Abstract

Motivated by increasing trade and fragmentation of production across countries, accompanied by income convergence by many emerging economies, we build a dynamic two-country model featuring sequential, multi-stage production and capital accumulation. As trade costs decline over time, global-value-chain (GVC) trade expands across countries, particularly more in the faster-growing country, consistent with the empirical pattern. Via Heckscher–Ohlin forces, GVC trade can generate back-and-forth feedback between comparative advantage and capital accumulation (growth). Moreover, GVC trade increases both steady-state and dynamic gains from trade.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We employ a similar method as in Ravikumar et al. (2019) to compute the transitional dynamics in the open economy.

For instance, with two countries and three stages, the set of 8 possible chains is given by \({\mathcal {C}}=\) \(\{(1,1,1);\) (1, 1, 2); (1, 2, 1); (1, 2, 2) (2, 1, 1); (2, 1, 2); (2, 2, 1); \((2,2,2)\}\). Another example is three countries and two stages, and then, the set consists of 9 chains: \({\mathcal {C}}=\{(1,1); (1,2); (1,3); (2,1); (2,2); (2,3); (3,1); (3,2); (3,3)\}\).

The assumption of a unit location is without loss of generality, because country-stage-time efficiency differences that are common to all varieties are captured by \(A^s_{\ell ^s,t}\). In our framework, for a given country in a given time period, \(\prod _{s=1}^{S}\left[ a_{\ell }(v)\left( A^s_{\ell ^s}\right) ^{\gamma ^{s}}\right] ^{{\widetilde{\gamma }}^{s}}\) corresponds to \(\prod _{n=1}^{N}(a_{l(n)}^{n}(z))^{-\alpha _{n}\beta _{n}}\) in Antràs and de Gortari (2020). Antràs and de Gortari (2020) show that the lead-firm approach is isomorphic to an alternative framework with stand-alone producers of different stages making cost-minimizing sourcing decisions for their input in a decentralized manner, with additional assumptions on information available to producers at each stage about the exact costs of producers at earlier stages. We describe our model using only the lead-firm approach.

The usual restriction requires that \((1-\eta )/\theta >-1\), beyond which \(\eta\) plays no substantial role.

Cuñat and Maffezzoli (2007) study trade liberalization in which countries start out with permanent differences in TFP and initially different capital–labor ratios. In this scenario, countries diverge in their investment path, as the country with the higher initial capital–labor ratio accumulates capital, while the other country decumulates capital.

\(1-\text {DCE}_{n,t}\) is a generalization of the “VS” measure from Hummels et al. (2001).

More precisely, there exists a mapping from a multi-sector version of our model to an input–output table. However, as discussed and proved in de Gortari (2019), there is no unique mapping from an input–output table to a GVC model with more than two stages of production.

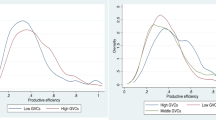

For the no-GVC case, the DCE is of course equal to one, and thus omitted from the figure.

As mentioned above, the Johnson and Noguera (2012) measure of VAX is similar to our measure of DCE.

Caselli et al. (2020) study the effects of increased openness and exposure to global shocks and find that international trade, through its diversification channel, can lead to lower income volatility.

References

Alvarez, Fernando. 2017. Capital Accumulation and International Trade. Journal of Monetary Economics 91(C): 1–18.

Antràs, Pol, and Davin Chor. 2013. Organizing the Global Value Chain. Econometrica 81(6): 2127–2204.

Antràs, Pol, Davin Chor, Thibault Fally, and Russell Hillberry. 2012. Measuring the Upstreamness of Production and Trade Flows. American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings 102(3): 412–416.

Antràs, Pol, and Alonso de Gortari. 2020. On the Geography of Global Value Chains. Econometrica 88(4): 1553–1598.

Arkolakis, Costas, Arnaud Costinot, and Andrés Rodríguez-Clare. 2012. New Trade Models, Same Old Gains? American Economic Review 102(1): 94–130.

Atkeson, Andrew and Patrick J. Kehoe. 1998. Paths of Development for Early- and Late-Bloomers in a Dynamic Heckscher-Ohlin Model. Working paper, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Staff Report 256.

Bai, Yan, and Jing Zhang. 2010. Solving the Feldstein-Horioka Puzzle with Financial Frictions. Econometrica 78(2): 603–632.

Bajona, Claustre, and Timothy J. Kehoe. 2010. Trade, Growth, and Convergence in a Dynamic Heckscher–Ohlin Model. Review of Economic Dynamics 13: 487–513.

Caliendo, Lorenzo. 2011. On the Dynamics of the Heckscher–Ohlin Theory. Working paper, Yale University.

Caliendo, Lorenzo, and Fernando Parro. 2015. Estimates of the Trade and Welfare Effects of NAFTA. Review of Economic Studies 82(1): 1–44.

Caselli, Francesco, Miklós Koren, Milan Lisicky, and Silvana Tenreyro. 2020. Diversification Through Trade. Quarterly Journal of Economics 135(1): 449–502.

Connolly, Michelle, and Kei-Mu. Yi. 2015. How Much of South Korea’s Growth Miracle Can be Explained by Trade Policy. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 7(4): 188–221.

Costinot, Arnaud, Jonathan Vogel, and Su. Wang. 2013. An Elementary Theory of Global Supply Chains. The Review of Economic Studies 80(1): 109–144.

Cuñat, Alejandro, and Marco Maffezzoli. 2004. Neoclassical Growth and Commodity Trade. Review of Economic Dynamics 7: 707–736.

Cuñat, Alejandro, and Marco Maffezzoli. 2007. Can Comparative Advantage Explain the Growth of World Trade? Economic Journal 117: 583–602.

Daudin, Guillaume, Christine Rifflart, and Danielle Schweisguth. 2011. Who Produces for Whom in the World Economy? Canadian Journal of Economics 44(4): 1403–1437.

de Gortari, Alonso. 2019. Disentangling Global Value Chains. Working paper.

Eaton, Jonathan, and Samuel Kortum. 2002. Technology, Geography, and Trade. Econometrica 70(5): 1741–1779.

Eaton, Jonathan, Brent Neiman, and Samuel Kortum. 2016. Obstfeld and Rogoff’s International Macro Puzzles: A Quantitative Assessment. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 72: 5–26.

Eaton, Jonathan, Brent Neiman, John Romalis, and Samuel Kortum. 2016. Trade and the Global Recession. American Economic Review 106(11): 3401–3438.

Fally, Thibault, and Russell Hillberry. 2015. A Coasian Model of International Production Chains. Journal of International Economics 114: 299–315.

Heathcote, Jonathan, and Fabrizio Perri. 2002. Financial Autarky and International Business Cycles. Journal of Monetary Economics 49: 601–627.

Hummels, David, Jun Ishii, and Kei-Mu. Yi. 2001. The Nature and Growth of Vertical Specialization in World Trade. Journal of International Economics 54(1): 75–96.

Johnson, Robert C. and Andreas Moxnes. 2019. GVCs and Trade Elasticities with Multistage Production. Working paper.

Johnson, Robert C., and Guillermo Noguera. 2012. Accounting for Intermediates: Production Sharing and Trade in Value Added. Journal of International Economics 82(2): 224–236.

Johnson, Robert C., and Guillermo Noguera. 2017. A Portrait of Trade in Value-Added over Four Decades. Review of Economics and Statistics 99(5): 896–911.

Kee, Hiau Looi, and Heiwai Tang. 2016. Domestic Value Added in Exports: Theory and Firm Evidence from China. American Economic Review 106(6): 1402–1436.

Koopman, Robert, Zhi Wang, and Shang-Jin. Wei. 2014. Tracing Value-Added and Double Counting in Gross Exports. American Economic Review 104(2): 459–494.

Lee, Eunhee, and Kei-Mu. Yi. 2018. Global Value Chains and Inequality with Endogenous Labor Supply. Journal of International Economics 115: 223–241.

Levchenko, Andrei A., and Jing Zhang. 2016. The Evolution of Comparative Advantage: Measurement and Welfare Implications. Journal of Monetary Economics 78(C): 96–111.

Los, Bart, Marcel P. Timmer, and Gaaitzen J. de Vries. 2016. Tracing Value-Added and Double Counting in Gross Exports: Comment. American Economic Review 106(7): 1958–1966.

Lucas, Robert E. 2003. Macroeconomic Priorities. American Economic Review 93(1): 1–14.

OECD. 2019. OECD Trade in Value-Added (TIVA) Database. Manuscript: OECD.

Ravikumar, B., Ana Maria Santacreu, and Michael Sposi. 2019. Capital Accumulation and Dynamic Gains from Trade. Journal of International Economics 119: 93–110.

Simonovska, Ina, and Michael E. Waugh. 2014. The Elasticity of Trade: Estimates and Evidence. Journal of International Economics 92(1): 34–50.

Timmer, Marcel P., Bart Los, Robert Stehrer, and Gaaitzen J. de Vries. 2021. Supply Chain Fragmentation and the Global Trade Elasticity: A New Accounting Framework. IMF Economic Review. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41308-021-00134-8.

Ventura, Jaume. 1997. Growth and Interdependence. Quarterly Journal of Economics 112(1): 57–84.

Wang, Zhi, Shang-Jin Wei, Xinding Yu, and Kunfu Zhu. 2017. Measures of Participation in Global Value Chains and Global Business Cycles. Working Paper 23222, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Yi, Kei-Mu. 2003. Can Vertical Specialization Explain the Growth of World Trade? Journal of Political Economy 111(1): 52–102.

Yi, Kei-Mu. 2010. Can Multistage Production Explain the Home Bias in Trade? American Economic Review 100(1): 364–393.

Acknowledgements

We thank the guest editor and referees for excellent comments and Robert Johnson for sharing his data on value-added exports. We also thank participants at the Virtual ITM seminar, World Bank, Malaysia, Yale Cowles Foundation Trade Conference, and the SAET conference for their comments. The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Federal Reserve Banks of Chicago, Dallas, or the Federal Reserve System.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.