Abstract

The strongest tradition of classroom-environment research has focused on empirically testing the relationship between the classroom environment and student outcomes. This paper reports a study conducted within this general framework. Specifically, this research investigated the relationship between the classroom environment and self-handicapping by students in Canadian high school mathematics classes. Results showed that the classroom environment accounted for appreciable proportions of variance in self-handicapping, beyond that attributable to academic efficacy. Enhanced affective dimensions of the classroom environment were associated with reduced levels of self-handicapping.

Résumé

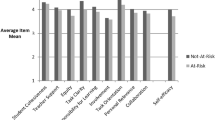

Une recherche visant à analyser les liens qui existent entre l’environnement scolaire et l’autohandicap a été menée dans des écoles secondaires de l’Ontario, au Canada. Le terme d’ ≪ environnement scolaire ≫ renvoie ici à la nature psychologique de la salle de classe. Quant à l’ ≪ autohandicap ≫, il s’agit d’une forme de comportement actif d’évitement visant à manipuler la perception des performances de façon à ce que l’élève acquière un prestige accru aux yeux d’autrui. Un échantillon de 951 étudiants provenant de quatre écoles ont répondu à un questionnaire dont le but était d’évaluer d’une part la perception des répondants au sujet de 10 variables liées à la classe comme environnement (plus précisément : la cohésion entre les étudiants, le soutien de la part des enseignants, l’engagement personnel, l’investigation, l’orientation des tâches, l’esprit de coopération, l’équité, la pertinence personnelle, le contrôle partagé et la négociation de la part des élèves), et d’autre part l’autohandicap et l’efficacité scolaire. Des analyses de corrélation simples et multiples entre ces aspects de la classe et l’autohandicap ont été menées, en prenant l’étudiant comme unité d’analyse. Les analyses ont été effectuées avec et sans contrôle de l’efficacité scolaire. Les résultats montrent que la classe comme environnement est responsable d’une partie appréciable des différences dans le degré d’autohandicap, outre celles qui sont attribuables à l’efficacité scolaire. En effet, de meilleurs aspects affectifs dans l’environnement scolaire sont associés à des niveaux d’autohandicap moins élevés.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Adams, J. (2000, April). Development of an instrument to evaluate school-level environments in the special sector: The Special School-Level Environment Questionnaire. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, New Orleans.

Cooley, W.W., & Lohnes, P.R. (1976). Evaluation research in education. New York: Irvington.

Covington, M.V. (1992). Making the grade: A self-worth perspective on motivation and school reform. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Dorman, J.P. 1999. The evolution, validation and use of a personal form of the Catholic School Classroom Environment Questionnaire. Catholic Education, 3, 141–157.

Dorman, J.P. (in press). Classroom environment research: Progress and possibilities. Queensland Journal of Educational Research.

Fraser, B. J. (1986). Classroom environment. London: Croom Helm.

Fraser, B. J. 1994. Research on classroom and school climate. In D. Gabel (Ed.), Handbook of research on science teaching and learning (pp. 493–541). New York: Macmillan.

Fraser, B.J. (1998a). Science learning environments: Assessments, effects and determinants. In B.J. Fraser & K.G. Tobin (Eds.), International handbook of science education (pp. 527–564). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer.

Fraser, B.J. (1998b). Classroom environment instruments: Development, validity, and applications. Learning Environments Research, 1, 7–33.

Goh, S.C., & Fraser, B.J. 1998. Teacher interpersonal behaviour, classroom environment and student outcomes in primary mathematics in Singapore. Learning Environments Research, 1, 199–229.

Jagacinski, C.M., & Nicholls, J.G. 1990. Reducing effort to protect perceived ability: ‘They’d do it, but I wouldn’t.’ Journal of Educational Psychology, 82, 15–21.

Kolditz, T.A., & Arkin, R.M. 1982. An impression management interpretation of self-handicapping strategy. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 43, 492–502.

Kim, H.B., Fisher, D.L., & Fraser, B.J. 1999. Assessment and investigation of constructivist learning environments in Korea. Research in Science and Technological Education, 17, 39–249.

Majeed, A., Fraser, B.J., & Aldridge, J.M. 2002. Learning environment and its association with student satisfaction among mathematics students in Brunei Darussalam. Learning Environments Research, 5, 203–226.

Midgley, C., Arunkumar, R., & Urdan, T. 1996. ‘If I don’t do well tomorrow, there’s a reason’: Predictors of adolescents’ use of academic self-handicapping strategies. Journal of Educational Psychology, 88, 423–434.

Midgley, C., Maehr, M., Hicks, L., Roeser, R., Urdan, T., Andaman, E.M., et al. (1997). Manual for the Patterns of Adaptive Learning Survey. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan.

Midgley, C., & Urdan, T. 1995. Predictors of middle school students’ use of self-handicapping strategies. Journal of Early Adolescence, 15, 389–411.

Moos, R.H. 1974. Systems for the assessment and classification of human environments: An overview. In R.H. Moos & P.M. Insel (Eds.), Issues in social ecology: Human milieus (pp. 5–28). Palo Alto, CA: National Press.

Moss, C.H., & Fraser, B.J. (2001, April). Using environment assessments in improving teaching and learning in high school biology classrooms. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Seattle.

Pyszczynski, T., & Greenberg, J. 1983. Determinants of reduction in intended effort as a strategy for coping with anticipated failure. Journal of Research in Personality, 17, 412–422.

Raaflaub, C.A., & Fraser, B.J. (2002, April). Investigating the learning environment in Canadian mathematics and science classrooms in which laptop computers are used. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, New Orleans.

Riggs, J.M. 1992. Self-handicapping and achievement. In A.K. Boggiano & T.S. Pittman (Eds.), Achievement and motivation: A social-developmental perspective (pp. 244–267). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Roeser, R.W., Midgley, C., & Urdan, T. 1996. Perceptions of the school psychological environment and early adolescents’ self-appraisals and academic engagement: The mediating role of goals and belonging. Journal of Educational Psychology, 88, 408–422.

Stevens, J. (1992). Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Taylor, P.C., Fraser, B.J., & Fisher, D.L. 1997. Monitoring constructivist classroom learning environments. International Journal of Educational Research, 27, 293–302.

Tice, D.M. 1991. Esteem protection or enhancement? Self-handicapping motives and attributions differ by trait self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60, 711–725.

Urdan, T., Midgley, C., & Anderman, E.M. 1998. The role of classroom goal structure in students’ use of self-handicapping strategies. American Educational Research Journal, 35, 101–122.

Waldrip, B.G., & Fisher, D.L. (2001). City and country students’ perceptions of teacher-student interpersonal behaviour and classroom learning environments. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, New Orleans.

Wubbels, T., & Levy, J. (Eds.). (1993). Do you know what you look like ? Interpersonal relationships in education. London: Falmer.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ferguson, J.M., Dorman, J.P. The Learning Environment, Self-Handicapping, and Canadian High School Mathematics Students. Can J Sci Math Techn 3, 323–331 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1080/14926150309556571

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/14926150309556571