Abstract

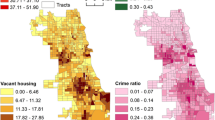

Physical inactivity contributes to a growing proportion of premature mortality and morbidity in the United States, and the last decade has been the focus of calls for action. Analysis of 340 residents of New Jersey found that 15%–20% reported multiple problems with using their immediate neighborhoods for physical activity. These respondents were disproportionately African Americans living in neighborhoods that they regard as only of fair or poor quality. Neighborhood walkability is a second-wave environmental justice issue meriting carefully designed research and ameliorative actions in concert with other neighborhood-level redevelopment activities.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Physical Activity and Health: Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 1996.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence of physical activity, including life-style activities among adults—United States, 2000–2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52:764–769.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Compliance with physical activity recommendations by walking for exercise—Michigan, 1996 and 1998. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2000;49:560–565.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Increasing physical activity, a report on recommendations of the task force on community preventive services. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2001;50:560–565.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. State-specific prevalence of selected chronic disease-related characteristics—behavioral risk factor surveillance system, 2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52:560–565.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence of no leisure time physical activity—35 states and the District of Columbia, 1988–2002. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53:82–86.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Physical activity trends—United States, 1990–1998. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2001;50:166–169.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence of physical activity, including life-style activities among adults—United States, 2000–2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52:764–769.

Powell KE, Martin LM, Chowdhury PP. Places to walk: convenience and regular physical activity. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1519–1521.

Humpel N, Owen N, Leslie E. Environmental factors associated with adults’ participation in physical activity: a review. Am J Prev Med. 2002;22:188–199.

Giles-Corti B, Donovan RJ. The relative influence of individual, social, and physical environmental determinants of physical activity. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54:1793–1812.

Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup D, Gererding JL. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2004;291:1238–1245.

U.S. Centers for Disease Control. Report of the Secretary’s Task Force on Black and Minority Health. Vol 10. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1985.

Byrd WM, Clayton LA. An American Health Dilemma, Race, Medicine and Health Care in the United States: 1900–2000. Vol 2. New York, NY: Routledge; 2002.

Cervero R, Duncan M. Walking, bicycling, and urban landscape: evidence from the San Francisco Bay Area. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1478–1483.

Staunton CE, Hubsmith D, Kallins W. Promoting safe walking and biking to school: the Marin County success story. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1431–1434.

Wang G, Macerca C, Scudder-Soucie B, et al. Cost analysis of the built environment: the case of bike and pedestrian trails in Lincoln, Neb. Am J Public Health. 2004; 94:549–553.

Tester JM, Rutherford G, Wald Z, Rutherford MW. A matched case-control study evaluating the effectiveness of speed bumps in reducing child pedestrian injuries. AJPH. 2004; 94:646–650.

Evans L. A new traffic safety vision for the United States. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1384–1386.

Librett JJ, Yore MM, and Schmid T. Local ordinances that promote physical activity: a survey of municipal policies. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1399–1403.

McAvoy PV, Driscoll MB, Gramling BJ. Integrating the environment, the economy, and community health: a community health center’s initiative to link health benefits to smart growth. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:525–527.

Fullilove MT. Promoting social cohesion to improve health. J Am Med Womens Assoc. 1998;53:72–76.

Leyden KM. Social capital and the built environment: the importance of walkable neighborhoods. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1546–1551.

Fishhoff B, Slovic P, Lichtenstein S, Read S, Combs B. How safe is safe enough? A psychometirc study of attitudes towards technological risks and benefits. Policy Sci. 1978;9:127–152.

Siegrist M. A causal model explaining the perception and acceptance of gene technology. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1999;22:2093–2106.

Siegrist M. The influence of trust and perceptions of risk and benefit on the acceptance of Gene Technology. Risk Anal. 2000;20:195–203.

Goszczynska M, Tyszka T, Slovic P. Risk perception in Poland: a comparison with three other countries. J Behav Decis Making. 1991;4:179–193.

Greenberg M, Schneider D. Environmentally Devastated Neighborhoods, Perceptions, Policies and Realities. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 1996.

Clinton WJ. Federal Actions to Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-income Populations. Washington, DC; 1994 Executive Order, No. 12898. Available at: http://inel.gov/program/exec/eo-12898.html.

Coburn J. Confronting the challenges in reconnecting urban planning and public health. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:541–546.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Greenberg, M.R., Renne, J. Where does walkability matter the most? An environmental justice interpretation of New Jersey data. J Urban Health 82, 90–100 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1093/jurban/jti011

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/jurban/jti011