Abstract

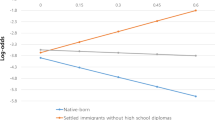

This study uses the 2013–2017 American Community Survey to explore differences in the returns to obtaining US citizenship for immigrants from the four largest source countries relative to all other immigrants. We find that Chinese, Mexican, and Filipino immigrants face a wage penalty prior to naturalization, while Indian immigrants experience higher wages than other immigrants. Naturalization more than offsets the wage penalty for Chinese and Filipino immigrants and partially offsets the wage penalty for Mexican immigrants. However, naturalized Indian immigrants earn less than non-naturalized Indian immigrants. We find only limited evidence of a naturalization premium for immigrants from other countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Third country nationals refer to countries outside of the EU that do not have bilateral labor agreements with Germany.

Estimates that include part-time workers, as well as for female workers, yield similar results. These results are available upon request.

For ease of exposition, we exclude these results from the tables below. In general, we find real earnings were higher for respondents in the 2015–2017 survey years, relative to 2013. Additionally, we find cohorts entering after 1980 earn 10–20% less than those entering prior to 1980. These results are consistent with prior findings by Borjas (1995). Our main findings are robust to inclusion/exclusion of survey-year and cohort fixed effects.

A fully interacted model, available upon request, indicates significant differences between the effects of several covariates across countries.

For ease of exposition, we withhold coefficient estimates for the other control variables from the table. These results are available upon request.

References

Akbari, Ather H. 2008. Immigrant Naturalization and Its Impacts on Immigrant Labour Market Performance And Treasury. In The Economics of Citizenship, ed. Pieter Bevelander and Don J. DeVoretz, 127–154. Holmbergs: MIM/Malmö University.

Aly, Ashraf E.-A., and James F. Ragan Jr. 2010. Arab Immigrants in the United States: How and Why Do Returns to Education Vary By Country of Origin? Journal of Population Economics 23: 519–538.

Borjas, George. 1985. Changes in Cohort Quality, and the Earnings of Immigrants. Journal of Labor Economics 3(4): 463–489.

Borjas, George. 1995. Assimilation and Changes in Cohort Quality Revisited: What Happened to Immigrant Earnings in the 1980’s? Journal of Labor Economics 13(2): 201–245.

Bratsberg, Bernt, James F. Ragan Jr., and Zafar M. Nasir. 2002. The Effect of Naturalization on Wage Growth: a Panel Study of Young Male Immigrants. Journal of Labor Economics 20(3): 568–597.

Chiswick, Barry. 1978. The Effect of Americanization on the Earnings of Foreign-born Men. Journal of Political Economy 86(5): 897–921.

Chiswick, Barry. 1986. Is the New Immigration Less Skilled than the Old? Journal of Labor Economics 4(2): 168–192.

Coon, Michael, and Miao Chi. 2018. Visa Wait Times and Future Earnings: Evidence from the National Survey of College Graduates. Journal of Economics, Race, and Policy.. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41996-018-0024-6.

Corluy, Vincent, Ive Marx, and Gerlinde Verbist. 2011. Employment Chances and Changes of Immigrants in Belgium: The Impact of Citizenship. International Journal of Comparative Sociology 52(4): 350–368.

DeVoretz, Don J., and Sergiy Pivnenko. 2005. The Economic Causes and Consequences of Canadian Citizenship. Journal of International Migration and Integration 6(3): 435–468.

Duleep, Harriet O., and Mark C. Regets. 1997. Measuring Immigrant Wage Growth Using Matched CPS Files. Demography 43(2): 239–249.

Euwals, Rob, Jacob Dagevos, Mérove Gisberts, and Hans Roodenburg. 2010. Citizenship and Labor Market Position: Turkish Immigrants in Germany and the Netherlands. International Migration Review 44(3): 513–538.

Gathmann, Christina, and Nicolas Keller. 2013. Returns to Citizenship: Evidence from Germany’s Immigration Reform. CESifo Working Paper Series No. 4738.

Helgertz, Jonas, Pieter Bevelander, and Anna Tegunimataka. 2014. Naturalization and Earnings: a Denmark-Sweden Comparison. European Journal of Population 30(3): 337–359.

Lalonde, Robert J., and Robert H. Topel. 1992. The Assimilation of Immigrants in the US Labor Market. In Immigration and the Workforce: Economic Consequences for the United States and Source Areas, ed. George J. Borjas and Richard B. Freeman, 67–92. Chicago, Il: University of Chicago Press.

Lin, Carl. 2013. Earnings Gap, Cohort Effect and Economic Assimilation of Immigrants from Mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan in the United States. Review of International Economics 21(2): 249–265.

Mazzolari, Francesca. 2009. Dual Citizenship Rights: Do They Make More and Rcher Citizens? Demography 16(1): 169–191.

Pew Research Center. 2015. Modern Immigration Wave Brings 59 Million to U.S., Driving Population Growth and Change Through 2065: Views of Immigration’s Impact on U.S. Society Mixed. Washington, D.C.

Passel, Jefferey, and D’Vera Cohn. 2019. U.S. Unauthorized Immigrants Are More Proficient in English, More Educated than a Decade Ago. Retreived July 25, 2019 from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/05/23/u-s-undocumented-immigrants-are-more-proficient-in-english-more-educated-than-a-decade-ago/.

Reserve Bank of India. 2017. Foreign Exchange Management (Acquisition and Transfer of Immovable Property in India) Regulations, 2000. Retrieved from Foreign Exchange Management Act Notification: https://www.rbi.org.in/scripts/BS_FemaNotifications.aspx?Id=175.

Ruggles, Steven, Sarah Flood, Ronald Goeken, Josiah Grover, Erin Meyer, Jose Pacas, and Matthew Sobek. 2019. Integrated Public Use Microdata Series: Version 9.0. University of Minnesota. Retrieved July 17, 2019, from http://www.ipums.org.

Scott, Kirk. 2008. The Economics of Citizenship: Is There a Naturalization Effect? In The Economics of Citizenship, ed. Pieter Bevelander and Don J. DeVoretz, 107–125. Holmbergs: MIM/Malmö University.

Steinhardt, Max F. 2012. Does Citizenship Matter? The Economic Impact of Naturalizations in Germany. Labour Economics 19(6): 813–823.

US Department of Homeland Security. 2015. Yearbook of Immigration Statistics. Retrived from https://www.dhs.gov/immigration-statistics/yearbook.

US Department of Homeland Security. 2019. Lawful Permanent Residents Data Tables. Retrived from https://www.dhs.gov/immigration-statistics/lawful-permanent-residents.

US Department of State. 2016. Annual Report of Immigrant Visa Applicants in the Family-sponsored and Employment-based preferences Registered at the National Visa Center. Retrieved from https://travel.state.gov/content/dam/visas/Statistics/Immigrant-Statistics/WaitingListItem.pdf.

US Department of State. 2019. Visa Bulletin for June 2019. Retrieved from https://travel.state.gov/content/travel/en/legal/visa-law0/visa-bulletin/2019/visa-bulletin-for-july-2019.html.

USCIS. 2016a. Citizenship Through Naturalization. Retrieved from U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services: https://www.uscis.gov/us-citizenship/citizenship-through-naturalization.

USCIS. 2016b. Per Country Limit. Retrieved from U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services: https://www.uscis.gov/tools/glossary/country-limit.

USCIS. 2016c. Visa Availability and Priority Dates. Retrieved from U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services: https://www.uscis.gov/green-card/green-card-processes-and-procedures/visa-availability-and-priority-dates.

Wahba, Jackline. 2015. Who Benefits from Return Migration to Developing Countries? IZA World of Labor, 1–10.

Wu, Yujie, and Michael C. Seeborg. 2012. Economic Assimilation of Mexican and Chinese Immigrants in the United States: Is There Wage Convergence? Economics Bulletin 32(3): 1978–1991.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chi, M., Coon, M. Variations in Naturalization Premiums by Country of Origin. Eastern Econ J 46, 102–125 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41302-019-00149-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41302-019-00149-0