Abstract

We demonstrate how the latest generation of hybrid pixel detectors of the Timepix family can be used to reconstruct 3 dimensional particle tracks on a microscopic scale, additionally determining the stopping power along the particles’ paths. In an experiment, a Timepix3 detector with a 2 mm thick planar CdTe sensor was irradiated in a 40 GeV/c pion beam and used in a similar way to a time-projection chamber: The coordinates x and y were given by the trajectory projection (pixel pitch: \(55\,\upmu \hbox {m}\)), the z-coordinate was reconstructed from the charge carrier drift time measurement (time binning: 1.5625 ns). The achievable z-resolution was studied at different bias voltages. Systematic inaccuracies due to an imprecise drift time model were determined and separated from the intrinsic uncertainty given by the time resolution. It was shown that a z-resolution of \(60\,\upmu \hbox {m}\) could be achieved by a perfect modeling of the drift time. With the presented z-reconstruction methodology, we studied the charge collection efficiency as a function of interaction depth, which was then used to apply a charge loss correction to the per-pixel energy measurements. 3D event displays of pion, muon and electron tracks are shown.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Early attempts to use pixelated detectors of Medipix/Timepix type for particle tracking were based purely on the analysis of the morphologic characteristics of 2D projections in the xy-plane. The z-coordinate was determined by the entry and exit points, whereby the track broadening due to charge sharing gave further information about track orientation [1]. Later, Filipenko et al. [2] have shown that Timepix can be used similarly to a Time Projection Chamber (TPC) for a 3D track reconstruction. Using a 1 mm thick CdTe at very low reverse bias of \(-\,\,80\,\hbox {V}\), they achieved a z-resolution of \(60\,\upmu \hbox {m}\) (while the resolution in x and y was given by the pixel pitch of \(110\,\upmu \hbox {m}\)). Turecek et al. [3], Pacifico et al. [4], and Bergmann et al. [5] demonstrated and investigated the 3D track reconstruction capability of the latest generation of hybrid pixel detectors of the Medipix collaborations, Timepix3 [6], when used with a highly resistive planar silicon sensor. The latter has shown that a z-resolution of \(29\,\upmu \hbox {m}\) can be achieved with a \(500\,\upmu \hbox {m}\) thick silicon sensor layer at a bias voltage of 130 V.

Compared with the typically gas-filled TPCs, Timepix detectors profit from the advantages of the semiconductor material, such as the higher density (by two orders of magnitude) and the approximately \(10\,\times \) lower energy needed to create free charge carriers, leading to the possibility to reduce the device dimension while providing precise spectroscopic information about the ionizing energy losses in the sensor. Compact semiconductor devices are typically also superior due to the significantly lower drift times giving an increased speed of operation.

Timepix particle trackers are compact, lightweight, portable and easy to use. They can be used in places where the available space is limited, and in situations where weight or power consumption matters. Such applications include space weather analyses [7], the determination of trapped particle directions in the Van-Allen radiation belts [8, 9], monitoring of secondary radiation in hadron therapy [10], the study of the antiproton annihilation [4] and electron microscopy [11]. Especially, when equipped with CdTe or CdZnTe as sensor material Timepix detectors can be investigated for double beta decay experiments [12]. All of the above applications would profit significantly from a determination of the interaction depth in the sensor by improving particle discrimination, background event suppression, annihilation vertex reconstruction, impact angle or impact point determination. A practical example of improved particle discrimination is the characterization of mixed electron-photon radiation fields. Whereas in the 2D projections, electron and photon interactions are indistinguishable, 3D track reconstruction could provide means of separating them. Since photons have to be converted to electrons, photons generate tracks at random depths within the sensor. Electrons however are seen directly upon entering the sensitive volume. Besides, 3D particle tracking clearly allows a separation of penetrating and stopped particles.

In the presented work, we continue methodological development by systematically investigating the track reconstruction capabilities of a Timepix3 with a 2 mm thick CdTe sensor layer at different bias voltages. We show a 3D view of particle interactions seen in a 40 GeV/c pion beam at the Super-Proton-Synchrotron (SPS) at CERNFootnote 1 and illustrate the signatures of different types of interactions.

2 Timepix3

2.1 Basic facts

Timepix3 is the latest generation of hybrid pixel detectors of the Timepix family. A Timepix3 assembly consists of a sensor layer, which is bump bonded to the readout ASIC by the flip-chip technology. In the presented work, a 2 mm thick CdTe sensor was used. This layer is divided into a square matrix of \(256 \times 256\) pixels. The pixel pitch (pixel-to-pixel distance) is \(55\,\upmu \hbox {m}\) thus forming a sensitive area of \(1.98\,\hbox {cm}^{2}\). The assembly, its readout (AdvaDAQ [3]) and the per-pixel energy calibration coefficients were provided by ADVACAM s.r.o.Footnote 2 In contrast to its predecessor Timepix [13], Timepix3 allows the measurement of the time of an interaction (time-of-arrival) and energy deposition (by the time-over-threshold) simultaneously in each individual pixel. It provides a data-driven readout scheme, i.e. that only the pixel registering an interaction is read out. The per-pixel dead time is about 475 ns. The maximal achievable hit rate is \(40\,\hbox {Mpixel cm}^{-2}\ \hbox {s}^{-1}\).

2.2 Charge carrier motion

Ionizing radiation interacting in the sensor creates free charge carriers (electrons e and holes h), whose number is proportional to the amount of energy deposited in the sensor material. These charge carriers begin to drift through the sensor material due to an applied potential difference between the common back-side contact (cathode) and the pixelated anode, the so-called bias voltage \(U_{\mathrm{bias}}\).

The drift velocity \(\mathbf {v}_{e,h}\) of electrons and holes, respectively, is directly proportional to the electric field:

whereby the proportional constant \(\upmu _{\mathrm{e,h}}\) is called the mobility. In CdTe, typical mobilities are: \(\upmu _{\mathrm{e}} = 1050\,\hbox {cm}^{2}\hbox {V}^{-1}\hbox {s}^{-1}\) and \(\upmu _{\mathrm{h}} = 100\,\hbox {cm}^{2}\hbox {V}^{-1}\hbox {s}^{-1}\) [14]. Due to variations in CdTe production, electric field profiles in CdTe sensors can differ from sample to sample. In [15], it was shown that the overall trend of the electric field in sensors with an ohmic contact is linearly decreasing with increasing z.

In the presented study, the electric field in z-direction E(z) was found to be best described by:

where \(d = 2\,\hbox {mm}\) is the sensor thickness. The parameters \(f_{1} = 0.06 \pm 0.01\) and \(f_{2} = (-\,30.15 \pm 3.0)\,\hbox {V}\) were determined by comparison with the measured drift times (see Sect. 5.3).

A lateral broadening of the initially created charge cloud is caused by diffusion and repulsion [16,17,18,19]. It increases with increasing drift time, thus also with the distance to the pixel electrodes z, and, in the case of repulsion, with higher energy deposition. During the drift motions, charge carriers can recombine, so that the amount of induced charge is reduced.

2.3 Charge induction

While drifting in the sensor, the charge carriers induce mirror charges in the pixel electrodes. For modeling the induction process the concept of the so-called weighting potential \(\varPhi \) was introduced [20, 21]. It is defined as the potential that would exist in the detector with the collecting electrode held at unit potential, while holding all other electrodes at zero potential [22]. Its shape mainly depends on the geometry of the sensor and electrodes. Figure 1 shows the weighting potential \(\varPhi (z)\) for the geometry of the assembly used in the presented work. It was calculated by numerically solving Eq. (16) in [23] using \(N=1000\), \(w_{\mathrm{x}} = w_{\mathrm{y}} = 55 \,\upmu \hbox {m}\) (pixel pitch), \(d = 2000\,\upmu \hbox {m}\) (sensor thickness) and \(x = y = 0\) (weighting potential at the center of the electrode pads). The charge induced at the time \(t_{\mathrm{drift}}\) is then given by:

where \(z_{0}\) is the location at which the charge \(Q_{0}\) was created. Due to the small pixel size to sensor thickness ratio, the major contribution to the measured (induced) signal is created when the charge carriers are in close vicinity of the pixel electrodes, which is known as the small-pixel effect.

2.4 Per-pixel signal processing

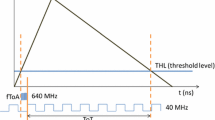

Figure 2 schematically illustrates the Timepix3 pixel electronics and the signal processing. In each pixel, the induced current is converted to a voltage pulse and amplified. The charge-sensitive amplifier output is then compared to a globally set threshold level (THL), which was set at 2.52 keV in the presented measurements. If the pulse exceeds the THL, the time-over-threshold (ToT) and the time-of-arrival (ToA) are determined in the following ways:

-

The ToT is the time interval the voltage pulse is above the THL. This interval is sampled with a 40 MHz clock. Energy calibration is done pixel by pixel with X-rays of known energy;

-

The ToA is determined by the time when the signal crosses the THL on its upward slope. A continuously running clock of 40 MHz determines the base ToA value. To increase precision, an additional 640 MHz clock from a ring oscillator is used to sample the time of the THL crossing to the next rising edge of the base ToA clock. This way, a time binning of 1.5625 ns is achieved.

Schematic illustration of the Timepix3 pixel electronics and signal processing chain. Two concurrent signal of different energy depositions are shown. The induced current at the input pad is shaped by the charge sensitive amplifier. The constant rise time of the preamplifier output pulse leads to the so-called time-walk effect

3 Reconstruction principles

In order to perform a 3D reconstruction of particle tracks, Timepix3 is used similarly to a TPC [5]. The crucial point of the reconstruction principle is thus the understanding of the measured “drift” times \(t_{\mathrm{drift,meas}.}\) in each pixel as a function of the interaction depth z. The drift time measured in pixel i is hereby given by the difference of the pixel’s time stamp \(t_{i}\) and the minimal time within the set of pixels forming a track \(t_{\mathrm{min, track}}\).

Due to charge induction, pulse shaping in the charge-sensitive amplifier already starts before the charge carriers actually arrive at the collecting pixel electrodes. We refer to the time when the pulse shaping starts as \(t_{\mathrm{induction}}\). The duration from the start of the pulse shaping to the time when the hit is assigned is approximated by an offset \(t_{\mathrm{offset}}\) and, for low energy deposition, the delay due to time-walk \(t_{\mathrm{time-walk}}\). Figure 3 illustratively summarizes the situation.

Whereas \(t_{\mathrm{induction}}\) is given by physics of the charge transport in the sensor and induction at the pixel electrodes, \(t_{\mathrm{offset}}\) and \(t_{\mathrm{time-walk}}\) depend on the response of the analogue part of the pixel electronics. As described in [5] and Sect. 3.1, \(t_{\mathrm{time-walk}}\) can be corrected for. \(t_{\mathrm{offset}}\) was assumed to be the same constant delay in each pixel (the same assumption was made in [2]). Since the reconstruction method is based on measuring the time differences within the set of pixels forming a track, this offset is canceled out and does not play a role for the z-reconstruction.

The important parameter for z-determination is thus \(t_{\mathrm{induction}}\). In Sect. 3.2, it is shown, that \(t_{\mathrm{induction}}\) depends on the interaction depth z and deposited energy \(E_{\mathrm{dep}}\). To properly determine the z-coordinate from the measured data, we thus calculated 2D look-up tables \(z_{\mathrm{look-up}}(t_{\mathrm{induction}},E_{\mathrm{dep}})\) describing the dependence of z not only on \(t_{\mathrm{induction}}\), but also on deposited energy \(E_{\mathrm{dep}}\).

The z-coordinate in pixel i was then reconstructed in the following way:

-

1.

Evaluate the “rough” z-coordinate:

$$\begin{aligned} z_{ \mathrm{rough}, i} = z_{\mathrm{look-up}} \left( t_{i} - t_{\mathrm{min, track}}, E_{\mathrm{meas},i} \right) , \end{aligned}$$(5)where \(E_{\mathrm{meas},i}\) is the measured pixel energy deposition.

-

2.

Correct for possible charge losses by dividing \(E_{\mathrm{meas},i}\) by the charge collection efficiency \(\varepsilon _{cc}(z)\):

$$\begin{aligned} E_{ \mathrm{corrected}, i} = \frac{ E_{\mathrm{meas},i}}{\varepsilon _{cc} \left( z_{ \mathrm{rough}, i} \right) }. \end{aligned}$$(6)\(\varepsilon _{cc}(z)\) was determined from the experimental data as described in Sect. 5.5.

-

3.

Re-evaluate the z-coordinate using the corrected energy \(E_{\mathrm{corrected},i}\):

$$\begin{aligned} z_{ \mathrm{rec.}, i} = z_{\mathrm{look-up}} \left( t_{i} - t_{\mathrm{min, track}}, E_{\mathrm{corrected},i} \right) . \end{aligned}$$(7)

Even though, strictly speaking, the quantity used for z-reconstruction \(t_{\mathrm{induction}}\) is not the time the charge carriers need to reach the pixel electrodes from their position of origin \(t_{\mathrm{drift}}\) (see Fig. 3), both quantities are in close relation. For reasons of vividness and consistency with the notations used in other works [4, 5] we prefer to use the term drift time \(t_{\mathrm{drift}}\) throughout the presented work.

3.1 Time-walk correction

The so-called time-walk effect describes the later detection of pulses with low amplitude (low energy) when compared to concurrent signals of higher amplitudes, as schematically depicted in Fig. 2. This is caused by the constant rise times of the voltage pulses after the preamplifier in combination with the comparison of the pulse to a threshold level. For proper time-stamping, the time-walk effect has to be corrected for. This can be done by test pulses [24] or experimentally [3, 5]. In the presented work, the latter method was used. Therefore, the sensor was irradiated with 59.6 keV photons from a \(^{241}\)Am-source. In the data, 4-pixel clusters with one of their pixels measuring an energy in the range from 30 to 32 keV were selected. A typical 4-pixel event is shown in Fig. 4.

a Scatter plot of delays due to the time-walk effect in dependence of the energy of pixels in a 4-pixel cluster with one pixel measuring 30–32 keV. The detector was irradiated by 59.6 keV \(\gamma \)-rays; b delay due to time-walk as a function of energy measured in the pixels. The subtraction of the value calculated for the pixel energy according to the fit curve corrects for the time-walk. The fit is given by the red line in a

The pixel with the 30–32 keV measurement determines the reference time stamp \(t_{\mathrm{ref}}\). For each of the 3 other pixels, the delay due to the time-walk \(t_{i, \mathrm time-walk}\) is obtained by subtracting the pixel’s time stamp from the reference time: \(t_{i,\mathrm time-walk} = t_{i} - t_{\mathrm{ref}}\).

Figure 5a shows the scatter plot of measured pixel energies \(E_{i}\) versus their time delays \(t_{i, \mathrm time-walk}\) for 14,480 4-pixel cluster events. The width of the time-delay distributions increases for energies closer to the threshold since fluctuations of the THL have a bigger effect on the measurement of the THL crossing when the slopes are less steep.

To obtain the time-walk correction function, the medians of the time delay distributions for each energy channel are calculated and fitted by the function (see Fig. 5b)

Fixing the value of parameter c to 1, we find \(a = (129.0 \pm 1.4)\,\mathrm{ns} \times \mathrm{keV}\), \(b = (0.14 \pm 0.04) \,\mathrm{keV}\), and \(d = (-\,5.41 \pm 0.08)\) ns. The time-walk corrected time \(t_{i, \mathrm corr.}\) in each pixel i is then given by:

3.2 Modeling the time of induction

To understand the contribution of the charge induction process to the time measurement, the time dependence of the induced charge at the collecting pixel electrodes was calculated. Iteratively, the energy equivalent charge \(Q_{0}\), created at interaction depth \(z_{0}\) and time \(t_{0} = 0\), was drifted through the sensor volume. In each iteration i, the absolute time \(t_{i}\) was increased by \(\varDelta t = 0.3\,\hbox {ns}\) (\(t_{i} = t_{i-1} + \varDelta t\)). The positions of electrons \(z_{\mathrm{e}}(t_{i})\) and holes \(z_{\mathrm{h}} (t_{i})\) were calculated using Eqs. 1 and 2, respectively, with the electric field from Eq. 3. Since the z-differences are small, the electric field could be approximated by a constant, without significant loss of precision. The induced charge \(Q_{i}\) is given by the sum of the charges induced by electrons \(Q_{e, i}\) and holes \(Q_{h, i}\). Both quantities were calculated according to Eq. 4.

Figure 6 illustrates the calculated temporal behavior of the induced charge at the pixel electrodes for different interaction depths and energy depositions at a bias voltage of \(-\,\,100\,\,\hbox {V}\).

We now define \(t_{\mathrm{induction}}\) as the time when the induced charge reaches the THL level of 2.52 keV. As seen in Fig. 6, this means that higher energy deposition results in earlier hit assignment. Since the experimental approach for time-walk correction (see Sect. 3.1) was chosen, the time delays due to the induction process are automatically compensated for in the energy range below 30 keV. Thus, for look-up table calculation the energy range from 30 keV to 1 MeV was sufficient. An energy binning of 25 keV (giving a maximal uncertainty of \(10\,\upmu \hbox {m}\)) and a time binning of 0.3 ns (significantly below the Timepix3 time granularity) was used.

4 Experimental setup

Experiments were performed at SPS at CERN. A Timepix3 with a 2 mm thick CdTe sensor was placed at angle \(45\,^{\circ }\) with respect to the sensor normal in a 40 GeV/c pion beam. The assembly had an ohmic contacting scheme. A schematic top view and illustrative picture of the setup are shown in Fig. 7. The Timepix3 detector with the AdvaDAQ readout was connected to a USB3 port of the control PC, which was used to remotely start and stop the data acquisition. During measurements, the temperature of the sensor was stabilized at values between 30 and \(35^{\circ }\hbox {C}\) by passive cooling. In this temperature range, typical leakage currents were well below \(10\,\upmu \hbox {A}\). Investigations were carried out at different bias voltages in the range from \(-\,\,100\) to \(-\,\,500\,\,\,\hbox {V}\).

Measurement setup: illustrative view (a) and picture (b) of the detector arrangement at the beam line. The Timepix3 assembly sits on top of the AdvaDAQ readout which is connected through a USB cable to the control PC. A remotely controllable stepper motor with \(\upmu \hbox {m}\) precision was used to adjust the device at different angles in the beam

Detector response in the form of the 2D projections of ToT and relative ToA (within a track). The first 100 events of the measurement at \(-\,\,200\,\,\,\hbox {V}\) bias are shown. The color scale in the left figure represents the per-pixel energy deposition. In the right figure, it gives the relative time difference within a single track

The spectroscopic pixel information (left) and the relative time (right) within a 40 GeV/c pion track. The time-walk correction described in Sect. 3.1 was applied to the data. The bias was set at \(-\,\,100\,\hbox {V}\)

5 Data analysis

In the following section, measured data are utilized to determine the z-dependence on drift time, achievable z-resolutions, and the depth dependent charge collection efficiency \(\varepsilon _{\mathrm{cc}}\).

The detector response in the form of the 2D projections of energy and time measurements is shown for an illustrative set of 100 detected particle tracks in Fig. 8. For further analysis, each individual event is analyzed separately.

5.1 Typical pion event

Figure 9 illustrates the detector response to a typical pion track passing through the sensor layer in the form of the per-pixel energy deposit (ToT) and the relative time differences (\(\varDelta \hbox {ToA}\)). The bias was set at \(-\,\,100\,\hbox {V}\).

The temporal profile, which is related to the charge carrier drift time \(t_{\mathrm{drift}}\) (see discussion in Sect. 3), increases almost linearly when following the particle trajectory. Higher time differences correlate with greater distances to the pixel electrodes. The energy depositions along the particle trajectory show a systematic decrease towards higher distances to the pixel electrodes. At greater distances, drift times are longer and the amount of material to be traversed by the charge carriers is bigger. This gives rise to charge carrier losses, for example due to recombination in trapping centres (e.g. crystal lattice defects). The charge collection (induction) efficiency \(\epsilon _{\mathrm{cc}}\) is thus lower at greater distance z to the pixel contact.

5.2 Principles of data evaluation

For the following analyses a statistical approach was used. To achieve a clean data set of pion tracks without \(\delta \)-rays, clusters were filtered by their morphological characteristics: Tracks of interest were tracks fitting into a rectangular box with given width (\(\varDelta x\)) and height (\(\varDelta y\)) (for illustration see Fig. 10). Due to higher charge sharing for the measurements at lower bias, different ranges of allowed box dimensions were used for the different bias voltages investigated. Furthermore, tracks with contact to the edges were omitted.

Table 1 gives the cut ranges and shows the amount of remaining tracks, which were then analyzed in the following way:

-

1.

The energy weighted coordinate \(y_{\mathrm{mean}}\), the minimal drift time \(t_{\mathrm{drift}}\), and the total energy \(E_{\mathrm{tot}}\) were calculated for each column x.

-

2.

The entrance \(\mathbf {x}_{\mathrm{entry}} = (x_{\mathrm{entry}}, y_{\mathrm{mean, entry}})\) and exit \(\mathbf {x}_{\mathrm{exit}} = (x_{\mathrm{exit}}, y_{\mathrm{mean, exit}})\) points were determined from these average coordinates. The entry point is defined as the point at \(z = d\), the exit point is the point at \(z = 0\,\hbox {mm}\). The latter was determined in the same way as described in [5].

-

3.

Linear interpolation between \(\mathbf {x}_{\mathrm{entry}}\) and \(\mathbf {x}_{\mathrm{exit}}\) then yields the reference interaction depths:

$$\begin{aligned} z_{\mathrm{geo.}}(r_{xy}) = \frac{d}{L_{xy}} \times r_{xy}, \end{aligned}$$(10)along the trajectory, where \(r_{xy} = |\mathbf {x} - \mathbf {x}_{\mathrm{entry}}|\) is the projected distance of point \(\mathbf {x}\) along the particle trajectory and \(L_{xy} = |\mathbf {x}_{\mathrm{exit}}-\mathbf {x}_{\mathrm{entry}}|\) the projected track length. Charge sharing has been taken into account by subtracting half of the track width from its length.

Interaction depths z as a function of the drift time \(t_{\mathrm{drift}}\). Lines indicate the prediction according to the model derived in Sect. 3.2

5.3 z-dependence on drift time

Figure 11 shows the z-dependence on drift time. Therefore, the drift times were put to 32 equally distant depth of interaction bins. The lines indicate the behavior expected from the model derived in Sect. 3.2 for the energy bin 30–55 keV (corresponding to the average energy measured in the pixels). Overall, good agreement was found. At \(-\,\,200\,\,\,\hbox {V}\) and \(-\,\,100\,\,\hbox {V}\) deviations are observed. Possible explanations for the deviations are given in Sect. 5.4.

5.4 z-resolution

To determine the achievable z-resolution, \(z_{\mathrm{rec.}}\) was determined as described in Sect. 3 and compared to \(z_{\mathrm{geo.}}\). The comparison is shown for an event from the measurement at bias \(-\,\,100\,\hbox {V}\) in Fig. 12. Here, the dispersion of the differences \(\varDelta z = z_{\mathrm{rec.}} - z_{\mathrm{geo.}}\) can be described by a gaussian with a \(\sigma _{\mathrm{z}}\) of \(45.3\,\upmu \hbox {m}\).

To study the depth dependence of the z-resolution, the differences \(\varDelta z\) were determined and sorted into 32 equally distant interaction depth bins. In each bin, the \(\varDelta z\) distribution was fitted by a gaussian.

The gaussian mean deviations \(\langle \varDelta z \rangle \) are shown as a function of z in Fig. 13a. They can be interpreted as the systematic errors arising from the inaccuracy of the drift time model. The smallest deviations (\(\langle \varDelta z \rangle < 50\,\,\upmu \hbox {m}\)) were found in the measurements at bias voltages of \(-\,\,300\,\,\,\hbox {V}\), \(-\,\,\,\,400\,\,\,\hbox {V}\) and \(-\,\,\,\,500\,\,\,\hbox {V}\). At bias voltages of \(-\,\,200\,\,\,\hbox {V}\) and \(-\,\,100\,\,\,\hbox {V}\), they are below \(63\,\upmu \hbox {m}\) and \(83\,\upmu \hbox {m}\), respectively. Systematic uncertainties could be due to inaccuracies of the electric field model and simplifications made for the amplifier response. They can be reduced or eliminated by an improved drift time model.

The gaussian widths \(\sigma _{z}\), shown in Fig. 13b, are related to the granularity of the drift time measurements. Given that drift times are lower at lower absolute values of bias voltages, sampling errors due to the time-granularity should be smaller. Overall, the expected behavior was found. However, there is no significant difference between the measurements at \(-\,\,400\,\hbox {V}\) and \(-\,\,500\,\hbox {V}\). Additionally, at intermediate z-values, \(\sigma _{z}\) is higher at bias \(-\,\,100\,\hbox {V}\) than at bias \(-\,\,200\,\hbox {V}\). This indicates that other effects contribute. These could be variations of the time-walk correction parameters between individual pixels or local changes of drift times, e.g. due to inhomogeneities in the electric field.

Table 2 gives an overview of the experimentally determined maximal z-resolutions and the ranges of the systematic deviations.

Event display of a 40 GeV/c pion track with outgoing \(\delta \)-ray. The bias voltage was set at \(-\,\,100\,\,\,\hbox {V}\). The primary pion passed through the sensor volume almost undeflected. The \(\delta \)-ray is characterized by a curly track due to multiple scattering along its path. Pion and \(\delta \)-ray tracks are labeled. For pion trajectory determination an iterative 3D Hough line tranform was used. The result is indicated by a dashed line. The energy depositions in each “voxel” are encoded by color and the size of the points. The projection in the xy-plane depicts the z-coordinate in gray scale. The sensitive volume was cropped to the region of interest and relative coordinates were calculated

Same as Fig. 15, but measured at the bias voltages \(-\,200\,\hbox {V}\) (a), \(-\,300\,\hbox {V}\) (b), \(-\,400\,\hbox {V}\) (c) and \(-\,500\,\hbox {V}\) (d)

5.5 Charge collection efficiency as a function of the depths

To determine the z-dependence of the charge collection efficiency, the energy depositions \(E_{\mathrm{tot}}\) are sorted into 32 equally distant depth bins. In each bin, the average energy deposition is determined and normalized to the maximal energy measured in a single bin \(E_{\mathrm{max}}\). The resulting graphs are given in Fig. 14. Hereby, we make use of the fact that the energy losses of a 40 GeV/c pion in the relatively thin medium are negligible compared to its energy, so that the particle stopping power stays constant along its path.

Overall, the expected tendency to detect less charge at greater distance to the pixel sites is confirmed. The lower the bias voltage, the higher are the maximal charge losses. While in the measurements at bias \(-\,\,300\,\,\,\hbox {V}\), \(-\,\,400\,\,\,\hbox {V}\) and \(-\,\,\,\,500\,\,\,\hbox {V}\), charge losses did not exceed \(0.1\,E_{\mathrm{max}}\), at bias \(-\,\,\,\,100\,\,\,\hbox {V}\), charge losses up to \(0.35\,E_{\mathrm{max}}\) were observed. Since charge sharing plays a significant role especially at low absolute bias voltage and signal processing includes comparison to a THL level, the presented results additionally take into account the energy lost in pixels where the induced charge stays below the threshold. Such losses are higher at greater z and lower absolute bias.

Event displays of electron-like interactions. \(E_{\mathrm{dep}}\) stands for the energy left by the event in the sensor layer. a Electron track passing through the whole sensor. The bias was set at \(-\,\,400\,\,\,\hbox {V}\); b electron track created in the sensor. The bias was set at \(-\,\,100\,\,\,\hbox {V}\); c two electron-like events emerging from the very same location within the sensor and leaving the sensitive volume. The bias was set at \(-\,\,300\,\,\,\hbox {V}\)

6 3D reconstructed particle events

The reconstruction methods discussed in Sect. 3 were applied to the set of measured data. The analyzed events were categorized by their corresponding particles:

-

Pions When the beam shutter is open, the majority of tracks relates to the interaction of 40 GeV/c pions. Pion events with outgoing \(\delta \)-rays are shown in Figs. 15 and 16. The stopping power was determined by the total energy deposit (including the \(\delta \)-ray) \(E_{\mathrm{dep}}\) divided by the density \(\rho _{\mathrm{CdTe}} = 5.85\,\nicefrac {\mathrm{g}}{\mathrm{cm}^{3}}\) [14] and the primary pion’s track length in the sensor L:

$$\begin{aligned} \frac{dE}{dX} = \frac{E_{\mathrm{dep}}}{\rho _{\mathrm{CdTe}} \times L}. \end{aligned}$$(11)In order to determine L, the iterative 3D Hough transform algorithm described in [25] was applied to the data. The algorithm returns a line parametrization in the form:

$$\begin{aligned} \mathbf {r}(\lambda ) = \mathbf {r}_{0} + \lambda \times \mathbf {u} =\begin{pmatrix} x_{0}\\ y_{0}\\ z_{0} \end{pmatrix} + \lambda \times \begin{pmatrix} dx \\ dy \\ dz \\ \end{pmatrix}, \end{aligned}$$(12)with the normalized directional vector \(\mathbf {u}\). L is thus given by evaluating the line parameterization at the entrance and exit points: \(L = |\mathbf {r}(\lambda _{\mathrm{entry}}) - \mathbf {r}(\lambda _{\mathrm{exit}})|\).

-

Muons: When the beam shutter is closed, pions are stopped so that only few muons per spill penetrate. The track shown in Fig. 17a was observed during interventions in the experimental area when the shutter was closed. We use this track to determine the precision of 3D trajectory reconstruction. Therefore, the line representation:

$$\begin{aligned} \mathbf {r}(\lambda ) = \mathbf {r}_{0} + \lambda \times \mathbf {u} =\begin{pmatrix} x_{0}\\ y_{0}\\ 0 \end{pmatrix} + \lambda \times \begin{pmatrix} dx \\ dy \\ 1 \,\upmu \mathrm m \end{pmatrix} \end{aligned}$$(13)with the four independent parameters \(x_{0}\), \(y_{0}\), dx and dy was fitted to the measured data. The distances of measured data points to the fit are shown in Fig. 17(b). Their distribution can be described by a gaussian with a \(\sigma \) of 59.4 \(\upmu \hbox {m}\). With the fit results summarized in Table 3, we find the uncertainty of the pivot point \(\mathbf {r}_{0}\) determination:

$$\begin{aligned} \varDelta r_{0} = \sqrt{\varDelta x_{0}^2+ \varDelta y_{0}^2} = 0.44\,\upmu \mathrm m, \end{aligned}$$(14)and the distance d dependent uncertainty caused by the directional vector:

$$\begin{aligned} \varDelta dr = \frac{d}{|\mathbf {u}|} \times \sqrt{\varDelta dx^2 + \varDelta dy^2} = d \times 0.00018. \end{aligned}$$(15)The precision as a function of the distance d can thus be estimated conservatively by:

$$\begin{aligned} \varDelta r(d) = \varDelta r_{0} + \varDelta u = 0.44\,\upmu \mathrm{m} + d \times 0.00018. \end{aligned}$$(16)Evaluating Eq. 16 for example at a distance of 1 m, we find a precision of \(\varDelta r(1\,\mathrm{m}) = 184\,\upmu \mathrm m\).

-

Electrons/positrons: Electron/positron tracks are characterized by curly paths through the sensor volume. Typical examples are depicted in Fig. 18. Whereas in Fig. 18a, an electron enters the sensor from the outside, the electrons/positrons in Fig. 18b and c were generated inside the sensor layer, e.g. as a result of \(\gamma \)-interactions (Compton- or photoelectric effect in the case of Fig. 18b and pair-production in the case of Fig. 18c).

-

Fragmentation reactions Rarely, particle interaction in the medium causes a break up of a nucleus in the sensor medium. A fragmentation event was found in the measurement at \(-\,\,100\,\,\,\hbox {V}\). It is illustrated in Fig. 19. Characteristic are tracks of different stopping power originating in the same point.

Since the relative drift times within a track are used for trajectory reconstruction, absolute z-determination can be done

-

if a particle (almost) fully traverses the sensor, which is the case in Figs. 15, 16, 17a and 18b. In a practical use case, such events can be selected by requiring a maximal time difference within a track close to the drift times expected from the sensor thickness;

-

if the event geometry allows to make assumptions about entry or exit point(s), which is the case in Figs. 18c and 19, where it is unlikely that secondary particles all stop exactly at the same interaction depth.

As discussed in [2], by reading out the signal at the common back side contact, even without prior assumptions, absolute depth determination could be done. Research going in this direction has already been started [26].

7 Conclusion

The presented work described the application of Timepix3 for particle tracking on a microscopic scale. Particle interactions could be reconstructed in a 2 mm thick CdTe volume in 3D while simultaneously determining the energy deposition in the sensor medium along the particle trajectory. Timepix3 was therefore used in a similar way to a TPC: the x and y coordinates were given by the detector pixelation and the z-coordinate was determined from the charge carrier drift times. The presented analysis methods corrected the energy measurement for charge carrier losses during charge carrier drift motion.

The achievable z-resolution was studied at different bias voltages. The effects of drift time model inaccuracies were separated from the uncertainties due to the time measurement. It was shown that a perfect modeling of the drift time in the sensor would provide a z-resolution down to \(60\,\upmu \hbox {m}\). Thus, with the pixel pitch of \(55\,\upmu \hbox {m}\), a device equivalent to a voxel detector with voxel size \(55 \times 55 \times 60\,\upmu \hbox {m}^{3}\) could be created.

Event displays of 3D reconstructed particle interactions with different origins were presented. By 3D line fitting, the precision of particle trajectory reconstruction was determined as a function of distance to the detector.

Data Availability Statement

This manuscript has no associated data or the data will not be deposited. [Authors’ comment: Raw or preprocessed data and analysis software used can be provided by the corresponding author upon request.]

Notes

Conseil Europeen pour la Recherche Nucleaire.

ADVACAM s.r.o., U Pergamenky 12, 170 00 Praha 7, Czech Republic, http://advacam.com/.

References

Z. Vykydal, J. Jakubek, T. Holy, S. Pospisil, in Proceedings of the 9th Conference, Villa Olmo, Como, ed. by M. Barone, E. Borchi, A. Gaddi, C. Leroy, L. Price, P.G. Rancoita, R. Ruchti (World Scientific Publishing, 2006), pp. 779–784

M. Filipenko, T. Gleixner, G. Anton, T. Michel, Eur. Phys. J. C 74(8), 3013 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-014-3013-1

D. Turecek, J. Jakubek, P. Soukup, J. Instrum. 11(12), C12065 (2016). http://stacks.iop.org/1748-0221/11/i=12/a=C12065

N. Pacifico, et al., Nuclear instruments and methods in physics research section A: accelerators, spectrometers, detectors and associated equipment 831, 12 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2016.03.057. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0168900216300808. Proceedings of the 10th International ’Hiroshima’ Symposium on the Development and Application of Semiconductor Tracking Detectors

B. Bergmann, M. Pichotka, S. Pospisil, J. Vycpalek, P. Burian, P. Broulim, J. Jakubek, Eur. Phys. J. C 77(6), 421 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-017-4993-4

T. Poikela, J. Plosila, T. Westerlund, M. Campbell, M.D. Gaspari, X. Llopart, V. Gromov, R. Kluit, M. van Beuzekom, F. Zappon, V. Zivkovic, C. Brezina, K. Desch, Y. Fu, A. Kruth. J. Instrum. 9(05), C05013 (2014). http://stacks.iop.org/1748-0221/9/i=05/a=C05013

C. Granja, S. Polansky, Z. Vykydal, S. Pospisil, A. Owens, Z. Kozacek, K. Mellab, M. Simcak. Planet. Space Sci. 125, 114 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pss.2016.03.009. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0032063316300216

S. Gohl, B. Bergmann, C. Granja, A. Owens, M. Pichotka, S. Polansky, S. Pospisil. J. Instrum. 11(11), C11023 (2016). http://stacks.iop.org/1748-0221/11/i=11/a=C11023

S. Gohl, B. Bergmann, H. Evans, P. Nieminen, A. Owens, S. Posipsil. Adv. Space Res. (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asr.2018.11.016. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0273117718308706

J. Jakubek, C. Granja, B. Hartmann, O. Jaekel, M. Martisikova, L. Opalka, S. Pospisil. J. Instrum. 6(12), C12010 (2011). http://stacks.iop.org/1748-0221/6/i=12/a=C12010

R. van Gastel, I. Sikharulidze, S. Schramm, J. Abrahams, B. Poelsema, R. Tromp, S. van der Molen. Ultramicroscopy 110(1), 33 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultramic.2009.09.002. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0304399109001983

T. Michel, T. Gleixner, J. Durst, M. Filipenko, S. Geißelsöder. Adv High Energy Phys. 2013, (2013). https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/105318

X. Llopart, R. Ballabriga, M. Campbell, L. Tlustos, W. Wong. Nuclear Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Acceler. Spectrom. Detect. Assoc. Equip. 581(1–2), 485 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2007.08.079. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0168900207017020. VCI 2007 Proceedings of the 11th International Vienna Conference on Instrumentation

A. Owens, Compound Semiconductor Radiation Detectors (CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group, Suite, 2012)

J. Fink, H. Krüger, P. Lodomez, N. Wermes. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Acceler. Spectrom. Detect. Assoc. Equip. 560(2), 435 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2006.01.072. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0168900206001598

M. Campbell, E. Heijne, T. Holy, J. Idarraga, J. Jakubek, C. Lebel, C. Leroy, X. Llopart, S. Pospisil, L. Tlustos, Z. Vykydal. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Acceler. Spectrom. Detect. Assoc. Equip. 591(1), 38 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2008.03.096. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0168900208003963. Radiation Imaging Detectors 2007

J. Bouchami, A. Gutierrez, A. Houdayer, J. Idarraga, J. Jakubek, C. Lebel, C. Leroy, J.P. Martin, M. Platkevic, S. Pospisil. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Acceler. Spectrom. Detect. Assoc. Equip.607(1), 196 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2009.03.147. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S016890020900641X. Radiation Imaging Detectors 2008

H.G. Spieler, E.E. Haller, IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 32(1), 419 (1985). https://doi.org/10.1109/TNS.1985.4336867

E. Gatti, A. Longoni, P. Rehak, M. Sampietro, Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 253, 393 (1987)

S. Ramo, in Proceedings of the I.R.E, vol. 27, 584–585. (1939) https://doi.org/10.1109/JRPROC.1939.228757

W. Shockley, J. Appl. Phys. 9(10), 635 (1938). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1710367

S. Del Sordo, L. Abbene, E. Caroli, A.M. Mancini, A. Zappettini, P. Ubertini, Sensors 9(5), 3491 (2009). https://doi.org/10.3390/s90503491. http://www.mdpi.com/1424-8220/9/5/3491

W. Riegler, G.A. Rinella, Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Acceler. Spectrom. Detect. Assoc. Equip. 767, 267 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2014.08.044. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0168900214009796

E. Frojdh, M. Campbell, M.D. Gaspari, S. Kulis, X. Llopart, T. Poikela, L. Tlustos. J. Instrum. 10(01), C01039 (2015). http://stacks.iop.org/1748-0221/10/i=01/a=C01039

C. Dalitz, T. Schramke, M. Jeltsch, Image Process. On Line 7, 184 (2017). https://doi.org/10.5201/ipol.2017.208

M. Holik, J. Broulim, V. Georgiev, Y. Mora, J. Zich, in 2017 25th Telecommunication Forum (TELFOR), pp. 1–4 (2017) https://doi.org/10.1109/TELFOR.2017.8249416

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Lukas Tlustos for the useful discussion, ADVACAM s.r.o for lending us the detector for measurements, the AFP (ATLAS Forward Proton) detector group for allowing us a parasitic measurement and the Medipix collaboration for the development of the detector. The work was supported by the European Regional Development Fund-Projects “Van de Graaff Accelerator - a Tunable Source of Monoenergetic Neutrons and Light Ions” (No. CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/16_013/0001785) and “Engineering applications of physics of microworld” (No. CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/16_019/0000766). This research has further been supported by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic under the “RICE - New Technologies and Concepts for Smart Industrial Systems”, project No. LO1607.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Funded by SCOAP3

About this article

Cite this article

Bergmann, B., Burian, P., Manek, P. et al. 3D reconstruction of particle tracks in a 2 mm thick CdTe hybrid pixel detector. Eur. Phys. J. C 79, 165 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-019-6673-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-019-6673-z