Abstract

In this paper we analyzed whole-genome genetic information provided by GAW20 from the Genetics of Lipid Lowering Drugs and Diet Network (GOLDN) study for family data. Lipid levels such as triglycerides (TGs) and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) are measured at different time points before and after administration of an anti-inflammatory drug fenofibrate. Apart from that, the data contain some covariates and whole-genome genotype information. We propose 2 novel approaches based on Henderson’s iterative mixed model to identify associated loci corresponding to (a) inflammatory biomarkers like TGs and HDLs together over time, and (b) the response to fenofibrate treatment. We developed a mixed-model approach using both TG and HDL phenotypes at all 4 time points for a genetic association study whereas we used TGs only to study genetic association with response to the drug. We expect that use of complete family data in a longitudinal framework under a single model involving the appropriate correlation structures would be able to exploit the maximum possible information contained in the sample. Our analysis of whole-genome single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and genomic regions corresponding to drug treatment finds no significant locus after multiple correction. Arguably, the moderately small sample size of the data set, as compared to the sample size usually used in genome-wide association studies (GWAS), could be a reason for such a result. Nevertheless, we report the top 20 SNPs associated with the phenotypes, and the top 20 SNPs and genomic regions associated with a response to fenofibrate treatment. Application of our methods to larger GWAS and further functional validation of the reported top SNPs and genomic regions might provide important biological insight into the genetic constitution of the trait.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Understanding the genetic architecture underlying complex phenotypes is crucial in decoding disease mechanisms as well as treatment and drug development. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have contributed significantly to the identification of associated variants with numerous traits. Although the sample size requirement of GWAS is high, the proportion of the disease risk explained by a single variant always remains low. However, availability of longitudinal data on multiple phenotypes might carry more information in identifying associated variants. The Genetics of Lipid Lowering Drugs and Diet Network (GOLDN) study provides a data set with triglyceride (TG) and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) levels at 4 time points for a fixed set of families with few missing observations during follow-up. Consequently, given a moderate sample size, reduction of the multiple testing burden and/or use of longitudinal information is required. Moreover, with available data on multiple interacting phenotypes, it is informative to study both the inherent environmental correlation and the genetic correlation.

Increased levels of TG and decreased HDL levels are well-known causes of heart disease. So we developed one model that captures the genome-wide genetic association with interacting phenotypes, that is, TG and HDL, over time by introducing both a temporal covariance structure and a genetic covariance structure between phenotype measurements. Our method is expected to increase power as a result of the inclusion of more information through genetic and environmental correlation structures.

On the other hand, fenofibrate is an antiinflammatory drug, well known for TG-lowering effects. Some studies report modulation of a lipid response to fenofibrate as the result of genetic variants involved in lipid metabolism [1], but the response to treatment by fenofibrate varies across individuals in a population [2]. Some GWAS ventured to find associated variants behind such a response, but met no success in the sense of identifying variants significantly associated with fenofibrate response [3]. The reasons might be low sample size, noncomparable baseline lipid profiles, and environmental exposures of the individuals. Thus, along with simple GWAS, we studied multiloci association of response to fenofibrate treatment with the genomic regions, which reduces the chance of missing a moderately associated locus. We also examined the association of single variants using multiple TG and HDL phenotypes in the GOLDN study. We found that 1 single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) is associated with the TG and HDL phenotypes, although we did not find any significant SNP or gene that is associated with the drug response. It is important to note that because the sample in this study is not very large, we report a few top significant loci that might be associated with phenotype and response to drug.

Methods

We analyzed the real data provided by GAW20 (ie, GOLDN study) data set [4]. The data set contains data on age, smoking status, etc. as covariates, pedigree information, and genome-wide genetic variation, as well as TG and HDL levels measured before and after the drug at 4 time points. Information on genetic variation was available for 822 individuals, while other information, except kinship structure, had a sample size of 1105 individuals. Pedigree data was available for 4151 individuals. The kinship structure, covariates, and TG and HDL phenotypes were available for all 822 individuals, but genotype information was missing for 1 individual. Consequently, in the subsequent analysis we used the remaining 821 subjects. Next, the missing genotypes and monomorphic SNPs were removed from the analysis. For variants with only 2 observed genotypes, we eliminated the SNP if 1 genotype frequency was < 5%. We imputed missing phenotype data using a mixed-model approach under the null model, and used log–log transformation of the phenotype variables for the entire analysis. This transformation made the data normally distributed and, hence, the resultant test statistic followed a standard distribution under a null hypothesis (H0) of no association. During imputation, we assumed constant heritability, and this value was from an existing study [5]. We calculated p values using the asymptotic distribution of test statistics under H0 after Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) correction.

To meet the objectives as stated in the previous section, we first do a GWAS based on longitudinal data with TG and HDL together as phenotypes. We use a mixed model that includes environmental as well as genetic correlation structure.

With TG and HDL at all time points as response vector, our model is:

where \( {Y}^{TG}={\left({Y}_1^{TG},{Y}_2^{TG},{Y}_3^{TG},{Y}_4^{TG}\right)}^{\hbox{'}} \) and \( {Y}^{HDL}={\left({Y}_1^{HDL},{Y}_2^{HDL},{Y}_3^{HDL},{Y}_4^{HDL}\right)}^{\hbox{'}} \) denote TG and HDL respectively, at 4 time points, for n individuals. In this model, XTG and XHDL are fixed effects design matrices, where XTG = XHDL = [I4 ⊗ 1n 14 ⊗ gn], gn is the genotype vector for n individuals at a single marker locus, uTG and uHDLare random effect vectors for n individuals, and ZTG = ZHDL = 14 ⊗ In is the corresponding matrix. Here \( {\beta}^{TG}={\left({\beta}_1^{TG},{\beta}_2^{TG},{\beta}_3^{TG},{\beta}_4^{TG},{\beta}_5^{TG}\right)}^{\hbox{'}} \), where the first 4 components are temporal effects for 4 different time points that includes the drug effect and \( {\beta}_5^{TG} \) is the effect of the SNP. We assume that, \( Var\left({u}^{TG}\right)={\sigma}_{u, TG}^2K, Var\left({u}^{HDL}\right)={\sigma}_{u, HDL}^2K \) where K is the kinship matrix, Var(εTG) = ΣTG ⊗ In, Var(εHDL) = ΣHDL ⊗ In,

where \( {\sigma}_{TG}^2 \) is the common variance of TG at all 4 time points and the correlation coefficient matrix is parameterized by three parameters: ρ1, TG, ρ2, TG and ρ3, TG. Similarly we define βTG and ΣHDL. Now, denoting ρg and ρε as genetic and environmental correlations respectively, we assume the correlation structure as:

\( Var\left(\begin{array}{c}{Y}^{TG}\\ {}{Y}^{HDL}\end{array}\right)=Z\left({\Sigma}_{u, TG, HDL}\otimes K\right){Z}^{\prime }+\left({\Sigma}_{\varepsilon, TG, HDL}\otimes {I}_n\right) \) where \( Z=\left(\begin{array}{cc}{Z}^{TG}& 0\\ {}0& {Z}^{HDL}\end{array}\right), \) \( {\Sigma}_{\varepsilon, TG, HDL}=\left(\begin{array}{cc}{\Sigma}_{TG}& {\rho}_{\varepsilon }{\Sigma}_{TG}^{\frac{1}{2}}{\Sigma}_{HDL}^{\frac{1}{2}}\\ {}{\rho}_{\varepsilon }{\Sigma}_{HDL}^{\frac{1}{2}}{\Sigma}_{TG}^{\frac{1}{2}}& {\Sigma}_{HDL}\end{array}\right), \) \( {\Sigma}_{u, TG, HDL}=\left(\begin{array}{cc}{\sigma}_{u, TG}^2& {\rho}_g{\sigma}_{u, TG}{\sigma}_{u, HDL}\\ {}{\rho}_g{\sigma}_{u, HDL}{\sigma}_{u, TG}& {\sigma}_{u, HDL}^2\end{array}\right). \).

We test the null hypothesis of no genetic association of an SNP with TG and HDL using a likelihood ratio test. The asymptotic distribution of the log-likelihood ratio statistic can be shown to follow a \( {\chi}_2^2 \) distribution. We apply this test at the GWAS level after appropriate multiple-testing correction.

To address our second objective (ie, to test association of response to fenofibrate treatment), we model our data using Henderson’s mixed-model approach with adequate modification. Incorporating correlation structure among family members, we propose our model as

where Y is the vector of changes in phenotype (measured as log-log of TG) before and after the drug treatment; X is the design matrix of covariates, namely, age, smoking status, and SNP/genotypes in a genomic region (not in linkage disequilibrium); β is the associated fixed effect parameter; Z is the design matrix of random components; u is the random effect of the family; and ε is the error component. We assume \( u\sim N\left(0,{\sigma}_g^2K\right) \), where K is the kinship matrix and \( \varepsilon \sim N\left(0,{\sigma}_e^2R\right) \) independently of u. Hence, \( V(Y)={\sigma}_g^2 ZK{Z}^{\prime }+{\sigma}_e^2R \). Note that because we are dealing with family data, a non-diagonal positive definite matrix R appears in the variance-covariance matrix of ε.

During analysis, we use 778 individuals after removing those with no response either before or after drug treatment. But in case of missing response at one of the time points before (after) drug treatment, we impute it with the other response value. To calculate kinship matrix we use R package “kinship2” with the entire family data. To find association of genomic regions, we first identify the genomic regions and then remove the SNPs that are in linkage disequilibrium (r2 > 0.5). The genomic regions are basically (a) the genic regions, and (b) the intergenic regions lying between 2 consecutive genes, that overlap the genotyped SNPs in our data. We use Henderson’s iterative procedure for mixed model approach [6] after substantial modification and after adjusting for age, smoking status as fixed effects, and random genetic effect within a family. We use the restricted maximum likelihood (REML) approach to test our H0 of no association, adopting the expectation-maximization (EM) algorithm for parameter estimation.

Maximization of joint likelihood of Y and u and eq. (3) [6] provide the best linear unbiased predictors (BLUPs) for the random component under normal assumption of the response variable.

So to test the association of (a) whole-genome SNPs and (b) genomic regions, with response to the drug treatment, our null hypothesis will be, H0 : Mβ = 0 for an arbitrary p × q matrix M with rank(M) = p. Thus, if n be the number of observations and rank(M) = p, the test statistic [7],

We developed the above procedure to test association of multiple SNPs (genomic regions), which reduces the multiple-testing burden. However, this test can be seen as a single-marker association test that we have used to perform our GWAS study with appropriate multiple-testing correction.

Results

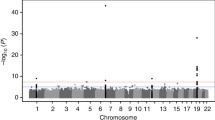

With longitudinal information using multiple phenotypes we identified only 1 significant SNP (Fig. 1) after BH correction. The SNP is rs2880301, located at TPTE2 in an intron. rs2880301 is reported to be associated with HDL particle diameter and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) particle diameter [8] and is also known to confer protection against hepatocellular carcinoma [9]. However, we think that there might be other SNPs that remain unidentified as a consequence of small sample size. Hence we report the top 20 SNPs based on p value in Table 1. rs752273 is reported to be associated with cardiovascular diseases [10] while rs2896368 is known to be associated with α1-antitrypsin level [11].

To test the null hypothesis of no association with drug response, we examined 243,593 whole-genome SNPs and 18,266 genomic regions. The genomic regions in our study are (a) genic, that overlap the genotyped SNPs, and (b) intergenic, that lie between 2 consecutive genes and overlap the genotyped SNPs in the data set. After BH correction, none of the SNPs nor genomic regions showed significant association with the drug response (Fig. 2). However, we report the top 20 SNPs (Table 2) and top 20 genomic regions (Table 3). The moderately small sample size of the data compared to most of the GWAS might be a reason behind this result. Application of our methods to larger GWAS and further functional validation of the reported top loci might provide some directive for studying inflammatory biomarkers and response to fenofibrate treatment.

Discussion and conclusions

In this paper, we developed novel methods for (a) GWAS using longitudinal data and (b) GWAS/genomic region association with response to fenofibrate treatment based on a family-based design. These methods are agnostic to the choice of phenotype and can be generalized to any such study. Although we could not detect any novel biologically relevant locus that is significantly associated with response to fenofibrate treatment, we identified a few loci that are associated with TG and HDL levels. Our belief is that the primary reason for obtaining only a small number of significant association findings is the much smaller sample size in our analyses as compared to conventional GWAS. Validation in a larger sample might throw more light on the roles of the top few significantly associated SNPs and/or genomic regions in controlling TG and HDL levels. Nevertheless, this study emphasizes the effect of administering fenofibrate to individuals with specific genetic profiles.

We pruned the available set of SNPs to an independent set of SNPs in our GWAS, primarily to reduce the multiple-testing burden. Because many studies impute SNPs, and hence augment the number of available SNPs, to explore association findings for previously reported SNPs that have not been genotyped, our strategy has a caveat in the sense of reduction in the overall power of the GWAS. Similarly, while our proposed method involves simultaneous testing of multiple SNPs within a gene in order to evaluate association at the gene level, it may yield lower powers compared to the usual single SNP analyses in GWAS.

We imputed the missing phenotype data using a known heritability value [5] and have applied the EM algorithm. Although studies show that such imputation may lead to some loss of power and hence seems to be a limitation of our current method, the intuition behind the imputation strategy was to use the maximum phenotype data in our analyses. A more general model that includes the genotype data can be developed in a likelihood framework for testing association, but this would increase substantial computational complexity while calculating the test statistic.

Association findings based on any real data set are susceptible to being false positives. If these findings validate previous reports of association, they are more likely to be true positives. In case of novel significant findings, it is necessary to either validate them in an independent data set or, alternatively, to perform extensive simulations under similar genotype and phenotype structures to evaluate the false-positive rates of the underlying test procedures.

References

Brisson D, Ledoux K, Bosse Y, St-Pierre J, Julien P, Perron P, Hudson TJ, Vohl MC, Gaudet D. Effect of apolipoprotein E, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha and lipoprotein lipase gene mutations on the ability of fenofibrate to improve lipid profiles and reach clinical guideline targets among hypertriglyceridemic patients. Pharmacogenetics. 2002;12(4):313–20.

Shen J, Arnett DK, Parnell LD, Peacock JM, Lai CQ, Hixson JE, Tsai MY, Province MA, Straka RJ, Ordovas JM. Association of common C-reactive protein (CRP) gene polymorphisms with baseline plasma CRP levels and fenofibrate response. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(5):910–5.

Aslibekyan S, Kabagambe EK, Irvin MR, Straka RJ, Borecki IB, Tiwari HK, Tsai MY, Hopkins PN, Shen J, Lai CQ, et al. A genome-wide association study of inflammatory biomarker changes in response to fenofibrate treatment in the genetics of lipid lowering drug and diet network. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2012;22(3):191–7.

Irvin MR, Zhi D, Joehanes R, Mendelson M, Aslibekyan S, Claas SA, Thibeault KS, Patel N, Day K, Jones LW, et al. Epigenome wide association study of fasting blood lipids in the genetics of lipid-lowering drugs and diet network study. Circulation. 2014;130(7):565–72.

Heckerman D, Gurdasani D, Kadie C, Pomilla C, Carstensen T, Martin H, Ekoru K, Nsubuga RN, Ssenyomo G, Kamali A, et al. Linear mixed model for heritability estimation that explicitly addresses environmental variation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(27):7377–82.

Searle SR, Casella G, McCulloch CE. Variance components. New York: Wiley; 2006.

Kennedy BW, Quinton M, van Arendonk JA. Estimation of effects of single genes on quantitative traits. J Anim Sci. 1992;70(7):2000–12.

Frazier-Wood AC, Manichaikul A, Aslibekyan S, Borecki IB, Goff DC, Hopkins PN, Lai CQ, Ordovas JM, Post WS, Rich SS, et al. Genetic variants associated with VLDL, LDL and HDL particle size differ with race/ethnicity. Hum Genet. 2013;132(4):405–13.

Ginsburg GS, Willard HF, David SP. Genomic and precision medicine: primary care, third edition. London: Academic Press; 2017.

Shendre A, Irvin MR, Wiener H, Zhi D, Limdi NA, Overton ET, Shrestha S. Local ancestry and clinical cardiovascular events among African Americans from atherosclerosis risk in communities study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(4)

Setoh K, Terao C, Muro S, Kawaguchi T, Tabara Y, Takahashi M, Nakayama T, Kosugi S, Sekine A, Yamada R, et al. Three missense variants of metabolic syndrome-related genes are associated with alpha-1 antitrypsin levels. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7754.

Funding

Publication of this article was supported by NIH R01 GM031575.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Genetic Analysis Workshop (GAW), but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study. Qualified researchers may request these data directly from GAW.

About this supplement

This article has been published as part of BMC Proceedings Volume 12 Supplement 9, 2018: Genetic Analysis Workshop 20: envisioning the future of statistical genetics by exploring methods for epigenetic and pharmacogenomic data. The full contents of the supplement are available online at https://bmcproc.biomedcentral.com/articles/supplements/volume-12-supplement-9.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SD, PKM, and IM conceived the study and developed the statistical methods; SD and PKM conducted the data analysis; IM and SG formulated the problem; SD, PKM, and IM wrote the paper; and SG reviewed the paper. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Das, S., Mondal, P.K., Ghosh, S. et al. Family-based genome-wide association of inflammation biomarkers and fenofibrate treatment response in the GOLDN study. BMC Proc 12 (Suppl 9), 41 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12919-018-0146-5

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12919-018-0146-5