Abstract

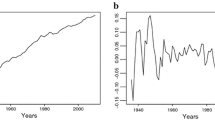

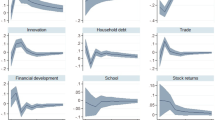

We empirically investigate the linkages between income inequality and the shadow economy. Employing a panel vector autoregression model, we build impulse response functions to study the time path of income inequality following a shock to the shadow economy, and vice versa. Our results using panel data for 144 countries over the period 1960–2009 reveal a bidirectional positive relationship between the two: specifically, higher income inequality promotes the spread of the shadow economy while the development of the shadow economy contributes to income inequality. Overall, these findings withstand a variety of robustness checks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The relationship between inequality and growth may depend on the level of development as described by the infamous Kuznets curve (see Kuznets 1955).

Z. M. Beddoes, “For richer, for poorer”, The Economist, 13 October 2012.

The shadow economy includes economic activity that is unregistered in the official economy.

Previous studies that examine the relationship between growth and inequality focus on only one sector of the economy, that is, the official sector, while neglecting the unofficial sector. Indeed, Schneider (2005, 2010) argued that the official economy could never run efficiently without the unofficial economy. Therefore, the shadow economy could be the missing link to better understand the ambiguous relationship between inequality and growth in the official economy.

Furthermore, Chong and Gradstein (2007, p. 165) argue that “this effect is magnified by poor institutional quality, which enhances the difference in rent seeking investments between the rich and the poor.”

See also Kim (2005) who shows that lower income participants are more likely to operate in the shadow sector.

Before estimation, it is imperative to test the stationarity properties of the data. To do this we used the Fisher-type panel unit root test based on the Phillips–Perron test under the null hypothesis that all panels contain a unit root against the alternative that at least one panel is stationary (with and without correcting for cross-sectional dependence). Based on the inverse Chi-squared test, the null hypothesis is rejected for each variable. These results are available upon request.

This transformation is also useful when the dataset contains many missing values.

With an unrestricted maximum lag length the AIC (BIC) chooses 16 (9) lags resulting in 144 (81) parameters to be estimated. Therefore, to prevent this overparameterization, we restrict the maximum lag length to 3.

The observations vary across the different models estimated depending on data availability.

As a word of caution, our main shadow measure is indirectly a function of GDP; however, the use of lagged values in the panel VAR models mitigates problems with this sort of identification issue.

For a fascinating and comprehensive review of entrepreneurship and the “hidden enterprise culture” in the informal economy, see Williams (2006).

The coefficient estimates are likely highly collinear; thus, the reader is advised to exercise caution when interpreting these results (see Enders 2010).

Readers are encouraged to exercise caution when interpreting the results as there is likely inequality present within the shadow economy as well. We thank an anonymous referee for pointing this out.

In addition to the following robustness checks, we also checked to ensure our results were not sensitive to the global shock related to the Great Recession (2008–2009). To do this, we restricted the time period to 1960–2007 and re-estimated the baseline model. These results are consistent with our baseline results and available upon request.

Furthermore, we account for the influence of tax revenue (as a percent of GDP) from the World Development Indicators of the World Bank (2015). Specifically, we re-estimate Eq. (1) with the vector Y containing the following variables (in specific causal ordering): lgdp, tax, inequality (market), and shadow. We also include inequality (net) in place of inequality (market) in the system. The impulse response functions illustrate that income inequality promotes the shadow economy (particularly in the system that includes inequality (net)) while the reverse effect is insignificant. These results are available upon request.

We also employed an alternate measure of institutional quality, specifically a measure of democracy from Marshall et al. (2017). The impulse response functions continue to show a positive bidirectional relationship between income inequality and the shadow economy. These results are available upon request.

We also considered the measure of the shadow economy by Alm and Embaye (2013) using the currency demand approach. While the positive effect of the shadow on inequality is present, the effect of inequality on the shadow economy is actually negative and significant. This difference is likely because this measure is most closely tied to the use of cash underground, whereas the other two measures can be viewed as more broad measures of shadow activities (e.g., including barter). These results are available upon request.

References

Aghion, P., E. Caroli, and C. Garcia-Penalosa. 1999. Inequality and economic growth: The perspective of the new growth theories. Journal of Economic Literature 37(4): 1615–1660.

Ahmed, E., J.B. Rosser Jr., and M.V. Rosser. 2007. Income inequality, corruption, and the non-observed economy: A global perspective. In Complexity Hints for Economic Policy, ed. M. Salzano and D. Colander, 233–252. Milan: Springer.

Alm, J., and A. Embaye. 2013. Using dynamic panel methods to estimate shadow economies around the world, 1984–2006. Public Finance Review 41(5): 510–543.

Asea, P.K. 1996. The informal sector: Baby or bath water? A comment. Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy 45: 163–171.

Bajada, C., and F. Schneider. 2009. Unemployment and the shadow economy in the OECD. Revue Économique 60(5): 1033–1067.

Berdiev, A.N., C. Pasquesi-Hill, and J.W. Saunoris. 2015. Exploring the dynamics of the shadow economy across US states. Applied Economics 47(56): 6136–6147.

Berdiev, A.N., and J.W. Saunoris. 2016. Financial development and the shadow economy: A panel VAR analysis. Economic Modelling 57: 197–207.

Berdiev, A. N., R. K. Goel, and J. W. Saunoris. 2018. Corruption and the shadow economy: One-way or two-way street? The World Economy, forthcoming.

Binelli, C. 2016. Wage inequality and informality: Evidence from Mexico. IZA Journal of Labor and Development 5(5): 1–18.

Binelli, C., and O. Attanasio. 2010. Mexico in the 1990s: The main cross-sectional facts. Review of Economic Dynamics 13(1): 238–264.

Birinci, S. 2013. Trade openness, growth, and informality: Panel VAR evidence from OECD economies. Economics Bulletin 33(1): 694–705.

Chong, A., and M. Gradstein. 2007. Inequality and informality. Journal of Public Economics 91(1–2): 159–179.

Dabla-Norris, E., K. Kochhar, N. Suphaphiphat, F. Ricka, and E. Tsounta. 2015. Causes and consequences of income inequality: A global perspective. IMF Staff Discussion Note, June 2015, SDN/15/13.

Dell’Anno, R., and O.H. Solomon. 2008. Shadow economy and unemployment rate in USA: Is there a structural relationship? An empirical analysis. Applied Economics 40(19): 2537–2555.

Dell’Anno, R., and O.H. Solomon. 2014. Informality, inequality, and ICT in transition economies. Eastern European Economics 52(5): 3–31.

Dessy, S., and S. Pallage. 2003. Taxes, inequality and the size of the informal sector. Journal of Development Economics 70(1): 225–233.

Dreher, A., C. Kotsogiannis, and S. McCorriston. 2009. How do institutions affect corruption and the shadow economy? International Tax and Public Finance 16(6): 773–796.

Eilat, Y., and C. Zinnes. 2002. The shadow economy in transition countries: Friend or foe? A policy perspective. World Development 30(7): 1233–1254.

Elgin, C., and O. Öztunali. 2012. Shadow economies around the world: Model based estimates. Working paper.

Enders, W. 2010. Applied Econometrics Time Series. 3rd ed. New York: Wiley.

Feige, E.L. 1989. The Underground Economies: Tax Evasion and Information Distortion. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Foellmi, R., and J. Zweimüller. 2011. Exclusive goods and formal-sector employment. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 3(1): 242–272.

Gërxhani, K. 2004. The informal sector in developed and less developed countries: A literature survey. Public Choice 120(3–4): 267–300.

Gutiérrez-Romero, R. 2010. The Dynamics of the Informal Economy. CSAE WPS/2010-07. Oxford: Oxford University.

Hamilton, J.D. 1994. Time Series Analysis. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Hatipoglu, O., and G. Ozbek. 2011. On the political economy of the informal sector and income redistribution. European Journal of Law and Economics 32(1): 69–87.

Hirschman, A.O. 1970. Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Holtz-Eakin, D., W. Newey, and H.S. Rosen. 1988. Estimating vector autoregressions with panel data. Econometrica 56(6): 1371–1395.

Johnson, S., D. Kaufmann, and A. Shleifer. 1997. The unofficial economy in transition. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 2: 159–239.

Kaldor, N. 1957. A model of economic growth. The Economic Journal 67(268): 591–624.

Kaufmann, D. 1997. The missing pillar of a growth strategy for Ukraine: Reforms for private sector development. In Ukraine: Accelerating the Transition to Market, ed. P.K. Cornelius and P. Lenain, 234–274. Washington: International Monetary Fund.

Kim, B.-Y. 2005. Poverty and informal economy participation: Evidence from Romania. Economics of Transition 13(1): 163–185.

Kotschy, R., and U. Sunde. 2017. Democracy, inequality, and institutional quality. European Economic Review 91: 209–228.

Krstić, G., and P. Sanfey. 2007. Mobility, poverty and well-being among the informally employed in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Economic Systems 31(3): 311–335.

Krstić, G., and P. Sanfey. 2011. Earnings inequality and the informal economy: Evidence from Serbia. Economics of Transition 19(1): 179–199.

Kuznets, S. 1955. Economic growth and income inequality. American Economic Review 45(1): 1–28.

Lazear, E.P., and S. Rosen. 1981. Rank-order tournaments as optimum labor contracts. Journal of Political Economy 89(5): 841–864.

Loayza, N.V. 1996. The economics of the informal sector: A simple model and some empirical evidence from Latin America. Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy 45: 129–162.

Love, I., and L. Zicchino. 2006. Financial development and dynamic investment behavior: Evidence from panel VAR. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance 46(2): 190–210.

Lukiyanova, A. 2015. Earnings inequality and informal employment in Russia. Economics of Transition 23(2): 469–516.

Marshall, M. G., T. R. Gurr, and K. Jaggers. 2017. Polity IV project: Political regime characteristics and transitions, 1800–2016. http://www.systemicpeace.org/inscrdata.html.

Medina, L., and F. Schneider. 2017. Shadow economies around the world: New results for 158 countries over 1991-2015. CESifo working paper no. 6430.

Mishra, A., and R. Ray. 2010. Informality, corruption, and inequality. Bath economics research paper no. 13/10. Department of Economics, University of Bath.

Ostry, J. D., A. Berg, and C. G. Tsangarides. 2014. Redistribution, inequality, and growth. IMF staff discussion note, SDN/14/02.

Rauch, J.E. 1991. Modelling the informal sector formally. Journal of Development Economics 35(1): 33–47.

Rosser Jr., J.B., and M.V. Rosser. 2001. Another failure of the Washington consensus on transition countries: Inequality and underground economies. Challenge 44(2): 39–50.

Rosser Jr., J.B., M.V. Rosser, and E. Ahmed. 2000. Income inequality and the informal economy in transition economies. Journal of Comparative Economics 28: 156–171.

Rosser Jr., J.B., M.V. Rosser, and E. Ahmed. 2003. Multiple unofficial economy equilibria and income distribution dynamics in systemic transition. Journal of Post Keynesian Economics 25(3): 425–447.

Schneider, F. 2005. Shadow economics around the world: What do we really know? European Journal of Political Economy 21(3): 598–642.

Schneider, F. 2010. The influence of public institutions on the shadow economy: An empirical investigation for OECD countries. Review of Law and Economics 6(3): 441–468.

Schneider, F. 2012. The shadow economy and work in the shadow: What do we (not) know? IZA discussion paper no. 6423.

Schneider, F., A. Buehn, and C. E. Montenegro. 2010. Shadow economies all over the world: New estimates for 162 countries from 1999 to 2007. Policy research working paper no. 5356, The World Bank.

Schneider, F., and D.H. Enste. 2000. Shadow economies: Size, causes, and consequences. Journal of Economic Literature 38(1): 77–114.

Solt, F. 2016. The standardized world income inequality database. Social Science Quarterly 97(5): 1267–1281.

Torgler, B., and F. Schneider. 2007. Shadow economy, tax morale, governance and institutional quality: A panel analysis. Working paper.

Valentini, E. 2009. Underground economy, evasion and inequality. International Economic Journal 23(2): 281–290.

Williams, C.C. 2006. The Hidden Enterprise Culture: Entrepreneurship in the Underground Economy. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Winkelried, D. 2005. Income distribution and the size of the informal sector. Working paper. St John’s College, University of Cambridge.

Wintrobe, R. 2001. Tax evasion and trust. Working paper.

World Bank. 2015. World Development Indicators. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Xue, J., W. Gao, and L. Guo. 2014. Informal employment and its effect on the income distribution in urban China. China Economic Review 31: 84–93.

Acknowledgements

We thank Cynthia Bansak (editor), four anonymous referees, and participants at the Midwest Economics Association Conference (Cincinnati), Western Economic Association International Conference (San Diego), 5th International Conference on “The Shadow Economy, Tax Evasion and Informal Labor” (Warsaw) and International Atlantic Economic Conference (Montréal) for valuable suggestions. All remaining errors are our own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Berdiev, A.N., Saunoris, J.W. On the Relationship Between Income Inequality and the Shadow Economy. Eastern Econ J 45, 224–249 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41302-018-0120-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41302-018-0120-y