Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Although nearly all elderly Americans are insured through Medicare, there is substantial variation in their use of services, which may influence detection of serious illnesses. We examined outpatient care in the 2 years before breast cancer diagnosis to identify women at high risk for limited care and assess the relationship of the physicians seen and number of visits with stage at diagnosis.

DESIGN: Retrospective cohort study using cancer registry and Medicare claims data.

PATIENTS: Population-based sample of 11,291 women aged ≥67 diagnosed with breast cancer during 1995 to 1996.

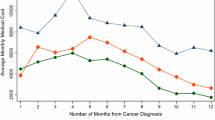

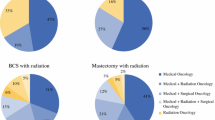

MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS: Ten percent of women had no visits or saw only physicians other than primary care physicians or medical specialists in the 2 years before diagnosis. Such women were more often unmarried, living in urban areas or areas with low median incomes (all P≥.01). Overall, 11.2% were diagnosed with advanced (stage III/IV) cancer. The adjusted rate was highest among women with no visits (36.2%) or with visits to physicians other than primary care physicians or medical specialists (15.3%) compared to women with visits to either a primary care physician (8.6%) or medical specialist (9.4%) or both (7.8%) (P<.001). The rate of advanced cancer also decreased with increasing number of visits (P<.001).

CONCLUSIONS: Even within this insured population, many elderly women had limited or no outpatient care in the 2 years before breast cancer diagnosis, and these women had a markedly increased risk of advanced-stage diagnosis. These women, many of whom were unmarried and living in poor and urban areas, may benefit from targeted outreach or coverage for preventive care visits.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Institute of Medicine. Care Without Coverage: Too Little Too Late. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2002.

Kaiser Family Foundation. The Medicare Program: Medicare at a Glance. Washington, DC; 2004. Available at: www.kff.org/medicare/1066-07.cfm. Accessed November 10, 2004.

Asch SM, Sloss EM, Hogan C, Brook RH, Kravitz RL. Measuring underuse of necessary care among elderly Medicare beneficiaries using inpatient and outpatient claims. JAMA. 2000;284:2325–33.

Flocke SA, Stange KC, Zyzanski SJ. The association of attributes of primary care with the delivery of clinical preventive services. Med Care. 1998;36:AS21-AS30.

Ettner SL. The relationship between continuity of care and the health behaviors of patients: does having a usual physician make a difference? Med Care. 1999;37:547–55.

Safran DG, Taira DA, Rogers WH, Kosinski M, Ware JE, Tarlov AR. Linking primary care performance to outcomes of care. J Fam Pract. 1998;47:213–20.

Mechanic D. Changing medical organization and the erosion of trust. Milbank Q. 1996;74:171–89.

Weyrauch KF. Does continuity of care increase HMO patients’ satisfaction with physician performance? J Am Board Fam Pract. 1996;9:31–6.

Ries LAG, Eisner MP, Kosary CL, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1973–1999. Bethesda, MD, 2002:Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1973_1999/. Accessed June 14, 2002.

NCI Breast Cancer Screening Consortium. Screening mammography: a missed clinical opportunity? Results of the NCI Breast Cancer Screening Consortium and National Health Interview Survey Studies. JAMA. 1990;264:54–8.

Blustein J. Medicare coverage, supplemental insurance, and the use of mammography by older women. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1138–43.

Burns RB, McCarthy EP, Freund KM, et al. Variability in mammography use among older women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:922–6.

McCarthy EP, Burns RB, Coughlin SS, et al. Mammography use helps to explain differences in breast cancer stage at diagnosis between older black and white women. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:729–36.

McCarthy EP, Burns RB, Freund KM, et al. Mammography use, breast cancer stage at diagnosis, and survival among older women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1226–33.

Aiken LH, Lewis CE, Craig J, Mendenhall RC, Blendon RJ, Rogers DE. The contribution of specialists to the delivery of primary care. N Engl J Med. 1979;300:1363–70.

Scherger JE. Primary care physicians and specialists as personal physicians: can there be harmony? J Fam Pract. 1998;47:103–4.

Rosenblatt RA, Hart LG, Baldwin LM, Chan L, Schneeweiss R. The generalist role of specialty physicians: is there a hidden system of primary care? JAMA. 1998;279:1364–70.

Potosky AL, Riley GF, Lubitz JD, Mentnech RM, Kessler LG. Potential for cancer related health services research using a linked Medicaretumor registry database. Med Care. 1993;31:732–48.

Ries LA, Wingo PA, Miller DS, et al. The annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1973–1997, with a special section on colorectal cancer. Cancer. 2000;88:2398–424.

American Joint Committee on Cancer. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 5th ed. New York, NY: Springer Verlag; 1997.

Ellis RP, Pope GC, Iezzoni LI, et al. Diagnosis-based risk adjustment for Medicare capitation payments. Health Care Financ Rev. 1996;17:101–28.

Ash AS, Posner MA, Speckman J, Franco S, Yacht AC, Bramwell L. Using claims data to examine mortality trends following hospitalization for heart attack in Medicare. Health Serv Res. 2003;38:1253–62.

Burns RB, McCarthy EP, Freund KM, et al. Black women receive less mammography even with similar use of primary care. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:173–82.

Randolph WM, Mahnken JD, Goodwin JS, Freeman JL. Using Medicare data to estimate the prevalence of breast cancer screening in older women: comparison of different methods to identify screening mammograms. Health Serv Res. 2002;37:1643–57.

Baron RM, Kenney DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51:1173–82.

Arora NK, Johnson P, Gustafson DH, McTavish F, Hawkins RP, Pingree S. Barriers to information access, perceived health competence, and psychosocial health outcomes: test of a mediation model in a breast cancer sample. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;47:37–46.

Little RJ. Direct standardization: a tool for teaching linear models for unbalanced data. Am Stat. 1982;36:38–43.

Leape LL, Hilborne LH, Bell R, Kamberg C, Brook RH. Underuse of cardiac procedures: do women, ethnic minorities, and the uninsured fail to receive needed revascularization? Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:183–92.

Jemal A, Tiwari R, Murray T, et al. Cancer statistics, 2004. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54:8–29.

Jencks SF, Cuerdon T, Burwen DR, et al. Quality of medical care delivered to Medicare beneficiaries: a profile at state and national levels. JAMA. 2000;284:1670–6.

Institute of Medicine. Leadership by Example—Coordinating Government Roles in Improving Healthcare Quality. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2002.

Sisk JE. How are health care organizations using clinical guidelines? Health Aff (Millwood). 1998;17:91–109.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. The Facts About Upcoming New Benefits in Medicare: Medicare Modernization Act of 2003. Publication number CMS-11054. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services; 2004.

Starfield B. Is primary care essential? Lancet. 1994;344:1129–33.

Starfield B. Primary Care: Balancing Health Needs, Services, and Technology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1998.

Institute of Medicine. Primary Care: America’s Health in a New Era. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1996.

Lichtenberg FR. The effects of Medicare on health care utilization and outcomes. In: Garber AM, ed. Frontiers in Health Policy Research Conference. 5 vol. Washington, DC; 2001. Available at: http://www.nber.org/~confer/2001/fronts01/lichtenberg.pdf. Accessed June 14, 2002.

Wells BL, Horm JW. Stage at diagnosis in breast cancer: race and socioeconomic factors. Am J Public Health. 1992;82:1383–5.

Ayanian JZ, Kohler BA, Abe T, Epstein AM. The relation between health insurance coverage and clinical outcomes among women with breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:326–31.

Hunter CP, Redmond CK, Chen VW, et al. Breast cancer: factors associated with stage at diagnosis in black and white women. Black/White Cancer Survival Study Group. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:1129–37.

Baldwin LM, Adamache W, Klabunde C, Kenward K, Dalhman C, Warren JL. Linking physician characteristics and Medicare claims data: issues in data availability, quality, and measurement. Med Care. 2002;40:IV-82–IV-95.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Dr. Ayanian is a consultant to Research Triangle Institute and DxCG, Incorporated on the development of DCG risk adjustment models. None of the other authors have potential conflicts to report.

This work was funded by a Clinical Scientist Development Award to Dr. Keating from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. This study used the Linked SEER-Medicare database. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the sole responsibility of the authors. The authors acknowledge the efforts of the Applied Research Program, National Cancer Institute; the Office of Information Services and the Office of Strategic Planning, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; Information Management Services, Incorporated; and the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program tumor registries in the creation of the SEER-Medicare database.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Keating, N.L., Landrum, M.B., Ayanian, J.Z. et al. The association of ambulatory care with breast cancer stage at diagnosis among medicare beneficiaries. J GEN INTERN MED 20, 38–44 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.40079.x

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.40079.x