Abstract

Sandroni and Squintani (Am Econ Rev 97(5):1994–2004, 2007) argue that in the presence of overconfident agents, the findings of Rothschild and Stiglitz (Q J Econ 90:629–649, 1976) no longer hold since compulsory insurance makes the low-risk agents worse off. The main assumption of Sandroni and Squintani (2007) is that there exists a causal link between overconfidence and insurance-purchasing behavior. In this paper, I use a design similar to Camerer and Lovallo (Am Econ Rev 89(1):306–318, 1999) to establish this causal link. I show that overconfident subjects purchase significantly less actuarially fair insurance when the probability of loss is unknown and it depends on their own unknown ability than when the probability of loss is known.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Bajtelsmit, V., J.C. Coats, and P. Thistle. 2015. The effect of ambiguity on risk management choices an experimental study. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 50 (3): 249–280.

Barber, B., and T. Odean. 1999. Do investors trade too much? American Economic Review 89 (5): 1279–1298.

Barber, B.M., and T. Odean. 2000. Trading is hazardous to your wealth: The common stock investment performance of individual investors. The Journal of Finance 55 (2): 773–806.

Barone-Adesi, G., Mancini, L., & Shefrin, H. (2013, July). A tale of two investors: Estimating optimism and overconfidence. In 26th Australasian Finance and Banking Conference.

Biais, B., D. Hilton, K. Mazurier, and S. Pouget. 2005. Judgmental overconfidence, self-monitoring, and trading performance in an experimental financial market. The Review of Economic Studies 72 (2): 287–312.

Bregu, K. 2020. Overconfidence and (over)trading: The effect of feedback on trading behavior. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics 88: 101598.

Camerer, C., and D. Lovallo. 1999. Overconfidence and excess entry: An experimental approach. The American Economic Review 89 (1): 306–318.

Daniel, K.D., D. Hirshleifer, and A. Subrahmanyam. 2001. Overconfidence, arbitrage, and equilibrium asset pricing. The Journal of Finance 56 (3): 921–965.

De Bondt, W.F., and R.H. Thaler. 1995. Financial decision-making in markets and firms: A behavioral perspective. Handbooks in Operations Research and Management Science 9: 385–410.

Deaves, R., Luders, E., & Luo, G. Y. (2008). An Experimental Test of the Impact of Overconfidence and Gender on Trading Activity. Review of Finance, rfn023.

Fischbacher, U. 2007. z-Tree: Zurich toolbox for ready-made economic experiments. Experimental Economics 10 (2): 171–178.

Glaser, M., and M. Weber. 2007. Overconfidence and trading volume. The Geneva Risk and Insurance Review 32 (1): 1–36.

Harrison, G.W. 2019. The behavioral welfare economics of insurance. The Geneva Risk and Insurance Review 44 (2): 137–175.

Huang, R.J., Y.J. Liu, and L.Y. Tzeng. 2010. Hidden overconfidence and advantageous selection. The Geneva Risk and Insurance Review 35 (2): 93–107.

Huang, W., & Luo, M. (2015). Overconfidence and Health Insurance Participation among the Elderly (No. 9481). Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA).

Malmendier, U., and G. Tate. 2005. CEO overconfidence and corporate investment. The Journal of Finance 60 (6): 2661–2700.

Moore, D.A., and P.J. Healy. 2008. The trouble with overconfidence. Psychological Review 115 (2): 502.

Odean, T. 1998. Volume, volatility, price, and profit when all traders are above average. The Journal of Finance 53 (6): 1887–1934.

Rothschild, M., and J. Stiglitz. 1976. Equilibrium in competitive insurance markets: An essay on the economics of imperfect information. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 90: 629–649.

Sandroni, A., and F. Squintani. 2007. Overconfidence, insurance, and paternalism. The American Economic Review 97 (5): 1994–2004.

Schade, C., H. Kunreuther, and P. Koellinger. 2012. Protecting against low-probability disasters: The role of worry. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making 25 (5): 534–543.

Scheier, M.F., C.S. Carver, and M.W. Bridges. 1994. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 67 (6): 1063.

Svenson, O. 1981. Are we all less risky and more skillful than our fellow drivers? Acta Psychologica 47 (2): 143–148.

Toplak, M.E., R.F. West, and K.E. Stanovich. 2014. Assessing miserly information processing: An expansion of the Cognitive Reflection Test. Thinking & Reasoning 20 (2): 147–168.

Viscusi, W.K. 1995. Government action, biases in risk perception, and insurance decisions. The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance Theory 20 (1): 93–110.

Funding

Funds were provided by the Economics Department at University of Arkansas.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix

See Tables 5, 6, 7, and 8 with all subjects.

Sample Instructions

Welcome, and thank you for participating in this experiment.

Just for participating, you are guaranteed a $5 payment. You can earn additional money based on your decisions, so it is important that you read the directions carefully. If you have any questions during the experiment, please raise your hand and wait for the experimenter to come to you. Please do not talk or communicate with other participants for the duration of the experiment.

This study is composed of five parts. Below you can find the information for each of these parts.

Part I

In the first part, each period you are shown 100 rectangles of various colors (red, yellow, purple, black, green, and blue), and your task is to count the number of red rectangles shown. You have 7 s to finish this task, once time runs out, you are asked to enter your best guess about the number of red rectangles. Then you will be asked a follow-up question.

Questions and Options

Options | Payoff |

|---|---|

Exact Within 1 | $33 $30 |

Within 2 Within 3 | $27 $24 |

Within 4 Within 5 | $21 $18 |

Within 6 Within 7 | $15 $12 |

Within 8 Within 9 | $9 $6 |

Guaranteed | $3 |

The question asks you to state how close your guess was to the true number of red rectangles. Your payoff in that period will depend on the accuracy of your answer. You have several options and the wider the interval you select, the less you are paid if you are correct.

If you state that your guess was the exact number of red rectangles and you are right, you will get paid $33, but if you are wrong you will earn $0.

If you state that your guess was within ± 1 and you are right, you are paid $30, but if you are wrong you will be paid $0.

If you state that your guess was within ± 2 and you are right, you are paid $27, but if you are wrong you will be paid $0.

Each consecutive row has a wider interval and a lower payment. The next to last option is:

If you state that your guess was within ± 9 and you are right, you are paid $6, but if you are wrong you will be paid $0.

The last option is a guaranteed payment of $3 which you get regardless of how accurate your guess is.

After you answer this question, you will start with another counting task with a new display of 100 rectangles and go through the same steps for a total of 10 periods.

Payment for Part I

A period will be randomly chosen from Part I of the experiment for your payoff.

Part II

Part two of the experiment is composed of 10 trivia questions. For each trivia question you answer correctly, you will receive $1, if you answer the question incorrectly you will receive $0. Hence, if you answer all 10 questions correctly, you will receive $10.

After you have answered all 10 questions, you will be asked to state the probability for each of the 11 possible scores (0 correct–10 correct) you may have received. You can enter any numbers you want, but the total must equal 100%. For instance, you can enter the probabilities as shown in the table below. Your payoff for this task will be calculated using the following formula: Payoff = 1 + r—w, where r is equal to 2 times the probability of the correct answer. In the table below, if the correct answer was 5, then r = 2 × 0.25% = $0.5, whereas w is the sum of all squared probabilities you enter w = \({\sum }_{i=0}^{i=10}{p}_{i}^{2}\), which in this case would be w = (0.0^2 + 0.0^2 + 0.10^2 + 0.20^2 + 0.20^2 + 0.25^2 + 0.05^2 + 0.15^2 + 0.05^2 + 0.0^2 + 0.0^2) = $1.07$. So if these were your choices, your payoff would equal: Payoff = 1 + 0.5 – 1.07 = $0.47.

This formula may appear complicated, but what it means for you is very simple: You get paid the most when you honestly report your best guesses about the likelihood of each of the different possible outcomes. The range of your payoffs is from $0 to $2 for your guess.

Correct questions

Number of correct questions | Probability |

|---|---|

0 | 0% |

1 | 0% |

2 | 10% |

3 | 20% |

4 | 20% |

5 | 25% |

6 | 5% |

7 | 15% |

8 | 5% |

9 | 0% |

10 | 0% |

Payment for Part II

You will get paid $1 for each correct question plus the payment for predicting your score.

Part III

In this part, you are allocated $25 and you will choose to play one of the five lotteries shown below. Once you choose a lottery, a die will be rolled and if the die rolls 1, 2, or 3 you will be paid event A if the die rolls a 4, 5, or 6 you will be paid event B.

Lottery | Event | Probability of the event | Payoff |

|---|---|---|---|

1 | Head Tail | 50% 50% | -$16.00 -$16.00 |

2 | Head Tail | 50% 50% | -$18.10 -$13.50 |

3 | Head Tail | 50% 50% | -$19.00 -$12.20 |

4 | Head Tail | 50% 50% | -$20.00 -$10.75 |

5 | Head Tail | 50% 50% | -$22.00 -$8.10 |

6 | Head Tail | 50% 50% | -$23.00 -$7.25 |

Payment for Part III

You will get paid based on the lottery you choose.

Part IV

In this part, you will be entered in a lottery and you may lose all your earnings, excluding your $5 show-up fee. You will have the option to buy insurance to cover the possible loss. You will make three decisions for this part and one of these decisions will be randomly chosen for your final payment. The probability that you lose your earnings may be different for each of these decisions. You will have the option to buy insurance to cover any amount of your earnings that you want. The insurance will be sold in units. One unit of insurance will cover $1 of your earnings and it will cost a given amount that will be less than or equal to $1. The cost of insurance will be the same for all three decisions. For example, if your total earnings are $30 and the insurance costs is $0.50 per unit. If you decide to not buy any insurance with some probability p you will earn $0 and with probability 1- p you will earn $30. If you choose to buy 15 units of insurance to cover $15 then you will pay $7.5 (15 × $0.50 = $7.50) for the insurance. Then with probability p you will earn $22.5 ($30—$7.50) and with probability (1—p) you will earn $7.50 ($15 you covered minus $7.50 the cost of insurance). Note: you can buy any amount of insurance you want. In the example above you can buy up to 30 units of insurance. Also, you do not need to buy the full unit of your insurance you can buy parts of the unit. For instance, in this example, if you want to cover $23.32 you can buy 23.32 units of insurance which would cost you $11.66 (23.32 × $0.50).

Decision One

For this decision the probability (p) of loss is determined from your performance in the trivia questions you answered in Part II and will be equal to: the number of incorrect answers divided by 10. The more incorrect questions you answer the higher the probability that you will lose your earnings. For instance, if you answered 4 out 10 questions incorrectly then there will be a 40% chance that you will lose your earnings, but if you answered 8 out of 10 questions incorrectly there will only be an 80% chance that you lose your earnings.

Decision Two

For this decision you will be told what the probability (p) of loss and the price per unit of insurance and will be asked to make a decision on how much of your earnings you want to cover.

Decision Three

For this decision you will be told what the probability (p) of loss and the price per unit of insurance and will be asked to make a decision on how much of your earnings you want to cover.

Part V

In this part you will answer some demographic questions.

Questions and Survey

14.1 Trivia Questions

-

1.

Subsets of 10 trivia questions were pulled from the trivia questions below.

-

2.

On what continent is France located

-

3.

What geographical area was once referred to as ``Seward's Folly?''

-

4.

Where in the human body is food digested?

-

5.

What is the real name of the artist who once went by the pseudonyms ``Puffy'', ``Puff Daddy'', and ``P. Diddy''?

-

6.

Who is considered ``The King'' of rock?

-

7.

What sport does Oscar De LaHoya participate in?

-

8.

The pop star known for such songs as Like a Virgin, Material Girl, and Like a Prayer, goes by what single name (rather than a first and last name)?

-

9.

What city's NFL team is known as the Vikings?

-

10.

Who was the first African American to win an Academy Award for best actress?

-

11.

The study of the structural and functional changes in cells, tissues and organs that underlie disease is called what?

-

12.

J.K. Rowling's books tell about a young wizard named Harry who goes to a school called Hogwarts. What is Harry's last name?

-

13.

What state do the Yankees play for?

-

14.

Baghdad is the capital of what middle-eastern country?

-

15.

Who wrote and directed Kill Bill Volumes 1 and 2?

-

16.

What band was Justin Timberlake in?

-

17.

Laudanum is a form of what drug?

CRT Questions

-

1.

A bat and a ball cost $1.10 in total. The bat costs a dollar more than the ball. How much does the ball cost (in cents)?

-

2.

It takes 5 machines 5 min to make 5 widgets. How many minutes would it take 100 machines to make 100 widgets (enter a numeric value)?

-

3.

In a lake, there is a patch of lily pads. Every day, the patch doubles in size. If it takes 48 days for the patch to cover the entire lake, how many days would it take for the patch to cover half of the lake (enter a numeric value)?

-

4.

If John can drink one barrel of water in 6 days, and Mary can drink one barrel of water in 12 days, how long would it take them to drink one barrel of water together?

-

5.

Jerry received both the 15th highest and the 15th lowest mark in the class. How many students are in the class?

-

6.

A man buys a pig for $60, sells it for $70, buys it back for $80, and sells it finally for $90. How much has he made?

-

7.

Simon decided to invest $8,000 in the stock market 1 day early in 2008. Six months after he invested, on July 17, the stocks he had purchased were down 50%. Fortunately for Simon, from July 17 to October 17, the stocks he had purchased went up 75%. At this point, Simon has:

-

a.

broken even in the stock market

-

b.

is ahead of where he began

-

c.

has lost money

-

a.

Optimism Bias Questions

-

1.

In uncertain times, I usually expect the best.

-

a.

Strongly disagree

-

b.

Disagree

-

a.

Neither agree nor disagree

-

b.

Agree

-

c.

Strongly Agree

-

2.

If something can go wrong for me, it will.

-

3.

I'm always optimistic about my future.

-

4.

I hardly ever expect things to go my way.

-

5.

I rarely count on good things happening to me.

-

6.

Overall, I expect more good things to happen to me than bad.

Probability Questions

-

1.

Suppose you flip a fair coin, meaning that the probability of heads is 0.5 and the probability of tails is 0.5. Suppose you flip the coin twice. If the first time that you flip the coin it comes up heads, what is the probability that it will be heads on the second flip?

-

2.

Suppose that the probability that Ken shows up to work in a green shirt on any given day is 0.3 and that the probability that Jill shows up to work in a green shirt on any given day is 0.4. Assuming that Ken and Jill do not coordinate the shirts that they wear to work on any given day, what is the probability of both Ken and Jill showing up to work in green shirts on the same day?

-

3.

Suppose that the probability that a pregnant pig gives birth to one pig is 0.2 and the probability that she gives birth to two pigs is 0.8. The expected number of pigs that the pregnant pig will give birth to is?

-

4.

Suppose that the probability of rain tomorrow is 0.3. On days when it rains, the probability of 1 inch of rainfall is 0.5, the probability of 2 inches of rainfall is 0.3, and the probability of 3 inches of rainfall is 0.2. The expected amount of rainfall tomorrow is?

Risk Question

How do you see yourself? Are you a person who is generally willing to take risks, or do you try to avoid taking risks? Please indicate your answer on a scale from 0 to 10, where a 0 means "not at all willing to take risks," and a 10 means "very willing to take risks." You can use the values in between to indicate where you fall on the scale.

Survey

Gender

(a) Male

(b) Female

Age

How much trading experience do you have?

(a) None

(b) Some

(c) Average

(d) More than average

(e) Professional

How many Math and Statistics classes have you taken?

Education Level

(a) High School or GED

(b) Some College

(c) Undergraduate Degree

(d) Master's Degree

(e) Ph.D. Degree

Graphs and Tables

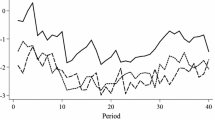

Poisson Distribution

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bregu, K. The effect of overconfidence on insurance demand. Geneva Risk Insur Rev 47, 298–326 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1057/s10713-021-00064-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s10713-021-00064-5