Abstract

Consultants working on commercial projects often fail to take account of the deep and broad academic literature on the topic on which they are working. Because of his position as a hybrid academic and consultant, the author is obliged to keep closely in touch with the different literatures for the areas in which he teaches – broadly marketing, customer relationship management, customer service and branding. As the number of management journals increases, so the supply of research-based articles increases, and it becomes harder for practitioners to stay in touch with it. The author has therefore identified that a critical role in his research projects for clients is to review the academic and other literatures for clients. This particular literature review was part of a white paper project commissioned by a hi-tech client to help them understand how the management of problems affects the management of customer relationships. It excludes a section on social media, which was too client specific and therefore confidential to be published. Social media will be the subject of a later paper.

Similar content being viewed by others

BACKGROUND

Although the Internet has made information on progress in management much more widely available, it is not necessarily accessible to practitioners. Consultants working on commercial projects often fail to take account of the deep and broad academic literature on the topic on which they are working. In some cases this is because they may not have the time (or budget) to work on it, in other cases it may be because the journal articles are phrased rather arcanely (from a busy consultant's point of view). Because of his position as a hybrid academic and consultant, the author is obliged to keep closely in touch with the different literatures for the areas in which he teaches – broadly marketing, customer relationship management (CRM), customer service and branding.

As the number of academic management journals increases, so the supply of research-based articles increases, and it becomes harder for practitioners to stay in touch with it. The author has therefore identified that a critical role in his research projects for clients is to review the academic literature for clients.

This particular literature review was part of a white paper project commissioned by a hi-tech client to help them understand how the management of problems affects the management of customer relationships. It excludes a section on social media, which was too client specific and therefore confidential to be published. Social media will be the subject of a later paper.

WHAT THE ACADEMICS SAY

A selection from the hundreds of articles that have appeared in the last few years on service recovery, service satisfaction and complaints management have been reviewed. Much of the literature is based upon research into firms in service industries, not product manufacturers. The product itself provides a service, and there is a large literature on how the focus on the service delivered by a product changes marketing and service management – the service-dominant logic literature.1

Below are the main conclusions that appear to be useful. Each article cited is underpinned by a substantial literature review and in nearly all cases by an empirical study. Each summary therefore includes conclusions from the literature reviewed by the authors (who are cited in the end-note for each section) as well as from their own research. Each heading covers one article.

Service excellence and delight

Service excellence is about being ‘easy to do business with’, but it is both obtrusive and elusive. Customers know when they have received it and when they have not. Such service, both excellent and poor, has a strong emotional impact upon individuals as customers, creating intense feelings about the organisation, its staff and its services, and influencing their loyalty to it. Yet many organisations find service excellence elusive and hard to grasp and deliver. As individuals, however, people know what it is and how simple it can be.

It is often assumed that delight is the result of (excellent) service that exceeds expectations, but this definition has its drawbacks, as exceeding expectations may be unnecessarily costly. It creates over-quality, which cannot be justified for economic reasons. Customers may see over-quality as exceeding what is needed, which can even create bad word-of-mouth. Over-quality may give the impression that a product or service is overpriced, even if this is not so. It may also raise customers’ expectations, so what might have been regarded as excellent becomes simply adequate or expected, unless the company continues investing in this spiral of increasing quality and expectations so as to keep exceeding expectations. In fact, service excellence is just about being ‘easy to do business with’ (not necessarily exceeding expectations). Excellent service is described simply as ‘a pleasure’. There are no hassles or difficulties.

Poor service organisations are a ‘pain to do business with’. They are often described as ‘a nightmare’ to deal with. Their staff and systems made it difficult for customers to do business with them. They just do not care about the customers or their experiences. Customers understand when they buy a low price or no-frills product or service and happily accept the company's business proposition. Some such companies make it into the list of companies providing excellent service. Customers do not forgive no, or poor, service appropriate to the proposition.

Excellent service is described in these ways:

-

delivering the promise;

-

providing a personal touch;

-

going the extra mile;

-

dealing well with problems and queries.

The characteristics of poor service are the opposite:

-

not delivering what was promised;

-

being impersonal;

-

not making any effort;

-

not dealing well with problems and queries.

Nearly half of the statements describing excellent service were about problem handling and 64 per cent of the statements of poor service were about problem and complaint handling. Problem handling is a key driver of people's perceptions of excellent or poor service.

The question of fairness

What customers think of service recovery depends on their expectations and whether they think they were treated fairly during the process. The psychological effect of the initial service failure does not affect how they feel about the recovery process. A successful service recovery is a positive surprise and creates strong positive feelings (delight). One that is perceived to be unsuccessful by the complainer will create strong negative feelings (anger).

Low-expecting complainers will see mainly positive, better-than-expected outcomes, while high-expecting complainers will see only negative results. The complainer has expectations of both the recovery process and the outcome.

The fact that equity has a stronger impact on satisfaction with service recovery than disconfirmation indicates that the perception of justice is more important to the complainer than the recovery process. In other words, the perception of injustice will remain despite a positive disconfirmation of expectations of service recovery. Therefore, complaint handling should focus on the outcome primarily and secondly on the process. The perception of fairness in the outcome of the complaint is more important than the disconfirmation of expectations of service recovery.

Fairness may not imply that the customer is always right. Information given to customers on the cause of the incident may alter complaining customers’ attribution of cause and effect. Dissatisfied complaining customers expect a good explanation of what has happened, an apology, empathy with their situation and an effort to make them happy again. In short, they expect the company to take responsibility for the situation and solve it. A speedy recovery when things go wrong is important.

The front-line must be empowered to do what they perceive as right or fair for the situation and customer in question. Front-line behaviour when receiving the complaint is important in providing good service recovery. When speedy recovery is not possible, due for example to complex legal matters, the company must give customers updated information during the process.

Management must upgrade the status of the service recovery function within the company and ensure that the best staff become members of the recovery team. They must classify and analyse what goes wrong, when and why. Customer dissatisfaction data must be fed back to policy makers, whose performance partly depends on these data. Companies must be willing to give customers the benefit of the doubt. The starting point must be that customers are honest and claims legitimate. Starting by thinking that the customer is dishonest will distance the company from the customer.2

Fairness, loyalty, trust and voice

Distributional fairness and procedural fairness during service recovery greatly improve scores for service quality, customer satisfaction, customer loyalty and trust, whereas interactional fairness only enhances customer trust perceptions. Established customers have higher expectations of recovery effort than new customers. Customers are likely to complain about additional service attributes once they decide to complain about a certain attribute. Service recovery efforts are of short-term importance, while reliability is needed to build long-term relationships. Most customers facing perceived inequity will try to restore equity with post-purchase behaviour, including complaining, word-of-mouth communication, brand loyalty and repurchase intention, as well as loss of trust.

Dimensions of fairness include procedural and the interactional fairness perceptions. Procedural fairness represents the fairness of the process that leads to a certain outcome. Customers want to participate in and influence the distributional decision - they want to have a ‘voice’. How the customer is treated in terms of respect, politeness and dignity is captured by interactional fairness, although an apology does not seem to be important for overall customer satisfaction. Therefore, procedural fairness could be spoilt by a rude, impersonal interactional style of obtaining information and communicating outcomes.

An apology could be viewed as an example of interactional fairness. Both fairness dimensions enhance perceptions of fairness and satisfaction when there is a favourable outcome (distributional fairness), but when there is a negative outcome, the two dimensions have a weaker effect and can decrease fairness and satisfaction perceptions.

There is a distinction between benevolent, equity sensitive and entitled customers. Benevolent customers are sensitive to under-reward or negative inequity, equity-sensitive customers to equity and entitled customers to over-reward or positive inequity. The recovery effort should reflect customer recovery expectations.

If the profitability of recovery efforts is to be maximised, companies should recover from service failures without wasting resources. Recovery effort should depend on the magnitude of failure (does the customer feel annoyed or victimised?), the tangibility of the product (good or service), organisational commitment (new or established customer), customer's equity sensitivity (benevolent, equity sensitive or entitled), potential negative or positive word-of-mouth and the expenditures necessary to recover. However, tailoring of recovery efforts might reduce perceived fairness, especially when recovery efforts are very visible to other customers. If customers receive tailored recoveries, some might feel deprived if other people receive a more advantageous treatment following a similar complaint – today this would be revealed in social media.

Customers who have a satisfactory relationship with a company will not leave after just one failure, but only after several failures. Successful recovery that directly increases encounter satisfaction increases overall satisfaction as well.

The effects of a single failure will be different for existing or new customers. New customers may not have previous good experiences with the company, so a failure will be more serious. Existing customers with a good relationship with the company will be more tolerant of a service failure. However, established customers have more stringent recovery expectations due to stronger commitment to the company. So, a service recovery that fails to restore feelings of equity for existing customers may still have serious effects on the long-term relationship.

Compensation and a listening ear are important in recovery from service failure and to nurture long-term relationships. Service personnel should have the autonomy to help customers in real time, including the authority to offer compensation without management interference. Managers should investigate fairness for their specific industry, since fairness appears to have different meanings in different sectors. Whereas in some, distributional fairness is most important, in others procedural or even interactional fairness are more important.3

How loyalty works in recovery

Loyal customers are likely to put greater emphasis on procedural fairness than non-loyal customers as it is more personal and reflects respect for the relationship. More loyal customers may overlook a single outcome or forgive what they see as an aberrant failure as long as the relational aspects support fairness over time. Key relational concerns include: (1) standing or status, which refers specifically to politeness and respect for dignity, (2) the neutrality of the decision and (3) trust in those third parties to treat people fairly and reasonably.

Customers with lower levels of loyalty are less interested in the fairness of procedures and interpersonal treatment that form the basis for a longer-term relationship, particularly after experiencing a service failure early in the exchange. Those less loyal are more likely to be concerned with a fair economic and tangible transaction (for example, refund, credit, exchange) and less concerned about the relational, social elements. In contrast to procedural fairness, a fair outcome is the ‘typical metric’ for judging fairness transactions in economic exchange relationships.

Customer pre-failure loyalty has a positive effect on subsequent perceptions of the problem being solved satisfactorily. Prior positive experiences mitigate the negative impact of poor complaint handling on subsequent levels of customer commitment. Successful experiences tend to counterbalance a failure.

However, customer loyalty may be a liability, as loyal customers are more likely to value the relationship and perceive it as social, with the expectation of being treated fairly in interactions with the company and receiving better or preferential treatment in exchange for their loyalty, to maintain equity in the relationship. When they think they have been treated unfairly, they may react more negatively than those with less invested prior to the service failure. So, the most damage will occur when expectations for service recovery are high but recovery is poor. While well-managed failures may have the most positive influence on loyal customers, the poorly managed failures experienced by loyal customers will lead to the most significant detriment in reactions.

Customers are more likely to perceive outcomes such as monetary funds, credits, and so on, as fair if they are treated fairly and respectfully in interactions with managers and employees, but when procedural justice is low, outcomes are likely to be seen as unfair. Most loyal customers react most negatively when treated unfairly. So, policies that empower employees during service recovery should allow employees to employ the full range of remedies for loyal customers. Loyal customers should be treated with great respect and managers should take time to explain decisions leading to the outcomes of service recovery.4

The service recovery paradox – A risky business

Although excellent recoveries can enhance customer satisfaction and increase repatronage, viewing service failures as opportunities to impress customers with good service performance may involve substantial risks. Customers need to have as many as 12 positive experiences with a company to overcome the negative effects of one bad experience. The service recovery paradox is where customers whose service failures are satisfactorily remedied seem more satisfied, more likely to remain loyal and more likely to engage in favourable word-of-mouth about the company than customers who had not experienced a failure.

However, nearly half of dissatisfactory service encounters were due to employees’ inability or unwillingness to respond to service failures. It is not the initial failure that caused the dissatisfactory encounter but the employee's response to the failure that caused the incident to be recalled unfavourably by the customer. So, it was not the service failure itself, but the failure to recover that caused the customer to be dissatisfied.

This has been referred to as a ‘double deviation’ from customer expectations of service organisations. These negative evaluations by customers prompt behavioural responses that translate directly into losses for service firms. Service failures and failed recoveries account for over half of the critical behaviours by companies that lead directly to customer switching. Of these, nearly half were cited as the sole reason for the customer switching to another company.

Customers revise and update their satisfaction judgments and repatronage intentions based on prior assessments and new information. Service encounters involving a failure and recovery provide the customer with new information so that he/she can update his/her satisfaction and repatronage intentions.

Transaction-specific satisfaction is a post-choice evaluative judgment of a specific purchase and consumption experience. A customer might form a transaction-specific assessment of his/her satisfaction with an organisation's recovery from a service failure. In contrast, cumulative satisfaction reflects the customer's feelings about multiple experiences, encounters or transactions with the service organisation. Customers who attribute outcomes to stable and permanent causes are more confident that the same outcome will recur than customers who attribute outcomes to unstable causes. Consequently, a customer's inference about whether the cause of the service failure is stable or unstable over time influences his/her repatronage intentions.

After controlling for the effects of prior cumulative satisfaction and repatronage intentions, customers have higher levels of cumulative satisfaction and repatronage intentions when they are more satisfied with the organisation's recovery from a service failure. Customers’ memories of prior service experiences, as reflected in their prior cumulative satisfaction and repatronage intentions, significantly affect their revised cumulative satisfaction and repatronage intentions.

The effect of the customer's prior experiences is small compared with his/her satisfaction with the recovery from the service failure. Cumulative satisfaction and repatronage intentions decrease after failure and recovery, for most customers.

Cumulative satisfaction and repatronage intentions increase when customers are very satisfied with the handling of a failure. Customers do not forget, but are willing to forgive and rebuy. The impact of dis/satisfaction with service recovery is larger for outcome failures than process failures. It is (unsurprisingly) harder to recover from major failures. A highly satisfactory recovery will maintain or increase cumulative satisfaction and loyalty, but a dissatisfactory recovery will decrease cumulative satisfaction and loyalty. In other words, every customer must be satisfied with the organisation's recovery after every service failure - or the organisation risks alienating and losing customers.

Even the best service organisations will find it hard to provide highly effective recoveries for every service failure. More than half of all efforts to respond to customer complaints actually reinforce negative reactions to a service. Therefore, most organisations will find it necessary to invest substantially in customer service to make highly satisfactory recoveries an achievable goal.

Customers seem to formulate their repatronage intentions under a ‘what have you done for me lately’ heuristic. If their most recent experience is not favourable, they are likely to substantially revise their repatronage intentions. Furthermore, if a customer does repatronise after a dissatisfactory failure/recovery episode, a second negative service experience is likely to completely eliminate any goodwill because customers’ repatronage intentions have little memory.

These observations suggest that differentiation through superior customer service (rather than price) and relationship building is critical for service organisations. Although excellent service recoveries can lead to increased customer satisfaction and repatronage intentions, this is only at the very highest levels of customers’ recovery ratings. Organisations may be better served by doing it right the first time.5

Service recovery paradox is rare

The literature exploring the service recovery paradox produces mixed results. The paradox is rare, making its measurement difficult, as the ‘treatment group’ sample size is usually too small to produce significant results. Hypothesised differences are significant but small, which diminishes their managerial relevance. While failure offers an opportunity to create an excellent recovery, the likelihood of a service paradox is very low. Ineffective service followed by an outstanding service recovery is not a viable strategy. The rarity of the paradox limits its managerial relevance.6

Complaint management and knowledge

Few firms excel at handling service failures. Employees cannot improve service processes when they experience recovery and companies still do not learn from service failure. Recovery ineffectiveness is due to the competing interests of managing employees, customers and processes. To address these criticisms, complaint management must find new approaches to achieving consistency and to aligning the interests between a company's actions and the needs of its customers and employees. Service recovery performance depends upon an organisation's commitment to incorporate knowledge management into complaint management processes and upon its ability to manage knowledge assets in each complaint management step.7

Complaint management and employees

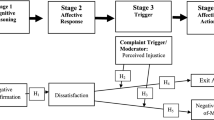

An organisation's service recovery procedures lead to three distinct outcomes: customer, process and employee recoveries.

Many organisations have focused their efforts on customer recovery and have, to some extent, ignored the potentially higher impact outcomes of process and employee recovery. Service recovery procedures have more impact on employees and process improvement than on customers. Many organisations seem concerned with service recovery but few are good at it or get the benefits of recovered customers, improved processes or recovered employees.

By focusing recovery procedures on satisfying or delighting customers, organisations miss substantial benefits. Many organisations have some way to go to develop their recovery procedures.8

Recovery voice

Research studies into failures and recovery have conceptualised ‘voice’ in terms of customers being able to air complaints after failures occur. Recovery voice entails a company asking a customer (after a failure has occurred) what it can do to rectify the problem. Customers perceive greater procedural justice when offered recovery voice, and this leads to higher overall post-failure satisfaction. Perceived procedural justice mediated the effect of recovery voice on overall satisfaction. Recovery voice has a greater impact on perceived procedural justice for established customers with long transaction histories than for new ones with short transaction histories.9

Measuring recovery satisfaction

RECOVSAT can be used to assess customer satisfaction with recovery efforts. Companies can use their customer complaint database to calculate satisfaction with service recovery scores (RECOVSAT scores) for different geographical regions, for different business units or different departments, even per individual employee. These scores can be linked to remuneration or service level agreements. The RECOVSAT instrument measures satisfaction with six dimensions of service recovery - communication, empowerment, feedback, atonement, explanation and tangibles, as follows:

-

Communication – how far employees communicate clearly, ask questions to clarify the situation, are understanding, reliable and honest in trying to solve the problem.

-

Empowerment - whether the employee who first received the complaint can solve the problem, without the help of someone else.

-

Feedback - whether the company gives written feedback about progress in solving the problem, and also whether they offer a written apology.

-

Atonement - whether the company apologises for any financial loss, ensures the customer is not ‘out of pocket’ and does so politely.

-

Explanation – whether the company explains what went wrong and how satisfactorily.

-

Tangibles – whether the employees with whom the customer deals are well-dressed and work in a tidy, professional, environment.10

Recovery and gender

Male and female consumers put different emphases on elements of the recovery process. When companies, irrespective of gender, display concern and give customers voice opportunity and a sizable compensation, both men and women reported more positive attitudes compared with when this was not so. Combinations of high voice opportunity with high outcome and high voice opportunity with high concern strongly influenced perceptions of effort, regardless of gender. However, women want their views heard during recovery attempts and to provide input. Men view voice as less important.11

Recovery and organisational learning

Management of service failure catalyses organisation-wide learning. Failure-recovery is an external-to-internal trigger that initiates various changes – operational, strategic and conceptual - that guide implementation of value-enhancing innovations. Service recovery is not just a ‘damage-control’ mechanism affecting the ‘shop floor’ level, but part of a company's strategic planning to ensure that its offerings are continuously improved. Recovery that leads to value enhancement takes the firm through three stages of service orientation:

-

Operational – undertake immediate recovery of the failure or offer alternative options so that customers’ needs are met; compensate customers for the service mishap and acknowledge their understanding; provide immediate rewards for employees involved in successful recovery; and provide further training to employees who may have contributed to the initial failure.

-

Strategic – align the company's external orientation with internal orientation; undertake a systematic analysis and management of the entire service delivery system; use the identified service problem and its remedy to realign the inner mechanisms of the service system; nurture the culture of organisation-wide learning through assimilation and dissemination of information; learn from failure and recovery information; and effect improvement that will reflect on the firm's competency and market performance.

-

Vision – aligning the company's mission and direction, initiate innovative value enhancement that systematically progresses through the company's operations, strategy and vision for the ultimate benefit of customers, employees and the company itself.12

Complaints management and profit

Many organisations ignore the operational value of complaints, so many complaint processes are geared to mollifying customers rather than ensuring that problems do not recur. There are relationships between financial performance and complaint processes, satisfaction, retention, process improvement, employee attitude and retention.

Several factors have been identified to suggest what is meant by a ‘good’ complaint management. These include:

-

having clear procedures;

-

providing a speedy response;

-

the reliability (consistency) of response;

-

having a single point of contact for complainants;

-

ease of access to the complaints process;

-

ease of use of the process;

-

keeping the complainant informed;

-

staff understand the complaint processes;

-

complaints are taken seriously;

-

employees are empowered to deal with the situation;

-

having follow-up procedures to check with customers after resolution;

-

using the data to engineer-out the problems;

-

using measures based on cause reduction rather than complaint volume reduction.

The main purpose of robust and effective complaint management systems is to increase profits by increasing revenues and reducing costs. However, it is not complaint processes per se that produce financial benefit but how intervening variables are managed, that is improving financial performance by satisfying and retaining customers or employees, improving product or improving processes. The complaint process may be good but if it does not lead to retention (staff or customer) or improvement it may have limited financial impact. To generate maximum financial benefit from complaints, organisations should design complaint management processes to focus on process improvement and employees, rather than customer satisfaction per se. There are four acid tests for companies to use to see if they are getting the most from their complaint processes:

-

Do they satisfy customers who have experienced a failure?

-

Do they retain those customers who have experienced a failure?

-

Do they improve organisation-wide processes as a result of information from failures?

-

Do they help retain employees?

Financial benefits accrue from satisfying and retaining dissatisfied customers through service, but few organisations have high scores in terms of satisfaction, retention, improvement and financial performance.13

Estimating complaints management profitability (CMP)

A comprehensive empirical study was conducted among complaint managers of major German companies in the business-to-consumer market. It showed that the CMP knowledge deficit is even higher than expected. Usually, customer care and complaint management departments are considered as operational units that only have to handle customer dialogue but are not involved in strategic planning processes. They are seen mainly as a cost factor and not a potential profit source. This leads – especially in tough times – to pressure to reduce costs. Complaint managers can only escape this by proving the contribution of complaint management to value creation. This is a huge challenge. It is not clear what the costs and benefits of complaint management are and how benefits can be monetised.

The costs of complaint management include:

-

personnel costs from human resources directly concerned with complaint management processes (for example, staff of a complaint management department);

-

administration costs, for example office space and office equipment;

-

communication costs, for example phone costs or postage;

-

response costs, for example costs from voluntary (planned or discretionary) compensation (for example, gifts or vouchers); repair costs.

The benefits of complaint management include:

-

The information benefit - the value of using information from complaints to improve products, to enhance efficiency and to reduce failure costs.

-

The attitude benefit - the positive attitude changes of customers due to achieved satisfaction.

-

The repurchase benefit - when a complaining customer stays with a company instead of switching.

-

Communication benefits - the positive word-of-mouth.

To calculate CMP it is necessary to operationalise the four types of benefits and to value them monetarily. The sum of the benefits less the measured costs equals the profit of complaint management. To calculate the return on complaint management (ROCM), which is the key indicator for complaint management profitability, the profit of complaint management is set against the complaint management investments (costs).

A comprehensive cost calculation requires all complaint-handling processes to be defined clearly. Detailed activity-based costing must be implemented for a systematic association of cost rates with handling processes. In practice, not all complaint reception and handling processes are defined in detail and monitored continuously by a complaint management system. In particular, processing of and reaction to rare problem types, which need the help of other departments or which demand complex internal investigations, are often defined incompletely. In addition, not all companies use activity-based costing. So, not all types of costs are recorded regularly. The purpose of internal cost calculation is not only to measure the ROCM, but also to serve internal cost control. The recurrence of certain problems can be reduced by charging the responsible department with the costs of complaint handling. However, the necessary data are not always available while a particular problem cannot always be assigned to one department.

Knowledge is better for costs than for benefits. One reason for this is the absence of consensus on benefit types and their monetary valuation. However, the essential objectives of complaint management are to prevent dissatisfied customers from exiting the relationship and to use the information that is contained in customer complaints within the company. If complaint managers want to control whether these objectives are met, they have to estimate the repurchase and information benefit of complaint management. Some companies have information on the retention effects of their complaint management activities from customer surveys or customer data analysis. Equally, figures based on experience of the usage of complaint information for innovation and failure reduction can be expected. So while complaint managers do not know the profitability of their complaint management exactly, they can give a rough profitability estimation. If the benefit cannot be calculated monetarily, the value of information is assessed in terms of importance and degree of improvement using a scoring model. The economic assessment is then performed by assigning an estimated monetary value to each scoring point.

The attitude effect comes from the improvement of attitude values of complainants. The customer attitude after the resolution of a complaint case is compared to the attitude after the original occurrence of the problem. The difference represents the quantification of the attitude effect. A direct monetary assessment of this type of benefit is not possible, but can be estimated by analysing the costs of the attempt to reach a corresponding improvement of attitude by means of marketing strategies (for example, advertising).

Complainants engage in positive word-of-mouth communication about their complaint experiences and thereby recommend the company and its products/services to other customers. For the economic calculation of this effect, two types of data are necessary: the number of people who are addressed by customers who are delighted or very satisfied by the company's reaction to their complaints, and an influence rate. The latter is the share of addressed people who actually became buyers as a result of the positive depiction or buying recommendation. These data can be obtained by market research. The absolute number of customer relationships initiated by word-of-mouth can be multiplied by the average customer profit on a yearly basis or under consideration of the average duration of customer.

The repurchase benefit of complaint management is achieved when previously dissatisfied customers, who otherwise would have migrated, remain loyal to the company as a result of complaint management activities. There are different approaches to calculating this. For example, a calculation on the basis of individual customer data concerning customer value is possible, or, if these data are not available, on the basis of the corresponding average.14

CONCLUSIONS

This literature review provides some useful insights into consumers’ attitudes towards and behaviour during the complaints and recovery process. However, they should be applied only along with sector-specific contextual insight. Here are the main conclusions from the review:

Below for reference is a summary of the main practical conclusions that I reached from the above review and also from my knowledge of the more popular managerial literature, which I also reviewed for the client.

-

Complaints are a critical element of the voice of the consumer. It is much better for a complaint to be voiced than for the consumer to spread it to many other consumers (much facilitated by the web, particularly by social media) and to exit or leave. Complaints and associated issues of product and service reliability are also focused on by regulators and consumer advocates (for example, complaint websites, consumer surveys), and so are seen by companies as needing to be managed properly.

-

How well a complaint is managed is a key determinant of consumer satisfaction, which maybe correlated with loyalty. The successful resolution of complaints is almost as important as ensuring that the reason for the complaint does not recur.

-

Complaints are a key part of consumer contact management. They should be solicited rather than unsolicited, easy to make, quickly responded to, with both the problem of the consumer and the cause ‘fixed’.

-

Complaints may not be immediately identifiable as such – they may take other forms, such as requests for more information, questions for clarification or requests for variations in products, terms, and so on.

-

Having an issue which warrants a complaint is often the trigger for the consumer to voice their perceptions and feelings for the first time and they may or may not voice things to the supplier (and in the intermediated case, may voice them to a retailer, agent or other intermediary).

-

Being able to voice (and being able to do so easily) acts as a release of pressure and may create a sense of equity.

-

A very annoyed consumer will seek ways to voice their opinion. Today it takes them seconds on the web to find out how to voice to the world. However, the ease of complaining to the world versus complaining to the supplier is rising.

-

Consumers may want to voice opinions at any time, via any channel, in their journey, before, during or after failure/problems, at times of critical incidents or moments of truth.

-

If the complaint is managed poorly, this leads to the double exposure of complaint both about the original issue and about the quality of the recovery process. Second-order complaints relate to complaints about the resolution process.

-

Ease of access to the Internet is an important differentiator between consumers who find complaining easy or difficult. Innovative consumers may experience more problems due to technical teething problems, but are more likely to be able to (and to want to) sort it out themselves via the web.

-

Consumers’ fundamental requirement is for suppliers to be easy to deal with, for there to be no or few surprises in getting service from the product, and when there are unpleasant surprises, for the issues to be resolved quickly and painlessly.

-

The reliability problem that consumers face is recovery to a fully available product functioning as it should – the value recovery cycle. If repeated failure occurs, the consumer journey starts to change, and the consumer becomes more concerned with exit without financial penalty.

-

Equity and fairness in the recovery process may be as important to consumers as the outcome of recovery. Consumers who see themselves as being loyal have greater equity expectations, underlining the importance of those handling a complaint or recovery process having access to data which informs them of the consumers’ likely previous history (for example, are they really loyal, as they claim, or are they complaining just to get a better deal?).

-

Even if recovery is very good, it is dangerous to rely on the recovery paradox, where consumers with problems become more loyal than consumers who have never experienced failure because of the recovery process quality. The effect of the initial failure may outweigh that of the recovery, in all but situations where the consumer has experienced excellent recovery. However the probability of the recovery being so excellent as to outweigh the effects of the initial service or product failure is low.

-

Some suppliers track the effect of quality of service recovery on consumer satisfaction and loyalty, generally through market research tracking studies. The lower the incidence of complaints, the less likely they are to be picked up by tracking studies, though the tracking study is more likely to cover other aspects of the consumer's experience and history, particularly if the consumer leaves.

-

Research into consumers who complain is hard to execute, and should in theory wait until after recovery, otherwise it would be contaminated by the recovery process still being under way. The research could itself contaminate the recovery process (for example, the consumer would feel that the research gave them additional voice).

-

Complaints management is part of the overall CRM approach for suppliers who manage consumers individually, particularly for those that use CRM strategies, techniques, processes and systems. For these companies, knowledge about a complaint and its resolution state should be available during the CRM process. The complaints management angle is often integrated into a wider project focusing on the consumer journey (particularly for products and services involving complex consumer experiences over a period) and consumer experience management.

-

Knowledge (supplier and consumer view) from the complaints management process should be used to improve the design of consumer management processes and systems, as well as products and service. It is a key element of management review of the supplier's success in managing its consumers, products and services.

-

Companies learn how to improve their complaints management by internal benchmarking and harnessing the knowledge of those involved in the complaints management process, but also by external benchmarking, often through associations of consumer service managers or through user groups of companies using particular dedicated complaints management systems.

-

Products and services are increasingly being designed to avoid consumers needing to complain and where possible, to allow consumers to fix problems themselves.

-

Keeping consumers informed during the complaint management process is seen as very important.

-

Analysis, segmentation and testing of new resolution routines are now central to efficient complaints management. Hotspots for complaining are particularly important, for example for new consumers, for new products, for consumers’ first purchase/use of a new product, end of product life. The Pareto rule applies, so it is important to understand and manage it. Real-time analysis is becoming more important as product life cycles shorten. This enables early reliability problems to be identified and fed back to product development for rectification, while self-service diagnosis and solutions are developed.

-

The complaints management system is very important. It may be a ‘best of breed’ consumer feedback system (now including full social media feedback) or a module of a broader CRM system. In either case, integration of complaints management within the main CRM process and system and incorporation of the outputs of social media are important. There is the usual debate about whether optimisation of system choice is as important as making the best use of whatever system is acquired or developed.

-

For companies that (mostly or entirely) sell their products through intermediaries, attention should be focused on ensuring that where possible the product can be self-diagnosed and self-fixed (usually using web diagnostics in the case of electronic equipment such as laptops and smart phones).

-

Where the above is not possible, second-stage resolution may rely on the intermediary, though increasingly intermediaries want to minimise their work in this area and prefer immediate escalation to the manufacturer, with a like-for-like product switch funded by the manufacturer, as is the norm in many other areas of retailing. The failed item is then either remanufactured or scrapped.

-

Substitution of a low value alternative is often used, where the situation makes this inappropriate (for example, it is just too expensive, the product is already obsolescent or obsolete, or where fraud is suspected), but this is rarely satisfactory. This confirms the experience of car hire during the automotive insurance repair cycle, where substitution of low value small cars causes high levels of dissatisfaction and subsequent attrition, which have been partly mitigated by building in to the insurance premium a charge which covers like-for-like replacement.

-

For lower cost products, the guarantee registration process is used as a way of controlling for fraud, though consumers’ rights have advanced so much that most consumers do not bother with this process.

-

At a minimum, a replacement policy should be agreed with the intermediary, published and monitored for compliance and fraud (including that of retailer staff).

-

In industries where the technology advances very quickly, and where new components and software are constantly being incorporated, the ‘steady-state’ reliability that is needed to compile accurate statistics about failures and to manage failures tightly based upon expected failure rates does not exist. In these circumstances, where a product is seen to perform unsatisfactorily, it may take time to identify whether the problem lies in the product itself (and if so which component), the software, the information that the software is trying to access. However, the advantage of such products is the ability to build in self-diagnosis, using either the device itself or connection to the web via a computer. Still, if anticipated failure and care policy are not built in to the design of the product and the processes by which it is launched and marketed, problems are likely to be more severe.

-

Improved complaint management produces a good return on investment. This is via improvements in consumer retention, market share and positive word of mouth - turning negative into positive experiences and improved branding, consumer loyalty, improved design of the service experience and improved product design.

-

Most suppliers do not quantify the benefits. Commitment to improved complaints management is largely an act of faith.

-

Additional revenue and profit can be generated from the recovery process, not just by the normal business case methods of improved retention and recommendation, but by up/cross-sell. However, it must be managed sensitively and normally after full recovery has been achieved.

References

Vargo, S.L. and Lusch, R.F. (2008) Service-dominant logic: Continuing the evolution. Journal of the Academy Of Marketing Science 36 (1): 1–10.

Andreassen, T.W. (2000) Antecedents to satisfaction with service recovery. European Journal of Marketing 34 (1/2): 156–175.

de Ruyter, K. and Wetzels, M. (2000) Customer equity considerations in service recovery: A cross-industry perspective. International Journal of Service Industry Management 11 (1): 91–108.

Miller, M. and Robbins, T. (2004) Considering customer loyalty in developing service recovery strategies. Journal of Business Strategies 21 (2): 95–109.

Smith, A.K. and Bolton, R.N. (1998) An experimental investigation of service failure and recovery encounters: Paradox or peril? Journal of Service Research 1 (1): 65–81.

Michel, S. and Meter, M.L. (2008) The service recovery paradox: True but overrated? International Journal of Service Industry Management 19 (4): 441–457.

Abdelfattah, T. and Samiha, M. (2008) Toward E-Knowledge Based Complaint Management. Tunis: University of Tunis.

Johnston, R. and Michel, S. (2008) Three outcomes of service recovery: Customer recovery, process recovery and employee recovery. International Journal of Operations & Production Management 28 (1): 79–99.

Karande, K., Magnini, V.P. and Tam, L. (2007) Recovery voice and satisfaction after service failure: An experimental investigation of mediating and moderating factors. Journal of Service Research 10 (2): 187–203.

Boshoff, C. (2005) A re-assessment and refinement of RECOVSAT – An instrument to measure satisfaction with transaction-specific service recovery. Managing Service Quality 15 (5): 410–425.

McColl-Kennedy, J.R., Daus, C.S. and Sparks, B.A. (2003) The role of gender in reactions to service failure and recovery. Journal of Service Research 6 (1): 66–82.

La, K.V. and Kandampully, J. (2004) Market oriented learning and customer value enhancement through service recovery management. Managing Service Quality 14 (5): 390–401.

Johnston, R. (2001) Linking complaint management to profit. International Journal of Service Industry Management 12 (1): 60–69.

Stauss, B. and Schoeler, A. (2004) Complaint management profitability: What do complaint managers know? Managing Service Quality 14 (2/3): 147–156.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stone, M. Literature review on complaints management. J Database Mark Cust Strategy Manag 18, 108–122 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1057/dbm.2011.16

Received:

Revised:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/dbm.2011.16