Abstract

Understanding how science, technology, and innovation is produced by the UN Food Systems Summit process offers a lens into how dominant actors in global food policy continually rework their power and legitimacy. Focusing on discourses and material networks, the article shows that the Scientific Group makes appeals to inclusivity—of people of colour, women, youth, smallholders, and more—while extending old Green Revolution ideas through new 4th Industrial Revolution innovations and governance ambitions.

Similar content being viewed by others

‘Science is one lens for making sure that changes are integrated and collectively deliver better outcomes. But the task is challenging. Food spans many disciplines—not least agriculture, health, climate science, artificial intelligence and digital science, political science and economics…..A range of voices is crucial. The Scientific Group is engaging with hundreds of experts across civil society, including Indigenous peoples, producer and youth organizations and the private sectors’ (von Braun et al. 2021c: 28–29).

We wrote this article on the eve of the UN Food System Summit (UNFSS) on 23 September 2021, less than one month after the above lines were published in Nature journal. Its authors, the chair and co-chairs of the Scientific Group, an advisory committee to the Summit, were making an appeal to fellow scientists, policymakers, and the general public about the pluralistic and inclusive nature of their approach. ‘A range of voices is crucial’. Some analysts have distilled these motions to mere rhetoric or worse, lies. We suggest something more interesting, complicated, and problematic is underway. As scientists accustomed to old Green Revolution thinking and practices confront challenges to the hegemony of that approach, some boundaries are being reinforced (note the limited disciplines mentioned in the Nature passage) while others are being redrawn (note the engagements with a wider body of knowledge makers). With Green Revolution orthodoxy opening up to epistemically marginalized communities, subaltern agencies and expertises could fissure dominant worldviews—or could be tokenized and used to legitimate a renewed orthodoxy.

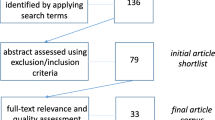

In this article, we argue that understanding how ‘science, technology, and innovation’ (STI) was used in the UNFSS process offers a lens into how dominant actors in global food policy are both perpetuating the status quo and absorbing challenges to their power. Based on document review, participant observation, and discourse analysis,Footnote 1 we trace the origins of the UNFSS ‘impetus for innovation’ through rivaling trends within the Food and Agriculture Organization dating back roughly a decade. We show how one of these trends, dovetailing with the World Economic Forum’s powerful pro-business agenda, provided the ‘innovation impetus’ for the Summit at a time of growing legitimacy for agroecology. In this context, the UNFSS can be seen as an extension of old socio-material networks and discourses of the Green Revolution order, but with greener, socially inclusive narratives that reflect and reinforce the ‘reset’ mantra of multi-stakeholder capitalism.

By tracing how the UNFSS Scientific Group has been appealing to new audiences, constructing consensus, and presenting itself as a depolarizing body, we illustrate the way that the Scientific Group has reinforced certain boundaries, while eroding others. Appealing to and involving women, people of color, and youth, it has signalled strategic reflexivity about colonial, top-down expertises that have typically bounded ‘science’. It has also courted multiple types of knowledge-making communities and presented itself as a peacemaker over contentious agricultural issues. At the same time, the Scientific Group has fastidiously preserved an expert network of economists and natural scientists, and, by fusing motifs of WEF’s 4th Industrial Revolution to the Sustainable Development Agenda, left little space for any subversion of the dominant food order. Inclusive STI, then, may serve to legitimize the continual exclusion of agroecology and food sovereignty communities, among others working for transformative food systems change. Beyond the UNFSS, this study offers a glimpse into how STI articulates with governance in preserving the historical arc of colonial hegemony while adding a veneer of sustainability and ‘empowerment’ of groups who, by this reckoning, have not yet benefited from modern agriculture.

Legitimacy, Discourse, and Material Networks

Science and Technology Studies (STS) provides the foundations for our study. Over the past few decades, STS scholars have shown how the authority of science emerges through social processes of professionally trained scientists making and validating empirical knowledge through the use of reproducible procedures and peer review (Latour and Woolgar 1979; Shapin and Schaffer 1985). They have also discussed how science is frequently used as a valuable resource in public arenas from legislatures to the mass media to gain greater legitimacy for political decisions, bureaucratic procedures, or policy institutions (Ezrahi 1990; Jasanoff 2004). Legitimacy means that knowledge or technology, for instance, is widely accepted as credible and authoritative. While legitimacy has multiple bases (e.g. legal, civic, practical), scientific validation is particularly powerful (Montenegro de Wit and Iles 2016). The prevailing hierarchy of knowledge and experts, the cumulative resources of scientific institutions, and the ingress of science deep into the workings of contemporary policy systems all greatly favour scientific and technological knowledge. Behind all these features lies the ‘boundary work’ that scientists and their allies engage in, namely drawing a rhetorical boundary between science and some less authoritative non-science by attributing certain qualities (e.g. objectivity and apoliticality) to scientists, scientific methods, and scientific claims (Gieryn 1999).

Such structural and political advantages have also fundamentally influenced how industrial food systems have developed over the past century. Industrial food is perceived as highly legitimate in part because of how scientific research and development has generated an array of technologies that together assure the reliable production of cheap food (Iles et al. 2017). Pesticides, mechanical harvesters, hybrid corn, and, now, AI-enabled robots and gene-edited plants assist farmers in subduing an unpredictable, biologically alive nature in order to meet the economic imperatives of agribusiness.

Both discourses and socio-material networks have played central roles in the ongoing legitimation of industrial food systems. Discourse is here defined as a ‘specific ensemble of ideas, concepts, and categorisations that are produced, reproduced, and transformed in a particular set of practices and through which meaning is given to physical and social realities’ (Hajer 1995: 44). Fairclough (1993: 67) emphasizes that discourses do not merely represent the world, but are a practice of ‘signifying the world, constituting and constructing the world in meaning’. Central to these processes are how discourses establish, sustain, and or change power relations between different classes, communities, and other social groups. For example, in the context of ‘development’, Escobar (2012 [1995]) traces how discourses systematically construct the subjects and worlds of which they speak: propagating modern cultural values, normalizing World Bank and IMF institutional control, and guiding technology, monetary policy, and agricultural development. This creates a discursive space within which only certain things can be said, or even imagined.

In turn, social-material networks in the food context refer to the creation of a network that combines human agents with agricultural research organizations, biological organisms, technological systems, and knowledge repositories (de Sowa and Busch 1998). Here our emphasis is on the ways diverse scientific and technical actors—and the knowledges they represent—connect to shape a movement that advances specific pathways of development (see also Latour 1993 on the advent of pasteurization in France, in which Pasteur created and mobilized a network of scientists and public officials to support the germ theory of disease and heating as a food safety solution).

The ‘long Green Revolution’ (Patel 2013) exemplifies how material networks and discourses work together to create and maintain a particular agrarian scientific order. Discourses of progress helped justify and drive the Green Revolution: starving peoples across the Global South would be fed with high-yielding rice and wheat; anachronistic peasant methods would be modernized through new seeds and agro-chemicals; scientific ingenuity would vanquish overpopulation and rescue peasants from their ‘traditional culture of poverty’ (Yapa 1993). Vanquishing red revolutions was always, of course, the collateral goal, as the US aimed to contain Soviet influence and sublimate leftist peasant revolts with the promise of full bellies (Perkins 1990; Patel 2013). Against the spectre of communism, the Green Revolution deployed Science: a large material network that consisted of cadres of policymakers, scientists, and economists trained at universities in the US and sent back to their home countries to implement technological solutions (Fitzgerald 1986; Jennings 1988). Rockefeller Foundation staff, government officials and experts, agro-chemical industry advisors, and agricultural scientists steeped in the Green Revolution paradigm further influenced countries like India and Mexico to abandon their vibrant ‘traditional’ agricultures. Simultaneously, a material infrastructure was established to transfer the new science and technology to those countries through trade, corporate investment, and development aid. These Green Revolution discourses and material networks continue to configure global food policy today.

The Innovation Imperative: A Brief History

Battles for legitimacy at FAO: Agroecology and ‘Other Innovations’

The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) has long been a contested space for global food governance (McKeon this issue). During the 1960s, Green Revolution projects promoted by the US, the FAO, the Rockefeller Foundation, and the Ford Foundation saw scientific programmes for developing high-yield seeds dovetail with a ‘food aid’ regime in which countries receiving US aid often used counterpart payments to pay for seeds, chemical, and fertilizer packages (McMichael 2008). The failure of these strategies for mitigating hunger and malnutrition prompted the FAO to launch programmes for food security in the 1970s.

But with the inadequately mandated World Food Council in charge, governments and corporations quickly began to pursue food security by promoting increased trade liberalization and the concentration of food production in the hands of fewer, and larger, agribusiness enterprises. This approach offered no real possibility for peasant movements buffeted by surplus dumping and other devastating effects of a ‘just produce and/or import more food from somewhere’ strategy (Wittman et al. 2010: 3). By 1996, La Vía Campesina and allied civil society organizations would reject food security in favor of ‘food sovereignty’, and roughly two decades later, these same movements formally embraced agroecology as a paradigm for food system change (Nyéléni 2015). Agroecology and food sovereignty were thus positioned as twin pillars of a transformation beyond the horizons that FAO and other UN institutions readily championed.

In part because of these challenges from civil society and a handful of governments, FAO began to recognize agroecology in its formal processes. A landmark International Agroecology symposium was convened by FAO in 2014 and, from 2015–2019 a global dialogue convened roughly 1350 participants from 165 countries to give their input on the potential of agroecology to transform food and agriculture (Loconto and Fouilleux 2019).Footnote 2 This ‘institutionalization’ of agroecology was not without critics—many of whom worried it could lead to cooptation and depoliticization of agroecology, defusing its potential for transformative social change (Giraldo and Rosset 2018). Yet while peasant movements and scholar-activists illuminated agroecology as territory in dispute, less debatable was that agroecology’s fulcrum of legitimacy was shifting in ways that would threaten actors not inclined to welcome ‘a new window in the Cathedral of the Green Revolution’.Footnote 3

Those actors instead sought to both undercut agroecology and promote technology-focused development paths. The First International FAO Symposium on the role of Agricultural Biotechnology was held in 2016, followed by regional events in Asia/the Pacific and sub-Saharan African in 2017. Further regional conferences were cancelled after social movements took advantage of these fora to publicly air concerns (Anderson and Maughan 2021). But proponents of biotechnology within FAO, undaunted, regrouped and started focusing instead on ‘innovation’. In parallel, some member states (especially the US) put stipulations on another process, promoted by civil society movements in the World Committee on Food Security, to initiate a High-Level Panel of Experts (HLPE) report on Agroecology. Eventually an HLPE report on agroecology was confirmed, but with the concession that the report couldn’t only be about agroecology. Rather, it should cover agroecology and ‘other innovations’.

This history, we argue, is important for avoiding overly simplified analyses of the UNFSS dynamics, where the ‘good’ FAO battles against ‘bad’ corporate interests. FAO had long held political divergences in its own ranks, sparking struggles to affirm different types of scientific and knowledge legitimacies. Agroecological and technological trends have waxed and waned relative to one another early in the twenty-first century, a balance strongly tipped by exogenous forces including government pressures, corporate power, and civil society demands. For ‘innovations’ advocates within FAO, the CGIAR had been an important partner ever since the FAO helped birth this network at the dawn of the Green Revolution. A decade into the new millennium, as the CG system buckled and underwent its own restructuring (IPES-Food 2020), opportunities for new allyships emerged: The World Economic Forum was, in fact, already suturing ‘innovations’ to ‘food systems’ in its visions for a 4th Industrial Revolution, the story to which we now turn.

The World Economic Forum’s 4th Industrial Revolution

Famed for its annual Davos convenings of plutocracy and power, the World Economic Forum has evolved into a thinktank for boosting globalization. Founded in 1971, WEF now mobilizes an intellectual empire based on its material network of sympathetic governments, companies, and civil society groups. Historically, the group laboured to propagate neoliberal ideas of free trade, economic growth, and corporate-friendly governance. Over the past 20 years, WEF embraced social and environmental causes, in response to 1990s anti-globalization protests. The Forum now promotes a strong multi-stakeholder approach, with proliferating global future councils, young global leaders, global shaper communities, platforms, and industry initiatives (Pigman 2007; Gleckman 2016). For example, in 2017, WEF launched the Platform for Accelerating the Circular Economy, a public–private partnership that assembles corporations, the United Nations Environmental Programme, Accenture, the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, and others to reduce waste production.Footnote 4 WEF now propounds an enlightened, reformed capitalism that has learned from its mistakes. Davos 2020 had a theme of ‘Stakeholders for a Cohesive and Sustainable World’, with calls to cease fossil fuel subsidies and broaden measurements of economic well-being. This nascent metamorphosis continued in 2021, with Prince Charles coming aboard to consider how to achieve ‘The Great Reset’ after the COVID-19 pandemic through a ‘stakeholder economy’.Footnote 5

The stakeholder economy is part of a larger vision for a 4th Industrial Revolution, which WEF has promoted since roughly 2017. The so-called ‘4IR’ fuses physical, digital and biological worlds with technologies that span the three. In this vision, self-driving cars, artificial intelligence, blockchain, gene editing, and robots will transform the planet and bring prosperity and sustainability for all. In the words of WEF founder and chairman Klaus Schwab, ‘[t]he world has the potential to connect billions more people to digital networks, dramatically improve the efficiency of organizations and even manage assets in ways that can help regenerate the natural environment’ (Schwab 2017: 1). However, cautions Schwab, the new technologies can create perils that must be forestalled by ‘putting people first, empowering them and constantly reminding ourselves that all of these new technologies are first and foremost tools made by people for people’ (Schwab 2017: 2). This inclusive strain continues at UNFSS, which we explore further below.

Although the 4IR did not at first mention food and agriculture, WEF soon identified this as a major arena where it could potentially intervene. It created a Food Systems Initiative, which aims to nurture ‘systems leadership’ with new mindsets and ways of working that can manage complex systems and deliver future food systems that are fit for purpose. In 2018, alongside McKinsey and Company, the forum coauthored a major report, ‘Innovation with a Purpose: The role of technology innovation in accelerating food systems transformation’ (WEF 2018). The report is remarkable in many ways. First, given widespread recognition of a need for a fundamental transformation of food systems, it assumes there is broad agreement on what this transformation looks like and calls for. Second, its major premise is that food systems have lagged in harnessing the power of new technologies and making these widely accessible. Third, such technologies are highly circumscribed to investor-friendly types: they include gene editing for multiple crop traits, precision agriculture for water and resource efficiency, alternative proteins, and mobile service delivery—all of which now feature in UNFSS discussion of relevant STI.

A Strategic Partnership in the Cathedral of the Green Revolution

In June 2019, WEF signed a strategic partnership agreement with the UN to support the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Ratifying existing collaborations, the agreement aimed ‘to help each other increase their outreach, to share networks, communities, knowledge and expertise, to foster opportunities for innovation, and to encourage a wide understanding of and support for priority issues among their relevant stakeholders’.Footnote 6 Adapting to technology-driven trends and harnessing the opportunities of multi-stakeholder engagement were viewed as key drivers of the agreement. Among other cooperative actions (mostly about giving the UN access to WEF spaces), UN Secretary-General António Guterres was invited to deliver an annual keynote talk at Davos, where he clarified the impetus for the partnership: ‘It needs to be multilateralism in which not only states are part of the system, but we need to make sure that we bring together, into this multilateral system, the voice and the influence of the business community’.Footnote 7 Noticeably, the six jointly-chosen areas of work (e.g. climate change and digital cooperation) did not initially include food systems, nor was there any reference to food and agriculture anywhere. However, the partners were empowered to consult with each other ‘on additional issues of mutual interest in which cooperation may foster their respective and collective purposes’. Evidently, WEF and the UN subsequently agreed that food systems would become a seventh area.

While WEF is only one of many actors helping develop the UNFSS, along with the UN Secretariat, it appears to have had an outsized impact on the agenda and design. The broad Summit agenda was initially sketched in 2019 through a WEF concept paper (Fakhri 2021). In November 2020, WEF held a pre-summit event, where the speakers and participants included most of the members of the Summit integrating team. This event helped define the themes and structure of the Summit itself. For example, the Summit DialoguesFootnote 8 were directly modeled on the food systems dialogues that WEF helped start in 2018 in partnership with EAT and the World Business Council for Sustainable Development. Dialogues were, however, just a microcosm of the larger borrowed approach: a multi-stakeholder model for food systems governance. As multiple academic analyses have shown, multi-stakeholderism leaves the roles of States unclear (HLPE 2018; Canfield et al. 2021), allows those with the most power and wealth to devote resources necessary to influence a given process (Fakhri 2021), and disenfranchises already-marginalized communities whose stakes are not counted in capital or other recognized currencies. For example, Clapp et al. (this issue) illustrate how corporations have exercised their power to assure that the Summit remains largely silent on market consolidation.

We argue, in turn, that science is central to generating the base of legitimacy on which multi-stakeholderism is built. Beyond merely encouraging the uptake of a 4IR vision, scientific stakeholders help craft the technologies, innovations, and evidentiary norms that have come to stand in for knowledge itself. To better understand how this scientific practice is quite the social process, we turn now to the Scientific Group, which has been central to making science into a powerful resource for legitimating the Summit and its consequences.

Science at the UNFSS

The Scientific Group

Soon after the Summit was announced, the UN Deputy Secretary-General invited Joachim von Braun to serve as the chair of a new Scientific Group that would provide expert input into the Summit’s planning. Per its terms of reference, the group was charged with ‘ensuring the Summit brings to bear the foremost scientific evidence’ and ‘ensures the robustness and independence of the science underpinning dialogue of food systems policy and investment decisions’ (SciGroup 2020). To this end, the Group would help link ongoing initiatives, including the UN system, the CFS High Level Panel of Experts, the CGIAR, science-based institutions, and ‘any other relevant knowledge that will help advance the quality of evidence for future food systems’ (SciGroup 2020). Von Braun was authorized to identify 24 members to join the Scientific Group, who would be globally renowned and come from universities, international organizations, and standards-setting bodies. Three vice-chairs were also appointed who, alongside their Scientific Group peers, were asked to serve as public spokespersons for the Summit, as well as informing Summit content and recommended outcomes. Structurally, the chair would serve on the Summit Advisory Committee (the top-level UNFSS decision-making tier) to ensure that the Group’s ideas would be conveyed to the Secretary-General.

In The Scientific Life (2009), science historian Steven Shapin delves into the lives of highly-respected scientific experts—people authorized to describe and interpret the world and to transform knowledge into power and profit. Shapin’s concern with the authority of science is not, however, about why some groups of scientists may prefer theory A while others prefer theory B. Rather, he suggests, he’s interested in ‘the conditions in which what is taken to be science is or is not considered credible, in which those responsible for the knowledge are or are not thought to be reliable sources, in which their way of life in the making of scientific knowledge is or is not reckoned to be one that conduces to the reliability of that knowledge’ (Shapin 2009: 2). It is in this sense that we are interested in the Scientific Group—not to assail anyone’s individual credibility or character but to understand the conditions under which a particular interpretation of the ‘food system’, its problems and its solutions, becomes authoritative and imbued with the power to transform material food system conditions.

Now a professor at the University of Bonn, von Braun trained in agricultural economics and has built a distinguished academic career while also leading the International Food Policy Research Institute in Washington DC between 2002 and 2009. He is also chair of the federal government Bioeconomy Council in Germany. Von Braun is not alone in the Scientific Group in being trained in economics, nor in his CGIAR connection. Of the Scientific Group’s 28 members, a full third (ten members) have doctoral degrees in either agricultural economics or economics, nine have training in the biophysical sciences, eight are specialists in food and nutrition science (food safety, food processing, food security), and two are medical doctors. At least eight members have self-declared interests in advancing agricultural biotechnology and agri-food technologies. At least eight members have worked for CGIAR centers, where Green Revolution science and technology was birthed from Cold War geopolitical tensions of the twentieth century.

A few profiles of Scientific Group members are illustrative of the material networks they comprise. Before taking on her current position as Managing Director of the CGIAR, Dr. Claudia Sadoff was Director General of the International Water Management Institute of the CGIAR and the Global Lead for Water Security and Integrated Resource Management at the World Bank where she spent nearly 25 years working in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East. She is also a member of WEF’s Global Agenda Council on Water Security. Peruvian economist Dr. Maximo Torero, currently serving in the Economic and Social Development division at FAO, until recently served at the World Bank Group in Washington, D.C. as the executive director for Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Paraguay, Peru and Uruguay. Prior to this, he led the Markets, Trade and Institutions Division at the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) of the CGIAR, where, among other things, he became renowned for his work on property rights, arguing in favor of urban and rural titling and crop choices (The Economist 2006).

Dr. Louise Fresco brings similarly strong networks and track records of policy advocacy. Invited to serve alongside von Braun as a Vice-Chair of the Scientific Group, Fresco is president of the Executive Board of Wageningen University & Research in The Netherlands. Her biography points to ‘extensive involvement’ in policy and development and features high marks of scientific legitimacy, including membership in eight Scientific Academies, four honorary doctorates, and ten years at FAO. Her CV also clearly connects public and private sector networks: Fresco is a non-Executive Director on the board of Syngenta and has previously served on supervisory boards of companies like Unilever and Rabobank, the Dutch multinational banking and financial services company (Clapp et al. this issue). Over her decorated career, Fresco has become well known for championing precision agriculture, bioscience investments, and the deregulation of biotechnology across Europe. The continent’s anti-GMO position, she has consistently argued, essentially ‘reflects a wider distrust of science’ (Fresco 2013).

Fresco is hardly alone in the Scientific Group in representing a ‘scientific life’ where corporate and academic profiles have melded, metamorphosed, and redefined the foundations for producing scientific knowledge, basic and applied. Because conflict of interest statements were not required of Scientific Group members, we did not have ready access to full COI data. But easily discoverable documents indicate that three members have been employed by the World Bank, and another handful have connections to the Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN) and the EAT-Lancet Commission, both of which serve to mobilize public private partnerships in line with their self-expressed commitments to multi-stakeholder governanceFootnote 9 and to ‘sound science, impatient disruption and novel partnerships’.Footnote 10 Indeed, members of the Scientific Group appear to have been particularly sought out for their record in establishing ‘excellent networking with the food industries, government, and professional societies on food policy formulations for education, science and technology’.Footnote 11

Certifying Knowledge, Constructing Consensus

Through its scientific advisory practices, the Scientific Group helped UNFSS organizers legitimate the Summit as a global food policy-making process. Invoking science as a powerful epistemic resource, the Group worked both implicitly and explicitly to make a case for transformative change of food systems through the 4th Industrial Revolution. This work involved an array of strategies that STS scholars have previously identified as playing an important role in making and certifying authoritative knowledge for use in policy processes, such as the Summit. Here, we focus on three interlinked aspects: staging evidence, constructing consensus, and depolarization.

Using a case study of US National Academy of Science committee reports on nutrition and dietary recommendations, Hilgartner (2000) examined the social process of how the credibility of expert advice is created and maintained through dynamic interaction between advisory groups and their audiences. He portrays the committees as performers on ‘stages’ who manage the presentation of their potentially contentious advice, by using narratives of science-as-truth, accentuating technical expertise, selectively revealing some things while hiding other things, and issuing information releases. Similarly, on the UNFSS stage, the Scientific Group attempted to build credibility in an ontologically and epistemically diverse global food space. It worked to cultivate an audience that supports its particular interpretation of science, and to justify a bridge from science-advice to policy work. Importantly, in its attempts to reach a mix of other scientists, governments, and companies, the Group also showed its awareness that science isn’t inherently persuasive just because (in its view) science is universally and objectively true. With increasingly many publics contesting the hegemony of capital, science, and the state (van der Ploeg this issue), the Scientific Group realized it had to show why science matters to food systems transformation. At the same time, the Group had to demonstrate its institutional relevance in a world where it’s unclear if old standards of science-policy governance still hold, as numerous startups and private ventures now regularly fund and put technologies into circulation.

Towards demonstrating that science matters, the Scientific Group compiled and portrayed extensive scientific evidence in support of its claims. The chair and vice-chairs were particularly active: authoring several major assessments of what the Scientific Group views as the prevailing scientific knowledge, proposing a definition of food systems (von Braun et al. 2021a), and outlining key ‘innovation priorities’ to guide the Summit’s work (von Braun et al. 2021b). Additionally, Scientific Group members produced numerous technical briefs, both alone and in tandem with the group’s ‘global partners’; they described these activities to the public as ‘helping mobilize scientific communities around the world’ (von Braun et al. 2021d).

The staging of scientific evidence was seen in multiple public and private spaces, long before the Summit itself. Early in the year, leaders of the Scientific Group, notably von Braun and Fresco, made numerous presentations at forums such as the China Agricultural University (2 June 2021), the G20 Meeting of Agricultural Chief Scientists (15 June 2021), and the World Food Convention (24 June 2021). In July, a 2-day event called ‘Science Days’ focused on ‘highlighting the centrality of science, technology and innovation for food systems transformation’.Footnote 12 In late August, the chair and vice-chairs published a commentary in Nature summarizing their priorities (von Braun et al. 2021c), and in September, one week prior to the Summit, it released a mammoth 452-page compendium, ‘The Scientific Reader’ (SciGroup 2021). In what amounted to a spectacular evidence dump, the reader collected all of the Scientific Group’s and partner’s writings to date, alongside an online bibliography of ‘relevant literature’. The accompanying press release (von Braun et al. 2021d) noted that most of the papers had been both scientifically peer-reviewed—and further evaluated by governments, civil societies, and the general public, implying the use of non-traditional extended peer review (Funtowicz and Ravetz 1993). The same release affirmed that ‘Science, technology and innovation can and must play a pivotal role in the necessary transformation of food systems’ (von Braun et al. 2021d), effectively affirming the centrality of STI through invoking public participation.

A second key focus of the Scientific Group was to cultivate the appearance of scientific consensus around its understanding of relevant innovations. To gather endorsement for technology-led, investor-friendly approaches in line with the 4IR, the Scientific Group convened events that visibly gathered leading scientists, entrepreneurs, and policymakers to sketch the STI landscape and demonstrate buy-in for its proposals. One important event was a workshop at the Pontifical Academy of Science in Vatican City on 21–22 April. Most Scientific Group members participated, along with many people who would later speak at the Science Days, Martin Rees (former president of the British Royal Society), Frances Arnold (Nobel prize-winner for chemistry), and other scientific luminaries. The workshop yielded a statement which declared, among other things, ‘science and innovation are essential to accelerate the transformation to more desirable food systems’.Footnote 13 The ‘Science Days’ event also aimed to orchestrate consensus on what needs to be done. The presence of the Director General of the FAO, the chairperson of the Committee for World Food Security, the editor-in-chief of Nature journal, and several national science academy members and World Food Prize winners suggested world-class expert endorsement for a simple vision: that the answers lie in ‘unlocking the potential’ for STI to catalyze food system transformation (see Fig. 1). In many ways, the Scientific Group was the most publicly visible part of the UNFSS organizing process, an effect it amplified through self-advertisement: ‘The event brought together more than 2,000 participants from research, policy, civil society and industry…’ (Science Days 2021). These combined efforts attest to the active work of legitimating the 4IR vision that animated the Summit.

Third, the emphasis on creating science-based consensus was linked to a discourse of depolarization. Here, the Scientific Group portrayed itself as acting as a peacemaker via science, suggesting that heated contestations—for example, over the role of biotechnology in agriculture—can and should be defused. For example, a key Science Days panel asked: ‘Why the fight? Getting to grips with missed opportunities and contentious issues in science and innovation for food systems’. Four panelists were invited to discuss how contemporary science might help reconcile tensions and move beyond polarization (Fig. 2). Critical observers, however, would quickly recognize old tropes in new skins. Headlined by David Zilberman, a UC Berkeley agricultural economist with a record of lambasting critics of GM crops and praising Monsanto for its business acumen,Footnote 14 the panel suggested that only uninformed, emotional people (lacking the cool reason of science) could not overcome the impasse between agroecology and biotechnology. Urs Niggli, a Swiss Agronomist, attempted to defend organic farming while proposing a win–win in ‘diversifying agroecological systems with smart farms and precision farms—and that is something [beneficial] for the big ones’.Footnote 15 Ertharin Cousin, a distinguished fellow with The Chicago Council on Global Affairs, inserted science’s peacemaking role into the wider ambit of politics: ‘Achieving the food system is a complex…it’s almost as complicated as democracy. But we make democracy work. We can make collaborative action across these diverse groups work’.Footnote 16

In sum, the Scientific Group courted diverse audiences, worked to organize consensus for its proposals, and presented itself as an arbiter of sound (and peaceable) judgement. In so doing, it cast critics of the 4IR agenda as not only unmoored from a growing scientific consensus (however self-produced that consensus might be) but also anti-democratic and antagonistic to the inclusive politics the UNFSS purports to cultivate. Here, it was noteworthy that Cousin was not just anyone.Footnote 17 A powerful Black woman lawyer, she and others were there to move the needle on broader orientation emerging across the UNFSS: the rise of ‘inclusive’ STI.

‘Woke Science’

Anyone prepared for white men in suits at Science Days and the Pre-summit would not have been disappointed. But these events also revealed to anyone paying attention that representational dynamics had shifted. From Black and Brown women occupying key positions of powerFootnote 18 to sessions explicitly entitled ‘Achieving more inclusive food systems’, the berth for recognition (identity and identification); representation (democracy, community, belonging); and even redistribution (concerns with class, social difference, and inequality) had clearly shifted. In one day alone at Science Days, sessions appealed to Youth (‘how to effectively and appropriately engage, include, incentivize, and empower youth in science and innovation for food systems transformations’), to Indigenous People (‘how to effectively and appropriately support and use traditional and indigenous peoples’ knowledge’), and to Women ‘strengthening rights, and how to effectively and appropriately engage, include, and empower women in science and innovation for food systems transformation.Footnote 19

Volumes could be written about the shortcomings of these strategies, including the difference between words and practice, the murkiness of ‘support and use’ Indigenous knowledge, and more. For our purposes, we point to just two core issues. First is about politics of representation. UNFSS organizers spent months recruiting youth, Indigenous people, women, and other ‘diverse’ participants in an attempt to appear inclusive and benefit from the legitimation that BIPOC and other marginalized communities would bring to the process. Eventually, they also billed the UNFSS as a ‘People’s Summit’. This practice perpetuated a longstanding colonial tradition that Indigenous peoples know well: a few amenable tribal members are enrolled and enabled to speak for a larger community that has neither consented nor often been engaged at all. The UNFSS case is particularly remarkable because the Civil Society and Indigenous Peoples Mechanism—representing more than 600 million peasant and Indigenous farmers and workers—was actively protesting against the Summit and disavowing its legitimacy.Footnote 20

Such politics of representation are hardly lost on social movements. On Democracy Now, Million Belay, general coordinator of the Alliance for Food Sovereignty in Africa (AFSA), spoke to the issue of Dr. Kalibata’s role in the Summit, pivoting attention from the individual to the institutional:

Maybe they have selected her because she’s a woman, she’s a Black woman, she’s an African woman, as a form of representing this as a global agenda. Maybe, in terms of image, she fits that bill. But the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa has 13 board members. Eight of them are from outside Africa. And [AGRA] is registered in the U.S. The Rockefeller Foundation, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and some companies are on the board of AGRA. So this is an outside-controlled institution. This shows that the corporate world wanted to control this event.Footnote 21

The second, related, shortcoming of UNFSS inclusivity was the structural failures it obscures. In the US context, Nancy Fraser’s ‘progressive neoliberalism’ describes an alliance of mainstream currents of new social movements (feminism, anti-racism, multiculturalism, and LGBTQ rights), on the one side, and high-end ‘symbolic’ and service-based business sectors (Wall Street, Silicon Valley), on the other. In this alliance, she suggests, the former unwittingly lend their charisma to the latter and ‘ideals like diversity and empowerment, which could in principle serve different ends, now gloss policies that have devastated manufacturing and what were once middle-class lives’ (Fraser 2017). This is how it came to be that the US buzzed with talk of ‘diversity’, ‘empowerment’, and ‘non-discrimination’ even while its manufacturing cratered in the post-NAFTA years. In the context of the UNFSS, international women’s rights movements, a global racial reckoning, and hard-won Indigenous and Peasants recognitions in international lawFootnote 22 have similarly become fodder for liberal capture and multi-stakeholder inclusivity. Unsurprisingly, in the long shadow of COVID-19 and the climate crisis, the UNFSS was abuzz with inclusivity at every turn.

The results on the UNFSS stage were straight from Fraser’s playbook. Identifying progress (here ‘sustainable development’) with meritocracy instead of equality, inclusivity at the Summit was equated with the rise of a small elite of ‘champions’, of women, minorities, Indigenous people, and youth. The goal remained a winner-take-all corporate mentality instead of the smashing of hierarchies altogether. What is arguably different now is that science, technology, and innovation have become the handmaidens of this pursuit. Previously satisfied to protect entangled epistemic tracks of white science and Green Revolutions (Eddens 2019), dominant scientific actors appear self-aware of whiteness, patriarchy, and privilege. Awkwardly, as the UNFSS illustrates, they are carving out a woke science—‘to put all the people together’—and moreover, to emulate social movement scripts (Fig. 3). But as progressive neoliberals do, the UNFSS studiously avoided baseline forces of systemic inequality. Ignoring uneven political-economic power, ecological debt, and the hierarchies of knowledge and being that colonial-modernity assumes, its woke science nudges a few lucky ‘diverse’ spokespersons up the ladder of meritocracy while propping up the status quo atop a mountain of ‘neutral’ scientific evidence. As executive director of Focus on the Global South, Shalmali Guttal, told us: ‘I would like to see the Science Group’s innovations to address rights to land and territory, debt, suicides, distress migration….’

‘In Defense of Black Life—Demands Rooted in Systemic Change’. Compare the style of this artwork with Fig. 2. (credit: @radicalroadmaps)

In sum, while the Scientific Group has reinforced certain boundaries around science, it has eroded other boundaries that typically define ‘science’ and who participates in its making. The fact that woke science collapses under the weight of its own contradictions has not, however, prevented further counter-boundary work at the heart of a fourth-industrial vision.

Innovations for Everyone and Anything

In August, the Scientific Group released the final version of its strategic report on opportunities for science and technology to achieve the UNFSS goals, and identified seven science-based innovation areas that ‘must’ be pursued for a successful transformation (von Braun et al. 2021b). This report bristled with signs of counter-boundary work in speaking to a wider berth of S&T makers, including start-up businesses, pro-poor non-profit organizations, Indigenous communities, and more. However, the seven innovations at the heart of the report are a curious melange: of solutions to fix challenges like ending hunger, of measures to ‘de-risk’ food systems, of ways to open new frontiers for production such as the oceans. In highlighting these and other innovation areas, the Scientific Group repeatedly throws contradictory aims and solutions together: for example, digital technologies like blockchains can assure both efficient production and empowerment of women, youth, smallholders, and Native peoples. Yet the report never once recognizes the agency and endogenous capacities of these communities to make technologies they want and need. Instead, engineering and digital innovations are taken, a priori, as ‘empowering’—regardless of empirical conditions or histories that would strongly suggest otherwise potentials (Patel 2013). Another common thread is that innovations portrayed as enabling sustainability frequently increase resource use and extraction, even if the sources (and fallout) are ‘elsewhere’ and obscured (Ajl 2021).

What is most striking, however, is the internal incoherence of these proposals for innovation. Digital technologies, AI, and biotech stand adjacent to statements about preventing corporate monopolies. Injunctions to protect smallholder livelihoods share the page with calls to lift barriers to free and open trade. More accurate weather forecasting suggests a low-tech way to support smallholders and farmworkers while digital monitoring and robotics point to an likelihood of surveilling and displacing both. Innovations are always equated with ‘solutions’ and neither have limits in a hyperbolic space where science is hitched to innovations and innovations spill over into scientific, economic, and policy spheres. Green Revolution science was always about conjoining S&T, capital, and geopolitical power, but the scientists mostly kept to their corner. The Scientific Group here extended its authority well past those boundaries into governance realms it doesn’t know much about—while it continues to erect boundaries against those who do.

Conclusions

Few people know if the UNFSS will become an event that marks a critical inflection point in sustainable development, or if a year from now, people will hardly remember it occurred. What is increasingly clear is that the parameters of science, technology, and innovation are shifting in ways that should provoke our sustained attention. As Green Revolution strategies show mounting evidence of their failures to nourish people and safeguard the environment, old industrial STI is losing legitimacy at the pace of melting glaciers, growing food pantry lines, and biodiversity loss. Agroecology’s synergies of ecological science, traditional knowledge, and anti-colonial restructuring offer a ready way to address these world-ecological challenges—but not without a fatal blow to the status quo. The UN-WEF partnership and the UN Food Systems Summit it birthed thus represent an effort to hang onto material power and epistemic legitimacy, especially as social movements comprising peasants, Indigenous communities, scholar-activists, workers, and educators of all types increasingly welcome an agroecological transition. Inclusivity, diversity, and empowerment have ironically been the badge of an elite Global reset community, where spokespersons are people of color and shareholders are the billionaire class. But where inclusivity rests on ‘stakes’ rather than ‘rights’, nobody appears accountable for securing the latter, even while proliferating audiences can populate the former. As we have argued in this article, science has been central to achieving credibility for this multi-stakeholder approach. The Fourth Industrial Revolution has dropped old Green Revolution STI into sustainable packaging and sealed up the unglued corners with appeals to more participatory knowledge-making, consensus building, and ways to seem woke.

Will it work? On the day of the UNFSS, 23 September 2021, we could see two possible paths unfolding. At the Global People’s Kitchen Counter-Summit, organized by the CSM North America, Denisa Livingston, a Diné woman and an Appointed Member of the Champions Network of the UNFSS, explained why she was there instead of at the formal Summit:

Our seeds and traditional foods need to be protected not just for now, but also for the future generations, protecting the heritage and the history. Protecting those indigenous seed varieties and also our sacred food. This is a way for us to exercise our inherent sovereignty.… As we think about us as Indigenous people transforming the world food system, we need to think about how we have been negatively impacted by it. [We do so] by sharing our narratives, knowing that we have to put lived experiences as expertise at the forefront.Footnote 23

At the official Summit, the opening panel was in fine form, featuring a Miskita Indigenous feminist, an African youth advocate, and a women’s rights organizer (Fig. 4). ‘Today we come to tell you that Indigenous food systems truly are game changers’, said Dr. Myrna Kay Cunningham Kain. Ms. Reema Nanavaty described the power of cooperative labour organizing for self-employed Indian women.Footnote 24 One could be forgiven for temporarily mixing up the UN Food Systems Summit with the People’s Counter-Summit. As languages, discourses, and strategies meld, the confusion of inclusions is something to watch. Nomenclatures now meld: ‘The People’s Summit’ of UNFSS and ‘The Global People’s Summit’ of food sovereignty movements. The inclusive, participatory, and action-oriented nature of the Summit appears, on the surface, much like the prefigurative politics of agroecology (Méndez et al. 2013). La Vía Campesina and other movements sliced through this ruse with a scalpel, long before Summit proceedings were underway (LVC-NA 2021). In better understanding how STI helps dominant actors in global food policy continually rework their power and legitimacy, we hope to extend the strategies for reclaiming that terrain. Science, technology, and innovation do not belong to WEF, CGIAR, Gates, or even FAO; they can be taken up, reworked, imagined, and practiced otherwise.

Notes

Our study is based on documentary analysis and short-term participant observation of processes leading up to and through the September 2021 UN Food System Summit. We observed sessions during the Science Days and pre-Summit events in July 2021, reviewed archived video footage, and generated transcripts from notes for the rapid-response analysis this study represents. Summit Action Tracks and the Scientific Group both produced numerous documents which we reviewed, alongside a focused read of UNFSS website materials and Scientific Group memberships, networks, and activities.

http://www.fao.org/about/meetings/second-international-agroecology-symposium/about-the-symposium/en/. Accessed 24 September 2021.

In 2014, FAO Director General José Graziano da Silva closed the First International Agroecology Symposium by saying that the meeting had opened’a new window in the Cathedral of the Green Revolution’ that can help to achieve the Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development.

https://www.weforum.org/projects/circular-economy accessed 24 September 2021.

https://www.weforum.org/focus/the-great-reset accessed 24 September 2021.

https://www.weforum.org/press/2019/06/world-economic-forum-and-un-sign-strategic-partnership-framework/. accessed 24 September 2021.

https://summitdialogues.org/ accessed 24 September 2021.

https://www.gainhealth.org/partnerships accessed 24 September 2021.

https://eatforum.org/about/who-we-are/ accessed 24 September 2021.

https://sc-fss2021.org/about-us/bios-of-members/ accessed 24 September 2021.

https://sc-fss2021.org/events/sciencedays/sciencedays-about/ accessed 24 September.

Final Statement: Science and Innovations for a Sustainable Food System, Workshop of the Scientific Group for the UN Food Systems Summit and the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, Vatican City, April 21–22, 2021. http://www.pas.va/content/accademia/en/events/2021/foodsystems/final_statement.html accessed 24 September 2021.

https://www.professorzilberman.com/2017/10/07/monsanto-rip/ accessed 24 September 2021.

Session 4 ‘Why the Fight’: http://www.fao.org/webcast/home/en/item/5600/icode/ accessed 24 September 2021.

Session 4 ‘Why the Fight’: http://www.fao.org/webcast/home/en/item/5600/icode/ accessed 24 September 2021.

Cousin, a Black woman lawyer who served under President Barack Obama as the US Ambassador to the FAO, was in 2014 ranked number 45th on the Forbes Magazine’s List of The World’s 100 Most Powerful Women and was named to the TIME 100 most influential people in the world list. Her paean to democracy eclipses the militaristic geopolitics of the Chicago Council, with its close ties to NATO and to a deep network of philanthropy capital, corporations, and individuals invested in asserting US influence through foreign policy.

UNFSS Special Envoy Kalibata is from Rwanda, UN Deputy Secretary General Amina Mohammed is Nigerian, and Scientific Group co-chair Kaosar Afsana is Bangladeshi.

https://sc-fss2021.org/events/sciencedays/program/ accessed 24 September 2021.

https://www.democracynow.org/2021/9/23/un_food_summit_critics_corporate_agriculture accessed 24 September 2021.

Specifically, the UN Declaration on the Rights of Peasants and Other People Working in Rural Areas (UNDROP) and the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

https://facebook.com/events/s/peoples-kitchen-counter-mobili/380033806941611/ accessed 24 September 2021.

https://www.unfoodsystems.org/index.php accessed 24 September 2021.

References

Ajl, Max. 2021. A People’s Green New Deal. London: Pluto Press.

Anderson, Colin R., and Chris Maughan. 2021. ‘The Innovation Imperative’: The Struggle Over Agroecology in the International Food Policy Arena. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2021.619185.

Canfield, Matthew, Molly D. Anderson, and Philip McMichael. 2021. UN Food Systems Summit 2021: Dismantling Democracy and Resetting Corporate Control of Food Systems. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 5: 103. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2021.661552.

de Sowa, Ivan Sergio Freire., and Lawrence Busch. 1998. Networks and agricultural development: The case of soybean production and consumption in Brazil. Rural Sociology 63 (3): 349–371. https://doi.org/10.1111/ruso.1998.63.3.349.

Eddens, Aaron. 2019. White science and indigenous maize: The racial logics of the Green Revolution. The Journal of Peasant Studies 46: 653–673. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2017.1395857.

Escobar, Arturo. 2012 [1995]. Encountering Development: The Making and Unmaking of the Third World. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press.

Ezrahi, Yaron. 1990. The Descent of Icarus: Science and the transformation of contemporary democracy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Fairclough, Norman. 1993. Discourse and Social Change. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Fakhri, Michael. 2021. Interim report of the Special Rapporteur on the right to Food. UN Doc A/76/237. New York, NY: United Nations.

Fitzgerald, Deborah. 1986. Exporting American Agriculture: The Rockefeller Foundation in Mexico, 1943–53. Social Studies of Science 16 (3): 457–483. https://doi.org/10.1177/030631286016003003.

Fraser, Nancy. 2017. The End of Progressive Neoliberalism. Dissent Magazine, 2 January.

Fresco, Louise O. 2013. The GMO Stalemate in Europe. Science 339: 883–883. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1236010.

Funtowicz, Silvio O., and Jerome R. Ravetz. 1993. Science for the post-normal age’. Futures 25 (7): 739–755. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-3287(93)90022-L.

Giraldo, Omar Felipe, and Peter M. Rosset. 2018. Agroecology as a territory in dispute: Between institutionality and social movements. The Journal of Peasant Studies 45 (3): 545–564. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2017.1353496.

Gieryn, Thomas F. 1999. Cultural boundaries of science: Credibility on the line. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Gleckman, Harris. 2016. Multi-stakeholderism: A Corporate Push for a New Form of Global governAnce. The Transnational Institute. https://www.tni.org/en/publication/multi-stakeholderism-a-corporate-push-for-a-new-form-of-global-governance.

Hajer, Maarten A. 1995. The Politics of Environmental Discourse: Ecological Modernization and the Policy Process. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

HLPE. 2018. Multistakeholder Partnerships to Finance and Improve Food Security and Nutrition in the Framework of the 2030 Agenda. A report by the High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security, Rome. http://www.fao.org/publications/card/fr/c/CA0156EN/.

Hilgartner, Stephen. 2000. Science on Stage: Expert Advice as Public Drama. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

Iles, Alastair, Garrett Graddy-Lovelace, Maywa Montenegro, and Ryan Galt. 2017. Agricultural Systems: Co-Producing Knowledge and Food. In The Handbook of Science and Technology Studies, 4th ed., ed. U. Felt, R. Fouché, C. Miller, and L. Smith-Doerr. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

IPES-Food. 2020. One CGIAR with Two Tiers of Influence? http://www.ipes-food.org/pages/OneGGIAR.

Jasanoff, Sheila, ed. 2004. States of knowledge: The co-production of science and the social order. New York, NY: Routledge.

Jennings, B.H. 1988. Foundations of International Agricultural Research: Science and Politics in Mexican Agriculture. Boulder: Westview Press.

Latour, Bruno, and Steve Woolgar. 1979. Laboratory life. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Latour, Bruno. 1993. The Pasteurization of France. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Loconto, Allison Marie, and Eve Fouilleux. 2019. Defining Agroecology: Exploring the Circulation of Knowledge in FAO’s Global Dialogue’. The International Journal of Sociology of Agriculture and Food 25 (2): 116–137. https://doi.org/10.48416/ijsaf.v25i2.27.

LVC-NA (La Vía Campesina North America). 2021. Guterres Gives UN Food Summit to Bill Gates and Davos. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hAlr8KSq7qY.

McMichael, Philip. 2008. Development and Social Change: A Global Perspective. 4th ed. Sociology for a New Century Series. Los Angeles: Pine Forge Press.

Montenegro de Wit, Maywa, and Alastair Iles. 2016. Toward Thick Legitimacy: Creating a Web of Legitimacy for Agroecology. Elementa: Science of the Anthropocene. https://doi.org/10.12952/journal.elementa.000115.

Méndez, Ernesto V., Christopher M. Bacon, and Roseann Cohen. 2013. Agroecology as a Transdisciplinary, Participatory, and Action-Oriented Approach. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems 37: 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/10440046.2012.736926.

Nyéléni. 2015. Declaration of the International Forum for Agroecology, Nyéléni, Mali. Development 58: 163–168. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41301-016-0014-4.

Patel, Raj. 2013. The Long Green Revolution. The Journal of Peasant Studies 40 (1): 1–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2012.719224.

Perkins, John H. 1990. The Rockefeller Foundation and the green revolution, 1941–1956. Agriculture and Human Values 7 (3): 6–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01557305.

Pigman, Geoffrey. 2007. The World Economic Forum: A multi-stakeholder approach to global governance. London: Routledge.

Schwab, Klaus. 2017. The Fourth Industrial Revolution. New York, NY: Currency Books.

Science Days. 2021. Science Days: Implications for a Science Agenda for the United Nations Food Systems Summit 09–19 July 2021. Prepared by: Rajul Pandya-Lorch, Heike Baumüller, Sundus Saleemi, Preetmoninder Lidder. https://sc-fss2021.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Science-Days_Report.pdf.

SciGroup (Scientific Group). 2020. Terms of Reference. http://sc-fss2021.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Terms_of_Reference_web.pdf.

SciGroup (Scientific Group). 2021. Science and Innovations for Food System Transformations and Summit Actions. The Scientific Reader: Papers by the Scientific Group and its partners in support of the UN Food Systems Summit. https://sc-fss2021.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/ScGroup_Reader_UNFSS2021.pdf.

Shapin, Steven, and Simon Schaffer. 1985. Leviathan and the air-pump. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Shapin, Steven. 2009. The Scientific Life: A Moral History of a Late Modern Vocation. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

The Economist. 2006. The mystery of capital deepens. The Economist, 24 August.

von Braun, Joachim, Kaosar Afsana, Louise O. Fresco, Mohamed Hassan, Maximo Torero. 2021a. Food Systems—Definition, Concept and Application for the UN Food Systems Summit, UN Food Systems Summit Paper, March 6. https://doi.org/10.48565/scfss2021-re63.

von Braun, Joachim, Kaosar Afsana, Louise O. Fresco and Mohamed Hassan. 2021b. Science for Transformation of Food Systems: Opportunities for the UN Food Systems Summit, UN Food Systems Summit Paper, revised August 2. https://sc-fss2021.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Scientific-Group-Strategic-Paper-Science-for-Transformation-of-Food-Systems_August-2.pdf.

von Braun, Joachim, Kaosar Afsana, Louise O. Fresco, and Mohamed Hassan. 2021c. Food Systems: Seven Priorities to End Hunger and Protect the Planet. Nature 597: 28–30.

von Braun, Joachim, Kaosar Afsana, Louise O. Fresco, Mohamed Hassan. 2021d. Science and Knowledge for the UN Food Systems Summit 2021. https://sc-fss2021.org/2021/09/14/science-and-knowledge-for-the-un-food-systems-summit-2021/.

WEF (World Economic Forum). 2018. Innovation with a Purpose: The role of technology innovation in accelerating food systems transformation. https://www.weforum.org/reports/innovation-with-a-purpose-the-role-of-technology-innovation-in-accelerating-food-systems-transformation.

Wittman, Hannah, Annette A. Desmarais, and Nettie Wiebe. 2010. The Origins & Potential of Food Sovereignty. In Food Sovereignty: A New Rights Framework for Food and Nature?, ed. Hannah Wittman, Annette A. Desmarais, and Nettie Wiebe. Oakland: Food First Books.

Yapa, Lakshman. 1993. What are Improved Seeds? An epistemology of the Green Revolution. Economic Geography 69 (3): 254–273. https://doi.org/10.2307/143450.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The contribution is free from any conflicts of interest, including all financial and non-financial interests and relationships.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Montenegro de Wit, M., Iles, A. Woke Science and the 4th Industrial Revolution: Inside the Making of UNFSS Knowledge. Development 64, 199–211 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41301-021-00314-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41301-021-00314-z