Abstract

Islamic assets, assets compliant with ethical and religious norms as codified in Sharia law, broaden the investor base. Do such investments contribute to mean-variance efficiency, and if so, how? Using daily data on stock, bond, and money market indices from nine Islamic countries and 37 non-Islamic ones from May 2007 to June 2010, we show that adding Islamic assets to an existing portfolio of conventional (non-Islamic) assets can expand the mean-variance frontier and thereby create additional value through diversification. The “specialness” of Islamic assets comes from a smaller set of common information and a lower degree of cross-market hedging between Islamic and conventional markets. This reduces volatility linkages between Islamic and conventional assets relative to volatility linkages between two conventional assets. Including one Islamic asset lowers volatility linkages by up to 3.16 percentage points after controlling for country-level fixed effects and time-varying characteristics. Low volatility linkages are key to increasing diversification benefits that arise from improvements in the global mean-variance portfolio. Our research contributes to the international business literature by highlighting the potential benefits of bridging religious, ethical, and cultural differences to add new markets to an incomplete international market structure and in so doing increase diversification benefits.

Résumé

Les actifs islamiques - actifs conformes aux normes religieuses et éthiques codifiées par la Charia - élargissent la base d'investisseurs. Ces investissements contribuent-ils à l'efficience de la moyenne-variance, et si oui, comment ? En utilisant des données quotidiennes sur les indices obligataires, monétaires et boursiers de 9 pays islamiques et de 37 pays non islamiques sur la période mai 2007–juin 2010, nous montrons que l'ajout d'actifs islamiques à un portefeuille existant d'actifs conventionnels (non islamiques) peut élargir la frontière de la moyenne-variance et créer ainsi une valeur additionnelle grâce à la diversification. La "spécificité" des actifs islamiques provient d'un ensemble plus restreint d'informations communes et d'un degré plus faible de couverture croisée entre les marchés islamiques et conventionnels. Cela réduit les liens de volatilité entre les actifs islamiques et conventionnels par rapport à ceux entre deux actifs conventionnels. L'inclusion d'un actif islamique réduit les liens de volatilité jusqu'à 3,16 points de pourcentage après avoir contrôlé des effets fixes au niveau du pays et des caractéristiques variables dans le temps. De faibles liens de volatilité sont essentiels pour accroître les avantages de la diversification lesquels découlent de l'amélioration du portefeuille global de moyenne-variance. Notre recherche contribue à la littérature des affaires internationales en soulignant les avantages potentiels de surmonter les différences religieuses, éthiques et culturelles pour ajouter de nouveaux marchés à une structure de marché internationale incomplète et ainsi accroître les avantages de la diversification.

Resumen

Los activos islámicos, activos que se amoldan a las normas ética y religiosas de la ley Sharía, amplían la base inversionistas. ¿Contribuyen esas inversiones a la eficiencia media-varianza? , y de ser así, ¿cómo? Usando datos diarios de mercado de valores, bonos e índices de mercado monetario de nueve países islámicos y 37 no islámicos desde mayo 2007 a junio 2010, mostramos que al agregar los activos islámicos a un portafolio existente de activos convencionales (no islámicos) se puede expandir la frontera media-varianza y por ende crear un valor adicional mediante la diversificación. Lo “especial” de los activos islámicos viene de un conjunto más pequeño de información común y un grado más bajo de de cobertura cruzada entre los mercados islámicos y los convencionales. Esto reduce los vínculos de volatilidad entre activos islámicos y convencionales en relación con los vínculos de volatilidad entre dos activos convencionales. La inclusión de un activo islámico reduce los vínculos de volatilidad hasta en 3,16 puntos porcentuales después de controlar los efectos fijos a nivel de país y las características variables en el tiempo. Los vínculos de baja volatilidad son clave para aumentar los beneficios de diversificación que surgen de las mejoras en la cartera global de varianza media. Nuestra investigación contribuye a la literatura de negocios internacionales al resaltar los beneficios potenciales de tender un puente entre las diferencias religiosas, éticas y culturales para agregar nuevos mercados a una estructura de mercado internacional incompleta y, al hacerlo, aumentar los beneficios de la diversificación.

Resumo

Ativos islâmicos, ativos em conformidade com normas éticas e religiosas codificadas na lei Sharia, ampliam a base de investidores. Esses investimentos contribuem para a eficiência da média-variância e, em caso afirmativo, como? Usando dados diários sobre índices de ações, títulos e mercados monetários de nove países islâmicos e 37 não islâmicos de maio de 2007 a junho de 2010, mostramos que adicionar ativos islâmicos a uma carteira existente de ativos convencionais (não islâmicos) pode expandir a fronteira da média-variância e, assim, criar valor adicional por meio da diversificação. A “especialidade” de ativos islâmicos vem de um conjunto menor de informações comuns e um menor grau de hedge entre mercados islâmicos e convencionais. Isso reduz conexões de volatilidade entre ativos islâmicos e convencionais em relação a conexões de volatilidade entre dois ativos convencionais. A inclusão de um ativo islâmico reduz conexões de volatilidade em até 3,16 pontos percentuais após controle de efeitos fixos em nível de país e de características variáveis no tempo. Conexões de baixa volatilidade são essenciais para aumentar benefícios de diversificação que surgem de melhorias no portfólio global de média-variância. Nossa pesquisa contribui para a literatura de negócios internacionais ao destacar os benefícios potenciais de eliminar diferenças religiosas, éticas e culturais para adicionar novos mercados a uma estrutura de mercado internacional incompleta e, ao fazê-lo, ampliar benefícios de diversificação.

摘要

伊斯兰资产, 即符合伊斯兰教法所规定的道德和宗教规范的资产, 扩大了投资者基础。 这些投资是否有助于均方差效率?如果有, 如何做到? 使用2007年5月至2010年6月间九个伊斯兰国家和37个非伊斯兰国家的股票、债券和货币市场指数的每日数据, 我们发现, 将伊斯兰资产添加到现有的常规 (非伊斯兰) 资产组合中, 可以扩大均方差边界, 从而通过多样化创造额外价值。 伊斯兰资产的“特殊性”来自于一组较小的公共信息, 以及伊斯兰市场和常规市场之间较低程度的跨市场对冲。 相对于两种常规资产之间的波动性联系来说, 这减少了伊斯兰资产和常规资产之间的波动性联系。 在控制了国家层面的固定效应和时间变量后, 包容一项伊斯兰资产可降低波动性联系3.16个百分点 。低波动性联系是提高全球均方差投资组合的改善所带来的多样化效益的关键。我们的研究突出了弥合宗教、伦理和文化差异的潜在好处, 为不完整的国际市场结构添加了新市场, 从而增加了多样化的好处, 为国际商务文献做出了贡献。

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

“As the 2008 Global Financial Crisis ravaged financial systems around the world, Islamic financial institutions were relatively untouched, protected by their fundamental operating principles of risk-sharing and the avoidance of leverage and speculative financial products.” (World Bank, 2015)

“The global Islamic finance industry proved resilient in 2020, the first year of the pandemic, with its total asset size jumping by 14% but it was in the following year that it showed even more character when growth of 17% out-performed pre-Covid levels to propel assets to US$4 trillion.” (ICD –Refinitiv, 2022)

While many previous financial crises were geographically contained, the impact of the US subprime crisis of 2007–2008 spread globally, decreasing diversification benefits worldwide. Financial markets had become more integrated over the previous decade, and this caused spread of contagion to other countries and economic sectors. The contagion effect translated into volatilities of most asset classes in most countries moving together. As a result, investors who held positions in different markets found themselves exposed to more than one kind of volatility risk, reminding investment and risk managers how crucial it is to assess the extent of correlation between volatilities of different asset classes.

We contribute to the literature by examining the volatility linkages between Islamic and conventional (non-Islamic) stock, bond, and money market indices in an international context. We also explore how the characteristics of Islamic financial markets affect those linkages. We use an extension of a stochastic volatility model in a generalized methods of moments (GMM) framework which derives volatility linkages from the relationship between information flows and volatility, and other robust methodologies such as a Kalman filter and dynamic correlations to estimate these volatility linkages. Volatility linkages are important because low correlations and low linkages are central to improving the global mean-variance portfolio and achieving diversification benefits. In particular, we test whether volatility linkages are lower when we include Islamic assets in an investment portfolio. Further, we employ the mean-variance spanning approach to test explicitly whether adding Islamic assets to an existing portfolio of conventional assets can expand the mean-variance frontier and thereby create additional value through diversification.

Our data on Islamic and conventional stock, bond, and money market indices cover nine Islamic countries, 37 non-Islamic countries and world indices between May 2007 and June 2010. We select this time period, first, as it includes the Global Financial Crisis of 2007–2008 with its high volatility and contagion across asset classes (e.g., Bauwens & Otranto, 2016; Cappiello, Engle, & Sheppard, 2006); and second, because of data availability. As it is, this is the most comprehensive dataset of Islamic assets, covering the largest number of countries for the longest period.1

We find that volatility linkages between indices of Islamic stocks and bonds and those of conventional assets (stocks, bonds, and money market instruments) are lower than those between two conventional assets. This difference is up to 26.33 percentage points (hereafter pp) in our univariate analysis, and up to 6.45 pp in our multivariate analysis. Even after controlling for country-level fixed effects and time-varying characteristics, the difference remains statistically significant and as large as 3.16 pp. We find similar results for cross-country volatility linkages. International volatility linkages between a US stock index and the Islamic stock index of another country are up to 2.44 pp lower than those between two conventional stock indices. We find that the diversification benefits of holding Islamic assets are higher when the issuing countries have lower derivative use, lower stock turnover, and higher market integration. Importantly, our results are not driven by the oil sector.

Second, we show that Islamic assets can provide diversification benefits by creating portfolios that expand the mean-variance frontier, particularly when they are issued by countries that have tight regulations and low political uncertainty. This is true both of diversification with Islamic assets within a given country or region, and internationally. These benefits are stronger in the case of Islamic bonds (sukuk) than Islamic stocks, and they arise primarily from improvements in the global minimum-variance portfolio. This has two implications for global investors: (1) Under the mean-variance valuation rule, Islamic assets create additional value; (2) The diversification benefits of holding Islamic assets in a portfolio of conventional assets cannot be replicated by holding only conventional assets.

We argue that there are two main reasons why volatility linkages between Islamic assets (stock and bond indices) and conventional assets (stock, bond, and money market indices) are lower than those between two sets of conventional assets (stock, bond, and money market indices). First, there is a smaller set of common information, i.e., information which simultaneously affects expectations across markets, between Islamic and conventional assets than that between two sets of conventional assets. Second, there is less cross-asset hedging with Islamic assets, and hence less information spillover. Because of these unique properties of Islamic assets, the volatility linkages between Islamic assets and conventional assets are lower. This in turn implies that portfolios that combine Islamic and conventional assets have an expanded mean-variance efficient frontier.

Islamic financial practices must be in keeping with socially responsible investment, and comply with Islamic law, sharia, which prohibits interest or usury (riba), opaque or unnecessarily risky transactions (gharar), gambling (qimar), and hence short selling, arbitrage, and speculation. Instead, Islamic bonds (sukuk) are based on profit-and-loss sharing and emphasize real rather than purely financial gains. Further, Islamic stock indices exclude firms that are seen as engaging in unethical behavior, such as alcoholic beverages, tobacco, gambling, weapons, and conventional financial institutions, as well as firms with high leverage and those which derive significant income from interest. These characteristics of Islamic stocks and bonds reduce the set of common information between Islamic and conventional markets because their volatility depends more on firm performance than on macroeconomic factors such as interest rates. There is also less cross-market hedging between Islamic and conventional markets because Sharia law prohibits speculation, short selling, gambling, and arbitrage, and also because Sharia-conscientious investors refrain from holding conventional assets, while conventional investors are also unlikely to hold a large amount of Islamic assets in their portfolios.

Our study makes an important contribution to the international business (IB) literature by highlighting an innovative way of enhancing diversification benefits in the face of growing global connectivity. Our finding that adding Islamic assets to an investment portfolio can provide diversification benefits makes a contribution to the international diversification literature in IB (e.g., Doukas & Kan, 2006; Gande, Schenzler, & Senbet, 2009) and to the literature on globalization, one of the oldest and most recurrent themes in IB (Verbeke, Coeurderoy, & Matt, 2018).

We show that using Islamic stocks and bonds is a useful risk-management strategy for multinational enterprises (MNEs) which scholars have shown to be vulnerable to various global risks (e.g., Kwok & Reeb, 2000; Mihov & Naranjo, 2019). This strategy is now feasible because Islamic finance is global, with Islamic assets spread over more than 80 countries (Domat, 2020). Further, our work is relevant to the IB literature with its emphasis on culture, market integration and other country-level factors (e.g., Chimenson, Tung, Panibratov, & Fang, 2022; Peterson, Søndergaard, & Kara, 2018). For example, we incorporate in our analysis market segmentation, capital development, country risk and culture. Our research also adds to IB literature on the impact of Islamic values on international business activities and entrepreneurship, such as the role of spirituality in Islamic business networks (Kurt, Sincovics, Sincovics, & Yamin, 2020), the role of religion in the internationalization of SMEs in Muslim countries (Younis, Dimitratos, & Elbanna, 2022) and the influence of Islamic Work Ethic on employees’ responses towards change (Al-Shamali, Irani, Haffar, Al-Shamali, & Al-Shamali, 2021).

Finally, our study contributes to the literature on global financial inclusion and poverty reduction. Despite substantial progress, financial access is still uneven in emerging countries (Beck, Senbet, & Simbanegavi, 2015). Islamic finance has the potential to increase financial inclusion and reduce poverty because it brings to the financial system those who self-exclude because of religious beliefs, and because of its risk-sharing principle, redistributive channels, microfinance, and micro-insurance (e.g., Shinkafi, Yahaya, & Sani, 2020; World Bank, 2015). It is also a potential solution to excessive debt and insolvency that can occur when using conventional financial instruments.

Our research is timely in that there is increased interest in global financial contagion and spillovers (e.g., Acemoglu, Ozdaglar, & Tahbaz-Salehi, 2015; Laborda & Olmo, 2021; Zhang, 2022). Our results complement this research and so have important economic implications, as financial crises are characterized by a strong flight to quality. As investors shift from stocks to bonds in the expectation that stock market volatility will increase, they still want to maintain the value of their invested capital and create additional value through efficient diversification strategies. The lower volatility linkages between Islamic and conventional assets (relative to those between two conventional assets) that we document in this study can provide lower risk exposures and diversification benefits. These can be an important consideration when devising international investment allocations and risk management strategies.

HYPOTHESES DEVELOPMENT

Volatility Linkages and Value-enhancing Diversification

In this section we discuss how combining Islamic assets with conventional assets, two categories of assets which have low volatility linkages with each other, leads to an expanded efficient frontier and higher diversification benefits. Grubel (1968) was the first to discuss the benefits of international diversification. His results have been confirmed and extended by others, including Errunza (1977), Errunza and Senbet (1984), Gande et al. (2009), and Solnik (1974), to name a few. The degree to which diversification can reduce risk depends on the correlation between the returns of the assets in the portfolio – an argument that has become increasingly important given the offsetting costs of globalization (Shaked, 1986). Diversification benefits are a major reason why investors prefer international equity funds over those that only focus on a specific region (Zhao, 2008). However, the benefits of global diversification have been offset by the increased connectivity of global financial markets, and this has led investors to search for new sources of diversification. Fortunately, integration of international financial markets has been accompanied by new financial products such as Islamic stocks and bonds, thus broadening the opportunity set for domestic investors. Our study provides fresh insight into the diversification benefits of including Islamic assets in a portfolio.

Volatility and volatility linkages are key properties of financial instruments and thus play a central role in finance. For example, volatility is crucially important in asset pricing models and dynamic hedging strategies as well as in the determination of options prices (Bollerslev, Chou, & Kroner, 1992). Accounting for volatility and related information correlations between asset classes is essential for portfolio and risk managers, derivative dealers, policy makers, and regulators. Low correlations and low volatility linkages between assets in a portfolio are key to achieving diversification benefits. In a mean-variance framework, diversification benefits are obtained when portfolio variance can be reduced without reducing expected returns. The diversification benefits of adding an extra asset in a portfolio are greater when the correlation between the new asset and the existing assets in a portfolio is small or negative. Therefore, we focus on low volatility linkages as an important channel through which Islamic assets can provide diversification benefits. As a further step, we measure empirically whether adding Islamic assets expand the mean-variance frontier and provide diversification benefits. We use the mean-variance spanning test to see whether the inclusion of Islamic assets expands the mean-variance frontier (see, e.g., Bekaert & Urias, 1996; Huberman & Kandel, 1987; Kan & Zhou, 2012).

Volatility linkages can be modelled as the information linkages between two markets, based on the proportional relation between volatility and information flow (Ross, 1989). Since information flows are unobservable, we use the speculative trading model developed by Fleming, Kirby and Ostdiek (1998), which is based on Tauchen and Pitts’s (1983) rational expectations trading model, and on the work of Andersen (1996) and Ross (1989). While Tauchen and Pitts (1983) consider a single futures contract, Fleming et al. (1998) generalize the model by letting investors trade in more than one futures market, and then use a stochastic volatility model to estimate volatility linkages between the stock, bond, and money market instruments. We do not consider futures contracts here, as derivatives remain controversial in most Islamic countries, and those that are traded are either based on commodities with actual physical delivery or are explicitly not compliant with Islamic law (Jobst, 2007; Zaher & Hassan, 2001). Instead, we extend the model to focus on the spot markets for stock, bond, and money instruments. In doing so, we build on the literature on volatility and information linkages, while also extending it to include Islamic assets.

Volatility linkages between asset classes, e.g., stock, bond, and money market instruments, arise when there is a set of common information between those markets that simultaneously affects expectations in more than one market, such as information on macroeconomic developments. A second source of volatility linkages is the information spillover caused by cross-market hedging. The latter occurs when investors operate in more than one asset class and respond to shocks in one market (e.g., the stock market) by optimally readjusting their portfolios by buying or selling assets from another asset market, for example bonds (Kodres & Pritsker, 2002). Fleming et al.’s (1998) stochastic volatility model predicts that volatility linkages will be stronger the more common information there is between different asset markets and the greater information spillovers.

Islamic Finance and Low Volatility Linkages

There are several reasons why volatility linkages between Islamic and conventional assets may be lower than those between two conventional assets. First, Islamic principles can lower the two drivers of volatility linkages, (1) the set of common information between different asset classes and (2) the degree of cross-market hedging. The prohibition of interest or usury, and the strong emphasis on the performance of underlying assets in determining the payoff to investors, have led to a smaller set of information that is common across Islamic and conventional assets compared to that across conventional assets. For example, information on interest rates, while not relevant for investors in Islamic assets, is important to investors in conventional assets (Akhtar, Akhtar, Jahromi, & John, 2017). Further, evidence suggests that Islamic stocks are less sensitive to political uncertainty and are more stable during financial crises than conventional stocks (Ahmed, 2018; Akhtar & Jahromi, 2017a). These studies suggest that Islamic assets are influenced by an entirely different set of factors, for example the personal income of Sharia-conscientious investors. Cross-asset hedging tends to be lower in Islamic markets due to the characteristics of Islamic finance, such as the prohibition of speculation, short selling, gambling, and arbitrage (Jobst, 2007). In particular, cross-asset hedging is lower between Islamic and conventional markets as Sharia-conscientious investors refrain from holding conventional assets, and conventional investors are unlikely to hold many Islamic assets in their portfolios.

Contemporary Islamic financial instruments were developed in the 1950s to allow billions of Muslims to conduct their financial affairs in a Sharia-compliant manner (Masood, 2021). They proved to be more versatile and resilient than their conventional counterparts during the COVID-19 pandemic (ICD –Refinitiv, 2022). In addition, due to the ethical character and inclusiveness of cultures (e.g., ‘Islamic labelled’ assets are readily available to all investors while conventional assets exclude Muslim investors) of Islamic financial instruments, there has been increasing demand for them beyond the Muslim world. This has created unique opportunities for diversification and for sustainability among multinational firms, “a powerful tool to boost climate action” as the Islamic Development Bank (2022) puts it.

In addition, there are structural differences between Islamic and conventional assets. Islamic bonds are investment certificates that are based on various forms of Islamic partnership and leasing arrangements.2 However, all of them are backed by tangible assets and the return on most of them is independent of interest rate movements but depends on the performance of the underlying assets.3 Further, there is growing evidence that returns on Islamic bonds are less volatile than those on conventional investment-grade bonds (Hassan, Paltrinieri, Dreassi, Miani, & Sclip, 2018). Sclip, Dreassi, Miani, and Paltrinieri (2016) consider Islamic bonds to be a separate asset class that is a hybrid of stocks and bonds.

To be included in an Islamic stock index, a stock must be in compliance with Sharia law. First, stocks of companies with businesses not compatible with the Islamic religion, such as alcoholic beverages, tobacco, weapons, gambling, and entertainment, as well as conventional banking and insurance, are excluded. Second, financial ratio filters are applied to exclude firms with large amounts of debt and interest income.4 A major distinction between Islamic and conventional (and socially responsible) stock indices is therefore that they include different types of firms (Forte & Miglietta, 2007). The exclusion of firms with high debt and interest income can also have a large impact on the performance of Islamic stocks relative to non-Islamic stocks (Akhtar & Jahromi, 2017b).

In sum, Islamic stock and bond indices include low-leveraged firms from selected industries whose performance is tightly linked to their underlying assets. This could affect volatility linkages because Islamic firms have different risk profiles and are subject to different regulations. Their volatility depends more on their performance than on macroeconomic factors like interest rates. Based on the above-mentioned characteristics of Islamic stock and bond indices, as well as on the impact of Islamic principles on the set of common information and on the extent of cross-asset hedging, we formulate the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1:

Volatility linkages between Islamic and conventional assets are lower than those between conventional assets.

Hypothesis 2:

Lower levels of common information and cross-market hedging will lead to lower volatility linkages between Islamic and conventional assets (compared to those between two conventional assets).

Hypothesis 3:

Diversifying using Islamic assets expands the mean-variance frontier and creates more value than that obtained by holding only conventional assets.

METHODOLOGY

Estimating Volatility Linkages

We estimate volatility linkages between asset pairs for all years in our sample and then test whether there is a significant difference between these linkages for different pairs of Islamic and conventional assets. We use four approaches to estimate volatility linkages within each country: (i) Pearson correlations, (ii) GMM estimates based on a stochastic volatility model, (iii) Kalman filter estimates based on the aforementioned GMM model and (iv) Dynamic correlations.

The first approach consists in computing volatility linkages for different pairs of assets as the Pearson correlations of the respective volatility series. We use daily data to build volatility series, which we proxy by the series of absolute returns, \(\left| {r_{k,t} } \right| = \left| {\ln \left( {\frac{{P_{k,t} }}{{P_{k,t - 1} }}} \right)} \right|\), or that of squared returns, \(\left( {r_{k,t} } \right)^{2} = \left( {\ln \left( {\frac{{P_{k,t} }}{{P_{k,t - 1} }}} \right)} \right)^{2}\), for each asset k (Pagan & Schwert, 1990; West & Cho, 1995).

Our second approach uses the stochastic volatility model of Fleming et al. (1998), with restrictions on the proportional relationship between information flows and volatility linkages. We apply the model to spot Islamic and conventional assets to examine how volatility linkages vary across these asset types. The stochastic volatility model, the moment restrictions, the GMM estimation, and seasonal adjustment procedures are described in online Appendix A. While various other approaches have been used in the literature to estimate contagion and spillover effects (e.g., Aït-Sahalia, Myckland, & Zhang, 2011), the methodology proposed by Fleming et al. (1998) is most relevant given our context and our daily data.

Our third approach is to apply the Kalman filter to the stochastic volatility specification described above and calibrate the filter using our GMM parameter estimates to obtain time-series estimates of daily information flows. A Kalman filter can generate more precise estimates than a GMM model when the sample period is short (Fleming et al., 1998).

The fourth approach involves dynamic correlations of absolute returns estimated using the methodology of Croux, Forni, and Reichlin (2001) based on spectral analysis. We use daily data, whereas those used by Croux et al. (2001) and related papers (e.g., Tripier, 2002) are quarterly or annual. We therefore choose comparable, but slightly different, frequency bands for the short-term, medium-term, and long-term correlations. For the short-term specifications we choose a frequency band of \(\left( {\frac{2}{5}\pi ,\;\pi } \right)\) which corresponds to cycles of 5 days or less, i.e., a standard week of 5 working days. We report our medium-term correlations on the frequency band \(\left( {\frac{1}{130}\pi ,\;\frac{2}{5}\pi } \right)\) which corresponds to cycles of between a week and a year. Our frequency band for long-term correlations is \(\left( {0,\frac{1}{130}\pi } \right)\), which corresponds to cycles longer than a year, i.e., business cycles. Our analysis also includes results for static correlations which are recovered from dynamic correlations on the frequency band \(\left( {0,\pi } \right)\) for better comparison with our estimates using other methodologies.

Testing Our Hypotheses

Univariate analysis

We use both univariate and multivariate analyses to test our first hypothesis that volatility linkages between Islamic and conventional assets are lower than those between conventional assets. The univariate analysis involves comparing series (i) and (ii), where (i) represents volatility linkages between conventional assets, and (ii) volatility linkages between an Islamic and a conventional asset, for example, the volatility linkage between conventional US stocks and conventional US bonds, minus the volatility linkage between Islamic US stocks and conventional US bonds. This yields 96 distinct difference terms. We then conduct paired t tests on the hypothesis that the difference terms are positive; that is, volatility linkages between any two conventional assets are stronger than those involving one conventional asset and one Islamic asset. While our main focus is on volatility linkages between different assets within the same country, we also include an analysis of international volatility linkages. To this end, we use Pearson correlations, GMM, Kalman filters, and dynamic correlations to estimate volatility linkages between US stock indices and those of other countries. For other combinations, we use Pearson correlations to estimate volatility linkages between one country and all other countries. We then test whether such linkages are lower when we include an Islamic asset.

We build several country-level proxies to test our second hypothesis that lower levels of common information and cross-market hedging will lead to lower volatility linkages between Islamic and conventional assets compared to those between two conventional assets. In integrated markets there tends to be a larger set of common information that affects different markets, so we use the reverse, market segmentation, to proxy for lack of common information. Following De Jong and De Roon (2005), we measure this by the share of a country’s assets which cannot be held by foreign investors. To proxy for cross-market hedging, we use indicators of capital market development, as cross-market hedging requires sufficiently liquid and developed financial markets (Fleming et al., 1998). More developed capital markets allow investors to operate in different financial markets within their country, and to more easily readjust their portfolios across different asset classes through cross-market hedging. For example, Guedhami, Knill, Megginson, and Senbet (2022) find that MNCs performed better during the COVID-19 pandemic in countries with more developed financial markets because they were able to access capital when their operations were shut down. We therefore use several indicators of capital market development used in prior literature and available for as many countries as possible: stock turnover for equity market development (e.g., Guedhami et al., 2022), credit to private sector for credit market development (e.g., Guedhami et al., 2022) and derivatives use as a proxy for hedging opportunities and futures-market liquidity (e.g., Bartram, 2019; Fleming et al., 1998). We divide countries into two groups (high and low) for each of those measures and test if there are statistically significant differences in diversification benefits between Islamic and conventional assets.5

Multivariate analysis

While the univariate analysis is based on our estimates of volatility linkages between asset pairs across the whole sample period, our multivariate tests are meant to capture the change in volatility linkages across time, while controlling for additional factors that may affect them. To this end, we estimate the following regression:

where \(\rho_{i,a,b,t}\): Monthly volatility linkage between assets a and b, in country i at time t.

\(I_{{\left\{ {{\text{Islamic}}\;{\text{Country}}} \right\}}}\!:\) Dummy variable that takes the value 1 if the volatility linkage is measured in an Islamic country and 0 otherwise.

\(I_{{\left\{ {{\text{Islamic}}\;{\text{Stock}}\;{{\& }}\;{\text{Islamic}}\;{\text{Bond}}} \right\}}}\), \(I_{{\left\{ {{\text{Islamic}}\;{\text{Stock}}\;{{\& }}\;{\text{Conventional}}\;{\text{Bond}}} \right\}}}\), and \(I_{{\left\{ {{\text{Islamic}}\;{\text{Bond}}\;{{\& }}\;{\text{Conventional}}\;{\text{Stock}}} \right\}}}\): Dummy variables that take the value 1 if the volatility linkage is measured with at least one Islamic asset. The control group is the case in which the volatility linkage is estimated between two conventional assets (stocks and bonds).

\(X_{it}\): Control variables that are intended to capture other factors that may affect volatility linkages through time and between countries to alleviate potential endogeneity issues. In some specifications, we also include country fixed effects. Details are provided in our discussion of the control variables and in Table 8 of Appendix A.

The dependent variable \(\rho_{i,a,b,t}\) is the monthly volatility linkage in country i at time t. It is measured as the monthly correlation between the daily return volatilities across any two assets a and b, where asset a is the Islamic or conventional stock index, and asset b is the Islamic or conventional bond index. The reason for using monthly correlations rather than correlations across the whole sample period (as in our univariate analysis) is that there is considerable variation in volatility linkages across time, which the multivariate analysis is intended to capture.

We repeat the exercise in Eq. (1) by applying it to the stock and money market index. To this end, we modify Eq. (1) by defining asset b as the money market index instead of the bond index. The control group is the volatility linkage between the conventional stock and the conventional money market index. Note that there are no Islamic money market indices. We obtain:

Hypothesis 1 states that volatility linkages between Islamic and conventional assets are lower than those between conventional assets. We therefore expect the coefficients of the Islamic asset variables to be negative and statistically significant (i.e., \(\beta_{2} < 0,{ }\beta_{3} < 0,{ }\beta_{4} < 0\) in Eq. (1) and \(\beta_{2} < 0\) in Eq. (2)).

Mean-variance spanning and value gains with Islamic assets

We use various statistical approaches to test whether adding Islamic assets to an investment portfolio expands the mean-variance portfolio constructed with conventional assets, and thereby provides additional value gains through diversification. We first use the mean-variance spanning test developed by Huberman and Kandel (1987) (HK test) and an extension of their test based on Kan and Zhou (2012) (KZ test), which includes a step-down test and a new spanning test based on GMM, and then the mean-variance spanning test developed by Barillas and Shanken (2017) (BS test).

The HK mean-variance spanning test investigates whether adding a new set of risky assets can allow a mean-variance investor to improve the minimum-variance frontier for a given set of risky assets. In other words, Huberman and Kandel (1987), in their multivariate framework, consider a set of K risky assets (the benchmark assets) which span a larger set of N + K risky assets if the minimum-variance frontier of the K assets is identical to the minimum-variance frontier of the K benchmark assets plus additional N assets (the test assets). \(R_{C,t}\) in Eq. (3) refers to a K-vector of the returns on the K benchmark assets (conventional assets), \(R_{IS,t}\) is the N-vector of the returns on the N test assets (Islamic assets), where \(E( \in_{t} ) = 0_{N}\) and \(E(_{t} R^{\prime}_{C,t} ) = O_{N \times K}\).

All returns are measured monthly. The necessary and sufficient conditions for spanning are \(\alpha = 0_{N}\) and \(\delta = 0_{N}\), where \(\delta = 1_{N} - \beta 1_{K}\).

Kan and Zhou (2012) propose a step-down test and a further GMM test, and subsequently apply these spanning tests to investigate whether diversification benefits can be obtained by expanding the set of investment assets. The step-down test gives additional insights into the traditional F-test, as there are two components. First, \({\text{F}}_{1}\) is a test of \(\alpha = 0_{N}\) , which provides evidence on whether the tangency portfolio can be improved, second, \({\text{F}}_{2}\) is a test of \(\delta = 0_{N}\) conditional on \(\alpha = 0_{N}\) , which provides evidence on whether the global minimum-variance portfolio can be improved. This test is exact if the residuals are normally distributed. The GMM test is preferred in case of conditional heteroscedasticity in the error term \(\in_{{\text{t}}}\). See Kan and Zhou (2012) for further explanations and derivations.

We apply the HK test, the KZ step-down test, and the GMM test for every country in our sample, where the benchmark assets are conventional assets (conventional stocks, bonds, and money market instruments), and the test assets are Islamic assets (Islamic stocks and bonds) which are added one at a time and then tested for joint significance where applicable. We also extend this analysis to consider conventional benchmark assets and Islamic tests assets from different countries.

In further analysis, we apply the BS test to examine whether the Islamic index expands the mean-variance frontier constructed with conventional assets. We perform this test for every country, and extend it to multivariate tests for multiple countries within a given region. For country-level analyses, we regress the excess return of the country’s Islamic index portfolio on the excess return of the market portfolio, i.e., the conventional world index, as well as the international factors from the Fama–French three-factor model. These factors include the high minus low (HML) value premium, i.e., the spread in returns between companies with a high versus low book-to-market ratio, and the small minus big (SMB) premium to capture the outperformance of small firms relative to larger firms over the long-term.6 While the international HML and SMB portfolio returns are not available for each country, we match a country to the region or group of countries – North America, Europe, Asia-Pacific (except Japan), economically developed countries, emerging countries – into which it best fits. We also include an intercept, and test whether it is strictly positive (rather than non-zero), indicating that a long position in Islamic assets can expand the mean-variance frontier. More formally, we estimate Eq. (4) and test for \(\alpha_{i} > 0\) for each country i, where \(R_{t}^{IS}\) is the Islamic index return, \(rf_{t}\) is the 1-month US Treasury bill rate, and \(R_{t}^{{{\text{market}}}}\), \(HML_{j,t}\) and \(SMB_{j,t}\) are the three-factor portfolios for region j, all in monthly frequency.

DATA

Data Collection and Adjustments

We collect daily return data on conventional stock, bond, and money market indices for nine Islamic countries, 37 non-Islamic countries, and for world indices. We select our sample to include the largest number of countries over the longest period, subject to data availability, to support credible international generalization (Franke & Richey, 2010). Each country in our sample has data on an Islamic and a conventional stock index, and on a conventional bond index. We also include an Islamic bond index and a conventional money market index, when available. Islamic bond indices are available for Malaysia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), and the world. The sample period is from May 31, 2007 to June 8, 2010. Table 8 gives data availability and sources.

Several research studies document the importance of exchange rate in the financial market and in IB literature (e.g., Faff & Marshall, 2005; Granger, Huang, & Yang, 2000; Hutson & Stevenson, 2010). To make volatilities comparable across countries, all returns are converted into US dollars using the respective exchange rate. Weekends in the countries of the GCC are taken on Fridays and Saturdays, so we exclude Fridays from the GCC, Qatar and UAE entries. We also exclude public holidays. We create a daily return series for each asset k as the log of price relatives: \(r_{k,t} = \ln \left( {\frac{{P_{k,t} }}{{P_{k, t - 1} }}} \right)\). Table 9 in Appendix A provides the number of observations and the annualized returns and volatilities for a subset of countries.

Control Variables

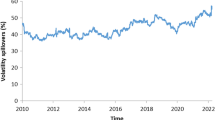

We include the following control variables to capture factors that may affect volatility linkages over time and across countries: sovereign credit ratings, country risk, periods of high volatility, exchange rate volatility, GDP per capita, ease of doing business indices, extent of corruption, foreign direct investment inflows, average effective bid–ask spread, corporate bond dummy, money market dummy, dummy for the mandatory use of International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), political stability, and Hofstede’s six dimensions of culture. According to Fleming et al. (1998), volatility linkages are determined by the set of common information that shapes expectations across financial markets, and by information spillovers caused by cross-market hedging. The set of information common to stock, bond, and money market indices depends on the underlying assets. For example, a bond index may include government or corporate bonds, and bonds with different maturities. We control for this by including an indicator variable for corporate bonds in equations (1) and (2). We include several variables to capture the degree of market uncertainty that affects the sensitivity of stocks, bonds, and money market instruments to common information, namely sovereign credit ratings, country risk, periods of high and low volatility, exchange rate volatility, and GDP per capita.7 Transaction costs, institutional constraints, information barriers, and market liquidity (e.g., Kanas, 2000) have been shown to affect cross-market hedging. We measure these with an “ease of doing business” index, a corruption index, and foreign direct investment. We also include proxies for whether a country has mandated IFRS, for political stability and absence of violence and terrorism, and for country culture measured by Hofstede’s six dimensions. The proxy for market liquidity is the effective bid–ask spread computed on daily security prices (Roll, 1984). Our final specifications are estimated either with or without country-level fixed effects. All specifications and data sources for the control variables are summarized in Table 8 of Appendix A.

EMPIRICAL RESULTS

Analysis of Volatility Linkages

We conduct multiple analyses to test whether Islamic assets have significantly different volatility linkages. We consider the difference between the volatility correlations between two conventional assets and those between an Islamic asset and a conventional one. We estimate volatility linkages across the whole sample period using (1) Pearson correlations with volatility measured as either absolute or squared returns; (2) the stochastic volatility model of Fleming et al. (1998) in a GMM setting and Kalman filter; and (3) dynamic correlations (derived static correlations; long-term, medium-term, and short-term dynamic correlations), in each case controlling for lead and lag effects. Based on the reasoning presented in previous sections, we expect the mean of these differences to be significant and positive. Examples of volatility linkages calculated through all eight methods are presented in Table B.1 in online Appendix B. It shows that volatility linkages are lower when we include Islamic assets.

Volatility linkages by asset type

Table 1 presents our first set of results where we test our first hypothesis that volatility linkages between one Islamic asset index and one conventional asset index are lower than volatility linkages between two conventional asset indices. They confirm the hypothesis as most of our estimated difference terms are positive and statistically significant, and this holds when volatility linkages are estimated between two classes of assets within a country as well as between assets in two different countries. In the former case, we find that volatility linkages involving at least one Islamic asset index are on average 3.04 to 15.61 pp lower than those between two conventional asset indices, and these differences are significantly different from zero at the 1% level for all methodologies (column 1). Volatility linkages between an Islamic stock index and a conventional asset index (columns 2 to 4) are 1.72 to 26.33 pp lower than those between two conventional asset indices, while those between an Islamic bond index and a conventional asset index (column 5) are 5.30 to 10.45 pp lower than those between two conventional indices. We find similar results when we examine whether volatility linkages between a conventional US stock index and that of another country are lower when one of the stock indices is an Islamic one. As shown in column 6, Islamic assets provide diversification benefits of up to 2.44 pp in our cross-country comparisons.

We also conduct more detailed analyses of differences in volatility linkages, which we present in online Appendix B. First, we calculate differences in volatility linkages by subtracting volatility linkages between two Islamic assets (instead of volatility linkages between one Islamic and one conventional asset) from volatility linkages between two conventional assets. We find even larger differences in this case, as shown in Tables B.2 and B.3 in online Appendix B. Second, our main hypothesis that volatility linkages differ between Islamic and conventional assets can be expanded to assess whether this difference is greater in Islamic countries. Table B.2 (columns 3, 4, 6, and 7) and Table B.4 in online Appendix B confirm that our first hypothesis holds in both Islamic and non-Islamic countries, but that diversification benefits are somewhat larger in Islamic countries. We also calculate differences in volatility linkages between Islamic and conventional assets in relative terms (percentages) and compare those across Islamic and non-Islamic countries. We find consistent results as presented in Table B.5 in online Appendix B. Third, we expand the cross-country analysis to all 47 countries and regions in our sample and present these cross-country linkages of absolute returns in Table B.3 in online Appendix B.8 These results again support our first hypothesis as most of these differences are positive and statistically significant. Differences for 40 countries and regions (out of 47) are statistically significant at a 1% level of confidence when using standard t-statistics – and differences for 45 countries when using bootstrapped t-statistics.

Market segmentation and cross-market hedging

Results in Table 2 mostly confirm our second hypothesis that lower levels of common information and cross-market hedging will lead to lower volatility linkages between Islamic and conventional assets compared to those between two conventional assets. First, using market segmentation as a proxy for the availability of common information, and measuring it by a country’s share of non-investible assets, we find that holding Islamic assets provides higher diversification benefits by up to 5.40 pp in countries with lower market segmentation. This is consistent with the idea that countries with more integrated markets, and hence where there is more common information, have higher volatility linkages. Second, we find that holding Islamic assets has greater diversification benefits in countries with less developed capital markets, especially when measured by the number of stocks traded and the use of derivatives. For example, the diversification benefits of holding Islamic assets are 2.89 pp higher in countries with low use of derivatives. It appears that lower hedging leads to higher risk and higher volatilities, and this in turn translates into higher volatility linkages and larger differences between Islamic and conventional assets. As such, Islamic assets provide more benefits in countries with lower derivatives use and offset the lack of hedging opportunities. We also calculate differences in volatility linkages between Islamic and conventional assets in relative terms (percentages) and compare these across the various sub-samples. We find consistent results, as presented in Table B.7 of online Appendix B.

Multivariate analysis of volatility linkages

We extend the univariate analysis to a multivariate setup as described by equations (1) and (2), where we allow volatility linkages to change monthly. Since we need monthly values for volatility linkages, the volatility correlations are estimated at this frequency using the Pearson correlation (with either the absolute returns or the squared returns as the volatility proxy). Table 3 presents our results for volatility linkages between stock and bond markets (Panel A) and for those between stock and money market instruments (Panel B).9 Our main variables are dummies that capture differences in volatility linkages between Islamic and conventional assets. We find support for our first hypothesis that volatility linkages between one Islamic asset index and one conventional asset index are lower than volatility linkages between two conventional asset indices. From the IB literature perspective, this result is consistent with the safe haven property of Islamic assets (e.g., resilient and efficient during highly volatile market) that is central to value additive diversification benefits. In this instance, fund managers can deploy Islamic assets to minimize their risk exposure during uncertain times, while being inclusive to cultural and religious diversity at the same time. Volatility linkages between Islamic stock and conventional bond indices are lower by 2.03 to 2.55 pp than those between conventional stock and bond indices. Further, volatility linkages between conventional stock and Islamic bond indices tend to be lower than those between conventional stock and bond indices by 3.70 to 6.45 pp. Likewise, volatility linkages between Islamic stock and conventional money market indices are lower than those between conventional stock and money market indices by 2.39 to 3.18 pp. The country fixed effects and the control variables provide significant additional explanatory power, and most of them are statistically significant. In both markets, volatility linkages are strongest when market frictions are low, the liquidity and volatility of the underlying assets are high, and during times of uncertainty and crisis.

Value Gains from Diversification with Islamic Assets

We now test our third hypothesis that including Islamic assets in a portfolio expands the mean-variance frontier and creates more value in terms of diversification benefits than that obtained by only using a portfolio of conventional assets. To this end, we estimate the mean-variance spanning test developed by Huberman and Kandel (1987) and its extension by Kan and Zhou (2012), as well as the Barillas and Shanken (2017) test.

Diversifying with Islamic assets within the same country

Table 4 presents results for the HK test, the KZ step-down test and the KZ GMM test for each country in our sample, where the benchmark assets are conventional assets (e.g., conventional stocks, corporate bonds, government bonds, and money market instruments), and the test assets are Islamic assets (e.g., stocks and bonds) which are added one at a time and then tested for joint significance (where applicable).

We begin by choosing the conventional world stock index and the conventional world bond index as our benchmark assets and an Islamic world stock index and an Islamic world bond index as our test assets (as shown in the first three rows in Table 4). The HK and KZ step down tests suggest that Islamic bonds can provide diversification benefits. In particular, there is evidence that the global minimum-variance portfolio can be improved by including an Islamic world stock index. We find consistent evidence across all three tests that adding both Islamic stocks and Islamic bonds provide diversification benefits. This is consistent with our argument that Islamic assets can provide diversification benefits while maintaining solid returns for fund managers, investors, and multinational firms. The benefits arise primarily from improvements in the global minimum-variance portfolio (\({F}_{2}=5.467\), P value = 0.009) although there is some evidence at the 10% level that there are also benefits from improvements in the tangency portfolio (\({F}_{1}=2.554\), P value = 0.093). There is also evidence that adding Islamic assets to Australian, Austrian, Italian, Japanese, Moroccan, Dutch, Russian, South Korean, Swedish, UAE and UK portfolios provides diversification benefits. These benefits mostly arise from improvements in the global minimum-variance portfolio. According to the mean-variance valuation rule, this provides incremental value to the diversifying investors that they could not have had without Islamic assets. In further analysis we identify some factors that increase the probability of high diversification benefits. Private credit bureau coverage, the extent of corporate disclosure, and the strength of investor protection have a positive effect, while country risk and country-level economic variables have no effect.10

We also apply the BS test to examine whether the Islamic index expands the mean-variance frontier constructed with conventional assets. First, we conduct this test on an individual country level (see Panel A of Table B.10 in online Appendix B). There is evidence that Islamic assets can expand the mean-variance frontier in Chile, China and Denmark (at the 5% level), and Australia, Colombia, India and Singapore (at 10% level), although this is not significant in our joint multivariate tests by world regions (i.e., North America (NA), Europe (EU), Asia-Pacific excluding Japan (AP), Developed (DE) and Emerging (EM) countries). In further analysis we find that indices for the extent of corporate disclosure and enforcement of contracts, measures of political uncertainty, and whether firms adopted IFRS, increase the probability of expanding diversification benefits while country risk has no impact.

In online Appendix C we provide further statistical tests and graphical illustrations that show that Islamic assets are similar to conventional assets in terms of mean-variance efficiency while also being relatively closer to the global minimum variance portfolio. This suggests that they create additional value without utility loss for Muslim investors despite restricting their investment choice.

Diversifying with Islamic assets across countries

Investors may also consider diversifying with Islamic assets from different countries. We conduct several tests to investigate whether this provides diversification benefits. First, we look at the case of investors in the United States who hold a portfolio of conventional assets issued in the United States and in one additional foreign country or region. We test whether adding to their portfolio Islamic assets issued in that additional country or region yields diversification benefits. This allows us to focus on the incremental benefits of diversification with Islamic assets, as opposed to international diversification in general. The results in Table 5 show that including Islamic assets, in particular Islamic bonds from other countries or regions, provides diversification benefits. This implies that a conventional investor who has already diversified their portfolio with foreign assets can gain additional benefits by including Islamic assets due to their unique characteristics. For comparison purposes, we also test whether just adding foreign conventional assets to a portfolio of conventional assets issued in the United States provides similar diversification benefits, but find that this is generally not the case (see Table B.11 in online Appendix B).

Second, we look at investors from each of our 47 countries and regions who hold domestic conventional assets, and consider diversifying their portfolio with all four Islamic bond indices (GCC, Malaysia, the UAE, and a World Index). Table 6 presents results of joint tests, where investors choose to add all four to their conventional portfolio. More detailed results, including the estimated \(\widehat{\alpha }\) and \(\widehat{\delta }\) coefficients as well as the test statistics and P values for each individual Islamic bond index are available in Table B.12 of online Appendix B, where we also consider the case where investors add only one of the four to their conventional portfolio at a time. The HK test shows that there are substantial diversification benefits from adding Islamic bonds to a portfolio of conventional assets as the P values for all of our 47 countries and regions are less than 1%. The KZ step-down test shows that the benefits arise primarily from improvements in the global minimum-variance portfolio as the P values of the \({F}_{2}\) statistic in the KZ step-down test and the \({W}_{a}\) statistic in the KZ GMM test are all (but one) less than 1%. The KZ GMM test indicates improvements in the tangency portfolio, with 45 out of 47 P values for the \({W}_{a}^{e}\) statistic below 5% and 42 below 1% (Table 6).

In a third test we consider the case of investors who hold conventional assets from their own country or region and conventional stock and bond world indices. In Table 7, we analyze what happens when they add to their portfolio Islamic stock and bond world indices. We find that even when investors hold a well-diversified portfolio of domestic and foreign assets, diversifying with Islamic bonds provides additional value for investors located in 33 out of the 46 countries and regions in our sample, including the United States (with P values less than 10% for the HZ test). This evidence further provides re-assurance that Islamic assets have enormous potential for international investors and multinational firms. In particular, we may also see more frequent issuance of dedicated social Islamic finance instruments, such as green Islamic bonds, as the Islamic finance industry commits to environmental, social, and governance (ESG) goals (S&P Global, 2022).

ROBUSTNESS ANALYSIS AND FUTURE EXTENSIONS

One might argue that Islamic equity indices are heavily dominated by the oil index and hence that our results are driven by it. To investigate that possibility, we orthogonalize each country’s equity index on the oil index (see Table B.13 in online Appendix B). The results are unchanged.

Second, we divide our sample into a crisis period and non-crisis period, using March 17, 2008 as the start of the crisis – the date on which US investment bank Bear Stearns was taken over by JP Morgan – and June 8, 2010, the last day in our sample. Table B.14 in online Appendix B shows that our results remain robust across these two time periods.11 Table B.15 in online Appendix B shows that while the returns to Islamic equities were lower and had a higher standard deviation during the crisis, they were nonetheless marginally better than those of conventional equities.

As an additional robustness check, we estimate volatility linkages via correlations between GARCH-implied volatility series. As shown in Table B.16 in online Appendix B, results are robust, although not as significant as in Table 1 (but note that we are working with implied volatilities, not realized ones).12 We also verify that our results are not driven by conversion into US dollars.13

Islamic assets have benefits that we have not captured in this study that could be an interesting extension for future work. Islamic assets include unique features of social impact investment such as targeted measurable and tangible outcomes, innovation, partnership and investment that creates jobs and helps to alleviate poverty and inequality. This is because firms that follow Islamic principles are required to pay part of the firm’s profit to benefit society (Gözübüyük, Kock, & Ünal, 2020). The strong emphasis on ethics in Islamic finance makes it responsive to ongoing environmental challenges (Maksimov, Wang, & Yan, 2022; Rugman & Verbeke, 1998). In particular, Islamic finance has a strong potential to support climate action because of its focus on tangible assets (Islamic Development Bank, 2022). For example, Green Islamic Corporate Bonds aim to protect the environment, and have been issued by large international firms for water management in Malaysia (Alam, Duygun, & Ariss, 2016). Researchers may examine how their performance compares to that of conventional green bonds. Islamic bonds are also financing infrastructure projects across Africa and contributing to socially useful projects across the continent. Table 11 in Appendix A shows that Islamic firms have higher ESG scores than other firms. In particular, the returns and volatility of the Islamic world equity index explain the largest portion of the variation of our two ESG indices, which implies that Islamic equity indices carry a unique property of social value creation at market level which to date has been unexplored. Further, Islamic assets provide greater compliance with targeted measurable outcomes and hence offer less room for corruption than conventional bonds. With Islamic assets, holders cannot divert issued funds for any other purpose. Future research can examine how the issuing of Islamic bonds contributes to economic development. Further benefits include higher financial inclusion, especially in Middle Eastern, African, and Asian countries with large Muslim populations where would-be investors may not enter the financial sector because they are concerned that doing so may not be in keeping with their religious beliefs.

CONCLUSION

Despite repeated injection of billions of dollars into markets by central banks on both sides of the Atlantic, recent financial crises have resulted in unprecedented stock market volatility. Most asset classes have experienced significant losses and volatility, with strong cross-correlations. This phenomenon translated into the rapid spread of volatility through global financial markets. No sector remains unscathed, and yet, financial contagion seems to have affected Islamic assets to a lesser degree. While there has been research on volatility linkages and on Islamic finance, we contribute to the literature by analyzing them jointly. We examine how volatility linkages across stock, bond, and money market indices differ between Islamic and conventional assets and how these differences can create value for investors through diversification.

We find that volatility linkages are weaker between Islamic and conventional assets compared to those between two conventional assets due to a smaller set of common information and lower cross-market hedging activity between Islamic and conventional markets. We document that including one Islamic asset in a portfolio lowers volatility linkages by up to 3.16 pp after controlling for country-level fixed effects and time-varying characteristics. We find larger differences in volatility linkages in countries with lower derivative use, lower stock turnover, and lower financial market segmentation. Our results are not driven by the oil sector.

We show that Islamic assets can provide diversification benefits as many of the available Islamic assets are not included in the linear span of the remaining conventional assets. In particular, we show that while Islamic assets are similar to conventional assets in terms of mean-variance efficiency, they tend to be closer to the global minimum-variance portfolio. Including Islamic assets, particularly Islamic bonds, expands the mean-variance efficient frontier, especially in countries where there are relatively tight financial regulations and comparatively low political uncertainty.

The diversification benefits of Islamic assets should be of interest to IB scholars as there is potential to replicate some of these benefits on a broad scale by making good use of some Islamic finance features such as an emphasis on ethics, good risk management, and good governance. This is particularly relevant for MNEs and other international investors. Our research contributes to the IB literature by highlighting the potential role that religion, ethics and cross-country cultural differences can play in financial innovation and value creation in global financial markets. The governance of Islamic financial instruments, strongly influenced by Islamic principles, is built on ethics, social responsibility, transparency and the avoidance of unnecessary uncertainty and risk taking. Such governance could bring about greater stability and efficiency in the global financial system. Diversification and hedging strategies are at the core of risk management. Our findings have important implications for IB investment and risk management, especially in view of the increasing popularity of Islamic finance both within and beyond Islamic countries. For example, we show that the inclusion of an Islamic asset reduces information linkages with conventional assets. Managers, hedgers, investors and shareholders can use this strategy to minimize the risk exposure of their net investment position and reap the benefit of diversification.

Our findings have asset pricing implications on valuation effects of MNC diversification and segmentation. One application is the pricing of country funds which depends on diversification benefits and the spanning ability of freely tradable securities (Errunza & Senbet, 1981, 1984). The asset pricing implications of our findings go beyond diversification and mean-variance spanning. The special characteristics of Islamic assets and the demand for them suggest that they can be studied using Koijen and Yogo’s (2019) demand system approach, which is used to study the price effects of index inclusion, ESG driven cash flows, and the prices of assets that have “specialness” (e.g., van der Beck, 2022). Therefore, future research could extend our study by examining how certain “specialness” attributes of Islamic assets are integrated into ESG criteria. This could potentially pave the way for achieving some of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals.

NOTES

-

1.

The sample period cannot be extended because some index data and other variables required for the analysis are no longer available, e.g., the Islamic bonds that are central to our analysis. The sample period includes the Global Financial Crisis – a time characterized by high volatility. If the required data should again become available, future research could explore if the results can be generalized to other crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Our robustness section extends some of the analysis going back to 1999 and finds consistent results during a period of lower volatility (see Table C.18 in online Appendix C).

-

2.

Under leasing arrangements, an Islamic bond is structured such that the investor funds the borrower’s asset and receives regular rent payments until the contract matures, at which point the borrower buys back the asset.

-

3.

Islamic bonds may not take advantage of interest-rate movements. However, critics have pointed out that the profit of some Islamic bonds is tied to LIBOR or other interest rates (Tariq & Dar, 2007).

-

4.

For example, see Akhtar and Jahromi (2017b) for an overview of these rules. The difference between Islamic stock indices and socially responsible conventional stock indices is that Islamic stock indices also exclude conventional financial institutions and firms with high levels of debt, cash and interest-bearing securities or receivables. This creates entirely different risk and return profiles.

-

5.

Further information on data sources and on our country groupings is given in Table 10 in Appendix A.

-

6.

We also estimate these regressions without the HML and SMB factors, and get similar results. We source the factors from the Ken French library: http://mba.tuck.dartmouth.edu/pages/faculty/ken.french/index.html.

-

7.

This is in line with the literature. Returns and volatility linkages increase in periods of stock market uncertainty, crises, and crashes (e.g., Aggarwal, Inclan, & Leal, 1999).

-

8.

We also estimate these cross-country linkages using squared returns. Results are similar to absolute returns and available upon request. To account for differences in time zones, we use the Cohen, Hawawini, Maier, Schwartz, and Whitcomb (1983) procedure to adjust return covariance matrices for autocorrelation and cross-correlation. We choose lag l = 1. Using this approach, the estimated covariance matrix \(\hat{C}\) is equal to the sum of the contemporaneous estimate and all the lagged estimates, such that \(\hat{C} = \hat{C}_{t,t} + \hat{C}_{t,t - 1} + \hat{C}_{t - 1,t}\).

-

9.

In additional analysis we break down the sample by country type and find that the estimated coefficients of the Islamic dummy variables are negative across samples (Tables B.8 and B.9 in online Appendix B). However, the difference by country type is not statistically significant when we include interaction terms between the Islamic asset and the Islamic country variables in our main regression (results are not reported). This suggests that our results hold in both Islamic and in non-Islamic countries.

-

10.

This analysis involves cross-sectional logit regressions where the outcome variable is whether we observe benefits of diversification with Islamic assets, and we include country-level explanatory variables from the list in Table 8 in Appendix A. Results are available upon request.

-

11.

There are usually stronger diversification benefits in absolute terms (percentage point differences) from including Islamic assets in the portfolio during the crisis period. This can be attributed to the overall larger volatilities and volatility linkages experienced during crises. Once we account for that by expressing differences in volatility linkages in relative terms (percentage differences) in Panels C and D of Table C.14, diversification benefits from Islamic assets are relatively higher during non-crisis periods compared to crisis periods.

-

12.

We perform additional robustness checks for sub-samples of countries for which we have the available data, to verify that the following do not affect our main results: (i) extending the time period back to 31 December 1999 or May 31, 2005; (ii) using alternative bond and money market indices; and (iii) using alternative stock indices, namely replacing standard stock indices (i.e., mid-cap and large-cap firms) with other combinations of large-cap, mid-cap, and small-cap stock indices. Details are provided in Table C.17 in online Appendix C, and results are presented in Tables C.18–C.20 in online Appendix C.

-

13.

The overall results in Table 1 do not change whether differences are expressed in US dollars or in local currency. For example, the difference term "C Stock and C Govt Bond – IS Stock and C Govt Bond” is 0.0261 in US dollars versus 0.0254 in local currency in Panel A, and 0.0272 in US dollars versus 0.0260 in local currency in Panel B.

-

14.

There are no reported coefficients and statistical tests for the difference “C Stock and C Corp Bond - C Stock and IS Corp Bond” using the stochastic volatility model in GMM because there are only two observations in this category. We lose observations under the GMM method (and partially the Kalman filter estimates which rely on estimates from GMM) because the minimization does not always converge given that we have about 50 moment conditions and a relatively short sample period of 3 years.

-

15.

We find consistent results when we sub-divide the medium-term into frequency bands \(\left( {\frac{2}{21}\pi ,\;\frac{2}{5}\pi } \right)\) for cycles between a week and a month, into frequency bands \(\left( {\frac{1}{130}\pi ,\;\frac{2}{21}\pi } \right)\) for cycles between a month and a year, and for dynamic correlations that are estimated around 1-month cycles \(\left( {\frac{2}{21}\pi } \right)\) and one week cycles \(\left( {\frac{2}{5}\pi } \right)\).

REFERENCES

Acemoglu, D., Ozdaglar, A., & Tahbaz-Salehi, A. 2015. Systemic risk and stability in financial networks. American Economic Review, 105(2): 564–608.

Aggarwal, R., Inclan, C., & Leal, R. 1999. Volatility in emerging stock markets. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 34(1): 33–55.

Ahmed, W. M. A. 2018. How do Islamic versus conventional equity markets react to political risk? Dynamic panel evidence. International Economics, 156: 284–304.

Aït-Sahalia, Y., Myckland, P., & Zhang, L. 2011. Ultra high frequency volatility estimation with dependent microstructure noise. Journal of Econometrics, 160(1): 190–203.

Akhtar, S., Akhtar, F., Jahromi, M., & John, K. 2017. Impact of interest rate surprises on Islamic and conventional stocks and bonds. Journal of International Money and Finance, 79: 218–231.

Akhtar, S., & Jahromi, M. 2017a. Impact of the global financial crisis on Islamic and conventional stocks and bonds. Accounting and Finance, 57(3): 623–655.

Akhtar, S., & Jahromi, M. 2017b. Risk, return and mean-variance efficiency of Islamic and non-Islamic stocks: Evidence from a unique Malaysian data set. Accounting and Finance, 57(1): 3–46.

Alam, N., Duygun, M., & Ariss, R. T. 2016. Green sukuk: an innovation in Islamic capital markets. In A. Dorsman, Ö. Arslan Ayaydin, & M. B. Karan (Eds.), Energy and finance: Sustainability in the energy industry: 167–185. Springer.

Al-Shamali, A., Irani, Z., Haffar, M., Al-Shamali, S., & Al-Shamali, F. 2021. The influence of Islamic Work Ethic on employees’ responses to change in Kuwaiti Islamic banks. International Business Review, 30(5): 101817.

Andersen, T. 1996. Return volatility and trading volume: An information flow interpretation of stochastic volatility. Journal of Finance, 51(1): 169–204.

Barillas, F., & Shanken, J. 2017. Which alpha? Review of Financial Studies, 30(4): 1316–1338.

Bartram, S. M. 2019. Corporate hedging and speculation with derivatives. Journal of Corporate Finance, 57: 9–34.

Bauwens, L., & Otranto, E. 2016. Modeling the dependence of conditional correlations on market volatility. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics, 34(2): 254–268.

Beck, T., Senbet, L., & Simbanegavi, W. 2015. Financial inclusion and innovation in Africa: An overview. Journal of African Economies, 24(1): 3–11.

Bekaert, G., & Urias, M. S. 1996. Diversification, integration and emerging market closed-end funds. Journal of Finance, 51(3): 835–869.

Bollerslev, T., Chou, R. Y., & Kroner, K. 1992. ARCH modelling in finance: A review of the theory and empirical evidence. Journal of Econometrics, 52(1–2): 5–59.

Cappiello, L., Engle, R. F., & Sheppard, K. 2006. Asymmetric dynamics in the correlations of global equity and bond returns. Journal of Financial Econometrics, 4(4): 537–572.

Chimenson, D., Tung, R. L., Panibratov, A., & Fang, T. 2022. The paradox and change of Russian cultural values. International Business Review, 31(3): 101944.

Cohen, K. J., Hawawini, G. A., Maier, S. F., Schwartz, R. A., & Whitcomb, D. K. 1983. Friction in the trading process and the estimation of systematic risk. Journal of Financial Economics, 12(2): 263–278.

Croux, C., Forni, M., & Reichlin, L. 2001. A measure of comovement for economic variables: Theory and empirics. Review of Economics and Statistics, 83(2): 232–241.

De Jong, F., & De Roon, F. A. 2005. Time-varying market integration and expected returns in emerging markets. Journal of Financial Economics, 78(3): 583–613.

Domat, C. 2020. Islamic finance: Just for Muslim-majority nations? https://www.gfmag.com/topics/blogs/islamic-finance-just-muslimmajority-nations.

Doukas, J. A., & Kan, B. K. 2006. Does global diversification destroy firm value. Journal of International Business Studies, 37: 352–371.

Errunza, V. R. 1977. Gain from portfolio diversification into less developed countries’ securities. Journal of International Business Studies, 8(2): 83–100.

Errunza, V. R., & Senbet, L. W. 1981. The effects of international operations on the market value of the firm: Theory and evidence. Journal of Finance, 36(2): 401–417.