Abstract

Background

Oral Health Related Quality of Life (OHRQoL) is an important measure of disease and intervention outcomes. Chronic periodontitis (CP) is an inflammatory condition that is associated with obesity and adversely affects OHRQoL. Obese patients with CP incur a double burden of disease. In this article we aimed to explore the effect of Non-Surgical Periodontal Therapy (NSPT) on OHRQoL among obese participants with chronic periodontitis.

Materials and Methods

This was a randomised control clinical trial at the Faculty of Dentistry, University of Malaya. A total of 66 obese patients with chronic periodontitis were randomly allocated into the treatment group (n=33) who received NSPT, while the control group (n=33) received no treatment. Four participants (2 from each group) were non-contactable 12 weeks post intervention. Therefore, their data were removed from the final analysis. The protocol involved questionnaires (characteristics and OHRQoL (Oral Health Impact Profile-14; OHIP-14)) and a clinical examination.

Results

The OHIP prevalence of impact (PI), overall mean OHIP severity score (SS) and mean OHIP Extent of Impact (EI) at baseline and at the 12-week follow up were almost similar between the two groups and statistically not significant at (p=0.618), (p=0.573), and (p=0.915), respectively. However, in a within-group comparison, OHIP PI, OHIP SS, and OHIP EI showed a significant improvement for both treatment and control groups and the p values were ((0.002), (0.008) for PI), ((0.006) and (0.004) for SS) and ((0.006) and (0.002) for EI) in-treatment and control groups, respectively.

Conclusion

NSPT did not significantly affect the OHRQoL among those obese with CP. Regardless, NSPT, functional limitation and psychological discomfort domains had significantly improved.

Trial registration

(NCT02508415). Retrospectively registered on 2nd of April 2015.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Chronic periodontitis (CP) is an inflammatory disease that adversely affects aesthetic, masticatory and speech functions of individuals [1, 2]. Oral health-related quality of life is an important measure of disease and intervention outcomes, which has become an important aspect that reflects patient satisfaction in relation to the specified domains of life [3,4,5]. Several studies documented that CP has a negative impact on OHRQoL [6,7,8,9,10,11,12]. Non-surgical periodontal therapy (NSPT) is considered to be the first-line of treating CP [13, 14]. NSPT was proven to be effective in treating periodontal disease [15,16,17]; Nonetheless, studies have shown a positive impact on OHRQoL following NSPT [18, 19]. Collectively, a systematic review by Shanbhag et al. investigated the impact of periodontal-disease treatment modalities on OHRQoL and concluded that NSPT can moderately improve OHRQoL in CP subjects, whereas other treatment modalities showed no significant difference [20].

Obesity was positively associated with periodontal disease and it was indicated as a risk factor for the development of CP [21]. Both experimental [22, 23] and observational [24,25,26,27] studies, which were confirmed with systematic reviews and meta-analysis [28, 29] ascertained the association of obesity and CP.

Oral health problems can affect a person’s perception of oral well-being, as well as their social and physical oral functioning. In addition, ORHQoL may indirectly affect obesity, difficulty in chewing may result in avoiding nutritious food like vegetables or might lead to overcooking, which reduces the nutrients and eventually leads to malnutrition or obesity [30, 31].

Owing to the fact that dental care constitutes a significant portion of yearly healthcare costs [32] accompanied by the increasing prevalence of obesity, obese individuals with CP incur a double burden of disease and a double jeopardy to their overall QOL.

The prevalence of being overweight and obesity is increasing with alarming figures in Malaysia, where it reached 33.6% and 19.5%, respectively [33]. Moreover, most studies of CP treatment with NSPT were done on the general population, and not exclusively in the obese. Thus, we felt the necessity of undertaking this study, particularly to patch the gap of knowledge regarding the impact of NSPT among obese individuals with CP.

Therefore, this study aims at assessing the impact of NSPT on OHRQoL among obese patients compared to controlled obese patients. We hypothesized that the treatment group will have improvement in ORHQoL.

Methods

This was a randomized controlled clinical trial at the Faculty of Dentistry, University of Malaya. Ethical approval was granted by the Medical Ethics Committee, Faculty of Dentistry/University of Malaya (DFOP 1213/0079 (L)).The study was retrospectively registered in ClinicalTrials.gov as NCT02508415. Participants were recruited from October 1st, 2013 until April 30th, 2014. Obese is defined as an individual who has a BMI ≥ 27.5 kg/m2 [34].

Participants

Patients with CP who attended the periodontal clinic at the Faculty of Dentistry were targeted in this study, those who fulfilled the inclusion and exclusion criteria were invited to participate in this study. The participants were screened for periodontal disease using a Basic Periodontal Examination (BPE).

The inclusion criteria included (i) Malaysians, (ii) BMI ≥ 27.5 kg/m2, (iii) aged≥ 30 years old, (iv) those who have at least 12 teeth and (v) diagnosed with CP. The exclusion criteria included those who (i) have received periodontal treatment within the past 6 months (ii), were on antibiotics within the past 4 months (iii), require prophylactic antibiotic coverage (iv), were on systemic or topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for the past 4 months (v), are pregnant or intend to and lactating mothers (vi), are mentally handicapped, (vii) have rheumatic heart disease (viii), and had a valve replacement. Informed consent was obtained prior to commencement of treatment.

Sample size

A total of 66 participants who were obese (BMI ≥ 27.5 kg/m2) and diagnosed with CP [35] participated in this study. The sample size was calculated based on the mean difference between test and control groups. We estimated that a total of 30 cases in each group was sufficient to detect a mean SS difference of 5 with 80% power of study. The parameters used in the sample size calculation were derived from the most comparable published data. Due to the anticipated 10% drop-out from previous studies [11, 36], the total sample size was 66.

Randomization

Simple randomization technique was employed in this study using research randomizer software. Each participant was assigned a number from 1-66. A research assistant assigned the number to the participants to ensure complete concealment and optimum randomization. Then, the list was entered to the software that randomly allocate a specified number of participants into two groups; treatment and control.

Data collection procedure

The procedure for clinical examination and NSPT was previously described by Akram et al. [9] in which demographic data and physical examination were assessed along with BPE. Participants were asked to complete OHIP-14 questionnaires with supervision of the research assistant. Periodontal parameters, including periodontal pocket depth (PPD) and recession (R) were carried out using a Williams Probe (Hu-Friedy, Chicago USA) at 6 sites per tooth. Clinical Attachment Loss (CAL) was calculated by the sum of PPD and R and was registered manually.

Intervention

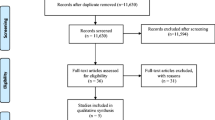

The intervention group received an oral hygiene education, which included the use of a toothbrush, interdental brush and dental floss utilizing the modified Bass technique, and were also instructed to use a 0.12% Chlorhexidine mouth rinse. Scaling and root planning were conducted by the investigator within a single session using an ultrasonic scaler (SATELEC P5 Newtron XS, UK) and Gracey curettes (Hu-Friedy, Chicago, IL, USA). At 12 weeks, a recall visit was carried out in which re-motivation and professional prophylaxis was performed for the participants in the intervention group. On the other hand, the control group did not receive any oral hygiene education or NSPT and only an evaluation was performed including objective clinical and subjective OHRQoL assessment. Figure 1 outlines the study protocol.

Outcomes

The OHRQoL was measured using the Oral Health Impact Profile-14 (OHIP-14), the shorter version of the Malaysian OHIP [37]. The questionnaire consisted of 14 questions based on 7 domains: functional limitations, physical pain, psychological discomfort, physical disability, psychological disability, social disability, and handicap. The participants were interviewed by trained interviewers for OHIP-14 to rate their OHRQoL based on a Likert scale ranging from (1) very often, (2) quite often, (3) sometimes, (4) seldom, (5) never, and (6) don’t know. Data input was carried out when (i) 20% of data (≥2 items from OHIP-14 questionnaires) were missing, (ii) blank entries or (iii) ‘don’t know’ responses, using all the mean scores of overall participants for each of the 14 questions. Three parameters of OHIP-14 were assessed, namely: prevalence of impact (PI), severity score (SS), and extent of impact (EI) [38]. PI is the percentage of participants reporting ≥1 impacts ‘very often/often’. SS is the sum of response code for 14 items, ranging from 14-70. Lower values indicate higher impact. EI is the number of items that were reported as very often/often for each subject. Both treatment and control groups completed the OHIP-14 question at baseline prior to administration of NSPT and during the 12 week follow up.

Statistical analysis

All data were entered and analysed using SPSS version 20. Numerical variables were described with mean (± SD) and categorical variables with frequency and percentage. The association of paired categorical data was assessed with Cochrane’s Q test. A repeated measure ANOVA was used to test within- and between-group mean differences. The significance level was set at 0.05. Data was analysed with intention to treat strategy.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of the participants are summarized in Table 1. Based on the characterisation of the participants, females were the predominant group with about 74% and 68% in the treatment and the control groups, respectively. The majority of the participants belonged to the Malay ethnic group, with 64.5% in the treatment and 77.4% in the control group. Equal distribution of participants was observed in primary, secondary, and tertiary education as well as others for both groups. The majority of the participants were non-smokers (84-91%) and non-alcoholic (84%) for both groups. The mean age was about 45 years for both groups. The mean BMI was about 32 to 35 kg/m2 for both groups. There was no significant difference between treatment and control groups, with regards to gender, ethnicity, levels of education, social habits, alcohol consumption, mean age, and BMI (p >0.05).

At baseline, periodontal parameters (PPD, R & CAL) showed no significant difference between groups. However, 3 months later, improvement in periodontal parameters was significant between treatment and control groups (p <0.05) (Table 2).

Table 3 shows the comparisons for the within and between groups for OHIP-14 PI, SS and EI. At baseline, OHIP-14 PI, SS and EI were comparable for both groups. The overall OHIP PI was measured at baseline and 12 weeks for each group. The PI between groups were almost similar at baseline and 12 weeks post-NSPT (p =0.618). However, within-group comparison showed a significant difference for treatment (p =0.002) and control (p=0.008) groups. The overall mean OHIP SS increased significantly (p <0.05) in both treatment and control groups, however between groups difference was not significant (p =0.573). The overall mean OHIP EI was not statistically different at baseline and 12 weeks follow up for treatment and control groups, but it was reduced significantly within each study group 12 weeks later (treatment group p <0.006) and (control group p <0.002) (Table 3). Table 4 summarises changes in PI for all items at 12 weeks post treatment for both treatment and control groups. Most items showed non-significant reduction in PI. Nonetheless, a significant difference (p <0.05) was observed for bad breath and food impaction items. The attrition rate was 6%. Sensitivity analysis showed no difference in the results due to the attrition of 4 participants.

Discussion

RCTs are considered to be the highest level of evidence that helps professionals evaluating intervention. The actual benefit of an intervention is measured to what extent it has impact on patient expectations and wellbeing.

The results of this study demonstrated that OHIP PI, SS and EI showed no substantial difference between treatment and control groups at baseline and 12 weeks later. However, among within-groups, there was a significant improvement of OHRQoL as measured with OHIP-14.

The actual change in patient perception was often attributed to the improvement of clinical status, which is objectively measured by the health profession. The conceptual model underlies the development of OHIP-14 and includes a biopsychosocial pathway in which the perception of QOL is related to health problems. Consequently, there are two different assessments involved: (i) measurement of clinical parameters by clinician, and (ii) measurement of OHRQoL as perceived by patients. The earlier measurement was based on signs and symptoms presented by patient, and clinicians use them as indicators of health and disease status. The latter measurement was based on what the patient perceives as affecting the OHRQoL. The patient-centred assessment is more salient to patients with CP where a patient’s concerns may differ from the traditional clinical endpoints [39, 40].

The results of this study came in line with other studies where the change in QOL occurred within-groups only. Although a longer study duration was expected to influence the outocme, two different educational programs were intorduced in a RCT, in which OHRQoL was improved after 12 months, but there was no difference between the two programs [41]. Similarly, a difference was not significant between the two groups, which were assigned different oral hygiene educational programs. Moreover, the intervention group showed better improvement [42]. Other studies showed similar results without a reasonable justification of such trends [43], [44].

CP is known for its silent disease nature and progresses slowly. Most patients might not be aware of suffering from CP because the condition does not commonly involve pain. The slow progressive nature of CP allows a patient to adapt to clinically presenting symptoms, such as food trapped and mobile tooth. Therefore, little or limited perception from patients to acknowledge CP as a condition may affect the OHRQoL.

A recent study on the same sample as reported by Akram et al. demonstrated that a within-group comparison showed improvement in all clinical periodontal parameters (Plaque score (PS), Gingival bleeding index (GBI), PPD and CAL) in both the treatment and control group at 12 weeks [45]. However, at 3 months, between-group comparison showed significant improvement in PS for the treatment group compared to the control group. NSPT was shown to be effective in improving clinical parameters among those obese with CP. Moreover, NSPT was shown to effectively improve PPD and CAL in shallow and moderately deep periodontal pockets, but not in deep periodontal pockets. Taken together, it is interesting to note that NSPT can provide better clinical outcomes, while the OHRQoL remains the same in that it does not have an impact on OHRQoL among those obese with CP.

It is interesting to note that both treatment and control groups presented with a high mean OHIP SS at baseline and 12 weeks post treatment. However, the differences in change for OHIP SS were significant (p<0.05). In the treatment group, the improvement observed could be attributed to the OHI and motivation as well as root surface debridement provided. Nevertheless, the improvement observed in the control group might be attributed to the tendency of persons to improve their performance when they are participating in an experiment. Individuals may change their behaviour due to the attention they are receiving from observers rather than because of any manipulation [46, 47].

The differences in change were based on participants’ perceptions and hence, these differences were probably much more relevant to the participants’ daily life. The mean EI at 12 weeks post NSPT showed significant reduction for both treatment and control groups at 0.47 (0.91) and 0.65 (1.02), respectively. These findings showed an overall improvement in the QoL (treatment: p < 0.006; control: p < 0.002), and this suggested that there was a significant improvement at the subject’s self-perception level of OHRQoL.

A detailed comparison of the OHIP-14 items revealed that only 2 out of 14 items were significantly reduced (p<0.05). The two items were ‘bad breath’ (functional limitation domain) and ‘food impaction’ (psychological discomfort domain). Previous studies in various populations were in agreement with the current findings, in terms of improvement in the ‘food impaction’ item [19] [48]. Improvement in ‘food impaction’ following NSPT in all the studies would be expected. Furcation involvement in molar teeth is a common clinical feature in moderate and severe CP. Similarly, as CP progresses, it involves alveolar bone resorption around the tooth, and wider interdental spaces will be observed that results in a food trap. Following NSPT, the severity of the condition may be reduced as those in the treatment group were now better able to clean the interdental areas using OHE knowledge. Other than the ‘psychological discomfort’ domain, the aforementioned studies also reported common impacts of OHIP PI related to physical pain following NSPT [19, 48]. In addition, Brauchle et al., also reported the positive impact of NSPT on OHRQoL at the social domain in those with CP [48].

Variation in response for specific item(s)/domain(s) involved between studies may be attributed to several factors. The OHIP questionnaire was originally developed using data from an oral health survey of older adults to examine the associations between OHIP scores and a variety of clinical indicators, such as tooth loss, caries and periodontal disease. In addition, OHIP-14 is not a condition-specific measure, i.e. the reported improvement in OHRQoL was not necessarily due to the resolution of the periodontal disease upon follow up [49]. Another possibility that the duration of 12 weeks was not enough to capture the changes were as seen in other studies where the follow up continued for approximately one year.

Previous studies raised concerns about difficulties in assessing the association between objective measures of dental diseases (e.g. dental caries and periodontal disease) and patient-based opinions of oral status. There was a weak relationship between the two and the objective measures may not accurately reflect patients' perceptions [49, 50]. These authors acknowledged that the results must be interpreted with care since the majority of the responses were unchanged with no impact on OHRQoL. In addition, prolonged exposure to CP could have led to a decrease in sensitivity of participants to the OHIP instruments. The level of awareness of patients regarding their CP status could also potentially influence the impact on responses. It could be anticipated that responses could differ in participants who are aware compared to those who are unaware of their periodontal condition [33]. It is possible that our Malaysian obese population could have (i) different aesthetic or social demands that dictate their perception towards disease, or (ii) do they pay attention to periodontal health since they were obese or possibly (iii) have more serious issues to deal with than their ‘less’ serious condition in the mouth.

It might be argued that our study is underpowered with a small sample size. Reports with similar outcomes recruited an almost comparable sample size with results consistent to this study [18, 19, 43, 51, 52]. Therefore, the argument might not be relevant.

Although we adopted a systematic approach in conducting the study and reporting the results, there were several inevitable limitations for this study: (i) failure of blinding the study groups because it involves active participation or otherwise. This might have caused a Hawthorn effect on the control group (ii), Impact of obesity on Quality of Life was not measured, (iii) In-line with other RCT, some ethical concerns were identified in regards to depriving the control group from the intervention, however, this was offset by the fact that those patients were not generally aware of their condition and the study offered them a diagnosis and treatment after the completion of the trial.

Conclusion

NSPT does improve the OHRQoL in obese with CP; however, this clinical improvement was not statistically significant at a subjective level. Regardless, NSPT, functional limitation and psychological discomfort domains were significantly improved in obese with CP particularly in regards to the items, ‘food impaction’ and ‘bad breath’.

Implications of the study

Few implications can be deduced from our study. Simple protective measures, such as NSPT can be provided at the primary dental care clinic and may be of supreme help to reduce the cost of treating CP as well as reducing the burden of disease. Assessment of QOL would be better combining specific and generic QOL measures. The results of this study add to evidence on the impact of NTSP on CP among obese patients and highlights that possible precautions need to be taken in similar studies. This study is reflective of a selected Asian population and could provide a path for future researchers to relate to our findings.

Abbreviations

- CAL:

-

Clinical Attachment Level

- CP:

-

Chronic Periodontitis

- EI:

-

Extent of Impact

- GBI:

-

Gingival Bleeding Index

- NSAIDs:

-

Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs

- NSPT:

-

Non-Surgical Periodontal Therapy

- OHIP:

-

Oral Health Impact Profile

- OHRQoL:

-

Oral Health-Related Quality of Life

- PI:

-

Prevalence of Impact

- PPD:

-

Periodontal Pocket Depth

- PS:

-

Plaque Score

- SS:

-

Severity Score

References

Shaddox LM, Walker CB. Treating chronic periodontitis: current status, challenges, and future directions. Clin Cosmet Investig Dent. 2010;2:79–91.

Costa FO, Susin C, Cortelli JR, Pordeus IA. Epidemiology of periodontal disease. Int J Dentistry. 2012;2012

Bennadi D, Reddy C. Oral health related quality of life. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2013;3(1):1.

Locker D, Allen F. What do measures of ‘oral health-related quality of life’measure? Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2007;35(6):401–11.

Allen PF. Assessment of oral health related quality of life. Health Quality Life Outcomes. 2003;1(1):40.

Mourão LC, de Matos Cataldo D, Moutinho H, Canabarro A. Impact of chronic periodontitis on quality-of-life and on the level of blood metabolic markers. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2015;19(2):155.

Goel K, Baral DA. Comparison of Impact of Chronic Periodontal Diseases and Nonsurgical Periodontal Therapy on Oral Health-Related Quality of Life. Int J Dent. 2017;2017

Meusel DR, Ramacciato JC, Motta RH, Júnior RBB, Flório FM. Impact of the severity of chronic periodontal disease on quality of life. J Oral Sci. 2015;57(2):87–94.

Musurlieva N, Stoykova M. Evaluation of the impact of chronic periodontitis on individual's quality of life by a self-developed tool. Biotechnol Biotechnol Equip. 2015;29(5):991–5.

Cunha-Cruz J, Hujoel P, Kressin N. Oral health-related quality of life of periodontal patients. J Periodontal Res. 2007;42(2):169–76.

Durham J, Fraser HM, McCracken GI, Stone KM, John MT, Preshaw PM. Impact of periodontitis on oral health-related quality of life. J Dent. 2013;41(4):370–6.

Zucoloto ML, Maroco J, Campos JADB. Impact of oral health on health-related quality of life: a cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health. 2016;16(1):55.

Drisko CH. Nonsurgical periodontal therapy. Periodontol 2000. 2001;25(1):77–88.

Greenstein G. Nonsurgical periodontal therapy in 2000: a literature review. J Am Dental Assoc. 2000;131(11):1580–92.

Heitz-Mayfield L, Trombelli L, Heitz F, Needleman I, Moles D. A systematic review of the effect of surgical debridement vs. non-surgical debridement for the treatment of chronic periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2002;29(s3):92–102.

Van der Weijden G, Timmerman M. A systematic review on the clinical efficacy of subgingival debridement in the treatment of chronic periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2002;29(s3):55-71.

Kwon T, Levin L. Cause-related therapy: A review and suggested guidelines. Quintessence International. 2014;45(7)

Shah M, Kumar S. Improvement of oral health related quality of life in periodontitis patients after non-surgical periodontal therapy. indian Journal of dentistry. 2011(2):26-29.

Wong R, Ng SK, Corbet EF, Keung Leung W. Non-surgical periodontal therapy improves oral health-related quality of life. Journal of clinical periodontology. 2012;39(1):53–61.

Shanbhag S, Dahiya M, Croucher R. The impact of periodontal therapy on oral health-related quality of life in adults: a systematic review. Journal of clinical periodontology. 2012;39(8):725–35.

Jagannathachary S, Kamaraj D. Obesity and periodontal disease. Journal of Indian Society of Periodontology. 2010;14(2):96.

Cavagni J, Wagner TP, Gaio EJ, Rêgo ROCC, da Silva Torres IL, Rösing CK. Obesity may increase the occurrence of spontaneous periodontal disease in Wistar rats. Archives of oral biology. 2013;58(8):1034–9.

do Nascimento CM, Cassol T, da Silva FS, Bonfleur ML, Nassar CA, Nassar PO. Radiographic evaluation of the effect of obesity on alveolar bone in rats with ligature-induced periodontal disease. Diabetes, metabolic syndrome and obesity: targets and therapy. 2013;6:365.

Khan S, Saub R, Vaithilingam RD, Safii SH, Vethakkan SR, Baharuddin NA. Prevalence of chronic periodontitis in an obese population: a preliminary study. BMC oral health. 2015;15(1):114.

Palle AR, Reddy CSK, Shankar BS, Gelli V, Sudhakar J, Reddy KKM. Association between obesity and chronic periodontitis: a cross-sectional study. The journal of contemporary dental practice. 2013;14(2):168.

Hegde S, Kumar A. Obesity and its association with Chronic Periodontitis-A pilotstudy. IOSR Journal of Dental and Medical Sciences (IOSR-JDMS). 1(13):66–9.

Prpic J, Kuis D, Glazar I, Ribaric SP. Association of obesity with periodontitis, tooth loss and oral hygiene in non-smoking adults. Central European journal of public health. 2013;21(4):196.

Suvan J, D'Aiuto F, Moles DR, Petrie A, Donos N. Association between overweight/obesity and periodontitis in adults. A systematic review. Obesity Reviews. 2011;12(5):e381–404.

Chaffee BW, Weston SJ. Association between chronic periodontal disease and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of periodontology. 2010;81(12):1708–24.

Walls AW, Steele JG, Sheiham A, Marcenes W, Moynihan PJ. Oral health and nutrition in older people. Journal of public health dentistry. 2000;60(4):304–7.

Sheiham A, Steele J, Marcenes W, Lowe C, Finch S, Bates C, et al. The relationship among dental status, nutrient intake, and nutritional status in older people. Journal of dental research. 2001;80(2):408–13.

Turner L. Cross-border dental care:'dental tourism'and patient mobility. British dental journal. 2008;204(10):553–4.

Mohamud WNW, Musa KI, Khir ASM, Aa-S I, Ismail IS, Kadir KA, et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among adult Malaysians: an update. Asia Pacific journal of clinical nutrition. 2011;20(1):35–41.

Barba C, Cavalli-Sforza T, Cutter J, Darnton-Hill I. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. The lancet. 2004;363(9403):157.

Eke PI, Page RC, Wei L, Thornton-Evans G, Genco RJ. Update of the case definitions for population-based surveillance of periodontitis. Journal of periodontology. 2012;83(12):1449–54.

Ulinski KGB, do Nascimento MA, Lima AMC, Benetti AR, Poli-Frederico RC, Fernandes KBP, et al. Factors related to oral health-related quality of life of independent brazilian elderly. International Journal of Dentistry. 2013;2013

Saub R, Locker D, Allison P. Derivation and validation of the short version of the Malaysian Oral Health Impact Profile. Community dentistry and oral epidemiology. 2005;33(5):378–83.

Locker D. Oral health and quality of life. Oral health & preventive dentistry. 2003;2:247–53.

Jowett AK, Orr MT, Rawlinson A, Robinson PG. Psychosocial impact of periodontal disease and its treatment with 24-h root surface debridement. Journal of clinical periodontology. 2009;36(5):413–8.

Ng SK, Keung Leung WA. community study on the relationship between stress, coping, affective dispositions and periodontal attachment loss. Community dentistry and oral epidemiology. 2006;34(4):252–66.

Jönsson B, Öhrn K. Evaluation of the effect of non-surgical periodontal treatment on oral health-related quality of life: estimation of minimal important differences 1 year after treatment. Journal of clinical periodontology. 2014;41(3):275–82.

Jönsson B, Öhrn K, Lindberg P, Oscarson N. Evaluation of an individually tailored oral health educational programme on periodontal health. Journal of clinical periodontology. 2010;37(10):912–9.

Tsakos G, Bernabé E, D'aiuto F, Pikhart H, Tonetti M, Sheiham A, et al. Assessing the minimally important difference in the oral impact on daily performances index in patients treated for periodontitis. Journal of clinical periodontology. 2010;37(10):903-909.

D'avila GB, Carvalho LH, Feres-Filho EJ, Feres M, Leão A. Oral health impacts on daily living related to four different treatment protocols for chronic periodontitis. Journal of periodontology. 2005;76(10):1751–7.

Akram Z, Safii SH, Vaithilingam RD, Baharuddin NA, Javed F, Vohra F. Efficacy of non-surgical periodontal therapy in the management of chronic periodontitis among obese and non-obese patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical oral investigations. 2016;20(5):903–14.

Hawthorne ME. the Western Electric Company: the social problems of an industrial civilisation. London, United Kingdom: Lowe & Brydone Printers Ltd.; 1949.

McCarney R, Warner J, Iliffe S, Van Haselen R, Griffin M, Fisher P. The Hawthorne Effect: a randomised, controlled trial. BMC medical research methodology. 2007;7(1):30.

Brauchle F, Noack M, Reich E. Impact of periodontal disease and periodontal therapy on oral health-related quality of life. International dental journal. 2013;63(6):306–11.

Locker D, Slade G. Association between clinical and subjective indicators of oral health status in an older adult population. Gerodontology. 1994;11(2):108–14.

Gooch B, Dolan T, Bourque L. Correlates of self-reported dental health status upon enrollment in the Rand Health Insurance Experiment. Journal of Dental Education. 1989;53(11):629–37.

Ozcelik O, Haytac MC, Seydaoglu G. Immediate post-operative effects of different periodontal treatment modalities on oral health-related quality of life: a randomized clinical trial. Journal of clinical periodontology. 2007;34(9):788–96.

Saito A, Hosaka Y, Kikuchi M, Akamatsu M, Fukaya C, Matsumoto S, et al. Effect of initial periodontal therapy on oral health–related quality of life in patients with periodontitis in Japan. Journal of periodontology. 2010;81(7):1001–9.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge University of Malaya and Ministry of Higher Education for the contribution in funding the study. In addition, we want to express our appreciation to all participants who make their best efforts to participate actively in this study.

Funding

This study was funded by the University Malaya postgraduate grant (PG066-2013B), University Malaya Research Grant, Kuala Lumpur Malaysia (UMRG-RP031A/14HTM) and Ministry of Education Research Grant (HIR/MOHE/DENT/04).

Availability of data and materials

Data available upon request

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NAB initiated the idea and design of the study, as well as revised and edited the initial and final draft. SSB authored the initial draft, carried out periodontal examination, OHIP-14 questionnaires, collection of epidemiological data and revised the final draft. FHA, RS, RDV and SHS were involved in initial conception of the project design, revised drafts and edited the final draft. AMD performed the statistical analysis, revised and edited the article. All authors gave final approval and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was granted by the Medical Ethics Committee, Faculty of Dentistry University of Malaya (DFOP 1213/0079 (L) and was retrospectively registered in ClinicalTrials.gov as NCT02508415. Participants were recruited from October 1st, 2013 until April 30th, 2014.

Participants were screened based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Those who fulfilled the criteria were invited agreed to participate in the study. Then these participants were given a Patient Information Sheet (PIS) regarding the procedure involved and were required to sign a written consent form prior to commencement of treatment. The PIS document is the summary of the purpose, procedure, possible benefits and drawbacks of the study. The PIS was available in two languages: English and Bahasa Melayu (see Additional file 1). This consent form was also available in two languages: English and Bahasa Melayu (see Additional file 2).

Consent for publication

Participants were required to sign a written consent form prior to commencement of treatment. This consent form was also available in two languages: English and Bahasa Melayu (see Additional file 2).

Competing interests

Basher S.S, Saub R., Vaithilingam R.D, Safii S.H., Aqil M. Daher, Al-Bayaty F.H, and Baharuddin N.A. have stated explicitly that there is no conflict of interest in connection with this article.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Patient Information Sheet (ZIP 980 kb)

Additional file 2:

Consent Form (ZIP 818 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Basher, S.S., Saub, R., Vaithilingam, R.D. et al. Impact of non-surgical periodontal therapy on OHRQoL in an obese population, a randomised control trial. Health Qual Life Outcomes 15, 225 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-017-0793-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-017-0793-7