Abstract

The authors use US data to explore the relationship between job satisfaction and sexual orientation. The results indicate that gay men and lesbians who are married experience lower job satisfaction compared with similar heterosexual men and women. The authors propose the following reasons for this finding: (1) married gay men and lesbians may be more visible as sexual minorities and therefore more susceptible to discrimination and harassment; (2) strong opposition to same-sex marriage may intensify that adverse treatment; and (3) the failure of employers to provide benefits for same-sex spouses may further reduce job satisfaction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Gates [2011] compiled figures on percentages of gays/lesbians and bisexuals from several studies. In US studies, the percentage of adults who identify as gay/lesbian ranged from 1.0 to 2.5; the percentage identifying as bisexual ranged from 0.7 to 3.1. The percentages tended to be lower in non-US studies than in US studies, and for most of the studies, gays/lesbians outnumbered bisexuals.

Some economic studies of sexual orientation in the United States use Census data. Others, including seminal work in the area by Badgett [1995], use the General Social Survey. The Census data have larger samples of sexual minorities, but provide no information on job satisfaction. Given our research interest, we have chosen to use the GSS data. By comparison, Badgett’s [1995] research relied upon a GSS sample with only 81 individuals who were identified as sexual minorities (47 males and 34 females). In their work with the GSS, Berg and Lien [2002] fared a little better, with 64 males and 52 females. Given the longevity of the GSS, we are able to base our results on samples that included larger numbers of sexual minorities (236 males and 201 females).

The percentage of GSS respondents being classified as sexual minorities increases between 1988 and 2010. The pattern is largely associated with significant upward trends in the percentages of lesbians and female bisexuals; there are no significant trends in the percentages of gays and male bisexuals.

Age-squared was omitted from the specification because of problems with violation of the second-order condition.

As part of our analysis, we also tested for the endogeneity of the log-of-hours-worked variable, using a procedure described in Smith and Blundell [1986].

A comparison of the results with and without the terms interacting sexual orientation with marital status revealed the following concerning job satisfaction. For men, in the specification without interaction terms, the effect of sexual orientation on the probability of being moderately satisfied vs dissatisfied was significantly negative for gay males; however, our specification with interaction terms reveals that effect to be present primarily among the married men. For women, no effects of sexual orientation were apparent in the specification without interaction terms; the negative effect for lesbians pertaining to the probability of being very satisfied vs moderately satisfied only became visible when we included the interaction terms (and then only for married women).

This explanation uses the theoretical framework introduced by Locke [1976], who stated that job satisfaction depends on both (1) the gap between one’s expectations or desires regarding a job and the actual aspects of the job, and (2) the importance that the individual places on those aspects.

To test whether our estimates for the job satisfaction equations were affected by the possibility of endogeneity of our log-of-hours-worked variable (lnhrs), the following procedure was applied (separately for men and women). First, an equation with lnhrs as the dependent variable was estimated (using OLS and allowing for the presence of sample selectivity associated with the decision to work). It was determined that there was sample selectivity for women but not for men. Next, we calculated the residuals from the equation with the Heckman correction for lnhrs for women and the residuals from the equation without the Heckman correction for lnhrs for men. The residuals were then entered as additional right-hand variables in the corresponding job satisfaction equations. Given that the coefficients of the residuals in the job satisfaction equations for both genders were found to be insignificant, we concluded that an endogeneity problem did not exist (in accordance with Smith and Blundell [1986]).

References

Andrisani, Paul J. 1978. Job Satisfaction among Working Women. Signs, 3 (3): 588–607.

Antecol, Heather, and Michael Steinberger . 2013. Labor Supply Differences between Married Heterosexual Women and Partnered Lesbians: A Semi-Parametric Decomposition Approach. Economic Inquiry, 51 (1): 783–805.

Badgett, M.V. Lee . 1995. The Wage Effects of Sexual Orientation Discrimination. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 48 (4): 726–739.

Badgett, M.V. Lee, Holning Lau, Brad Sears, and Deborah Ho . 2007. Bias in the Workplace: Consistent Evidence of Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Discrimination. Williams Institute, UCLA School of Law, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, http://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/Badgett-Sears-Lau-Ho-Bias-in-the-Workplace-Jun-2007.pdf (accessed May 24, 2012).

Bartel, Ann P. 1981. Race Differences in Job Satisfaction. Journal of Human Resources, 16 (2): 294–303.

Bender, Keith A., Susan M. Donohue, and John S. Heywood . 2005. Job Satisfaction and Gender Segregation. Oxford Economic Papers, 57 (3): 479–496.

Berg, Nathan, and Donald Lien . 2002. Measuring the Effect of Sexual Orientation on Income: Evidence of Discrimination? Contemporary Economic Policy, 20 (4): 394–414.

Carleton, Cheryl J., and Suzanne H. Clain . 2012. Women, Men, and Job Satisfaction. Eastern Economic Journal, 38 (3): 331–355.

Carpenter, Christopher S. 2008. Sexual Orientation, Income, and Non-Pecuniary Economic Outcomes: New Evidence from Young Lesbians in Australia. Review of Economics of the Household, 6 (4): 391–408.

Clark, Andrew E. 1997. Job Satisfaction and Gender: Why are Women so Happy at Work? Labour Economics, 4 (4): 341–372.

Clark, Andrew E. 2001. What Really Matters in a Job? Hedonic Measurement Using Quit Data. Labour Economics, 8 (2): 223–242.

Clark, Andrew E., and Andrew J. Oswald . 1996. Satisfaction and Comparison Income. Journal of Public Economics, 61 (3): 359–381.

Coombs, Robert H. 1991. Marital Status and Personal Well-Being: A Literature Review. Family Relations, 40 (1): 97–102.

Department of Justice, Canada 2012. Canadian Human Rights Act. Justice Laws Website, http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/h-6/page-1.html#h-2 (accessed January 12, 2014).

Donohue, Susan M., and John S. Heywood . 2004. Job Satisfaction and Gender: An Expanded Specification from the NLSY. International Journal of Manpower, 25 (2): 211–234.

Drydakis, Nick . 2012. Men’s Sexual Orientation and Job Satisfaction. International Journal of Manpower, 33 (8): 901–917.

Freeman, Richard B. 1978. Job Satisfaction as an Economic Variable. American Economic Review, 68 (2): 135–141.

Gates, Gary J. 2011. How Many People Are Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender? Williams Institute, UCLA School of Law, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, http://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/Gates-How-Many-People-LGBT-Apr-2011.pdf (accessed January 12, 2014).

Greene, William H., and David A. Hensher . 2008. Modeling Ordered Choices: A Primer and Recent Developments. Social Science Research Network, http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1213093 (accessed March 24, 2013).

Heckman, James . 1976. The Common Structure of Statistical Models of Truncation, Sample Selection and Limited Dependent Variables and a Simple Estimator for Such Models. Annals of Economic and Social Measurement, 5 (4): 475–492.

Lafrance, Emélie, Casey Warman, and Frances Woolley . 2009. Sexual Identity and the Marriage Premium. Department of Economics, Queens University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada, http://qed.econ.queensu.ca/working_papers/papers/qed_wp_1219.pdf (accessed April 7, 2013).

Laumann, Edward O., John H. Gagnon, Robert T. Michael, and Stuart Michaels . 1994. The Social Organization of Sexuality: Sexual Practices in the United States. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Leppel, Karen . 2009. Labour Force Status and Sexual Orientation. Economica, 76 (301): 197–207.

Leppel, Karen . 2014a. Does Job Satisfaction Vary with Sexual Orientation? Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society, 53 (2): 169–198.

Leppel, Karen . 2014b. The Method of Generalized Ordered Probit with Selectivity: Application to Marital Happiness. Journal of Family and Economic Issues. Forthcoming, advance online publication, 24 May 2014; doi: 10.1007/s10834-014-9407-2.

Locke, Edwin A. 1976. The Nature and Causes of Job Satisfaction. in Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology. edited by Marvin D. Dunnette. Chicago: Rand-McNally, 1319–1328.

Mehta, Cyrus R., and Nitin R. Patel . 1983. A Network Algorithm for Performing Fisher’s Exact Test in R × C Contingency Tables. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 78 (382): 427–434.

Scott, K. Dow, and G. Stephen Taylor . 1985. An Examination of Conflicting Findings on the Relationship between Job Satisfaction and Absenteeism: A Meta Analysis. Academy of Management Journal, 28 (3): 599–612.

Sloane, Peter J., and Hector Williams . 2000. Job Satisfaction, Comparison Earnings, and Gender. Labour, 14 (3): 473–502.

Smith, Richard J., and Richard W. Blundell . 1986. An Exogeneity Test for a Simultaneous Equation Tobit Model with an Application to Labor Supply. Econometrica, 54 (3): 679–685.

Smith, Tom W., Peter V. Marsden, Michael Hout, and Jibum Kim . 2011. General Social Surveys, 1972–2010. [machine-readable data file]. Principal Investigator, Tom W. Smith; Co-Principal Investigators, Peter V. Marsden and Michael Hout, NORC ed. Chicago: National Opinion Research Center, producer, 2005; Storrs, CT: The Roper Center for Public Opinion Research, University of Connecticut, distributor. 1 data file (55,087 logical records) and 1 codebook (3,610 pp).

Sousa-Poza, Alfonso, and Andres A. Sousa-Poza . 2000. Taking Another Look at the Gender/Job-Satisfaction Paradox. KYKLOS, 53 (2): 135–152.

Stratton, Leslie S. 2002. Examining the Wage Differential for Married and Cohabiting Men. Economic Inquiry, 40 (2): 199–212.

Tebaldi, Edinaldo, and Bruce Elmslie . 2006. Sexual Orientation and Labour Supply. Applied Economics, 38 (5): 549–562.

Williams, Richard . 2012. Generalized Ordered Logit Models for Ordinal Dependent Variables. Department of Sociology, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana, http://www3.nd.edu/~rwilliam/stata/gologit3.hlp (accessed July 29, 2013).

Zavodny, Madeline . 2008. Is There a “Marriage Premium” for Gay Men? Review of Economics of the Household, 6 (4): 369–389.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Appendices

Appendix A

Mathematical details of methodology

The latent job satisfaction variable (S*) is assumed to be a function of the independent variables (X): S*=Xβ 1 +ɛ, where β 1 is a vector of unknown parameters and ɛ is a stochastic disturbance term. In the situation in which the observed dependent variable (S) has three categories, and τ is another vector of unknown parameters, it is assumed that

Equivalently, and switching the second and third cases for ease of exposition:

An additional latent variable allows for sample selection bias associated with individuals’ decisions to work for pay. Individuals are working if the utility of working exceeds the utility of remaining unemployed or out of the labor force. The difference in the utilities (Y*) is unobservable, but assumed to be a function of personal characteristics (Z). That is, Y*=Zγ +u, where γ is a vector of unknown parameters and u is a stochastic disturbance term. An individual is a job holder (L=1), if Y*>0 or u>−Zγ. An individual is not a job holder (L=0), if Y*⩽0 or u⩽−Zγ.

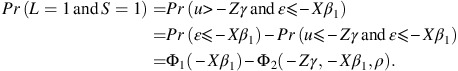

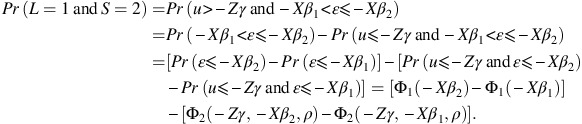

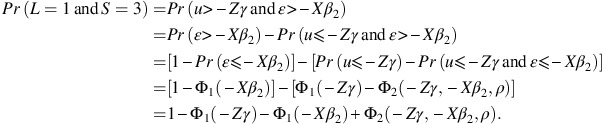

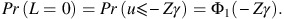

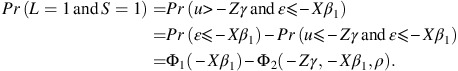

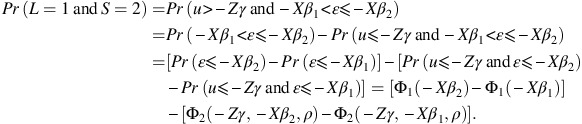

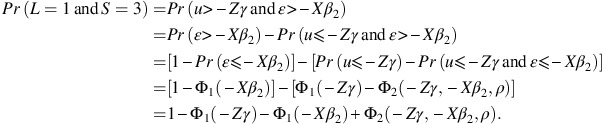

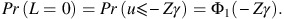

There are therefore four possible cases: (i) L=1 and S=1; (ii) L=1 and S=2; (iii) L=1 and S=3; and (iv) L=0. Let Ф1 denote a univariate cumulative normal distribution and Ф2 denote a bivariate cumulative normal distribution. Assume that u and ɛ are distributed as bivariate normal with means of 0, standard deviations of 1, and correlation ρ. The probabilities of the four cases are then calculated as below.

-

Case 1:

-

Case 2:

-

Case 3:

-

Case 4:

The probabilities were used to construct a weighted log likelihood function, where sampling weights were provided by the data source. This function was then estimated using a maximum likelihood technique and the SAS NLMIXED procedure.

Note that in Case 2, it is assumed that −Xβ 1 is less than −Xβ 2 . If this assumption does not hold, then the probability of Case 2 could be negative. The problem of negative probabilities has been recognized as a potential concern in generalized ordered choice models. However, according to Williams [2012], “[t]his seems to be a fairly rare occurrence, and … may not be worth worrying about” if there are just a few cases. In our estimation results, there were no such cases.

Appendix B

Descriptive statistics and estimation results for working vs not working

The descriptive statistics for the characteristics of the full sample of working and non-working respondents are shown in Table B1. The estimation results for the work status equation are reported in Table B2.

For men, our estimation results suggest that there is no significant impact of sexual orientation on the probability of working. This finding is somewhat consistent with those reported by Tebaldi and Elmslie [2006], in their study of homosexual and heterosexual couples. These authors find that under certain circumstances, there is no significant difference in the probability of not working for gay and heterosexual men, all other things being the same. However, Tebaldi and Elmslie do find that gay men with dependents or a recent period of joblessness have a higher probability of not working, compared with heterosexual counterparts.

For women, our results suggest that lesbians are significantly more likely to be working, compared with heterosexual counterparts. Tebaldi and Elmslie [2006] report somewhat similar findings, with lesbians significantly more likely to be at work, compared with heterosexual counterparts, when there are no dependents in the household. They find that the presence of dependents narrows this difference, however.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Leppel, K., Clain, S. Exploring Job Satisfaction by Sexual Orientation, Gender, and Marital Status. Eastern Econ J 41, 547–570 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1057/eej.2014.38

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/eej.2014.38