Abstract

Background

The presence of urinary fistula after ileal conduit urinary diversion is a challenging complication, and this study investigated the role of the intra-conduit negative pressure system (NPS) in the presence of urinary fistula following ileal conduit (IC) urinary diversion as a conservative treatment.

Methods

Using the intra-conduit NPS, a minor drainage tube was placed within a silicon tube to suck urine from the conduit with consistent negative pressure. Patients with urinary fistula following IC from August 2012 to July 2017 were recorded, and the clinical characteristics and outcome were retrospectively analyzed.

Results

The intra-conduit NPS was used as a primarily conservative treatment for 13 patients who suffered from urinary fistula and presented with a large amount of abdominal/pelvic drainage without other significant morbidities. The median age was 60 years old (42–74 years), and 7patients were male. The median duration between the IC operation and the presence of urinary fistula was 15 days (2–28 days), and elevated creatinine levels were detected in the abdominal/pelvic drainage with a median level of 2114 μmol/L (636–388 μmol/L). A significant decrease in abdominal/pelvic drainage was identified in 12 patients. The median time that the NPS was used was 9 days (7–11 days). The other patient did not show any improvements after 2 days of observation and then underwent open surgery. With ureteral stenting, 2 abdominal drainage tubes and the intra-conduit NPS were placed during operation, no urine leakage was observed in the abdominal/pelvic field, and the patient was cured in 9 days. With a median follow-up of 22 months, no fistula recurrence or hydronephrosis was detected.

Conclusion

The intra-conduit negative pressure system is a feasible and promising way to cure urinary fistula following ileal conduit urinary diversion. Because this procedure is a mini-invasive and simple approach, it might represent an alternative in selected patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Cystectomy and urinary diversion are some of the most complicated procedures in urological operations, with a nearly 40% perioperative morbidity rate. The presence of urinary fistula after ileal conduit urinary diversion is rare, but the management of this complication is challenging [1,2,3,4]. Although ureteroenteric anastomosis and conduit closure both carry the risk of urine leakage, management is simple as follows: evaluate and ensure urinary fistula, drain the urine, and then repair the fistula actively or conservatively [4,5,6,7,8]. Compared to surgical approaches, retrograde stent placement and nephrostomy are more common mini-invasive approaches than surgical approaches for addressing the presence of urinary fistula following ileal conduit urinary diversion [8,9,10,11]. A contrastographic study before nephrostomy can be used to comprehensively evaluate abdominal/pelvic ureter and ureterointestinal anastomoses. However, sometimes urine cannot be completely drained, and a balloon is used to obstruct the ureter during nephrostomy. Although completeness has been favorable in recent studies, it is a complicated mini-invasion procedure in clinical practice.

Negative pressure system (NPS) drainage has generally been used to cure complicated wounds [12,13,14]. In a sparse number of reports, NPS drainage has also been revealed as a promising outcome in the management of urinary fistula [15,16,17]. Therefore, we tried to use an intra-conduit NPS as a conservative way to cure patients who had suffered from urine leakage after ileal conduit urinary diversion since 2012. Initially, the NPS was only recommended for patients with good performance as an alternative for retrograde stenting or nephrostomy. We now report our preliminary experiences using the intra-conduit NPS to address the presence of urinary fistula after ileal conduit urinary diversion.

Methods

Patients who underwent ileal conduit urinary diversion in our center were retrospectively reviewed from August 2012 to July 2017. Urine leakage was diagnosed by imaging and/or the amount of abdominal/pelvic drainage reported in drainage creatinine studies. For patients who did not present with significant abdominal infection or other severe morbidities, the intra-conduit negative pressure system was set as the conservative treatment. If this treatment did not work within 2 days, subsequent treatments such as the retrograde placement of ureter stents, nephrostomy or open surgery would be performed. Informed contest was confirmed after a comprehensive consultation.

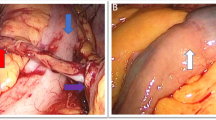

A sterile silicon tube (F18 abdominal drainage tube) with lateral holes was reset into the conduit in patients who had this tube removed after the operation. Then, a mini-plastic tube (F12 stomach tube) with lateral holes was also placed into the silicon tube and was tied to a negative pressure system (Figure 1). During this process, if the ureteral stents had not been previously removed, they were now kept, and the silicon tube was gently placed into the ileal conduit (Additional file 1: Figure S1). When the negative pressure system had a pressure of 20–25 cmH2O, urine was drained out continuously, and the abdominal/pelvic drainage decreased significantly. Most of the time, the NPS was supplied by the central negative pressure system; when the patients were released from the hospital bed, a negative pressure machine with a battery was administered. This process could be accomplished at the bedside and would work for approximately one week, where no urine leakage was detected by clinical evaluation as characterized by the dose of urine, the amount of abdominal drainage, the creatinine drainage level, patient complaints, etc.

The perioperative clinical features were retrospectively analyzed, and the final follow-up was completed in October 2018. Survival status was recorded, and imaging of the upper urinary tract was retrieved during follow-up of patients with primary cancer.

Results

During these 5 years, 446 cases of ileal conduit urinary diversion were completed following radical cystectomy or pelvic exenteration in our center. All ureterointestinal anastomoses were performed using Bricker ureteral implantation, and 18 patients suffered from urine leakage 30 days after this difficult procedure. Of these patients, 13 presented with a high amount of abdominal/pelvic drainage and decreased urine output from the ileal conduit without significantly severe morbidities. An intra-conduit negative pressure system was first chosen as the conservative treatment for these patients.

The median age was 60 years old (42–74 years), and 7patients were male. The primary diagnosis was bladder cancer in 11 patients. The median interval between IC and the diagnosis of urinary fistula was 15 days (2–28 days), and elevated creatinine levels were detected in the abdominal/pelvic drainage with a median level of 2114 μmol/L (636-3852 μmol/L). Abdominal X-ray was performed in 4 patients to identify the locations of the ureteric stents, and abdominal/pelvic contrast-enhanced CT was performed in 2 patients without positive findings. An intravenous pyelogram confirmed 1 ureterointestinal anastomotic fistula, but this method was not used in the first 2 weeks after the operation. Additionally, an ileal conduit contrastographic study confirmed 2 conduit fistulas. When the intra-conduit NPS was used as the primary treatment, a significant decrease in abdominal/pelvic drainage was identified in 12 patients. For these patients, the median time that the NPS was used was9 days (7–11 days), and then the fistula was cured (Table 1).

The other patient showed no improvement after 2 days of observation and then underwent open surgery for the combination of consistent ileus and suspicious abdominal infection. Preoperative contrast imaging showed a significant leak at the location of the distal conduit. During the reoperation, stickiness made it difficult to repair a 1-cm hole linked to the left ureterointestinal anastomosis. During this operation, we found that a sticky belt pressed over the distal third of the ileal conduit, and the silicon tube of the NPS did not cross this stricture to suck urine out completely. Double ureter stents and 2 abdominal drainage tubes were placed, and a new silicon tube was placed to the end of the ileal conduit. No urine leaked into the abdominal/pelvic field, and the patient was cured 9 days after the operation.

With a median follow-up of 22 months (16–46 months), 1 patient died of cervical cancer 41 months after NPS treatment. No hydronephrosis was detected, and no recurrence of fistula occurred.

Discussion

Urinary fistula following ileal conduit urinary diversion is rather rare, but it is associated with severe comorbidities such as abdominal infection, ileus, and metabolism impairment. Treatment is challenging, especially when it is administered following complicated pelvic organ resection and urinary diversion [6, 8, 9]. For these fragile patients, the management of urinary fistula should be as minimally invasive as possible. A surgical approach is usually avoided due to postoperative complications and stickiness. In recent years, several approaches including a retrograde ureteral approach and percutaneous nephrostomy have been developed in the field of endourology to address this complicated consequence, but neither of these two options is easy to accomplish [18,19,20,21].

In this cohort, most (12/13) patients with urinary fistulas following ileal conduit urinary diversion were cured with the intra-conduit NPS, which was a time-consuming (7–11 days) but an extremely simple, safe and mini-invasive method. For these selected patients, the use of the intra-conduit NPS as a conservative treatment was compatible and tolerated, as this bedside process was nearly noninvasive. It was easy to evaluate the effect of the NPS via the decreases in abdominal/pelvic drainage and the normalized creatinine level. For the patient who experienced failure of NPS, we found that the ileal conduit was pressed by a sticky belt during the operation so that the silicon tube could not reach the end of the conduit. This may have resulted in the inability of urine to be successfully and completely suctioned. When the silicon tube was successfully placed during the second operation, the NPS worked efficiently after the operation. In fact, most urine leakage following ileal conduit urinary diversion was due to ureteroenteric anastomosis and conduit closure, so the drainage of urine out of the conduit was critical to cure urine leakage, and the intra-conduit NPS might be a good procedure to accomplish this purpose.

In recent years, an increasing number of studies have demonstrated that endourology approaches are feasible for dealing with upper urinary tract lesions. Olson Land colleagues reported that the success rate was approximately 74%(40/54) during retrograde endourological management of upper urinary tract abnormalities [10]. An antegrade percutaneous flexible endoscopic approach also demonstrated favorable outcomes [11].

In clinical practice, percutaneous nephrostomy is feasible and relatively safe for ureteroenteric anastomosis stricture. However, for patients with urine leakage following ileal conduit urinary diversion, there is often no obstruction of the ureter. Without hydronephrosis, nephrostomy is deemed to be a difficult procedure, and it is not very safe for patients following radical cystectomy/pelvic exenteration and ileal conduit urinary diversion. Therefore, this procedure should be performed only in high-volume centers by experienced surgeons. Retrograde stenting is much safer than nephrostomy, but exploration of the ureteral anastomosis is time-consuming, and mucosal edema of the ileal conduit and ureter makes the procedure difficult. Additionally, this process has a potential risk of invasive abdominal infection.

Compared to endourology approaches and transperitoneal surgery, the intra-conduit NPS is a more mini-invasive and convenient approach [9, 18]. It is a bedside procedure, but we can’t see the details of the conduit during this process, and the placement of the silicon tube might not be deep enough for certain reasons. Additionally, this procedure should be performed by a surgeon who is familiar with the operation details for each patient. If this procedure is not successful, further management, such as ureteral stenting and/or nephrostomy and even surgery might be needed. Moreover, for 8 patients, the ureteral stent was not removed when urinary fistula was diagnosed. Therefore, retrograde ureteral stenting might not be very reliable for some patients.

Although there is no recommendation of the NPS in the treatment of urinary fistula following ileal conduit urinary diversion, the NPS has often been used in complicated wounds, and its uniform negative pressure can enhance wound healing. In some complicated cases of urine leakage, the NPS was associated with a favorable outcome [15, 16]. In this study, the use of the intra-conduit NPS also resulted in a favorable outcome as a conservative procedure. Therefore, the NPS might be a good alternative for curing urinary fistula following ileal conduit urinary diversion. Compared to other approaches, the intra-conduit NPS is a mini-invasive and compatible approach, and caregivers should attempt its use in clinical practice in selected patients.

This retrospective study did not strictly define the indications of the NPS, and selection bias was inevitable because all patients were in good conditions when they chose the intra-conduit NPS as a conservative treatment for urine leakage. In terms of the rarity of urine leakage, the population was limited, and no control group was recorded. As the NPS is a new approach for treating urine leakage following ileal conduit urinary diversion, advanced studies and long-term follow-up periods are needed. All of these patients were reviewed in our single center, a university-affiliated hospital. Furthermore, these patients received good supportive treatment and consistent observation and evaluation. To our knowledge, this is the largest report of the use of the NPS for urinary fistula. As a conservative treatment, the intra-conduit negative pressure system is a mini-invasive and compatible approach for selected patients with urine leakage following ileal conduit urinary diversion.

Conclusion

The intra-conduit negative pressure system is a feasible and promising way to cure urinary fistula following ileal conduit urinary diversion. As this system is a mini-invasive and simple approach, it might represent an alternative for nephrostomy in selected patients. Further advanced studies are needed.

Abbreviations

- IC:

-

Ileal conduit

- NPS:

-

Negative pressure system

References

Novara G, Catto JW, Wilson T, et al. Systematic review and cumulative analysis of perioperative outcomes and complications after robot-assisted radical cystectomy. Eur Urol. 2015;67:376–401.

Bochner BH, Dalbagni G, Sjoberg DD, et al. Comparing open radical cystectomy and robot-assisted laparoscopic radical cystectomy: a randomized clinical trial. Eur Urol. 2015;67:1042–50.

Sathianathen NJ, Kalapara A, Frydenberg M, et al. Robotic assisted radical cystectomy vs open radical cystectomy: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Urol. 2019;201:715–20.

Lee RK, Abol-Enein H, Artibani W, et al. Urinary diversion after radical cystectomy for bladder cancer: options, patient selection, and outcomes. BJU Int. 2014;113:11–23.

Gill HS. Diagnosis and surgical management of uroenteric fistula. Surg Clin North Am. 2016;96:583–92.

Kuetting D, Pieper CC. Percutaneous treatment options of lower urinary tract fistulas and leakages. Rofo. 2018;190:692–700.

Brown KG, Koh CE, Vasilaras A, Eisinger D, Solomon MJ. Clinical algorithms for the diagnosis and management of urological leaks following pelvic exenteration. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2014;40:775–81.

Smith ZL, Johnson SC, Golan S, McGinnis JR, Steinberg GD, Smith ND. Fistulous complications following radical cystectomy for bladder cancer: analysis of a large modern cohort. J Urol. 2018;199:663–8.

Msezane L, Reynolds WS, Mhapsekar R, Gerber G, Steinberg G. Open surgical repair of ureteral strictures and fistulas following radical cystectomy and urinary diversion. J Urol. 2008;179:1428–31.

Olson L, Satherley H, Cleaveland P, et al. Retrograde endourological management of upper urinary tract abnormalities in patients with Ileal conduit urinary diversion: a dual-center experience. J Endourol. 2017;31:841–6.

Stuurman RE, Al-Qahtani SM, Cornu JN, Traxer O. Antegrade percutaneous flexible endoscopic approach for the management of urinary diversion-associated complications. J Endourol. 2013;27:1330–4.

Montori G, Allievi N, Coccolini F, et al. Negative pressure wound therapy versus modified barker vacuum pack as temporary abdominal closure technique for open abdomen management: a four-year experience. BMC Surg. 2017;17(1):86.

Driver VR, Eckert KA, Carter MJ, French MA. Cost-effectiveness of negative pressure wound therapy in patients with many comorbidities and severe wounds of various etiology. Wound Repair Regen. 2016:241041–58.

Glass GE, Murphy GF, Esmaeili A, Lai LM, Nanchahal J. Systematic review of molecular mechanism of action of negative-pressure wound therapy. Br J Surg. 2014;101:1627–36.

Yetisir F, Salman AE, Aygar M, Yaylak F, Aksoy M, Yalcin A. Management of fistula of ileal conduit in open abdomen by intra-condoit negative pressure system. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2014;5:385–8.

Freeman JJ, Storto DL, Berry-Caban CS. Repair of a vesicocutaneous fistula using negative-pressure wound therapy and urinary diversion via a nephrostomy tube. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2013;40:536–8.

Heap S, Mehra S, Tavakoli A, Augustine T, Riad H, Pararajasingam R. Negative pressure wound therapy used to heal complex urinary fistula wounds following renal transplantation into an ileal conduit. Am J Transplant. 2010;10:2370–3.

Asvadi NH, Arellano RS. Transrenal antegrade ureteral occlusion: clinical assessment of indications, technique and outcomes. J Urol. 2015;194:1428–32.

Natarajan V, Boucher NR, Meiring P, Spencer P, Parys BT, Oakley NE, Stent (Society for Endourology in North Trent) Group. Ureteric embolization: an alternative treatment strategy for urinary fistulae complicating advanced pelvic malignancy. BJU Int. 2007;99:147–9.

Horenblas S, Kroger R, van Boven E, Meinhardt W, Newling DW. Use of balloon catheters for ureteral occlusion in urinary leakage. Eur Urol. 2000;38:613–7.

Forde JC, O'Connor KM, Fanning DM, Guiney MJ, Lynch TH. Management of a persistent ileo-ureteric anastomotic leak with bilateral ureteric occlusion using angioplasty balloon catheters. Can J Urol. 2010;17:5397–400.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZKQ, YLY, XZ: Protocol/project development; HTL, LT, XZ, KHX: Data collection or management; YLY, HTL, LT, XZ, DX: Data analysis; YLY, ZKQ, HTL, DX, LT: Manuscript writing. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center (YP2008063). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Consent to participate was acquired in written format.

Consent for publication

not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

The installation of negative pressure system

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Ye, Yl., Liang, Ht., Tan, L. et al. Conservative treatment for urinary fistula following ileal conduit urinary diversion: a simple method. BMC Urol 19, 131 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12894-019-0564-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12894-019-0564-3