Abstract

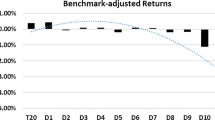

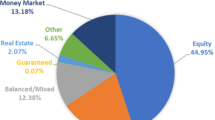

This study examines the impact of mismatch between prospectus benchmark and fund objectives on benchmark-adjusted fund performance and ranking in a sample of 1281 US equity mutual funds. All funds in our sample report S&P500 index as a prospectus benchmark, yet 2/3 of those are placed in the Morningstar category with risk and objectives different to those of the S&P500 index. We identify more appropriate ‘category benchmarks’ for those mismatched funds and obtain their benchmark-adjusted alphas using recent Angelidis et al. (J Bank Finance 37(5):1759–1776, 2013) methodology. We find that S&P500-adjusted alphas are higher than ‘category benchmark’-adjusted alphas in 61.2% of the cases. In terms of fund quartile rankings, 30% of winner funds lose that status when the prospectus benchmark is substituted with the one better matching their objectives. In the remaining performance quartiles, there is no clear advantage of using S&P 500 as a benchmark. Hence, the prospectus benchmark can mislead investors about fund’s relative performance and ranking, so any reference to performance in a fund’s prospectus should be treated with caution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

25 February 2019

After publication in Vol 20 Issue 1, it was noticed that the affiliations of authors Irina Bezhentseva Mateus and Cesario Mateus were incorrectly given as Cass Business School, City, University of London, London, UK.

Notes

Investment Company Institute, Understanding Investor Preferences for Mutual Fund Information, Summary of Research Findings (“Understanding Investor Preferences”), 2006, available at https://www.ici.org/pdf/rpt_06_inv_prefs_full.pdf.

The paper with MATLAB code is available from:https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2581737.

The results presented are obtained with the use of the Carhart model in AGT augmentation. The outcomes obtained with Fama–French three- and five-factor models are qualitatively the same and available upon request.

In the UK for instance, the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) recently recognised the need for better transparency related to fund objectives and benchmark choice in their ‘Asset Management Market Study’ (published June 2017, accessed May 2018): https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/market-studies/ms15-2-3.pdf.

https://web.stanford.edu/~wfsharpe/art/fa/fa.htm Accessed 28 September 2018.

There is no relevant change in categories of our funds over the sample period.

The full set of R-squared values corresponding to Fig. 1 and Wilcoxon z-tests of their difference are available on request.

who report nonzero alphas for passive benchmark indices.

US market risk premium is defined as the value-weighted return of all CRSP firms incorporated in the US and listed on the NYSE, AMEX or NASDAQ (Rm) minus 1-month US Treasury bill (Rf).

Similar could be obtained using Chinthalapati et al. (2017) methodology for benchmark-adjusted alphas.

Kenneth French’s website: http://mba.tuck.dartmouth.edu/pages/faculty/ken.french/data_library.html.

Serial correlation of residuals does not cause biases in our results. For 85% of the funds in our sample, we accept the Breuch–Godfrey null hypothesis of no serial correlation with a lag of 1 (83% of funds when a lag of 12 is used to test for seasonality).

Full set of these results are available on request.

The full set of tables for AGT with three and five factors, fully comparable to Table 4 based on four-factor model, are available on request.

References

Angelidis, T., D. Giamouridis, and N. Tessaromatis. 2013. Revisiting mutual fund performance evaluation. Journal of Banking & Finance 37 (5): 1759–1776.

Bams, D., R. Otten, and E. Ramezanifar. 2016. Investment style misclassification and mutual fund performance, working paper.

Blitz, D., M.X. Hanauer, M. Vidojevic, and P. van Vliet. 2018. Five concerns with the five-factor model. The Journal of Portfolio Management Quantitative Special Issue 44 (4): 71–78.

Carhart, M.M. 1997. On persistence in mutual fund performance. The Journal of finance 52 (1): 57–82.

Chan, L.K., S.G. Dimmock, and J. Lakonishok. 2009. Benchmarking money manager performance: issues and evidence. Review of Financial Studies 22 (11): 4553–4599.

Chen, H., and G. Bassett. 2014. What does β SMB > 0 really mean? The Journal of Financial Research 37 (4): 543–552.

Chinthalapati, V.L., C. Mateus, and N. Todorovic. 2017. Alphas in disguise: a new approach to uncovering them. International Journal of Finance and Economics 22 (3): 234–243.

Costa, B., and K. Jakob. 2006. Do stock indexes have abnormal performance? The Journal of Performance Measurement 11 (1): 8–18.

Cremers, K.M., and A. Petajisto. 2009. How active is your fund manager? A new measure that predicts performance. Review of Financial Studies 22 (9): 3329–3365.

Cremers, M., A. Petajisto, and E. Zitzewitz. 2012. Should benchmark indices have alpha? Revisiting performance evaluation. Critical Finance Review 2: 1–48.

Daniel, K., M. Grinblatt, S. Titman, and R. Wermers. 1997. Measuring mutual fund performance with characteristics-based benchmarks. Journal of Finance 52: 1035–1058.

DiBartolomeo, Dan, and E. Witkowski. 1997. Mutual fund misclassification: evidence based on style analysis. Financial Analysts Journal 53: 32–43.

Elton, E., M. Gruber, and C. Blake. 2003. Incentive fees and mutual funds. Journal of Finance 58: 779–804.

Fama, E.F., and K.R. French. 1993. Common risk factors in the returns on stocks and bonds. Journal of Financial Economics 33: 3–56.

Fama, E., and K. French. 2015. A five-factor asset pricing model. Journal of Financial Economics 116: 1–22.

Fama, E. and K. French. 2016. Dissecting anomalies with five factor model. Review of Financial Studies 29: 70–103.

Fung, W., and D.A. Hsieh. 2002. Hedge-fund benchmarks: information content and biases. Financial Analysts Journal 58: 22–34.

Goetzmann, W., J. Ingersoll, M. Spiegel, and I. Welch. 2007. Portfolio performance manipulation and manipulation-proof performance measures. Review of Financial Studies 20 (5): 1503–1546.

Howard, C.T. 2010. The importance of investment strategy, Working paper. Available on SSRN: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1562813. Accessed 1 Nov 2018.

Huang, J., C. Sialm, and H. Zhang. 2011. Risk shifting and mutual fund performance. Review of Financial Studies 24 (8): 2575–2616.

Jiang, H., M. Verbeek, and Y. Wang. 2014. Information content when mutual funds deviate from benchmarks. Management Science 60 (8): 2038–2053.

Kacperczyk, M., C. Sialm, and L. Zheng. 2008. Unobserved actions of mutual funds. The Review of Financial Studies 21 (6): 2379–2416.

Kim, M., R. Shukla, and M. Tomas. 2000. Mutual fund objective misclassification. Journal of Economics and Business 52 (4): 309–323.

Mateus, I.B., C. Mateus, and N. Todorovic. 2016. UK equity mutual fund alphas make a comeback. International Review of Financial Analysis 44: 98–110.

Sensoy, B.A. 2009. Performance evaluation and self-designated benchmark indexes in the mutual fund industry. Journal of Financial Economics 92 (1): 25–39.

Sharpe, W.F. 1992. Asset allocation: management style and performance measurement. Journal of portfolio Management 18 (2): 7–19.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mateus, I.B., Mateus, C. & Todorovic, N. Benchmark-adjusted performance of US equity mutual funds and the issue of prospectus benchmarks. J Asset Manag 20, 15–30 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41260-018-0101-z

Revised:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41260-018-0101-z

Keywords

- Prospectus benchmark selection

- Mutual fund benchmark mismatch

- Benchmark-adjusted alphas

- Performance ranking