Abstract

Adopting a Civil Sphere Theory framework, we argue that Taiwan’s efforts at containing COVID-19 resulted from its “societalization” of pandemic unpreparedness, which was triggered by the 2003 SARS outbreak and resumed during the COVID-19 pandemic. Societalization refers to the process through which institutional failures are transformed into societal crises, with the civil sphere mobilized to discuss institutional dysfunctions, push for reforms, and attempt to democratize or otherwise transform institutional cultures. The societalization of pandemic unpreparedness in Taiwan led to reforms of the public health administration and the medical profession, thereby establishing state mechanisms for encouraging early responses and coordinating centralized command during outbreaks, and healthcare infrastructures for coordinating patient transfer and ensuring supplies of personal protective equipment. Reflections upon past uncivil acts among citizens motivated the civil sphere to foster a discourse of interdependence, redefining the boundaries between individual choices and civic virtues. Meanwhile, unaddressed challenges remained, including threats related to Taiwan’s political polarization. Our paper challenges the thesis of “authoritarian advantage,” highlighting how democratic societies can foster social preparedness to respond to crises. By illustrating how societalization can reach temporary closures but become reactivated subsequently, our study extends the theory of societalization by explicating its historical dimension.

Similar content being viewed by others

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to threaten and disrupt lives across the globe, Taiwan, a small island which has long endured diplomatic isolation on the international stage, is suddenly held up as the “gold standard” for how to contain this pandemic (Smith 2020). To date, among a population of 23 million, Taiwan has only 7 COVID-related deaths and roughly 500 confirmed cases. On June 7, 2020, Taiwan lifted most social distancing requirements, after maintaining a record of zero domestically transmitted cases for 56 consecutive days (or 4 incubation periods). It achieved this level of containment through relatively moderate measures—without any citywide lockdowns or large-scale business or school closures—despite its geographical proximity to and economic ties with China. How Taiwan beats the odds has made headlines in the New York Times, the Washington Post, the National Public Radio, ABC News, the Guardian, and Der Spiegel.

Many highlight Taiwan’s experiences during the 2003 Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) crisis as a key factor in its pandemic preparedness (Wang et al. 2020; Lin et al. 2020). However, Taiwan is not the only nation that endured suffering during the SARS outbreak. Yet other societies that arguably also learned their “SARS lessons,” such as China and Singapore, have had significantly larger outbreaks during the 2020 pandemic. Similarly, even as the confirmed cases and death tolls related to COVID-19 continue to rise in the U.S., it is far from certain that the U.S. will respond more effectively to the next pandemic. Beyond having experienced an epidemic in its recent past, what might explain Taiwan’s pandemic intervention achievements during the first wave of the COVID-19 outbreak?

Adopting a Civil Sphere Theory (CST) framework, we argue that Taiwan’s effective state-society collaboration to contain COVID-19 largely resulted from the “societalization” of pandemic unpreparedness. From a CST perspective, the “societalization” of a given problem occurs when an issue previously considered an institution-specific dysfunction is transformed into a societal crisis, thereby shifting the weight of the discussion from the jurisdiction of intra-institutional elites into the realm of the civil sphere (Alexander 2018). In Taiwan, the problem of pandemic unpreparedness was societalized in the aftermath of the SARS crisis, which led to institutional reforms in the public health administration and medical profession. During the COVID-19 outbreak, this societalization process resumed with an additional step: civil society reflected on its own pandemic unpreparedness, reinterpreting the boundaries between personal freedom and civic duties through the lenses of public health crises. Despite these reforms and reflections, there were also challenges in this process, including threats resulting from the persistent polarization of society.

Highlighting that democratic societies can foster institutional mechanisms for crisis response through the process of societalization, our findings challenge the thesis of “authoritarian advantage” for pandemic responses (Schwartz 2012). Facing the enormous challenges caused by the pandemic, which the state and society in the U.S. have thus far seemed incapable of addressing, the news media frequently publish the view that authoritarian regimes are perhaps better equipped to respond to the pandemic. Citing China’s draconian lockdown measures as examples of efficient state actions, reports in Bloomberg, CNN, the Wall Street Journal, the National Review, and the Atlantic, among others, worry aloud if democratic regimes can ever produce similar levels of efficacy in their COVID-19 battles (Brands 2020; Westcoot and Jiang 2020; Maçães 2020; Trofimov 2020; Diamond 2020). Meanwhile, a VOX article retorts that “authoritarian coronavirus supremacy” is a myth promoted by Chinese government propaganda (Beauchamp 2020). The Wall Street Journal article referenced above (Trofimov 2020) acknowledges the “superiority of the Chinese model” as a perspective promoted by the Chinese Communist Party’s mouthpiece, the People’s Daily. The seductive lure of the alleged authoritarian advantage—and the anxiety it elicits—appears to be brewing an existential crisis for democracy.

Social scientists mostly respond by emphasizing that the reality is more complex and nuanced, and rarely captured by over-simplified assumptions about the relationship between regime types and pandemic intervention outcomes. Scholars argue that some of the most successful examples of containing COVID-19 are found in democratic societies, such as South Korea and Denmark, while some of the worst examples, such as Iran, are authoritarian countries (Alon et al. 2020; Kavanagh and Singh 2020). Others point out that the pandemic, after all, originated from the lack of transparency and accountability in China (Kavanagh and Singh 2020). Some authors predict that any authoritarian advantage that appears in the short run will melt away in the long-term management of the COVID-19 crisis, including mental health and economic recovery (Cepaluni et al. 2020).

Still, as Kavanagh and Singh (2020) rightly observe, the distinguishing contrast between China’s success and America’s failure has emerged as a dominant COVID-19 narrative in the media, causing concerns that the public might become persuadable by the authoritarian advantage thesis, especially with the aid of misinformation campaigns (Alon et al. 2020). Reminiscent of Huntington’s (2006, p. 203) argument about military elites’ “highly modernizing and progressive role” during the mid-twentieth century,Footnote 1 some scholars indeed document an authoritarian advantage for pandemic response, attributed to authoritarian governments’ capacity for enforcing top-down commands, controlling the media, and ensuring public compliance (Cepaluni et al. 2020; Schwartz 2012). Overall, whether considered partially valid or largely misleading, the emerging narrative about authoritarian regimes’ functional superiority during the pandemic conflicts with key normative ideals held by most contemporary Western scholars. Concerned about and unnerved by a potential legitimation crisis for democracy, researchers urge democratic states to find ways to strengthen their state capacities (Schwartz 2012; Kavanagh and Singh 2020) and enhance social trust (Schwartz 2012).

These are worthy goals that are important for improving future crisis responses as well as preserving the normative ideals associated with democracy, such as civil liberty, transparency, and accountability. However, these studies typically say little about how we can achieve such goals. Indeed, the “how” question is key here: are there cultural mechanisms and social processes germane to democracy that can facilitate the institutional reforms and cultural transformations needed for enhancing state capacities and social trust? If so, what are they and how do they work? The model of societalization, as we will demonstrate, explicates the process of repairing social problems, including pandemic unpreparedness, by utilizing—rather than suspending—key social and cultural mechanisms in democratic societies. These mechanisms are integral structures of civil society, but civil society actors must activate these mechanisms, navigating through pushbacks, inertias, and sometimes limits of their own political imaginations.

Even though societalization creates pressures from the civil sphere for institutional reforms, these reforms do not guarantee problem-solving and may end instead with impasses or limited social change (Alexander 2018). Extending Alexander’s theoretical model, our study shows that, after reaching a temporary closure, societalization can become reactivated at subsequent eventful moments, potentially expanding the initial sets of reforms. Meanwhile, whether the first phase of societalization results in effective reforms, the process itself helps shape the collective memories of the triggering event, which inform, at least partially, whether and how societalization resumes at a later point. In this sense, our study extends the theory of societalization by explicating its historical dimension—a theoretical point we will return to in our conclusion.

Societalization: a Civil Sphere Theory approach

Democracy depends on a cultural foundation of civic solidarity, a sense of “we-ness” informing and informed by internal diversities and divisions. In real civil societies, which are necessarily hegemonic, such a normative ideal is never fully attained. Many scholars have debated the mechanisms, processes, and sometimes the very possibilities for approaching civic solidarity (Habermas 1989; Calhoun 1995; Fraser 1992; Lichterman and Eliasoph 2014; Rabinovitch 2001).

Civil Sphere Theory (CST) offers a theoretical framework for analyzing the tensions as well as mutual constitutions of diversity and solidarity in democratic societies. The civil sphere is conceptualized as the social realm in which civic solidarity is constantly renegotiated through diverse and changing understandings of the civil/uncivil divide (Alexander 2006). These debates can enrich instead of fragment civic solidarity because, in most (although not all) cases, holders of opposite opinions share the same cultural grammar, or binary code, for articulating democratic values. For example, agents of the American civil sphere tend to draw on the code of liberty, which sacralizes qualities such as rationality, autonomy, and equality, in opposition to hysteria, dependence, or hierarchy, while they debate vehemently over how such civil/uncivil qualities are manifested (Alexander 1992, 2006, 2018). Non-Western civil societies, including Taiwan, South Korea, and others, have imported the liberty code as well as incorporated variants of neo-Confucian or other collectivist values, which have developed into binary codes centered on the interdependence of the community or, alternatively, on the benevolence of the bureaucracy (Ku 2001; Lo and Bettinger 2009; Lo 2019; Alexander et al. 2019).

When the shared cultural grammars of the civil sphere are widely applied in the discussion of a crisis that has occurred in non-civil institutions (such as the church or the market), it launches the process of societalization. “Societalization” refers to the process by which an issue previously considered as an institution-specific dysfunction is transformed into a crisis threatening the whole society. This process is triggered when an institutional failure appears so damaging (e.g., the 2008 subprime mortgage crisis) that agents of the civil sphere attempt to reform the institution’s cultural values (e.g., efficiency) with moral codes of the civil sphere (e.g., equality). These attempts entail a cultural process of the civil sphere intervening in a non-civil institution to democratize the latter’s anticivil values, relations, or practices. Such civil sphere interventions in non-civil spheres constitute a form of “civil repair” (Alexander 2006, 2018).

In some instances, agents of the civil sphere are more modest in their requests. Instead of demanding institutional accountability according to civil values (e.g., equality), they simply hold the institution accountable to its own sphere-specific values (e.g., efficiency). When the public perceives that an institution has failed to deliver its promises even according to its own logic, an outraged public may mobilize to move the discussions about solutions from the confines of institutional expertise to the civil sphere. As such, the civil sphere “serves primarily as a realm of public discourse in which the media, among others, describe, explain, criticize, and seek to find ways out of the system crisis on behalf of the public” (Park 2019, p. 43). Building upon Alexander’s notion of civil repair, Park (2019) conceptualizes these civil society discussions about restoring institutional functions as attempts at “systemic repair.” Park writes, “Whereas civil repair targets mainly sustaining and enhancing autonomy, inclusion, and democracy, system repair intrudes into noncivil spheres for as fast a recovery as possible from functional damage. It does so…by activating the binary codes of the noncivil sphere in crisis to surmount the functional crisis” (2019, p. 43). Systemic repair is distinctly initiated by the civil sphere, on behalf of the civil sphere, to hold elites in a non-civil sphere accountable to their own institutional values.

It is important to note that corruptions and institutional failures are routine features for most institutions, yet institutional elites typically handle these institutional strains internally. But with societalization, “routine strains become sharply scrutinized, once lauded institutions are ferociously criticized, elites are threatened and punished, and far reaching institutional reforms are launched and sometimes achieved” (Alexander 2018, pp. 1049–1050). Through civil or systemic repairs, societalization results in attempts at institutional reforms, which are sometimes successful and can reconfigure the boundaries between the civil and non-civil spheres. Applying the framework of societalization to the Taiwan case, our analysis shows that it is not the SARS experience per se, but how the Taiwanese civil sphere acted upon this experience, that explains Taiwan’s success at containing the COVID-19 outbreak.

Background, methods, and data

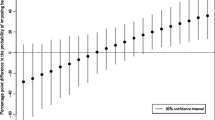

With its unique political history, the Taiwanese civil society has long struggled with a split national identification (Lo and Bettinger 2009), with some of the population embracing a pan-Chinese identity and a rising percentage embodying an independent Taiwanese identity. Recent data show significant changes in these patterns in the last two decades, as detailed in Fig. 1. But in 2019, a nationally representative survey indicated that, while 58.5% of the adult population in Taiwan self-identified as “Taiwanese” and only 3.5% self-identified as “Chinese,” 34.7% of the population continued to embrace a hybrid identification as both Taiwanese and Chinese (Election Study Center, National Chengchi University 2020). In other words, the patterns of national identification are evolving over time, but to date, it remains split. The pro-Taiwan and pro-China tensions have fueled continued political polarization on the island.

Changes in national identification in Taiwan.

To understand the civil sphere discourses about pandemic unpreparedness in this polarized society, we analyzed news editorials and columns published during the COVID-19 pandemic, in addition to relying on secondary materials reporting the discourses and reforms in the aftermath of the SARS crisis. We collected the editorials and columns from the two major Taiwanese newspapers on the opposite ends of the political spectrum, the pro-independence Liberty Times and the pro-unification United Daily. The commentaries in our sample addressed one or more of the three issues that stimulated avid public discussions during the pandemic: the 2003 SARS crisis, the mask-rationing system, and the chartered flights from Wuhan. We briefly describe the background for these events below.

The COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 reminded many Taiwanese of the 2003 SARS outbreak, which also spread from China to Taiwan. The first case in Taiwan emerged on March 14, 2003; by July 5, the WHO removed Taiwan from the list of infected areas. The outbreak sparked public panic when, on April 24, the Hoping Hospital was ordered by the Taipei City Government to undergo collective quarantine due to in-hospital infections. Cluster infections continued to occur in eight other medical facilities and several communities. Belatedly, the Taiwanese government finally launched a set of new measures and, by mid-May, gradually brought the epidemic under control. With 346 confirmed cases and 37 SARS-related deaths, Taiwan suffered the third largest SARS outbreak in the world by absolute numbers (with China being the largest). On a per capita basis, Taiwan suffered even more cases and fatalities than China (Schwartz 2012).

During the 2020 pandemic, the Taiwanese state responded in a dramatically different way. On January 24, 2020, nearly two months before the WHO declared COVID-19 a pandemic, the Taiwanese government banned mask export in anticipation of a shortage of supply. To increase mask supply, on January 31, the Ministry of Economic Affairs requisitioned mask production from domestic manufacturers. The National Health Command Center then launched a name-based rationing system for masks, which remained in effect from February 6 to June 1. Under this system, each individual could use their NHI (National Health Insurance) card to purchase two masks per week from over 6000 local pharmacies. The rationing system was updated in March and again in April, with increased quotas and other modifications. Our analysis is limited to the news articles commenting on the original mask-rationing system, which triggered the most intense debate.

Another intense public debate pertained to the chartered flights from Wuhan, the epicenter of the outbreak. On January 23, the first chartered flight carried 247 Taiwanese citizens and their Chinese spouses and children back to Taiwan. This humanitarian act became controversial when the Chinese authorities made last-minute changes to the boarding list and deviated from the bilateral agreement about pre-boarding and in-flight health precautions, causing great anxiety and discord in Taiwan. In response, the Taiwanese government postponed cross-strait negotiations for additional chartered flights from Wuhan, with two such flights finally landing in Taipei on March 10 and 11. Due to space limitation, we only analyzed news articles commenting on the first chartered flight.

In total, our sample included 66 editorials and 63 news commentaries, with roughly an even split between the two newspapers (see Table 1). These articles appeared between January 21, 2020 and May 5, 2020. We conducted two rounds of inductive coding to identify the key binary codes and narrative themes in these civil sphere discourses, although we bracket the discussion of binary codes in this paper.

The societalization of pandemic unpreparedness in Taiwan

Scholars have noted the Taiwanese state’s ability to recognize and swiftly respond to the early signs of the COVID-19 pandemic, manage the crisis with intra-government and state-profession coordination, and communicate related information with transparency. As early as January 20, 2020, with only sporadic cases reported from China, the Taiwan National Health Command Center (NHCC) activated its Central Epidemic Command Center (CECC), which then coordinated with other government agencies in fighting the pandemic. The CECC rapidly designed and implemented a list of 124 action items (Wang et al. 2020), including measures for border control, case identification and contact tracing, as well as quarantine requirements and other related guidelines, such as mask-wearing and social distancing measures. Upon the CECC’s request, the National Health Insurance Administration (NHIA) and the National Immigration Agency worked together to supplement the NHIA’s centralized cloud-based health records with patient travel histories, serving to alert hospitals to high-risk patients and allow the CECC to trace paths of infection (Wang et al. 2020; Lin et al. 2020). The CECC held daily briefings, which were rescheduled as weekly press conferences in early June, after the pandemic appeared sufficiently contained in Taiwan.

As we will illustrate below, the health administration’s remarkable precaution, coordination, and transparency during this pandemic represents institutional legacies co-produced by the civil society, the state, and the medical profession, through a long-term process of societalizing pandemic unpreparedness. This societalization process started after the SARS crisis and resumed in the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic, with some challenges remaining unaddressed.

Systemic and civil repairs of the public health administration and the medical profession

In sharp contrast to its image during the COVID-19 outbreak, the Taiwanese state, along with the medical profession, performed miserably during the 2003 SARS crisis. When the public decried these institutional failures, it triggered the societalization of pandemic unpreparedness, which in turn resulted in systemic repair of the public health administration and, to a lesser extent, civil repair of the medical profession.

The Taiwanese public health officials repeatedly missed the early signs of the SARS epidemic. When they finally responded, their actions were haphazard, uncoordinated, and resembling “afterthoughts rather than well-planned strategies” (Fan and Chen 2007, p. 151). As the SARS outbreak intensified, failures of the public health administration came to be viewed as a societal disaster by the public (Fan and Chen 2007). From a CST perspective, the institutional dysfunction was being societalized as a national crisis. For the most part, the civil sphere attempted a systemic repair, focusing on how the health authorities failed to live up to state bureaucracy’s core values, including preparedness and coordination. In particular, the Ministry of Health faced heavy criticisms in the media for not declaring SARS an infectious disease early enough, not providing hospitals with adequate personal protective equipment (PPE), and not coordinating with the Taipei mayor in shutting down the Hoping Hospital (Fan and Chen 2007; Kuhn 2003).

These criticisms eventually forced the Minister of Health and the Chief of the Taipei Municipal Health Bureau to resign. Under mounting pressure from the public, more reforms unfolded, including the establishment of the National Health Command Center (NHCC) in 2004, which was designed to coordinate future pandemic interventions (and did so in the 2020 outbreak). The new Minister of Health (later the vice president of Taiwan during the COVID-19 pandemic) implemented other reforms, including building isolation wards, increasing the national stockpile of PPE, and expanding virus research laboratories (Hernández and Horton 2020; Chuang et al. 2015; CDC (Taiwan) 2013). In short, responding to widespread civil society criticisms of its failed performance and demands for its systemic repair, the public health administration was pressured to establish mechanisms for facilitating better intra-government coordination and enacting precautionary principles for future outbreaks.

The medical profession also failed to adhere to its professional ethics during the SARS crisis. In the context of the state failures described above, many “gave up their battle in the name of individual or worker’s rights” (Ku and Wang 2004, p. 135). Some were caught on camera as they climbed out of windows to escape from the Hoping Hospital after the Taipei government placed it under lockdown—a government decision later condemned as ill-conceived and poorly executed. Many frontline medical workers resigned from their posts, and Taipei Mayor Ma Ying-Jeou accused them of being “traitors in a time of war” (Hanson 2020). Nurses and doctors organized many protests to demand respect for their lives and human rights. Protesting healthcare workers contended that requiring them to return to duty under ill-conceived government orders and without access to appropriate protective gears was tantamount to sending them to their deathbeds. These protests and interviews were widely reported in the media, intensifying the public’s distrust of the medical profession and its professional ethics (Ku and Wang 2004; Fan and Chen 2007).

After the SARS crisis, nurses and other medical groups took the initiative to engage in a civil repair of their profession. Many argued that uncivil values, specifically the outsized influence of market incentives in the hospital system, had led to unsafe working conditions and, accordingly, compromised their ability to perform their professional duty (Fan and Chen 2007; Tzeng 2003). Some medical professionals formed their own civic associations as a path toward institutional reform. For example, in the aftermath of SARS, the Association of Nurses Rights was organized to facilitate collective discussions about improving nurses’ working conditions so that demoralized nurses could renew their commitment to professionalism (Fan and Chen 2007). Other medical professionals launched discussions and workshops in the civil sphere, inviting both public intellectuals and social science scholars to discuss issues of medical ethics (Tsai and Jiang 2012; SARS Mental Health League 2003). On some occasions, medical workers explicitly invited “the people,” who “we are serving,” to help shape the approach for addressing the tensions between medical workers’ risk exposure and duty to care (Lin 2009, p. 189). As frontline medical workers attempted the civil repair of their profession by importing civil sphere values (e.g., individual rights) to reform the polluted qualities of the medical sphere (e.g., market incentives), they highlighted that the tension between medical ethics and unsafe working conditions should concern not only medical workers but the general public.

To some extent, medical workers’ attempts at civil repair in the sphere of healthcare dovetailed with some of the systemic repair conducted in the sphere of public health administration. In particular, the government’s efforts at expanding the stockpile of PPE and the number of isolation wards and negative pressure rooms addressed some of the concerns about occupational hazards during outbreaks. Along similar lines, medical professionals advocated for proposals to counter-balance the profit-driven logic of hospital administration with greater consideration for community well-being and healthcare workers’ chronic overwork. Concrete post-SARS reforms included the establishment of a patient-referral system to distribute patients across a hierarchical medical network (Cheng et al. 2014, p. 11), the allocation of greater resources to community and family medicine (Khu 2014, p. 2), and the expansion of targeted efforts within departments of infectious diseases (Hsu 2003). Tangible outcomes regarding professional ethics are more difficult to document, but as Taiwanese medical professionals received high praise during the COVID-19 outbreak, their professionalism seems to have been revitalized to some extent.

In short, with the state and professional dysfunctions during the SARS outbreak being societalized, widespread discussions in the civil sphere eventually led to relatively effective systemic repair of the public health administration and, to a lesser extent, attempts at civil repair of the medical profession. Many of these reforms became the foundation upon which the Taiwanese state was able to adopt a precautionary, coordinated, and transparent approach toward pandemic intervention during the COVID-19 outbreak, with the support of a committed and high-performing medical force. Indeed, throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, newspapers in Taiwan repeatedly praised the health authorities and medical professionals for reactivating and expanding their post-SARS reforms.

Civil repair of the civil society

Taiwan’s extensive post-SARS reforms notwithstanding, its societalization of pandemic unpreparedness was incomplete. It was not until the COVID-19 outbreak that the Taiwanese civil sphere undertook an additional step for the necessary civil repair of another sphere—the civil society itself.

Back in the 2003 SARS outbreak, Taiwanese citizens’ initial complacency was superseded by panic and selfishness. Many hoarded masks; others lied about their SARS-related symptoms and defied self-quarantine guidelines. Still others mobilized for NIMBY (not-in-my-backyard) protests, attempting to block SARS patients seeking medical care, return travelers from high-infected areas, or prevent SARS-related “public bad,” such as medical waste, from entering their communities (Ku and Wang 2004; Fan and Chen 2007).

However, in contrast to the aforementioned reforms in the state and the medical profession, there was only sporadic reflection upon ordinary citizens’ uncivil acts (Fan and Chen 2007; Chang 2005, pp. 6, 12–13). While a few news commentaries complained about the “ugliness of Taiwanese people” during the crisis, once the WHO removed Taiwan from the affected area list, most journalists, newspaper readers, and civic organizations dropped even the few projects and discussions on community-rebuilding or solidarity-revitalizing initiated during the SARS outbreak (Ku and Wang 2004).

In 2020, with the COVID-19 pandemic raging, journalists in Taiwan across the political spectrum united in their emphasis on societal collaboration. Commentators posited that even the most precautionary and well-coordinated state-led intervention efforts can only yield results with the collaboration of citizens. Indeed, newspapers from both sides urged the Taiwanese to exercise the civic virtues of responsibility and compassion by protecting one another through adhering to state-issued guidelines. From a CST perspective, we argue that agents of the civil sphere engaged in civil repair upon the civil sphere itself, reinterpreting the boundaries between personal choices and civic duties within a framework of community interdependence during the pandemic. In this instance, the contentious Taiwanese civil society departed from its “against the state” mode (Cohen and Arato 1992), in which civic solidarity is fostered through struggles against state surveillance, to mobilize for a “self-limiting” purpose (ibid.), in which civic solidarity is negotiated through bottom-up collaborations among diverse groups and sometimes with the state.Footnote 2

Examining the editorials and columns during the COVID-19 outbreak in the two major newspapers across the political divide, the pro-independence Liberty Times (LT) and the pro-unification United Daily (UD), we found both newspapers filled with reflections on the SARS experience. The similarity in these discussions across LT and UD was uncanny, considering their sharply polarized political stands and contrasting positions on almost every topic. Articles in both LT and UD revisited collective memories of SARS-related suffering caused by political incompetence and professional dysfunction and shared a sigh of relief as they recounted the lessons learned from Taiwan’s SARS trauma. Journalists often discussed post-SARS reforms as the foundation for Taiwan’s efforts to keep COVID-19 at bay, with both newspapers highlighting similar details of these institutional legacies, e.g., reformed public health infrastructure, experienced medical professionals and public health officials, and SARS-originated legal frameworks for pandemic management measures.Footnote 3 Drawing on collective memories shared across the political divide, journalists from both LT and UD not only accepted state guidelines as science-based measures but also accordingly framed citizens’ adherence to these guidelines as a form of civic virtue and an expression of civic solidarity.

Both LT and UD journalists praised Taiwanese citizens for the civic spirit they displayed with nearly universal mask-wearing in public transportation and other crowded public spaces and adherence to other inconvenient COVID-related regulations. These articles frequently characterized this civic spirit as indicating that citizens had learned from their “SARS mistakes.” A LT editorial from January 30, 2020 observed that “after experiencing the SARS storm… ordinary citizens must have learned [our lessons]. We don’t expect Taiwanese to repeat our society-wide panic state during the SARS crisis.”Footnote 4 Another LT column wrote: “Because of what Taiwan learned from the 2003 SARS outbreak,…Taiwanese people displayed a high degree of civic spirit this time, allowing for state-society co-mobilization to contain the spread of COVID-19” (emphasis ours).Footnote 5 Similarly, a UD editorial on January 23 urged citizens to adhere to the government’s travel restriction “even though such restrictions will cause individual inconvenience and displeasure.”Footnote 6 A LT column on April 24, 2020 reiterated that “the key [to containing the pandemic] lies in civic obligations and interdependence.”Footnote 7

Conversely, several articles alerted readers that not everyone had learned these lessons from history, citing examples of people lying about their symptoms, gathering in large crowds, or traveling overseas, and condemning these behaviors as a “gap in our line of defense” (LT, March 17, 2020).Footnote 8 A few journalists warned that there were new challenges that the Taiwanese civil society had not experienced during the SARS crisis. For instance, a LT editorial (February 18, 2020) argued that the misinformation campaigns on the internet could dismantle the civic solidarity fostered through and required for state-society collaboration in fighting the pandemic.Footnote 9 Responding to these worries, some commentaries demanded stricter government regulations, whereas others urged citizens to nurture greater civic awareness. The point is that in contrast to the NIMBY mentality and frantic searches for individual solutions during the SARS outbreak, Taiwanese citizens in the COVID-19 crisis displayed great moral conviction regarding mutual protection, for which journalists across the political divide vocally advocated.

Drawing on the theme of learning lessons from history, several commentaries pointed out that, because of the SARS experience, mask-wearing was seen as a civic duty during the pandemic in Taiwan, whereas the same mandate was resisted in the name of individual freedom in the U.S. (e.g., LT, April 14, 2020; UD, March 22, 2020).Footnote 10 These articles conveyed Taiwanese civil society’s understandings of and capacities for civic virtues that had been shaped by its past, and in particular, the SARS crisis. By extension, some commentators contemplated how the current efforts at containing COVID-19 would shape the future of Taiwanese civil society, accordingly urging citizens to consider investing in the public good for the long term. A few columns called for the civil sphere to consider possibilities for an even more extensive state-society network of pandemic management and a deeper reexamination of its citizens’ civic virtues from the perspective of one’s obligations to future generations. “In the spirit of civic duties,” the LT suggested, “…we should take this opportunity to reconsider how to build a more sustainable society, in terms of food security, medical resources, and so forth” (LT, April 24, 2020; see also UD, February 29, 2020).Footnote 11 While these discussions did not constitute a dominant theme in the civil sphere discourse about the connections between SARS memories and the COVID-19 crisis, we view them as forming a significant subplot in this civil sphere discourse, which began to situate civic virtues in the context of historical continuity and citizens’ interdependence across generations.

Threats of populism

As with other cases of societalization, disruptions to civil repair were unavoidable. In the example of the mask-rationing system discussed below, political polarizations prompted the United Daily to advocate for populist demands, threatening to stall the “self-limiting” mobilization in the civil repair of an uncivil public.

Early in the epidemic, the Taiwanese government implemented the mask-rationing system as a mechanism to ensure the availability of facial masks. Over time, public health administrators adapted relevant regulations in response to a fluid and rapidly evolving environment of supply and demand. As the local supply for masks gradually increased, the quota for each individual became more generous. Taiwan even began to donate millions of masks to the international community as an act of compassion and a tool for diplomacy.

Commenting on these changes, most editorials and columns in the Liberty Times praised the government for its responsiveness. In contrast, the United Daily repeatedly complained that these policy adaptations exemplified incoherent, self-contradictory state actions and criticized the government for not producing enough masks for everyone to purchase at will. In a sense, the contrasting stands reflected the positions of the two papers in a polarized Taiwanese society, with LT and UD generally publishing along the pro-independence versus pro-unification fault-line. While, as discussed above, their shared collective memories of SARS marked a rare exception, their divergent stands on the mask-rationing system might appear as an unremarkable example of their general publishing patterns. But closer examinations of UD’s criticisms of the mask-rationing system suggest that UD’s commentaries represented a populist attempt at civil repair. The United Daily spun a discourse of “making the people happy,” which reified “the people” as possessing a singular will (demanding more masks regardless of its social costs), ignored competing voices (from masks producers, healthcare professionals, diplomats, and others), and over-moralized policy stability in the rapidly changing context of the pandemic.

For example, on February 1, 2020, a UD column complained that the masks sold through the rationing system, priced at NT$6 (about $0.20) apiece, were “too expensive, and the people still cannot find all the masks they need” (emphasis ours).Footnote 12 A UD editorial criticized that “although our nation has really lowered the transmission rate,…the people still need to stand in long lines for masks” (April 11, 2020; emphasis ours).Footnote 13 “The people never enjoyed the feeling that there are plenty of masks” (April 10, 2020; emphasis ours).Footnote 14 Considering that the rationing system was implemented amidst a global shortage of masks, these complaints, constructed solely on the foundation that some “people” were unhappy, were hardly reasonable.

Similarly, many UD commentaries criticized the government for being inconsistent with its mask policies, as these policies contained different components or were adapted to changing contexts. Some UD articles accused the government of causing confusion because “the government advocated for mask-wearing as a general principle…but the Ministry of Health and Welfare also explained that this principle mainly applies to those with underlying conditions, entering crowded or poorly ventilated spaces, or going into hospitals and other public buildings” (February 2, 2020).Footnote 15 “At first we went to the supermarket to buy masks, then, under the name-based rationing system, we had to go to the pharmacies to buy them. The people cursed these changes” (February 4, 2020; emphasis ours).Footnote 16 Over time, as the supply for masks became more stable, increasing each individual’s quota was no longer the top concern in the civil sphere. Medical and lay groups advocated for disinfecting masks for multiple usages to minimize the impact on the environment and to increase the supply for high-risk populations. The Tsai administration also proceeded to donate masks to the U.S., Canada, the EU, and other allies, as a diplomatic strategy to facilitate Taiwan’s international participation as Taiwan is excluded from most international forums, including the WHO. These civic voices and diplomatic strategies were condemned in most UD commentaries because “some people in Taiwan still cannot get all the masks they want.” By elevating the interest of a segment of the public in the name of “the people” at the expense of competing priorities, these demands promoted populist rhetoric and accordingly threatened to disrupt the emergence of a “self-limiting” civic solidarity based on tolerance and interdependence.

The Liberty Times editorials and columns offered an almost completely opposite appraisal of the same policies and practices related to the mask-rationing system. Most importantly, LT explicitly criticized UD’s writings on this topic for being populist. Many LT articles engaged in criticizing the criticisms published in UD (and other similar media), cautioning that the latter was using the values of liberty (e.g., individual rights) and bureaucracy (e.g., efficiency) in highly illiberal and uncaring ways (e.g., insincerely, ignorantly, or selfishly). Similar to their discussions of the SARS legacies, many LT articles about the mask-rationing system emphasized the theme of civic virtues, arguing that, during a pandemic, individual rights and bureaucratic efficiency should be situated in the framework of the interdependence and mutual protection of the community. In contrast, the theme of civic virtues was completely absent in the UD comments on the mask-rationing system.

At the end, with the mask-rationing system receiving high approval ratings domestically and significant praise overseas, the United Daily abandoned this conversation and their comments on the topic tapered off. Still, the UD’s populist imaginations for pandemic interventions threatened to push the state–society collaboration unproductively toward an overly narrow set of considerations. These populist demands seemed to give way when countered by the LT’s alternative civil discourse envisioning pandemic management mechanisms as addressing diverse and evolving social needs. But the danger of populism persisted. If the high level of public support for the mask-rationing system had not materialized, it is not clear that LT’s counter-arguments alone would have been sufficient to redirect UD’s populist discourse.

Missed conversations about scientific uncertainty

The civil repair for negotiating a “self-limiting” civic solidarity faced other limits due to the polarization of the Taiwanese civil sphere. While with their shared SARS memories, the two sides temporarily consolidated a moral discourse of the interdependence of the community, the Taiwanese civil society remained deeply divided over the boundaries of this community, specifically in terms of its relationship with China. When it became front and center in the conversation, the issue about community boundaries caused a gridlock for the civil repair of the civil sphere’s own pandemic unpreparedness, as illustrated in the debate over how to evacuate the Taiwanese in Wuhan.

Most LT editorials and columns on this topic coalesce around the theme of prioritizing the health of the residents in Taiwan. These commentators argued that the Taiwanese government must strictly control the procedures of the chartered flights, prioritizing those with medical and other needs while holding off on less urgent cases. Several authors referenced a petition drafted by groups of medical professionals that favored strict controls for the chartered flights to prevent Taiwan’s medical system from collapsing. This petition was described in the LT as an expression of civic solidarity that served to reinforce the boundaries of the community.

Defining this community against China’s aggression, LT authors were highly critical of China’s delays in the chartered flight negotiations, last-minute changes to the list of evacuees, and deviations from the safety requirements specified by the Taiwanese public health officials. These authors argued that China prioritized its political agenda of asserting dominance over Taiwan at the expense of public health concerns. Several authors further charged that the evacuees that later tested positive for COVID-19 (and who were not on the original agreed-upon list) were smuggled onto the plane by the Chinese authorities deliberately, to function as a Trojan horse that would sabotage Taiwan’s pandemic containment. Authors further questioned the political agenda behind the Taiwanese journalists who minimized the threat of this “Trojan horse” (e.g., LT, February 7, 2020; LT, February 21, 2020).Footnote 17

Editorials and columns in the United Daily countered this position by arguing that the “Trojan horse” could be safely contained by government efficiency and precaution, such as testing, quarantine, and contact tracing. As this debate became increasingly polarized, UD authors became more defensive. They argued that the “Trojan horse” was not so deadly after all (e.g., UD, February 23, 2020),Footnote 18 that compassion should outweigh any such concerns (e.g., UD, February 6, 2020),Footnote 19 and that discussions of limited medical resources were merely a politicized discourse to further the Tsai Administration’s anti-China agenda. UD commentaries labeled the civic groups advocating for stricter control over the chartered flights callous and hateful, condemning their sense of community as exclusionary and discriminatory toward the Taiwanese in China and their Chinese families (e.g., UD, February 12, 2020, February 22, 2020, February 26, 2020).Footnote 20

These themes in UD and LT were almost entirely oppositional to each other, reflecting their unresolvable tensions regarding the boundaries of the Taiwanese community. LT defined this community primarily as consisting of the 23 million residents in Taiwan. UD regarded how the government and the Taiwanese civil society handled the chartered flights as a litmus test for whether they accepted the Taiwanese in China as equal members of the community. Without a doubt, chartered flights from the epicenter of the pandemic carried considerable risks for spreading the virus in Taiwan. The efforts to manage such risks, in turn, would impose certain social costs, with different options implying different costs on different stakeholders. Balancing the concerns of risk management and social cost would accentuate the scientific uncertainties in all available options, thereby inviting different groups to engage in the evaluations of alternatives. But with the over-politicization of the issue, the two sides never had a full-fledged conversation about the scientific uncertainties that they were facing.

Granted, discussions of risk management and social cost are necessarily political to the extent that civil society discourses are always hegemonic. But cast in the polarized pro-Taiwan versus pro-China framework, the position of the Taiwanese in China became hyper-politicized. Instead of proceeding from an acknowledgement of the scientific ambiguity involved, each side viewed the other side’s proposal as purely a politically motivated agenda. In the end, scientific uncertainty was eclipsed by ideological certainty, resulting in the largely missed opportunity for in-depth conversations about different approaches to balance risk management and social cost.

Conclusion

Scholars have attributed Taiwan’s relative success at containing the COVID-19 pandemic to its SARS experience. Our paper qualified this observation by arguing that the key lies not in the SARS experience per se, but in the “societalization” of pandemic unpreparedness. Societalization refers to the process through which institutional failures are transformed into societal crises, with the civil sphere actively mobilized to discuss related institutional dysfunctions, push for reforms, and attempt to democratize or otherwise transform institutional cultures. In Taiwan, the societalization of pandemic unpreparedness was both non-linear and multi-sphere, leading to civil and systemic repairs of the public health administration, the medical profession, and, with a time lag, the civil society itself. These reform efforts put in place government mechanisms for encouraging early responses and coordinating centralized command during outbreaks, as well as healthcare infrastructures for coordinating patient transfer, caring for the infected, and ensuring supplies for PPE for medical workers. After several years of delay, reflections upon past uncivil acts among citizens motivated the civil sphere to foster a discourse of interdependence and self-limitation, redefining the boundaries between individual choices and civic virtues through the lenses of pandemic intervention.

Societalization, however, tends to be ineffective in polarized democracies, as the opposing sides are inclined to mobilize against each other rather than come together in demanding reforms from failing institutions (Alexander 2018). In the polarized Taiwanese society, the civil sphere managed to foster a rare alliance in the societalization of pandemic unpreparedness, yet political polarization did impose limits on the democratic potential of these efforts. Populist demands surfaced on occasion, threatening to disrupt the discourse of civic interdependence. Debates over plans for evacuating the Taiwanese from Wuhan touched the most sensitive nerve in this society with split national identifications, resulting in both sides abandoning any self-reflections on the scientific ambiguity of their own proposals.

This missed conversation is worrisome. Without undermining the factual truth of specific scientific findings, scientific projects and policies are inevitably shaped by politics, cultural assumptions, and value systems. When making decisions on the basis of such scientific uncertainty, especially amidst the high-risk context of pandemics, governments and citizens are called upon to “decide about the undecidable” (Beck 1992), making it essential to deliberate among scientists, lay experts, and different stakeholders (Wynne 1992; Jasanoff 2012). Facing the unknown futures with COVID-19 and other pandemics, the Taiwanese civil sphere is yet to nurture in its participants a robust social reflexivity for recognizing and deliberating over the trade-offs between risk management and social cost in different proposals, including (or especially) the ones that seem most politically palatable. In short, the societalization of pandemic unpreparedness in Taiwan culminated in relatively effective reforms in several domains at different points in time, but not without lingering challenges.

At a theoretical level, our study highlights and elaborates on a historical dimension that, thus far, has remained implicit in the societalization model. Specifically, we have demonstrated that, after reaching a temporary closure, societalization can resume at subsequent eventful moments. Legacies from earlier phases of societalization shape subsequent efforts of re-societalization, while also being expanded, redefined, or both, in the process. As such, the civil and systemic repairs in response to societal crises not only engender institutional changes, but equally importantly serve to structure the civil sphere’s memories of injustice, sculpting the social and cultural landscape of the local civil sphere.

Specifically, despite a relatively low death toll (37) compared to other disasters, the SARS outbreak was experienced as a “cultural trauma” (Alexander 2012) in Taiwan, with an anxiety-ridden and emotionally fraught civil sphere asking—to paraphrase Eyerman (2015)—“Is this Taiwan?” The societalization of the SARS crisis scripted a trauma narrative centering on political incompetencies, professional dysfunctions, and an eventual redemption through ex post facto institutional reforms. When reactivated by the COVID-19 crisis, this trauma narrative at least partially informed civil society discussions about the new coronavirus. In a “never SARS again” trope, major newspapers in Taiwan’s polarized civil sphere united in fostering a discourse of societal collaboration and civic interdependence, achieving, as we have described, a delayed civil repair of civil society itself. This delayed civil repair, absent in the first phase of societalization, broadened the SARS trauma narrative with an additional plotline about competing roles of citizens, who are no longer cast solely as victims (as in the original SARS trauma narrative) but also potential heroes (if religiously wearing masks) and villains (if defying quarantine orders). In this vein, we join recent endeavors to conceptualize the connections between CST and theories of collective memories (Binder 2021; Alexander 2021), showing how meanings of cultural trauma are continually negotiated through civil sphere processes and, conversely, how such cultural legacies inform the future unfolding of civil sphere processes.Footnote 21

In sum, without overlooking its challenges or predicting its future performance should there be a second-wave COVID outbreak, Taiwan has done relatively well with learning from its past. But the SARS experience would not have prepared Taiwan for the current COVID-19 outbreak the way it did if its civil sphere had not engaged in societalizing pandemic unpreparedness, or if its public health administration, medical profession, and civil society itself had not been pushed accordingly to undertake reforms and reflections. The Taiwan case serves to illustrate the processes through which democratic societies can consolidate institutional mechanisms and societal preparedness for pandemic intervention. Compared to the alleged “authoritarian advantage” of crisis responses, the bottom-up impetus of societalization appears to demand greater accountability from the state and the profession and nurtures a greater self-awareness of civic interdependence among citizens. Our case study, then, addresses the worry that “authoritarianism is more effective but less desirable,” precisely by demonstrating that civil and systemic repairs can function as effective and democratic mechanisms for repairing social ills. At the same time, we must not presume that history and democracy will automatically guarantee pandemic preparedness. Indeed, unless civil society actors engage in serious systemic and civil repairs after the COVID-19 pandemic, the U.S. and other heavily impacted democratic societies are unlikely to respond well to the next outbreak. Perhaps how Taiwan learned its SARS lessons is instructive for other societies in learning from their COVID-19 crises.

Notes

Fukuyama (2006, p. xiii) characterizes Huntington’s argument as “the groundwork for a development strategy that came to be called the ‘authoritarian transition,’ whereby a modernizing dictatorship provided political order, a rule of law, and the conditions for successful economic and social development.”

Cohen and Arato (1992, p. 509) argue that civil society is “the target as well as the terrain of collective action.” As the terrain, civil society is the space where citizens mobilize to resist state power. As the target, practices of exclusion and cultural biases among social groups are recognized as problems requiring fixing. For Taiwan, as a young democracy, early social movements quite understandably focused on resisting an authoritarian state and its legacies that lingered long after democratic elections became institutionalized. Later on, civil society actors began to see that their fight against authoritarianism and its ideological and institutional remnants provided only a shallow basis for civic solidarity. To deepen the foundation for a sense of “we-ness,” civil society actors must nurture reflexivity, become more inclusive, and sometimes compromise with groups with different stands. Such civic engagement, in Cohen and Arato’s terms, illustrates a “self-limiting” mode of civil society.

One key difference in these SARS-related reflections across LT and UD did stand out. The articles in LT linked Taiwan’s experiences with SARS to the current government’s efficiency, coordination, transparency, and precaution. Editorials and columns in UD acknowledged the same connection, but limited its praise for public health administrators in the government. Meanwhile, several UD editorials criticized the Tsai Administration for lacking efficiency and coordination in utilizing the legal framework made available during the SARS crisis to take swift actions for economic stimulation.

Source: https://talk.ltn.com.tw/article/paper/1348483 (accessed June 25, 2020).

Source: https://talk.ltn.com.tw/article/breakingnews/3101599 (accessed June 25, 2020). All translations are ours, unless indicated otherwise.

Source: https://udn.com/news/story/7338/4303890 (accessed June 25, 2020).

Source: https://talk.ltn.com.tw/article/breakingnews/3144493 (accessed June 25, 2020).

Source: https://talk.ltn.com.tw/article/breakingnews/3102007 (accessed June 25, 2020).

Source: https://talk.ltn.com.tw/article/paper/1352801 (accessed June 25, 2020).

Sources: https://talk.ltn.com.tw/article/paper/1365751 and https://udn.com/news/story/7338/4433516 (accessed June 25, 2020).

Sources: https://talk.ltn.com.tw/article/breakingnews/3144493 and https://udn.com/news/story/7338/4378416 (accessed June 25, 2020).

Source: https://udn.com/news/story/7338/4314900 (accessed June 25, 2020).

Source: https://udn.com/news/story/7338/4483672 (accessed June 25, 2020).

Source: https://udn.com/news/story/7338/4480990 (accessed June 25, 2020).

Source: https://udn.com/news/story/7338/4316403 (accessed June 25, 2020).

Source: https://udn.com/news/story/120958/4320736 (accessed June 25, 2020).

Sources: https://talk.ltn.com.tw/article/paper/1350271 and https://talk.ltn.com.tw/article/paper/1353421 (accessed June 25, 2020).

Source: https://udn.com/news/story/7338/4363913 (accessed June 25, 2020).

Source: https://udn.com/news/story/7338/4324712 (accessed June 25, 2020).

Sources: https://udn.com/news/story/7338/4337930, https://udn.com/news/story/7339/4362101, and https://udn.com/news/story/7338/4370992 (accessed June 25, 2020).

Alexander’s theorization of cultural trauma gestures toward a similar argument, as he points out that even after a trauma narrative is no longer deeply preoccupying, it nonetheless “remains as a fundamental resource for resolving future social problems and disturbances of collective consciousness” (Alexander 2012, p. 27).

References

Alexander, J.C. 1992. Citizen and Enemy as Symbolic Classification: On the Polarizing Discourse of Civil Society. In Where Culture Talks: Exclusion and the Making of Society, ed. Marcel Fournier and Michèle Lamont, 289–308. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Alexander, J.C. 2006. The Civil Sphere. New York: Oxford University Press.

Alexander, J.C. 2012. Trauma: A social theory. Malden: Polity.

Alexander, J.C. 2018. The Societalization of Social Problems: Church Pedophilia, Phone Hacking, and the Financial Crisis. American Sociological Review 83 (6): 1049–1078.

Alexander, J.C., D. Palmer, S. Park, and A. Ku (eds.). 2019. The Civil Sphere in East Asia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Alexander, J.C. 2021. Introduction: The Populist Continuum from Within the Civil Sphere to Outside It. In Populism in the Civil Sphere, eds. J.C. Alexander, P. Kivisto, and G. Sciortino, 1–16. Cambridge: Polity Press (forthcoming).

Alon, I., M. Farrell, and S. Li. 2020. Regime Type and COVID-19 Response. FIIB Business Review. https://doi.org/10.1177/2319714520928884. Accessed July 23, 2020.

Beck, U. 1992. Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity. London: Sage.

Binder, W. 2021. Memory Culture, the Civil Sphere, and Right-Wing Populism in Germany: The Resistible Rise of the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD). In Populism in the Civil Sphere, eds. Jeffrey C. Alexander, Peter Kivisto, and Giuseppe Sciortino, 178–204. Cambridge: Polity Press (forthcoming).

Beauchamp, Z. 2020. The myth of authoritarian coronavirus supremacy. VOX, March 26, https://www.vox.com/2020/3/26/21184238/coronavirus-china-authoritarian-system-democracy. Accessed August 5, 2020.

Brands, H. 2020. Coronavirus is China’s Chance to Weaken the Liberal Order. Bloomberg, March 17, https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2020-03-17/coronavirus-is-making-china-s-model-look-better-and-better. Accessed August 5, 2020.

Calhoun, C. 1995. Nationalism and Difference: The Politics of Identity Writ Large. In Critical Social Theory, ed. Craig Calhoun, 231–282. Cambridge: Blackwell.

Center for Disease Control (Taiwan). 2013. A Decade After SARS: Lessons Learned and Prepareness. https://www.cdc.gov.tw/En/InfectionReport/Info/g6GB-Fg4GqQRYhF8jHY7Gw?infoId=02ZLxQZEE632VuP72wCCgQ. Accessed June 23, 2020 (in Chinese).

Cepaluni, G., M. Dorsch, and R. Branyiczki. 2020. Political Regimes and Deaths in the Early Stages of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3586767. Accessed July 23, 2020.

Chang, L.Y. 2005. Social and Economic Impact of SARS Outbreak: A Comparative study. Report No. NSC92-2420-H-001-012-KC. National Science Council of Taiwan ROC (in Chinese).

Cheng, W.S., C.H. Chen, and C.Y. Chen. 2014. Education and Training for an Accountable Family Physician. In The Education and Training for an Accountable Family Physician—The Future Challenge, ed. T.G. Khu, 11–18. Taiwan Association of Family Medicine: Taipei. (in Chinese).

Chuang, S.W., et al. 2015. Establishment of a System Dynamics Simulation Model for Decision Support of Preparedness of Epidemic Prevention Materials in Infectious Diseases. Report No. MOHW104-CDC-C-114-122103. Ministry of Health and Welfare (Taiwan) (in Chinese).

Cohen, J., and A. Arato. 1992. Civil Society and Political Theory. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Diamond, L. 2020. America’s COVID-19 Disaster is a Setback for Democracy. The Atlantic, May 6, https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/04/americas-covid-19-disaster-setback-democracy/610102. Accessed August 5, 2020.

Election Study Center, National Chengchi University. 2020. Changes in the Taiwanese/Chinese Identity of Taiwanese as Tracked in Surveys by the Election Study Center, NCCU (1992–2019). https://esc.nccu.edu.tw/course/news.php?Sn=166. Accessed June 24, 2020.

Eyerman, R. 2015. Is This America? Katrina as Cultural Trauma. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Fan, Y., and M.C. Chen. 2007. The Weakness of a Post-Authoritarian Democratic Society: Reflections upon Taiwan’s Societal Crisis During the SARS Outbreak. In SARS: Reception and Interpretations in Three Chinese Cities, ed. D. Davis and H.F. Siu, 147–164. New York: Routledge.

Fraser, N. 1992. Rethinking the Public Sphere: A Contribution to the Critique of Actually Existing Democracy. In Habermas and the Public Sphere, ed. C. Calhoun, 109–142. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Fukuyama, F. 2006. Foreword. In Political Order in Changing Societies, ed. Samuel P. Huntington, xi–xviii. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Habermas, J. 1989 [1962]. The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere (trans: Burger, Thomas with the assistance of Lawrence, Frederick). Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Hanson, R. 2020. Life across SARS and COVID-19 in Taiwan. Asia Media Center, May 6, https://www.asiamediacentre.org.nz/features/life-across-sars-and-covid-19/. Accessed June 22, 2020.

Hernández, J.C., and C. Horton. 2020. Taiwan’s Weapon Against Coronavirus: An Epidemiologist as Vice President. The New York Times, May 9, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/09/world/asia/taiwan-vice-president-coronavirus.html. Accessed June 21, 2020.

Hsu, C.S. 2003. Anticipation and Advice on Medical Reform After SARS. Infection Control Journal 13: 243–246. (in Chinese).

Huntington, S.P. 2006 [1968]. Political Order in Changing Societies. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Kavanagh, M.M., and R. Singh. 2020. Democracy, Capacity, and Coercion in Pandemic Response—COVID 19 in Comparative Political Perspective. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. https://doi.org/10.1215/03616878-8641530.

Jasanoff, S. 2012. Science and Public Reason. London: Routledge.

Khu, T.G. (ed.). 2014. The Education and Training for an Accountable Family Physician—The Future Challenge. Taiwan Association of Family Medicine: Taipei. (in Chinese).

Ku, A.S. 2001. The ‘Public’ Up Against the State—Credibility Crisis and Narrative Cracks in Post-colonial Hong Kong. Theory, Culture and Society 18 (1): 121–144.

Ku, A.S., and H.L. Wang. 2004. The Making and Unmaking of Civic Solidarity: Comparing the Coping Responses of Civil Societies in Hong Kong and Taiwan during the SARS Crises. Asian Perspective 28 (1): 121–147.

Kuhn, A. 2003. Taiwan’s Health Minister Steps Down as Anger Spreads over SARS. LA Times, March 17, https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2003-may-17-fg-chisars17-story.html. Accessed June 21, 2020.

Lichterman, P., and N. Eliasoph. 2014. Civic Action. American Journal of Sociology 120 (3): 798–863.

Lin, C., W.E. Braund, J. Auerbach, J. Chou, et al. 2020. Policy Decisions and Use of Information Technology to Fight COVID-19 Taiwan. Emerging Infectious Diseases 26 (7): 1506–1512.

Lin, K.M. 2009. State, Civil Society, and Deliberative Democracy: The Practices of Consensus Conferences in Taiwan. Taiwanese Sociology 17: 161–217.

Lo, M.C.M. 2019. Cultures of Democracy: A Civil Society Approach. In Routledge Handbook of Cultural Sociology, 2nd ed, ed. L. Grindstaff, M.C.M. Lo, and J.R. Hall, 497–505. London: Routledge.

Lo, M.C.M., and C.P. Bettinger. 2009. Civic Solidarity in Hong Kong and Taiwan. The China Quarterly 197: 183–203.

Maçães, B. 2020. Coronavirus and the Clash of Civilizations. National Review, March 10, https://www.nationalreview.com/2020/03/coronavirus-and-the-clash-of-civilizations/. Accessed August 5, 2020.

Park, S. 2019. System Crisis and the Civil Sphere: Media Discourse on the Crisis of Education in South Korea. In The Civil Sphere in East Asia, ed. J. Alexander, D. Palmer, S. Park, and A. Ku, 38–59. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rabinovitch, E. 2001. Gender and the Public Sphere: Alternative Forms of Integration in Nineteenth-Century America. Sociological Theory 19: 344–370.

SARS Mental Health League. 2003. Records of the First Meeting for SARS Mental Health League on 13 May 2003. https://sars.heart.net.tw/record1.doc. Accessed June 22, 2020.

Schwartz, J. 2012. Compensating for the ‘Authoritarian Advantage’ in Crisis Response: A Comparative Case Study of SARS Pandemic Responses in China and Taiwan. Journal of Chinese Political Science 17 (3): 313–331.

Smith, N. 2020. Taiwan Sets Gold Standard on Epidemic Response to Keep Infection Rates Low. The Telegraph, March 6, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2020/03/06/taiwan-sets-gold-standard-epidemic-response-keep-infection-rates/. Accessed June 22, 2020.

Tsai, F.C., and Y.H. Jiang (eds.). 2012. Diseases and Society: Medical and Humanistic Reflections of Taiwan’s Experience of the SARS Storm. Taipei: National Taiwan University Hospital. (in Chinese).

Trofimov, Y. 2020. Democracy, Dictatorship, Disease: The West Takes Its Turn with Coronavirus. The Wall Street Journal, March 8, https://www.wsj.com/articles/democracy-dictatorship-disease-the-west-takes-its-turn-with-coronavirus-11583701472. Accessed August 5, 2020.

Tzeng, H.M. 2003. Fighting the SARS Epidemic in Taiwan: A Nursing Perspective. The Journal of Nursing Administration 33 (11): 565–567.

Wang, C.J., C.Y. Ng, and R.H. Brook. 2020. Response to COVID-19 in Taiwan: Big Data Analytics, New Technology, and Proactive Testing. JAMA, 3 March. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2762689. Accessed June 21, 2020.

Westcoot, B., and S. Jiang. 2020. Chinese Diplomat Promotes Conspiracy Theory that US Military Brought Coronavirus to Wuhan. CNN, March 13, https://www.cnn.com/2020/03/13/asia/china-coronavirus-us-lijian-zhao-intl-hnk/index.html. Accessed August 5, 2020.

Wynne, B. 1992. Uncertainty and Environmental Learning: Reconceiving Science and Policy in the Preventive Paradigm. Global Environmental Change 2 (2): 111–127.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lo, MC.M., Hsieh, HY. The “Societalization” of pandemic unpreparedness: lessons from Taiwan’s COVID response. Am J Cult Sociol 8, 384–404 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41290-020-00113-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41290-020-00113-y