Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to examine the hypothesis that increased participation in global value chains (GVCs), such as assembly of imported parts for exports, leads to higher economic growth. The focus is particularly on the extent to which this holds for low-income countries, and the role that capability-building, i.e. development of the national innovation system, plays in the possibility of benefitting from GVCs. The analysis is based on evidence from 125 countries over the period 1997–2013. To analyse the issue, a comprehensive framework that allows for inclusion of a range of relevant factors, including GVC participation (measured by the foreign value added embodied in a country’s exports), is applied. The results suggest that countries that increase GVC participation do not grow faster than other countries, when other relevant factors are controlled for. Small countries, and countries with low capabilities, appear to be particularly disadvantaged.

Le but de cet article est d’examiner l’hypothèse selon laquelle une participation accrue aux chaînes de valeur mondiales (CVM), telle que l’assemblage de parties importées dans le but de les exporter, conduit à une croissance économique plus élevée. L’accent est mis surtout sur la pertinence de cet hypothèse pour les pays en développement. L’analyse est fondée sur des données probantes provenant de 125 pays, dont de nombreux pays à faible revenu, sur la période 1997–2013. Pour analyser la question, un cadre global qui permet d’inclure une série de facteurs pertinents, y compris la valeur ajoutée étrangère dans les exportations d’un pays (importations CVM), est appliqué. Les résultats présentés dans l’article suggèrent que les pays qui augmentent les importations de la chaîne de valeur mondiale ne connaissent pas une croissance plus rapide que d’autres pays, lorsque d’autres facteurs sont contrôlés. Les petits pays, et les pays à faible capacité, semblent particulièrement désavantagés.

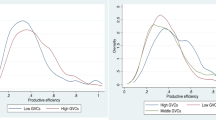

Note: The baseline is the estimated beta coefficient of Δ GVC imports. Interaction is the estimated coefficient of an interaction term between Δ GVC imports and a dummy variable for countries with capabilities exceeding a certain threshold level. Total is the sum of the baseline coefficient and the interaction term. All other variables remain the same as in the third column of Table 1. Smoothed values (the lines) are derived from kernel-weighted local polynomial smoothing (using Epanechnikov kernel function).

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Abramovitz, M. (1986) Catching up, forging ahead, and falling behind. Journal of Economic History 46: 386–406.

Ali-Yrkkö, J., Rouvinen, P., Seppälä, T. and Ylä-Anttila, P. (2011) Who captures value in global supply chains? Case Nokia N95 smartphone. Journal of Industry, Competition and Trade 11(3): 263–278.

Altenburg, T. (2006) Governance patterns in value chains and their development impact. European Journal of Development Research 18(4): 498–521.

Barro, R.J. (1991) Economic growth in a cross section of countries. Quarterly Journal of Economics 106: 407–443.

Bell, M. and Marin, A. (2004) Where do FDI-related technology spillovers come from in emerging economies? An exploration in Argentina in the 1990s. European Journal of Development Research 16: 653–686.

Borensztein, E., De Gregorio, J. and Lee, J.-W. (1998) How does foreign direct investment affect economic growth? Journal of International Economics 45: 115–135.

Castellacci, F. and Natera, J.M. (2011) A new panel dataset for cross-country analyses of national systems, growth and development (CANA). Innovation and Development 1: 205–226.

Castellani, D. and Zanfei, A. (2006) Multinational Firms, Innovation and Productivity. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Chang, H.-J. (2002) Kicking Away the Ladder—Development Strategy in Historical Perspective. London: Anthem.

Cirera, X. and Maloney, W.F. (2017) The Innovation Paradox: Developing Country Capabilities and the Unrealized Promise of Technological Catch Up. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Cohen, W.M. and Levinthal, D.A. (1990) Absorptive Capacity: A New Perspective on Learning and Innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly 35(1): 128–152.

Cornwall, J. (1976) Diffusion, Convergence and Kaldor’s Law. Economic Journal 85: 307–314.

Criscuolo, P. and Narula, R. (2008) A novel approach to national technological accumulation and absorptive capacity: aggregating Cohen and Levinthal. European Journal of Development Research 20(1): 56–73.

Del Prete, D., Giovannetti, G. and Marvasi, E. (2017) Global value chains: New evidence for North Africa, International Economics. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inteco.2017.03.002.

Eora. (2016) The Eora multi-region input-output table (MRIO) database. http://www.worldmrio.com, accessed 1 June 2017.

Ernst, D. and Kim, L. (2002) Global production networks, knowledge diffusion, and local capability formation. Research Policy 31(8): 1417–1429.

Fagerberg, J. and Godinho, M.M. (2004) Innovation and Catching-up. In: Fagerberg, J., Mowery, D. and Nelson, R. (eds.) The Oxford Handbook of Innovation. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 514–542.

Fagerberg, J. and Srholec, M. (2008) National innovation systems, capabilities and economic development. Research Policy 37: 1417–1435.

Fagerberg, J. and Srholec, M. (2009) Innovation systems, technology and development: Unpacking the relationship(s). In: Lundvall, B.-A., Joseph, K.J., Chaminade, C. and Vang, J. (eds.) Handbook of Innovation Systems and Developing Countries: Building Domestic Capabilities in a Global Context. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, pp. 83–115.

Fagerberg, J. and Srholec, M. (2017) Capabilities, economic development, sustainability. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 41: 905–926.

Fagerberg, J., Srholec, M. and Verspagen, B. (2010) Innovation and economic development. In: Hall, B. and Rosenberg, N. (eds.) Handbook of the Economics of Innovation, Vol. II. North Holland, The Netherlands: Elsevier, pp. 833–872.

Filippetti, A., Frenz, M. and Ietto-Gillies, G. (2016) The impact of internationalization on innovation at countries’ level: The role of absorptive capacity. Cambridge Journal of Economics 41(2): 413–439.

Fitter, R. and Kaplinsky, R. (2001) Who gains from product rents as the coffee market becomes more differentiated? A value-chain analysis. IDS Bulletin 32(3): 69–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1759-5436.2001.mp32003008.x.

Foster‐McGregor, N., Kaulich, F. and Stehrer, R. (2015) Global value chains in Africa. UNU-MERIT Working Paper Series #2015-024.

Fu, X., Pietrobelli, C. and Soete, L. (2011) The role of foreign technology and indigenous innovation in the emerging economies: Technological change and catching-up. World Development 39: 1204–1212.

Gallup, J.L., Sachs, J.D. and Mellinger, A. (1999) Geography and economic development (CID Working Paper No. 1). Cambridge: Harvard University.

Gereffi, G. (2014) Global value chains in a post-Washington Consensus world. Review of International Political Economy 21: 9–37.

Gereffi, G. (1999) International trade and industrial upgrading in the apparel commodity chain. Journal of International Economics 48: 37–70.

Gereffi, G. and Fernandez-Stark. K. (2011) Global value chain analysis: A primer. Center on Globalization, Governance & Competitiveness (CGGC), Duke University.

Gereffi, G. and Korzeniewicz, M. (1994) Commodity Chains and Global Capitalism. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger.

Gereffi, G. and Lee, J. (2012). Why the world suddenly cares about global supply chains. Journal of Supply Chain Management 48(3): 24–32.

Gereffi, G., Humphrey, G.J. and Sturgeon, T. (2005) The governance of global value chains. Review of International Political Economy 12: 78–104.

Gerschenkron, A. (1962) Economic Backwardness in Historical Perspective. Cambridge: Belknap.

Giroud, A. and Mirza, H. (2015) Refining FDI motivations by integrating global value chains’ considerations. Multinational Business Review 23(1): 67–76.

Giuliani, E., Pietrobelli, C. and Rabellotti, R. (2005) Upgrading in global value chains: Lessons from Latin American clusters. World Development 33(4): 549–573.

Gomulka, S. (1971) Inventive Activity, Diffusion and the Stages of Economic Growth. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press.

Görg, H. and D. Greenaway (2004) Much ado about nothing? Do domestic firms really benefit from foreign direct investment? The World Bank Research Observer 19: 171–197.

Humphrey, J, and Schmitz. H. (2002) How does insertion in global value chains affect upgrading in industrial clusters? Regional Studies 36: 1017–1027.

Humphrey, J. and Schmitz, H. (2000) Governance and upgrading: Linking industrial cluster and global value chain research. IDS Working Paper, No. 120, Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex, Brighton.

IMF. (1997) World Economic Outlook, October 1997. International Monetary Fund, Statistical Appendix, https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/weo1097/weocon97.htm, accessed 1 June 2017.

IRC Trade Task Force. (2016) Understanding the weakness in global trade. What is the new normal? European Central Bank, Occasional Paper Series No 178/September 2016, https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpops/ecbop178.en.pdf, accessed 25 September 2017.

ISO. (2014) ISO Survey 2014. International Organization for Standardization, https://www.iso.org/the-iso-survey.html, accessed 1 June 2017.

Kaplinsky, R. and Morris, M. (2015) Thinning and thickening: productive sector policies in the era of global value chains. European Journal of Development Research 28(4): 625–645.

Keller, W. (2010) International trade, foreign direct investment, and technology spillovers. In: Hall, B. and Rosenberg, N. (eds.) Handbook of the Economics of Innovation, Vol. II. North Holland, The Netherlands: Elsevier, pp. 793–829

Kim, L. (1997) Imitation to Innovation: The Dynamics of Korea’s Technological Learning. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Kiszewski, A., Mellinger, A., Spielman, A. and Malaney, P. (2004) A global index of the stability of malaria transmission. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 70: 486–498.

Koopman, R., Powers, W., Wang, Z. and Wei, S.-J. (2010) Give credit where credit is due: Tracing value added in global production chains. NBER Working Paper No. 16426. Cambridge, MA. https://doi.org/10.3386/w16426, Accessed 17 April 2018.

Koopman, R., Wang, Z. and Wei, S.-J. (2014) Tracing value-added and double counting in gross exports. American Economic Review 104(2): 459–494.

Kummritz, V. (2015) Global value chains: Benefitting the domestic economy? CTEI Working Papers, CTEI-2014-05, http://graduateinstitute.ch/files/live/sites/iheid/files/sites/ctei/shared/CTEI/working_papers/CTEI-2014-05-Kummritz.pdf, accessed 17 April 2018.

Kummritz, V. and Quast, B. (2016) Global value chains in low and middle income countries. CTEI Working Papers, CTEI No 2016-10, http://graduateinstitute.ch/files/live/sites/iheid/files/sites/ctei/shared/CTEI/working_papers/CTEI-2016-10%20Kummritz%20Quast_GVCs.pdf, accessed 17 April 2018.

Lall, S. (1992) Technological capabilities and industrialization. World Development 20(2): 165–186.

Lee, K. (2013) Schumpeterian Analysis of Economic Catch-up. Knowledge, Path-Creation, and the Middle-Income Trap. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Li, G. (1985) Robust regression. In: Hoaglin, D.C., Mosteller, F. and Tukey, J.W. (eds.) Exploring Data Tables, Trends, and Shapes. New York: Wiley, pp. 281–340.

Linden, G., Kraemer, K.L. and Dedrick, J. (2009) Who captures value in a global innovation network? The case of apple’s iPod. Communications of the ACM 52(3): 140–144.

Lundvall, B.-Å. (1992) National Innovation Systems: Towards a Theory of Innovation and Interactive Learning. London: Pinter.

Lundvall, B.-A., Joseph, K.J., Chaminade, C. and Vang, J. (2009) Handbook of Innovation Systems and Developing Countries. Building Domestic Capabilities in a Global Context. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Morris, M., Kaplinsky, R. and Kaplan, D. (2012) One thing leads to another: Commodities, linkages and industrial development. Resources Policy 37(4): 408–416.

Narula, R. (2014) Foreign direct investment as a driver of industrial development: Why is there so little evidence? In: Van Tulder, R., Verbeke, A. and Strange, R. (eds.) Progress in International Business Research, Vol. 8. Bingley: Emerald Group, pp. 45–67.

Narula, R. (2018) Multinational firms and the extractive sectors in the 21st century: Can they drive development? Journal of World Business 53(1): 85–91.

Narula, R. and Dunning, J. H. (2010) Multinational enterprises, development and globalisation: Some clarifications and a research agenda. Oxford Development Studies 38: 263–287.

Nelson, R. (1993) National Innovation Systems: A Comparative Analysis. New York: Oxford University Press.

Nomaler, Ö. and Verspagen, B. (2014) Analysing global value chains using input-output economics: Proceed with care. UNU-MERIT Working Paper No. 2014-070, UNUMERIT, Maastricht.

OECD. (2016) OECD.Stat. Paris: OECD.

Pietrobelli, C. and Staritz. C. (2018) Upgrading, interactive learning, and innovation systems in value chain interventions. European Journal of Development Research. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-017-0112-5.

Ponte, S. and Ewert, J. (2009) Which way is ‘up’ in upgrading: Trajectories of change in the value chain for South African wine. World Development 37(10): 1637–1650.

PRS Group (2014) International Country Risk Guide: Table 3B: Political Risk Points by Component. Syracuse, NY: PRS Group.

Rodrik, D. (1994) King Kong meets godzilla: The World Bank and the East Asian miracle. In: Fishlow, A., Gwin, C., Haggard, S. and Rodrik, D. (eds.) Miracle or Design? Lessons from the East Asian Experience, Vol. 11. Washington, DC: Overseas Development Council, pp. 13–38.

Rojec, M. and Knell, M. (2017) Why is there a lack of evidence on knowledge spillovers from foreign direct investment? Journal of Economic Surveys. https://doi.org/10.1111/joes.12207.

Saxenian, A. (2006) The New Argonauts: Regional Advantage in the Global Economy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Schmitz, H. (1995) Small shoemakers and Fordist giants: Tale of a supercluster. World Development 23: 9–28.

Schmitz, H. (1999) Global competition and local cooperation: success and failure in the Sinos Valley, Brazil. World Development 27(9): 1627–1650.

SCImago. (2016) SCImago Journal & Country Rank. Scopus database, Elsevier, http://www.scimagojr.com/countryrank.php, accessed 1 June 2017.

Stata. (2005) Stata Data Management, Reference Manual, Release 9. College Station: Stata Press.

Stata. (2017) Stata Base Reference Manual, Release 15. College Station: Stata Press.

Sturgeon, T. (2001) How do we define value chains and production networks? IDS Bulletin 32: 9–18.

Sturgeon, T.J. (2002) Modular production networks: A new American model of industrial organization. Industrial and Corporate Change 11(3): 451–496.

Tajoli, L. and Felice, G. (2018) Global value chains participation and knowledge spillovers in developed and developing countries: An empirical investigation. European Journal of Development Research. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-017-0127-y.

Timmer, M.P., Dietzenbacher, E., Los, B., Stehrer, R. and de Vries, G.J. (2015) An illustrated user guide to the world input–output database: The case of global automotive production. Review of International Economics 23: 575–605.

Timmer, M., Erumban, A., Los, B., Stehrer, R. and de Vries, G. (2014) Slicing up global value chains. Journal of Economic Perspectives 28(2): 99–118.

UN. (2016) UN comtrade database. United Nations, New York, http://comtrade.un.org/data, accessed 1 June 2017.

UNCTAD. (2016) UNCTAD statistics on-line. Geneva: UNCTAD, http://unctad.org/en/Pages/Statistics.aspx, accessed 1 June 2017.

UNCTAD. (2013) Global value chains and development: Investment and value added trade in the global economy. Geneva: UNCTAD, http://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/diae2013d1_en.pdf, accessed 1 June 2017.

UNCTAD/Eora. (2016) The trade in value added database (TiVA). http://www.worldmrio.com, accessed 1 June 2017.

UNDP. (2016) Human development report 2015. United Nations Development Programme. New York, http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/2015_human_development_report.pdf, accessed 1 June 2017.

UNESCO. (2016) On-line Data Centre. Geneva: UNESCO Institute for Statistics, http://www.uis.unesco.org/Pages/default.aspx, accessed 1 June 2017.

USPTO. (2016) Extended year set - patents by country, state, and year utility patents (December 2015). U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, http://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/ac/ido/oeip/taf/cst_utlh.htm, accessed 1 June 2017.

Wagner, C.S. and Leydesdorff, L. (2005) Network structure, self-organization, and the growth of international collaboration in science. Research Policy 34: 1608–1618.

WIPO. (2016) WIPO statistics database. World Intellectual Property Organization, http://www.wipo.int/ipstats/en/, accessed 1 June 2017.

World Bank. (2015) How does the World Bank classify countries? World Bank, https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/378834-how-does-the-world-bank-classify-countries, accessed 1 June 2017.

World Bank. (2016) World development indicators 2015. World Bank, Last Updated on 17 February 2016

Xu, B. (2000) Multinational enterprises, technology diffusion, and host country productivity growth. Journal of Development Economics 62(2): 477–493.

Acknowledgements

Financial support from the VINNOVA Core Funding of Centers for Innovation Systems Research project 2010-01370 on “Transformation and Growth in Innovation Systems: Innovation Policy for Global Competitiveness of SMEs and R&I Milieus” and the Czech Science Foundation (GAČR) project 17-09628S on “Innovation activities in global production networks: Evidence from Czech business enterprises” is gratefully acknowledged. Earlier versions of the paper were presented at the 2016 OBEL Symposium on Innovation Systems, Globalization and Development, May 10–12, 2016, Aalborg, Denmark, the 14th Globelics International Conference, October 12–14, 2016, Bandung, Indonesia and the workshop on “Innovation Systems in the era of Global Value Chains”, April 24–25, 2017, Copenhagen, Denmark. We thank participants at these events, especially John Humphrey, Ned Lorenz and Bart Verspagen, and reviewers and editors of the journal for useful comments and suggestions. All usual caveats apply.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix A1: Definitions and Sources of the Variables

Indicator and definition | Scaling | Source | Estimated observations |

|---|---|---|---|

GDP per capita Gross domestic product converted to constant 2011 international dollars using purchasing power parity rates | USD per capita | World Bank (2016) | 0 |

Scientific and engineering articles Counts of citable documents recorded in SCImago Journal and Country Rank (based on information contained in the Scopus database) | Per mil. people | SCImago (2016) | 0 |

USPTO patent applications Counts of applications for utility patents filed in the US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) classified by country of residence of the first named inventor | Per mil. people | USPTO (2016) | 0 |

R&D expenditures Intramural expenditure on research and experimental development (R&D) performed on the national territory | % of GDP | UNESCO (2016), OECD (2016), Castellacci and Natera (2011) and national sources | 39 |

Trademark applications Counts of applications for registration of trademarks filed by residents directly and via the Madrid system | Per mil. people | WIPO (2016) | 43 |

ISO 9001 certifications Counts of ISO 9001 management system standard certifications | Per mil. people | ISO (2014) | 0 |

Internet users Internet users are individuals who have used the Internet (from any location) in the last 12 months | Per 100 people | World Bank (2016) | 0 |

Mean years of schooling Average number of years of education received by people aged 25 years and older, converted from education attainment levels using official durations of each level | Years | UNDP (2016) | 0 |

Adult literacy People aged 15 years and over who can read, understand and write a short, simple statement on their everyday life | % of adult population | 2 | |

Bureaucracy quality An assessment of the institutional strength and quality of the bureaucracy, which represents a shock absorber that tends to limit revisions of policy when governments change | Index | PRS Group (2014) | 10 |

GVC imports Imported inputs (produced in other countries) accounted in the gross exports of a country derived from input–output tables | % of GDP | UNCTAD/Eora (2016) | 0 |

Capital goods imports Imports of capital goods (BEC, rev. 3 categories 41, 51 and 52) derived from trade in goods statistics | % of GDP | UN (2016) | 7 |

FDI inward The value of capital and reserves (including retained profits) attributable to foreign parent enterprises with lasting management interest, plus the net indebtedness of foreign affiliates to the parent enterprises | % of GDP | UNCTAD (2016) | 0 |

Outbound mobility of tertiary students Gross outbound tertiary enrolment ratio given by the number of tertiary students from a given country studying in North America and Western Europe expressed as the percentage of the population of tertiary age in that country | Gross enrolment in % | UNCTAD (2016) | 8 |

Size (population) All residents regardless of legal status or citizenship (except for refugees not permanently settled in the country of asylum) who are generally considered part of the population of their country of origin | People | World Bank (2016) | 0 |

Agriculture Agriculture corresponds to ISIC divisions 1-5 and includes forestry, hunting and fishing, as well as cultivation of crops and livestock production | % of GDP | World Bank (2016) | 0 |

Natural resources rents The sum of oil rents, natural gas rents, coal rents (hard and soft), mineral rents and forest rents | % of GDP | World Bank (2016) | 0 |

Tropics Proportion of land area in Köppen–Geiger tropics | Share | Gallup et al (1999) | 0 |

Malaria ecology Stability of malaria transmission given by biologic characteristics of vector mosquitoes | Index | Kiszewski et al (2004) | 0 |

Appendix A2: Capabilities: Results of the Factor Analysis

Factor loadings | |

|---|---|

Scientific and engineering articles (per capita) | 0.94 |

USPTO patent applications (per capita) | 0.87 |

R&D expenditures (% of GDP) | 0.79 |

Trademark applications (per capita) | 0.76 |

ISO 9001 certifications (per capita) | 0.91 |

Internet users (per capita) | 0.70 |

Years of schooling (years) | 0.80 |

Adult literacy (% of adult population) | 0.68 |

Bureaucracy quality (index) | 0.76 |

Appendix A3: Descriptive Statistics

Mean | SD | Min. | Max. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Δ GDP per capita | 0.024 | 0.020 | −0.036 | 0.097 |

GDP per capita | 9.071 | 1.243 | 6.195 | 11.609 |

Capabilities | −0.286 | 0.950 | −2.222 | 1.520 |

Δ capabilities | 0.036 | 0.014 | 0.009 | 0.081 |

GVC imports | 1.657 | 0.872 | 0.284 | 3.967 |

Δ GVC imports | 0.024 | 0.023 | −0.039 | 0.089 |

Capital goods imports | 1.955 | 0.457 | 0.701 | 3.280 |

Δ capital goods imports | 0.003 | 0.025 | −0.072 | 0.076 |

FDI inward | 2.665 | 0.834 | 0.486 | 5.128 |

Δ FDI inward | 0.061 | 0.054 | −0.069 | 0.272 |

Outbound mobility of tertiary students | 0.542 | 0.594 | 0.019 | 3.294 |

Δ outbound mobility of tertiary students | 0.010 | 0.018 | −0.020 | 0.088 |

Size (population) | 16.217 | 1.559 | 12.510 | 20.930 |

Agriculture | 2.318 | 0.975 | 0.086 | 4.073 |

Natural resources rents | 1.506 | 1.129 | 0.000 | 3.807 |

Tropics | 1.566 | 2.020 | 0.000 | 4.615 |

Malaria | 0.684 | 1.016 | 0.000 | 3.483 |

Appendix A4: List of Countries (Alphabetical)

Albania | Croatia | Iran | Morocco | Slovenia |

Algeria | Cyprus | Ireland | Mozambique | South Africa |

Argentina | Czech Rep. | Israel | Namibia | Spain |

Armenia | Denmark | Italy | Netherlands | Sri Lanka |

Australia | Dominican Rep. | Jamaica | New Zealand | Sweden |

Austria | Ecuador | Japan | Nicaragua | Switzerland |

Azerbaijan | Egypt | Jordan | Niger | Taiwan |

Bahrain | El Salvador | Kazakhstan | Nigeria | Tajikistan |

Bangladesh | Estonia | Kenya | Norway | Tanzania |

Belarus | Ethiopia | Korea | Oman | Thailand |

Belgium | Finland | Kuwait | Pakistan | Togo |

Bolivia | France | Kyrgyzstan | Panama | Trinidad and Tobago |

Botswana | Gabon | Latvia | Papua New Guinea | Tunisia |

Brazil | Georgia | Lebanon | Paraguay | Turkey |

Brunei Darussalam | Germany | Lithuania | Peru | Uganda |

Bulgaria | Ghana | Luxembourg | Philippines | Ukraine |

Burkina Faso | Greece | Macedonia | Poland | United Arab Emirates |

Cambodia | Guatemala | Madagascar | Portugal | United Kingdom |

Cameroon | Guinea | Malawi | Qatar | United States |

Canada | Honduras | Malaysia | Romania | Uruguay |

Chile | Hong Kong | Mali | Russia | Venezuela |

China | Hungary | Malta | Saudi Arabia | Vietnam |

Colombia | Iceland | Mexico | Senegal | Yemen |

Costa Rica | India | Moldova | Singapore | Zambia |

Côte d’Ivoire | Indonesia | Mongolia | Slovakia | Zimbabwe |

Appendix A5: Correlation Table

Δ GDP per capita | GDP per capita | Capabilities | Δ capabilities | GVC imports | Δ GVC imports | Capital goods imports | Δ capital goods imports | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Δ GDP per capita | 1.00 | |||||||

GDP per capita | −0.37 | 1.00 | ||||||

Capabilities | −0.16 | 0.83 | 1.00 | |||||

Δ capabilities | 0.34 | 0.05 | −0.15 | 1.00 | ||||

GVC imports | 0.06 | 0.50 | 0.63 | 0.08 | 1.00 | |||

Δ GVC imports | −0.13 | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.00 | −0.02 | 1.00 | ||

Capital goods imports | −0.02 | 0.28 | 0.26 | 0.00 | 0.63 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

Δ capital goods imports | 0.08 | −0.36 | −0.28 | −0.03 | −0.27 | 0.30 | −0.42 | 1.00 |

FDI inward | 0.05 | 0.16 | 0.16 | −0.09 | 0.39 | −0.04 | 0.47 | −0.20 |

Δ FDI inward | −0.02 | 0.04 | 0.10 | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.09 |

Outbound mobility of tertiary students | −0.28 | 0.64 | 0.56 | 0.03 | 0.43 | 0.13 | 0.41 | −0.45 |

Δ outbound mobility of tertiary students | 0.36 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.40 | 0.19 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.08 |

Size (population) | 0.18 | −0.25 | −0.11 | 0.06 | −0.25 | −0.08 | −0.59 | 0.21 |

Agriculture | 0.36 | −0.92 | −0.79 | 0.04 | −0.49 | −0.08 | −0.30 | 0.31 |

Natural resources rents | −0.06 | −0.27 | −0.57 | 0.05 | −0.42 | −0.34 | −0.11 | 0.09 |

Tropics | −0.01 | −0.42 | −0.48 | −0.11 | −0.26 | −0.15 | 0.00 | −0.09 |

Malaria | −0.13 | −0.59 | −0.61 | −0.26 | −0.37 | −0.05 | −0.05 | 0.16 |

FDI inward | Δ FDI inward | Outbound mobility of tertiary students | Δ outbound mobility of tertiary students | Size (population) | Agriculture | Natural resources rents | Tropics | Malaria | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Δ GDP per capita | |||||||||

GDP per capita | |||||||||

Capabilities | |||||||||

Δ capabilities | |||||||||

GVC imports | |||||||||

Δ GVC imports | |||||||||

Capital goods imports | |||||||||

Δ capital goods imports | |||||||||

FDI inward | 1.00 | ||||||||

Δ FDI inward | −0.47 | 1.00 | |||||||

Outbound mobility of tertiary students | 0.22 | 0.22 | 1.00 | ||||||

Δ outbound mobility of tertiary students | −0.04 | 0.24 | 0.02 | 1.00 | |||||

Size (population) | −0.24 | −0.25 | −0.52 | −0.17 | 1.00 | ||||

Agriculture | −0.23 | −0.03 | −0.60 | 0.03 | 0.22 | 1.00 | |||

Natural resources rents | −0.03 | −0.28 | −0.31 | −0.07 | 0.01 | 0.30 | 1.00 | ||

Tropics | 0.02 | −0.16 | −0.29 | −0.21 | 0.14 | 0.38 | 0.32 | 1.00 | |

Malaria | 0.05 | −0.14 | −0.28 | −0.22 | 0.08 | 0.46 | 0.39 | 0.59 | 1.00 |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fagerberg, J., Lundvall, BÅ. & Srholec, M. Global Value Chains, National Innovation Systems and Economic Development. Eur J Dev Res 30, 533–556 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-018-0147-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-018-0147-2