Abstract

Although theoretical models consistently predict that government spending shocks should lead to appreciation of the domestic currency, empirical studies have regularly found depreciation. Using daily data on U.S. defense spending (announced and actual payments), the paper documents that the dollar immediately and strongly appreciates after announcements about future government spending. In contrast, actual payments lead to no discernible effect on the exchange rate. It examines the responses of other variables at the daily frequency and explores how the response of the exchange rate to fiscal shocks varies over the business cycle as well as at the zero lower bound and in normal times.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Own-account investment is measured in current dollars by compensation of general government employees and related expenditures for goods and services and is classified as investment in structures, software, and research and development.

The threshold for contracts announced on the DoD website varied over time. For the most part of our sample, the threshold was 5 million dollars.

In contrast to vector autoregressions, the error term in specification (1) and other similar specifications is potentially serially correlated for h>1 and therefore one has to use Newey-West or similar estimators to calculate standard errors correctly.

In Auerbach and Gorodnichenko (2012a, 2012b and 2013), we use professional forecasts to further purify government spending series of predictable movements. Such forecasts unfortunately are not available at a daily frequency. We use 20 lags in all specifications; that is, I=J=20.

For details, see the discussion in O’Rourke and Schwartz (2014).

See General Accounting Office, Office of the General Counsel (2004, pp. 2-52).

The index includes the following corporations: Boeing Co, General Dynamics, Honeywell Intl Inc, L-3 Communications Holdings, Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman Corp, Precision Castparts Corp, Raytheon Co, Rockwell Collins, Textron Inc, United Technologies Corp, AAR Corp, Aerovironment Inc, American Science & Engineering, Cubic Corp, Curtiss-Wright Corp, Engility Inc., GenCorp Inc, Moog Inc A, National Presto Industries, Orbital Sciences Corp, Taser International Inc, and Teledyne Technologies Inc. These corporations are included in the S&P 1500 index. We use equal weights to aggregate movements of stock prices across corporations.

DoD announcements are made at 1700 hrs Eastern Time. Some markets are closed by this time and therefore some daily variables may be unable to respond to the announcement on the day it was made. In light of this discrepancy in timing, we use responses at h=1 in specifications (1)–(3) as a measure of the contemporaneous response.

The standard deviation of daily log changes in the exchange rate is 0.44 basis points. The response is similar when it is estimated using the standard VAR approach; see Figure A10.

According to the September 30, 2013 Daily Report of the U.S. Treasury, the total payment to defense contractors in the fiscal year of 2013 was 343 billion, which is equal approximately to 2 percent of the U.S. GDP. Note that this accounts for roughly half of the overall defense budget, which also includes labor expenses for soldiers and other employees, maintenance of military bases, military operations, and so on.

Ilzetzki, Mendoza, and Vegh (2013) do find that the exchange rate appreciates on impact for countries (developed and developing) with flexible exchange rates. However, this appreciation is temporary and the exchange rate depreciates shortly after the shock.

However, even with the better timing of military spending announcements constructed in Ramey (2011), we find only a moderate improvement in the reaction of the exchange rate. Specifically, instead of depreciation, the dollar exhibits no reaction to the Ramey spending shocks. See Figure A9.

The TED spread is calculated as the difference between the 3-month London Interbank Offer Rate (LIBOR) based on U.S. dollars and the 3-month Treasury bill rate.

We measure uncertainty using the Chicago Board Options Exchange (CBOE) DJIA Volatility Index. This index shows the hypothetical performance of a portfolio that engages in a buy-write strategy on the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA).

In contrast, payment shocks appear to lead to declines in foreign stock market indices (see Figure A2).

In contrast, the picture is mixed for responses to payment shocks (last four panels of Figure A2). Inflation expectations tend to decrease and nominal rates for U.S. government debt tend to fall while the nominal rates in the interbank market tend to rise. It is hard to reconcile these responses in a standard framework.

We continue to find no significant response to payment shocks.

Interestingly, the response to payment shocks (daily statements of the U.S. Treasury) shows the opposite cyclical variation: the response is larger in recessions than in expansions, although generally not significant statistically (Figure A3).

See Vitale (2007) for a survey.

In contrast, the dollar depreciates to a payment shock (not statistically significant). See Figure A6.

References

Andersen, Torben, Tim Bollerslev, Francis Diebold, and Clara Vega, 2003, “Micro Effects of Macro Announcements: Real-Time Price Discovery in Foreign Exchange,” American Economic Review, Vol. 93, No. 1, pp. 38–62.

Auerbach, Alan J. and Yuriy Gorodnichenko, 2012a, “Fiscal Multipliers in Recession and Expansion,” in Fiscal Policy after the Financial Crisis, ed. by A. Alesina and F. Giavazzi (Chicago: National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.), pp. 63–98.

Auerbach, Alan J. and Yuriy Gorodnichenko, 2012b, “Measuring the Output Responses to Fiscal Policy,” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, Vol. 4, No. 2, pp. 1–27.

Auerbach, Alan J. and Yuriy Gorodnichenko, 2013, “Output Spillovers from Fiscal Policy,” American Economic Review, Vol. 103, No. 3, pp. 141–46.

Benetrix, Agustin. S. and Philip R. Lane, 2013, “Fiscal Shocks and the Real Exchange Rate,” International Journal of Central Banking, Vol. 9, No. 3, pp. 6–37.

Blanchard, Olivier and Roberto Perotti, 2002, “An Empirical Characterization of the Dynamic Effects of Changes in Government Spending and Taxes on Output,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 117, No. 4, pp. 1329–68.

Born, Benjamin, Falko Juessen, and Gernot J. Müller, 2013, “Exchange Rate Regimes and Fiscal Multipliers,” Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, Vol. 37, No. 2, pp. 446–65.

Chodorow-Reich, Gabriel, 2014, “Effects of Unconventional Monetary Policy on Financial Institutions,” forthcoming in Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Vol. 48, No. 1, pp. 155–227.

Corsetti, Giancarlo, André Meier, and Gernot J. Müller, 2009, “Fiscal Stimulus with Spending Reversals,” IMF Working Papers 09/106 (International Monetary Fund).

De Livera, Alysha M., Rob J. Hyndman, and Ralph D. Snyder, 2011, “Forecasting Time Series with Complex Seasonal Patterns Using Exponential Smoothing,” Journal of the American Statistical Association, Vol. 106, Vol. 496, pp. 1513–27.

Enders, Zeno, Gernot J. Müller, and Almuth Scholl, 2011, “How Do Fiscal and Technology Shocks Affect Real Exchange Rates? New Evidence for the United States,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 83, No. 1, pp. 53–69.

Erceg, Christopher, Christopher Gust, and David López-Salido, 2007, “The Transmission of Domestic Shocks in Open Economies,” in International Dimensions of Monetary Policy, ed. by J. Galí and Mark J. Gertler (Chicago: National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.), pp. 89–148.

Fisher, Jonas D.M. and Ryan Peters, 2010, “Using Stock Returns to Identify Government Spending Shocks,” Economic Journal, Vol. 120, No. 544, pp. 414–36.

General Accounting Office, Office of the General Counsel. 2004, Principles of Federal Appropriations Law, Vol. 1. (Washington DC: General Accounting Office, Office of the General Counsel,), 3rd ed.

Gorodnichenko, Yuriy and Michael Weber, 2013, “Are Sticky Prices Costly? Evidence From The Stock Market,” NBER Working Paper No. 18860.

Ilzetzki, Ethan, Enrique G. Mendoza, and Carlos A. Vegh, 2013, “How Big (Small?) are Fiscal Multipliers?,” Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 60, No. 2, pp. 239–54.

Jorda, Oscar, 2005, “Estimation and Inference of Impulse Responses by Local Projections,” American Economic Review, Vol. 95, No. 1, pp. 161–82.

Kim, Soyoung and Nouriel Roubini, 2008, “Twin Deficit or Twin Divergence? Fiscal Policy, Current Account, and Real Exchange Rate in the U.S,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 74, No. 2, pp. 362–83.

Lyons, Richard, 2006, The Microstructure Approach to Exchange Rates(Cambridge, MA: MIT Press).

Meese, Richard and Kenneth Rogoff, 1983, “Empirical Exchange Rate Models of the Seventies: Do They Fit Out of the Sample?” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 13, No. 1–2, pp. 3–24.

Monacelli, Tommaso and Roberto Perotti, 2010, “Fiscal Policy, the Real Exchange Rate and Traded Goods,” Economic Journal, Vol. 120, No. 544, pp. 437–61.

O’Rourke, Ronald and Moshe Schwartz, 2014, Multiyear Procurement (MYP) and Block Buy Contracting in Defense Acquisition: Background and Issues for Congress. Congressional Research Service Report R41909, July 30.

Parker, Jonathan A., Nicholas S. Souleles, David S. Johnson, and Robert McClelland, 2013, “Consumer Spending and the Economic Stimulus Payments of 2008,” American Economic Review, Vol. 103, No. 6, pp. 2530–53.

Ramey, Valerie and Matthew D. Shapiro, 1998, “Costly Capital Reallocation and the Effects of Government Spending,” Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy Vol. 48, No. 1, pp. 145–194.

Ramey, Valerie, 2011, “Identifying Government Spending Shocks: It’s All in the Timing,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 126, No. 1, pp. 1–50.

Ravn, Morten O., Stephanie Schmitt-Grohé, and Martín Uribe, 2012, “Consumption, Government Spending, and the Real Exchange Rate,” Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 59, No. 3, pp. 215–34.

Schwartz, Moshe and Wendy Ginsberg, 2013, Department of Defense Trends in Overseas Contract Obligations. Congressional Research Service Report R41820, March 1.

Vitale, Paolo, 2007, “A Guided Tour of The Market Microstructure Approach to Exchange Rate Determination,” Journal of Economic Surveys, Vol. 21, No. 5, pp. 903–34.

Wieland, Johannes, 2012, “Fiscal Multipliers at the Zero Lower Bound: International Theory and Evidence,” UCSD manuscript.

Woodford, Michael, 2011, “Simple Analytics of the Government Expenditure Multiplier,” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 1–35.

Additional information

*Alan Auerbach is the Robert D. Burch Professor of Economics and Law and directs the Burch Center for Tax Policy and Public Finance at the University of California, Berkeley. Yuriy Gorodnichenko is an Associate Professor in the University of California, Berkeley, Department of Economics and a Research Associate in the NBER. The authors are grateful to Seunghwan Lim, Walker Ray, and Mauricio Ulate for excellent research assistance. They thank Olivier Coibion, Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas, Johannes Wieland and participants in the Jacques Polak Annual Research Conference and at the University of Oregon for comments, and Andrew Austin and David Newman for guidance regarding the defense appropriations process. Gorodnichenko thanks the NSF for financial support. Auerbach thanks the Burch Center for Tax Policy and Public Finance for financial support.

An erratum to this article is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1057/s41308-017-0034-4.

Electronic supplementary material

Appendix

Appendix

See Figures A1, A2, A3, A4, A5, A6, A7, A8, A9 and A10 and Table A1.

Time Series for Additional Macroeconomic Variables. Panel A: Trade Weighted U.S. Dollar Index: Major Currencies; Panel B. TED Spread

Notes: Panel A: Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, H.10 Foreign Exchange Rates. Panel B: TED spread is calculated as the spread between 3-month LIBOR based on U.S. dollars and 3-month Treasury bill.

Responses of Additional Macroeconomic Variables to a Government Spending Shock, U.S. Treasury Daily Payments

Notes: Impulse responses to a unit shock in the U.S. Treasury payments on defense contracts are estimated using specification (1). All series are taken from FRED© database. FRED codes are reported in parentheses: TED spread (TEDRATE), CBOE DJIA Volatility Index (VXDCLS), S&P500 Stock Price Index (SP500). The horizon (horizontal axis) is measured in days. NIKKEI, FTSE 100, and TSX are stock market indices for exchanges in Tokyo (Japan), London (the U.K.), and Toronto (Canada).

Responses of Interest Rates and Inflation Expectations to a Government Spending Shock, U.S. Treasury Daily Payments

Notes: Impulse responses to a unit shock in the U.S. Treasury payments on defense contracts are estimated using specification (1) with h=1. All series are taken from FRED© database. FRED codes are reported in parentheses: Treasury (DGS*), LIBOR (USD*D156N), LIBOR (GBP*D156N), Inflation Swap (DSWP*), where * denotes the maturity. LIBOR (GBP) reports the response for the interest rates set in the British pound.

Rolling Regressions, 24-Month Window, U.S. Treasury Daily Payments

Notes: Contemporaneous responses to a unit shock in the U.S. Treasury payments on defense contracts are estimated using specification (1). The government spending series is the daily U.S. Treasury payments to defense contractors. Vertical lines identify recessions as identified by the NBER. The horizontal axis shows calendar time.

Controls for Macroeconomic News. Panel A: Control for monetary policy shocks; Panel B: Control for macroeconomic surprises; Panel C. Control for monetary policy shocks and macroeconomic surprises

Notes: Impulse responses to a unit shock in a government spending series are estimated using specification (1) augmented with controls indicated in the panel title and described in the section “Robustness.” The horizon (horizontal axis) is measured in days. Responses (vertical axis) are in basis points.

State-Dependent Responses to a Government Spending Shock, Business Cycle, U.S. Treasury Daily Payments to Defense Contractors. Panel A: Expansion vs. Recession; Panel B: Expansion vs. Recession by ZLB regime; Panel C. Expansion vs. Recession by ZLB regime, control for the TED rate

Notes: Impulse responses to a unit shock in the U.S. Treasury payments on defense contracts are estimated using specification (2). The horizon (horizontal axis) is measured in days. The government spending series is the daily U.S. Treasury payment to defense contractors.

State-Dependent Responses of the Exchange Rate to a Government Spending Shock, Business Cycle and ZLB. Department of Defense Announcements. Panel A: Baseline; Panel B. Control for TED rate

Notes: Impulse responses to a unit shock in the DoD announcement government spending series are estimated using specification (3). The horizon (horizontal axis) is measured in days.

Response of the Exchange Rate to Macroeconomic News and Monetary Policy Shocks. Panel A. Exchange rate response to innovations in monetary policy: Quantitative easing (Chodorow-Reich, 2014); Panel B: Exchange rate response to innovations in monetary policy: Innovations to fed fund rate target (Gorodnichenko and Weber, 2013); Panel C: Exchange rate response to news about unemployment rate (constructed as in Andersen and others, 2003)

Notes: Panels A and B show that when interest rates increase in response to a change in monetary policy, the U.S. dollar appreciates. Panel C shows that when the released figures for the U.S. unemployment rate is greater than anticipated, the U.S. dollar depreciates. The horizon (horizontal axis) is measured in days.

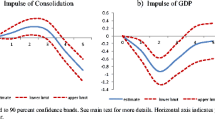

Response of the Exchange Rate to a Government Spending Shock (quarterly data)

Notes: Blanchard-Perotti identification amounts to putting government spending first in the Cholesky ordering. Ramey identification is based on the narrative approach applied to military spending. Ramey shocks are measured in percent of GDP. Impulse responses in both panels are calculated using local projections. The list of controls includes four lags of growth rate of real GDP, inflation rate (GDP deflator), government spending (corresponding series), and the exchange rate (see note to Figure 4). The horizon (horizontal axis) is measured in quarters. Responses are to a unit shock in government spending.