Abstract

What type of information helps interest advocates get their way? While it is widely acknowledged in the academic literature that information provision is a key aspect of lobbying, few scholars have directly tested the effect of information on lobbying success. Policymakers need information both on technical aspects and public preferences to anticipate the effectiveness of a policy proposal and electoral consequences. However, scholars have found that interest groups predominantly provide the former rather than the latter, which suggests that technical information is seen as more efficient. The paper argues that lobbying success is not solely a function of the provision of any information but of the specific type of information and its composition. It furthermore argues that the relevance of different information types for lobbying success depends on issue characteristics such as public opinion, salience or complexity. Relying on new original data of advocacy activity on 50 specific policy issues in five West European countries, the paper highlights that the provision of expert information increases the likelihood of lobbying success, while the effect of information about public preferences is, if anything, negative. The study ultimately contributes to our understanding of informational lobbying, interest representation and interest group influence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Policy outcomes are often the result of multiple actors promoting competing interests (Austen-Smith and Wright 1992; Dahl 1961; Truman 1951). Who wins and who loses in such a game has attracted lots of academic and public attention. Ever since Schattschneider’s (1960) claim of bias in the ‘heavenly chorus’ interest groups are seen as a potential risk that may thwart public policies away from what the public wants (Gray et al. 2004). Pluralist accounts of interest representation, on the other hand, portray interest groups as important intermediaries between the public and the policymaking level (Rasmussen et al. 2014; Truman 1951). Interest groups face a constant organisational tension between catering to their constituents and meeting demands from policymakers, possibly at the expense of what their members and supporters want (Berkhout et al. 2017b). The latter situation may reflect a perspective on participatory democracy that is less political and receptive to public pressures, but rather technocratic (De Bruycker 2016) and could explain why interest groups primarily engage in expertise-based information provision rather than transmitting information on what the public wants (Baumgartner et al. 2009; De Bruycker 2016; Nownes and Newmark 2016).

The academic literature considers information as a key aspect of lobbying (cf. Austen-Smith 1993; Hall and Deardorff 2006; Wright 1996), yet has rarely tested the direct effect of information transmission on lobbying success empirically. Moreover, the information transmission capacity of a group has often been seen as an implicit benchmark for its ability to exert influence without examining to what extent such a group actually engages in informational lobbying. Following Wright, ‘interest groups achieve influence through the acquisition and strategic transmission of information that legislators need to make good public policy and to get reelected’ (Wright 1996, p. 2). This suggests that both policy expertise and information about public opinion are important when lobbying policymakers. Yet, research so far has mostly tested the effect of either information in general (Klüver 2011b; Tallberg et al. 2018) or technical information only (cf. Burstein and Hirsh 2007; Dür et al. 2015), not considering that interest groups provide different types of information (De Bruycker 2016). An important question remains, therefore, to what extent information provision affects lobbying success of interest groups.Footnote 1 This paper considers both expert information and information about public preferences. Expert information is defined as information about technical details, the effectiveness of a policy, its legal aspects as well as its economic impact (De Bruycker 2016). Information on public preferences refers to information on public preferences, electoral consequences or moral concerns (ibid., 601) and is not restricted to general public opinion but also includes information of a specific constituency such as stakeholders, members or a somewhat broader constituency.

Drawing on research exchange theory, the paper argues that while both types of information are expected to increase the chance of lobbying success, also the composition of information matters. Hence, emphasising expert information may increase the chance of success as the demand for and the strategic advantage of a group having such information is higher. It will, moreover, be argued that the relevance of providing either type of information for lobbying success increases as public pressure and the demand for information increases. Using measures of perceived influence and preference attainment, the theoretical argument is tested using a novel dataset collected within the larger GovLis projectFootnote 2. Drawing on a media content analysis, interviews, desk research and a survey, the dataset pools information on interest group activity of 380 actors on 50 specific policy issues in five West European countries (Denmark, Sweden, Germany, the Netherlands and the UK). While existing research focused on the US or EU context, this paper provides an account of informational lobbying in a set of Western European countries applying a cross-sectional cross-national research design.

The results suggest that only the provision of expert information increases the chance of lobbying success, while the effect of information about public preferences is, if any, negative after controlling for media attention and expert information. This is intriguing given that policymakers need both types of information and that interest groups are assumed to influence policymaking by meeting these demands (Nownes 2006; Wright 1996). A possible explanation is that weaker groups use information about public preferences as an attempt to compensate for their lack of expertise (Kriesi et al. 2007). Likewise, policymakers’ demand for such information may be lower as they have other channels to get informed about public preferences. While this study supports existing research showing that lobbying success is a function of information provision (Austen-Smith 1993; Nownes 2006; Wright 1996), it highlights the importance of distinguishing between different types of information.

Informational lobbying

Information is commonly seen as a key aspect for gaining access to policymakers and influence over policy decisions (cf. Nownes and Newmark 2016; Wright 1996). Moreover, some factors are often assumed to explain lobbying success because of the informational value they carry. For example, Bouwen (2004) argues that large and resourceful groups enjoy more access to EU institution because of the amount and type of information they are able to provide. Others assume that business groups are especially influential because of the informational advantage they have compared to other groups (Dür 2008a; Eising and Spohr 2017; Yackee and Yackee 2006). However, relatively little research has tested the direct effect of information on lobbying success. While formal theoretical accounts of informational lobbying illustrated how information can influence decision-making (Austen-Smith 1993; Austen-Smith and Wright 1992; Hall and Deardorff 2006; Lohmann 1998), some notable exceptions examine informational lobbying empirically and give valuable insights this paper aims to expand on.

For example, Dür et al. (2015) test the effect of technical information on lobbying success in the EU context and conclude that technical information decreases the positional distance between the EU commission and the advocate. Similarly, Burstein and Hirsh (2007) test the effect of information on bill enactment and observe an effect for information about the effectiveness provided by supporters on whether a policy proposal was enacted. Klüver (2011b) finds that the information that is supplied by a camp increases lobbying success. Lastly, Tallberg et al. (2018) study lobby influence in International Organisations (IO) and find information to positively affect perceived influence in some IOs. While these studies provide evidence that information is effective, they consider either one type of information only or information in general. Knowledge about the effect of information about public preferences remains scarce as well as conditions under which information is more effective. This paper considers that interest groups possess different kinds of information and gauges the effects of such types on lobbying success. It also examines whether the effect of information on lobbying success depends on issue characteristics.

Resource exchange and dependency

The relationship between interest groups and policymakers has often been portrayed as an exchange relationship as both have to rely on each other for some resources (for a review see Berkhout 2013). One of the resources policymakers have to rely on interest groups for is information (Bouwen 2002).

Following De Bruycker’s (2016) two modes of information supply, the paper distinguishes between expert information, referring to information on technical details, the effectiveness of a policy, its legal aspects and the economic impact (ibid., 599) and information on public preferences, considering information on public and constituents’ preferences, electoral consequences or moral concerns (De Bruycker 2016, p. 601). So how can such information help an actor to achieve its goals? Policymakers strive to develop good public policy and to get reelected (Wright 1996, p. 82). To do this, policymakers need information about the effectiveness of a proposal or whether it will be supported by the public and relevant stakeholders (De Bruycker 2016; Wright 1996). Policymakers often lack this information which interest groups can provide. This resource dependency creates an information asymmetry and information becomes a source of influence (Ainsworth 1993; Gilligan and Krehbiel 1989), which bears the risk of groups presenting information to their favour (Tallberg et al. 2018). Consequently, policymakers decide on an outcome that reflects a result, which would have been (slightly) different without the exchange with the interest group, which implies some degree of influence (ibid.).

As mentioned, policymakers need expert information in order to design policies that will be effective and feasible (Wright 1996, p. 82). Interest advocates possess such information because of their daily work, their members’ hands-on-experience or because they or their constituents are directly affected by the policy issue (Michalowitz 2004; Wright 1996). Such information is privately held by the advocates and not necessarily accessible for policymakers who therefore have to rely on the advocates for the information. For example, the national farmers’ association has information about the consequences of a ban of glyphosate for their members. They may even have studies and empirical evidence because they interact with their members and know how such a policy would affect them. This is a strategic advantage over others that lack such information on technical details, facts and the economic impact of a new regulation.

Policymakers furthermore need information about what the public wants to reduce uncertainties regarding the support for a new policy (Wright 1996). Scholars have often referred to this as a strategy of information politics, usually employed by financially weaker actors to compensate the lack of expertise (Beyers 2004; Kriesi et al. 2007). Given that it can be seen as an alternative route to success, it seems important to consider it in the equation. Democratic governments are expected to decide on policies that reflect public preferences (Dahl 1961) and policymakers rely on people’s vote during the next election (Mayhew 1974). For this reason they need information on how people would react to a new policy proposal. Interest groups learn through interactions with members, supporters and clients about their constituents’ preferences and therefore possess such information (Michalowitz 2004; Wright 1996). Given the policymakers’ need and interest groups’ ability to provide either type of information, the provision of expert information and information about public preferences is expected to increase the likelihood of lobbying success.

H1a

The more interest groups engage in the provision of expert information, the higher the likelihood of lobbying success. (Volume Hypothesis I)

H1b

The more interest groups engage in the provision of information on public preferences, the higher the likelihood of lobbying success. (Volume Hypothesis II)

Yet, although interest groups provide both types of information (De Bruycker 2016), the emphasis may vary. Hence, the composition of information that is provided plays a role as well. By virtue of the organisational tension (Berkhout et al. 2017b) some advocates may consider the provision of expert information as more relevant, while others prefer to predominantly transmit information on public preferences to represent their constituents’ interests.

Looking at the information portfolios of interest groups, previous studies found that groups provide more expert information than political information (Baumgartner et al. 2009; Burstein 2014; Nownes and Newmark 2016). Interest groups consider this type of information as possibily more efficient for increasing their likelihood of success. Moreover, the strategic advantage of expert information may be higher which allows for negotiating from a better position. Expert information typically refers to private information that only particular groups can provide, whereas information on public preferences may be more accessible to policymakers so that they do not have to rely on interest groups for the information (Dür 2008a). Moreover, policymakers may learn about constituency preferences through other channels at lower costs. Hence, the strategic advantage to have such information as an interest group is considerably lower. Another hypothesis therefore expects:

H2

The higher the relative emphasis on expert information, the higher the likelihood of lobbying success. (Composition Hypothesis)

However, because of the resource interdependency ‘organizations can become subject to pressures from those organizations that control the resources they need’ (Bouwen 2002, p. 368). De Bruycker argues that information on public preferences allows interest groups to exert a considerable amount of pressure which could aid advocacy success under certain circumstances. Thus, under which conditions are policymakers especially vulnerable to such pressures?

Public support and scrutiny are factors that are likely to increase the chance of success of strategies that exert pressure on policymakers (De Bruycker 2016, p. 600; Kriesi et al. 2007). For example, if public support for an actors’ position increases, so should the amount of pressure the actor can exert on policymakers. Public support is a valuable resource for interest groups to have. Public opinion plays an important role for decision-making as policymakers rely on the public’s votes for the next election (Mayhew 1974). Interest groups may want different things than the public in which case policymakers have to weigh the costs of going one way or the other. However, the likelihood of lobbying success should be considerably higher when the advocates have a high share of the public on their side (Rasmussen et al. 2018). It allows interest groups to demonstrate public support and compliance and will make it difficult for policymakers to go against public opinion. Hence, the provision of information on public preferences may be more effective when the actor credibly enjoys large public support as it increases the pressure.

Moreover, public salience of an issue may affect whether an actor increases the chances of success when providing information on public preferences. Research has found that political information is used more when public salience is higher (Mahoney 2008). Hence, if an issue is under higher public scrutiny, policymakers cannot easily follow particular interests but have to critically evaluate the positions of all actors. The pressure that actors exert if public scrutiny is higher can be ignored less when the public is able to critically monitor how policymakers act upon a policy decision.

Lastly, scholars have argued that policymakers need information particularly on complex issues (Klüver 2011a) which require predominantly technical and specialised expert information (Mahoney 2008). The need for information on such aspects should therefore increase with the complexity of an issue (Klüver 2011a) and so should the chance of lobbying success for the actor providing such information. Regulatory issues, as an example, are very technical and require more expertise on specific details than redistributive or distributive issues. Hence, actors that have expert information are more likely to be successful where the demand for such information is greater. In sum, some issue characteristics are expected to determine the effectiveness of both types of information on lobbying success.

H3a

The effect of information about public preferences on lobbying success increases with the share of public support the actor providing the information enjoys. (Pressure Hypothesis I)

H3b

The effect of information about public preferences on lobbying success increases with the public salience of a policy issue. (Pressure Hypothesis II)

H3c

The effect of expert information on lobbying success is higher on regulatory issues than on other issues. (Demand Hypothesis)

Research design

The hypotheses will be tested using data collected within the larger GovLis project (Rasmussen et al. 2018). The dataset includes information on public opinion and interest group activity on 50 specific policy issues in five West European countries (Germany, Denmark, Sweden, the UK and the Netherlands). The selection of cases considers variation in the degree to which interest groups are involved in policymaking; the UK being a country in which the interest group system is characterised as pluralist, while the Netherlands, Germany, Sweden and Denmark show different degrees of corporatism (Jahn 2016). Although some interest organisations may mobilise to push general policy in a more right or left wing direction, most lobbying activities are targeted at specific policy proposals (cf. Berkhout et al. 2017a), which is why the effect of information on lobbying success will be tested on specific policy issues. Each issue constitutes a concrete policy proposal to change the status quo, and the issues in the sample were selected as a stratified random sample from issues that occurred in nationally representative public opinion polls. The issues vary, moreover, with regard to salience, public support and policy type as these aspects are likely to have an impact on lobbying success. Issues in the sample concern for example the question whether to raise the retirement age or to cutting coal subsidies (see Appendix A for a full list of the policy issues in Supplemental Online Material).

In addition to information at the level of policy issues, the dataset considers variables at the actor level because the final unit of analysis is an actor on an issue. Actors are defined based on their observable, policy-related activities which follows a behavioural definition of interest groups (Baumgartner et al. 2009). Different steps were taken to identify the actors that mobilised on an issue. First, student assistants coded interest group statements on the specific policy issue in two major newspapersFootnote 3 in each country for a period of 4 years (Gilens 2012) or until the policy changed. Second, interviews with civil servants that have worked on the issue during our observation period (82% response rate) helped to complement the list of advocates that have mobilised on the issues. Lastly, desk research of formal tools and interactions such as public hearings or consultations was conducted in order to identify more relevant actors. From December 2016 until April 2017, an online survey was distributed amongst 1410 advocates identified as active on the specific issues. 380 answered the questions regarding the variables relevant for the analysis in this paper (see Appendix B1 for response rates in Supplemental Online Material), which results in a response rate of 27%.

Dependent variable

There are different ways of measuring lobbying success. While many studies use the preference attainment approach (Dür 2008b; Mahoney 2008; Rasmussen et al. 2018), this paper measures ‘perceived influence’ (Binderkrantz and Rasmussen 2015; Tallberg et al. 2018). While similar, these two approaches capture different meanings of influence (Pedersen 2013). The preference attainment approach is a rather ‘hard’ way of measuring lobbying success, predominantly capturing the first face of power, i.e. directly controlling the policy outcome. This measure does not consider that actors may have achieved smaller successes or side-deals. While this objective way of measuring success ensures a higher external validity (Dür 2008b), it may underestimate the effect of a subtle mechanism like information provision. The perceived influence measure, on the other hand, allows to gauge the impact of such an unobtrusive mechanism and to capture both formal and informal ways of influence (Binderkrantz and Rasmussen 2015). Given that one piece of information is not necessarily expected to change a policy, but result in smaller, more subtle changes, the effect of information provision on lobbying success is thus assessed using the perceived influence approach (Tallberg et al. 2018). Perceived Influence was measured by a question in the survey asking about the perceived impact an actor had on a policy issue, 1 meaning no impact at all, while 11 notes extremely high impact. There are some disadvantages regarding the measure of perceived influence. First, groups may have incentives to over- or underestimate their influence to demonstrate their supporters how powerful they are or to downplay their influence to avoid counter-mobilisation (Binderkrantz and Rasmussen 2015; Dür 2008b; Tallberg et al. 2018). Yet, Pedersen did not find that any type of group is more likely to be dishonest (2013), which is supported by Tallberg et al. (2018). Moreover, over- or underestimation should be less of a problem in an anonymous survey where neither members nor other groups to which the group may want to signal its relevance have access to the information (Binderkrantz and Rasmussen 2015). Second, groups may have unreliable knowledge as to how influential they are (ibid.). Yet, given that the paper looks primarily at the difference between the two types of information, there is no reason to suspect that the lack of knowledge plays out more for one dimension than for the other (cf. ibid. for a similar argument). While both measures have advantages and disadvantage, the paper takes the perceived influence approach, allowing to gauge also smaller lobbying success that may result from information provision. Nevertheless, the paper provides an analysis using the preference attainment approach as an alternative measure in the robustness section.

Independent variables

Hypothesis 1 tests the effect of providing different types of information on lobbying success. Information provision was measured by asking survey respondents how often certain arguments have been used (Appendix B2 provides an overview of the survey questions in Supplemental Online Material). Expert information consists of arguments referring to (a) facts and scientific evidence, (b) feasibility and effectiveness of the proposed policy, (c) economic impact for the country and (d) compatibility with existing legislation (De Bruycker 2016, p. 601). The answer categories range from 1 to 5, and the values for the different arguments were added and divided by four. Information on Public Preferences is based on arguments referring to public support on the issues (ibid.) as well as fairness and moral principles (Nownes and Newmark 2016). The second proxy ensures that not only information about general public opinion is included, but also how a policy will affect organisations and/or certain segments of society (Burstein 2014; Nownes and Newmark 2016). Again, the items were added and divided by two so that the final variable ranges from 1 to 5. Hypothesis 2 tests the effect of an actor placing a higher emphasis on expert information.Footnote 4Relative Expert Information is calculated by subtracting the amount of information on public preferences from expert information, which is then divided by their sum.Footnote 5 Values larger than zero indicate that the actor emphasised expert information, while values smaller than zero indicate a higher emphasis on information on public preferences. Hypothesis 3a tests the moderating effect of public support for information about public preferences. The variable Public Support for an Actor measures the share of the public an actor had on its side on an issue and is based on public opinion data and the actor’s position.Footnote 6 Hypothesis 3b explores whether the effect of information about public preferences increases when public salience increases. Saliency measures the log of the average number of articles containing a statement that have been published on an issue per day in the two coded newspapers during the observation period. Hypothesis 3c assesses the effect of expert information on regulatory issues. The variable Policy Type distinguishes between redistributive, distributive and regulatory issues (Lowi 1964), whereby the final binary variable reports a 1 for regulatory and a 0 for redistributive and distributive issues.

Control variables

Influencing policy outcomes is a complex endeavour, and success depends on multiple factors. The analysis therefore controls for a number of aspects. First, the analysis considers the alternative explanation that lobbying success is a function of other resources than information and hence includes Economic Resources as well as Perceived Media Attention (Tallberg et al. 2018). One survey question asks about the extent to which an actor agreed to have spent a large amount of economic resources on lobbying activities for the policy issue. A second question probes the extent to which the actor agreed to have a high level of media attention for their activities to scrutinise the effect of outside lobbying strategies. Respondents could answer on a five-point agreement scale with five indicating strong agreement.

The analysis furthermore considers different types of advocates, because business actors are often assumed to more likely attain their preferences (Bunea 2013; Yackee and Yackee 2006). The variable Interest Group Type (see Appendix C for an overview of the different actor types in Supplemental Online Material)Footnote 7 distinguishes between (1) citizen groups, including public interest groups and hobby & identity groups, (2) professional groups, covering trade unions and occupational groups, (3) business groups, including firms and business associations and (4) experts and others, encompassing individual experts, think tanks and institutional association.

The variable Camp Support considers that lobbying is a collective enterprise (Klüver 2011b) and controls whether a more one-sided mobilisation is likely to increase lobbying success (Mahoney 2008). It is operationalised as the share of advocates on the same side of an actor. The variable Pro Change indicates a 1 for actors favouring policy change and a 0 for those that want to keep the status quo which is included as actors aiming to challenge the status quo need to invest more to convince policymakers to risk unforeseeable consequences and are hence less likely to achieve their goal (Baumgartner et al. 2009). Lastly, Organisational Salience controls how important an actor considered an issue as this may affect the lobbying strategy and intensity and hence success. This variable is measured on a five-point scale, asking how important an actor considered an issue compared to other issues. Appendix D presents an overview of all variables including a correlation matrix in Supplemental Online Material.

Analysis

The level of observation are advocates who are nested in policy issues. Given that the models include variables both at the actor and the issue level, all models are run as multilevel models with random intercepts for policy issues to account for the heterogeneity of different policy issues and country fixed effects. The models presented in the analysis are OLS regression models.Footnote 8 All models have been built stepwise (Appendix F in Supplemental Online Material), whereas Table 1 presents only the full models including all controls.

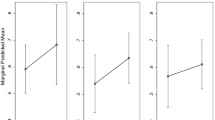

Model 1 tests Hypotheses 1a and 1b which argued that higher amounts of either type of information increase the likelihood of lobbying success. In line with Hypothesis 1a, there is a positive and significant effect for expert information (p < 0.001). Hence, in line with previous work in the US or EU context that argues that information is a valuable exchange good (Bouwen 2002), the results confirm that expert information increases the likelihood of lobbying success (Burstein and Hirsh 2007; Dür et al. 2015). However, Model 1 also shows that Hypothesis 1b cannot be confirmed. In fact, the effect of information on public preferences is negative (p < 0.01). Figure 1 presents the predicted margins and compares the effect of expert information and information on public preferences on lobbying success. While the red, dashed line shows a positive increase on perceived influence from low levels of expert information to high levels of expert information, the black, solid graph shows a reversed pattern for information on public preferences.

However, stepwise model building shows that the coefficient for information on public preferences only becomes negative in the full model when controlling for media attention or expert information (see Appendix F in Supplemental Online Material). Outside lobbying has often been seen as a ‘weapon of the weak’ (Berkhout 2013), and the negative effect of information on public preferences may rather be a result of weaker actors than the information itself. However, this also means that while some argue that information politics is used by actors with less resources (Beyers 2004; Kriesi et al. 2007), providing such information cannot be seen as an alternative route to lobbying success. Furthermore, the coefficient of information on public preferences also becomes negative when controlling for expert information. Interest groups often provide both types of information, and the possession of one type is likely to affect the provision of another type.Footnote 9 Yet when controlling for expert information it becomes clear, that eventually it is expert information that matters. Hence, one should thus consider both types of information, irrespective of whether one aims at explaining information provision (De Bruycker 2016; Mahoney 2008) or lobbying success as a function of information provision (Chalmers 2011; Klüver 2011b; Tallberg et al. 2018). Another potential reason for the negative effect for information about public preferences might lie in the issue itself as some issues cannot be easily addressed with technical expertise. For example, some issues are quite controversial as they imply a moral or ideological stance. Public exposure resulting from the controversy of the issue may make it difficult for policymakers to change sides. Interest groups trying to lobby policymakers by providing information about public preferences may find it hard to get their preferred outcome. Appendix G (Supplemental Online Material) looks more into this, including a model controlling for the controversy of an issue, which, however, does not alter the results.

Model 2 tests Hypothesis 2, which argued that the composition of information has an effect on lobbying success. The effect for this relative measure is positive and significant (p < 0.001), which suggests that actors who emphasise expert information perceive their lobbying efforts as more successful. This contributes to research arguing that information provision increases lobbying success (Bouwen 2002; Chalmers 2011; Klüver 2011b; Nownes 2006; Tallberg et al. 2018; Wright 1996) by showing that it is not about any type of information but primarily about expert information. However, the effect only becomes significant when controlling for actor level variables, the interpretation should therefore be cautious. Models 3–5 test Hypotheses 3a–c, scrutinising whether the effect of either type of information is stronger under certain circumstances. Yet, none of the interaction effects shows significant results. So while some research argues that information provision and lobbying success is context-dependent (De Bruycker 2016; Mahoney 2008), the results here do not indicate that the two modes of information supply are more effective under certain circumstances. This also means that, in order to be successful, advocates have to provide a certain amount of expert information, irrespective of how much public pressure or demand there is.

With regard to the control variables, Models 1, 2 and 5 show positive effects for public support for an actor on lobby success (p < 0.10), which confirms recent results (Rasmussen et al. 2018). Moreover, four of the five models show a positive effect of having a camp’s support for lobbying success (p < 0.10) (Mahoney 2008). There is little to no effect of economic resources, which is also in line with previous studies (Baumgartner et al. 2009; Mahoney 2008). Business groups as well as experts perceive their lobbying activities as less successful than citizen groups (p < 0.10 or lower). Perceived media attention has a strong positive effect on lobbying success in all models (p < 0.001), which indicates that those that have gained more media attention consider their activities as more successful. However, a potential reason for this effect could be the perceived influence measure itself. For example, actors might see placing an item on the public agenda as successful lobbying. Yet, the theoretical argument is about how information provision affects advocacy success when lobbying policymakers and the survey question asks about success on political decisions. The variable perceived media attention, therefore, is included to control for any kind of media success. Nevertheless, Appendix I (Supplemental Online Material) discusses this more in detail and provides further analysis. For example, Table I in Supplemental Online Material presents models excluding media attention, showing that the effect for expert information stays the same, while the significance for information about public preferences drops to p = 0.052.

Furthermore, the effect for organisational salience is significant in one of the five models, which does not indicate strong evidence that the importance actors devote to an issue affects their perceived lobbying success. Four models show furthermore positive and significant effects for regulatory issues (p < 0.05), which means that on such issues the chance of lobbying success increases. Even though the interaction term was not significant, it could suggest that the demand for interest groups is highest on such issues which increase the chance of success. Lastly, interest groups in the Netherlands perceive themselves as more successful than in Germany (p < 0.01). A potential reason could be that the Netherlands has become more corporatist over the years (Jahn 2016, p. 60) which could explain why Dutch advocates feel more included in policymaking. However, this certainly needs further research with a larger sample of countries.

Robustness and limitations

As discussed in the research design section, the perceived influence measure has some disadvantages as it is a measure based on perception. As a robustness check, the analyses therefore have been conducted with the alternative preference attainment approach (Dür 2008b). Preference attainment measures whether a policy outcome is congruent with an actor’s position on an issue (see Appendix J in Supplemental Online Material for how preference attainment was measured). Using this alternative measure of lobbying success reveals similar results (see Appendix J in Supplemental Online Material): The effect of expert information is positive (p < 0.1), while the effect of information about public preferences is negative (p < 0.05). Moreover, the composition of information has a positive and significant effect (p < 0.05). Figure 2 shows the predicted probabilities for success across the observed range of the combined measure. The predicted probabilities range from 40% for actors predominantly providing information on public preferences to 73% for actors predominantly focusing on expert information.

These results, however, should be interpreted with caution. All models have been built stepwise, yet the main effects only become significant in the full model. This underlines the caveat mentioned earlier that the test of an effect of information types on preference attainment is a hard test for a subtle mechanism. However, it also highlights that lobbying success is determined by many factors and not one single factor alone. The effects become significant after controlling for economic resources and camp support. This could indicate that the effect of information on lobbying success depends on how good the information is and that the actual effect of information is only significant after taking out variation of factors determining the quality of the information. It is unclear what makes information ‘good’ information, yet we know that in order to be efficient information has to be costly (Wright 1996). Moreover, information provided by an actor who enjoys broad support can signal information in a much more credible manner and policymakers are especially receptive for credible information (Beyers 2004; De Bruycker 2016).

Some other limitations of the study concern the venue and target of information provision as the study did not consider that interest groups use different channels to provide their information. The amount and the effect of information on public preferences may be different when considering the outside arena only. However, the study intended to look at information transmission to policymakers to gauge effects on decision-making on policies. Yet again, information provision may differ depending on whether the target of information is a bureaucrat or a parliamentarian, which the analysis cannot distinguish. Studies that can do so may find more fine-grained effects for different targets of information. Another caveat may refer to non-response bias of the survey respondents. While the overall response rate is within the margin of what is considered to be typical for interest group surveys (Marchetti 2015), there are some differences across countries. Yet, the paper does not aim at theorising about country differences but rather at generalising towards North West European policy advocates, which should be kept in mind when interpreting the findings. Summarising, the results do not provide crystal clear evidence and indicate some of the challenges of analysing the subtle effects of information transmission on policymaking. Yet, given that a lot of research works with the assumption that information matters, the empirical assessment in a cross-sectional cross-national context yields new insights and allows the tentative conclusion: The provision of expert information enhances the chance of lobbying success, while the effect of information on public preferences is, if any, negative.

Conclusion

The paper started from the argument that lobbying success is a function of the information that interest groups provide. While information has long been seen as a key aspect of lobbying success (Austen-Smith 1993; Hall and Deardorff 2006; Wright 1996), little research has directly tested the effect of information provision on lobbying success empirically. This paper offers an empirical assessment of different types of information on lobbying success in a set of five West European countries on a variety of specific policy issues. Few studies in the US or at the EU level have either looked at information in general or at the provision of technical information only (Burstein and Hirsh 2007; Dür et al. 2015; Klüver 2011b; Tallberg et al. 2018). Given that theories of informational lobbying argue that policymakers need both expert information and information on public preferences (Nownes 2006; Wright 1996), the paper argued that in order to understand the effectiveness of informational lobbying and interest representation more generally, political information needs to be added to the equation.

The results show that actors increase their likelihood of lobbying success when they provide expert information. This confirms existing studies (Burstein and Hirsh 2007; Dür et al. 2015) but expands these insights to a cross-national context. However, contrary to the expectation that both types of information should matter, the findings highlight that lobbying success is only the result of the provision of one of them. In contrast, actors engaging in more pressure-based information provision do not increase their chance of achieving their goals across issues in the sample. So while information politics has often been seen as a weapon of the weak (Beyers 2004; Kriesi et al. 2007), the analysis illustrates that such information cannot compensate. Moreover, the effect of either type of information does not increase as demand for such information or public pressure increases.

The findings have implications for democratic interest representation. The fact that groups need expert information (instead of information on public preferences) could disadvantage those that are less well equipped to provide such information. Moreover, it could mean that policy decisions are rather made in the light of technical considerations than of what different constituents want (De Bruycker 2016). It speaks to the organisational dilemma interest groups face (cf. Berkhout et al. 2017b), i.e. the tension whether to cater to constituents or meet the demands of policymakers, which results in a more technocratic (and maybe less democratic?) form of interest representation. For interest groups it seems to be more valuable to provide expert information, potentially because its strategic value is considerably higher. Expert information is difficult to access for policymakers, and other actors not working in the respective policy field. Therefore, having such information seems to be the comparative advantage for interest groups. Moreover, the demand for information on public preferences may be lower as policymakers have other sources to acquire such knowledge, which makes the strategic value of this type of information lower. Nevertheless, interest groups employ various strategies when lobbying policymakers and may consider expertise-information supply as most efficient to also represent their constituents’ interest. For example, advocates may simply frame their constituents’ demands in a much more technical way to convince policymakers of their preferred direction. As this paper shows, they are well advised to provide expert information to be successful.

Notes

Denmark: Politiken and Jyllands-Posten; Germany: Sueddeutsche Zeitung and Frankfurther Allgemeine Zeitung; Netherlands: De Volkskrant and NRC Handelsblad; Sweden: Dagens Nyheter and Svenska Dagbladet; United Kingdom: The Guardian and The Telegraph.

One could argue that it may be difficult for survey respondents to clearly distinguish between the two types of information as technical arguments can also include a normative judgment. De Bruycker (2016) compares how often interview respondents indicated to have used different information types to how often such information types have been identified using hand-coding and comes to the same conclusion, which suggests that respondents can identify different information types.

This resembles a measure used by Dür and Mateo (2013) to calculate the relative inside strategy compared to outside strategies by interest groups.

As an indicator of the extent to which the actor could rely on public expressions of support, one could potentially also use a variable asking how important respondents considered organising protests or other activities mobilising the public. All analyses have been run using such an alternative measure instead, which, however, does not alter the results (see Appendix H in Supplemental Online Material).

An intercoder reliability test on the same sample resulted in a Krippendorff’s alpha of 0.92 in distinguishing these different actor types (effective n = 50, 2 raters).

See Appendix E for alternative model specification in Supplemental Online Material.

The correlation between these two variables is 0.52, but not problematic (Vif < 2).

References

Ainsworth, S. 1993. Regulating lobbyists and interest group influence. The Journal of Politics 55(1): 41–56.

Austen-Smith, D. 1993. Information and influence: Lobbying for agendas and votes. American Journal of Political Science 37(3): 799–833.

Austen-Smith, D., and J.R. Wright. 1992. Competitive lobbying for a legislator’s vote. Social Choice and Welfare 9(3): 229–257.

Baumgartner, F.R., J.M. Berry, M. Hojnacki, B.L. Leech, and D.C. Kimball. 2009. Lobbying and policy change: Who wins, who loses, and why. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Berkhout, J. 2013. Why interest organizations do what they do: Assessing the explanatory potential of ‘exchange’ approaches. Interest Groups & Advocacy 2(2): 227–250.

Berkhout, J., J. Beyers, C. Braun, M. Hanegraaff, and D. Lowery. 2017a. Making inference across mobilisation and influence research: Comparing top-down and bottom-up mapping of interest systems. Political Studies 66(1): 43–62.

Berkhout, J., M. Hanegraaff, and C. Braun. 2017b. Is the EU different? Comparing the diversity of national and EU-level systems of interest organisations. West European Politics 40(5): 1109–1131.

Beyers, J. 2004. Voice and access political practices of European interest associations. European Union Politics 5(2): 211–240.

Binderkrantz, A.S., and A. Rasmussen. 2015. Comparing the domestic and the EU lobbying context: Perceived agenda-setting influence in the multi-level system of the European Union. Journal of European Public Policy 22(4): 552–569.

Bouwen, P. 2002. Corporate lobbying in the European Union: The logic of access. Journal of European Public Policy 9(3): 365–390.

Bouwen, P. 2004. Exchanging access goods for access: A comparative study of business lobbying in the European Union institutions. European Journal of Political Research 43(3): 337–369.

Bunea, A. 2013. Issues, preferences and ties: Determinants of interest groups’ preference attainment in the EU environmental policy. Journal of European Public Policy 20(4): 552–570.

Burstein, P. 2014. American public opinion, advocacy, and policy in Congress: What the public wants and what it gets. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Burstein, P., and C.E. Hirsh. 2007. Interest organizations, information, and policy innovation in the US Congress. Sociological Forum 22(2): 174–199.

Chalmers, A.W. 2011. Interests, influence and information: Comparing the influence of interest groups in the European Union. Journal of European Integration 33(4): 471–486.

Dahl, R.A. 1961. Who governs? Democracy and power in an American City. New Haven: Yale University Press.

De Bruycker, I. 2016. Pressure and expertise: Explaining the information supply of interest groups in EU legislative lobbying. Journal of Common Market Studies 54(3): 599–616.

Dür, A. 2008a. Interest groups in the European Union: How powerful are they? West European Politics 31(6): 1212–1230.

Dür, A. 2008b. Measuring interest group influence in the EU a note on methodology. European Union Politics 9(4): 559–576.

Dür, A., P. Bernhagen, and D. Marshall. 2015. Interest group success in the European union when (and why) does business lose? Comparative Political Studies 48(8): 951–983.

Dür, A., and G. Mateo. 2013. Gaining access or going public? Interest group strategies in five European countries. European Journal of Political Research 52(5): 660–686.

Eising, R., and F. Spohr. 2017. The more, the merrier? Interest groups and legislative change in the public hearings of the German parliamentary committees. German Politics 26(2): 314–333.

Gilens, M. 2012. Affluence and influence: Economic inequality and political power in America. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Gilligan, T.W., and K. Krehbiel. 1989. Asymmetric information and legislative rules with a heterogeneous committee. American Journal of Political Science 33(2): 459–490.

Gray, V., D. Lowery, M. Fellowes, and A. McAtee. 2004. Public opinion, public policy, and organized interests in the American states. Political Research Quarterly 57(3): 411–420.

Hall, R.L., and A.V. Deardorff. 2006. Lobbying as legislative subsidy. American Political Science Review 100(01): 69–84.

Jahn, D. 2016. Changing of the guard: trends in corporatist arrangements in 42 highly industrialized societies from 1960 to 2010. Socio-Economic Review 14(1): 47–71.

Klüver, H. 2011a. The contextual nature of lobbying: Explaining lobbying success in the European Union. European Union Politics 12(4): 483–506.

Klüver, H. 2011b. Lobbying in coalitions: Interest group influence on European Union policy-making. Nuffield’s Working Papers Series in Politics 4: 1–38.

Kriesi, H., A. Tresch, and M. Jochum. 2007. Going public in the European Union: Action repertoires of Western European collective political actors. Comparative Political Studies 40(1): 48–73.

Lohmann, S. 1998. An information rationale for the power of special interests. American Political Science Review 92(4): 809–827.

Lowi, T.J. 1964. American business, public policy, case-studies, and political theory. World Politics 16(04): 677–715.

Mahoney, C. 2008. Brussels versus the beltway: Advocacy in the United States and the European Union. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

Marchetti, K. 2015. The use of surveys in interest group research. Interest Groups & Advocacy 4(3): 272–282.

Mayhew, D.R. 1974. Congress: The electoral connection. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Michalowitz, I. 2004. EU lobbying-principals, agents and targets: Strategic interest intermediation in EU policy-making. Münster: Lit Verlag.

Nownes, A.J. 2006. Total lobbying: What lobbyists want (and how they try to get it). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Nownes, A.J., and A.J. Newmark. 2016. The information portfolios of interest groups: An exploratory analysis. Interest Groups & Advocacy 5(1): 57–81.

Pedersen, H.H. 2013. Is measuring interest group influence a mission impossible? The case of interest group influence in the Danish parliament. Interest Groups & Advocacy 2(1): 27–47.

Rasmussen, A., B.J. Carroll, and D. Lowery. 2014. Representatives of the public? Public opinion and interest group activity. European Journal of Political Research 53(2): 250–268.

Rasmussen, A., L.K. Mäder, and S. Reher. 2018. With a little help from the people? The role of public opinion in advocacy success. Comparative Political Studies 51(2): 139–164.

Schattschneider, E. 1960. The Semi-Sovereign People. A realist’s view of democracy in America. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Tallberg, J., L.M. Dellmuth, H. Agné, and A. Duit. 2018. NGO influence in international organizations: Information, access and exchange. British Journal of Political Science 48(1): 213–238.

Truman, D.B. 1951. The governmental process: Political interests and public opinion. New York: Knopf.

Wright, J.R. 1996. Interest groups and Congress: Lobbying, contributions, and influence. London: Pearson Education.

Yackee, J.W., and S.W. Yackee. 2006. A bias towards business? Assessing interest group influence on the US bureaucracy. The Journal of Politics 68(1): 128–139.

Acknowledgements

Funding was provided by Det Frie Forskningsråd (DK) (Grant No. Sapere Aude Grant/0602-02642B) and Nederlandse Organisatie voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (Grant No. VIDI Grant/452-12-008). The author would like to thank Anne Rasmussen, Wiebke Marie Junk and Jeroen Romeijn for their valuable advice and support. She would also like to thank Adrià Albareda, Ellis Aizenberg, Iskander de Bruycker, Marcel Hanegraaff, Moritz Müller, Patrick Statsch. The manuscript also benefitted from comments received at the ECPR General conference 2018, Hamburg as well as the NIG conference 2018, Den Haag. Finally, the author wishes to thank several GovLis student assistants for their contributions to the data collection.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Flöthe, L. Technocratic or democratic interest representation? How different types of information affect lobbying success. Int Groups Adv 8, 165–183 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41309-019-00051-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41309-019-00051-2