Abstract

Background

To improve the understanding of acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia (AFOP), we present one case of AFOP proven by percutaneous lung biopsy along with clinical features, chest imaging and pathology.

Case presentation

A 50-year-old man was admitted to our department after he was given empiric therapy for community-acquired pneumonia (CAP). The clinical symptoms of the patient were dry cough, chills, night sweats and high fevers. Chest computed tomography (CT) scan showed a high-density shadow in the right lung lobe, similar to lobular pneumonia. The patient was preliminarily diagnosed with community-acquired pneumonia; however, antibacterial treatment was ineffective. To confirm the diagnosis, we performed bronchoscopy and percutaneous lung biopsy; pathology was consistent with AFOP. After he was treated with glucocorticoids, the patient’s symptoms were relieved, and the shadow seen on imaging dissipated during the follow-up period.

Conclusions

AFOP is a rare histopathological diagnosis that can be easily misdiagnosed. Clinicians need to consider the possibility of AFOP in the case of invalid antibacterial therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Ever since the concept of AFOP was proposed by Beasley in a pathologic study of 17 patients with acute/subacute lung injury in 2002 [1], more and more cases have been published across all age groups. However, AFOP has not been included in the clinical category of idiopathic interstitial pneumonia (IIP) but has been referred to as a rare pathological type in recent years [2]. Interestingly, AFOP symptoms are not typical; patients commonly present with dyspnoea, cough, fever, etc., which makes it more difficult to diagnose compared to other diseases [1, 3, 4]. In addition, the treatment of AFOP is controversial; both glucocorticoids and immunosuppressive agents have been shown to be effective [1, 3, 4]. To improve the understanding of AFOP, we herein present one case of a patient with AFOP proven by pathology, whose clinical symptoms were significantly relieved by glucocorticoid treatment.

Case presentation

General information

A 50-year-old male farmer, a declared nonsmoker, with history of contact with glyphosate (a kind of herbicide) 2 days prior to symptom onset, was admitted to our department with a 20-day history of dry cough, chills, night sweats and high fevers on October 6. He was administered empiric therapy for community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) with piperacillin-tazobactam and treatment was invalid at a local hospital.

Physical examination

On his admission, vital signs were as follows: temperature, 40 °C, oxygen saturation on room air, 95%. Chest auscultation revealed breath sounds with fine crackles and wheezes increased in the right lung; no other findings were remarkable.

Auxiliary examination

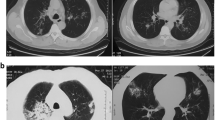

The local hospital chest CT (Fig. 1) showed patchy opacities and a spot-like high density shadow in the right basement of the lower lobe and the right middle lobe. The initial bloodwork was as follows: WBC19.2 × 109/L, N85%, L8%. The procalcitonin level was 1.22 ng/ml, ESR was 72 mm/h. The other laboratory tests all were negative, including rapid antigen tests for influenza and HIV; liver, kidney and coagulation function tests; arterial blood gas analysis; autoimmune and tumour biomarkers; G-test and lipopolysaccharide; blood, bone marrow and sputum culture; and detection of herbicide toxicity.

Preliminary diagnosis: community-acquired pneumonia.

Treatment course

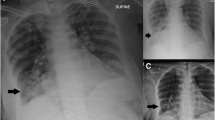

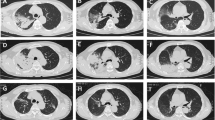

On admission, considering drug-resistant pneumonia, the patient was treated empirically with levofloxacin plus imipenem/cilastatin, imipenem/cilastatin plus vancomycin and anti-tuberculosis treatment in succession; however, symptoms were without remission. Bronchoscopy was conducted, and staining for acid-fast bacillus and fungus was negative in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF), but the pathology study showed (Fig. 2a) massive cellulose exudate under the microscope. Chest CT scan (Fig. 3) showed no improvement, same as before. In view of the situation of invalid antibacterial treatment and exclusion of other infection diseases, the patient was administered methylprednisolone 80 mg daily; the patient’s fever subsided and symptoms improved significantly. To confirm the diagnosis, we conducted an ultrasound-guided percutaneous needle lung biopsy; pathology revealed (Fig. 2b) massive cellulose exudate with organization in the alveolar cavity, alveolar septum widened with oedema and lymphocytes and sparse eosinophilic infiltration. No necrosis, bleeding or neutrophil infiltration could be seen. Above all, we considered a diagnosis of AFOP; the patient was continued on methylprednisolone 80 mg daily without obvious discomfort. After 5 days, the dose was changed to 40 mg daily. Repeat chest CT scan (Fig. 4) revealed the opacity had reduced in size. After another 3 days, the patient was switched to prednisone 40 mg orally, with a reduction of 5 mg weekly after discharge from our hospital. During the follow-up period, repeat chest CT scan (Fig. 5) showed resolution was achieved and the patient remained asymptomatic.

Haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain, massive cellulose (arrow) exudate with organization in the alveolar spaces, alveolar septum widened with oedema and lymphocytes and sparse eosinophilic infiltration. No necrosis, bleeding or neutrophil infiltration could be seen. a bronchoscopy (original magnification × 10). b ultrasound-guided percutaneous needle lung biopsy (original magnification × 20)

Final diagnosis: acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia (AFOP).

Discussion and conclusions

A literature review revealed that fewer than 120 cases have been published; whether AFOP can be treated as an independent disease or whether it was a distinct pattern of acute lung injury (ALI) remained to be elucidated.

To the best of our knowledge, AFOP diagnosis depends mainly on pathology. The differential diagnosis includes as follows, organizing pneumonia (OP), eosinophil pneumonia (EP), and diffuse alveolar damage (DAD) [5, 6]. Interestingly, AFOP has distinctive histopathology, characterized by massive cellulose exudate with organization in the alveolar spaces, rather than the fibrous tissue and fibroblast proliferation seen in OP; the numerous eosinophils, macrophage infiltration and eosinophil abscesses formed in EP; or the hyaline membranes seen in DAD [5, 6]. Some scholars have suggested AFOP might be the late pathologic changes of ALI, associated with alveolar wall capillary damage and bleeding [7].

AFOP could be idiopathic or could also be associated with other diseases, lung transplantation [8], connective tissue disease [9, 10], infection [11, 12], drug reactions [13], etc. For this case, the patient was a general farmer with a history of contact with an herbicide prior to symptom onset. As a result, could we boldly speculate the pesticide was also an independent risk factor? Glyphosate is similar to paraquat, which is widely used in China’s rural areas. As a low-toxicity herbicide, only a few poisoning cases have been reported [14]. Although glyphosate may not cause pulmonary fibrosis as severe as paraquat, it still might lead to lung injury, including multi-organ damage. Of course, our speculation was done to only improve the understanding of AFOP; the relevant mechanisms need to be further clarified via experiments.

In conclusion, AFOP, which is referred to as a rare histopathological type, can easily be misdiagnosed. Clinicians need to take into consideration the possibility of AFOP in the case of invalid antibacterial therapy. This case was not novel but of significant clinical importance and very instructive.

Abbreviations

- AFOP:

-

Acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia

- ALI:

-

Acute lung injury

- CAP:

-

Community-acquired pneumonia

- DAD:

-

Diffuse alveolar damage

- EP:

-

Eosinophil pneumonia

- H&E:

-

Haematoxylin and eosin

- OP:

-

Organizing pneumonia

References

Beasley MB, Franks TJ, Galvin JR, Gochuico B, Travis WD. Acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia: a histological pattern of lung injury and possible variant of diffuse alveolar damage. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2002;126(9):1064–70.

Travis WD, Costabel U, Hansell DM, King TJ, Lynch DA, Nicholson AG, Ryerson CJ, Ryu JH, Selman M, Wells AU, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: update of the international multidisciplinary classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(6):733–48.

Dai JH, Li H, Shen W, Miao LY, Xiao YL, Huang M, Cao MS, Wang Y, Zhu B, Meng FQ, et al. Clinical and radiological profile of acute Fibrinous and organizing pneumonia: a retrospective study. Chin Med J. 2015;128(20):2701–6.

Gomes R, Padrao E, Dabo H, Soares PF, Mota P, Melo N, Jesus JM, Cunha R, Guimaraes S, Souto MC, et al. Acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia: a report of 13 cases in a tertiary university hospital. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(27):e4073.

Kligerman SJ, Franks TJ, Galvin JR. From the radiologic pathology archives: organization and fibrosis as a response to lung injury in diffuse alveolar damage, organizing pneumonia, and acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia. Radiographics. 2013;33(7):1951–75.

Hashisako M, Fukuoka J. Pathology of idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Clin Med Insights Circ Respir Pulm Med. 2015;9(Suppl 1):123–33.

Cincotta DR, Sebire NJ, Lim E, Peters MJ. Fatal acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia in an infant: the histopathologic variability of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2007;8(4):378–82.

Paraskeva M, McLean C, Ellis S, Bailey M, Williams T, Levvey B, Snell GI, Westall GP. Acute fibrinoid organizing pneumonia after lung transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187(12):1360–8.

Valim V, Rocha RH, Couto RB, Paixao TS, Serrano EV. Acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia and undifferentiated connective tissue disease: a case report. Case Rep Rheumatol. 2012;2012:549298.

Fasanya A, Gandhi V, DiCarlo C, Thirumala R. Acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia in a patient with Sjogren's syndrome. Respir Med Case Rep. 2017;20:28–30.

Chiu KY, Li JG, Gu YY. A case report of acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia with pneumothorax and avian exposure history. Clin Respir J. 2016; doi:10.1111/crj.12553.

Otto C, Huzly D, Kemna L, Huttel A, Benk C, Rieg S, Ploenes T, Werner M, Kayser G. Acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia associated with influenza a/H1N1 pneumonia after lung transplantation. BMC Pulm Med. 2013;13:30.

Piciucchi S, Dubini A, Tomassetti S, Casoni G, Ravaglia C, Poletti V. A case of amiodarone-induced acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia mimicking mesothelioma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191(1):104–6.

Kamijo Y, Takai M, Sakamoto T. A multicenter retrospective survey of poisoning after ingestion of herbicides containing glyphosate potassium salt or other glyphosate salts in Japan. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2016;54(2):147–51.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable as no funds were procured or used for the purpose of any research or manuscript writing related to this case report.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors participated in the care of this patient. SSC and HZ drafted the text and completed research on the supporting and background data. LLY contributed by writing and editing the manuscript. BT, ZKX and SSF helped to guide diagnosis and treatment. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Authors’ information

Shengsong Chen, Hong Zhou and Lingling Yu are resident physicians-in-training, and Bo Tong, Zuke Xiao and Sisi Fan are attending specialist physicians who dedicate their time to mentoring trainees.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient to participate in this case report.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent for publication of clinical details and clinical images was obtained from the patient. A copy of the consent form is available for review by the Editor of the journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.