Abstract

Background

Hospital clinical pharmacists have been working in many countries for many years and clinical pharmaceutical care have a positive effect on the recovery of patients. In order to evaluate the clinical effectiveness and economic outcomes of clinical pharmaceutical care, relevant clinical trial studies were reviewed and analysed.

Methods

Two researchers searched literatures published from January 1992 to October 2019, and screened them by keywords like pharmaceutical care, pharmaceutical services, pharmacist interventions, outcomes, effects, impact, etc. Then, duplicate literatures were removed and the titles, abstracts and texts were read to screen literatures according to inclusion and exclusion criteria. Key data in the literature were extracted, and Meta-analysis was conducted using the literature with common outcome indicators.

Results

A total of 3299 articles were retrieved, and 42 studies were finally included. Twelve of them were used for meta-analysis. Among the 42 studies included, the main results of pharmaceutical care showed positive effects, 36 experimental groups were significantly better than the control group, and the remaining 6 studies showed mixed or no effects. Meta-analysis showed that clinical pharmacists had significant effects on reducing systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure and shortening hospitalization days (P < 0.05), but no statistical significance in reducing medical costs (P > 0.05).

Conclusion

Clinical pharmacists’ pharmaceutical care has a significant positive effect on patients’ clinical effects, but has no significant economic effect.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Pharmaceutical care is the direct, responsible provision of medication-related care for the purpose of achieving definite outcomes [1]. Though identifying, solving and preventing medication problems, finding out prescription errors and medication-related injuries by clinical pharmacists, incidence of adverse events and rehospitalization rates could be reduced. Patient adherence of the treatment could be significantly improved and possible harm due to medication problems had been reduced after patients received their medication instructions [2]. Medication education and treatment advice from clinical pharmacists could also shorten hospital stay [3].

Studies have shown that hospital pharmaceutical care had great value in clinical and economic aspects. In a diabetes management team, participation of clinical pharmacists led to the reduction of hemoglobin, cholesterol and blood pressure in patients as well as the significantly lower cost of medication for each patient [4]. A study showed the implementation of antifungal practice guidelines by a clinical pharmacist, member of an ICU team, resulted in a 50% cost reduction in expenditure on antifungal agents [5]. However, whether there was a direct connection between this service and the improvement of patient health had been discussed. Meanwhile, costs of running pharmacy service and its economic benefits were at issue in some countries. These worries impeded the development of hospital clinical pharmacy and its universal implement. Among factors mentioned above, lack of strong, direct evidence is one potential barrier.

Although many studies noticed the clinical and economic outcomes of hospital pharmaceutical care, few systematically demonstrated and validated the effectiveness of hospital pharmaceutical care. Due to flaws in experimental design and source of literature, non-randomized controlled trials, low methodological quality of included studies or unconvincing experimental data, evidence on effectiveness and validity are still insufficient. Therefore, it is necessary to explore its clinical and economic outcomes from the scope of a more general perspective. In the present study, a systematic review and meta-analysis for pooling statistical power was conducted to systematically evaluate the clinical and economic outcomes of hospital pharmaceutical care.

Methods

Search strategy

Two researchers searched for relevant articles published in databases including Pubmed by Medline, Embase, Cochrane and CINAH (January 1992 to October 2019). Key words included pharmaceutical service/care/intervention, pharmacy service/care/intervention, pharmacist service/care/intervention and clinical outcomes, evaluations, effects, assessment, outcomes, practice. And it is supplemented by such truncated words as “service *”, “analysis *”, “evaluate *”, “effect *”, “Pharmac *”, “intervene *”, “practi *”, “impact *”. The retained researches were supplemented by access to monographs, reviews, references to published articles, and recently published Chinese and English journal articles. Two reviewers independently searched and discussed and resolved discrepancies.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies would be included when interventions or participation of clinical pharmacists were considered with detailed descriptions of services they provided. The research setting should be conducted in hospitals. The research conducted should involve intervention groups and control groups who received routine care or non-interventions from clinical pharmacists. The clinical outcomes or economic outcomes of the interventions should be evaluated. Studies only abstracts available were excluded.

Data extraction and validity assessment

The data extraction was independently carried out by the researchers using a standard electronic form Microsoft Excel 2016 and the extracted data was checked by two researchers. According to the Cochrane systematic review guidelines, combined with the aim of this study and quality assessment requirements, extracted data in the feature tables included:

-

(1)

For numbered lists Literature characteristics (Table 1): author, publication year, country, sample source, interventions, primary outcomes and effects.

-

(2)

Methodological quality assessment table: correct randomization method, hidden allocation scheme, blindness method, whether there is bias due to missing data.

When comparing the main outcomes of experimental groups and control groups, p < 0.05 was viewed statistically significant. When the primary outcomes of the experimental group were significantly better than the control group, it was marked as “positive”; and when there were no significant difference between the two groups, it was viewed as “no effect”. For studies evaluating multiple primary outcomes and not positive outcomes, those who presented at least one major positive outcome were considered as “mixed”.

Meta-analysis

In this study, Stata 15 was used for meta-analysis. After calculating the number of studies with common outcomes, systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), medical cost, and hospitalization days remained for meta-analysis. The standard mean difference (SMD) was used as the effect quantity, the significance level (or) of the combined effect quantity test was 0.05, the significance level of the heterogeneity test was 0.1, and the overall estimate was expressed by the point estimate and 95% confidence interval (95% CI). If there is significant heterogeneity such as research subjects and interventions in the studies used to perform meta-analysis, these studies would not be directly combined. Statistical consistency was assessed using chi-square tests and I2 statistics for heterogeneity. If p > 0.1, no heterogeneity was considered. If p < 0.1, heterogeneity between studies was considered.

Results

Search and study selection

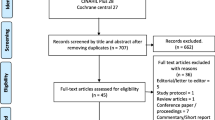

Three thousand two hundred thirty-eight documents were obtained through database searching with a manual search of 61 added references related to empirical researches on hospital pharmaceutical care. After removing duplicate articles, 2284 articles remained. Through reviewing titles and abstracts, 1634 irrelevant articles were excluded. After reading full texts, 577 articles inconsistent with this study were excluded. And 73 studies deemed suitable were assessed and excluded after screening (Fig. 1). Finally, 42 studies were included for the meta-analysis.

Summary of included studies

Relevant studies were published mainly in Europe countries and America. There were 16 studies from the United States and 5 studies from the United Kingdom; 5 studies from China; 3 studies from Australia; 2 studies from Germany and Netherlands; other studies from Singapore, Iran, France, Jordan, etc. Diseases interfered included hypertension, diabetes, nephropathy, etc. Since 2010, researches on effectiveness of hospital pharmaceutical care have greatly increased, especially in 2014. And diseases concerned shifted from traditional diseases with high-incidence to epidemic, chronic diseases. For observing changes after receiving pharmaceutical care from clinical pharmacists, most samples were inpatients. In terms of interventions, most pharmacist interventions were diverse. Patient education programs, physician advice, disease state monitor and management were referred to in most researches provided. As for effects of hospital pharmaceutical care, among the 42 articles included, 36 studies had positive effects, 5 studies had mixed effects, and one study had no effect.

Methodological quality of studies

Of the 42 studies included, 17 studies belonged to high quality studies with scores of 3–4, and the remaining 23 studies were low-quality studies (1–2 score). Among 42 studies, there were 20 randomized controlled trials, 11 non-randomized controlled trials, and 11 cohort studies. Seventeen studies reported loss of withdrawal and 20 studies reported sample baselines, taking into account the effects of randomization, blinding, and allocation concealment on selection bias, implementation bias, and measurement bias.

Meta-analysis

Meta-analysis of hospital pharmaceutical care on SBP

A total of nine studies included blood pressure data, one of which missed standard deviation of the sample, and one experiment had an uneven baseline. Results of the meta-analysis of SBP by random effects model are shown in Table 2, Fig. 2. The results of SBP heterogeneity test were significant (I2 = 82.1%, p = 0.000 < 0.1). The test results showed p = 0.000 < 0.05, indicating that hospital pharmaceutical care had a significant effect on the reduction of SBP, compared to usual care. The mean difference of SBP between the intervention groups and control groups was − 0.573 (95% CI, − 0.851 to − 0.295).

Meta-analysis of hospital pharmaceutical care on DBP

A total of nine studies included blood pressure data, one of which missed the standard deviation of the sample, and one experiment had an uneven baseline. Results of the meta-analysis of DBP by random effects model are shown as Table 3, Fig. 3. Heterogeneity test results on DBP were significant (I2 = 67.3%, p = 0.005 < 0.1). The test results showed that p = 0.002 < 0.05. It was shown that compared with usual care, hospital pharmaceutical care had significant effect on DBP. The average DBP difference between intervention group and control group was − 0.329 (95% CI, − 0.532 to − 0.125).

Meta-analysis of hospital pharmaceutical care on medical cost

A total of 15 studies included outcomes on patient medical costs, of which four experimental data missed sample standard deviations. Also, studies which had uneven baselines and did not report baselines were excluded. Here is the meta-analysis of the random effects model of medical cost indicators. The heterogeneity test of medical cost was significant (I2 = 98.3%, p = 0.000 < 0.1). The test results showed that p = 0.078 > 0.05, indicating that compared with usual care, hospital pharmaceutical care was not statistically significant on reducing medical cost. Therefore, it is not strong enough to support positive economic effect of this care on reducing the cost of patient care (Table 4, Fig. 4).

Meta-analysis of hospital pharmaceutical care on hospitalization days

A total of 11 studies covered patient days of hospitalization, of which four experimental data missed sample standard deviations and four experiments had an uneven baseline. The following is the result of a meta-analysis on the random effects model of hospital stay days. The heterogeneity test of the hospitalization days was significant (I2 = 0.0%, p = 0.513 > 0.1). The test results showed that p = 0.000 < 0.05, indicating that compared with usual care, hospital pharmaceutical care could reduce hospital stay significantly, and the average length of stay between intervention group and control group was − 2.068 (95% CI, − 3.054 to − 1.082) (Table 5, Fig. 5).

Discussion

This study systematically evaluated the clinical and economic outcomes of hospital pharmaceutical and conducted a meta-analysis. This study conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of the clinical and economic outcomes of hospital pharmaceutical care. From Table 1, the vast majority of the studies showed that clinical pharmacy interventions could improve the economic and clinical outcomes, playing a significant role in improving medication errors, reducing readmission rates, and reducing medication costs. Among the 42 studies included, the primary outcomes of this service showed positive effects, among which 36 experimental groups were significantly better than their control groups, and the remaining 6 studies showed mixed or no effect.

Overall, hospital pharmaceutical care showed positive clinical outcomes. Results of the meta-analysis showed that the intervention of pharmaceutical care had a significant effect on the reduction of SBP and DBP. Meanwhile, results of the meta-analysis showed that hospital pharmaceutical care had a significant impact on hospitalization days, but no significant effect on reducing medical cost. In an academic medical intensive care unit, a randomized controlled trial was conducted on 202 patients before the intervention and 162 patients after the intervention. This study showed that the administration of medications by the pharmacist team effectively reduced inappropriate stress of ulcer prophylaxis use [20], finally leading to reduced medical cost (p = 0.000). It might be attributed to insufficient number of relevant studies, or different calculation methods and scope for medical cost in various studies. In Carter’s research, costs associated with prescriptions and visits as well as the total cost per patient were evaluated, but no specific cost items were listed. While in Gallagher’s study [34], medical expenses covered expenses of pharmacist, non-consultant hospital physicians, senior staff nurses, inpatient days, software costs and training costs. Although studies of Carter et al. [9] and Gum [13] reported positive economic effects, their sample sizes were not large enough to support its effectiveness. The small sample size was also one of the reasons for the lack of significant results.

This study has certain limitations. First, high-quality studies and total number of studies included for meta-analysis is insufficient. Researches on pharmaceutical care carried out in hospitals with strict study design are to be updated. Second, it is difficult to determine which intervention(s) of hospital pharmaceutical care caused specific effects. How much beneficial certain pharmacy services are than other pharmacy services might be the potential problem to be settled in the future.

Conclusion

The results of meta-analysis showed that the hospital pharmaceutical care had a significant effect on reducing SBP, DBP and hospital stay, but no significant reduction on medical cost. In addition, because the data available for meta-analyses are not sufficient, a false-negative conclusion could be easily drawn. Therefore, hospital pharmaceutical care have a positive clinical and economic elimination in terms of reducing SBP, DBP and improving patient hospital stay, but follow-ups on medical cost as well as other outcomes need more experimental data to support.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- SBP:

-

Systolic blood pressure

- DBP:

-

Diastolic blood pressure

- SMD:

-

Standard mean difference

- WMD:

-

Weighted mean difference

References

Draft statement on pharmaceutical care. ASHP council on professional affairs. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1993;50(1):126–8.

Wolf C, Pauly A, Mayr A. Pharmacist-led medication reviews to identify an collaboratively resolve drug-related problems in psychiatry-a controlled, clinical trial. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0142011.

Zhang C, Zhang L, Huang L, Luo R, Wen J. Clinical pharmacists on medical care of pediatric inpatients: a single-center randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2012;7:e30856.

Xin C, Ge X, Yang X, Lin M, Jiang C, Xia Z. The impact of pharmaceutical care on improving outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus from China: a pre- and postintervention study. Int J Clin Pharm. 2014;36:963–8.

Gallagher J, Mccarthy S, Byrne S. Economic evaluations of clinical pharmacist interventions on hospital inpatients: a systematic review of recent literature. Int Jof Clin Pharm. 2014;36(6):1101.

Billi JE, Duranarenas L, Wise CG, Bernard AM, Mcquillan M, Stross JK. The effects of a low-cost intervention program on hospital costs. J Gen Intern Med. 1992;7(4):411–7.

Masters M, Krstenasky PM. Positive effect of pharmaceutical care interventions in an internal medicine inpatient setting. Ann Pharmacother. 1992;26(2):264–5.

Carter BL, Barnette DJ, Chrischilles E, Mazzotti GJ, Asali ZJ. Evaluation of hypertensive patients after care provided by community pharmacists in a rural setting. Pharmacotherapy. 1997;17(6):1274–85.

Fraser GL, Stogsdill P Jr, Dickens JD, Wennberg DE SR Jr, Prato BS. Antibiotic optimization. An evaluation of patient safety and economic outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(15):1689–94.

Gums JG, Yancey RW. HamiltonCA, Kubilis PS. A randomized, prospective study measuring outcomes after antibiotic therapy intervention by a multidisciplinary consult team. Pharmacotherapy. 1999;19(12):1369–77.

Dager WE, Branch JM, King JH, et al. Optimization of inpatient warfarin therapy: impact of daily consultation by a pharmacist-managed anticoagulation service. Ann Pharmacother. 2000;34(5):567–72.

Canales PL, Dorson PG, Crismon ML. Outcomes assessment of clinical pharmacy services in a psychiatric inpatient setting. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2001;58(14):1309–16.

Brook O, Hout HV, Nieuwenhuyse H, Heerdink E. Impact of coaching by community pharmacists on drug attitude of depressive primary care patients and acceptability to patients; a randomized controlled trial. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2003;13(1):1–9.

Bolas H, Brookes K, Scott M, McElnay J. Evaluation of a hospital-based community liaison pharmacy service in Northern Ireland. Pharm World Sci. 2004;26(2):114–20.

Carter BL, Ardery G, Dawson JD, et al. Physician and pharmacist collaboration to improve blood pressure control. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(21):1996–2002.

Wong YM, Quek YN, Tay JC, et al. Efficacy and safety of a pharmacist-managed inpatient anticoagulation service for warfarin initiation and titration. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2011;36(5):585–91.

Hammad EA, Yasein N, Tahaineh L, Albsoul-Younes AM. A randomized controlled trial to assess pharmacist- physician collaborative practice in the management of metabolic syndrome in a university medical clinic in Jordan. J Manag Care Pharm. 2011;17(4):295–303.

Shen J, Sun Q, Zhou X, et al. Pharmacist interventions on antibiotic use in inpatients with respiratory tract infections in a chinese hospital. Int J Clin Pharm. 2011;33(6):929–33.

Mousavi M, Dashtikhavidaki S, Khalili H, Farshchi A, Gatmiri M. Impact of clinical pharmacy services on stress ulcer prophylaxis prescribing and related cost in patients with renal insufficiency. Int J Pharm Pract. 2013;21(4):263–9.

Shah M, Norwood CA, Farias S, Ibrahim S, Chong PH, Fogelfeld L. Diabetes transitional care from inpatient to outpatient setting: pharmacist discharge counseling. J Pharm Pract. 2013;26(2):120–4.

Cies JJ, Varlotta L. Clinical pharmacist impact on care, length of stay, and cost in pediatric cystic fibrosis (CF) patients. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2013;48(12):1190–4.

Ho CK, Mabasa VH, Leung VW, Malyuk DL, Perrott JL. Assessment of clinical pharmacy interventions in the intensive care unit. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2013;66(4):212–8.

Chilipko AA, Norwood DK. Evaluating warfarin management by pharmacists in a community teaching hospital. Consult Pharm. 2014;29(2):95–103.

Grimes TC, Deasy E, Allen A, et al. Collaborative pharmaceutical care in an irish hospital: uncontrolled before-after study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(7):574–83.

Joost R, Dörje F, Schwitulla J, Eckardt KU, Hugo C. Intensified pharmaceutical care is improving immunosuppressive medication adherence in kidney transplant recipients during the first post-transplant year: a quasi-experimental study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014;29(8):1597–607.

Tan EC, Stewart K, Elliott RA, George J. Pharmacist consultations in general practice clinics: the pharmacists in practice study. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2014;10(4):623–32.

Vervacke A, Lorent S, Motte S. Improved venous thromboembolism prophylaxis by pharmacist-driven interventions in acutely ill medical patients in Belgium. Int J Clin Pharm. 2014;36(5):1007–13.

Zhang HX, Li X, Huo HQ, Liang P, Zhang JP, Ge WH. Pharmacist interventions for prophylactic antibiotic use in urological inpatients undergoing clean or clean-contaminated operations in a chinese hospital. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e88971.

Campo M, Roberts GW, Cooter A. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations, ‘sugar sugar’, what are we monitoring? J Pharm Pract Res. 2015;45(4):412–8.

Delpeuch A, Leveque D, Gourieux B, Herbrecht R. Impact of clinical pharmacy services in a hematology/oncology inpatient setting. Anticancer Res. 2015;35(1):457–60.

Obarcanin E, Nemitz V, Schwender H, Hasanbegovic S, Kalajdzisalihovic S. Pharmaceutical care of adolescents with diabetes mellitus type 1: the Diadema study, a randomized controlled trial. Int J Clin Pharm. 2015;37(5):790–8.

Burnett AE, Bowles H, Borrego ME, Montoya TN, Garcia DA, Mahan C. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: reducing misdiagnosis via collaboration between an inpatient anticoagulation pharmacy service and hospital reference laboratory. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2016;42(4):471–8.

Gallagher J, O’Sullivan D, Mccarthy S, et al. Structured pharmacist review of medication in older hospitalised patients: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Drugs Aging. 2016;33(4):285–94.

Khalil V, Declifford JM, Lam S, Subramaniam A. Implementation and evaluation of a collaborative clinical pharmacist's medications reconciliation and charting service for admitted medical inpatients in a metropolitan hospital. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2016;41(6):662–6.

Phatak A, Prusi R, Ward B, et al. Impact of pharmacist involvement in the transitional care of high-risk patients through medication reconciliation, medication education, and postdischarge call-backs (ipitch study). J HospMed. 2016;11(1):39–44.

Waters CD, Myers KP, Bitton BJ, Torosyan A. Reply: clinical pharmacist management of bacteremia in a community hospital emergency department. Ann Pharmacother. 2017;51(6):523.

Sloeserwij VM, Hazen AC, Zwart DL, Leendertse AJ, Poldervaart JM, de Bont AA, et al. Effects of non-dispensing pharmacists integrated in general practice on medication-related hospitalisations. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;85(10):2321–31.

Christie S, Golbarg M, Monique C, et al. The effect of clinical pharmacists on readmission rates of heart failure patients in the accountable care environment. J Manage Care Spec Pharm. 2018;24(8):795–9.

Ilktac KE, Mesut S, Kutay D. Effect of a pharmacist-led program on improving outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus from northern Cyprus: a randomized controlled trial. J Manage Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23(5):573–82.

Domingues EAM, Ferrit-Martín M, Calleja-Hernández, ángel M. Impact of pharmaceutical care on cardiovascular risk among older HIV patients on antiretroviral therapy. Int J Clin Pharm. 2017;39(1):52–60.

Andrea SO, Pedro A, Hincapié-García Jaime A, et al. Effectiveness of the Dader method for pharmaceutical care on patients with bipolar I disorder: results from the EMDADER-TAB study. J Manage Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23(1):74–84.

Javaid Z, Imtiaz U, Khalid I, Saeed H, Khan RQ, Islam M, et al. A randomized control trial of primary care-based management of type 2 diabetes by a pharmacist in Pakistan. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):1–13.

Hua S, Guoming C, Chao Z, et al. Effect of pharmaceutical care on clinical outcomes of outpatients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Patient Preference Adherence. 2017;11:897–903.

Juanes A, Garin N, Mangues MA, et al. Impact of a pharmaceutical care programme for patients with chronic disease initiated at the emergency department on drug-related negative outcomes: a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2017;25(5):274 ejhpharm-2016-001055.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GL1 conceived of the study and developed the protocol; selected the final articles for inclusion; was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. RH and JZ searched for literature and conducted the random-effects meta-analysis. GL2 and LC extracted data and served as a primary abstract and full-text article reviewer. XX guided writing and reviewed/edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, G., Huang, R., Zhang, J. et al. Clinical and economic outcomes of hospital pharmaceutical care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv Res 20, 487 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05346-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05346-8