Abstract

Hadron decay chains constitute one of the main sources of information on the QCD spectrum. We discuss the differences between several partial wave analysis formalisms used in the literature to build the amplitudes. We match the helicity amplitudes to the covariant tensor basis. Hereby, we pay attention to the analytical properties of the amplitudes and separate singularities of kinematical and dynamical nature. We study the analytical properties of the spin-orbit (LS) formalism, and some of the covariant tensor approaches. In particular, we explicitly build the amplitudes for the \(B\rightarrow \psi \pi K\) and \(B\rightarrow \bar{D}\pi \pi \) decays, and show that the energy dependence of the covariant approach is model dependent. We also show that the usual recursive construction of covariant tensors explicitly violates crossing symmetry, which would lead to different resonance parameters extracted from scattering and decay processes.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The high quality data on hadron production and decays that are or will be available from BaBar, BelleII, BESIII, CMS, CLAS12, COMPASS, GlueX, LHCb, and other experiments, necessitate rigorous amplitude analysis. This is particularly true for the extraction of resonance parameters that are based on analytical partial waves. Moreover, analytical reaction amplitudes are needed in conjunction with lattice data to study the hadron spectrum from first-principles lattice QCD calculations [1,2,3,4,5].

In this paper, we focus on three-body decays, aka 1-to-3 processes. In recent years such reactions have led to ample data that resulted in the observation of new exotic phenomena, e.g. the so-called XYZ states in heavy meson decays [6,7,8], and that are also used in studies of excited mesons and baryons. The issues we address and the methodology we present are, however, of relevance to other analyses as well, for example to baryon resonance studies in photoproduction [9, 10], or meson spectroscopy from pion or photon beam fragmentation [11,12,13].

In the modern literature, there seems to be a lot of confusion regarding properties of the reaction amplitudes employed in analyses of such processes. This is often stated in the context of a potentially nonrelativistic character of certain approaches [9, 14, 15]. As we explain below, however, rather than arising from relativistic kinematics, the differences between the various formalisms have a dynamical origin. Reaction amplitudes are given by the scattering matrix elements between initial and final states that represent asymptotically free particles. Such states belong to a unitary, noncovariant representation of the Lorentz group. Since the scattering operator is a Lorentz scalar, reaction amplitudes share the transformation properties of the free particle states. A typical three particle decay process is dominated by two-body resonances, and can be well approximated by a finite number of partial waves. The latter can be given by the helicity partial waves or the Russell–Saunders, aka LS amplitudes [16]. For the LS amplitudes, one couples particle states in the canonical representation. The relation between the helicity and LS basis is a straightforward orthogonal transformation. Because of the noncovariant transformation properties of the reaction amplitude, partial waves transform in a nontrivial way as well, e.g. helicity amplitudes mix under Lorentz boosts through Wigner rotations. Nevertheless, all of the amplitudes referred to above (the helicity amplitudes, the helicity partial waves, the LS partial wave amplitudes) are relativistic, i.e. have well defined behavior under Lorentz transformations.

Since the helicity amplitudes involve asymptotically free particle states, they must be proportional to free particle wave functions, e.g. Dirac spinors or polarization tensors. These wave functions have mixed transformation properties, i.e. have both covariant (Lorentz or Dirac), and noncovariant (helicity) indices. The Lorentz and Dirac indices need to be contracted with covariant tensors built from particle four-vectors and Dirac gamma matrices to yield the noncovariant helicity amplitudes. Helicity amplitudes can therefore be expressed as linear combinations of products of covariant tensors and wave functions with coefficients that are scalar functions of the Mandelstam invariants. It can be shown that these scalar functions have only dynamical singularities as demanded by unitarity [17], and for this reason are useful when analyzing singularities of the partial waves. Furthermore, these scalar functions are invariant under crossing which makes them convenient to relate amplitudes in the decay and scattering kinematics.

There exist an approach for constructing the scalar functions from an assumed model for the partial waves, hereafter referred to as the covariant projection method (CPM) [14, 18,19,20], that starts from a LS partial wave model (or equivalently the Cartesian, aka Zemach amplitudes [21]) but writes them in a covariant fashion. The method has a drawback, which is related to the behavior under crossing (see Sect. 3.1). The alternative, which we refer to as the canonical approach [16, 22,23,24,25], is to use the well known relation between the helicity amplitudes and the helicity partial waves [16] to determine the scalar functions in terms of the partial wave models. The differences between these two approaches to relate partial waves and scalar functions result in factors which are confusingly referred in the literature as “relativistic corrections”. These are actually Lorentz invariant functions and therefore can be absorbed into the scalar functions. In both the CPM and canonical approaches, the relativistic kinematics is properly taken into account. Thus, the differences in these approaches are dynamical in nature.

In what follows, we present a detailed comparison of these two approaches, paying specific attention to the analytical properties, which are among the few constraints that can be imposed in a model independent way. Instead of presenting results for a general case, we find it more pedagogical to compare these constructions in a few concrete examples. The examples we discuss are of special interest to various ongoing analyses, and are complex enough to illustrate the general principles. The first example is the parity violating (PV) three-body decay \(B^0 \rightarrow \psi \pi ^- K^+\), with \(\psi = J/\psi , \psi (2S)\). The analyses by Belle and LHCb show nontrivial structures appearing in the \(\psi (2S) \,\pi \) [25,26,27,28], and in the \(J/\psi \,\pi \) channel [29]. These are of particular interest, because a resonance in these channels would require an exotic interpretation [6,7,8]. The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2 we discuss the canonical approach on the example of the \(B\rightarrow \psi \pi K\) decay. By relating the helicity partial waves to the scalar amplitudes via the partial wave expansion, we derive constraints and isolate the kinematical singularities. We also discuss implication of these constraints for the LS partial wave amplitudes. The details of the amplitude parameterizations are given in the Appendices and are presented in a way that can be implemented in the standard data analysis tools [30, 31]. In Sect. 3 we examine the CPM approach and compare this model with the findings from Sect. 2. We mention the crossing symmetry properties of CPM using, as an example, \(B^0 \rightarrow \bar{D}^0 \pi ^+ \pi ^-\), which was recently analyzed by LHCb within this formalism [32]. Summary and conclusions are given in Sect. 4.

2 Analyticity constraints for \(B\rightarrow \psi \pi K\)

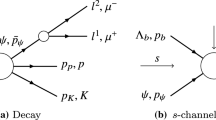

In Fig. 1 we show a diagram representing the kinematics of the decay \(B \rightarrow \psi (\rightarrow \mu ^+\mu ^-) \pi K\). The spinless particles B, \(\pi \), K are stable against the strong interaction. The \(\psi \) is narrow enough to completely factorize its decay dynamics. Thus, we construct the amplitude considering \(\psi \) to be stable. More details, including the dilepton decay of the \(\psi \), are given in Appendices A and B. We use \(p_i\), \(i=2\dots 4\) to label the momenta of B, \(\pi \), and K respectively. The momentum of the \(\psi \) will be denoted by \(\bar{p}_1\), for a reason which we will explain below. The helicity amplitude for the decay process \(B\rightarrow \psi \pi K\) is denoted by \(\mathcal {A}_\lambda (s,t)\), \(\lambda \) being the helicity of \(\psi \), i.e. \(\langle \psi \pi K, \text {out}| B, \text {in}\rangle = (2\pi )^4\delta ^4(p_2-\bar{p}_1-p_3-p_4) \mathcal {A}_\lambda \). The amplitude depends on the standard Mandelstam variables \(s = (p_3+p_4)^2\), \(t = (\bar{p}_1+p_3)^2\), and \(u = (\bar{p}_1 + p_4)^{2}\) with \(s + t + u = \sum _i m_i^2\).

The B meson decays weakly, so \(\mathcal {A}_\lambda \) is given by the sum of a PV and parity conserving (PC) amplitude. The difficulty treating the decay channel directly is that the mass of the decaying particle should be considered on the same footing as the other dynamical variables (s, t, u). This is demanded by unitarity, which implies that above a threshold, the amplitude is a singular function of the corresponding dynamical variable. It is therefore simpler to study singularities in a scattering channel and cross to the other channels by analytical continuation in the momentum of the \(\psi \), i.e. by setting \(\bar{p}_1 = -p_1\) [33]. In general, under crossing, helicity amplitudes are mixed by Wigner rotations. In our case, however, since crossing can be realized through a (unphysical) boost in the direction of motion of the \(\psi \), there is no change in helicity.

We begin with the discussion of the PV amplitudes in the s-channel. The s-channel resonances correspond to the \(K^*\)’s and dominate the reaction. As discussed in the previous section, the analysis of the experimental data indicates a possible signal of resonances in the exotic \(\psi \pi \) spectrum, which in our notation correspond to the t-channel. Once we have constructed the s-channel amplitudes, the t-channel ones can be treated similarly (cf. Appendix B).

In the center of mass of the s-channel scattering process, the \(\psi \) momentum defines the z-axis, the momenta \(p_3\) and \(p_4\) lie in the xz-plane. We call p (q) to the magnitude of the incoming (outgoing) three momentum. The scattering angle \(\theta _s\) is a polar angle of the pion (see Fig. 2). The quantities depend on the Mandelstam invariants through

with \(\lambda _{ik} = \left( s - (m_i+m_k)^2\right) \left( s - (m_i-m_k)^2\right) \). The function n(s, t) is a polynomial in s, t. To incorporate resonances in the \(\pi K\) system with a certain spin j, we expand the amplitude in partial waves,

where \(A^j_{\lambda }(s)\) are the helicity partial wave amplitudes in the s-channel. In Eq. (2) the entire t dependence enters though the d functions. The d functions have singularities in \(z_s\) which lead to kinematical singularities in t of the helicity amplitudes \(\mathcal {A}_\lambda \). The dynamical singularities in t, related to, for example, the possible resonances in the \(\psi \pi \) channel, can only be reproduced if the the sum contains the infinite number of partial waves. In practice the t- or u-channel resonances (singularities) are accounted for explicitly through t- or u-channel partial waves, and to avoid double counting each series is truncated at a finite number of terms. This defines the so-called isobar model in which

with,

where \(J_\text {max}\) is finite. However, we remark that the analysis of kinematical singularities has general validity, and might be applied to the original untruncated series.

The expressions for the (t) and (u) isobars are similar to Eq. (4). Note, that due to the superscript (s) the amplitudes \(A_{\lambda }^{(s) j}(s)\) are not identical to the helicity partial waves, \(A_{\lambda }^{j}(s)\) of Eq. (2). This is because the other two terms on the right hand side of Eq. (3) also contribute to the s-channel partial wave expansion. We refer to the former as the isobar partial waves or simply, isobars. The difference between the partial waves, which are defined in a model independent way, and isobars, which appear in the specific model as in Eq. (3), has important consequences when establishing the relation between phases of the isobar amplitudes and those of the partial waves [34,35,36,37,38,39,40]. This issue, however, is not directly related to the topic of this paper and we do not discuss it any further.

We return to the partial wave expansion, and proceed with the analysis of kinematical singularities. An extensive discussion and the full characterization of these singularities can be found in [16, 41,42,43,44,45]. We recall that \(d_{\lambda 0}^j(z_s) = \hat{d}_{\lambda 0}^j(z_s) \xi _{\lambda 0}(z_s)\), where \(\xi _{\lambda 0}(z_s) = \left( \sqrt{1-z_s^2}\right) ^{|\lambda |} =\sin ^{|\lambda |} \theta _s\) is the so-called half angle factor that contains all the kinematical singularities in t. The reduced rotational function \(\hat{d}_{\lambda 0}^j(z_s)\) is a polynomial in s and t of order \(j - |\lambda |\) divided by the factor \(\lambda _{12}^{(j-|\lambda |)/2}\lambda _{34}^{(j-|\lambda |)/2}\). The helicity partial waves \(A_\lambda ^j(s)\) have singularities in s. These have both dynamical and kinematical origin. The former arise, for example, from s-channel resonances. The kinematical singularities, just like the t-dependent kinematical singularities, arise because of external particle spin. We explicitly isolate the kinematic factors in s, and denote the kinematical singularity-free helicity partial wave amplitudes by \(\hat{A}_\lambda ^j(s)\).Footnote 1 First, the term \((p q)^{j - |\lambda |}\) is factorized out from the helicity amplitude \(A_\lambda ^j(s)\). This factor is there to cancel the threshold and pseudothreshold singularities in s that appear in \(\hat{d}^j_{\lambda 0}(z_s)\). Second, we follow [16] and introduce the additional kinematic factor \(K_{\lambda 0}\) (‘±’ is short for \(\lambda =\pm 1\)). These factors are required to account for a mismatch between the j and L dependence in the angular momentum barrier factors in presence of particles with spin. Finally, the kinematical singularity-free helicity partial wave amplitudes \(\hat{A}_\lambda ^j(s)\) are defined by

with \(K_{00}\) and \(K_{\pm 0}\) given by

Specifically, it is expected that \(A_\lambda ^j(s) \sim p^{L_1} q^{L_2}\) at threshold, where \(L_1\) and \(L_2\) are the lowest possible orbital angular momenta in the given helicity and parity combination. This explains why \(j = 0\) requires a special treatment [45], since for \(j \ge 1\) we have \(L_1 = j - 1\), but for \(j = 0\) the lowest is \(L_1 = j + 1\). In addition, the K-factors have powers of \(\sqrt{s}\) as required to ensure factorization of the vertices of Regge poles. Similarly, as explained before, \(m_1\) is dynamical and thus the kinematical singularity-free amplitudes are not expected to contain singularities in \(m_1^2\), and as will be seen below, the \(m_1\) dependence of the K-factor takes care of that. The \(\hat{A}_\lambda ^j(s)\) are left as dynamic functions, which are unknown in general and cannot be calculated from first principles. Usually they are parameterized in terms of a sum of Breit-Wigner amplitudes with Blatt–Weisskopf barrier factors.

We now seek a representation of \(\mathcal {A}_\lambda (s,t)\) in terms of the scalar functions, as discussed in Sect. 1. For the PV amplitude this is given by

Although the second term in brackets may look like an extra 1 / s pole, it cancels when multiplied by \((p_3+p_4)^\mu \). This choice simplifies the final expressions, but we remark that any other choice of independent tensor structures would lead to the same results. In the s-channel center of mass frame the \(\psi \) polarization vectors are given by \(\epsilon ^\mu (\pm ,p_1) = (0,\mp 1, -i, 0)/\sqrt{2}\) for the transverse polarizations and \(\epsilon ^\mu (0,p_1) = (|p_1|/m_1, 0, 0, E_1/m_1)\) for the longitudinal polarization. The energies \(E_i\) are calculated from the momenta and are fully determined by s. The functions B(s, t) and C(s, t) are the kinematical singularity free scalar amplitudes discussed in the Sect. 1.

We can match Eqs. (2) and (6), and express the scalar functions as a sum over kinematical singularity free helicity partial waves. The ratio \(A_\lambda (s,t)/\left( K_{\lambda 0}\,\xi _{\lambda 0}(z_s)\right) \), computed using Eq. (6), is compared to the same ratios computed using the helicity partial waves from Eq. (2). This yields

from \(\lambda = \pm \) and \(\lambda =0\), respectively, which can be combined to obtain

Neither B(s, t) nor C(s, t) can have kinematical singularities in s or t. In Eqs. (7)–(9), \(\hat{d}^j_{10}(z_s)\) is regular in t, and the s singularities at (pseudo)thresholds are canceled by the factor \((pq)^{j-1}\). The latter factor contains a high-order pole at \(s=0\). Such pole is a feature of the dynamical model, and specifically arises because at \(s=0\) the little group is not SO(3) anymore. The latter motivates the partial wave expansion, thus it is not surprising that the truncation of the partial wave series results in such singularities [16, 46].Footnote 2 This construction hence does not constrain the poles at \(s=0\).

For the same reason the sum in Eq. (9) has no kinematical singularities in s and t, however the \(1/\lambda _{12}\) factor in front of the sum generates two poles at \(s_{\pm } = (m_1\pm m_2)^2\), unless the expression in brackets vanishes at those points. This means that the \(\hat{A}^j_\lambda (s)\) with different \(\lambda \) cannot be independent functions at the (pseudo)threshold. Explicitly, in the limit \(s\rightarrow s_{\pm }\) at fixed t one has \(z_s \rightarrow \infty \) and using [43],

one finds that the expression within the brackets in Eq. (9) behaves as

This combination has to vanish to cancel the \(1/\lambda _{12}\), thus one finds (for \(j>0\))

where \(g_j(s)\), \(f_j(s)\), \(g'_j(s)\), and \(f'_j(s)\) are regular functions at \(s=s_\pm \), and \(g_j(s_\pm )=g'_j(s_\pm )\). Note that, while the functional form considered in Eq. (12) complies with the general requirements we are imposing, it actually implements more freedom than required by the former. For instance, one could take \(f_j(s)=0\) without any loss of generality. The particular choice taken in Eq. (12), however, turns out to be useful for the comparisons with other parameterizations (LS and CPM) which we will discuss in Sect. 3. Together with Eq. (12), the expressions in Eqs. (6), (8) and (9) provide the most general parameterization of the amplitude that incorporates the minimal kinematic dependence that generates the correct kinematical singularities as required by analyticity.

Upon restoration of the kinematic factors, the original helicity partial wave amplitudes read (\(j>0\))

and \(A_{0}^0(s) = \lambda _{12}^{1/2}/(2m_1)\,\hat{A}_{0}^0(s)\), where \(\hat{A}_{0}^0(s)\) is regular at (pseudo)threshold. A particular choice of the functions \(g_j(s)\), \(g_j'(s)\), \(f_j(s)\) and \(f_j'(s)\) constitutes a given hadronic model. A specific example is given in Appendix B.

2.1 Implications for the LS partial wave amplitudes

The advantage of the LS basis is that the identification of the correct threshold factors is straightforward. For a given system of two particles with spins \(j_1\), \(j_2\) and corresponding helicities \(\lambda _1\), \(\lambda _2\), the relation between a two-particle state in the helicity and LS basis is

where \(\Lambda \) is the projection of the total angular momentum j. For the \(B \rightarrow \psi \pi K\) amplitude, it implies the following relation between the LS amplitudes G and the helicity amplitudes,

The amplitudes with \(L=j\pm 1\) and \(L=j\) differ by parity. Equation (15) can be inverted to relate the helicity partial wave amplitudes with the LS amplitudes \(G_l^j(s)\),

In Eq. (16) we denoted the LS partial wave amplitudes with the threshold factors explicitly factored out by \(\hat{G}_l^j(s)\), i.e. \(G_{j\pm 1}^{j}(s) = p^{j\pm 1} \,q^j \,\hat{G}_{j \pm 1}^{j}(s)\). We now compare the general expression for the helicity partial waves with the spin-orbit LS partial waves. We find that Eq. (16) matches the general form in Eq. (12) when

The common lore is that the LS formalism is intrinsically nonrelativistic. However, the matching in Eq. (17) proves that the formalism is fully relativistic, but care should be taken when choosing a parameterization of the LS amplitude so that the expressions in Eq. (17) are free from kinematical singularities. For example, if one takes the functions \(\hat{G}^j_{j-1}(s)\) and \(\hat{G}^j_{j+1}(s)\) to be proportional to Breit–Wigner functions with constant couplings, the amplitudes \(g'_j(s)\) and \(f'_j(s)\) would end up having a pole at \(s = m_2^2 - m^2_1\), and/or a branch point at \(s=0\) unexpected for boson-boson scattering. On the other hand, as discussed in Sect. 2, the pole at \(s=0\) is part of the dynamical model. It is clear that using Breit–Wigner parameterizations, or any other model for helicity amplitudes, i.e. the left-hand sides of Eq. (17), instead of the LS amplitudes helps prevent unwanted singularities.

3 Comparison with the covariant projection method

We consider now the CPM approach of [14, 18,19,20]. As said, the method is based on the construction of explicitly covariant expressions. To describe the decay \(a \rightarrow b c\), we first consider the polarization tensor of each particle with index i and spin \(j_i\), \(\epsilon ^i_{\mu _1\dots \mu _{j_i}}(p_i)\). Using the decay momentum \(p_{bc}=(p_b-p_c)/2\) and the total momentum \(P_{bc}=p_b+p_c\), we build a tensor \(X_{\mu _1\dots \mu _{L}}(p_{bc},P_{bc})\) to represent the orbital angular momentum of the bc system. In order to find total angular momentum tensor, we first combine the polarizations of b and c into a “total spin” tensor \(S_{\mu _1\dots \mu _{S}}\!\left( \epsilon _b,\epsilon _c\right) \) (orthogonal to the momentum \(p_b+p_c\)). Then, we combine the tensor \(S_{\mu _1\dots \mu _{S}}\!\left( \epsilon _b,\epsilon _c\right) \) with the orbital tensor \(X_{\mu _1\dots \mu _{L}}\) and finally contract the result with the polarization of a, thus mimicking the LS construction. The tensors S and X have definite spin and parity, i.e. are in an irreducible representation of the rotation group in the particle rest frame. Thus they must be symmetric, traceless, and orthogonal to the total momentum in the particles system, \(p_b+p_c\). If one of the daughters is unstable, we can implement its decay in a similar way. The procedure is recursive, and relatively simple for low spins. Together with the explicit covariance, it makes the formalism very attractive.

We use the CPM to build the amplitude for \(B\rightarrow \psi \pi K\). The construction of an amplitude for an arbitrary spin of the intermediate state is cumbersome, and we limit ourselves to the special case of an intermediate \(K^*\) with \(j=1\). We start with the tensor amplitude for the scattering process \(\psi B \rightarrow K^* \rightarrow \pi K\). The orbital angular momentum of the decay \(K^* \rightarrow \pi K\) in \(P\)-wave is given by \(X_\rho (q, P)\). The tensor is constructed from a four-vector of the relative momentum \(q^\mu = (p_3^\mu -p_4^\mu )/2\) and the total momentum of the system \(P^\mu = p_3^\mu +p_4^\mu = p_1^\mu +p_2^\mu \). For the PV amplitudes, the initial process \(\psi B\rightarrow K^*\) is described by two waves. The corresponding orbital tensors are the unit rank-0 tensor for the \(S\)-wave and rank-2 tensor \(X_{\rho \mu }(p,P)\), with \(p^\rho = (p_{1}^\rho - p_{2}^\rho )/2\), for the \(D\)-wave. Hence

where P is the \(K^*\) momentum. The final \(P\)-wave orbital tensor is \(X_{\nu }(q,P) = q^\perp _\nu = q_\nu - P_\nu P\cdot q /s\). The \(D\)-wave orbital tensor \(X^{\rho \mu }(p,P)=3 p^\rho _\perp p^\mu _\perp /2-g^{\rho \mu }_\perp p_\perp ^2/2\), with \(p_\perp ^\mu = p^\mu - P^\mu \,P\cdot p/s\), and \(g^{\rho \mu }_\perp = g^{\rho \mu } - P^\rho P^\mu /s\). Explicitly,

and matching with Eq. (12) gives

The threshold conditions \(g_1(s_\pm ) = g_1'(s_\pm )\) are satisfied, and the functions \(f_1(s)\) and \(f_1'(s)\) are regular at the thresholds. Finally, we show the relation between the CPM and the LS amplitudes. The comparison with Eq. (16) leads to

Although the \(g_S(s)\) and \(g_D(s)\) of the CPM formalism, see Eq. (18), are typically interpreted as the S and D partial wave amplitudes, we see that this is the case only at (pseudo)threshold \(s=s_\pm \), where the factor \(E_1/m_1-1\) vanishes. In Sect. 3.2 we discuss a specific example to show the numerical difference between the various approaches.

3.1 Crossing symmetry; and the decay \(B\rightarrow \bar{D} \pi \pi \)

An issue with the CPM formalism is the explicit violation of crossing symmetry. The recursive procedure explained in [14, 18,19,20] produces different scalar amplitudes if applied in the scattering or in the decay kinematics. For the decay kinematics, the CPM amplitude is constructed according to a chain \(B\rightarrow \psi K^*(\rightarrow K\pi )\). The tensor \(X_\nu (q,P)\) describes the \(P\)-wave decay \(K^*\rightarrow K\pi \) as before. \(S\)- and \(D\)-waves are still possible for the decay \(B\rightarrow \psi K^*\). The same symbolic expression in Eq. (18) holds for the decay kinematics, but \(X_{\mu \nu }\) is now constructed from the relative momentum \(\hat{p} = (P - \bar{p}_1)/2\) between \(K^*\) and \(\psi \) in the B rest frame (we restored the \(\bar{p}_1\) for the momentum of the \(\psi \) in the decay kinematics), and orthogonalized with respect to the B momentum \(p_2\),

where \(X^{\rho \mu }\) depends on \(\hat{p}_\perp ^\mu = \hat{p}^\mu - p_{2}^{\mu }\, p_2\cdot \hat{p}/m_2^2\), and \(\hat{g}_{\perp }^{\rho \mu } = g^{\rho \mu }-p_2^\rho p_2^\mu /m_2^2\). As mentioned before, crossing symmetry requires the helicity amplitude \(A_\lambda (s,t)\) to be the same up to a phase for the decay and the scattering process. The expressions for the helicity amplitudes read

where \(\gamma (s)=(s-m_1^2+m_2^2)/(2 m_2 \sqrt{s})\) is the boost factor of \(K^*\) in the B rest frame discussed in [14, 19]. The matching to the general form in Eq. (12) is analogous. Although Eqs. (19) and (23) agree at threshold, the dynamical models differ in general, and the additional factors appearing in Eq. (23) are part of the model.

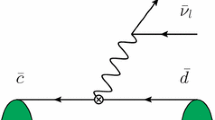

The issue with the crossing symmetry is particularly interesting, and we want to illustrate it further on a simpler example. We consider the decay \(B\rightarrow \bar{D}\pi \pi \). This reaction has been analyzed by LHCb using the CPM formalism [32]. Since none of the external particles have spin, the reaction is described by a single scalar amplitude. Because of crossing symmetry, the amplitude is the same scalar function of the Mandelstam variables in both scattering and decay kinematics. We consider the s-channel scattering kinematics \(B D \rightarrow \pi ^+\pi ^-\). We use the indices 1, 2, 3 and 4 for the D, B, \(\pi ^+\) and \(\pi ^-\) momenta. Therefore, \(P = p_1 + p_2\) is the center of mass momentum, \(s = P^2\) is the invariant mass of the \(\pi \pi \) system, and p and q are the breakup momenta for the initial and final states. For simplicity, we restrict this discussion to the case of a spin-1 isobar, \(B D \rightarrow \rho \rightarrow \pi ^+\pi ^-\). The CPM amplitude is given by

In the center of mass frame of the s-channel, \(X^\mu (p,P) = \left( 0,0,0,p\right) \) and \(X^\nu {(q,P)} = \left( 0,q\sin \theta _s,0,q \cos \theta _s\right) \) are purely spacelike vectors proportional to the breakup momenta. Therefore, the amplitude in Eq. (24) matches the expectations. For the decay process, the orbital tensor \(X^\mu (p,P)\) is replaced by \(X^\mu (\hat{p},p_2)\) to be orthogonalized to the four-momentum \(p_2\). As a result, a factor \(\gamma (s) = (s-m_1^2+m_2^2)/(2m_2\sqrt{s})\) appears, and the breakup momentum from the \(B \rightarrow \bar{D} \rho \) orbital tensor is evaluated in the rest frame of B. The amplitudes for the decay process crossed to the scattering kinematics are

The two amplitudes differ by a factor \(\gamma (s)\sqrt{s}/m_2=(s-m_1^2+m_2^2)/(2m_2^2)\). While this factor is analytic in s and does not spoil the counting of kinematical singularities discussed in the previous section, its appearance breaks crossing symmetry and this shows the drawback of the CPM formalism.

The issues arise from the construction of an amplitude as subsequent one-to-two decays. At first sight this appears as a natural choice. However, a well defined amplitude should have only asymptotic states on the external legs. This would exclude any decay into a resonance. One needs to take a step back to the definition of a resonance, i.e. a pole in the scattering amplitude. Therefore, the consistent procedure would be to write the amplitude in the scattering kinematics and then use crossing symmetry to analytically continue the amplitude into the decay region.

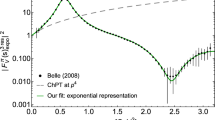

3.2 \(K\pi \)-mass distribution in different approaches

To explore the differences between the various approaches, we consider the example of two intermediate vectors in the \(\pi K\) channel: the \(K^*(892)\), with mass and width \(M_{K^*}=892\) MeV, \(\Gamma _{K^*} = 50\) MeV, and the \(K^*(1410)\), with \(M_{K^*}=1414\) MeV, \(\Gamma _{K^*} = 232\) MeV. The differential width is given by the expression,

where \(\rho (s) = \lambda _{12}^{1/2}\lambda _{34}^{1/2}/s\), and \(N_j\) is a normalization constant. In Fig. 3 we show the results for five different scenarios. We consider the CPM formalisms discussed in Eqs. (19) and (23) (for the scattering and decay kinematics, respectively), setting \(g_S(s)=0\) and \(g_D(s) = T_{K^*}(s)\), with

For the LS formalism, we choose the couplings in Eq. (16) to be \(\hat{G}_0^1(s)=0\), \(\hat{G}_2^1(s)=T_{K^*}(s)\). The LS amplitude in the decay kinematics differs from the one in the scattering kinematics only because of the breakup momentum of \(B \rightarrow \psi K^*\), calculated in the B rest frame or in the \(K^*\) rest frame, respectively. Finally, we draw a line for our proposal given by Eq. (B3), the only nonzero term in the sum is \(F_2^1(s) = T_{K^*}(s)\).

The partial wave amplitudes for two-to-two scattering processes are proportional to \(p^{L_1}q^{L_2}\), where p (q) are the initial (final) state break up momentum and the particles in \(L_1\)(\(L_2\))-waves. This behavior comes from the expansion of the amplitude at threshold, and generates an unphysical growth at higher energies. This behavior is customarily modified by model-dependent form factors.Footnote 3 The most popular approach is based on a nonrelativistic model introduced by Blatt and Weisskopf [48, 49]. For the plot on the right in Fig. 3 we multiply the amplitudes by the Blatt–Weisskopf barrier factors

for the initial \(P\)- and final \(D\)-waves, respectively. The couplings are set as \(g_S(s) = \hat{G}_0^1(s) = F_0^1(s) = 0\) and \(g_D(s) = \hat{G}_2^1(s) = F_2^1(s) = T_{K^*}(s)B_1(q)B_2(p)\) for the corresponding formalisms in Eqs. (18), (19) and (B3). The constant R is chosen to be \(5\,\)GeV\(^{-1}\), which corresponds \(1\,\)fm, i.e. the scale of the strong interaction.

We see in Fig. 3 that the \(K\pi \) invariant mass squared distribution is distorted differently in all models. It is straightforward to track down where the differences come from. In the JPAC amplitude of Eqs. (B3) and (B4), the threshold factor in the \(F_2^1(s)\) function in Eq. (B3) is set to \(\lambda _{12}\), in contrast to the CPM and LS formalisms where the factor \(p^2 = \lambda _{12}/(4s)\) is used. This makes the differential width distribution different by the factor \(1/s^2\). Another difference originates from the factor \(E_1/m_1\) for the \(A_0(s)\) amplitude which was required by analyticity. We showed that it is not present in the LS approach, as one can see in Eq. (16). In the physical domain this factor behaves as \(1/\sqrt{s}\) at the amplitude level, resulting in 1 / s difference in the the differential width.

4 Summary and conclusions

We considered different approaches for constructing amplitudes for scattering and decay processes. Although the problem might be viewed as standard exercise, there seems to be confusion among amplitude analysis practitioners, as to which formalism best represents S-matrix constraints [18, 19]. Specifically, we have compared the canonical helicity formalism [16, 22,23,24,25] and the covariant projection method [14, 18,19,20]. We used analyticity as a guiding principle to examine these approaches. Using as example the decay \(B\rightarrow \psi \pi K\), and the helicity formalism, we separated the kinematical factors from the dynamical functions. We then matched the helicity amplitudes with the most general covariant expression. In this process we identified kinematical constraints on the helicity amplitudes. We have shown that the naïve parameterization of the LS couplings fails to satisfy all the constraints required by analyticity. We found that, in contrast to LS parameterization, an extra factor \((s+m_1^2-m_2^2)/(2m_1\sqrt{s})\) naturally appears in the tensor formalism when written for the scattering kinematics. More interestingly, the customary recipes in the CPM approach explicitly violate crossing symmetry. In particular, we showed that the tensor approach discussed in [14, 18,19,20], when applied to the decay kinematics directly, introduces a peculiar energy dependence which has no clear physical motivation.

To address the issue of the relativistic corrections, we recall the relation between the helicity and the LS amplitudes. This relation is valid for any energy. The concept of the spin-orbit decomposition is fully relativistic. However, analyticity prevents the LS couplings to be parameterized as simple constants. We remark that our observations and conclusions are strictly valid only when asymptotic states are considered. We performed extensive studies for the four-legs process which describes two-to-two scattering, or the one-to-three decay, when the mother particle has an (infinitely) narrow width. The extension to other reactions requires dedicated studies.

Regarding the question raised in the title, we conclude that the helicity formalism is the right guide. Specifically, kinematical singularities have been classified for helicity partial waves. However, crossing to the decay channel is more natural for covariant amplitudes, while the LS amplitudes have the correct threshold behavior built in. Since a model for an amplitude is always required, examining the behavior of all of these amplitudes as we did here can maximize the consistency of the model with S-matrix principles.

References

D.J. Wilson, R.A. Briceno, J.J. Dudek, R.G. Edwards, C.E. Thomas, Phys. Rev. D 92, 094502 (2015). arXiv:1507.02599 [hep-ph]

R.A. Briceño, J.J. Dudek, R.G. Edwards, D.J. Wilson, Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 022002 (2017). arXiv:1607.05900 [hep-ph]

R.A. Briceño, J.J. Dudek, R.G. Edwards, D.J. Wilson, “Isoscalar \(\pi \pi , K\overline{K}, \eta \eta \) scattering and the \(\sigma , f_0, f_2\) mesons from QCD” (2017). arXiv:1708.06667 [hep-lat]

R.A.Briceño, J.J. Dudek, R.D.Young, “Scattering processes and resonances from lattice QCD”, (2017), arXiv:1706.06223 [hep-lat]

B. Hu, R. Molina, M. Döring, A. Alexandru, Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 122001 (2016). arXiv:1605.04823 [hep-lat]

R.F. Lebed, R.E. Mitchell, E.S. Swanson, Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 93, 143 (2017). arXiv:1610.04528 [hep-ph]

A. Esposito, A. Pilloni, A.D. Polosa, Phys. Rept. 668, 1 (2016). arXiv:1611.07920 [hep-ph]

S.L. Olsen, T. Skwarnicki, D. Zieminska, “Non-Standard Heavy Mesons and Baryons, an Experimental Review”, (2017). arXiv:1708.04012 [hep-ph]

A.V. Anisovich, R. Beck, E. Klempt, V.A. Nikonov, A.V. Sarantsev, U. Thoma, Eur. Phys. J. A 48, 15 (2012). arXiv:1112.4937 [hep-ph]

R.L. Workman, M.W. Paris, W.J. Briscoe, I.I. Strakovsky, Phys. Rev. C 86, 015202 (2012). arXiv:1202.0845 [hep-ph]

P. Abbon et al. (COMPASS), Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 779,68 (2015), arXiv:1410.1797 [physics.ins-det]

M. R. Shepherd (GlueX), in Proceedings, 10th Conference on the Intersections of Particle and Nuclear Physics (CIPANP 2009): San Diego, USA, May 26-31, 2009, Vol. 1182 (2009) pp.816–819

D.I. Glazier, Proceedings, International Meeting of Excited QCD 2015: Tatranska Lomnica, Slovakia, March 8–14, 2015. Acta Phys. Polon. Supp. 8, 503 (2015)

S.U. Chung, Phys. Rev D 48, 1225 (1993). [Erratum: Phys. Rev.D56,4419(1997)]

C. Adolph et al., COMPASS. Phys. Rev. D 95, 032004 (2017). arXiv:1509.00992 [hep-ex]

P.D.B. Collins, http://www-spires.fnal.gov/spires/find/books/www?cl=QC793.3.R4C695 An Introduction to Regge Theory and High-Energy Physics,Cambridge Monographs on Mathematical Physics(Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, UK, 2009)

G. Cohen-Tannoudji, A. Morel, H. Navelet, Ann. Phys. 46, 239 (1968a)

S.-U. Chung, J. Friedrich, Phys. Rev. D 78, 074027 (2008). arXiv:0711.3143 [hep-ph]

V. Filippini, A. Fontana, A. Rotondi, Phys. Rev. D 51, 2247 (1995)

A.V. Anisovich, A.V. Sarantsev, Eur. Phys. J. A 30, 427 (2006). arXiv:hep-ph/0605135 [hep-ph]

C. Zemach, Phys. Rev. 140, B97 (1965)

M. Jacob, G.C. Wick, Ann. Phys. 7, 404 (1959) [Reprint: Ann. Phys. 281, 774 (2000)]

S.U. Chung, Spin Formalisms, CERN-71-08. http://cds.cern.ch/record/186421

R. Kutsckhe, An angular distribution cookbook. http://home.fnal.gov/~kutschke/Angdist/angdist.ps

R. Mizuk et al., Belle. Phys. Rev. D 80, 031104 (2009). arXiv:0905.2869 [hep-ex]

K. Chilikin et al., Belle. Phys. Rev. D 88, 074026 (2013). arXiv:1306.4894 [hep-ex]

R. Aaij et al., LHCb. Phys. Lett. B 747, 484 (2015a). arXiv:1503.07112 [hep-ex]

R. Aaij et al., LHCb. Phys. Rev. D 92, 112009 (2015b). arXiv:1510.01951 [hep-ex]

K. Chilikin et al., Belle. Phys. Rev. D 90, 112009 (2014). arXiv:1408.6457 [hep-ex]

H. Matevosyan, R. Mitchell, M. Shepherd, AMPTOOLS package. https://github.com/mashephe/AmpTools/wiki

S. Neubert, ROOTPWA package. https://github.com/ROOTPWA-Maintainers/ROOTPWA/wiki

R. Aaij et al., LHCb. Phys. Rev. D 92, 032002 (2015c). arXiv:1505.01710 [hep-ex]

T.L. Trueman, G.C. Wick, Ann. Phys. 26, 322 (1964)

N.N. Khuri, S.B. Treiman, Phys. Rev. 119, 1115 (1960)

F. Niecknig, B. Kubis, S.P. Schneider, Eur. Phys. J. C 72, 2014 (2012). arXiv:1203.2501 [hep-ph]

F. Niecknig, B. Kubis, JHEP 10, 142 (2015). arXiv:1509.03188 [hep-ph]

I.V. Danilkin, C. Fernández-Ramírez, P. Guo, V. Mathieu, D. Schott, M. Shi, A.P. Szczepaniak, Phys. Rev. D 91, 094029 (2015). arXiv:1409.7708 [hep-ph]

P. Guo, I.V. Danilkin, D. Schott, C. Fernández-Ramírez, V. Mathieu, A.P. Szczepaniak, Phys. Rev. D 92, 054016 (2015). arXiv:1505.01715 [hep-ph]

A. Pilloni, C. Fernández-Ramírez, A. Jackura, V. Mathieu, M. Mikhasenko, J. Nys, A.P. Szczepaniak, JPAC. Phys. Lett. B 772, 200 (2017). arXiv:1612.06490 [hep-ph]

M. Albaladejo, B. Moussallam, Eur. Phys. J. C 77, 508 (2017). arXiv:1702.04931 [hep-ph]

Y. Hara, Phys. Rev. 136, B507 (1964)

L.-L.C. Wang, Phys. Rev. 142, 1187 (1966)

J.D. Jacksonand, G.E. Hite, Phys. Rev. 169, 1248 (1968)

G. Cohen-Tannoudji, A. Kotański, P. Saling, Phys. Lett. 27B, 42 (1968b)

A. Martin, T. Spearman, Elementary particle theory (North-Holland Pub Co, Amsterdam, 1970)

M. Toller, Nuovo Cim. 37, 631 (1965)

D.Z. Freedman, J.-M. Wang, Phys. Rev. 153, 1596 (1967)

J.M. Blatt, V.F. Weisskopf, Theoretical nuclear physics (Springer, New York, 1952)

F. Von Hippel, C. Quigg, Phys. Rev. D 5, 624 (1972)

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the inspiring atmosphere at the PWA9/ATHOS4 workshop where the idea for this work was born. AP thanks Greig Cowan and Jonas Rademacker for useful discussions about the application of the different formalisms in LHCb. MM and AP would like to thank Suh-Urk Chung and Andrey Sarantsev for several useful discussion about the CPM approach, Dmitry Ryabchikov for sharing his experience with partial wave analysis using the Zemach and LS formalisms, and Anton Ivashin for several useful discussions. This work was supported by BMBF, the U.S. Department of Energy under grants No. DE-AC05-06OR23177 and No. DE-FG02-87ER40365, PAPIIT-DGAPA (UNAM, Mexico) grant No. IA101717, CONACYT (Mexico) grant No. 251817, Research Foundation – Flanders (FWO), U.S. National Science Foundation under award numbers PHY-1507572, PHY-1415459 and PHY-1205019, and Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (Spain) through grant No. FPA2016-77313-P.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix A: Parity-conserving amplitudes in the s channel

We consider the most general scattering amplitude for \(\psi B\rightarrow \pi K\) with parity conservation enforced. The only tensor structure allowed is

where the Levi–Civita tensor is defined by \(\epsilon _{0123} = 1\) and D(s, t) is the singularity free scalar amplitude.

As follows from the derivation in [16], the kinematical factor is \(K_{\pm 0} = \sqrt{s}\, p q=\lambda _{12}^{1/2}\lambda _{34}^{1/2}/(4\sqrt{s})\), i.e. the minimal L in the final and initial states matches j. Removing also the half-angle factor \(\xi _{10}(z_s) =\sin \theta _s\), we get

where the partial wave helicity amplitudes can be written as

Finally, we can match the scalar amplitude D(s, t) with the partial waves helicity amplitudes,

Appendix B: The minimal singularity-free parameterization of the helicity amplitudes

We consider a model for the reaction \(B\rightarrow \psi \pi K\), using the general parameterization of the helicity amplitudes obtained in Sect. 2 and Appendix A. We use the isobar model of Eq. (3), and neglect any u-channel (\(\psi K\)) resonant contribution. We already provided the covariant form of the s-channel amplitude \(A_\lambda ^{(s)}(s,t)\) in Eq. (6), where the scalar functions B and C are related to the kinematical singularity free helicity partial waves \(\hat{A}_\lambda ^{(s),j}\). The general form is in Eq. (12). A particular choice of the functions \(g_j^{(s)}\), \(g_j^{(s)\prime }\), \(f_j^{(s)}\) and \(f_j^{(s)\prime }\) determines our model. To match the LS parameterization at threshold, we set

where \(F_{l}^{(s),j}\) are independent dynamical functions,

The amplitudes in the t-channel are analogous to the s-channel ones upon replacement of momenta and masses, \(2\leftrightarrow 3\). The corresponding dynamical functions are \(F_{l}^{(t),j}\).

Combining the s-channel PV amplitude in Eq. (6), the s-channel PC amplitude in Eq. (A1), and their t-channel counterparts, the full amplitude reads

with \(x=s,t\), and

The decay \(\psi \rightarrow \mu ^+ (q_{2}) \mu ^-(q_{1})\) can be attached by contracting the tensor amplitude \(A_\mu \) from Eq. (B5) with the tensor given by the fermion vector current.

The square of the leptonic tensor summed over the unobserved polarizations of the leptons yields

The amplitude is linear in the dynamical functions \(F_l^{(x),j}\), i.e.

where the index j is the spin in the x-channel. The sum over j goes from 0 to \(\infty \) in general, while in the considered isobar model one includes only the terms with relevant resonances. The orbital angular momentum l runs over \(j-1,j,j+1\). In the special case \(j = 0\), the possible values of l are 0 and 1 only. The functions \({F^{(x),j}_{l}}\) contain the dynamical input. They include the resonance amplitude (e.g. parameterized by the Breit-Wigner formula) and left hand singularities (e.g. Blatt-Weisskopf barrier factors). The \((Z_{l}^{xj})_\mu \) are kinematic functions responsible for the right angular dependence. The square of the matrix element is a bilinear form in the dynamical functions

The expression for the kinematic function \((Z_{l}^{xj})_\mu \) is given in Eq. (B14). The first two terms in Eq. (B14) are used for the PV decay, the last term for the PC one

The functions \(C_\mu ^x\), \(B_\mu ^x\), and \(D_\mu ^x\) describe the tensor structures in front of \(C^{(x)}\), \(B^{(x)}\), and \(D^{(x)}\) in Eq. (B5). The functions \(\zeta _{l}^{xj}\), \(\beta _{l}^{xj}\) and \(\delta _{l}^{xj}\) take over the kinematic dependence of the functions \(C^{(x)}\), \(B^{(x)}\) and \(D^{(x)}\), i.e. they are factors in front of \({F^{(x),j}_{l}}\)

with

The special case \(j = 0\) has \(\zeta _{l}^{x0} = \beta _{0}^{x0} = \beta _{-1}^{x0} = \delta _{l}^{xj} = 0\) and \(\beta _{1}^{x0} = \sqrt{3}/(4\pi )\).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Funded by SCOAP3

About this article

Cite this article

Joint Physics Analysis Center., Mikhasenko, M., Pilloni, A. et al. What is the right formalism to search for resonances?. Eur. Phys. J. C 78, 229 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-018-5670-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-018-5670-y