Abstract

Existing studies suggest that what people do and do not think of as being ‘politics’, varies a lot. Some citizens embrace narrow understandings, regarding only few issues as ‘political’. While others hold broad conceptions. What remains unclear is to what extent citizens agree on the contents, i.e., which topics are ‘political’. Using representative survey data from the U.S. (N = 1000), this article illustrates the overlaps and differences in conceptions of politics that different groups of citizens hold. Specifically, the results of a cluster analysis reveal five groups. The citizens within each group share similar conceptions of politics, while across groups conceptions differ. We find one group considering everything as political, one not regarding anything as such, and a third one identifying only tax-cuts as ‘political’. In between these extremes, two groups identify politics in terms of rather demarcated spheres of issues: domestic, or cross-border/global issues. Further analyses point to important differences in the groups’ socio-demographic profiles, political interest, and political behaviors. This shows, in their minds, people draw boundaries around politics in quite varied, yet principled, ways. This comes with a meaningful diversity in citizens’ connection to the political world around them, and with important implications for their roles within it.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In their path-breaking book ‘Culture Theory’ (1990), Thompson, Ellis and Wildavsky establish the idea that the concept of politics is socially negotiated among the members of a society. According to this view, what is considered as the ‘stuff’ of politics in a society is contested, under constant revision, and culturally biased. Besides, the authors emphasize the importance of conceptions of politics at the individual level. What they suggest is that citizens’ (own) conceptions of politics, understood as their cognitive orientations that capture what is and what is not considered as ‘political’, are related to other critical aspects of democratic citizenship, like their participation in politics. In a similar vein, other cultural theorists have pointed out that how people conceptualize and perceive things both influences and gives meaning to their actions (Scruton 2002).

Delving deeper into the matter, a newer line of research focuses on exploring people’s conceptions of politics empirically. Analogous to what Thompson et al. (1990) theorize for the societal level, these studies show that it is hard to find a shared understanding among citizens. In fact, the results rather suggest that the extent to which individuals consider ideas, objects, and events as ‘political’ varies considerably. In short, individuals draw the boundary between politics and non-politics differently: Some citizens embrace narrow understandings, regarding only few issues as political. While others hold broad conceptions, considering all sorts of objects, events, and ideas as political (e.g., Morey and Eveland 2016; Fitzgerald 2013; Görtz and Dahl 2020).

These insights give an idea about the one-dimensional ‘geometry’ of conceptions of politics. Yet, valuable as these insights are, significantly less is known empirically about the content of those narrow or broad conceptions. Put simply, which ideas, events, and objects are considered as political, or not, by these different groups of citizens? Also unclear remains how these varying contents of conceptions of politics are related to other critical aspects of democratic citizenship, like the political behavior and social background of the individuals. This study aims to close this gap by moving beyond the present ‘geometrical’ insights. Specifically, we analyze if not only the breadth of individuals’ conceptions of what is political varies systematically, but also the kinds of topics which they consider as political.

We perform the to our knowledge first exploration of overlaps and differences in citizen’s substantial conceptions of politics. The principal research question is: Can we discern concrete patterns of themes, which (groups of) citizens conceptualize as political, and which they do not? Furthermore, with the discussions from cultural theory in mind that point to a link between conceptions of politics and individuals’ social background and their political partaking, we ask: In what ways, if any, are groups of citizens with different conceptions of politics similar or distinct from each other when it comes to their socio-demographic backgrounds and engagement with politics?

With this exploration, the study contributes an improved, citizen-focused understanding of the definition of politics, which can essentially inform measurements and operationalizations of the concept used in research (Doorenspleet 2015). Also, it can thereby help drawing the right conclusions from research material like citizen surveys; for example, it can help understand better why certain people or groups of people do or do not get involved politically with certain matters.

To answer our research questions, we draw on data from a representative survey conducted in the U.S. in 2010 (N = 1000). Given the exploratory nature of the study, we apply cluster analysis on responses to ‘what is political’, and group mean comparisons combined with multinomial logistic regression to understand differences in thematic compositions and groups. The paper starts with a brief review of existing research on the concept and conceptualization of politics, and from this derives its main theoretical argument. The second part of the paper turns to the method and data employed and presents the results. We see clear differences in the number and composition of topics that citizens regard as ‘political’, and which not. Some groups of citizens seem to identify nothing as political, others everything. But we also identify groups with quite differentiated, demarcated conceptualizations. Moreover, conceptions vary systematically in relation to citizens’ socio-demographic backgrounds and engagement with politics. Thus, how citizens conceptualize politics varies tremendously, and these differences appear related to where they come from socially, and to how they take part in politics.

Concepts of politics and their social backdrop

The central concept of political science is that of politics. How it is understood and conceptualized essentially guides and informs any kind of research in the discipline. Given this importance, not surprisingly though the conceptual debate is vibrant, and a common definition is far from settled (e.g., Leftwich 2008; Bartolini 2018; Palonen 2003).

Yet, to differentiate politics from other spheres (e.g., the economy, sports, family) scholars studying mass opinion and political culture tend to focus on citizens’ orientations toward specific actors of the political system (e.g., Almond and Verba 1963; Norris 2011; Easton 1975). By examining citizens’ attitudes and values regarding traditional political institutions and actors, like political parties and politicians, the research shows clearly that people, both within and across countries, tend to assess and engage with their (democratic) society very differently (e.g., Ferrín and Kriesi 2016; Putnam 2000; Kavanagh 1989). However, what these studies seems to unite is that they—implicitly or explicitly—use the term ‘political’ in a way that seems to assume that there is a general understanding of what counts as ‘political’ (Thompson et al. 1990). In other words, the authors build on an assumption that citizens on average share similar understanding of what politics is.

However, recent studies challenge this position. They suggest that the extent to which people perceive the issues and phenomena they encounter as ‘political’ or not varies considerably. Referring to conceptions of politics as individuals’ cognitive orientations of what constitutes politics (i.e., what does and what does not count as politics; e.g., Morey and Eveland 2016; Fitzgerald 2013; Görtz and Dahl 2020),Footnote 1 this ‘conceptual-breadth literature’ empirically demonstrates that some citizens label as ‘politics’ an extensive set of issues and various sorts of events, objects, and ideas. Other citizens, in turn, seem to hold a narrow conceptualization, perceiving little or even barely anything as ‘political’ (e.g., Manning 2010; Mathé 2017; O’Toole 2003).

Reporting on young citizens’ self-definitions of politics in Britain, Henn et al. (2002, 2005) for example conclude that the youth rendered few topics. Moreover, their content appeared to be narrow, corresponding to formal politics, like ‘the government’, ‘politicians’, and ‘elections’. Nonetheless, studying conceptions of politics among German citizens, Podschuweit and Jacobs (2017) reveal a larger dispersion in breadth. While most respondents (surprisingly not all) agreed that topics referring to ‘conflicts in the coalitions’ (87%) were about politics, also slightly over 60 percent identified topics related to physical infrastructure as political.Footnote 2

Comparing U.S. and Canadian citizens’ interpretations of the term, Fitzgerald (2013) asks survey respondents to categorize 33 topics according to whether they considered them to be political or not. While the average respondent categorized slightly over 14 topics as political, there showed to be considerable variation among the individuals. A few selected only one topic, some several, and others identified all 33 topics to be associated with politics. Morey and Eveland Jr. (2016) and Görtz and Dahl (2020) report similar results. What this ‘conceptual-breadth literature’ describes is that, simply put, citizens tend to draw the boundary between politics and non-politics differently, and that the meaning of politics ranges from narrow to wide.

This begs the question to what extent the contents of the different conceptualizations overlap among those with similarly narrow or wide perceptions of politics. As social scientists, anthropologists, psychologists, etc. regularly point out (as does the eye of the attentive observer of everyday life), not all people live in the same circumstances. Individuals have different social and economic backgrounds, and they are immersed in different social groups and cultures (e.g., Reckwitz 2002). With that, individuals have different interests, desires, fears, and anxieties. This can come along with distinct issues that are important to them at certain times (i.e., salient). Likewise, from a more fundamental and long-term perspective, distinct social backgrounds tend to imply different ways of socialization (e.g., Dalton 2017; Brady et al. 1995; Verba et al. 2004), and distinct views of life and how it should be (Thompson et al. 1990). Thompson et al. (1990) propose that it is likely to find sub-groups of citizens that share similar ideas of what issues are about politics based on shared socialization and similar (long-term) life circumstances.

Being immersed and growing up in certain social and life settings, people tend to develop distinct views about the roles and responsibilities of different institutions and actors in society, including that of politics and political actors (see Zorell 2020). In this way, socialization can affect whether a person conceptualizes an issue as a matter of politics in a general, rather permanent (though likely not eternal) way. This rather time-invariant perception contrasts with the more time-variant saliency. Depending on ongoing life events, a person may attribute different degrees of saliency to single matters, and with this, temporal attention to an issue. However, issues can be considered political by a person and yet not be salient to them, and vice-versa. Respectively, the conceptualization of politics can, but must not relate to whether a matter is (currently) salient to a person.

Studies exploring different understandings of a related term, ‘democracy’, show empirically that differences in the understanding of the concept are associated with different socio-demographic backgrounds (Ceka and Magalhães 2020). However, apart from the theoretical propositions by Thompson et al. (1990), the literature is essentially silent on how differences in life situations are related to differences in conceptions of politics. Considering this, we ask:

(RQ1) Can we distinguish systematic patterns or clusters of issues certain citizens conceptualize as politics? And can we differentiate groups of citizens with distinct conceptions of politics?

(RQ2) To what extent do people holding similar/different conceptions of what constitutes politics have similar/different socio-demographic backgrounds?

Concepts of politics and political participation

Conceptions of politics imply that citizens can view some issues as political while not others. Thompson et al. (1990) propose that what citizens regard as politics is socially negotiated among the inhabitants of a political culture, and these conceptions are related to behavior. Thus, according to them, conceptualizations of politics can act as underlying reasons for behavior. Correspondingly, if citizens do not regard something as political, they might not engage with it in a political sense. For example, a citizen may observe a problem, like environmental pollution from factory production, but not regard it as a matter of politics. This citizen may then not regard politic(ian)s as the ones responsible to address and solve the matter, but rather, e.g., the factory owner. Moreover, this person may probably not contemplate participating themself in a political action to, e.g., protest for environmental regulation of that factory, since in their view it is not about politics. In sum, different conceptions of politics may come along with different patterns in how people participate in politics, including the extent of participation and with respect to what issues.

A few empirical studies have followed such assumption and tested whether conceptions of politics influence political behavior. For instance, one study reports that those with a broad conception of politics, compared to those with a narrow conception, are more likely to participate in protest activities (Görtz and Dahl 2020). Relatedly, Coffé and Campbell (2019) identify two main sets of political activities (party- and non-party related activities) and show how engagement in each of them seems to explain very well (almost alone, apart from education) whether a person considers the kind of activities as political. One can also think about a reverse link. That is, understanding some topics as political while not others may trigger differentiated forms of political participation. Building on this, a last question we ask is:

(RQ3) To what extent do groups of people with different conceptions of politics differ in their patterns of political participation?

Data, variables, and methods

Our central assumption is that individuals’ conceptualization of politics differs not only in terms of breadth, but also in terms of content. Furthermore, we seek to explore if these differences are tied to the social backgrounds of the citizens, and if they imply distinct patterns of political participation. This being the to our knowledge first research with such purpose, we adopt an exploratory approach. Given the person-centered perspective of our research questions, we use individual survey data and combine several statistical methods.

Data and participants

We use original data from the “What is politics: United States” survey (Fitzgerald 2010). It was conducted among a representative sample of 1000 U.S. citizens by the survey institute YouGov during December 2010. This online survey included a particularly comprehensive battery of questions interrogating people’s perceptions of what issues they consider to be about politics. The measure addresses the issue to a deeper extent than any other existing survey known to the authors, thus fulfilling the main prerequisite to answer our research questions.

To improve the resemblance to the target population, the respondents were matched according to the key variables age, gender, race, and education, as well as to party identification, political interest, and ideology (using figures from the American Community Survey 2006).Footnote 3 YouGov provides respective descriptive weight variables, which we use throughout our analysis. As the use of online surveys in social sciences has increased, so have discussions about their advantages and disadvantages. However, when YouGov’s sampling procedure has been compared with random sampling surveys, the differences between them in terms of total survey error and coefficient estimates have shown, if present, to be rather small (see e.g., Ansolabehere and Schaffner 2014; Sanders et al. 2007). Such empirical results support that the data reach reasonable external validity. Moreover, online surveys often suffer from over-representation of politically interested participants (Couper 2000). Yet, the sample appears to reflect accurately representative survey data.Footnote 4 Thus, at least with respect to the U.S. context, we can generalize the results of our study with reasonable confidence.

Beyond the U.S. context, the possibilities to generalize are more restricted. For one, the specific contents that the surveyed citizens conceptualize as politics are likely to be a bit different in the U.S. context than in other country contexts, defined (also) by the political situation at the time of the survey. However, this would have been the same problem for any other country case studied, and a comparative study was not feasible at this time. As regards the political situation in the U.S. at the time of the survey, it was conducted halfway through the first term of the Democratic presidency of Barack Obama. Domestically, it was a time characterized by the economic crisis following the financial collapse of 2008, which gave rise to vivid debates about tax and healthcare reforms. In terms of foreign politics, main topics of concern were the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and the Transpacific Partnership trade agreement (e.g., Davies et al. 2017). These topics may thus have been particularly salient to survey respondents; but as mentioned, we are not so much interested in what people consider political at a certain time, but in identifying if different people have different understandings of what themes are political; and in our understanding, saliency does not automatically imply that the respondents also consider something political.

For another, the U.S. is notably stylized as home to citizens who embrace the view that the role of politics in society should be as limited as possible; much more than, for instance, in most European and Latin American countries (see e.g., Esping-Andersen 1990; Ferragina and Seeleib-Kaiser 2011; Böhm et al. 2013). Nonetheless, this makes it a least-likely case for uncovering groups of citizens with varying conceptions of politics. That is, if we can find in the U.S. context that there are not only citizens who have very narrow conceptions of politics, but also citizens with broad and differentiated definitions of what constitutes politics, then we may expect that such patterns can be replicated in other, politically more diverse contexts.

Measures

Conceptualization of politics

Questions toward how ‘politics’ is interpreted are not regularly included in ordinary surveys (O’Toole 2003; Manning 2010). However, in those cases where research has paid attention to citizens’ conceptualizations, at least two strategies prevail. The first is an open-ended approach, measuring peoples’ conceptualizations of politics by asking respondents to write down whatever they think of when they think of ‘politics’ (e.g., Morey and Eveland Jr. 2016; Henn et al. 2005). Another strategy, the more common one, is a topics-list approach. When citizens are asked to recall their interpretation of politics, a list of various topics is presented. Each topic, the respondents can categorize as either political or non-political. These lists often contain a broad spectrum of topics (e.g., Ferrin et al. 2020; Podschuweit and Jacobs 2017; Görtz and Dahl 2020; Fitzgerald 2013).

The survey we use followed the second approach. The specific question asked respondents to put themselves in the shoes of a political magazine editor and specify which topics they consider apt for being included in the politics section based on their assessment that a topic is ‘political’.Footnote 5 As magazines are associated with covering topical issues, we cannot entirely rule out the possibility that respondents were influenced in their selection by what they considered to be politically salient at that time. However, the question begs respondents explicitly to choose topics based solely on the consideration of whether they think a topic is political. We can therefore assume that the question assesses citizens’ conceptualization of politics. The question was followed by a list of 24 topics, of which for each the respondents could specify whether they consider them as political or not (i.e., ‘yes’ or ‘no’).Footnote 6 This dichotomous measurement follows the common procedure (e.g., Ferrín et al. 2020; Fitzgerald 2013), and it aligns with our research question, which is not about degrees of perceived ‘politicalness’.Footnote 7

The included topics came from two separate sources. About half of them are emphasized in the literatures on political behavior: unemployment (Clarke et al. 2005), childcare (Kershaw 2004), poverty (Iyengar 1990), education (Page and Shapiro 1983), same-sex marriage (Conover and Searing 2005), stem cell research (Nisbet 2005), public prayer (Huckfeldt 2007), global warming (Nisbet and Myers 2007), foreign aid (Taber et al. 2009), and energy (Bolsen and Cook 2008). To broaden the range of topics, Time Magazine was used as a second source of items. Specifically, a random sample of articles published between 2004 to 2009 was used as basis for picking topics to cover in the list of items (see Appendix).

According to the descriptive statistics (Fig. 1), the extent to which a topic is considered political varies considerably among respondents. None reached full agreement to be about politics, yet a vast majority categorized some of the topics as such. The top three most ticked were tax-cuts (82.5%), unemployment rates (75.1%), and terrorism (71.7%). At the other end were obesity, which was the one the fewest perceived belonging to the realm of politics (13.1%), followed by childcare (19.6%), and cancer research (21.8%). Interestingly, several topics tend to divide citizens rather evenly, among them same-sex marriage, global warming, and public school prayer.

Social background variables

We use three socio-demographic indicators in our analysis. Age, measured by one question asking the respondents to report their birth year. It was recoded into years of age (mean = 48.2, SD = 15.52), showing a range from 18 to 87 years. Second, income, which is tapped by an item asking respondents to indicate their family’s annual income over the past year. The respondents could choose from 14 income-levels, ranging from (1) less than $10.000 to (14) $150.000 or more (mean = 7.28, SD = 3.53).

Third, educational background is gauged asking respondents to report the highest level of education that they have completed. Six levels of education are provided: (1) ‘did not graduate from high school’, (2) ‘high school degree’, (3) ‘some college’, (4) ‘2-year college degree’, (5) ‘4-year college degree’, and (6) ‘postgraduate degree (e.g., MA, MBA, PhD)’. The mean level of education in the sample is 3.14 (SD = 1.44).

Furthermore, we include two variables to control for whether we are actually measuring distinct conceptualizations of politics, and not merely distinct degrees of interest in politics or distinct ideologies, which both could influence how many and/or which topics individuals consider being political. To measure people´s interest in politics, the survey includes a question asking: “Generally speaking, how interested would you say you are in politics?”. The respondents could then report on a 4-point scale whether they are (1) ‘not at all interested’ to (4) ‘very interested’ (mean = 3.0, SD = 0.89).

Political ideology is measured through a question asking respondents to categorize themselves on a 5-point scale between (1) ‘very liberal’ through (3) ‘moderate’ to (5) ‘very conservative’. The sample mean is 3.2 (SD = 1.10), thus tending slightly more toward conservativism than liberalism.

Political participation

We use nine indicators for assessing political engagement. Specifically, respondents were asked if in the past 12 months they have: donated money to charity, boycotted a product or company, signed a petition, voted in last local election, researched a candidate online, written a letter to the editor, voted in last mid-term election, and voted in a school board election. Moreover, one question asked whether the respondents are member of a political party. To all items, the possible answers are (1) ‘yes’ or (0) ‘no’. On average, people are involved in 3.33 activities (SD = 2.41).

Methods

Firstly, we are interested in whether certain topics come together as a bundle (RQ1), i.e., as closed clusters of topics that certain citizens regard as being about politics. Latent class analysis (LCA) permits to classify respondents according to some common pattern in how they respond to a set of (dichotomous) questions. However, when testing LCA with our data (using the statistical software StataBe 17), the result provided a one-dimensional geometric distinction of conceptualizations of politics. That is, the identified groups differed from each other in terms of numbers of items that they considered political, which corresponded to the extant distinction between narrow and broad conceptualizations of politics. However, it did not allow us to cluster individuals according to distinct combinations of topics which they consider political, which is what we are interested in. In contrast, cluster analysis permits for such an explorative approach, i.e., to uncover clusters of people who are both most similar within the cluster, and (most) different across clusters (Abdelzadeh and Ekman 2012).

Specifically, we carried out a two-step clustering approach with the statistical software SPSS28.Footnote 8 In step one, after standardizing the scores (z-score),Footnote 9 we applied the ‘elbow criterion’ to decide the proper number of clusters by running Ward’s hierarchical cluster analysis.Footnote 10 The calculation suggested the appropriate number of clusters to be five. In step two, with the detected number of clusters as a starting point, we performed K-means cluster analysis on the standardized scores to define clusters so that the total intra-cluster variation is minimized using Euclidean distance measure. This allows us to find coherent sub-groups of observations within a dataset without being ‘trained’ by a specific response variable. In detail, the K-means clustering technique tries to reduce the distance between the cluster center and variable scores, enabling identification of groups that share certain characteristics; in our case what individuals think of as ‘political’. As a consequence, respective groups of citizens are most similar to each other regarding their conceptions of what constitutes politics; while they are, on the same orientation, dissimilar to the other groups (clusters) of citizens (Abdelzadeh and Ekman 2012).

After identifying the clusters, we explored and compared the different clusters in terms of their social backgrounds (RQ2) and patterns of political participation (RQ3). To this end, we combined group mean comparison tests with multinomial logistic regression analysis.Footnote 11

Results

Citizens’ conceptions of what is political’

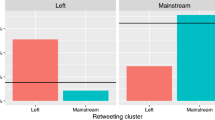

As the descriptive statistics above show, there is great variation in what topics are perceived as political. Yet, they tell little about whether some citizens hold systematically different conceptions of what is political than others. Identifying this requires a person-centered approach. The cluster analysis returns the five clusters presented in Fig. 2. Each of them stands for a common pattern of responses to all 24 topics.

A first group, here referred to as the conservative citizens (N = 185), scores comparatively high on long-established political topics center-staging most election campaigns.Footnote 12 Specifically, they score high on topics relating to traditional economic and social issues (e.g., poverty, cost of education, mortgage rates, unemployment rates), and on energy and security issues (oil drilling, solar technologies, nuclear weapons). In addition, it is one of only two groups that score above the mean on childcare and obesity. Meanwhile, the group scores low on topics such as refugees, foreign aid, the Green party, and Greenpeace.

The second group, whom we call nothing is political citizens (N = 149), consists of individuals that score very low on every single topic. In other words, this group of citizens considers nothing as political. Rather than speaking of perceptions that range from narrow to broad, we seem to have a group which lacks a conception of politics completely.

The global citizens (N = 238) have a broad conceptualization of politics, uniting mainly topics that relate to cross-national matters. Overall, they resemble a group of people typically considered as globalized left-wing oriented citizenry. It is the only group besides group five, which scores high on a ‘progressive’ mix of topics including same-sex marriage, foreign aid, refugees, the Green party, Greenpeace, stem cell research, terrorism, labor strikes, and public school prayer. At the same time, this group scores low on both cancer research and childcare.

The fourth group we label only tax-cuts are political citizens (N = 259), as they score comparatively low on all topics except for one: tax-cuts. Apparently, this group of citizens appears to consider nothing political but tax-cuts.

The last group, which we label everything is political citizens (N = 172), stands out in comparison with the others. It is the only group that scores very high on every single topic. Having ticked all sorts of topics as political, this group of citizens seems to have a highly political lens of the world and perceive their societal surroundings as generally political.

The distinction of these five groups proves not only that the peoples’ conceptions of how many issues are ‘political’ vary noticeably. It also illustrates that the content of what is considered as political varies systematically. This confirms our first research question, RQ1. The variation is particularly visible when comparing groups with somewhat similarly broad conceptualizations. Some citizens appear to define as politics mainly those topics that are ‘close-to-home’ and long-established, typical focus of media reports about domestic politics and party manifestos (group one). Other citizens, in turn, seem to conceptualize as political issues relating to national and international concerns alike (group three). Then, there are citizens who do not make such distinctions and seem to find political character in almost everything (group five) or (nearly) nothing (groups four and two).

To understand better what implications this finding may bear, the next section dives deeper into what distinguishes those groups and could—potentially—explain the distinct conceptualizations of politics.

Conceptualizations of politics and their social backgrounds

To analyze whether the identified groups differ in terms of their socio-demographic backgrounds (RQ2), we conduct group mean comparison tests. To see if differences are statistically significant, we employ Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) test.

As illustrated in Table 1, the ‘global citizens’ and especially those who consider ‘everything is political’ are citizens with particularly high levels of education. Also, these two and the ‘only tax-cuts are political citizens’ have relatively high incomes. In contrast, it is the two groups which do not draw boundaries between political and non-political spheres (the everything and the nothing is political citizens) which are comparatively young. However, the two groups differ notably in terms of their education and income. Those defining everything as political, have higher education and incomes than those considering nothing is political. At the other end of the age spectrum range the ‘conservative citizens’. They are, on average, the oldest (the difference is not statistically significant when compared with the ‘global’ and the ‘only tax-cuts are political’ citizens). Other than that, the ‘conservative citizens’ do not stand out in any direction in terms of education or income.Footnote 13

Table 1 also reports on political interest and ideological disposition. Little surprisingly, the ‘everything is political’ citizens are the ones that score highest on political interest. They are followed by the ‘global’ and the ‘conservative’ groups. However, the differences between these three groups are not statistically significant. In contrast, the ‘nothing is political’ group is the least interested in politics, thus underlining their apparent apathy toward politics. These differences are statistically significant in comparison with all other groups.

Some differences are also found when looking at ideological disposition. The ‘everything is political’ group is more ‘liberal’ than the citizens with a ‘nothing is political’, ‘only tax-cuts are political’, and ‘global’ conception. Interestingly, considering the more ‘conservative’ in the sense of long-established, conventional topics as political, shows to not necessarily imply that the citizens themselves are conservative in political orientation. On the contrary—those belonging to the ‘conservative’ cluster are roughly as liberal as those perceiving everything or nothing is political. The ones who show to be the most conservative are the ‘only tax-cuts are political’ citizens.

To examine the relation between social background factors and conceptions of politics further, we performed a multinomial regression analysis (Table 2). The cluster of those who consider ‘nothing is political’ is used as the reference category. The analysis underscores the patterns from the mean comparisons. Increasing age raises the probability of being a ‘conservative’ or ‘only tax-cuts are political’ citizen rather than someone who considers nothing as political. In contrast, age does not seem to increase the odds of having a ‘global’ or ‘everything is political’ conception. Instead, the likelihood of having a ‘global’ conception rather than viewing nothing as political increases with rising income. While increasing education seems to raise the odds that someone perceives everything rather than nothing as political.

A clearer pattern than that for the socio-demographic characteristics emerges for political interest. With increasing political interest, individuals also become more likely to have a broader conception of politics; that is, they become more likely to not regard nothing or only tax-cuts as political. Ideological disposition, in turn, does not show to uniquely predict group membership in any of the clusters.

In summary, political interest is a key factor that helps understand differences in conceptions of politics. Yet also, each group shows to differ in some (combination of) socio-demographic characteristic from the other groups. Hence, social backgrounds of groups seem to vary along with distinct combinations of contents that are considered political. This confirms our second research question, RQ2. Moreover, the latter point suggests that the clusters measure something more than only distinct degrees of political interest.

Conceptualizations of politics and political participation

Turning to the groups’ political engagement, Table 3 compares how the five groups fare on their political participation. Little surprisingly, the group of ‘nothing is political’ citizens is outstandingly inactive. This group is less engaged in electoral activities, donations, retrieving information about politicians, and signing petitions (where only the ‘only tax-cuts are political’ citizens range similarly low). Also, together with the ‘conservative’ and ‘only tax-cuts are political’ citizens, they are less engaged in political party activities. Interestingly, this group ranges comparatively high on only one form of political engagement: boycotting products or companies, reaching a mean value comparable to the ‘global’ citizens, and higher than the ‘conservative’ and the ‘only tax-cuts are political’ citizens.

There are also notable differences between the other four groups. The ‘everything is political citizens’ are more engaged in boycotting than any of the other groups. They are also more engaged in collecting information on political candidates, contacting news outlets, donating money, signing petitions, and being affiliated with a political party than the ‘conservative’ and ‘only tax-cuts are political’ citizens. These latter groups seem to limit their engagement to elections and charity. Finally, the ‘global citizens’ range on most activities in the middle, not standing out in any way.

In sum, we can overall affirm also our third research question, RQ3. We find noticeable and statistically significant differences in political participation of the different groups of citizens with distinct conceptions of politics. The patterns of participation do not only vary in the number of forms, but also in their combinations. In other words, the repertoires of participation seem to be fitted to the individuals’ distinct patterns of conceptualizing politics.

Discussion and conclusions

If political science is to make sense of politics in (democratic) societies, it is vital that scholars ground their analyses on coherent concepts (Goertz 2006) and continually explore citizen views and behavior. To feed this endeavor, in this study we generate insights into the ways in which individuals conceptualize the political realm in their own minds.

Leveraging a novel survey of U.S. Americans (N = 1000) that includes a battery of topics respondents can identify as political or non-political, we provide the to our knowledge first methodologically rigorous analysis of the different ways in which people conceptualize what is and what is not the stuff of politics. Five distinct clusters of individuals emerge. These distinct clusters indicate that it is not just the number of topics that differs among what people define as politics, but also the thematic compositions. Specifically, of the five groups which we identify, three reveal more or less similarly broad conceptualizations, yet they vary in terms of the contents, i.e., the topics that they conceptualize as political. In substantive terms, we show a distinction between ‘conservative’ citizens who consider domestic issues to be of relevance for politics, and ‘global’ citizens who view cross-national themes as political in nature. The former category represents a collection of citizens that use a more conservative—in the sense of conventional—lens to pick out political matters; hotly debated issues in political life associated with the economy, education, housing, and security populate the political concept in these people’s minds. In contrast, those in the latter category gravitate toward the environment, technology, foreign aid, and labor issues. Another collection of individuals view taxation as the defining issue of politics, reminiscent of the often-cited, minimalist summary of politics as “who gets what, when, and how” (Lasswell 1936).

We also identify two sets of citizens who do not discern the political from the apolitical among the thematic options before them. We refer to them as the ‘nothing is political’ and the ‘everything is political’ citizens. These clusters are just as interesting as those groupings who make substantive distinctions, yet the nature of their conceptualizations is a bit more puzzling. The ‘nothing is political’ citizens tend to be the lowest group on the educational scale and the engagement scale, while the ‘everything is political’ citizens are the highest on these scales. Yet, we can learn quite a bit from comparing them to each other. Those citizens who find nothing to be political, we think, are simply checked out from all things political. This is a meaningful orientation shared by a significant portion of the public also beyond the U.S. (see e.g., Amnå and Ekman 2014).

On the other end of the spectrum, the ‘everything is political’ crowd has the socio-economic and psychological resources to find political relevance in nearly all of the topics before them. They are also the most participatory across the full range of behavioral measures, a pattern that underscores the connection between participation across a range of activities and holding an expansive conceptualization of politics. We cannot speak to the direction of this relationship; panel survey would be a valuable addition to the political conceptualization literature. We should also acknowledge the possibility that those who find nothing or everything to be political in our survey might not be particularly invested in the activity. But we point to the correlations between these groupings and economic, psychological, and participatory characteristics to ground our logic that these are meaningful manifestations of political orientations.Footnote 14 As the nothing- and everything is political citizens are younger than those of the other groups are, it may be that with increasing age, individuals have lived experience with that may aid them in developing clearer and more demarcated definitions of what is and what is not political.

From a more general perspective, by illustrating the division in how groups in society conceptualize the political world, we shed light on the very nature of what people consider to be politics. Importantly, we show that those who share certain conceptualizations of politics, share socio-demographic, economic, and psychological characteristics that are known to matter for political behavior more generally. Respectively, we also see that cluster co-members share patterns of political behavior that align in important ways with their very foundational understandings of the political realm. This suggests that if we fail to account for this baseline nexus between people’s perceptions of politics and their participation in the political realm, we fail to fully understand their engagement with politics in day-to-day life. Put simply, understanding that people have systematically different, i.e., patterned, conceptualizations of politics can illuminate why certain people or groups of people do or do not get involved politically with certain matters. Such understanding can be crucial for researchers and practitioners who seek to address inequalities in political participation in more systematic ways.

A limitation of the study is the topics included in the questionnaire. The thematic compositions found are a product of the character of the 24 topics included in the survey, and of the population surveyed. Covering other topics, or more or less of them, may have created a somewhat different picture. However, this limitation applies to all studies on the topic. Thus, we clearly encourage future studies to dig further into this by looking at other themes and populations, while we are confident that the essential conclusion of this study remains strong. Comparing scales is perhaps also an interesting topic for future studies. This article, together with most of the previous ones, uses dichotomous answers. It could be beneficial to analyze and compare these types of answers with degree-scales, i.e., whether issues are perceived as more or less political. However, the only study which uses a different type of scale reports that most people considered different issues in a dichotomous way, i.e., as either ‘clearly political’ or ‘clearly private’, while there was little variation between the two extremes (Podschuweit and Jacobs 2017).

When people conceptualize politics, they make a series of judgments and draw on a complex set of considerations to make common sense of the public arena. By asking individual citizens to display the way they think, scholars can break new ground in service of understanding a range of foundational, psychological dispositions and processes. For those of us interested in political inputs and their resultant outcomes, taking stock of the varied, but principled, ways in which people draw boundaries around politics in their minds reveals meaningful diversity in citizens’ most basic connection to the political world around them.

Notes

The present study relies on this respective understanding.

65% of the respondents identified ‘aircraft noise’ as political, while 63% categorized ‘tram network’ as such (Podschuweit and Jacobs 2017). To be noted is that the German train company is partly state-owned.

For a more detailed description about the sampling procedure used by YouGov, see e.g. Rivers (2007).

Specifically, because of this tendency, we compared our sample with the distribution of political interest in the American National Election Study (ANES) pre-election survey, conducted between late September of 2007 to January 2008 (Prior 2019, pp. 1, 44–46). For instance, the share of “very interested” participants in our sample is almost identical to ANES, with about 35%. On the other end of the political interest spectrum, the share of participants that are “not at all interested” are 7.4% in our sample compared with close to 10% in the ANES. Participants that are fairly interested in politics are similarly large, with 40% in our sample and 35% in ANES. In sum, differences to the results from the general representative population survey are minor.

The exact wording of question is: “Imagine that you are the Editor of a political magazine. Your main job is to decide what kinds of stories to include in the magazine. Please look at the following article topics, and identify the ones that would be most applicable. In other words, choose the ones that are "political". This should be your only consideration”. Thus, respondents were not asked what they think ‘should’ or ‘could’ be political, but what they actually consider to be political. A potential problem can be that respondents just repeat what they observe as typical topics in the politics sections of magazines/newspapers they read. However, people’s attention tends to be drawn (and limited) to what appears relevant to them (e.g., Kahneman 2011). Therefore, we consider it reasonable to expect that respondents named—from a top-of-the-head view (e.g., Zaller 1992)—those topics which they personally regard as political.

We do not know whether the fictional role as an editor may influence respondents in their way of ticking political issues. However, the wording of the question made it explicit that respondents should think of what is considered political by them, rather than what an editor would think.

We do not know whether we ‘lose’ information using the dichotomous measure. Yet, the to our knowledge only study that so far uses a non-dichotomous measure revealed very little variance between the extremes (Podschuweit and Jacobs 2017). Despite being offered the possibility of grading their response, people seemed to answer in a dichotomous way. This is one study from one context (Germany), thus making it too early to draw strong conclusions about which is the best strategy. Yet, it also recalls that comparing 24 items for their degrees of ‘politicalness’ is cognitively extremely demanding. Results obtained through such an approach would thus need to be interpreted with great caution in terms of internal consistency and reliability.

This two-step clustering approach has been suggested by Punj and Steward (1983) and others. As a first step, a hierarchical method is run to decide an appropriate number of clusters. However, this method can be sensitive to outliers and thus create weaker results compared with non-hierarchical methods. Therefore, as a second step, the authors recommend refining the final clusters by employing K-means cluster analysis (see also Lega and Mengoni 2012; Hartigan and Wong 1979; Milligan 1980).

Z-score is calculated by the raw score minus the population mean, divided by the population standard deviation. Consequently, giving each score a mean-value.

Ward’s method is one of the most widely used hierarchical cluster methods for the purpose of generating clusters that minimize the within-cluster variance. The ‘elbow criterion’ (or elbow method) refers to a common rule for when it is most appropriate to stop merging new clusters, applied to determine the number of clusters (see e.g., Avros et al. 2012).

Interested readers can contact the main author for access to the data and syntaxes.

Due to the collection of notably traditional political topics, we decided to label this group ‘conservative’. This should not, however, be interpreted as party preference or ideology. None of the clusters exhibits a notable tendency towards one or the other ideological spectrum or party.

We also considered gender in the analysis. The mean values indicate that ‘conservative’ and ‘global’ citizens are slightly more women than men, while among the ‘everything is politics citizens’ are more men. However, the differences are not statistically significant and therefore not reported in the table.

How salient an issue is to people might be of importance in order to understand variations in people’s conceptions of politics better. That, however, is outside the scope of this study. Hence, for future research, analyses whether conceptions of politics are mediated by the extent to which issues are salient are more than welcomed.

References

Abdelzadeh, A., and J. Ekman. 2012. Understanding critical citizenship and other forms of public dissatisfaction: An alternative framework. Politics, Culture, and Socialization 3 (1–2): 177–194.

Almond, G.A., and S. Verba. 1963. The civic culture: Political attitudes and democracy in five nations. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Amnå, E., and J. Ekman. 2014. Standby citizens: Diverse faces of political passivity. European Political Science Review 6 (2): 261–281.

Ansolabehere, S., and B.F. Schaffner. 2014. Does survey mode still matter? Findings from a 2010 multi-mode comparison. Political Analysis 22 (3): 285–303.

Avros, R., O. Granichin, D. Shalymov, Z. Volkovich, and G.-W. Weber. 2012. Randomized algorithms of finding the true numbers of clusters based on Chebychev polynomial approximation. In Data mining: Foundations and intelligent paradigms. Volume 1: Clustering, association and classification, ed. D.E. Holmes and C.J. Lakhmi, 131–152. Berlin: Springer.

Bartolini, S. 2018. The political. London: Rowman and Littlefield/ECPR Press.

Böhm, K., A. Schmid, R. Götze, and C. Landwehr. 2013. Five types of OECD healthcare systems: Empirical results of a deductive classification. Health Policy 113 (3): 258–269.

Bolsen, T., and F.L. Cook. 2008. The polls—trends: Public opinion on energy policy: 1974–2006. Public Opinion Quarterly 72 (2): 364–388.

Brady, H., S. Verba, and K. Schlozman. 1995. Beyond SES: A resource model of political participation. American Political Science Review 89 (2): 271–294.

Ceka, B., and P. Magalhães. 2020. Do the rich and the poor have different conceptions of democracy? Socioeconomic status, inequality, and the political status quo. Comparative Politics 52 (3): 383–412.

Clarke, H.D., A. Kornberg, J. Macleod, and T. Scotto. 2005. Too close to call: Political choice in Canada, 2004. PS: Political Science & Politics 38 (2): 247–253.

Coffé, H., and R. Campbell. 2019. Understanding the link between citizens’ political engagement and their categorization of ‘political’ activities. British Politics. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41293-019-00116-5.

Conover, P., and D. Searing. 2005. Studying ‘everyday political talk’ in the deliberative system. Acta Politica 40 (3): 269–283.

Couper, M.P. 2000. Web surveys: A review of issues and approaches. The Public Opinion Quarterly 64 (4): 464–494.

Dalton, R.J. 2017. The participation gap: Social status and political inequality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Davies, M.A., K. Zheng, Y. Liu, and H. Levy. 2017. Public response to Obamacare on twitter. Journal of Medical Internet Research 19 (5): e167.

Doorenspleet, R. 2015. Where are the people? A call for people-centred concepts and measurements of democracy. Government and Opposition 50 (3): 469–494

Easton, D. 1975. A re-assessment of the concept of political support. British Journal of Political Science 5 (4): 435–457.

Esping-Andersen, G. 1990. The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Ferragina, E., and M. Seeleib-Kaiser. 2011. Welfare regime debate: Past, present, futures? Policy & Politics 39 (4): 583–611.

Ferrín, M., and H. Kriesi. 2016. How Europeans view and evaluate democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ferrín, M., M. Fraile, G.M. García-Albacete, and R. Gómez. 2020. The gender gap in political interest revisited. International Political Science Review 40 (4): 473–489.

Fitzgerald, J. 2010. What is politics: United States. Unpublished raw data.

Fitzgerald, J. 2013. What does ‘Political’ mean to you? Political Behavior 35 (3): 453–479.

Goertz, G. 2006. Social science concepts: A user’s guide. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Görtz, C., and V. Dahl. 2020. Perceptions of politics and their implications: Exploring the link between conceptualisations of politics and political participation. European Political Science. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-019-00240-2.

Hartigan, J.A., and M.A. Wong. 1979. Algorithm AS 136: A k-means clustering algorithm. Applied Stat 28 (1): 100–108.

Henn, M., M. Weinstein, and S. Forrest. 2005. Uninterested youth? Young people’s attitudes towards party politics in Britain. Political Studies 53 (3): 556–578.

Henn, M., M. Weinstein, and D. Wring. 2002. A generation apart? Youth and political participation in Britain. British Journal of Politics and International Relations 4 (3): 167–192.

Huckfeldt, R. 2007. Unanimity, discord, and the communication of political opinion. American Journal of Political Science 51 (4): 978–995.

Iyengar, S. 1990. Framing responsibility for political issues: The case of poverty. Political Behavior 12 (1): 19–40.

Kahneman, D. 2011. Thinking, fast and slow. London: Penguin Books.

Kavanagh, D. 1989. Political culture in Great Britain: The decline of the civic culture. In The civic culture revisited, ed. A. Almond and S. Verba, 124–176. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Kershaw, P. 2004. ‘Choice’ discourse in BC child care: Distancing policy from research. Canadian Journal of Political Science 37 (4): 927–950.

Lasswell, H.D. 1936. How gets what, when, how. New York: Whittlesey House.

Leftwich, A. 2008. Preface. In What is politics?, ed. A. Leftwich, 7–10. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Lega, F., and A. Mengoni. 2012. Profiling the different needs and expectations of patients for population-based medicine: A case study using segmentation analysis. BMC Health Services Research 12 (473): 1–12.

Manning, N. 2010. Tensions in young people’s conceptualization and practice politics. Sociological Research Online 15 (4): 55–64.

Mathé, N.E.H. 2017. Engagement, passivity and detachment: 16 year old students’ conceptions of politics and the relationship between people and politics. British Educational Research Journal 44 (1): 5–24.

Milligan, G.W. 1980. An examination of the effect of six types of error perturbation on fifteen clustering algorithms. Psychometrica 45 (3): 325–342.

Morey, A.C., and W.P. Jr Eveland. 2016. Measures of political talk frequency: Assessing reliability and meaning. Communication Methods and Measures 10 (1): 51–68.

Nisbet, M. 2005. The competition for worldviews: Values, information, and public support for stem cell research. International Journal of Public Opinion Research 17 (1): 91–112.

Nisbet, M., and T. Myers. 2007. The polls-trends: Twenty years of public opinion about global warming. Public Opinion Quarterly 71 (3): 444–470.

Norris, P. 2011. Democratic deficit: Critical citizens revisited. New York: Cambridge University Press.

O’Toole, T. 2003. Engaging with young people’s conceptions of the political. Children’s Geographies 1 (1): 71–90.

Page, B., and R. Shapiro. 1983. The effects of opinion on policy. The American Political Science Review 77 (1): 175–190.

Palonen, K. 2003. Four times of politics: Policy, polity, politicking, and politicization. Alternatives: Global, Local, Political 28 (2): 171–186.

Podschuweit, N., and I. Jacobs. 2017. “It’s about politics, stupid!”: Common understandings of interpersonal political communication. Communications 42 (4): 391–414.

Prior, M. 2019. Hocked: How politics captures people’s interest. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Punj, G., and D.W. Stewart. 1983. Cluster analysis in marketing research: Review and suggestions for application. Journal of Marketing Research 20 (2): 134–148.

Putnam, R.D. 2000. Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Reckwitz, A. 2002. Toward a theory of social practices: A development in culturalist theorizing. European Journal of Social Theory 5 (3): 243–263.

Rivers, D. 2007. Sampling for web surveys. Paper presented at the 2007 joint statistical meeting, Salt Lake City, July 29 to August 2.

Sanders, D., H.D. Clarke, M.C. Stewart, and P. Whiteley. 2007. Does mode matter for modeling political choice? Evidence from the 2005 British election study. Political Analysis 15 (3): 257–285.

Scruton, R. 2002. The meaning of conservatism. Indiana: St. Augustine’s Press.

Taber, C., D. Cann, and S. Kucsova. 2009. The motivated processing of political arguments. Political Behavior 31 (2): 137–155.

Thompson, M., R. Ellis, and A. Wildavsky. 1990. Cultural theory. New York: Routledge.

Verba, S., K. Schlozman, and H. Brady. 2004. Political equality: What do we know about it? In Social inequality, ed. K. Neckerman, 635–666. New York: Russell Sage.

Zaller, J.R. 1992. The nature and origins of mass opinion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Zorell, C. 2020. Reconfiguring responsibilities between state and market: How the ‘concept of the state’ affects political consumerism. Acta Politica 55: 560–586.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Örebro University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

The 24 topics

Cancer research | |

Use of tasers by police | |

Child care | |

Terrorism | |

Public school prayer | |

Tax cuts | |

Poverty | |

Foreign aid to Africa | |

The cost of education | |

Space exploration | |

Labor strikes | |

Obesity | |

The Green Party | |

Somali refugees | |

Mortgage rates | |

Global warming | |

Nuclear weapons | |

Stem cell research | |

Oil drilling | |

Solar energy technologies | |

Unemployment rates | |

Greenpeace | |

National parks | |

None of the above |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Görtz, C., Zorell, C.V. & Fitzgerald, J. Casting light on citizens’ conceptions of what is ‘political’. Acta Polit 58, 57–78 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-022-00233-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-022-00233-y