Abstract

Despite growing informality in developing economies, identifying correlates of informality continues to be a challenge due to multiple definitions of informality as well as data limitations. In order to explain the determinants of informality, the authors use two operational definitions of informality, namely ‘informal sector’ and ‘informal employment’, based on enterprise characteristics and employment characteristics, respectively. Using unit-level data from a nationally representative dataset, the authors find that, irrespective of how informality is defined, workers’ education, vocational training and gender play a significant role in determining participation in the informal labour market. The results of this study are robust to correction for selection bias and controlling for regional variations. The findings emphasise the need to restructure skill development programmes to account for the heterogeneity of informal workers.

Résumé

Malgré l’augmentation du travail informel dans les économies en développement, l’identification des corrélats de l’informalité continue d’être un défi en raison des définitions multiples de l’informalité ainsi que des limites des données. Afin d’expliquer les déterminants du travail informel, les auteurs utilisent deux définitions opérationnelles de l’informalité, à savoir « secteur informel » et « emploi informel » selon les caractéristiques respectives de l’entreprise et de l’emploi. Grâce aux données unitaires provenant d’un ensemble de données représentatives au niveau national, les auteurs constatent que, quelle que soit la définition de l’informalité, l’éducation des travailleurs, la formation professionnelle et le sexe jouent un rôle important dans la détermination de la participation au marché du travail informel. Les résultats de cette étude sont robustes quant à la correction du biais de sélection et au contrôle des variations régionales. Les résultats soulignent la nécessité de restructurer les programmes de développement des compétences pour prendre en compte l’hétérogénéité des travailleurs informels.

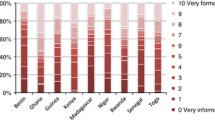

Source Authors’ own calculation based on 55th, 61st and 68th round of NSSO employment–unemployment survey, unit-level data

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Unit-level data pertains to data from the ultimate stage of the large scale multi-stage sample survey: household level. The non-agricultural sector comprises enterprises engaged in mining and quarrying, fisheries, and enterprises in the manufacturing and service sectors.

Informality or informal work refers to both informal sector employment and informal employment.

The ICLS is an ILO meeting that takes place every 5 years. Participants include experts from governments, as well as from workers’ and employers’ organisations.

According to the 17th ICLS, ‘household’ includes households producing goods exclusively for their own final use (e.g. subsistence farming), as well as households employing paid domestic workers (maids, drivers etc.)

The reference periods used by the NSSO are: the usual principal activity status (UPAS) pertaining to the activity for the major part of a year with a reference period of the past 365 days; usual principal and subsidiary status (UPSS) relating to the status of the principal activity and subsidiary activities in the reference period of the previous 365 days; current weekly status (CWS), that is, the activity status pursued during a reference period of 7 days preceding the survey date; and the current daily status (CDS), that is, the time disposition of a person on each day of the reference week. Data in this study are from the last employment-unemployment survey of NSSO. Since 2017-18, the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) is the official source of information on employment and unemployment in India.

We dropped individuals having national industrial classification (NIC) code 1, that is, those who are agricultural workers: including cultivators and agricultural labourers. However, we included workers in allied activities such as fisheries, mining and quarrying.

The observations dropped were 143,076 individuals based on UPAS and 41,524 agricultural workers.

Employment status based on a reference period of 365 days.

This is the ratio of dependants in a household to the total number of members of the household. The dependants in a household are children below 5 years of age and those above 60 years of age and not in the workforce.

Results based on education categories are not provided for brevity but can be provided upon request. The main findings of our paper do not change qualitatively when we treat education as a categorical variable.

The MGNREGS aims to enhance the livelihood security of people in rural areas by guaranteeing 100 days of wage-employment in a financial year to a rural household whose adult members volunteer to do unskilled manual work in the vicinity.

References

Abraham, R. 2017. Informality in the Indian labour market: An analysis of forms and determinants. The Indian Journal of Labour Economics 60 (2): 191–215.

Afridi, F., T. Dinkelman, and K. Mahajan. 2016. Why are fewer married women joining the work force in India? A decomposition analysis over two decades. IZA discussion paper no. 9722.

Amaral, P., and E. Quintin. 2006. A competitive model of the informal sector. Journal of Monetary Economics 53: 1541–1553.

Azuma, Y., and H.I. Grossman. 2008. A theory of the informal sector. Economics and Politics 20 (1): 62–79.

Bairagya, I. 2012. Employment in India’s informal sector: Size, patterns, growth and determinants. Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy 17 (4): 593–615.

Bairagya, I. 2018. Why is unemployment higher among the educated? Economic and Political Weekly 53 (7): 43–51.

Banerjee, A.V., and E. Duflo. 2008. What is middle class about the middle classes around the world? Journal of Economic Perspectives 22 (2): 3–28.

Basu, A.K., N.H. Chau, and Z. Siddique. 2012. Tax evasion, minimum wage noncompliance and informality. In Informal employment in emerging and transition economies, 1–53. Bingley: Emerald Group.

Behrman, J.R., and P. Taubman. 1989. Is schooling ‘mostly in the genes’? Nature-nurture decomposition using data on relatives. Journal of Political Economy 97 (6): 1425–1446.

Binswanger-Mkhize, H.P. 2013. The stunted structural transformation of the Indian economy. Economic and Political Weekly 48 (26–27): 5–13.

Breman, J. 1996. Footloose labour: Working in India’s informal sector. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chaudhuri, T.D. 1989. A theoretical analysis of the informal sector. World Development 17 (3): 351–355.

Chen, M.A. 2001. Women and informality: A global picture, the global movement. SAIS Review 21 (1): 71–82.

Chen, M.A. 2012. The informal economy: Definitions, theories and policies. Manchester: WIEGO.

De Soto, H. 1989. The other path: The invisible revolution in the third world. New York: Harper and Row.

Demenet, A., M. Razafindrakoto, and F. Roubaud. 2016. Do informal businesses gain from registration and how? Panel data evidence from Vietnam. World Development 84: 326–341.

Fields, G.S. 1990. Labour market modelling and the urban informal sector: Theory and evidence. In The informal sector revisited, ed. D. Turnham, B. Salomé, and A. Schwarz, 49–69. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Fields, G.S. 2003. Decent work and development policies. International Labour Review 142 (2): 239–262.

Friedman, E., S. Johnson, D. Kaufmann, and P. Zoido-Lobaton. 2000. Dodging the grabbing hand: The determinants of unofficial activity in 69 countries. Journal of Public Economics 76: 459–493.

Greene, W.H. 2010. Testing hypothesis about interaction terms in non-linear models. Economic Letters 107: 291–296.

Günther, I., and A. Launov. 2012. Informal employment in developing countries: Opportunity or last resort? Journal of Development Economics 97 (1): 88–98.

Hart, K. 1973. Informal income opportunities and urban employment in Ghana. The Journal of Modern African Studies 11 (01): 61–89.

Heckman, J.J. 1976. The common structure of statistical models of truncation, sample selection and limited dependent variables and a simple estimator for such models. Annals of Economic and Social Measurement 5 (4): 475–492.

Heckman, J.J. 1979. Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica 47 (1): 153–161.

Henley, A., G.R. Arabsheibani, and F.G. Carneiro. 2009. On defining and measuring the informal sector: Evidence from Brazil. World Development 37 (5): 992–1003.

Himanshu, 2011. Employment trends in India: A re-examination. Economic and Political Weekly 46 (37): 43–59.

Huesca, L., and M. Camberos. 2010. Selection bias correction based on the multinomial logit: An application to the Mexican labour market. In 2nd Stata users group meeting Mexico, Universidad Iberoamericana Campus Mexico, April, vol. 29.

Huitfeldt, H., and J. Jütting. 2009. Informality and informal employment. In Promoting pro-poor growth: Employment, 95–108, OECD Development Centre.

Hunt, A., and E. Samman. 2016. Women’s economic empowerment: Navigating enablers and constraints. In UN High Level Panel on Women‟ s Economic Empowerment background paper. London: Overseas Development Institute.

Hussmanns, R. 2001. Informal sector and informal employment: Elements of a conceptual framework. In Fifth meeting of the expert group on informal sector statistics (Delhi Group), 19–21, New Delhi.

Hussmanns, R. 2002. A labour force survey module on informal employment (including employment in the informal sector) as a tool for enhancing the international comparability of data. In Sixth meeting of the expert group on informal sector statistics (Delhi Group), 16–18, Rio de Janeiro.

Hussmanns, R. 2004. Defining and measuring informal employment. Bureau of statistics paper. ILO, Geneva. http://www.ilo.org/public/english/bureau/stat/download/papers/meas.Pdf. Accessed 12 May 2018.

ILO. 2014. Transitioning from the informal to the formal economy. Geneva: International Labour Organization.

ILO. 2016. India labour market update. http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—asia/—ro-bangkok/—sronew_delhi/documents/publication/wcms_496510.pdf. Accessed 15 May 2018.

ILO (2018). Empowering women working in the informal economy, Issue Brief No. 4. Geneva: International Labour Organization.

Jatav, M., and S. Sen. 2013. Drivers of non-farm employment in rural India. Economic and Political Weekly 48 (26–27): 14–21.

Kanbur, R. 2009. Conceptualising informality: regulation and enforcement. IZA discussion paper no. 4186. Bonn: Institute of Labour Economics.

Kannan, K.P. 2014. Interrogating inclusive growth: Poverty and inequality in India. New Delhi: Routledge.

Kannan, K.P., and G. Raveendran. 2009. Growth sans employment: A quarter century of jobless growth in India’s organised manufacturing. Economic and Political Weekly 44 (10): 80–91.

Kucera, D., and L. Roncolato. 2008. Informal employment: Two contested policy issues. International Labour Review 147 (4): 321–348.

La Porta, R., and A. Shleifer. 2014. Informality and development. The Journal of Economic Perspectives 28 (3): 109–126.

Labour Bureau. 2017. Annual report 2017–18, Ministry of labour and employment, Government of India.

Lehmann, H. 2015. Informal employment in transition countries: Empirical evidence and research challenges. Comparative Economic Studies 57 (1): 1–30.

Loayza, N.V. 1996. The economics of the informal sector: A simple model and some empirical evidence from Latin America. In Carnegie-Rochester conference series on public policy, vol. 45, 129–162. North-Holland.

Magnac, T. 1991. Segmented or competitive labor markets. Econometrica 59 (1): 165–187.

Maiti, D., and K. Sen. 2010. The informal sector in India: a means of exploitation or accumulation? Journal of South Asian Development 5 (1): 1–13.

Maloney, W.F. 1999. Does informality imply segmentation in urban labor markets? Evidence from sectoral transitions in Mexico. The World Bank Economic Review 13 (2): 275–302.

Maloney, W.F. 2004. Informality revisited. World Development 32 (7): 1159–1178.

Mazumdar, I., and N. Neetha. 2011. Gender dimensions: Employment trends in India, 1993–94 to 2009–10. Economics and Political Weekly 46 (43): 118–126.

Mehrotra, S., A. Kalaiyarasan, N. Kumra, and K.R. Raman. 2015. Vocational training in India and the duality principle: A case for evidence-based reform. Prospects 45 (2): 259–273.

Mehrotra, S., and J.K. Parida. 2017. Why is the labour force participation of women declining in India? World Development 98: 360–380.

MSDE. 2016. Report of the committee for rationalization and optimization of the functioning of the sector skill councils. New Delhi: Ministry of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship.

Narayanan, A. 2015. Informal employment in India: Voluntary choice or a result of labor market segmentation? Indian Journal of Labour Economics 58 (1): 119–167.

NCEUS. 2008. Report on definitional and statistical issues relating to informal economy. New Delhi: National Commission for Enterprises in the Unorganised Sector.

Papola, T.S. 1981. Urban informal sector in a developing economy. New Delhi: Vikas.

Perry, G.E., W.F. Maloney, O.S. Arias, P. Fajnzylber, A.D. Mason, and J. Saavedra-Chanduvi. 2007. Informality: exit and exclusion. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Pradhan, M., and A. Van Soest. 1995. Formal and informal sector employment in urban areas of Bolivia. Labour Economics 2 (3): 275–297.

Radchenko, N. 2014. Heterogeneity in informal salaried employment: Evidence from the Egyptian labor market survey. World Development 62: 169–188.

Raj, R.S., and K. Sen. 2015. Finance constraints and firm transition in the informal sector: Evidence from Indian manufacturing. Oxford Development Studies 43 (1): 123–143.

Sahoo, B.K., and B.J. Neog. 2017. Heterogeneity and participation in informal employment among non-cultivator workers in India. International Review of Applied Economics 31 (4): 437–467.

Sapkal, R.S., and K.S. Sundar. 2017. Determinants of precarious employment in India: An empirical analysis. In Precarious work, 335–361. Bingley: Emerald.

Schneider, F. 2012. The shadow economy and work in the shadow: What do we (not) know? IZA discussion paper no. 6423. Bonn: Institute of Labour Studies.

Standing, G. 1999. Global labour flexibility: Seeking distributive justice. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Stark, O. 1982. On modelling the informal sector. World Development 10 (5): 413–416.

Thomas, J.J. 2014. The demographic challenge and employment growth in India. Economic and Political Weekly 49 (6): 15–17.

Woodruff, C., and D. McKenzie. 2006. Do entry costs provide an empirical basis for poverty traps? Evidence from Mexican microenterprises. Economic Development and Cultural Change 55: 3–42.

World Bank. 2018. South Asia economic focus: Jobless growth. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sheikh, R.A., Gaurav, S. Informal Work in India: A Tale of Two Definitions. Eur J Dev Res 32, 1105–1127 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-020-00258-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-020-00258-z