Abstract

This paper investigates the determinants of citizens’ assessment of the degree of democracy in France, based on the ESS Round 6 data. A substantial share of respondents claims that France is barely democratic or not democratic at all, while still another nonnegligible share gives France the highest possible score on a 11-point democracy scale. We find that democracy assessment is mostly driven by political variables and by policy evaluations rather than by respondents’ own social and economic status. Individuals who endorse a minimal definition of democracy are overall less critical of their political system. We also find that respondents who identify with the current government party are consistently more likely to rate France higher on the democracy scale, while voters who identify with a non-governing party do not rate France differently from those who do not feel close to any party. Respondents who consider that the government adequately fights income inequalities are much more likely to consider France democratic. Finally, results regarding the impact of respondents’ socio-economic status are inconclusive.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See Marshall et al. (2016). Data are available at http://www.systemicpeace.org/inscrdata.html. To facilitate comparisons, we rely on the 11-points democracy scale “DEMOC” instead of Polity’s composite democracy-autocracy scale.

The ESS survey on which this study is based upon has been administered between January and June 2013.

These figures come from the Eurobarometer 80 administered in November 2013.

These figures are drawn from the TNS-Kanter barometer on the popularity of the French president: http://www.tns-sofres.com/dataviz?type=1&code_nom=hollande&start=1&end=12&submit=Ok.

These figures come from the Electoral System website of Michael Gallagher (TCD), with the complete list of indices available online: http://www.tcd.ie/Political_Science/staff/michael_gallagher/ElSystems/Docts/ElectionIndices.pdf.

The 3.44 and a skewness of −0.75: both values are significantly different from the values we would have found under normal distribution (p < 0.001). We additionally ran a Shapiro–Wilk test, which confirms that the variable is not normally distributed (p < 0.001).

The ESS also asks respondents whether they think each of these democratic criteria are actually fulfilled in their own country. Yet, we decided not to use these items and to rely solely on the importance respondents assign to these aspects of democracy, in order to minimize endogeneity issues. Even if respondents who describe their own system as nondemocratic are also more likely to evaluate the state of direct and social democracy in their country as very bad, we cannot ascertain if the former really is a consequence of the latter or if respondents respond similarly to all items for reasons of consistency or because they are generally dissatisfied with the whole system.

In order to know which parties have been in power in France in the last 20 years (since 1992), we have used the Parlgov database, taking into account the fact that several of the parties mentioned in the list did not exist in 1992 and are the result of mergers, splits or changes of party labels: Döring, Holger and Philip Manow. 2016. Parliaments and governments database (ParlGov): Information on parties, elections and cabinets in modern democracies. Development version. The parties in government in 2012 (coded 3) are the following: Parti Socialiste (PS), Europe Ecologie les Verts (EELV), Parti Radical de Gauche (PRG). Parties that have been in the government within the last 20 years (coded 2) include Nouveau Centre (NC), Parti Radical Valoisien, Union des démocrates et indépendants (UDI), Union pour un movement populaire (UMP), Mouvement démocrate (MODEM), Parti communiste français (PCF). Parties that have never been in government (coded 1) include Nouveau Parti Anticapitaliste (NPA), Lutte ouvrière (LO), Parti de gauche (PG), Mouvement pour la France (MPF), autres.

We also ran a likelihood-ratio test in order to see which of the two procedures fits the data better. The test confirms that the multinomial logit is more adequate (p < 0.0001).

Switching the reference category from 0 to 2 indicates that there is also no statistically significant difference in evaluations between respondents who identify with a permanently losing party and those who identify with a former government party.

We do find a slight negative effect of direct democracy in the ordered logit model, but the coefficient switches sign when Electoral democracy is removed from the model.

References

Abedi, Arim. 2002. Challenges to Established Parties: The Effects of Party System Features on the Electoral Fortunes of Anti-Political-Establishment Parties. European Journal of Political Research 41(4): 551–583.

Acemoglu, Daron, and James A. Robinson. 2006. Economic Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Anderson, Christopher J. 2011. Electoral Supply, Median Voters, and Feelings of Representation in Democracies. In Citizens, Context, and Choice: How Context Shapes Citizens’ Electoral Choices, ed. Russell J. Dalton and Christopher J. Anderson, 214–240. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Anderson, Christopher J., and Matthew M. Singer. 2008. The Sensitive Left and the Impervious Right. Comparative Political Studies 41(4–5): 564–599.

Anderson, Christopher J., André Blais, and Shaun Bowler. 2005. Losers’ Consent: Elections and Democratic Legitimacy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Anderson, Christopher J., and Christine A. Guillory. 1997. Political Institutions and Satisfaction with Democracy: A Cross-National Analysis of Consensus and Majoritarian Systems. American Political Science Review 91(1): 66–81.

Ariely, Gal, and Eldad Davidov. 2011. Can We Rate Public Support for Democracy in a Comparable Way? Cross-National Equivalence of Democratic Attitudes in the World Value Survey. Social Indicators Research 104(2): 271–286.

Armingeon, Klaus, and Kai Guthmann. 2014. Democracy in Crisis? The Declining Support for National Democracy in European Countries, 2007–2011. European Journal of Political Research 53(3): 423–442.

Armingeon, Klaus, Kai Guthmann, and David Weisstanner. 2016. How the Euro Divides the Union: The Effect of Economic Adjustment on Support for Democracy in Europe. Socio-Economic Review 14(1): 1–26.

Beaudonnet, Laurie, André Blais, Damien Bol, and Martial Foucault. 2014. The Impact of Election Outcomes on Satisfaction with Democracy under a Two-Round System. French Politics 12(1): 22–35.

Bengtsson, Åsa, and Mikko Mattila. 2009. Direct Democracy and Its Critics: Support for Direct Democracy and ‘Stealth’ Democracy in Finland. West European Politics 32(5): 1031–1048.

Bernauer, Julian, and Adrian Vatter. 2012. Can’t Get No Satisfaction with the Westminster Model? Winners, Losers and the Effects of Consensual and Direct Democratic Institutions on Satisfaction with Democracy. European Journal of Political Research 51(4): 435–468.

Blais, André, and François Gélineau. 2007. Winning, Losing and Satisfaction with Democracy. Political Studies 55(2): 425–441.

Blais, André, Alexandre Morin-Chassé, and Shane P. Singh. 2017. Election Outcomes, Legislative Representation, and Satisfaction with Democracy. Party Politics 23(2): 85-95.

Bowler, Shaun, Todd Donovan, and Jeffrey A. Karp. 2002. When Might Institutions Change? Elite Support for Direct Democracy in Three Nations. Political Research Quarterly 55(4): 731–754.

Bowler, Shaun, Todd Donovan, and Jeffrey A. Karp. 2007. Enraged or Engaged? Preferences for Direct Citizen Participation in Affluent Democracies. Political Research Quarterly 60(3): 351–362.

Bratton, Michael, and Robert Mattes. 2001. Support for Democracy in Africa: Intrinsic or Instrumental? British Journal of Political Science 31(03): 447–474.

Bratton, Michael, Robert B. Mattes, and E. Gyimah-Boadi. 2005. Public Opinion, Democracy, and Market Reform in Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Braun, Daniela, and Markus Tausendpfund. 2014. The Impact of the Euro Crisis on Citizens’ Support for the European Union. Journal of European Integration 36(3): 231–245.

Canache, Damarys, Jeffery J. Mondak, and Mitchell A. Seligson. 2001. Meaning and Measurement in Cross-National Research on Satisfaction with Democracy. Public Opinion Quarterly 65(4): 506–528.

Ceka, Besir, and Pedro C. Magalhaes. 2016. How People Understand Democracy: A Social Dominance Approach. In How Europeans View and Evaluate Democracy, ed. Monica Ferrín and Hanspeter Kriesi, 90–110. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chu, Yun-han, Michael Bratton, Marta Lagos, and Mark A. Tessler. 2008. Public Opinion and Democratic Legitimacy. Journal of Democracy 19(2): 74–87.

Cordero, Guillermo, and Pablo Simón. 2016. Economic Crisis and Support for Democracy in Europe. West European Politics 39(2): 305–325.

Córdova, Abby, and Mitchell A. Seligson. 2009. Economic Crisis and Democracy in Latin America. PS. Political Science & Politics 42(4): 673–678.

Curini, Luigi, Willy Jou, and Vincenzo Memoli. 2012. Satisfaction with Democracy and the Winner/Loser Debate: The Role of Policy Preferences and Past Experience. British Journal of Political Science 42(2): 241–261.

Dahl, Robert A. 2000. A Democratic Paradox? Political Science Quarterly 115(1): 35–40.

Dalton, Russell J. 2004. Democratic Challenges, Democratic Choices: The Erosion of Political Support in Advanced Industrial Democracies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dalton, Russell J. 2008. The Quantity and the Quality of Party Systems. Comparative Political Studies 41(7): 899–920.

Davis, Nicholas T. 2014. Responsiveness and the Rules of the Game: How Disproportionality Structures the Effects of Winning and Losing on External Efficacy. Electoral Studies 36(December): 129–136.

de Regt, Sabrina. 2013. Arabs Want Democracy, But What Kind? Advances in Applied Sociology 3(1): 37-46.

Delgado, Irene. 2016. How Governing Experience Conditions Winner-Loser Effects. An Empirical Analysis of the Satisfaction with Democracy in Spain after 2011 Elections. Electoral Studies 44: 76–84.

Dolez, Bernard, Annie Laurent, and Laurence Morel. 2003. Les référendums en France sous la Ve république. Revue internationale de politique comparée 10(1): 111–127.

Dompnier, Nathalie, and Raul Magni Berton. 2012. How Durably Do People Accept Democracy? Politicization, Political Attitudes and Losers’ Consent in France. French Politics 10(4): 323–344.

Donovan, Todd, and Jeffrey Karp. 2017. Electoral Rules, Corruption, Inequality and Evaluations of Democracy. European Journal of Political Research 56: 469–486.

Easton, David. 1957. An Approach to the Analysis of Political Systems. World Politics 9(3): 383–400.

Evans, Geoffrey, and Stephen Whitefield. 1995. The Politics and Economics of Democratic Commitment: Support for Democracy in Transition Societies. British Journal of Political Science 25(04): 485–514.

Ferland, Benjamin. 2015. A Rational or a Virtuous Citizenry? The Asymmetric Impact of Biases in Votes-Seats Translation on Citizens’ Satisfaction with Democracy. Electoral Studies 40: 394–408.

Ferrin, Monica, and Hanspeter Kriesi. 2016. How Europeans View and Evaluate Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gallagher, Michael. 1991. Proportionality, Disproportionality and Electoral Systems. Electoral Studies 10(1): 33–51.

Galland, Olivier, Yannick Lemel, and Alexandra Frénod. 2013. La perception des inégalités en France. Revue européenne des sciences sociales. European Journal of Social Sciences 51(1): 179–211.

Gaxie, Daniel. 1990. Au delà des apparences… [Sur quelques problèmes de mesure des opinions]. Actes de La Recherche En Sciences Sociales 81(1): 97–112.

Graham, Carol, and Sandip Sukhtankar. 2004. Does Economic Crisis Reduce Support for Markets and Democracy in Latin America? Some Evidence from Surveys of Public Opinion and Well Being. Journal of Latin American Studies 36(2): 349–377.

Grosfeld, Irena, and Claudia Senik. 2010. The Emerging Aversion to Inequality. Economics of Transition 18(1): 1–26.

Grossman, Emiliano, and Nicolas Sauger. 2014. ‘Un Président Normal’? Presidential (in-)Action and Unpopularity in the Wake of the Great Recession. French Politics 12(2): 86–103.

Grossman, Emiliano, and Nicolas Sauger. 2017. Pourquoi détestons-nous autant nos politiques ?. Paris: Presses de Sciences Po.

Hernández, Enrique. 2016. Europeans’ Views of Democracy: The Core Elements of Democracy. In How Europeans View and Evaluate Democracy, ed. Monica Ferrín and Hanspeter Kriesi, 43–63. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Howell, Patrick, and Florian Justwan. 2013. Nail-Biters and No-Contests: The Effect of Electoral Margins on Satisfaction with Democracy in Winners and Losers. Electoral Studies 32(2): 334–343.

Huppert, Felicia A., Nic Marks, Andrew Clark, Johannes Siegrist, Alois Stutzer, Joar Vittersø, and Morten Wahrendorf. 2008. Measuring Well-Being Across Europe: Description of the ESS Well-Being Module and Preliminary Findings. Social Indicators Research 91(3): 301–315.

Inglehart, Ronald, and Christian Welzel. 2005. Modernization, Cultural Change, and Democracy: The Human Development Sequence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jamal, Amaney A., and Mark A. Tessler. 2008. Attitudes in the Arab World. Journal of Democracy 19(1): 97–110.

Kiewiet de Jonge, Chad P. 2016. Should Researchers Abandon Questions about ‘Democracy’? Evidence from Latin America. Public Opinion Quarterly 80(3): 694–716.

Jou, Willy. 2009. Political Suport from Election Losers in Asian Democracies. Taiwan Journal of Democracy 5(2): 145–175.

Klingemann, Hans-Dieter. 1999. Mapping Political Support in the 1990s: A Global Analysis. In Critical Citizens: Global Support for Democratic Governance, ed. Pippa Norris, 31–56. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kotzian, Peter. 2011. Public Support for Liberal Democracy. International Political Science Review 32(1): 23–41.

Kuhn, Raymond. 2014. Mister Unpopular: François Hollande and the Exercise of Presidential Leadership, 2012–14. Modern & Contemporary France 22(4): 435–457.

Laakso, Markus, and Rein Taagepera. 1979. ‘Effective’ Number of Parties : A Measure with Application to West Europe. Comparative Political Studies 12(1): 3–25.

Lachat, Romain. 2008. The Impact of Party Polarization on Ideological Voting. Electoral Studies 27(4): 687–698.

Lewis-Beck, Michael S., and Richard Nadeau. 2015. Explaining French Elections: The Presidential Pivot. French Politics 13(1): 25–62.

Lijphart, Arend. 1984. Democracies: Patterns of Majoritarian and Consensus Government in Twenty-One Countries. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Lijphart, Arend. 1999. Patterns of Democracy. Government Forms and Performance in Thirty-Six Countries. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Luskin, Robert C. 1990. Explaining Political Sophistication. Political Behavior 12(4): 331–361.

Marshall, Monty G., Ted R. Gurr, and Keith Jaggers. 2016. Polity IV Project: Political Regimes Characteristics and Transitions, 1800-2015. Dataset Users' Manual. Center for Systemic Peace. http://www.systemicpeace.org/inscr/p4manualv2015.pdf.

Norris, Pippa. 2011. Democratic Deficit: Critical Citizens Revisited. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Paoletti, Marion. 2010. L’idéal démocratique face à ses tensions oligarchiques : de la démocratie locale à la parité. Bordeaux: Université Montesquieu Bordeaux iv, Habilitation à diriger des recherches en science politique.

Przeworski, A., S. Stokes, Bernard Manin, and James A. Stimson. 1999. “Party Government and Responsiveness.” In Democracy, Accountability, and Representation, 197–221. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rich, Timothy S. 2015. Losers’ Consent or Non-Voter Consent? Satisfaction with Democracy in East Asia. Asian Journal of Political Science 23(3): 243–259.

Rothstein, Bo, and Uslaner, Eric. 2005. All for All: Equality, Corruption, and Social Trust. World Politics 58(1): 41–72.

Sauger, Nicolas, and Sarah-Louise Raillard. 2014. The economy and the vote in 2012. An election of crisis? Revue française de science politique 63(6): 1031–1049.

Scharpf, Fritz. 1999. Governing Europe. Effective and Democratic?. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schedler, Andreas, and Rodolfo Sarsfield. 2007. Democrats with Adjectives: Linking Direct and Indirect Measures of Democratic Support. European Journal of Political Research 46(5): 637–659.

Sineau, Mariette, and Bruno Cautrès. 2013. Les attentes vis-à-vis du nouveau président. In La Décision Électoale En 2012, ed. Pascal Perrineau, 229–242. Paris: Armand Colin.

Singh, Shane, Ignacio Lago, and André Blais. 2011. Winning and Competitiveness as Determinants of Political Support. Social Science Quarterly 92(3): 695–709.

Singh, Shane P. 2014. Not All Election Winners Are Equal: Satisfaction with Democracy and the Nature of the Vote. European Journal of Political Research 53(2): 308–327.

Singh, Shane P., and Judd R. Thornton. 2016. Strange Bedfellows: Coalition Makeup and Perceptions of Democratic Performance among Electoral Winners. Electoral Studies 42: 114–125.

Teixeira, Conceição Pequito, Emmanouil Tsatsanis, and Ana Maria Belchior. 2016. A ‘Necessary Evil’ Even during Hard Times? Public Support for Political Parties in Portugal before and after the Bailout (2008 and 2012). Party Politics 22(6): 719–731.

Tiberj, Vincent. 2017. Les citoyens qui viennent. Comment le renouvellement générationnel transforme la politique en France. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

Tiberj, Vincent, Bernard Denni, and Nonna Mayer. 2013. Un choix, des logiques multiples. Revue française de science politique 63(2): 249–278.

Torcal, Mariano. 2014. The Decline of Political Trust in Spain and Portugal. American Behavioral Scientist 58(12): 1542–1567.

Van Erkel, Patrick F.A., and Tom W.G. Van Der Meer. 2016. Macroeconomic Performance, Political Trust and the Great Recession: A Multilevel Analysis of the Effects of within-Country Fluctuations in Macroeconomic Performance on Political Trust in 15 EU Countries, 1999–2011. European Journal of Political Research 55(1): 177–197.

Webb, Paul. 2013. Who Is Willing to Participate? Dissatisfied Democrats, Stealth Democrats and Populists in the United Kingdom. European Journal of Political Research 52(6): 747–772.

Acknowledgements

We want to warmly thank Isabelle Guinaudeau and Céline Bélot for their very useful comments on an earlier version of this manuscript during the seminar “Entre politique et marché : penser la contrainte économique” organized in Bordeaux in January 2017.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

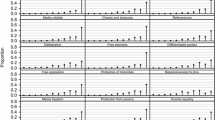

Appendices

Appendix 1: Descriptive statistics

See Tables 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 and 11.

Appendix 2: Additional estimates

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bedock, C., Panel, S. Conceptions of democracy, political representation and socio-economic well-being: explaining how French citizens assess the degree of democracy of their regime. Fr Polit 15, 389–417 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41253-017-0043-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41253-017-0043-8