Abstract

Chinese leadership has received growing research attention amid the rapid development of the Chinese economy, the rising influence of the Chinese government and companies in the global arena, and China’s business transformation and institutional reform. However, the extant literature has tended to adopt Western leadership theories and test them in the Chinese context. By reviewing Chinese leadership studies, this paper highlights the importance of context in shaping leadership attitudes, behaviors, activities, and their consequences. To further advance Chinese leadership research and its impact on management practice, we suggest that it is crucial to pay closer attention to the cultural micro-foundations underpinned by traditional Chinese philosophy. We offer six promising avenues for future research: (1) a nuanced and critical approach to the role of context, (2) the combination of Western and Chinese thoughts, (3) indigenous leadership theory development, (4) gender and leadership, (5) leadership and performance, and (6) leadership in crisis management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Leadership can play a critical role in business growth and economic recovery (Ashford & Sitkin, 2019; Sarabi et al., 2020)), especially in this age of uncertainty, risk, disruption, and societal grand challenges facing the world and global economy (Liu & Froese, 2020). Chinese leadership is an important research area that underpins economic growth, business development, global engagement, and institutional transformation in China (Zhang et al., 2014). In China, leadership research is among the most popular research areas in organizational behavior and management. Similarly, Chinese leadership research is a major stream in submissions to and publications in Asian Business & Management and other related scholarly journals (Froese et al., 2022). Considering these trends, Asian Business & Management features a focused issue on Chinese leadership in 2023. This perspective paper serves as the lead article of this focused issue by providing a holistic picture of Chinese leadership research, offering a nuanced overview of this topic, and suggesting future research directions. We tackle the following research questions: What research on Chinese leadership has been conducted, and how and why has it been conducted? What are the future research directions?

We first provide a brief overview of leadership theories developed in Western contexts (e.g., Fischer & Sitkin, 2023; Yammarino et al., 2005) and discuss the ways in which they have been adopted in the Chinese context. We accentuate the role of context in shaping and influencing Chinese leadership research (Child, 2009; Whetten, 2009), especially in public–private, entrepreneurial, and global contexts. By reviewing several exemplary studies, we highlight the important contribution of cultural and philosophical micro-foundations to Chinese leadership research that has been receiving increasing scholarly attention. We illuminate several future research directions for scholarly inquiry related to Chinese leadership: (1) a nuanced and critical approach to understanding the role of context, (2) the combination of Western and Chinese thoughts, (3) indigenous leadership theory development, (4) gender and leadership, (5) leadership and performance, and (6) leadership in crisis management.

Literature review

A brief review of leadership theories and their adaptation to the Chinese context

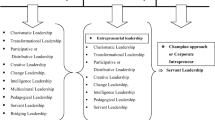

As a vibrant academic field with a long history, leadership research has assembled a broad spectrum of theories in understanding, predicting, and intervening in leaders’ behaviors and activities. Leadership research focusing on leader traits, styles, and behaviors has been dominant (Fischer & Sitkin, 2023; Yammarino et al., 2005). For instance, the rich set of theoretical frameworks in this domain includes transactional and transformational leadership (Kuhnert & Lewis, 1987; Van Knippenberg & Sitkin, 2013). The distinction between these leadership styles relies on leaders’ inclination to focus on “getting things done,” similar to a transaction, or promoting a transformational nature to cultivate employees with a positive impact on organizations. Charismatic leadership emphasizes leaders’ charisma or unique qualities, which can explicitly or implicitly influence others’ behaviors. Similarly, the research stream on narcissistic CEOs pays close attention to the unique traits of such leaders, such as dominance, self-confidence, a sense of entitlement, grandiosity, and low empathy, and their impact on organizational strategy and performance (Chatterjee & Hambrick, 2007). Increasingly, the notion of moral leadership (Fehr et al., 2015) connects leadership to ethics, responsibility, and sustainable development for individuals, organizations, and society at large. Ultimately, leadership is about influence, and the true power of influence stems from authenticity and consistency (DeRue et al., 2011). The vast range of leadership theories is therefore conducive to capturing the multifaceted phenomenon of leadership.

Research further revealed that leadership behavior and effectiveness differ substantially across countries (Hong et al., 2016; Yammarino et al., 2005). However, existing leadership theories are mainly developed based on the observation of business and management practices in Western contexts. Chinese leadership research has largely been dominated by a preoccupation with applying these theories in the Chinese context (Zhang et al., 2014). This approach subscribes to the perspective of appreciating the role of context in shaping theory (Johns, 2006) and the interplay between context and theory in Chinese management research (Child, 2009; Whetten, 2009). For instance, using leader–member exchange (LMX) theory, one study examined the influence of moral leadership on employee creativity in the Chinese context (Gu et al., 2015). Another study investigated inclusive leadership and team creativity (Jia et al., 2021). Regarding charismatic leadership theory, research has examined the mediating role of loyalty to one’s supervisor in applying and extending the charismatic leadership model in Chinese contexts (Wu & Wang, 2012). Trust and organizational control are pivotal in leadership research (Long & Sitkin, 2018). In times of disruption and during the aftermath of the global health crisis of COVID-19 (Liu et al., 2020), restoring and building trust is critical for leadership in both Asia and the rest of the world.

In line with the suggestion regarding leadership research in Asia (Liden, 2012), we argue that Chinese leadership research followed a similar trajectory in adapting Western theories in its early stages, which helped translate and transfer Western theories to a new context. This helped advance existing theories by redefining boundary conditions, relaxing assumptions, and/or incorporating contextual factors. For instance, the research stream on paternalistic leadership has incorporated some contextual variables, such as trust (Chen et al., 2014), or explored the utility of this theoretical perspective from a comparative convergence-versus-divergence lens (Aycan et al., 2013). In addition, Confucian and Taoist (also known as Daoist) values are important contextual factors that can influence transformational leadership in the Chinese context (Lin et al., 2013). Similar to observations on ethical leadership (Wang et al., 2017), one definition or concept of leadership may have multiple manifestations in different contexts. Therefore, construct clarity (Suddaby, 2010) should play an important role in advancing leadership research by clearly defining the boundary conditions of the focal concept.

The role of context in shaping Chinese leadership

The scholarly debate on whether theory should be context free or context dependent has been an enduring topic without conclusive recommendations (Whetten, 2009). In the arena of Chinese management and business studies, context plays an important role in helping scholars obtain a nuanced understanding of business phenomena and management practices (Meyer, 2015). For example, Chinese globalization research needs to appreciate the role of context in understanding the differences between home and host countries across multiple dimensions—culturally, institutionally, politically, and socially (Child, 2009). Essentially, emerging economies—China included—are fast moving, with a high degree of dynamism and change; thus, a dynamic perspective must also be embraced in understanding contexts and incorporating them into the research agenda.

Regarding Chinese leadership research, despite studies that advocate for the universality of leadership theories and constructs (e.g., Schuh et al., 2021), we demarcate some salient contexts and highlight the extent to which they can shape leadership research in China. First, state-owned enterprises (SOEs) are an important type of business organization in China. Although SOEs exist around the world, with important implications for business and society (Bruton et al., 2015), their significant influence in China is regarded as one of the key characteristics of the Chinese economy. Thus, understanding SOEs’ leadership behaviors and practices may generate revealing insights into how to advance both scholarly inquiry and management practices. Chinese SOEs are owned by the state and managed by a governmental agency, the State-Owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC) (Wang et al., 2012). The top leaders of SOEs are appointed by the government through the Department of Organization. The performance of SOEs determines their professional career trajectories. SOEs must often consider both profit-driven goals and socially responsible goals. For example, some research has evidenced this important dimension, while corporate social responsibility (CSR) reporting tends to carry more substance in SOEs in comparison to privately owned enterprises in China (Marquis & Qian, 2014). Regarding leadership research, leaders are instrumental in driving and cultivating organizational culture. The distinctive nature of SOEs’ organizational culture may positively affect business performance and management practices in various interorganizational settings. For instance, in the context of Chinese domestic mergers and acquisitions (M&A), leaders’ identity work strongly influences the sociocultural integration process in the post-M&A stage; thus, privately owned acquirers can benefit from learning about the culture of SOEs to become more caring organizations (Xing & Liu, 2016).

Another salient context for understanding Chinese leadership is entrepreneurship and innovation, especially from the indigenous lens (Bruton et al., 2018; Franzke et al., 2022). Entrepreneurship has been a key driver of the Chinese economy through the transformation of the country’s business environment and institutional infrastructure (Nee et al., 2018). From the Red Hat strategy (Chen, 2007) to the legitimatization of private enterprise status (Eesley, 2016), entrepreneurial leadership involves a multitude of stakeholders, global and local interactions, and regional development beyond geographical boundaries (Liu, 2020). Entrepreneurial leadership (Leitch et al., 2013) in China demonstrates its own characteristics, notably through the returnee entrepreneurship phenomenon. For instance, returnees’ human and social capital may provide comparative advantages in mobilizing international resources (Liu, 2017). As a collective endeavor and never a solo journey, entrepreneurship requires collaboration, an open mindset, and a wide range of partnerships. Successful entrepreneurial leaders are skilled at working with government and local enterprises (Xing et al., 2018), allowing them to accumulate location-sensitive institutional capital. Furthermore, entrepreneurial leadership is instrumental in fostering a healthy entrepreneurship and innovation ecosystem through dynamic interactions and collaborations among universities, governments, and industries (Liu & Huang, 2018). From a relational perspective, an entrepreneurial leader determines team dynamism by providing strategic responses to a fast-changing business environment in an increasingly volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous world (Xing et al., 2020a, 2020b).

Furthermore, the dynamics of globalization provide an important context for understanding Chinese leadership. From attracting foreign direct investment to China (Froese et al., 2019) through international partnerships (Collinson & Liu, 2019) to the more recent trend of Chinese companies going global, leaders’ decision-making has influenced the shape and weight of Chinese companies’ global strategy and manifestations. When entering advanced economies, Chinese companies tend to utilize M&As as the preferred mode of entry. Importantly, light-touch integration, i.e. minimal integration, provides flexibility for leaders to exercise organizational control to benefit from both the exploration and exploitation of the knowledge base (Zhang et al., 2020). With regard to Chinese leadership practices in less-developed countries, the cultural proximity of Chinese Confucian culture and African Indigenous Ubuntu culture paves the way for the emergence of crossvergent human resource management (HRM) practices in managing African employees of Chinese firms in Africa (Xing et al., 2016). Notably, the influence of family culture becomes more dominant in the context of SOEs, benefiting African employees’ attitudes toward work and work commitment. Arguably, in the age of US–China rivalry, corporate diplomacy has become increasingly important for navigating the new geopolitical world order (Li et al., 2022). However, leaders with a vision and the ability to drive communication and collaboration between China and the rest of the world are at the center of this business strategy. Therefore, it is not only Chinese business leaders’ willingness per se but also their ability to act as boundary spanners (Liu & Meyer, 2020) that can determine globalization and international cooperation moving forward.

Cultural and philosophical micro-foundations and Chinese leadership research

Given the prevailing influence of context and contextual factors that shape Chinese leadership behavior, practice, and activity, one nascent yet important context—the cultural and philosophical context—remains less understood than the blossoming field of Chinese leadership research. The emergence of Chinese leadership literature that adopts a cultural and philosophical perspective, echoing the micro-foundational movement in management studies (Barney & Felin, 2013), has begun to fill this important gap (Ma & Tsui, 2015; Xing et al., 2020a, 2020b). The micro level, including processes, antecedents, and mechanisms, can be conducive to explaining macro-level organizational observations and management practices (Liu et al., 2017). A nuanced understanding of micro-foundations can significantly advance research in international business (Liu et al., 2019), strategy (Teece, 2007), management practice (Foss, 2011), and organizational performance (Eisenhardt et al., 2010; Lewin et al., 2011). Thus, cultural and philosophical micro-foundations may provide both novel perspectives and revealing insights to understand organization and management theory, with important implications for business practice.

In essence, by leveraging the power of historical and traditional cultural resources, this indigenous approach toward leadership research from a cultural and philosophical perspective is rooted in the long-lasting theory of “culture as resources” (Weber & Dacin, 2011). For example, by referring to the Taoist philosophy of wu wei, Chinese leaders may exhibit distinctive indigenous leadership practices, such as flow, self-protection, and excuse (Xing & Sims, 2012). By examining the joint influences of Confucian and legalist philosophies, employees may become loyal to both individual leaders and their organizations in the pursuit of career progress in the context of supervisor–subordinate relationships (Xing et al., 2020a, 2020b). This example provides a more holistic and nuanced understanding of Chinese traditional culture, while the mainstream literature on culture’s impact on Chinese leadership tends to emphasize Confucian influences (Zhu & Warner, 2019), thus overshadowing other cultural resources. Furthermore, by exploring the underlying connection between Taoist philosophy and sustainability management, one study revealed that Taoist leadership may influence employee pro-environmental behaviors, especially voluntary ones (Xing & Starik, 2017).

Amid the emergence of paradox theory (Schad et al., 2016) and its rising importance in organization and management theory, its application in leadership research has given rise to the notion of paradoxical leadership. This seemingly contradictory leadership practice necessitates cultural and philosophical micro-foundations to explain observations and involves not only leaders themselves but also followership behaviors (Jia et al., 2018). Some recent work has examined the impact of paradoxical leadership on employee creativity (Zhang et al., 2022a, 2022b) and innovation in work teams (Zhang et al., 2021). This research stream has also joined the scholarly quest to encourage a “West-meets-East” approach to advancing concepts, theory, and management practice (Barkema et al., 2015). Thus, recent scholarly work lends further support to our belief that cultural and philosophical micro-foundations can make important contributions to Chinese leadership research.

Discussion

Prior research has provided important insights into Chinese leadership. At the same time, our literature review revealed that most prior research has paid scant attention to the unique Chinese context. To move the field forward, we provide suggestions for future research in the following section.

Future research directions

By building on and extending prior research and opening up completely new research directions, we provide suggestions for six areas of study that can help advance Chinese leadership research and business studies in general: (1) a nuanced and critical approach to understanding the role of context, (2) the combination of Western and Chinese thoughts, (3) indigenous leadership theory development, (4) gender and leadership, (5) leadership and performance, and (6) leadership in crisis management (see Table 1).

First, context is paramount. Building on the contingency perspective of leadership research (Yammarino et al., 2005), we advocate that future Chinese leadership research consider context. We encourage scholars to take a more nuanced and critical approach to context, especially in the Asian context. As discussed in this paper, besides the institutional, cultural, political, and social contexts widely used in international business research (Liu & Vrontis, 2017), context can include multiple dimensions across various organizational settings (e.g., public, state, entrepreneurial, team, and global settings). To advance Chinese leadership and Asian business and management research in general, it is important to pay closer attention to Asian contexts (Froese et al., 2020). Despite the general tendency to categorize Asia as the “Eastern context” in the “West-meets-East” narrative (Barkema et al., 2015), Asian contexts bear a nuanced degree of heterogeneity. Furthermore, leadership research can be significantly advanced by considering occupational contexts. However, scholars are urged to be cautious when using context with a critical lens. The misuse or abuse of context (Bruton et al., 2021) may not contribute to theoretical development and may have unintended consequences regarding the discounting or even distortion of construct clarity.

Second, the synergistic benefits stemming from the theoretical dialogue between existing Western theories and Chinese cultural and philosophical resources can help advance theories. Some earlier work has showcased the similarity between contemporary leadership theory and ancient Chinese theories of control (Rindova & Starbuck, 1997). In a similar vein, Professor James G. March’s wisdom and thoughts on organization and management share many commonalities with classic Chinese thinkers rooted in traditional Chinese culture and philosophy (Rhee, 2010). Several of the studies reviewed in this paper also demonstrated such a dialogical approach. Ambidexterity theory in leadership practice can be advanced by using Confucian and legalist philosophy as cultural and philosophical micro-foundations (Xing et al., 2020a, 2020b). Taoist wu wei (i.e., qualified inaction) can help advance the theory of self-reflexivity in Chinese leadership practice (Xing & Sims, 2012). The attributions of Taoist philosophy may also serve as cultural and philosophical micro-foundations of sustainability theory to advance our understanding of leaders’ influence on employee pro-environmental behaviors (Xing & Starik, 2017). However, this novel approach necessitates both the willingness and courage of scholars to explore a less-trodden path. Admittedly, this path cannot guarantee that a fruitful outcome will be achieved speedily, but it can promise interesting and fresh perspectives for examining and understanding leadership throughout the process.

Third, developing indigenous leadership theory is a strategically important undertaking for the scholarly community, especially for Chinese and Asian scholars. Alongside the shift in economic gravity from the West to the East, Asia may provide a unique opportunity to develop indigenous leadership theory. Leadership research relies on mutual learning and knowledge exchange between theory and practice (Ashford & Sitkin, 2019). China’s rapid economic development and vibrant business development, along with the rising influence of Chinese companies, can provide a setting in which to further develop, test, and experiment with indigenous leadership theory. Furthermore, addressing global grand challenges to achieve the United Nations’ 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is part of the quest for responsible and sustainable leadership practices. For instance, sensemaking with institutions elucidates how Chinese leaders may turn to institutional resources for the attainment of sustainable development (Wang et al., 2022). In light of Professor James G. March’s logic of appropriateness theory, one study endeavored to examine the unique characteristics of Chinese leadership and develop indigenous leadership theory by investigating the poetry (Xing & Liu, 2015) used by contemporary Chinese business leaders. To conclude, the development of indigenous leadership theory requires theoretical sensitivity, an in-depth understanding of leadership practice, and an appreciation of context, especially regarding cultural and philosophical micro-foundations.

Fourth, the extant research on Chinese leadership in the management literature has largely been gender neutral or has treated gender as a control variable. While a number of studies on female leaders (e.g., female board directors, females in top-management teams, or female managers) have begun to emerge, they have mainly tested the effect of gender on firm behaviors and firm performance, both financially and socially (e.g., Wu et al., 2021). Limited scholarly attention has been paid to the intersectionality of gender and culture regarding leadership philosophy, style, and behaviors. For example, while paternalistic leadership in the Chinese context has attracted considerable attention, gender has rarely been mentioned in this body of research (Peus et al., 2015; Sposato & Rumens, 2018). Here, Western feminist discourse may not be sufficiently applicable to the Chinese setting due to different gender ideologies, institutional support, and cultural expectations (Cooke, 2022; Sposato & Rumens, 2018). Future research may engage in an international comparison of gender and leadership in domestic and international firms to explore how and why Chinese female leaders may differ from or share similar leadership features with their counterparts in other societal contexts. As Sposato and Rumens (2018, p. 1201) argue, indigenous feminism is beneficial for international HRM scholars “because many are centrally concerned with unearthing localized Chinese understandings of gender and gender in/equality.”

Fifth, the extant research on leadership and performance has assumed a positive relationship between good leadership and good performance, such as employees’ creativity, innovativeness, organizational citizenship behavior, engagement, and commitment (e.g., Zhang et al., 2022a, 2022b). In the Chinese context, however, employees may still deliver high levels of performance when subjected to poor leadership styles or abusive leadership behaviors for economic, cultural, organizational, and individual reasons. For instance, the “996 phenomenon” (working from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m. 6 days a week) is widely used as a form of work intensification, often imposed by management through the use of control and culture (Wang, 2020). The combined effects of these factors may lead to individuals’ poor mental well-being in the long term. From an HRM perspective, future research could examine these issues to identify the boundary conditions for high performance under poor leadership and its long-term effects. It could also investigate the negative impact of HRM practices on leaders, as these effects may have a negative impact on their behaviors and thus be detrimental to their subordinates (e.g., Xi et al., 2021). Likewise, “good leadership” may not yield the desired employee behaviors and performance as expected. What might the reasons for this be, how can this be changed, what is HRM’s role in this, and what does this mean for leadership theorization? Future research could explore these issues further. Future research should also investigate how employees may rise up against abusive leadership to change leaders’ behaviors. Such actions depart considerably from the traditional Chinese culture of paternalism and obedience. Research in this direction will broaden the lens of leadership research in the Chinese context, which has largely been conducted from a top-down perspective, with employees at the receiving end. The study by Babalola et al., (2022, p. 386) serves as an enlightening example by investigating “when and why group ethical voice inhibits group abusive supervision.” They found that “group ethical voice reduces group abusive supervision, controlling for general group voice and group performance” and that “in powerful and socially proximal groups, group ethical voice reduces abusive supervision by fostering greater reflective moral attentiveness in group leaders” (Babalola et al., 2022, p. 386).

Sixth, the global COVID-19 pandemic has led to a surge of research on how to manage organizations and HRM in crisis contexts to help employees and organizations sustain their impact (e.g., Li et al., 2022; Liu & Froese, 2020). The role of leadership in crisis management may differ due to not only individual and organizational factors but also national responses informed by regulatory constraints, institutional arrangements, and cultural expectations. Li et al., (2022, p. 55) found that exposure to COVID-19 stimuli is “positively associated with conservation values emphasizing selfrestraint, submission, protection of order, and harmony in relations, which in turn influences workers’ willingness to tolerate mistreatment by authorities (i.e., abusive supervision, authoritarian leadership, exploitation).” China’s response to COVID-19 was markedly different from that of the rest of the world, and this had significant implications for organizational leaders in terms of their level of responsibilities and choices regarding initiatives. For example, in Australia, organizations shut down and employees worked from home during lockdown periods. Individuals were not permitted to enter work premises without authorization. Organizational leaders’ primary concern was compliance with government regulations and legal requirements. For those in essential businesses that had to remain operational, employees were allowed to go home after their shift and return to work as long as they tested negative. In contrast, in China, where critical businesses needed to remain operational, staff had to remain inside their company’s premises during work and sleep, without going home for weeks, to avoid contamination. Organizational leaders were expected to provide solutions to address their problems, such as giving each employee living materials, including quilts, sleeping bags, tents, moisture-proof pads, and toiletries. Organizational leaders also walked the floor each day to listen to problems and concerns and to provide solutions. Moreover, support was provided to the employees’ families to alleviate their hardships. For example, counseling and coaching were provided to employees and their families to mitigate their stress and anxiety and to demonstrate the companies’ approach to employee care. These interventions exemplify China’s pragmatic approach to solving problems and its paternalistic and collectivist culture. Based on the Western notion of HRM, this approach might be incomprehensible or unevenly unacceptable. However, these employee assistance/care practices are not unique to China, as similar examples can be found in other developing countries, such as Indonesia (Cooke et al., 2022). Future research on leadership in crisis contexts may explore how institutional conditions, cultural expectations, and national mentality in confronting crises can influence leadership accountabilities, expectations, skill requirements, and so on to elicit societal nuances.

Conclusion

Chinese leadership has received growing research attention amid the rapid development of the Chinese economy, the rising influence of the Chinese government and companies on the global arena, China’s recent business transformation and institutional reform. Our literature review highlights the importance of context in shaping leadership attitudes, behaviors, activities, and their impacts. Building on prior research, we proposed six promising future research directions: (1) a nuanced and critical approach to the role of context, (2) a combination of Western and Chinese thoughts, (3) indigenous leadership theory development, (4) gender and leadership, (5) leadership and performance, and (6) leadership in crisis management. We hope that our paper will inspire other researchers to conduct more research to further increase our understanding of Chinese leadership.

Data availability

There is no data generated from this research.

References

Ashford, S. J., & Sitkin, S. B. (2019). From problems to progress: A dialogue on prevailing issues in leadership research. The Leadership Quarterly, 30(4), 454–460.

Aycan, Z., Schyns, B., Sun, J.-M., Felfe, J., & Saher, N. (2013). Convergence and divergence of paternalistic leadership: A cross-cultural investigation of prototypes. Journal of International Business Studies, 44(9), 962–969.

Babalola, M. T., Garcia, P. R. J. M., Ren, S., Ogunfowora, B., & Gok, K. (2022). Stronger together: Understanding when and why group ethical voice inhibits group abusive supervision. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 43(3), 386–409.

Barkema, H. G., Chen, X.-P., George, G., Luo, Y., & Tsui, A. S. (2015). West meets East: New concepts and theories. Academy of Management Journal, 58(2), 460–479.

Barney, J., & Felin, T. (2013). What are microfoundations? The Academy of Management Perspectives, 27(2), 138–155.

Bruton, G. D., Peng, M. W., Ahlstrom, D., Stan, C., & Xu, K. (2015). State-owned enterprises around the world as hybrid organizations. The Academy of Management Perspectives, 29(1), 92–114.

Bruton, G. D., Zahra, S. A., & Cai, L. (2018). Examining entrepreneurship through indigenous lenses. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 42(3), 351–361.

Bruton, G. D., Zahra, S. A., Van de Ven, A., & Hitt, M. A. (2021). Indigenous theory uses, abuses, and future. Journal of Management Studies: https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12755

Chatterjee, A., & Hambrick, D. C. (2007). It’s all about me: Narcissistic chief executive officers and their effects on company strategy and performance. Administrative Science Quarterly, 52(3), 351–386.

Chen, W. (2007). Does the colour of the cat matter? The red hat strategy in China’s private enterprises. Management and Organization Review, 3(1), 55–80.

Chen, X.-P., Eberly, M. B., Chiang, T.-J., Farh, J.-L., & Cheng, B.-S. (2014). Affective trust in Chinese leaders: Linking paternalistic leadership to employee performance. Journal of Management, 40(3), 796–819.

Child, J. (2009). Context, comparison, and methodology in Chinese management research. Management and Organization Review, 5(1), 57–73.

Collinson, S., & Liu, Y. (2019). Recombination for innovation: Performance outcomes from international partnerships in China. R&D Management, 49(1), 46–63.

Cooke, F. L. (2022). Changing lens: Broadening the research agenda of women in management in China. Journal of Business Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-022-05105-1

Cooke, F. L., Dickmann, M., & Parry, E. (2022). Building sustainable societies through human-centred human resource management: Emerging issues and research opportunities. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 33(1), 1–15.

DeRue, D. S., Sitkin, S. B., & Podolny, J. M. (2011). From the guest editors: Teaching leadership—Issues and insights. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 10, 369–372.

Eesley, C. (2016). Institutional barriers to growth: Entrepreneurship, human capital and institutional change. Organization Science, 27(5), 1290–1306.

Eisenhardt, K. M., Furr, N. R., & Bingham, C. B. (2010). CROSSROADS—Microfoundations of performance: Balancing efficiency and flexibility in dynamic environments. Organization Science, 21(6), 1263–1273.

Fehr, R., Yam, K. C. S., & Dang, C. (2015). Moralized leadership: The construction and consequences of ethical leader perceptions. Academy of Management Review, 40(2), 182–209.

Fischer, T., & Sitkin, S. B. (2023). Leadership styles: A comprehensive assessment and way forward. Academy of Management Annals, 17(1), 331–372.

Foss, N. J. (2011). Invited editorial: Why micro-foundations for resource-based theory are needed and what they may look like. Journal of Management, 37(5), 1413–1428.

Franzke, S., Wu, J., Froese, F. J., & Chan, Z. X. (2022). Female entrepreneurship in Asia: Critical review and future directions. Asian Business & Management, 21, 343–370.

Froese, F. J., Malik, A., Kumar, S., & Sahoo, S. (2022). Asian business and management: A review and future research directions. Asian Business & Management., 21, 657–689.

Froese, F. J., Shen, J., Sekiguchi, T., & Davies, S. (2020). Liability of Asianness? Global talent management challenges of Chinese, Japanese, and Korean multinationals. Human Resource Management Review, 30(4), 100776.

Froese, F. J., Sutherland, D., Lee, J. Y., Liu, Y., & Pan, Y. (2019). Challenges for foreign companies in China: Implications for research and practice. Asian Business & Management, 18(4), 249–262.

Gu, Q., Tang, T.L.-P., & Jiang, W. (2015). Does moral leadership enhance employee creativity? Employee identification with leader and leader–member exchange (LMX) in the Chinese context. Journal of Business Ethics, 126(3), 513–529.

Hong, G., Cho, Y., Froese, F. J., & Shin, M. (2016). The effect of leadership styles, rank, and seniority on organizational commitment: A comparative study of U.S. and Korean employees. Cross-Cultural and Strategic Management, 23(2), 340–362.

Jia, J., Jiao, Y., & Han, H. (2021). Inclusive leadership and team creativity: A moderated mediation model of Chinese talent management. The International Journal of Human Resource Management. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2021.1966073

Jia, J., Yan, J., Cai, Y., & Liu, Y. (2018). Paradoxical leadership incongruence and Chinese individuals’ followership behaviors: Moderation effects of hierarchical culture and perceived strength of human resource management system. Asian Business & Management, 17(5), 313–338.

Johns, G. (2006). The essential impact of context on organizational behavior. Academy of Management Review, 31(2), 386–408.

Kuhnert, K. W., & Lewis, P. (1987). Transactional and transformational leadership: A constructive/developmental analysis. Academy of Management Review, 12(4), 648–657.

Leitch, C. M., McMullan, C., & Harrison, R. T. (2013). The development of entrepreneurial leadership: The role of human, social and institutional capital. British Journal of Management, 24(3), 347–366.

Lewin, A. Y., Massini, S., & Peeters, C. (2011). Microfoundations of internal and external absorptive capacity routines. Organization Science, 22(1), 81–98.

Li, J., Shapiro, D., Peng, M. W., & Ufimtseva, A. 2022. Corporate diplomacy in the age of US-China Rivalry. Academy of Management Perspectives.

Liden, R. C. (2012). Leadership research in Asia: A brief assessment and suggestions for the future. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 29(2), 205–212.

Lin, L.-H., Ho, Y.-L., & Lin, W.-H.E. (2013). Confucian and Taoist work values: An exploratory study of the Chinese transformational leadership behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 113(1), 91–103.

Liu, Y., & Huang, Q. (2018). University capability as a micro-foundation for the Triple Helix model: The case of China. Technovation, 76–77(August–September), 40–50.

Liu, Y., & Froese, F. J. (2020). Crisis management, global challenges, and sustainable development from an Asian perspective. Asian Business & Management, 19, 271–276.

Liu, Y. (2017). Born global firms’ growth and collaborative entry mode: The role of transnational entrepreneurs. International Marketing Review, 34(1), 46–67.

Liu, Y. (2020). The micro-foundations of global business incubation: Stakeholder engagement and strategic entrepreneurial partnerships. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 161, 120294.

Liu, Y., Collinson, S., Cooper, C., & Baglieri, D. (2022). International business, innovation and ambidexterity: A micro-foundational perspective. International Business Review, 31(3), 101852.

Liu, Y., Cooper, C. L., & Tarba, S. Y. (2019). Resilience, wellbeing and HRM: A multidisciplinary perspective. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 30(8), 1227–1238.

Liu, Y., Lee, J. M., & Lee, C. (2020). The challenges and opportunities of a global health crisis: The management and business implications of COVID-19 from an Asian perspective. Asian Business & Management, 19(3), 277–297.

Liu, Y., & Meyer, K. E. (2020). Boundary spanners, HRM practices, and reverse knowledge transfer: The case of Chinese cross-border acquisitions. Journal of World Business, 55(2), 100958.

Liu, Y., Sarala, R. M., Xing, Y., & Cooper, C. L. (2017). Human side of collaborative partnerships: A microfoundational perspective. Group & Organization Management, 42(2), 151–162.

Liu, Y., & Vrontis, D. (2017). Emerging markets firms venturing into advanced economies: The role of context. Thunderbird International Business Review, 59(3), 255–261.

Long, C. P., & Sitkin, S. B. (2018). Control-trust dynamics in organizations: Identifying shared perspectives and charting conceptual fault lines. Academy of Management Annals, 12(2), 725–751.

Ma, L., & Tsui, A. S. (2015). Traditional Chinese philosophies and contemporary leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 26(1), 13–24.

Marquis, C., & Qian, C. (2014). Corporate social responsibility reporting in China: Symbol or substance? Organization Science, 25(1), 127–148.

Meyer, K. E. (2015). Context in management research in emerging economies. Management and Organization Review, 11(3), 369–377.

Nee, V., Holm, H. J., & Opper, S. (2018). Learning to Trust: From relational exchange to generalized trust in China. Organization Science, 29(5), 969–986.

Peus, C., Braun, S., & Knipfer, K. (2015). On becoming a leader in Asia and America: Empirical evidence from women managers. Leadership Quarterly, 26, 55–67.

Rhee, M. (2010). The pursuit of shared wisdom in class: When classical Chinese thinkers meet James March. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 9(2), 258–279.

Rindova, V. P., & Starbuck, W. H. (1997). Ancient Chinese theories of control. Journal of Management Inquiry, 6(2), 144–159.

Sarabi, A., Froese, F. J., Chng, D. H. M., & Meyer, K. (2020). Entrepreneurial leadership and MNE subsidiary performance: The moderating role of subsidiary context. International Business Review, 29(3), 101672.

Schad, J., Lewis, M. W., Raisch, S., & Smith, W. K. (2016). Paradox research in management science: Looking back to move forward. The Academy of Management Annals, 10(1), 5–64.

Schuh, S. C., Cai, Y., Kaluza, A. J., Steffens, N. K., David, E. M., & Haslam, S. A. (2021). Do leaders condone unethical pro-organizational employee behaviors? The complex interplay between leader organizational identification and moral disengagement. Human Resource Management, 60(6), 969–989.

Sposato, M., & Rumens, N. (2018). Advancing international human resource management scholarship on paternalistic leadership and gender: The contribution of postcolonial feminism. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 32(6), 1201–1221.

Suddaby, R. (2010). Editor’s Comments: Construct clarity in theories of management and organization. Academy of Management Review, 35(3), 346–357.

Teece, D. J. (2007). Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strategic Management Ournal, 28(13), 1319–1350.

Van Knippenberg, D., & Sitkin, S. B. (2013). A critical assessment of charismatic—transformational leadership research: Back to the drawing board? Academy of Management Annals, 7(1), 1–60.

Wang, A.-C., Chiang, J.T.-J., Chou, W.-J., & Cheng, B.-S. (2017). One definition, different manifestations: Investigating ethical leadership in the Chinese context. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 34(3), 505–535.

Wang, J. J. (2020). How managers use culture and controls to impose a ‘996’ work regime in China that constitutes modern slavery. Accounting & Finance, 60(4), 4331–4359.

Wang, J., Guthrie, D., & Xiao, Z. (2012). The rise of SASAC: Asset management, ownership concentration, and firm performance in China’s capital markets. Management and Organization Review, 8(2), 253–281.

Wang, P., Xing, E. Y., Zhang, X., & Liu, Y. (2022). Sensemaking and sustainable development: Chinese overseas acquisitions and the globalisation of traditional Chinese medicine. Global Policy, 13, 23–33.

Weber, K., & Dacin, M. T. (2011). The cultural construction of organizational life: Introduction to the special issue. Organization Science, 22(2), 287–298.

Whetten, D. A. (2009). An examination of the interface between context and theory applied to the study of Chinese organizations. Management and Organization Review, 5(1), 29–55.

Wu, J., Richard, O. C., Triana, M. C., & Zhang, X. (2021). The performance impact of gender diversity in the top management team and board of directors: A multiteam systems approach. Human Resource Management, 61(2), 157–180.

Wu, M., & Wang, J. (2012). Developing a charismatic leadership model for Chinese organizations: The mediating role of loyalty to supervisors. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 23(19), 4069–4084.

Xi, M., He, W., Fehr, R., & Zhao, S. (2021). Feeling anxious and abusing low performers: A multilevel model of high performance work systems and abusive supervision. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 43(1), 91–111.

Xing, Y., & Liu, Y. (2015). Poetry and leadership in light of ambiguity and logic of appropriateness. Management and Organization Review, 11(4), 763–793.

Xing, Y., & Liu, Y. (2016). Linking leaders’ identity work and human resource management involvement: The case of sociocultural integration in Chinese mergers and acquisitions. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 27(20), 2550–2577.

Xing, Y., Liu, Y., Boojihawon, D. K., & Tarba, S. (2020a). Entrepreneurial team and strategic agility: A conceptual framework and research agenda. Human Resource Management Review, 30(1), 100696.

Xing, Y., Liu, Y., & Cooper, C. L. (2018). Local government as institutional entrepreneur: Collaborative partnerships in fostering regional entrepreneurship. British Journal of Management, 29(4), 670–690.

Xing, Y., Liu, Y., Tarba, S. Y., & Cooper, C. L. (2016). Intercultural influences on managing African employees of Chinese firms in Africa: Chinese managers’ HRM practices. International Business Review, 25(1), 28–41.

Xing, Y., Liu, Y., Tarba, S. Y., & Wood, G. (2020b). A cultural inquiry into ambidexterity in supervisor - subordinate relationship. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 31(2), 203–231.

Xing, Y., & Sims, D. (2012). Leadership, Daoist Wu Wei and reflexivity: Flow, self-protection and excuse in Chinese bank managers’ leadership practice. Management Learning, 43(1), 97–112.

Xing, Y., & Starik, M. (2017). Taoist leadership and employee green behaviour: A cultural and philosophical microfoundation of sustainability. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38(9), 1302–1319.

Yammarino, F. J., Dionne, S. D., Chun, J. U., & Dansereau, F. (2005). Leadership and levels of analysis: A state-of-the-science review. The Leadership Quarterly, 16(6), 879–919.

Zhang, M. J., Zhang, Y., & Law, K. S. (2021). Paradoxical leadership and innovation in work teams: The multilevel mediating role of ambidexterity and leader vision as a boundary condition. Academy of Management Journal.

Zhang, S., Hu, J., Chuang, C. H., & Chiao, Y. C. (2022a). Prototypical leaders reinforce efficacy beliefs: How and when leader–leader exchange relates to team effectiveness. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 43(6), 1136–1151.

Zhang, X., Fu, P., Xi, Y., Li, L., Xu, L., Cao, C., Li, G., Ma, L., & Ge, J. (2012). Understanding indigenous leadership research: Explication and Chinese examples. The Leadership Quarterly, 23(6), 1063–1079.

Zhang, X., Liu, Y., Tarba, S. Y., & Del Giudice, M. (2020). The micro-foundations of strategic ambidexterity: Chinese cross-border M&As, Mid-View thinking and integration management. International Business Review.

Zhang, Y., Zhang, Y., Law, K. S., & Zhou, J. (2022b). Paradoxical leadership, subjective ambivalence, and employee creativity: Effects of employee holistic thinking. Journal of Management Studies, 59(3), 695–723.

Zhang, Z.-X., Chen, Y.-R., & Ang, S. (2014). Business leadership in the Chinese context: Trends, findings, and implications. Management and Organization Review, 10(2), 199–221.

Zhu, C. J., & Warner, M. (2019). The emergence of human resource management in China: Convergence, divergence and contextualization. Human Resource Management Review, 29(1), 87–97.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Xing, Y., Liu, Y., Froese, F.J. et al. Advancing Chinese leadership research: review and future directions. Asian Bus Manage 22, 493–508 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41291-023-00224-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41291-023-00224-7