Abstract

This paper presents a review and critique of the 20-year-old literature on institutional distance, which has greatly proliferated. We start with a discussion of the three institutional perspectives that have served as a theoretical foundation for this construct: organizational institutionalism, institutional economics, and comparative institutionalism. We use this as an organizing framework to describe the different ways in which institutional distance has been conceptualized and measured, and to analyze the most common organizational outcomes that have been linked to institutional distance, as well as the proposed explanatory mechanisms of those effects. We substantiate our qualitative review with a meta-analysis, which synthesizes the main findings in this area of research. Building on our review and previous critical work, we note key ambiguities in the institutional distance literature related to underlying theoretical perspectives and associated mechanisms, distance versus profile effects, and measurement. We conclude with actionable recommendations for improving institutional distance research.

Résumé

Cet article présente une revue et une critique de la littérature de 20 années sur la distance institutionnelle qui s’est beaucoup développée. Nous commençons par une analyse des trois perspectives institutionnelles qui ont servi de fondement théorique à cette construction : l’institutionnalisme organisationnel, l’économie institutionnelle et l’institutionnalisme comparatif. Nous nous en servons comme cadre d’organisation pour décrire les différentes façons dont la distance institutionnelle a été conceptualisée et mesurée, et pour analyser les résultats organisationnels les plus courants qui sont liés à la distance institutionnelle, ainsi que les mécanismes explicatifs proposés concernant ces effets. Nous étayons notre examen qualitatif par une méta-analyse qui synthétise les principales contributions dans ce domaine de recherche. En nous fondant sur notre revue de la littérature et les travaux critiques antérieurs, nous relevons des ambiguïtés clés dans les recherches portant sur la distance institutionnelle en ce qui concerne les perspectives théoriques sous-jacentes et les mécanismes connexes, les effets de la distance par rapport au profil, et les mesures associées. En conclusion, nous formulons des recommandations pratiques pour améliorer la recherche sur la distance institutionnelle.

Resumen

Este artículo presenta una revisión y una crítica de la literatura de 20 años sobre la distancia institucional, la cual ha proliferado enormemente. Comenzamos con una discusión de las tres perspectivas institucionales que han servido como la fundamentación teórica de este constructo – institucionalismo organizacional, economía institucional, e institucionalismo comparativo. Usamos este como un marco organizador para describir las diferentes maneras en las cuales la distancia institucional ha sido conceptualizada y medida, y para analizar los resultados organizacionales más comunes que han sido vinculados a la distancia institucional, así como también los mecanismos explicativos propuestos de estos efectos. Corroboramos nuestra revisión cualitativa con un meta-análisis, el cual sintetiza los mayores hallazgos en esta área de investigación. Basándonos en nuestra revisión y el trabajo previo crítico, notamos ambigüedades clave en la literatura de distancia institucional en relación a las perspectivas teóricas subyacentes y los mecanismos asociados, los efectos de la distancia versus los efectos del perfil, y la medición. Concluimos con recomendaciones viables para mejorar la investigación sobre la distancia institucional.

Resumo

Este artigo apresenta uma revisão e uma crítica da literatura de 20 anos sobre distância institucional, que proliferou bastante. Começamos com uma discussão das três perspectivas institucionais que serviram de base teórica para esse construto - institucionalismo organizacional, economia institucional e institucionalismo comparativo. Utilizamos isso como um modelo organizador para descrever as diferentes maneiras pelas quais distância institucional foi conceitualizada e mensurada, e para analisar os resultados organizacionais mais comuns que foram vinculados a distância institucional, bem como os mecanismos explicativos propostos para esses efeitos. Fundamentamos nossa revisão qualitativa com uma metanálise, que sintetiza os principais achados nessa área de pesquisa. Com base em nossa revisão e em trabalhos críticos anteriores, observamos ambiguidades importantes na literatura sobre distância institucional relacionadas às perspectivas teóricas subjacentes e mecanismos associados, distância versus efeitos de perfil e mensuração. Concluímos com recomendações práticas para melhorar a pesquisa em distância institucional.

摘要

本文对20年来激增了许多的有关制度距离的文献进行综述和评论。我们首先讨论了作为这个概念理论基础的三种制度观点 – 组织制度主义、制度经济学和比较制度主义。我们以此为组织框架, 描述了制度距离被概念化和度量的不同方式, 并分析了与制度距离相关的最常见的组织结果, 以及对这些影响的解释机制。我们通过汇总分析证实了我们的定性文献综述, 该分析综合了该研究领域的主要发现。在我们的文献综述和先前的关键工作的基础上, 我们注意到制度距离文献中与基本理论观点及相关机制、距离对比轮廓的效应、以及度量相关的主要歧义。

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

International business scholars have long recognized the importance of national context and contextual embeddedness of organizations (Westney, 1993), and have studied the impact of “distance”, i.e., cross-country contextual differences, on firms’ strategies, management practices, and organizational outcomes (e.g., Johanson & Vahlne, 1977; Kogut & Singh, 1988; Kostova & Zaheer, 1999). Given that conducting business across borders is a defining characteristic of multinational companies (MNCs), some have concluded that “essentially, international management is management of distance” (Zaheer et al., 2012: 19). Reflecting the different domains of national context, scholars have examined different types of distance including cultural (e.g., Beugelsdijk, Kostova, Kunst, Spadafora, & van Essen, 2018b; Kirkman, Lowe, & Gibson, 2006, 2017; Kogut & Singh, 1988; Shenkar, Luo, & Yeheskel, 2008), psychic (e.g., Dow & Karunaratna, 2006; Johanson & Vahlne, 1977), geographic (e.g., Beugelsdijk & Mudambi, 2013; Hakanson & Ambos, 2010), economic (e.g., Ghemawat, 2001), and others.

Since its introduction in the literature in the mid-1990s (Kostova, 1996, 1997), the construct of institutional distance has gained prominence in international business research (e.g., Aguilera & Grøgaard, 2019; Bae & Salomon, 2010; Berry, Guillén, & Zhou, 2010; Beugelsdijk, Ambos, & Nell, 2018a; Fortwengel, 2017; Jackson & Deeg, 2019; Zaheer, Schomaker, & Nachum, 2012). Broadly defined as the difference between the institutional profiles of two countries, typically the home and the host country of an MNC (Kostova, 1996), institutional distance has quickly become one of the most widely used types of distance in this research. The interest in institutional distance has been triggered by the rapid expansion of MNCs to markets that are substantially different from their home countries. With increased globalization, developed country MNCs are finding themselves in unfamiliar territories, as they enter emerging markets and developing and transition economies. These markets are characterized by uncertainty and ambiguity, high economic and political risks, unusual complexity, and major deficiencies, collectively termed “institutional voids.” (Khanna, Palepu, & Sinha, 2005). Likewise, a growing number of emerging market MNCs are aggressively expanding to the most competitive markets in the world, which often operate under very different economic systems and institutional rules (Fortune, 2018). Even if they do not directly invest abroad, many companies are participants in global production networks, which indirectly expose them to multiple foreign environments (Levy, 2008). Thus, understanding cross-country differences and their impact on business, and learning how to navigate successfully across diverse environments have become front-and-center tasks for global managers.

As argued in the original research introducing the institutional lens as an alternative to culture (Kostova, 1996, 1997), institutional distance provides a broader view of national contexts, encompassing not only cultural but also regulatory and cognitive elements (Kostova, 1996; Scott, 1991). Institutional distance also allows the capturing of the dynamic aspects of context, reflecting important institutional changes in countries throughout the world. Theoretically, it can be more precise in its predictions than cultural distance if analyzed with regard to a specific issue, for example, quality management (Kostova, 1996) or entrepreneurship (Busenitz, Gomez, & Spencer, 2000). Over time, this work has been enriched by many contributions that have further developed the construct, expanding and modifying its conceptualization, introducing new ways of operationalization and measurement, and incorporating it in hundreds of studies of different international business phenomena (e.g., Bae & Solomon, 2010; Berry et al., 2010; Gaur & Lu, 2007; Gaur, Delios, & Singh, 2007; Xu, Pan & Beamish, 2004).

The proliferation of definitions, operationalizations, and proposed theoretical effects, however, has also raised concerns about the tightness and rigor of this construct and the comparability of institutional distance research across studies. A number of scholars have been troubled by such somewhat undisciplined diversity and the potential problems it might create, and have offered ideas of how to strengthen this research, conceptually and methodologically (Bae & Salomon, 2010; Berry et al., 2010; Beugelsdijk et al., 2018a; Fortwengel, 2017; Hotho & Pedersen, 2012; Philips, Tracey, & Karra, 2009; Zaheer et al., 2012). We too recognize that, at the extreme, such a broad and unscripted approach may create the sense that institutional distance is a “catch all” construct simply substituting for country. At this point in time and in this context, it would be beneficial to have a critical look at institutional distance research and to try to streamline its many different strands and approaches into a more cohesive view.

Our objectives in this review paper are three-fold. The first it to take stock of the growing literature on institutional distance by identifying the major institutional theory traditions employed, the ways in which institutional distance has been conceptualized and measured, and the theoretical mechanisms proposed. The second is to synthesize and analyze this literature by identifying robust findings on the impact of institutional distance on various organizational outcomes, including location choice, entry mode, performance, and others, as well as gaps and problematic areas in this work. The third is to offer insights and specific actionable recommendations for a more disciplined and rigorous approach to institutional distance research in the future. We combine several approaches: a comprehensive review of the literature, rigorous meta-analysis of existing empirical research, and analysis and insights. The paper is based on a preliminary identification of over 1000 studies that have used the construct of institutional distance (published between 2002 and 2018), followed by an in-depth review of a representative sample of 171 studies, and a meta-analysis of 137 empirical papers from this sample.

Theoretical perspectives in institutional distance research

The construct of institutional distance is rooted in the notion of contextual embeddedness of organizations, which recognizes the “embeddedness of economic activity in wider social structures” (Dacin, Ventresca, & Beal, 1999: 318). Originating in political economy and economic sociology, the concept of embeddedness was social scientists’ response to both the “under-socialized” economic views of organizations that focused exclusively on resources and transactions, while ignoring the social aspect of markets, and the “over-socialized” views that studied social processes without sufficient consideration of economic relations (Parsons, 1960; Polanyi, 1944). As Granovetter (1985) suggests, economic activity occurs in on-going patterns of social relations: “All market processes are amenable to sociological analysis and …such analysis reveals central, not peripheral features of these processes” (Granovetter, 1985: 505). Social structures impact economic activity through a variety of mechanisms: structural (social ties between social actors); cognitive (symbolic representations and frameworks of meaning that affect interpretation and sense-making by economic actors); cultural (shared understandings, norms, belief systems, and logics); and political (societal power structures and the distribution of resources and opportunities) (Dacin et al., 1999; Zucker, 1987).

Institutional theory in particular studies the embeddedness of organizations in institutional environments (Hall & Soskice, 2001; Whitley, 1999; Jackson & Deeg, 2008, 2019; North, 1990; Scott, 1995, 2014). While institutions and institutional embeddedness operate at different levels of analysis—from global, to field, to organization, to industry, to interpersonal (Scott, 1995, 2014)—the primary level employed in international business research is the nation state. The central idea in institutional distance research is that companies doing business across national borders are embedded and exposed to multiple and different institutional environments in their home and host countries, and, as a result, face unique difficulties and risks (Kostova, 1999). The extent of such differences (i.e., institutional distance) determines the specific challenges faced in each set of conditions and affects companies’ strategic and managerial decisions and actions.

Three Schools of Thought

Institutional theory is rich and multifaceted (Aguilera & Grøgaard, 2019). As a result, institutions, institutional embeddedness, and institutional distance have been defined in a variety of ways, depending on the particular institutional perspective taken. Following Hotho and Pedersen’s insightful framework (2012), we distinguish between three strands of institutional theory: organizational institutionalism, institutional economics, and comparative institutionalism, which propose different conceptualizations of institutions, institutional distance, and the mechanisms by which it affects various outcomes. Institutional distance work has drawn from all these perspectives, sometimes explicitly specifying the perspective followed, and sometimes without a clear reference. This, we believe, has led to some confusion and ambiguity, which we will discuss in the critique section of the paper.

Organizational institutionalism is rooted in sociology. Here, institutions are viewed as relatively stable social structures composed of regulative, cultural-cognitive, and normative elements that, together with associated activities and resources, provide stability and meaning to social life (Meyer & Rowan, 1977; Powell & DiMaggio, 1991; Selznick, 1957; Scott, 1995). Institutions determine not only what is legal but also “legitimate”, i.e., acceptable and approved way of conducting certain functions in a particular society; under pressures for legitimacy in the broader institutional environment, organizations belonging to the same organizational field become similar, or isomorphic, with each other as they adopt those legitimate structures and practices, which over time assume a “taken for granted” status (Meyer & Rowan, 1977; Powell & DiMaggio, 1991; Selznick, 1957; Scott, 1995).

The original definition of institutional distance (Kostova, 1996) drew from this perspective, specifically based on Scott’s (1995) “three pillars” conceptualization of institutions: regulatory (rules and laws that exist to ensure stability and order in societies), cognitive (established cognitive structures in society that are taken for granted), and normative (domain of social values, cultures, and norms). Accordingly, institutional distance between two countries was defined as the difference between their regulatory, cognitive, and normative institutions (Kostova, 1996). The main explanation of why institutional distance matters here is that different countries have different institutions and, therefore, different ways of conducting certain functions that are viewed as “legitimate”. When companies do business across borders, they face a challenge to not only learn new ways of conducting certain functions but also to satisfy multiple, different, and possibly conflicting, legitimacy requirements and expectations. This creates tensions externally, between the organization and its external legitimating environment (e.g., a particular host country), and internally, between organizational units located in different countries and therefore abiding by different institutional rules (Kostova & Zaheer, 1999).

Institutional economics has its roots in the economics discipline. Institutions are defined as “the humanly devised constraints that structure human interaction” and are categorized into formal (rules, laws, constitutions) and informal (norms of behavior, conventions, and self-imposed codes of conduct) (North, 1990: 3). Formal institutions determine the rules that govern economic activity and thus reduce uncertainty, risk, and transaction costs. Informal institutions, too, help coordinate economic action and become particularly important in the absence of strong formal market institutions. Accordingly, scholars have considered two types of institutional distance: formal and informal. As an example, Abdi and Aulakh (2012) distinguish between formal institutional distance (i.e., differences between the formal institutions such as existence and enforcement of market supporting rules) and informal institutional distance (i.e., differences between the shared norms, values, practices, and frames of interpretation in two countries). Estrin, Baghdasaeyan, and Meyer (2009) view formal institutional distance as concerning laws and rules that influence business strategies and operations, and informal institutional distance concerning rules embedded in values, norms and beliefs. Slangen and Beugelsdijk (2010) use the distinction between formal and informal institutional distance to show how differences in formal governance regulations and informal cultures affect market-seeking and efficiency-seeking foreign direct investment in different ways. Notably, informal distance tends to be more loosely defined in this research tradition: for example, Zhu, Xia, and Makino (2015) introduce language differences as part of informal distance.

Although both organizational institutionalism and institutional economics suggest that institutional distance leads to higher costs of doing business abroad (e.g., Dikova, Sahib, & van Witteloostuijn, 2010; Henisz & Williamson, 1999), there is a fundamental difference between the proposed explanatory mechanisms. Organizational institutionalism emphasizes the legitimacy mechanism whereby, in familiar institutional settings (e.g., their home country), organizations understand the existing institutional order and can more easily comply with the legitimacy requirements and expectations, while, in unfamiliar, particularly “distant”, environments (e.g., host country), companies have limited knowledge and understanding of how things are and should be done to establish and maintain an effective and legitimate operation (Kostova & Zaheer, 1999; Eden & Miller, 2004; Xu & Shenkar, 2002). There is also the risk of internal tensions between organizational units residing in different countries, as they try to work with the external institutional arrangements in their respective country (Kostova & Roth, 2002). Furthermore, there is an additional difficulty resulting from the different treatment that foreign companies get from local actors due to their “foreignness” (e.g., Mezias, 2002). In summary, institutional distance here leads to higher costs and risks because of lack of understanding of the institutional order, inability to simultaneously adjust to institutional requirements in multiple countries, challenges in establishing external legitimacy, and increased internal and external complexity.

The emphasis in institutional economics is not on legitimacy, liability of foreignness, and adaptation, but on the differing quality of institutional environments between countries, and on the different degree to which the existing institutions in a given country support effective economic activity and coordination between economic actors. There is a “sign” to the distance in this perspective. The increase in transaction costs depends not only on the countries involved but also on the direction of foreign expansion (Trapczynski & Banalieva, 2016). Less developed formal institutions in a given country tend to increase transaction costs due to the ineffectiveness of market mechanisms of economic coordination. They also imply more opaque and unstable institutional rules that are difficult to make sense of and follow (Khanna & Palepu, 1997, 2000). The institution-related challenges are greater for companies moving from a more to a less institutionally developed environment than the other way around. While at home such companies are generally used to relying on formal institutions to carry out their economic activities, expanding into less developed host countries requires new understanding of the role of informal institutions, and learning new strategies and tactics for functioning under such conditions. Institutional distance is also an issue in the opposite direction, when companies are moving from less to more institutionally developed environments. In this case, the challenges are more related to the organization’s ability to learn how to function under stricter and more mature institutional frameworks without the “help” of informality. In summary, distance in institutional economics has a differential effect, depending on the home and host countries’ institutional quality, the specific sources of the related costs and risks, the types of organizational outcomes that might be affected the most, and the possible remedies for overcoming the challenges of distance.

Comparative institutionalism emphasizes the system of interdependent institutional arrangements in different areas of socio-economic life in a given country (e.g., economic models, legal frameworks, educational systems, national innovation systems, levels of development, role of the state, labor). This theory proposes typologies of national institutional systems, such as the liberal market economy or the coordinated market economy (Hall & Soskice, 2001; LaPorta, Lopez-de-Silanes, Shleifer, & Vishny, 1998; Nelson & Rosenberg, 1993; Whitley, 1999). Institutions reflecting the different facets of a country’s institutional environment are seen as complementary and in combination with each other. They exist in national configurations that generate a particular systematic logic of economic action and reflect the overall institutional “character” of the nation (Jackson & Deeg, 2008, 2019).

In the context of cross-country diversity, this perspective is distinct from the previous two, in that conceptually it captures difference more than distance. Both organizational institutionalism and institutional economics conceive of home- and host-country diversity in terms of linear differences between discrete institutional parameters or variables (Jackson & Deeg, 2008, 2019). In contrast, the emphasis in comparative institutionalism is on the differences between configurations of types of cases at the country level (Jackson & Deeg, 2008, 2019) or between institutional clusters as illustrated by the term varieties of capitalism (Judge, Fainschmidt, & Lee Brown III, 2014; Hotho, 2013). The impact of institutional differences from this perspective is discussed in terms of the overall “fit” between “firm-specific resources” and “the particular resource environments of a host country” (Jackson & Deeg, 2008: 543). Recognizing the interdependence between the various institutional aspects is an appealing advantage of this approach as it allows the capturing of cross-country “differences not of degree but of kind” (Jackson & Deeg, 2019: 5). At the same time, it is a departure from traditional treatment of institutional distance and presents some theoretical and empirical challenges to distance scholars.

Although not explicitly stated in their paper, we view Berry et al.’s (2010) work as an attempt to bridge traditional comparative institutionalism with distance research. To do that, similar to the comparativist tradition, the authors conceptualize institutions as a system of arrangements in nine different facets of a country’s socio-economic life that logically hang together: politics, finance, economy, demography, administration, culture, knowledge, global connectedness, and geography. Unlike comparative institutionalism, though, they do not collapse the construct to an institutional “variety” or “type”. Instead, they suggest theorizing at the dimension level to capture possible differential effects. At the same time, to stay truer to the configurational approach, they depart from traditional methods of multidimensional operationalizations (e.g., Euclidean distance), proposing instead the Mahalanobis method, which accounts for the interdependence between the different institutional dimensions (Berry et al., 2010). Overall, Berry et al.’s (2010) work has been well received, especially for the proposed Mahalanobis methodology (e.g., Kang, Lee, & Ghauri, 2017; Lindner, Muellner, & Puck, 2016). However, the key comparative institutional theoretical ideas behind Berry et al.’s (2010) work have not been sufficiently developed and employed in subsequent IB research.

Use of the Three Perspectives

For a more accurate assessment of the salience of the different institutional schools of thought in distance research, we relied on the subsample of 137 empirical studies included in our meta-analysis. We evaluated the perspective used by each paper in our sample: that is, each of the 137 empirical studies was classified in one or two of the above traditions based on the primary theoretical mechanisms discussed and hypothesized (see the “Appendix” for more details). Although the grounding of the research in a particular theoretical tradition was not always clear and/or explicit, and in many cases authors mixed multiple strands of institutional theory, we were able to reach a consensus on this question through a rigorous coding procedure. The coding was carried out by three independent scholars, followed by additional deliberations in case of disagreement. Table 1 provides an overview of institutional distance studies that have their theoretical grounding in the three institutional perspectives.

As seen from the table, the three perspectives have not been equally represented in this literature. It should be noted that, of the 137 studies in the sample, institutional distance was part of the main model in 101 papers. The other 36 studies used institutional distance as a control variable; thus authors were less deliberate in clearly positioning their discussion of distance in any particular theoretical frame. Also, 13 of the 101 studies that examined institutional distance used none of the three institutional theories discussed above, employing instead other theoretical lenses, for example, learning theory (e.g., Perkins, 2014; Powell & Rhee, 2016).

Overall, organizational institutionalism has been the predominant perspective in this literature (38 of the 101 papers in our sample), followed by institutional economics (28 of the 101 papers), and an eclectic combination of different perspectives, usually organizational institutionalism and institutional economics (22 of the 101 studies). Comparative institutionalism, while increasingly used in international business research, has hardly been applied as a theoretical lens in distance literature. Hence, it is not included as a stand-alone perspective in Table 1.

In our view, organizational institutionalism has received the most attention, partly because it was the first to be used in institutional distance research (Kostova, 1996; Kostova & Roth, 2002; Busenitz et al., 2000). In addition, it provides a broad framework for studying institutional context and cross-country differences, giving researchers many choices to pick country-level variables that reflect various aspects of national environments and suit their research questions, ranging from laws and regulations, to cognitive structures and social knowledge, to social norms and cultural values. This approach allows the examination of institutional effects on a wide range of outcomes related to MNC strategies and organizational actions. The possibility of tailoring the application to a specific issue by selecting relevant institutional parameters further increases the capacity to explain outcomes of interest. Another facilitating factor for the use of organizational institutionalism is the growing availability of reliable, accessible, and often longitudinal secondary data, measuring various institutional facets provided by the World Bank and other institutions (e.g., Heritage Foundation). As will be discussed below, the easy access to data on these dimensions appears to be an important factor in the more common use of those institutional dimensions, for which there is an abundance of data.

The use of the institutional economics perspective has increased steadily, especially in the last few years: 21 of 28 papers in this camp have been published in the last 5 years. We attribute this to the rise of emerging markets and their role in international business, and to the growing research devoted to studying that context, which brings forth the issues of quality of institutional environments, “institutional voids”, and substitutability of formal and informal institutions (e.g., Khanna et al., 2005; Peng, Wang, & Jiang, 2008). Institutional economics is well suited to studying those contexts. In addition, institutional economics applications have also benefited from the availability of secondary institutional data that can be used to quantify formal and informal institutions, for example, World Bank Governance Indicators, the Economic Freedom Index, and the Global Competitiveness Index (see Table 3 below). Overall, in later work, we find that organizational institutionalism has been gradually supplemented by institutional economics. While the volume of papers applying organizational institutionalism has been relatively stable over time, its relative share in all distance research has gone down from 33% from 2002 to 2014 to 25% in the period after 2014.

The use of comparative institutionalism in distance research is rather limited, despite the growing interest of international business scholars in this perspective (Aguilera & Grøgaard, 2019; Jackson & Deeg, 2019). There are a few studies that draw on Berry et al. (2010) and apply the Mahalanobis methodology for calculating institutional distance. They vary widely, with the type and number of institutional dimensions considered ranging from the full set of nine (Kang, Lee, & Ghauri, 2017) to a subset of a selected few or even a single dimension (e.g., Pinto, Ferreira, Falaster, Fleury, & Fleury, 2017). Lindner, Muellner, and Puck’s (2016) study, which uses four of the nine dimensions related to the regulatory and normative domains, exemplifies the typical application. There are also studies that select one dimension, mostly administrative distance (e.g., Ahrens et al., 2018; Brown, Yaşar, & Rasheed, 2018; Jung & Lee, 2018) or various subsets as control variables (e.g., Schwens, Zapkau, Brouthers, & Hollender, 2018; Valentino, Schmitt, Koch, & Nell, 2018). None of these studies, however, are clearly positioned in the comparative institutionalism theoretical tradition, because they do not theorize at the level of the configuration. Theoretically, it is difficult to link the notion of distance with the configurational idea of comparative institutionalism, which is conceptually closer to difference rather than distance. Shifting from difference to distance is not as easy as the similar wording might make it appear. Fortwengel (2017) is a recent attempt to strengthen the theoretical underpinnings of comparative institutionalism in distance research. He proposes four characteristics of institutional configurations—coordination, strength, thickness, and resources—and conceptualizes distance as the difference between these characteristics. Overall, the application of this perspective in distance research is in its infancy and raises serious questions about the appropriateness of comparative institutionalism in this line of work. Due to the small number of associated studies, we could not include them in the meta-analysis and Table 1.

Methodological approaches in institutional distance research

In addition to the diversity in theorizing on institutional distance, this literature is also characterized by diversity in methodological approaches. Below is a brief review of the most common approaches employed.

Operationalization

Table 1 shows that operationalizations vary, generally depending on the particular institutional perspective employed. Most studies take a multidimensional approach. Research following organizational institutionalism typically utilizes Scott’s (1995) “three pillars” of regulatory, cognitive, and normative institutions, and constructs distance measures accordingly. Many papers use a separate measure for each of the three distances—regulatory, cognitive, and normative distances (e.g., He, Brouthers, & Filatothev, 2013)—but some collapse normative and cognitive distances and construct one measure to capture both of them together (e.g., Gaur & Lu, 2007; Jensen & Szulanski, 2004). A number of papers focus on the regulatory and normative distances only (e.g., Ang, Benischke, & Doh, 2015; Madsen, 2009), and construct separate measures for each of them (Gaur & Lu, 2007; Gaur et al., 2007; Xu et al., 2004). Among the three distances, regulatory distance is the one most frequently studied. Scott himself has always presented the pillars as analytic conceptual tools, while explicitly acknowledging that the elements associated with the pillars are often jointly at work and may change over time (Scott, 2014).

Research grounded in institutional economics distinguishes between formal and informal institutions (North, 1990, 1991) and constructs separate distance measures for each of them (e.g., Abdi & Aulakh, 2012; Dikova et al., 2010; Estrin et al., 2009). Some papers examine only the effects of formal institutional distance (e.g., Zhou, Xie, & Wang, 2016) or informal institutional distance (e.g., Sartor & Beamish, 2014; Schwens, Eiche, & Kabst, 2011) on their outcome variables, and thus construct one measure for that particular type.

There are exceptions to the multidimensional operationalization of institutions and institutional distance. As seen in Table 1, some papers take more of a reductionist approach and measure institutional distance as a unidimensional construct (e.g., Dellestrand & Kappen, 2012; Lahiri, Elango, & Kundu, 2014). Most of these studies use institutional distance as a control (27 of the 72 studies), although there are a number of papers where institutional distance is a main variable that follows the same unidimensional approach. Twelve of the 38 studies classified as organizational institutionalist, and 14 of the 28 rooted in institutional economics, take a unidimensional approach. In most of these papers, the authors recognize the multidimensionality of the construct in their theoretical discussions, but reduce it to one dimension when it comes to operationalization, usually choosing an institutional variable that is easy to explain and for which there are readily available data.

For example, in their study of cross-border acquisitions, Lahiri et al. (2014) discuss both formal and informal institutions when theorizing on the institutional environment and institutional distance, but use only formal institutions to represent institutional distance, stating that “institutional distance measures the difference in the development of formal institutions between acquirer and target nation”. Similarly, Gubbi, Aulakh, Ray, Sarkar, & Chittoor (2010) state that “institutional distance captures the differences in normative, regulative, and cognitive constructs between two economies”, but operationalize it as the strength of market-supporting institutions and measure it through a single index. Zhou et al. (2016) also use a single index to measure institutional distance, focusing on business-related laws and regulation, which they suggest reflect the ‘‘rules of the game in a society’’. Hence, a significant proportion of the papers employing organizational institutionalism do not sufficiently leverage the three pillars discussed by Scott (1995). Even when they use Scott’s framework in the theoretical development, they rarely utilize the three aspects of institutional distance in operationalizing and measuring the construct. This is also common in papers grounded in institutional economics, which either use a generic term of institutional distance without specifying the nature of the different institutions, or, even when they do so theoretically, settle on using only one type of institutions empirically, usually formal institutions.

Measurement

Measures of institutional distance are quite diverse. They vary between multidimensional collapsed into single-index (e.g., Pinto et al., 2017), single-index (e.g., Somaya & McDaniel, 2012), absolute difference (e.g., Liou, Chao, & Yang, 2016; Liou, Chao, & Ellstrand, 2017), weighted absolute-difference (Chao & Kumar, 2010), Euclidean distance (e.g., Gaur & Lu, 2007), Mahalanobis distance (e.g., Berry et al., 2010; He et al., 2013), positive and negative distance measures (e.g., Trapczynski & Banalieva, 2016), and other variations. Table 2 presents a summary of the data sources used for the different distance operationalizations.

Initially, institutional distance (grounded in organizational institutionalism) was measured through a specifically constructed survey instrument that captured its three dimensions, regulatory, cognitive, and normative (Kostova, 1996, 1997). In addition to capturing all three pillars, this approach was argued to be superior to alternative country-level measures because the survey was anchored in a particular issue domain: quality and quality management, assessing the regulations, social knowledge, and cultural norms related to the specific issue of quality. The same approach was followed by other scholars who developed surveys to measure the favorability of institutional environments with regard to other issues, for example, entrepreneurship (Busenitz et al., 2000) and market orientation (Kirca, Jayachandran, & Bearden, 2005). The issue-specific approach is consistent with organizational institutionalism, in particular with the notion of organizational field, suggesting that countries might be similar in some domains of economic and social life (e.g., rule-of-law), but significantly different in other aspects (e.g., environmental protection). Measuring institutions and institutional distance by issue provides a more potent assessment of the institutional differences that really matter for the particular question under investigation. The alternative of using general country-level measures such as regulatory quality or rule of law, while meaningful for certain questions, may be less informative for other specific research questions (Kostova, 1997). The subsequent literature has departed from the domain-specific and survey-based measurement approach, using instead a variety of more generic country-level measures based on secondary data to capture whatever institutional dimensions are hypothesized in the theoretical models. This shift can partly be explained by the increased availability and quality of such data.

In the organizational institutionalism tradition, regulatory distance is most commonly measured with World Governance Indicators (WGI) (World Bank), the Economic Freedom Index (EFI) (Heritage Foundation), the World Competiveness Yearbook (WCY) (IMD), or the Global Competitiveness Report (GCR) (World Economic Forum). A different set of items from these same databases has been used to measure normative distance. Studies by Gaur and Lu (2007), Gaur et al. (2007) and Xu et al. (2004) have been particularly influential in adopting this approach, as it suggested alternative sets of items from the WCY and the GCR that could be used to measure regulatory and normative distance, respectively. The most glaring gaps in terms of using Scott’s three pillars relate to the cognitive dimension. Many studies skip it altogether, especially when it comes to measurement, and half of those that do provide measures on cognitive distance use Hofstede’s cultural dimensions. For example, Gaur et al. (2007) argue that cultural distance is rooted in the cultural-cognitive dimension of a nation’s institutional environment. Jensen and Szulanski (2004) operationalized institutional distance as cultural distance, and measured it using the Kogut and Singh cultural distance index (1988), arguing that it captures both the cognitive and normative dimensions.

Work in the institutional economics tradition most often uses data from WGI and the EFI. These sources are typical for studies using a unidimensional distance index, and are also commonly used to measure formal institutional distance in two-dimensional operationalizations. Informal distance is measured primarily by Hofstede’s cultural dimensions (Hofstede, 1980, 2001), although there are exceptions where scholars employ alternative cultural frameworks. For example, Estrin et al. (2009) use both Hofstede and GLOBE-based indexes to measure informal institutional distance. It is fair to say that the typical institutional distance study in the institutional economics tradition measures formal distance, using either the WGI or the EFI, and informal distance using Hofstede’s cultural dimensions. The latter is commonly operationalized using the Kogut and Singh index of cultural distance (Kogut & Singh, 1988). Table 3 presents the different measures and sources of data used in institutional distance research.

Concerns

Our analysis of operationalization and measurement of institutional distance suggests several points of attention, if not concern. First, the same data are used to measure institutional variables that belong to different theoretical traditions. In the case of regulatory distance (organizational institutionalism) and formal distance (institutional economics), this is less of a problem given that Scott himself builds this link, referring to North when discussing regulatory distance (Scott, 1995, 2014). However, the interchangeable use of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions in measuring informal (institutional economics) as well as cognitive and normative distance (organizational institutionalism) is more problematic, because it is not true to the conceptual essence of these constructs. Hofstede’s indexes represent cultural value dimensions, while the cognitive institutional aspect is supposed to capture the “taken for granted” habitual ways of doing certain things in a society. An extreme example of how these might be disconnected can be offered around the issue of corruption. Most countries would not view corruption as “the right thing to do” (value judgment), but in many it is “how things get done around here” (cognitive habituality). Even more problematic is the use of cultural indexes to measure informal institutions. In North’s framework, informal institutions are important because they can serve as complements, or, in some cases, as substitutes for weak formal institutions. Thus, the function of informal institutions is to help coordinate economic and social transactions and interactions in a society, especially in the absence of strong formal institutions. Culture, in Hofstede’s framework, has not been conceptualized as either a formal or an informal market coordination mechanism. The level of power distance or masculinity, for example, is not conceptually linked to facilitating economic transactions. Also, in many articles within the organizational institutionalist tradition, regulatory and normative distance have both been measured using a variety of databases. This raises the more fundamental question of whether results obtained for the same dependent variable depend on the particular measure used. As Beugelsdijk et al. (2018a) show, the correlation between distance indexes based on WGI and EFI is low, suggesting that these databases cannot be used interchangeably, thus raising questions on the sensitivity of empirical findings.

Main findings in institutional distance research

A key question in our study concerned the various outcomes that have been linked to institutional distance in research. We identified 20 different outcomes in the full sample of 171 papers. The most investigated outcome is firm performance (e.g., Gaur & Lu, 2007; Lazarova, Peretz, & Fried, 2018; Shirodkar & Konara, 2017). Other frequently examined outcomes include ownership structure (e.g., Ilhan-Nas, Okanb, Tatogluc, Demirbag, Woode, & Glaisterf, 2018; Powell & Rhee, 2016; Xu et al., 2004), location choice (e.g., Madsen, 2009; Romero-Martinez, Garcia, Muina, Chidlow, & Larimo, 2019; Xu & Shenkar, 2002), headquarters–subsidiary relationship (e.g., Dellestrand & Kappen, 2012; Li, Jiang, & Shen, 2016; Valentino et al., 2018), and entry mode (e.g., Brouthers, Brouthers, & Werner, 2008; Ang et al., 2015). Cross-border mergers and acquisitions deal abandonment/completion (e.g., Bhaumika, Owolabib, & Sarmistha, 2018; Dikova et al., 2010), establishment mode/type (e.g., Arslan, Tarba, & Larimo, 2015; Estrin et al., 2009), and cross-border transfer of organizational practices (e.g., Jensen & Szulanski, 2004; Kostova, 1999) have also been studied a few times. Other outcomes have only been examined once or twice, for instance, MNEs’ legitimacy and isomorphism (e.g., Kostova & Zaheer, 1999; Salomon & Wu, 2012). It can therefore be concluded that institutional distance has been employed in a wide variety of studies.

In light of the proliferation of theoretical and methodological approaches discussed above, we were also interested in assessing, to the extent possible, whether particular theoretical perspectives, operationalizations, and measurements are more potent than others in providing insights into certain organizational outcomes. What sources of data seem to be more informative in capturing the effects of institutional distance? Are results sensitive to the use of different measurement methods (e.g., Euclidean vs. Mahalanobis)? In this effort, we supplemented our literature review with a rigorous meta-analysis of the empirical studies in the sample. A total of 137 papers were included, providing sufficient sample size for this technique. A list of these studies can be found in the “Appendix”.

Overall, most of the papers examined the impact of institutional distance on firm performance and internationalization, including different stages of the internationalization process, such as location choice, and entry and establishment mode. To our surprise, in our sample, there were fewer papers (not sufficient for conducting a meta-analysis) that linked institutional distance to management and organizational issues such as transfer of practices or headquarters control (e.g., Kostova & Roth, 2002; Dellestrand & Kappen, 2012) Specifically, of all the statistical relationships included in our meta-analysis, 50% were on performance, closely followed by entry mode (full or partial ownership) (39%). The number of location choice (5%) and establishment mode (greenfield or acquisition) (6%) studies is rather limited. Thus, we could only evaluate the methodological questions with respect to operationalization and measurement in studies on performance and entry mode. For that reason, we present the results for performance and entry mode in the main text, and delegate detailed results on location choice and establishment mode to the “Appendix”.

MNC and Subsidiary Performance

As shown in Table 4, we find that institutional distance generally has a negative effect on firm performance, including almost all types of performance used, i.e., accounting, market, and survival measures. Survival of a foreign market entry experienced the most detrimental effect of institutional distance. Market-based performance was the only type that was not significantly impacted by institutional distance (although the sign of the effect was also negative). Interestingly, the negative effect of institutional distance on performance is about four times stronger (i.e., more negative) on subsidiary performance (β = − 0.040; p = 0.000) than on the performance of the MNC as a whole (β = − 0.009; p = 0.031). This finding is consistent with a recent study on cultural distance (Beugelsdijk et al., 2018b).

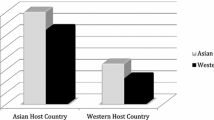

Furthermore, we observe some interesting differences depending on the theoretical tradition and institutional dimensions used. Specifically, while the effect of formal distance (institutional economics) is insignificant (β = − 0.001; p = 0.925), the effect of regulatory distance (organizational institutionalism) is negative and significant (β = − 0.038; p = 0.000). We also find a significant negative effect when institutional distance is measured unidimensionally (β = − 0.022; p = 0.001) (often using the same indicators as for formal and regulatory distance). For a more refined analysis, we further replicated the test on a smaller sub-sample of papers that used both multiple home and multiple host countries. The reason is that there has been a concern in the literature (Brouthers, Marshall, & Keig, 2016; van Hoorn & Maseland, 2016) that studies which use one home and multiple host countries might in fact be capturing “profile” rather than “distance” effects. In those cases, results are driven by the institutional characteristics of the host country regardless of how “distant” it is from the home country. This is especially relevant when the focus is on regulatory and formal institutions. Interestingly, as seen in Table 4, in this smaller and stricter subsample, we found no significant performance effect for formal, regulatory, and unidimensional measures of institutional distance. There is a negative and significant effect of informal distance (most often measured by Hofstede’s cultural dimensions) on performance, again consistent with previous meta-analyses on cultural distance and performance (Beugelsdijk et al., 2018b; Magnusson, Baack, Zdravkovic, Satub, & Amine, 2008). We believe that these results are among the most interesting analytical findings in our review, showing that methodological approaches, including sample structure (number of home and host countries), and the particular measurement approach employed, matter greatly for the results, even to the extent that they may render institutional distance insignificant.

The meta-analytical technique allowed us to also test for possible contingency effects of the way institutional distance is measured in terms of both method and data source. Table 4 shows that the vast majority of the papers use either the Kogut and Singh index or another Euclidean distance index, and that both approaches find a negative and significant relationship with performance. Studies using the Mahalanobis distance (Berry et al., 2010) show the strongest negative relationship with performance (β = − 0.118; p = 0.000). Studies that simply take the difference between the home and a host country score on an indicator (β = − 0.009; p = 0.059), or in which it is unclear what method is used to measure distance, also have a negative and significant relationahip (β = − 0.009; p = 0.030). It therefore appears that all these measurement methods are effective in capturing the relationship between institutional distance and performance. The Mahalanobis method is perhaps preferable given its unique ability to also account for the correlation between the different institutional dimensions (Berry et al., 2010).

The analysis of the impact of the data source used is less straightforward due to the variety in measures and data sources, as well as the interchangeable use of overlapping data for different institutional dimensions and variables. We do not have a sufficient number of studies to provide a comprehensive analysis of all possible methodological effects slicing the sample by database, distance dimension, and sample structure used. What we can say, however, is that, specifically for those distance dimensions that are most at risk of conflating distance and profile effects (i.e., formal, regulatory, and unidimensional), we find notable differences in results depending on the data source used. For example, there is a negative and significant coefficient for distances using the WGI (β = − 0.018; p = 0.062), EFI (β = − 0.036; p = 0.000), and the regulatory distances using the GCR item set (β = − 0.019; p = 0.019). In contrast, both the regulatory distances using the WCY (β = 0.033; p = 0.140), and the International Country Risk (ICR) guide (β = 0.007; p = 0.618) find a positive but insignificant coefficient.

Entry Mode

Table 5 presents summary results for the relationship between institutional distance and entry mode. Entry mode refers to the degree of ownership taken by an MNC in a foreign venture. In the primary studies, entry mode is most frequently measured as a continuous variable or percentage of ownership (167 correlations; e.g., Malhotra & Gaur, 2014), followed by a dummy variable taking the value of 1 for full ownership and 0 for partial (162 correlations; e.g., Gaur & Lu, 2007), and a categorical variable of minority versus majority versus wholly-owned (35 correlations; e.g., Xu et al., 2004).

Similar to performance, we find an overall negative and significant relationship between institutional distance and entry mode. Greater institutional distance is associated with lower commitment in terms of degree of ownership, irrespective of the way entry mode is operationalized (dummy, continuous, or categorical) (β = − 0.029 and p = 0.000). Also similar to performance, we find opposing results for formal distance (insignificant with β = − 0.016 and p = 0.348), regulatory distance (significant with β = − 0.049 and p = 0.005), and a unidimensional operationalization of institutional distance (insignificant with β = 0.003 and p = 0.685). We do not have a sufficient number of studies to look into the effect of sample structure on the various distances, but, as seen in Table 5, in studies with multiple home and host countries, the effect of formal distance is not significant (β = 0.006 and p = 0.746). We present this result with caution given the small number of such studies in our sample which do not allow drawing definitive conclusions (the number of correlations is 35). In contrast, informal distance appears to be rather stable, showing a negative and significant effect on entry mode (β = − 0.069 and p = 0.000) irrespective of sample structure (β = − 0.071 and p = 0.000 for the sample with multiple home and host countries).

Establishment Mode and Location Choice

We find no significant relationship between institutional distance and establishment mode (acquisition vs. greenfield; β = 0.021; p = 0.146). The number of establishment mode studies using multiple dimensions (either formal–informal, or regulatory–normative–cognitive) is too small to draw robust conclusions (detailed results in the “Appendix”). Interestingly, the institutional distance effect becomes positive and significant in studies using multiple home and host countries (β = 0.035; p = 0.027). We interpret this as support for our more general observation that, to understand institutional distance effects, it is critical to distinguish distance effects from the direct (i.e., “profile”) institutional effects of the respective country. The latter conclusion also applies to location choice studies. Here, we find a general negative and significant relationship between institutional distance and location choice (β = − 0.028; p = 0.087), but this effect turns insignificant in studies using multiple home and host countries (β = − 0.017; p = 0.343).

The state of institutional distance research

Our review of the 171 papers combined with the meta-analysis on 137 of them provides sufficient grounds for evaluating the current state of institutional distance research. We can conclude that institutional distance has firmly established itself as one of the core constructs in international business research, and has enriched our understanding of a number of important phenomena for firms doing business across borders. Moreover, a diverse set of methods and measures have been developed and used for capturing institutional distance, and there even seems to be an emerging convergence on some best practices in methodology.

At the same time, our review uncovered certain problems, showing that this literature can sometimes be ill-defined theoretically and less than rigorous empirically. This is reminiscent of past critiques of cultural distance research (Kirkman et al., 2006; Maseland, Dow & Steel, 2018; Shenkar, 2001; Tung & Verbeke, 2010; Zaheer et al., 2012), although it is our impression that these issues are even more pervasive for institutional distance. This is perhaps so because cultural distance research has been around longer and has matured as a field of inquiry (Cuypers, Ertug, Heugens, Kogut, & Zhou, 2018). While the concept of culture is equally broad and multi-faceted as institutions, international business scholars have converged on using a narrower subset of culture theories and frameworks (e.g., Hofstede, 1980; House, Hanges, Javidan, Dorfman, & Gupta, 2004; Schwartz, 1994, 1999; Peterson & Barreto, 2018), allowing a more precise and consistent theorizing on the effects of cultural distance. There has not been such a maturation of the institutional distance research. On the contrary, there seems to be a continuing proliferation of conceptualizations and applications. This might also be partially caused by the richness of the institutional perspective as well as the abundance of country-level secondary data of institutional nature. Below, we discuss several key problematic areas and suggest ways in which this area of research can be streamlined and strengthened.

Theoretical Ambiguities

We found that the papers in our study are not sufficiently explicit and precise with regard to the particular strand of institutional theory they draw upon, whether organizational institutionalism, institutional economics, or comparative institutionalism. There are exceptions where authors clearly and consistently anchor their theoretical models and methodologies in a particular perspective (e.g., Dikova, Sahib, & Witteloostuijn, 2010; Estrin et al., 2009; Kostova, 1996; Madsen, 2009). However, many papers lack such clarity, either not specifying the perspective they take or mixing ideas from multiple perspectives, muddling the theoretical argumentation (see Tables 1, 2). This can lead to at least two problems.

First, when a paper is not clearly anchored in a particular institutional model, it is less likely to utilize its theoretical rigor and provide a precise and sharp theoretical argumentation for the proposed effects of institutional distance. This results in a rather generic discussion without deep institutional explanations and a somewhat superficial application of the construct as a “one-size-fits-all” or “catch-all” treatment of country differences. Ultimately, it reflects a simplistic view on the impact of institutional distance affecting all phenomena of cross-border nature in a similar and negative way. Our observation is that this problem is particularly common in studies conceiving of institutional distance as a unidimensional construct (see Table 1).

Second, the three institutional perspectives differ in their main theoretical theses, which are anchored, respectively, in distinct disciplines, sociology, economics, and political science, and associated with distinct levels of analysis, theoretical explanations, assumptions, and boundary conditions. When papers mix perspectives indiscriminately, they run the risk of logical inconsistency in their predictions. As discussed above, organizational institutionalism and institutional economics may, but need not, make the same predictions on the impact of distance on firms. For example, examining the challenges of entry of emerging market firms going to developed economies, organizational institutionalism is likely to suggest a negative impact of distance, while institutional economics might emphasize the positive learning opportunities for the firm entering an institutionally developed and stable market. Equally problematic is the common practice that we observed of equating culture with informal institutions and also with the cognitive or normative pillars from Scott’s framework.

A related theoretical problem concerns the rigor of the presented explanatory mechanisms of institutional distance effects. Although most of the papers reviewed provide some theoretical explanations, many reiterate similar arguments in linking different institutional variables to different organizational outcomes. For example, formal and regulatory institutions have been suggested to influence a number of different outcomes based on the same set of standard explanations, often referring to increasing costs of doing business abroad. This is also often the case for informal institutions or cognitive and normative pillars. Furthermore, some papers that treat institutional distance as multidimensional do not always develop arguments for the differential effects of the different pillars, proposing instead a generic distance effect and thus failing to utilize the opportunities that the unique pillars provide for enriching the theory.

In our view, all of these critical shortcomings in the existing literature on institutional distance can be easily corrected by a more careful and disciplined approach. The first step in distance studies should be to specify the particular theoretical perspective employed. The choice of which perspective to use should be driven by what is most theoretically appropriate given the phenomenon under study and the particular research question asked. Is the story primarily one of social embeddedness in institutionalized ways of conducting certain functions that are consistent with rules and regulation and are viewed as socially appropriate and legitimate? Or is it one of the quality of market institutions and the related risks, uncertainty, and costs? Or is our research question best tackled through the lens of a national system of institutional order whereby different aspects of the environment logically hang together? The answer to these questions will lead scholars to choose organizational institutionalism (Scott, 1995), institutional economics (North, 1990, 1991), or comparative institutionalism (Hall & Soskice, 2001; Whitley, 1999; Jackson & Deeg, 2008, 2019) as their main theoretical framework. Anchoring a study and explicitly conveying the chosen perspective provides a clear starting point and a solid foundation for building the arguments, developing the propositions and hypotheses, as well as designing the proper methodology for conducting the research.

Distance versus Profile

One of the most shocking findings in our review was the non-significant relationship between three commonly used institutional distances (unidimensional, formal, and regulatory) and firm performance, which we found in the meta-analytical tests in the smaller balanced sub-sample of studies using multiple home and host countries. This was in contrast to the significant relationship of these variables in the imbalanced samples with one home or one host country. This analysis provides statistical evidence for concerns previously raised in the literature about the potential dangers of conflating distance and direct (“profile”) effects caused by certain research design solutions (Brouthers et al., 2016; Harzing & Pudelko, 2016; van Hoorn & Maseland, 2016). The distinction between institutional profile (the set of regulatory, cognitive, and normative institutions in a given country) and institutional distance (the difference of the institutional profiles of two countries) was recognized in the initial work in this area (Kostova, 1996). However, it has been ignored in some subsequent applications, by framing studies in terms of distance but presenting arguments based on the institutional conditions of a host country (profile). We often observed this conflation of distance and profile effects in work on entry or locational decisions or performance in emerging markets, where authors describe distance effects by discussing the poor institutional conditions in the target market (e.g., Romero-Martinez et al., 2019). There is an implicit assumption in these papers that the investor comes from an institutionally developed home country, most often the US, which means that the distance measures capture the deviation of the host countries’ institutional environments from the mature market institutional environment at home. In this case, the sign of the difference between home and host tends to be always in one direction, from high to low quality of institutions. Finally, it should be noted that distance is not always the appropriate framing; some studies, because of their specific research questions, should focus instead on the direct effects of institutional profile of a particular country (host or home).

Another fascinating result in our analysis showed that this design issue (single home or host country) is not a problem for informal institutions, as evidenced by the robust effects of informal and normative institutional distance. We believe this is due to the distinct conceptual nature of formal versus informal institutions, in particular the directionality of formal distance and the neutrality of informal distance. Especially in light of the measures used for these variables (measuring informal institutions through Hofstede’s cultural value dimensions), it becomes clear that regulatory and formal institutional aspects range on a scale from unfavorable to favorable, poor to good, weak to strong, while cultural values are just different across countries. Paying attention to the distinction between institutional distance and profile effects is critical for building stronger theoretical models and choosing proper empirical design accordingly.

Measurement Ambiguities

Our review uncovered a number of areas of concern with regard to operationalization and measurement of institutional distance. There appears to be some initial convergence on measures of formal and regulatory institutional distance, especially when it is operationalized as a general country-level construct rather than in a domain-specific way (see Table 2). There is also an increasing number of authors who opt for measuring informal institutional distance with the Hofstede-based distance index. However, our overall conclusion is that this research has not yet arrived at standardized, systematic, and theoretically driven approaches with regard to the empirical use of this construct. This, coupled with insufficient justification of the use of particular measures in many papers, raises questions about the rigor of this work and may lead some to believe that certain measures are being used out of convenience, even if they are not the most appropriate theoretically and empirically. Furthermore, as discussed above, some studies use the same data to measure different types and pillars of institutions, sometimes from different institutional perspectives. This raises serious questions about the theoretical logic and the meaning of the findings in particular studies: are they really due to institutional distance or some undefined generic variable that captures country?

Another issue is the common use of country-level secondary data, which assess institutional environments in generic terms and at the country level, and thus depart from the idea of issue specificity, particularly important in the organizational institutionalism perspective. This is especially problematic when the cognitive dimension of institutional environments is considered. Using country-level measures of cultural values (e.g., Hofstede), which we found to be a common approach, is a big departure from the original meaning of this dimension as the shared knowledge and the taken-for-granted ways of conducting certain business functions (Kostova, 1996).

While the literature on institutional distance is still in its growth and maturation stage, we believe that there are ways in which these measurement ambiguities can be addressed to improve validity and rigor. For organizational institutionalism, the main remedies include: (1) carefully specify the level of analysis, as it can be field, industry, country, or meta-environment; (2) try to choose or develop measures of the regulatory, cognitive, and normative pillars that are issue-specific at that level, and (3) avoid using interchangeably the same measures for the different institutional dimensions (e.g., normative measured through regulatory indicators, or cognitive measured through Hofstede’s cultural values). Ultimately, the goal should be to employ measures that capture in the best possible way the three-pillar aspects of the institutional environment that are the closest to the phenomena under study and thus are true to the theoretical roots of this perspective. This can be done in at least two ways. First, given the wide availability of various databases nowadays capturing institutional context, researchers could identify measures that are close to the issue under study. For example, to evaluate the institutional environment with regard to CSR, one could look for secondary data that describes regulations, social knowledge, and norms related to CSR, as opposed to using some generic country-level indicators. Alternatively, if such measures are unavailable or unsatisfactory, it would be theoretically appropriate and worth the effort for scholars to develop a customized survey instrument that measures the institutional environment for the particular domain of interest. Both of these approaches are true to the theoretical logic of organizational institutionalism.

For the institutional economics perspective, scholars should use measures and operationalization of formal and informal institutions with caution. For example, we observed some recent convergence in using WGI and EFI for measuring formal institutional distance. However, it should be understood that, while both of these databases measure formal institutions in a given country, they focus on different aspects reflecting different institutional domains. WGI measure quality of governance, such as rule of law, degree of corruption, and strength of political institutions, all of which can be linked to North’s ideas of ease of doing business, market-supporting institutions, transactions costs, and uncertainty. The EFI focuses on the degree to which economic actors are free from government interference and government-imposed constraints and regulations in different areas of economic activity, such as the labor market, capital market, trade policies, investment regulations, and others. Using these sources interchangeably may be inconsistent with the theories employed. In our view, the EFI might have a slight ideological bend as it is anchored in neo-liberal philosophy and the assumption of free market superiority. Thus, the WGI might be more in line with the conceptual essence of North’s formal institutions.

Furthermore, the recent tendency to use Hofstede-based cultural distance as a measure of informal distance in the same perspective is problematic. As we have discussed, culture does not adequately capture the idea of informality as a substitute for weak formal institutions, as conceived by North (1990, 1991). Cultural values are different across countries, but they cannot be automatically assumed to have the capacity to substitute for deficient formal institutions. For example, it is hard to argue that Kogut and Singh’s (1988) cultural distance index is a substitute for poor rule of law or low investment freedom in a country. Thus, researchers need to be more careful and precise in measuring informal institutions and informal distance in this tradition. It might be useful to start rethinking the way we have operationalized informal institutions in this tradition. Could we explore concepts that better capture the informal mechanisms facilitating economic transactions and coordinated activities in a particular country like guanxi in China (e.g., Xin & Pearce, 1996), networked capitalism in the form of keiretsu in Japan (e.g., Dyer, 1996), business groups in Latin America and East Asia (e.g., Guillén, 2002; Khanna & Palepu, 2000; Kim, Kim & Hoskisson, 2010), public social capital (Adler & Kwon, 2002; Putnam, 1993), and others? While these ideas require much further work, they seem to be closer to the notion of informal institutions in North’s sense than the cultural value frameworks of Hofstede (1980) or Schwartz (1994, 1999).

Conclusion

International business scholars have significantly expanded institutional theory by exploring the distinct cross-border condition that defines their domain of inquiry (Westney, 1993; Zaheer et al. 2012). The introduction of the construct of institutional distance, which develops the notion of institutional embeddedness to the international setting, and the voluminous work examining distance effects on various business outcomes, exemplify such contributions. Our review has documented the growth and proliferation of this literature and has analyzed its current state based on the three institutional perspectives: organizational institutionalism, institutional economics, and comparative institutionalism. We have synthesized the main findings and contributions in distance research, identified key theoretical and empirical ambiguities in the literature, and suggested some concrete recommendations for strengthening this line of work.

We believe that the richness of the institutional perspective reflected in its three strands has been extremely beneficial for institutional distance research, providing numerous opportunities to study the cross-border impact on various strategic and organizational outcomes. At the same time, it has led to a number of ambiguities and problems in this area because international business scholars have often failed to recognize and/or articulate the distinct theoretical and empirical implications of the three perspectives. Thus, our overarching recommendation for strengthening distance research is to follow a more thoughtful and disciplined approach, starting with a clear determination of which institutional perspective is followed in a particular paper and why. This would lead to better explanation of the mechanisms linking institutional distance to the outcomes of interest and would drive the selection of appropriate measures “in sync” with the chosen perspective. Many of the detailed suggestions presented above can be adopted almost immediately, putting the field in the best possible position to build a reliable, replicable, and generalizable stock of knowledge on institutional distance. Others, for example, the incorporation of comparative institutionalism into distance research, are more challenging.

References

Abdi, M., & Aulakh, P. S. 2012. Do country-level institutional frameworks and interfirm governance arrangements substitute or complement in international business relationships? Journal of International Business Studies, 43(5): 477–497.

Adler, P., & Kwon, S. W. 2002. Social capital: Prospects for a new concept. Academy of Management Review, 27(1): 17–40.

Aguilera, R. V., & Grøgaard, B. 2019. The dubious role of institutions in international business: A road forward. Journal of International Business Studies, 50(1): 20–35.

Ahrens, C., Oehmichen, J., & Wolff, M. 2018. Expatriates as influencers in global work arrangements: Their impact on foreign-subsidiary employees’ ESOP participation. Journal of World Business, 53(4): 452–462.

Ang, S. H., Benischke, M. H., & Doh, J. P. 2015. The interactions of institutions on foreign market entry mode. Strategic Management Journal, 36(10): 1536–1553.

Arslan, A., Tarba, S. Y., & Larimo, J. 2015. FDI entry strategies and the impacts of economic freedom distance: Evidence from Nordic FDIs in transitional periphery of CIS and SEE. International Business Review, 24(6): 997–1008.

Bae, J. H., & Salomon, R. 2010. Institutional distance in international business research. In T. Devinney, T. Pedersen, & L. Tihanyi (Eds.) The past, present and future of international business and management: 327–349. Bingley, UK: Emerald.

Baik, B., Kang, J.-K., Kim, J.-M., & Lee, J. 2013. The liability of foreignness in international equity investments: Evidence from the US stock market. Journal of International Business Studies, 44(4): 391–411.

Berry, H., Guillén, M. F., & Zhou, N. 2010. An institutional approach to cross-national distance. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(9): 1460–1480.

Beugelsdijk, S., Ambos, B., & Nell, P. 2018a. Conceptualizing and measuring distance in international business research: Recurring questions and best practice guidelines. Journal of International Business Studies, 49(9): 1113–1137.

Beugelsdijk, S., Kostova, T., Kunst, V. E., Spadafora, E., & van Essen, M. 2018b. Cultural distance and firm internationalization: A meta-analytical review and theoretical implications. Journal of Management, 44(1): 89–130.

Beugelsdijk, S., & Mudambi, R. 2013. MNEs as border-crossing multi-location enterprises: The role of discontinuities in geographic space. Journal of International Business Studies, 44(5): 413–426.

Bhaumika, S. K., Owolabib, O., & Sarmistha, P. 2018. Private information, institutional distance, and the failure of cross-border acquisitions: Evidence from the banking sector in Central and Eastern Europe. Journal of World Business, 53(4): 504–513.

Bijmolt, T. H., & Pieters, R. G. 2001. Meta-analysis in marketing when studies contain multiple measurements. Marketing Letters, 12(2): 157–169.

Brouthers, K. D., Brouthers, L. E., & Werner, S. 2008. Resource-based advantages in an international context. Journal of Management, 34(2): 189–217.

Brouthers, L. E., Marshall, V. B., & Keig, D. L. 2016. Solving the single-country sample problem in cultural distance studies. Journal of International Business Studies, 47(4): 471–479.

Brown, L. W., Yaşar, M., & Rasheed, A. A. 2018. Predictors of foreign corporate political activities in United States politics. Global Strategy Journal, 8(3): 503–514.