schwann cell hamartoma and sessile serrated adenoma of the appendix. Anticancer Res. 2016;36:4307–11. PMID: 27466549

Terada T. Schwannoma and leiomyoma of the colon in a patient with ulcerative colitis. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2016;47:328–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12029-015-9747-7.

Çakır T, Aslaner A, Yaz M, Ur G. Schwannoma of the sigmoid colon. BMJ Case Rep. 2015; https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2014-208934.

Dickson-Lowe RA, James CL, Bailey CM, Abdulaal Y. Caecal schwannoma: a rare cause of per rectal bleeding in a 72-year-old man. BMJ Case Rep. 2014; https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2014-205643.

Tokuhara K, Nakatani K, Oishi M, Iwamoto S, Inoue K, Kwon AH. Laparoscopic reduced port surgery for schwannoma of the sigmoid colon: a case report. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2014;7:260–3. https://doi.org/10.1111/ases.12102.

Baskaran V, Cho WS, Perry M. Rectal schwannoma on endoscopic polypectomy. BMJ Case Rep. 2014; https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2013-010483.

Verdú-Fernández MÁ, Guillén-Paredes MP, García-García ML, García-Marín JA, Pellicer-Franco E, Aguayo-Albasini JL. Schwannoma in descending colon: presentation of a neoplasm in a rare location. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2013;105:502–3. PMID: 24274453

Baek SJ, Hwangbo W, Kim J, Kim IS. A case of benign schwannoma of the ascending colon treated with laparoscopic-assisted wedge resection. Int Surg. 2013;98:315–8. https://doi.org/10.9738/INTSURG-D-13-00015.1.

Petrie BA, Ho JM, Tolan AM. Schwannoma of the sigmoid colon: a rare cause of sigmoidorectal intussusception. ANZ J Surg. 2014;84:990–1. https://doi.org/10.1111/ans.12364.

Shelat VG, Li K, Naik S, Ng CY, Rao N, Rao J, et al. Abdominal schwannomas: case report with literature review. Int Surg. 2013;98:214–8. https://doi.org/10.9738/INTSURG-D-13-00019.1.

Trivedi A, Ligato S. Microcystic/reticular schwannoma of the proximal sigmoid colon: case report with review of literature. Arch Pathol Lab. 2013;137:284–8. https://doi.org/10.5858/arpa.2011-0386-CR.

Kawaguchi S, Yamamoto R, Yamamura M, Oyamada J, Sato H, Fuke H, et al. Plexiform schwannoma of the rectum. Dig Endosc. 2014;26:113–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/den.12022.

Tan AC, Tan CH, Ng CY. Multimodality imaging features of rectal schwannoma. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2012;41:476–8. PMID: 23138147

Yang X, Zeng Y, Wang J. Hybrid schwannoma/perineurioma: report of 10 Chinese cases supporting a distinctive entity. Int J Surg Pathol. 2013;21:22–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/1066896912454566.

Matsumoto T, Yamamoto S, Fujita S, Akasu T, Moriya Y. Cecal schwannoma with laparoscopic wedge resection: report of a case. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2011;4:178–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1758-5910.2011.00089.x.

Kim HJ, Kim CH, Lim SW, Huh JW, Kim YJ, Kim HR. Schwannoma of ascending colon treated by laparoscopic right hemicolectomy. World J Surg Oncol. 2012;10:81. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7819-10-81.

Vijayasekaran A, Tsikitis VL, Gardetto JS, Bracamonte ER, Cohen AM. Rectal schwannoma (neurilemmoma). Am Surg. 2012;78:84–5. PMID: 22369805

Wu YC, Hsieh TC, Kao CH, Yen KY, Sun SS. Simultaneous rectal schwannoma and prostatic adenocarcinoma detected on FDG PET/CT. Clin Nucl Med. 2011;36:948–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/RLU.0b013e31821a2864.

Tedeschi M, Cuccia F, Angarano E, Piscitelli D, Gigante G, Altomare DF. Solitary schwannoma of the rectum mimicking rectal cancer. Report of a case and review of the literature. Ann Ital Chir. 2011;82:309–12. PMID: 21834483

Tanaka T, Ishihara Y, Takabayashi N, Kobayashi R, Hiramatsu T, Kuriki K. Gastrointestinal: asymptomatic colonic schwannoma in an elderly woman; a rare case. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:1339. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06677.x.

Rocco EG, Iannuzzi F, Dell'Era A, Falleni M, Moneghini L, Di Nuovo F, et al. Schwann cell hamartoma: case report. BMC Gastroenterol. 2011;11:68. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-230X-11-68.

Wani HU, Al Omair A, Al Shakweer W, Ahmed B. Schwannoma of the ascending colon with ileocolic intussusception. Trop Gastroenterol. 2010;31:337–9. PMID: 21568158

Kienemund J, Liegl B, Siebert F, Jagoditsch M, Spuller E, Langner C. Microcystic reticular schwannoma of the colon. Endoscopy. 2010;42(Suppl 2):E247. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0030-1255606.

Hsu KF, Lin CT, Wu CC, Hsiao CW, Lee TY, Mai CM, et al. Schwannoma of the rectum: report of a case and review of the literature. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2010;102:289–91. PMID: 20486757

Wilde BK, Senger JL, Kanthan R. Gastrointestinal schwannoma: an unusual colonic lesion mimicking adenocarcinoma. Can J Gastroenterol. 2010;24:233–6. PMID: 20431810

Mysorekar VV, Rao SG, Jalihal U, Sridhar M. Schwannoma of the ascending colon. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2010;53:198–200. https://doi.org/10.4103/0377-4929.59241.

Lee SM, Goldblum J, Kim KM. Microcystic/reticular schwannoma in the colon. Pathology. 2009;41:595–6. PMID: 19900114

Chetty R, Vajpeyi R, Penwick JL. Psammomatous melanotic schwannoma presenting as colonic polyps. Virchows Arch. 2007;451:717–20. PMID: 17622556

Braumann C, Guenther N, Menenakos C, Junghans T. Schwannoma of the colon mimicking carcinoma: a case report and literature review. Int J Color Dis. 2007;22:1547–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-006-0264-9.

Zippi M, Pica R, Scialpi R, Cassieri C, Avallone EV, Occhigrossi G. Schwannoma of the rectum: a case report and literature review. World J Clin Cases. 2013;1:49–51. https://doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v1.i1.49.

Hsu CT, Hartendorp P, Turi GK, Pollack B, Babich JP, Gusten W, et al. Radiology-pathology conference: colonic schwannoma. Clin Imaging. 2007;31:23–6. PMID: 17189842

Emanuel P, Pertsemlidis DS, Gordon R, Xu R. Benign hybrid perineurioma-schwannoma in the colon. A case report. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2006;10:367–70. PMID: 17126257

Fotiadis CI, Kouerinis IA, Papandreou I, Zografos GC, Agapitos G. Sigmoid schwannoma: a rare case. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:5079–81. PMID: 16124072

Bhardwaj K, Bal MS, Kumar P. Rectal schwannoma. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2002;21:116–7. PMID: 12118926

Jacobson BC, Hirsch MS, Lee JH, Van Dam J, Shoji B, Farraye FA. Multiple asymptomatic plexiform schwannomas of the sigmoid colon: a case report and review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:801–4. PubMed PMID: 11375596

Maciejewski A, Lange D, Włoch J. Case report of schwannoma of the rectum—clinical and pathological contribution. Med Sci Monit. 2000;6:779–82.

Matsushita M, Hajiro K, Takakuwa H, Nishio A. Endoscopic removal of colonic neurinoma arising from the submucosa. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:3001–2. 11051399

Horio Y, Watanabe F, Shirakawa K, Kageoka M, Iwasaki H, Maruyama Y, et al. Schwannoma of the sigmoid colon. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:528. PMID: 11023574

Sasatomi T, Tsuji Y, Tanaka T, Horiuchi H, Hyodo S, Takeuchi K, et al. Schwannoma in the sigmoid colon: report of a case. Kurume Med J. 2000;47:165–8. PMID: 10948655

Prévot S, Bienvenu L, Vaillant JC, de Saint-Maur PP. Benign schwannoma of the digestive tract: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of five cases, including a case of esophageal tumor. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:431–6. 10199472

Tomozawa S, Masaki T, Matsuda K, Yokoyama T, Ishida T, Muto T. A schwannoma of the cecum: case report and review of Japanese schwannomas in the large intestine. J Gastroenterol. 1998;33:872–5. 9853563

Skopelitou AS, Mylonakis EP, Charchanti AV, Kappas AM. Cellular neurilemoma (schwannoma) of the descending colon mimicking carcinoma: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:1193–6. 9749505

Kakizoe S, Kuwahara S, Kakizoe K, Kakizoe H, Kakizoe Y, Kakizoe T, et al. Local excision of benign rectal schwannoma using rectal expander-assisted transanal endoscopic microsurgery. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:90–2. 9684677

Murakami N, Tanaka T, Ohmori Y, Shirouzu Y, Ishibashi S, Harada Y, et al. A case report of rectal schwannoma. Kurume Med J. 1996;43:101–6. PMID: 8709552

Sugimura H, Tamura S, Yamada H, Kusumoto S, Watanabe K, Hayashi T, et al. Benign nerve sheath tumor of the sigmoid colon. Clin Imaging. 1993;17:64–6. 8439849

Abel ME, Nehme Kingsley AE, Abcarian H, Arlenga P, Barron SS. Anorectal neurilemomas. Dis Colon Rectum. 1985;28:960–1. 4064859

Schwartz DA. Malignant schwannoma occurring with Schistosoma japonicum: a case report. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1983;13:601–5. 7170642

Cleveland BR, Cunningham PJ. Giant neurilemmoma of the transverse mesocolon. Case report Am Surg. 1966;32:461–3. 5938620

Bodner E, De los Santos EV. The malignant degeneration of a rectal neurinoma; views on the tendency of the tumors of the nerve sheaths towards malignant degeneration. Philipp J Surg Surg Spec. 1965;20:125–41. PMID: 5896930

Wang CL, Neville AM, Wong TZ, Hall AH, Paulson EK, Bentley RC. Colonic schwannoma visualized on FDG PET/CT. Clin Nucl Med. 2010;35:181–3. https://doi.org/10.1097/RLU.0b013e3181cc632a.

Catania G, Puleo C, Cardì F, et al. Malignant schwannoma of the rectum: a clinical and pathological contribution. Chir Ital. 2011;53:873–7. 11824066

Levy AD, Quiles AM, Miettinen M, Sobin LH. Gastrointestinal schwannomas: CT features with clinicopathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184:797–802. https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.184.3.01840797.

Das Gupta TK, Brasfield RD. Tumors of peripheral nerve origin: benign and malignant solitary schwannomas. CA Cancer J Clin. 1970;20:228–33. 4316984

Fletcher CD, Berman JJ, Corless C, Gorstein F, Lasota J, Longley BJ. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a consensus approach. Int J Surg Pathol. 2002;10:81–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/106689690201000201.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge a medical writer, Sandy Field, PhD, for editing this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors are responsible for the conception and design. A Bormans is responsible for the administrative support. A Bohlok, A Bormans, GL, and VD are responsible for the provision of the study materials (articles). MGG, MEK, and MV are responsible for the provision of the study materials (pathology, case report and radiology). A Bohlok, MEK, A Bormans, GL, MV, and MGG are responsible for the collection and assembly of the data. All authors did the data analysis and interpretation. A Bohlok, MEK, and GL did the manuscript writing. All authors read and gave the final approval of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The patient included in the case provided consent for her data to be used in this publication.

Consent for publication

The patient included in the case provided consent for her data to be used in this publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Bohlok, A., El Khoury, M., Bormans, A. et al. Schwannoma of the colon and rectum: a systematic literature review. World J Surg Onc 16, 125 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-018-1427-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-018-1427-1