Abstract

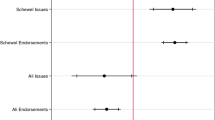

Political scientists have long tried to explain how interest group lobbying and political action committee campaign donations affect election outcomes and public policy debates. Unfortunately, they are often met with null or conflicting results. Consequently, scholars have tested the influence of campaign donations on Congressional outcomes in different parts of the policy-making process, such as roll call votes and committee hearings. Building on these findings, I use the adoption of a Marcellus Shale impact fee in Pennsylvania to test whether campaign contributions have a different effect on bill amendment roll call votes than final floor votes. Given the differing political contexts of these two votes, it stands to reason that there is variation in the relationship between campaign donations and member voting behavior. Specifically, I expect that legislators have more flexibility in voting on amendments than on final bills, and thus factors other than party, including campaign funding, are also relevant. I find that while party, ideology and tenure are the only significant factors associated with roll call votes on final bills, campaign contributions and local-level salience are positively associated with voting on amendments. This shows that while moneyed interests may not be successful in stopping undesirable legislation, they can achieve legislative victory by shaping the bill as it travels through the legislature.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

These estimates remain in flux and will become more precise as drilling continues. See also the 2011 Marcellus Shale Advisory Committee Report to Pennsylvania Governor Tom Corbett for gas yield estimates being used by Pennsylvania state officials.

The tax would have taken 5 per cent at the wellhead, in addition to 4.7 cents per thousand cubic feet of production (Snow, 2009).

In comparison, Texas’s effective rate is 5.4 per cent.

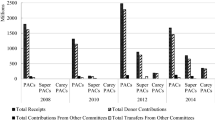

Donations totaled more than $23 million from 2000 through early 2012, for all state-elected officials. Data from Marcellus Money (http://marcellusmoney.org/) include donations to legislative, gubernatorial and judicial candidates in Pennsylvania.

Granted, this may mean who those that voted against the final bill fall into one of two groups – (1) those who opposed the legislation because it was not enough and (2) those who are strongly opposed to any taxation of the industry. However, the design of the analysis implicitly controls for this. The primary concern would be Republicans who voted against the fee (that is, the second group). In fact, the parties voted in almost solid blocks on HB 1950 and SB 1100, with Republicans voting for the fee and Democrats voting against. Ultimately, there were only 11 Republican members of the House and six Republican members of the Senate who voted against the impact fee in one of its two forms (that is, HB 1950 or SB 1100). Of the Senators, only three voted against the final bill reported from the conference committee. While mixing group 2’s votes with those of Democrats and Republicans that were truly opposed to the fee (that is, group 1) may add a small amount of statistical noise to the models, I do not expect it to detract from the final conclusions.

The data were collected from quarterly donation filings made by candidates with the Pennsylvania Department of State.

There is an important potential limitation in this variable, as it only measures pro-industry donations. As noted above, there are also anti-industry (for instance, pro-environment) PACs in Pennsylvania. If these groups donate to campaigns, it would be important to include their counter-influence in the model. However the National Institute of Money in State Politics’ database of state campaign contributions contains very few pro-environmental donations for 2008–2010. This suggests that pro-environmental groups use methods other than campaign contributions to influence state legislators. Therefore, their limited amount of donation activity is not included in the model.

Though the estimation of ideal points for state legislators is developing (Shor et al, 2010) and such data do exist for 1996–2009 (Shor and McCarty, 2011). Unfortunately, these estimates are not available for the period of this study.

The ACU began scoring states in 2011 for Florida, Nevada, North Carolina, Ohio and Virginia. They subsequently expanded the scoring to 15 states in 2012 and plan to expand to all 50 states within the next 5 years.

State Representatives Orie (R-40) and Wagner (D-22) did not serve out their terms and were thus not scored by the ACU. Consequently, their votes are not included in the final analysis. Also, voting on HB 1950 was included in the scoring of Pennsylvania Senators. This was removed from the calculation of their ideology score.

Drawn from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (http://www.bls.gov/ro3/palaus.htm).

Drawn from estimates by StateImpact. Again, because legislators’ districts tend to span more than one county, this variable measures the sum of the revenue share across the applicable counties. A sum was used instead of an average because the pressure to adopt would likely be additive from each of the counties.

The most recent election was in 2010 for all members of the Pennsylvania House of Representatives. Because only half of the Senate is replaced each election cycle, Senators in odd districts were elected in 2010, but those in even districts were elected in 2008. Additionally, Senators Argall (R-29), Brewster (D-45), and Schwank (D-11) each came to office through special elections in 2009, 2010 and 2011, respectively. The vote data were drawn from the Pennsylvania Department of State election returns database (http://www.electionreturns.state.pa.us).

Tenure is measured as the total number of years a member has served in the Pennsylvania state legislature.

Note that the scale on the odds ratio plots for the Republican and Senate covariates are different than for the remainder of the covariates. Hence, they are plotted separately for clarity of interpretation. The differential scaling results from the dichotomous nature of the two variables.

Note that the probabilities for Democrats are truncated. This is due to the fact that the top Democrat recipient of donations in the 2008–2010 election cycle (Senator Timothy Solobay) received $32 250, while the top grossing Republican (Senator Joseph Scarnati) received $165 000. Thus, there is no support in the data for predicted probabilities above $32 250 for Democrats.

References

American Conservative Union (ACU). (2012) 2012 State Legislative Ratings Guide. American Conservative Union.

Austen-Smith, D. and Wright, J.R. (1994) Counteractive lobbying. American Journal of Political Science 38 (1): 25–44.

Baumgartner, F.R. and Leech, B.L. (1998) Basic Interests: The Importance of Groups in Politics and in Political Science. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Baumgartner, F.R. and Jones, B.D. (2005) Agendas and Instability in American Politics, 2nd edn. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Berry, W.D., Ringquist, E.J., Fording, R.C. and Hanson, R.L. (1998) Measuring citizen and government ideology in the American states, 1960–93. American Journal of Political Science 42 (1): 327–348.

Berry, W.D., Fording, R.C., Ringquist, E.J., Hanson, R.L. and Klarner, C.E. (2010) Measuring citizen and government ideology in the American states: A re-appraisal. State Politics & Policy Quarterly 10 (2): 117–135.

Bosso, C.J. (1987) Pesticides and Politics: The Life Cycle of a Public Issue. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Carter, D. (1964) Power in Washington. New York: Random House.

Cigler, A.J. (1991) Interest groups: A subfield in search of an identity. In: W. Crotty (ed.) Political Science: Looking to the Future, Vol. 4. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

Constant, L.M. (2006) When money matters: Campaign contributions, roll call votes, and school choice in Florida. State Politics & Policy Quarterly 6 (2): 195–219.

Dow, J.K. and Endersby, J.W. (1994) Campaign contributions and legislative voting in the California Assembly. American Politics Research 22 (3): 334–353.

Dusso, A. (2012) Legislation, political context, and interest group behavior. Political Research Quarterly 63 (1): 55–67.

Evans, D.M. (1986) PAC contributions and roll-call voting: Conditional power. In: A.J. Cigler and B.A. Loomis (eds.) Interest Group Politics, 2nd edn. Washington DC: Congressional Quarterly.

Francis, W.L. (1985) Leadership, party caucuses, and committees in US state legislatures. Legislative Studies Quarterly 10 (2): 243–257.

Fritschler, A.L. (1975) Smoking and Politics, 2nd edn. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Givel, M.S. and Glantz, S.A. (2001) Tobacco lobby political influence on US state legislatures in the 1990s. Tobacco Control 10 (2): 124–134.

Glantz, S.A. and Begay, M.E. (1994) Tobacco industry campaign contributions are affecting tobacco control policymaking in California. Journal of the American Medical Association 272 (15): 1176–1182.

Gordon, S.B. (2001) All votes are not created equal: Campaign contributions and critical votes. The Journal of Politics 63 (1): 249–269.

Gray, V. and Lowery, D. (1996) The Population Ecology of Interest Representation: Lobbying Communities in the American States. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Green, J.C. and Bigelow, N.S. (2005) The Christian Right goes to Washington: Social movement resources and the legislative process. In: P.S. Hernson, R.G. Shaiko and C. Wilcox (eds.) The Interest Group Connection. Washington DC: Congressional Quarterly.

Grenzke, J.M. (1989) PACs and the congressional supermarket: The currency is complex. American Journal of Political Science 33 (1): 1–24.

Hall, R.L. and Wayman, F.W. (1990) Buying time: Moneyed interests and the mobilization of bias in congressional committees. The American Political Science Review 84 (3): 797–820.

Hansen, J.M. (1991) Gaining Access: Congress and the Farm Lobby, 1919–1981. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Heinz, J.P., Laumann, E.O., Nelson, R.L. and Salisbury, R.H. (1993) The Hollow Core: Private Interests in National Policymaking. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Hojnacki, M., Kimball, D.C., Baumgartner, F.R., Berry, J.M. and Leech, B.L. (2012) Studying organizational advocacy and influence: Reexamining interest group research. Annual Review of Political Science 15: 379–399.

Hojnacki, M. and Kimball, D. (1998) Organized interests and the decision of whom to lobby in Congress. The American Political Science Review 92 (4): 775–790.

Hojnacki, M. and Kimball, D. (1999) The who and how of organizations’ lobbying strategies in committee. The Journal of Politics 61 (4): 999–1024.

Hojnacki, M. and Kimball, D. (2001) PAC contributions and lobbying access in congressional committees. Political Research Quarterly 54 (1): 161–180.

Laumann, E.O. and Knoke, D. (1987) The Organizational State: Social Choice in National Policy Domains. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press.

Linehan, P. (2010) Saving Penn’s woods: Deforestation and reforestation in Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania Legacies 10 (1): 20–25.

Lowery, D. (2013) Lobbying influence: Meaning, measurement and missing. Interest Groups & Advocacy 2 (1): 1–26.

Luke, D.A. and Krauss, M. (2004) Where there’s smoke there’s money: Tobacco industry campaign contributions and US congressional voting. American Journal of Preventative Medicine 27 (5): 363–372.

Marcellus Shale Advisory Commission of Pennsylvania. (2011) Governor’s Marcellus Shale Advisory Commission Report. Harrisburg, USA: Office of the Governor.

Shor, B., Berry, C. and McCarty, N. (2010) A bridge to somewhere: Mapping state and congressional ideology on a cross-institutional common space. Legislative Studies Quarterly 35 (3): 1–32.

Shor, B. and McCarty, N. (2011) The ideological mapping of American legislatures. American Political Science Review 105 (3): 530–551.

Smith, R.A. (1995) Interest group influence in the U.S. Congress. Legislative Studies Quarterly 20 (1): 89–139.

Snow, N. (2009) Pennsylvania eyes severance tax. Oil and Gas Journal 107 (8): 29.

United States Energy Information Administration (EIA). (2012) Annual Energy Outlook, http://www.eia.gov/forecasts/aeo/pdf/0383(2012).pdf, accessed 5 February 2014.

Walker, J.L. (1991) Mobilizing Interest Groups in America. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Witko, C. (2006) PACs, issue context, and congressional decisionmaking. Political Research Quarterly 59 (2): 283–295.

Wright, G.C. and Schaffner, B.F. (2002) The influence of party: Evidence from the state legislatures. American Political Science Review 96 (2): 367–379.

Wright, J. (2004) Campaign contributions and congressional voting on tobacco policy, 1980–2000. Business and Politics 6 (3): 1–26.

Yackee, J.W. and Yackee, S.W. (2006) A bias towards business? Assessing interest group influence on the US bureaucracy. The Journal of Politics 68 (1): 128–139.

Acknowledgements

Previous versions of this article were presented at the 2013 Pennsylvania Political Science Association Conference in Harrisburg, PA, and the Center for American Political Responsiveness at Penn State. I benefited greatly from the participants’ comments. I would also like to thank Charles Crabtree, Marie Hojnacki, David Lowery, Christopher Ojeda, Kevin Reuning, and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on this manuscript. Any mistakes or omissions are my own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mallinson, D. Upstream influence: The positive impact of PAC contributions on Marcellus Shale roll call votes in Pennsylvania. Int Groups Adv 3, 293–314 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1057/iga.2014.3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/iga.2014.3