Abstract

Background

Sacrococcygeal pilonidal disease is a chronic, well-recognized entity, characterized by the recurrent formation of an abscess or draining sinus over the sacrococcygeal area. It is one of the most common surgical problems. Rarely, chronic inflammation and recurrent disease leads to malignant transformation, most commonly to squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).

Case presentation

We describe an extremely unusual case of SCC developing in a 60-year-old patient with a chronic pilonidal sinus complicated by an anal fistula. After wide surgical excision of the pilonidal sinus and fistulas and because of the poor healing process 6 months later, colonoscopy and a percutaneous fistulography were performed, revealing an anal canal-pilonidal fistula. Patient was treated with a more radical surgical resection with a prophylactic loop colostomy, but healing was not accelerated. Multiple biopsies were then taken from the surgical site at the time, which revealed the development of SCC. CT and MRI imaging techniques revealed SCC partial invasion of the coccyx and sacrum. As a result, aggressive surgical approach was decided. Histological examination revealed moderately to poorly differentiated SCC, and the patient was treated with adjuvant radiation therapy postoperatively. Nine months later, recurrence was found in the sacrum and para-aorta lymph nodes and the patient died shortly after. We discuss the clinical features, pathogenesis, treatment options, and prognosis of this rare malignant transformation.

Conclusions

The development of SCC in chronic pilonidal disease is a rare but serious complication. Symptoms are usually attributed to the sacrococcygeal pilonidal disease (SPD), and diagnosis is often made late by histological examination of biopsies. Malignant transformation should be suspected in chronic SPD with recurrent episodes of inflammation, repeated purulent discharge, poor healing, and chronic complex fistulas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Pilonidal disease is a chronic disorder that primarily affects Caucasian boys and men between the ages of 15 and 40 years old, but rarely those over 50 years old [1–4]. It is characterized by the recurrent formation of an abscess or draining sinus over the sacrococcygeal or perianal area. It is a benign disease which, if left untreated, may result in multiple draining sinuses with chronic recurrent abscess, drainage, and soiling of clothing [5, 6]. Cases of necrotizing wound infections, sacral osteomyelitis, meningitis, and malignant degeneration associated with pilonodal disease have also been reported [7]. Malignant transformation occurs in about 0.1% of patients and usually involves squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) [2, 8, 9]. We report an extremely rare case of SCC developing in a 60-year-old man with chronic pilonidal disease complicated by an anal fistula. We also discuss the clinical features, pathogenesis, treatment options, and prognosis of this rare malignant transformation.

Case presentation

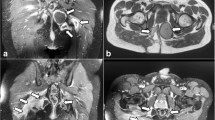

A 60-year-old man with chronic and complex sacrococcygeal pilonidal disease (SPD) was referred to our outpatient department for evaluation and management. The SPD had manifested 7 years prior to this admission. The patient reported several episodes of pilonidal abscess formation, which had resolved with either spontaneous drainage and discharge or topical incision. His past medical history was unremarkable. The patient was morbidly obese (body mass index (BMI) 49), but his nutritional status was good. Clinical examination revealed chronic SPD with complex fistulas that had formed through chronic inflammation. He underwent wide surgical excision of the pilonidal sinus, including all fistulas, and histopathological examination of the specimen revealed chronic inflammation. The surgical trauma was left to heal by secondary intention, but even 6 months later, the healing process was poor, with seropurulent discharge detected (Fig. 1a). Subsequently, colonoscopy and a percutaneous fistulography were performed, revealing an anal canal-pilonidal fistula. He underwent a more radical surgical resection (Fig. 1b), with a prophylactic loop colostomy to protect the wound. To facilitate healing, the wound was closed using the vacuum-assisted closure (VAC) technique (V.A.C; KCI International, San Antonio, TX) (Fig. 1c). However, the healing made slow progress. Multiple biopsies were then taken from the surgical site, which revealed the development of SCC (Fig. 1d).

A new colonoscopy was scheduled, and biopsies of the anal canal were obtained. These confirmed the development of SCC. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed SCC partial invasion of the coccyx and sacrum. The inguinal lymph nodes were clinically impalpable, and imaging confirmed that they were normal. We decided that an aggressive surgical approach was warranted and performed abdominoperineal resection, followed by resection of the invaded traumatic area, complete removal of the coccyx, and partial resection of the sacrum. Perforator-based flaps were used to reconstruct the defected area. The localization of perforators around the sacrum was established preoperatively by a handheld Doppler ultrasound scanner. The pedicle was secured; the rest of the flap was raised; and once the flap perfusion was satisfactory, it was carefully lifted from the donor bed and rotated around this pedicle into the recipient defect. The donor defect was closed primarily.

Histological examination revealed moderately to poorly differentiated SCC. The cells were medium to large, with moderately pleomorphic nuclei. There was focal keratinization, and the tumor exhibited a predominantly solid and focally trabecular pattern of growth. The neoplastic cells infiltrated the large bowel wall, dermis, bone, and skeletal muscle (Fig. 2a–d).

Histopathological findings. a Squamous cell carcinoma invading the wall of the large bowel (H&E ×100). b Invasion of the dermis by the neoplasm, which shows keratinization in this area (H&E ×40). c Area of bone invasion by the neoplasm (H&E ×100). d Poorly differentiated area of the neoplasm invading muscle (H&E ×100)

The patient was treated with adjuvant radiation therapy postoperatively. No adjuvant chemotherapy was offered. Despite the aggressive surgical intervention, the prognosis was poor. Recurrence was found in the sacrum and para-aorta lymph nodes 9 months after the radical surgery, and the patient died of a respiratory infection soon after this.

Discussion

SPD frequently occurs as a chronic skin infection in the region of the buttock crease or natal cleft [1, 10]. It is assumed that the disease results from the in-growth of a hair from the surrounding skin [11]. Karydakis proposed three main factors to explain how these hairs make their way into the tissues: the invader, which is the loose hair; the force, which causes the in-growth; and the vulnerability of the skin to the in-growth of the hair at the depth of the natal cleft [12]. A single midline sinus posterior to the anus is characteristic, and while most affected patients present with acute abscess, some suffer chronic infection with discomfort and a purulent discharge [13]. Additional sinuses are also frequent, often with lateral openings [14]. Pilonidal sinuses often penetrate deep into the ischioanal fossa; however, they would not be expected to penetrate the sphincters and involve the anus [7, 10]. In our patient, the fistula involved the anal canal.

Malignant transformation is a rare but well-known complication of long-standing SPD, occurring in approximately 0.1% of patients with recurrent and complex SPD [2, 8, 9, 15, 16]. SCC is the most common carcinoma associated with chronic SPD, although basal cell carcinoma, sweat gland adenocarcinoma, and verrucous carcinoma have also been reported [2, 5, 17]. The pathogenesis of malignant transformation in SPD is thought to be similar to that associated with other chronic ulcerative and scarifying cutaneous disorders, such as Marjolin’s ulcer [2]. It is believed that this process, on the molecular basis, is caused by the release of free oxygen radicals by activated inflammatory cells, inducing genetic damage and neoplastic transformation [9]. The normal repair DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) mechanism is also impaired in chronic inflammation, which predisposes to malignancy [9, 18]. These predisposing factors result in congenital duplications of the anorectal mucosa, focal adenomatous hyperplasia of the anal glands, and cancerous transformation of rectal mucosal cells that have migrated into the fistulae [19]. Immunosuppression and human papilloma virus infection may also be predisposing factors that induce and accelerate the transformation [20, 21].

Pilonidal carcinoma can be diagnosed by gross inspection, revealing an ulcer with a friable, rapidly growing, bleeding, and fungating margin, in the pilonidal cyst or sinus [22]. Multiple biopsies of the margin of the ulcer provide the histological diagnosis [15, 16]. Occasionally, the lesion is discovered incidentally in an otherwise routine histological examination of a specimen [22]. In the present case, carcinoma was suspected when the surgical wound would not heal, but the initial histopathogical examination did not reveal evidence of malignancy. It must be emphasized that all pilonidal disease specimens should be sent routinely for histopathological evaluation to rule out malignancy.

The most important consideration in the differential diagnosis of pilonidal carcinoma is pseudocarcinomatous hyperplasia of the squamous epithelium [15, 22]. In contrast to reactive hyperplasia, carcinoma will show more nuclear pleomorphism, a greater degree of dyskeratosis, atypical mitotic figures, and invasion of the surrounding connective tissue stroma [15]. As cellular atypia and an increased mitotic rate may also be seen in pseudocarcinomatous hyperplasia, adequate sampling tissue for histological examination must be taken to establish the diagnosis [15]. Preoperative evaluation should include rectal and sigmoidoscopic examinations, and the inguinal lymph nodes must be carefully palpated. CT or MRI images are indicated to demonstrate local extent, to detect intra-abdominal metastases, including the spread to the iliac and para-aortic lymph nodes, and to complement the physical examination of the inguinal lymph nodes [9, 16]. Lumbosacral and coccyx spine films should also be taken to exclude osteomyelitis or bone invasion by the tumor [15].

When there is no evidence of inguinal adenopathy, wide surgical excision is indicated, using strict oncologic techniques of en bloc resection and minimizing violation of the tumor margins and the lesion [21]. Presacral fascia, gluteal muscle, a wide margin of skin and subcutaneous tissue, and, if required, the sacrum and coccyx, should be excised [16]. Prophylactic inguinal node dissection is not recommended [15]. Surgery for superficial SCC has good results [5]. Complete excision by conventional surgery is not feasible when the tumor has become adherent to the sacrum and/or coccyx and has perforated the sacral fascia [4]. Local recurrence after surgery is common [4, 9]. Recurrence rates reach 50% and usually appear 9–16 months after surgery [4]. Adjuvant radiotherapy within a generous margin can decrease local recurrence to 30% [9]. Conversely, the role of adjuvant chemotherapy remains unclear, although it may be effective in combination with resection and radiotherapy for high-risk lesions [4–6]. Re-excision of a local recurrence may prolong survival [9]. The 5-year survival rate of patients with SPD complicated by SCC is almost 55–61% [16, 21]. It was reported that there is no relationship between the degree of tumor differentiation and survival [4].

Conclusions

In conclusion, the development of SCC in chronic pilonidal disease is a rare but serious complication. Symptoms are usually attributed to the SPD, and diagnosis is often made late by histological examination of biopsies. Malignant transformation should be suspected in chronic SPD with recurrent episodes of inflammation, repeated purulent discharge, poor healing, and chronic complex fistulas. All specimens of pilonidal disease should be sent routinely for histopathological evaluation. Histopathological studies of multiple biopsies allow us to make an accurate diagnosis of SCC and initiate aggressive surgical excision, with or without adjuvant radiotherapy, as the appropriate treatment.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- DNA:

-

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- SCC:

-

Squamous cell carcinoma

- SPD:

-

Sacrococcygeal pilonidal disease

- VAC:

-

Vacuum-assisted closure

References

Lohsiriwat V. Persistent perineal sinus: incidence, pathogenesis, risk factors, and management. Surg Today. 2009;39(3):189–93.

White TJ, Cronin A, Lo MF, Fred Huynh F, Donahoe SR, Lynch AC, et al. Don’t sit on chronic inflammation. ANZ J Surg. 2012;82:181–2.

Chatzis I, Noussios G, Katsourakis A, Chatzitheoklitos E. Squamous cell carcinoma related to long standing pilonidal-disease. EJD. 2009;19:408.

Almeida JC. A curative cryosurgical technique for advanced cancer of sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinuses. J Surg Oncol. 2012;106:504–8.

Newlin EH, Zlotecki RA, Morris CG, Hochwald SN, Riggs CE, Mendenhall WM. Squamous cell carcinoma of anal margin. J Surg Oncol. 2004;86:55–62.

Abboud B, Ingea H. Recurrent squamous-cell carcinoma arising in sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus tract: report of a case and review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:525–8.

Taylor SA, Halligan S, Bartram CI. Pilonidal sinus disease: MR imaging distinction from fistula in ano. Radiology. 2003;226:662–7.

Pandey MK, Gupta P, Khanna AK. Squamous cell carcinoma arising from pilonidal sinus. Int Wound J.2012.doi: 10.1111/j.1742-481X.2012.01096.x.

de Bree E, Zoetmulder FAN, Christodoulakis M, Aleman BMP, Tsiftsis DD. Treatment of malignancy arising in pilonidal disease. Ann of Surg Onc. 2001;8:60–4.

Chintapatla S, Safarani N, Kumar S, Haboubi N. Sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus: historical review, pathological insight and surgical options. Tech Coloproctol. 2003;7:3–8.

Patey DH, Scarff RW. Pathology of postanal pilonidal sinus: it’s bearing on treatment. Lancet. 1946;2:484–6.

Karydakis GE. New approach to the problem of pilonidal sinus. Lancet. 1973;2:1414–5.

Jones D. Pilonidal sinus. BMJ. 1992;305:410–2.

da Silva H. Pilonidal cyst. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:1146–56.

Pilipshen SJ, Gray G, Goldsmith E, Dineen P. Carcinoma arising in pilonidal sinuses. Ann of Surg. 1981;193:506–12.

Nunes LF, Castro Neto AKP, Vasconcelos RAT, Cajaraville F, Castilho J, Rezende JFN, Noguera WS. Carcinomatous degeneration of pilonidal cyst with sacrum destruction and invasion of the rectum. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88(6 Suppl 1):S59–62.

Mentez O, Akbulut M, Bagci M. Verrucous carcinoma (Buschke–Lowenstein) arisingin a sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus tract: report of a case. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2008;393:111–4.

Williamson J, Silverman FJ, Tafra L. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of metastatic squamous-cell carcinoma arising in a pilonidal sinus, with literature review. Diagn Cytopath. 1999;20:367–70.

Seya T, Tanaka N, Shinji S, Yokoi K, Oguro T, Oaki Y, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma arising from recurrent anal fistula (in Japanese with English abstract). J Nippon Med Sch. 2007;74:319–24.

Malek MM, Emanuel PO, Divino CM. Malignant degeneration of pilonidal disease in an immunosuppressed patient: report of a case and review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:1475–7.

Borges VF, Keating JT, Nasser IA, Cooley TP, Greenberg HL, Dezube BJ. Clinicopathologic characterization of squamous-cell carcinoma arising from pilonidal disease in association with condylomataacuminatum in HIV-infected patients: report of two cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:1873–7.

Velitchklov N, Vezdarova M, Losanoff J, Kjossev K, Katrov E. A fatal case of carcinoma arising from a pilonidal sinus tract. Ulster Med J. 2001;70:61–3.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Authors’ contributions

NM received the patient in our outpatient department, was the principal surgeon, and drafted the manuscript. KS revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. GR performed the pathological examination and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. SL and ET analyzed and interpreted the patient data and drafted the manuscript. IK was an auxiliary surgeon and had significant contribution to the conception and design of the manuscript. NM was responsible for the overall treatment of the patient and revised critically the manuscript and has given final approval of the version to be published. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s closest relatives for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Series Editor of this journal.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Michalopoulos, N., Sapalidis, K., Laskou, S. et al. Squamous cell carcinoma arising from chronic sacrococcygeal pilonidal disease: a case report. World J Surg Onc 15, 65 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-017-1129-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-017-1129-0